Fritz Lenz

Fritz Gottlieb Karl Lenz (9 March 1887 in Pflugrade, Pomerania – 6 July 1976 in Göttingen, Lower Saxony) was a German geneticist, member of the Nazi Party,[1] and influential specialist in eugenics in Nazi Germany.

Biography

The pupil of Alfred Ploetz, Lenz took over the publication of the magazine "Archives for Racial and Social Biology" from 1913 to 1933 and received in 1923 the first chair in eugenics in Munich. In 1933 he came to Berlin where he established the first specific department devoted to eugenics, at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics.

Lenz specialised in the field of the transmission of hereditary human diseases and "racial health". The results of his research were published in 1921 and 1932 in collaboration with Erwin Baur and Eugen Fischer in two volumes that were later combined under the title Human Heredity Theory and Racial Hygiene (1936).

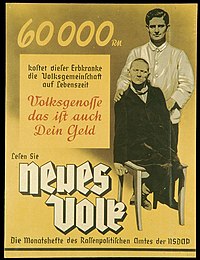

This work and his theory of "race as a value principle" placed Lenz and his two colleagues in the position of Germany's leading racial theorists. Their ideas provided scientific justification for Nazi ideology, in particular its emphasis on the superiority of the "Nordic race" and the desirability of eliminating allegedly inferior strains of humanity – or "life unworthy of life" (Lebensunwertes Leben). Lenz was a member of the "Committee of Experts for Population and Racial Policy". He joined the Nazi party in 1937 while serving as the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics.[1]

After World War II, Lenz continued to work as a Professor of genetics at the University of Goettingen. When questioned, Lenz said that the Holocaust would undermine the study of human genetics and racial theory. He continued to believe that eugenic theories of racial differences had been scientifically proven.[citation needed]

Two of his sons are Hanfried Lenz and Widukind Lenz.

Theories

For Lenz, human genetics established that the connection between racial identity and human nature was actually physical in character. This extended to political affiliations. Lenz even claimed that the revolutionary agitation in Germany after 1918 was caused by inferior racial elements, warning that the nation's racial superiority was threatened. He stated that "The German nation is the last refuge of the Nordic race … before us lies the greatest task of world history".[2] For Lenz, this validated the racialised politics of the Nazis.

He justified the Nuremberg laws of 1935 in this way:

- As important as the external features for their evaluation is the lineage of individuals, a blond Jew is also a Jew. Yes, there are Jews who have most of the external features of the Nordic race, but who nevertheless display Jewish mental tendencies. The legislation of the National Socialist state therefore properly defines a Jew not by external race characteristics, but by descent.[3]

Likewise, Lenz took the view that Slavs were inferior to Nordic peoples, and that they threatened to "overrun the superior Volk (people)." In 1940, Lenz advised the SS that "The resettlement of the Eastern zone is … the most consequential task of racial policy. It will determine the racial character of the population living there for centuries to come."[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b "Human biodiversity: genes, race, and history", Jonathan M. Marks. Transaction Publishers, 1995. p. 88. ISBN 0-202-02033-9, ISBN 978-0-202-02033-4.

- ^ Geoffrey G. Field, "Nordic Racism", Journal of the History of Ideas, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1977, p. 526

- ^ Fritz Lenz, Über Wege und Irrwege rassenkundlicher Untersuchungen, in: Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie Bd. 39, 3/1941, S. 397