Henry Rollins

Henry Rollins | |

|---|---|

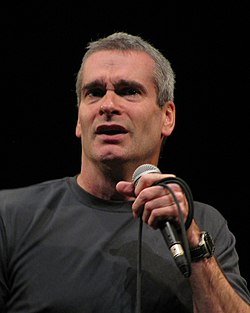

Rollins performing at the Bronson Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, March 23, 2010 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Henry Lawrence Garfield |

| Born | February 13, 1961 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Genres | Hardcore punk, alternative metal, spoken word |

| Occupation(s) | Performer, writer, journalist, publisher, actor, radio host, activist, musician |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals |

| Years active | 1980–present |

| Labels | 2.13.61, SST |

| Website | www |

Henry Rollins (born February 13, 1961) is an American musician, writer, journalist, publisher, actor, radio host, spoken word artist, and activist.[1][2][3] He is now hosting a radio show and doing speaking tours.[4][5]

After performing for the short-lived Washington D.C.-based band State of Alert in 1980, Rollins fronted the California hardcore punk band Black Flag from August 1981 until mid-1986. Following the band's breakup, Rollins established the record label and publishing company 2.13.61 to release his spoken word albums, as well as forming the Rollins Band, which toured with a number of lineups from 1987 until 2003, and during 2006.

Since Black Flag disbanded, Rollins has hosted numerous radio shows, such as Harmony in My Head on Indie 103, and television shows such as The Henry Rollins Show, MTV's 120 Minutes, and Jackass. He had a recurring dramatic role in the second season of Sons of Anarchy and has also had roles in several films. Rollins has also campaigned for various political causes in the United States, including promoting LGBT rights, World Hunger Relief, and an end to war in particular.

Early life

Rollins was born Henry Lawrence Garfield in Washington, D.C.[6] He is the only child of Iris H. Garfield, a federal employee in the health and education sectors,[7] and Paul Jerome Garfield, an economist who is a PhD and published author on the subject.[8][9] When he was three years old, his parents divorced and he was raised by his mother in the affluent Glover Park neighborhood of the city.[6][10][11] His mother taught him how to read before he was enrolled in kindergarten.[12]

As a child and teenager, Rollins suffered from depression and low self-esteem.[13] In the fourth grade, he was diagnosed with hyperactivity and took Ritalin for several years so that he could focus during school. He attended The Bullis School, then an all-male preparatory school in Potomac, Maryland.[6]

According to Rollins, the Bullis School helped him to develop a sense of discipline and a strong work ethic.[13] It was at Bullis that he began writing; his early literary efforts were mainly short stories about "blowing up my school and murdering all the teachers."[12]

Music career

State of Alert

After high school, Rollins attended American University in Washington D.C. for one semester, but dropped out in December 1979.[14] He began working minimum-wage jobs, including a job as a courier for liver samples at the National Institutes of Health.[15] Rollins developed an interest in punk rock after he and his friend Ian MacKaye procured a copy of The Ramones's eponymous debut album; he later described it as a "revelation." From 1979 to 1980, Rollins was working as a roadie for Washington bands, including Teen Idles. When the band's singer Nathan Strejcek failed to appear for practice sessions, Rollins convinced the Teen Idles to let him sing. Word of Rollins's ability spread around the punk rock scene in Washington; Bad Brains singer H.R. would sometimes get Rollins on stage to sing with him.[16]

In 1980, the Washington punk band The Extorts lost their frontman Lyle Preslar to Minor Threat. Rollins joined the rest of the band to form State of Alert, and became its frontman and vocalist. He put words to the band's five songs and wrote several more. S.O.A. recorded their sole EP, No Policy, and released it in 1981 on MacKaye's Dischord Records.[17] S.O.A. disbanded after a total of a dozen concerts and one EP. Rollins had enjoyed being the band's frontman, and had earned a reputation for fighting in shows. He later said: "I was like nineteen and a young man all full of steam [...] Loved to get in the dust-ups." By this time, Rollins had become the manager of the Georgetown Häagen-Dazs ice cream store; his steady employment had helped to finance the S.O.A. EP.[18]

Black Flag

In 1980, a friend gave Rollins and MacKaye a copy of Black Flag's Nervous Breakdown EP. Rollins soon became a fan of the band, exchanging letters with bassist Chuck Dukowski and later inviting the band to stay in his parents' home when Black Flag toured the East Coast in December 1980.[19] When Black Flag returned to the East Coast in 1981, Rollins attended as many of their concerts as he could. At an impromptu show in a New York bar, Black Flag's vocalist Dez Cadena allowed Rollins to sing "Clocked In", as Rollins had a five-hour drive back to Washington, D.C., to return to work after the performance.[20]

Unbeknownst to Rollins, Cadena wanted to switch to guitar, and the band was looking for a new vocalist.[20] The band was impressed with Rollins' singing and stage demeanor, and the next day, after a semi-formal audition at Tu Casa Studio in NYC, they asked him to become their permanent vocalist. Despite some doubts, he accepted, in part because of MacKaye's encouragement. His high level of energy and intense personality suited the band's style, but Rollins' diverse tastes in music were a key factor in his being selected as singer; Black Flag's founder Greg Ginn was growing restless creatively and wanted a singer who was willing to move beyond simple, three-chord punk.[21]

After joining Black Flag in 1981, Rollins quit his job at Häagen-Dazs, sold his car, and moved to Los Angeles. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, Rollins got the Black Flag logo tattooed on his left biceps[15] and chose the stage name of Rollins, a surname he and MacKaye had used as teenagers.[21] Rollins played his first show with Black Flag on August 21, 1981 at Cuckoo's Nest in Costa Mesa, California.[22] Rollins was in a different environment in Los Angeles; the police soon realized he was a member of Black Flag, and he was hassled as a result. Rollins later said: "That really scared me. It freaked me out that an adult would do that. [...] My little eyes were opened big time."[23]

Before concerts, as the rest of the band tuned up, Rollins would stride about the stage dressed only in a pair of black shorts, grinding his teeth; to focus before the show, he would squeeze a pool ball.[24] His stage persona impressed several critics; after a 1982 show in Anacortes, Washington, Sub Pop critic Calvin Johnson wrote: "Henry was incredible. Pacing back and forth, lunging, lurching, growling; it was all real, the most intense emotional experiences I have ever seen."[25]

By 1983, Rollins' stage persona was increasingly alienating him from the rest of Black Flag. During a show in England, Rollins assaulted a member of the audience, who attacked Ginn; Ginn later scolded Rollins, calling him a "macho asshole."[26] A legal dispute with Unicorn Records held up further Black Flag releases until 1984, and Ginn was slowing the band's tempo down so that they would remain innovative. In August 1983, guitarist Dez Cadena had left the band; a stalemate lingered between Dukowski and Ginn, who wanted Dukowski to leave, before Ginn fired Dukowski outright.[27] 1984's heavy metal music-influenced My War featured Rollins screaming and wailing throughout many of the songs; the band's members also grew their hair to confuse the band's hardcore punk audience.[28]

Black Flag's change in musical style and appearance alienated many of their original fans, who focused their displeasure on Rollins by punching him in the mouth, stabbing him with pens, or scratching him with their nails, among other methods. He often fought back, dragging audience members on stage and assaulting them. Rollins became increasingly alienated from the audience; in his tour diary, Rollins wrote "When they spit at me, when they grab at me, they aren't hurting me. When I push out and mangle the flesh of another, it's falling so short of what I really want to do to them."[29] During the Unicorn legal dispute, Rollins had started a weight-lifting program, and by their 1984 tours, he had become visibly well-built; journalist Michael Azerrad later commented that "his powerful physique was a metaphor for the impregnable emotional shield he was developing around himself."[28] Rollins has since replied that "no, the training was just basically a way to push myself."[30]

Rollins Band and solo releases

Before Black Flag disbanded in August 1986, Rollins had already toured as a solo spoken word artist.[31] He released two solo records in 1987, Hot Animal Machine, a collaboration with guitarist Chris Haskett, and Drive by Shooting, recorded as "Henrietta Collins and the Wifebeating Childhaters";[32] Rollins also released his second spoken word album, Big Ugly Mouth in the same year. Along with Haskett, Rollins soon added Andrew Weiss and Sim Cain, both former members of Ginn's side-project Gone, and called the new group Rollins Band. The band toured relentlessly,[33] and their 1987 debut album, Life Time, was quickly followed by the outtakes and live collection Do It. The band continued to tour throughout 1988; 1989 marked the release of another Rollins Band album, Hard Volume.[34] Another live album, Turned On, and another spoken word release, Live at McCabe's, followed in 1990.

1991 saw the Rollins Band sign a distribution deal with Imago Records and appear at the Lollapalooza festival; both improved the band's presence. However, in December 1991, Rollins and his best friend Joe Cole were accosted by two armed robbers outside Rollins's home. Cole was murdered by a gunshot to the head, Rollins escaped without injury but police initially suspected him in the murder and detained him for ten hours.[35] Although traumatized by Cole's death, as chronicled in his book Now Watch Him Die, Rollins continued to release new material; the spoken-word album Human Butt appeared in 1992 on his own record label, 2.13.61. The Rollins Band released The End of Silence, Rollins's first charting album.[34]

The following year, Rollins released a spoken-word double album, The Boxed Life.[36] The Rollins Band embarked upon the End of Silence tour; bassist Weiss was fired towards its end and replaced by funk and jazz bassist Melvin Gibbs. According to critic Steve Huey, 1994 was Rollins's "breakout year".[34] The Rollins Band appeared at Woodstock 94 and released Weight, which ranked on the Billboard Top 40. Rollins released Get in the Van: On the Road with Black Flag, a double-disc set of him reading from his Black Flag tour diary of the same name; he won the Grammy for Best Spoken Word Recording as a result. Rollins was named 1994's "Man of the Year" by the American men's magazine Details and became a contributing columnist to the magazine. With the increased exposure, Rollins made several appearances on American music channels MTV and VH1 around this time, and made his Hollywood film debut in 1994 in The Chase playing a police officer.[37]

In 1995, the Rollins Band's record label, Imago Records, declared itself bankrupt. Rollins began focusing on his spoken word career. He released Everything, a recording of a chapter of his book Eye Scream with free jazz backing, in 1996. He continued to appear in various films, including Heat, Johnny Mnemonic and Lost Highway. The Rollins Band signed to Dreamworks Records in 1997 and soon released Come in and Burn, but it did not receive as much critical acclaim as their previous material. Rollins continued to release spoken-word book readings, releasing Black Coffee Blues in the same year. In 1998, Rollins released Think Tank, his first set of non-book-related spoken material in five years.

By 1998, Rollins felt that the relationship with his backing band had run its course, and the line-up disbanded. He had produced a Los Angeles hard rock band called Mother Superior, and invited them to form a new incarnation of the Rollins Band. Their first album, Get Some Go Again, was released two years later. The Rollins Band released several more albums, including 2001's Nice and 2003's Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs to Benefit the West Memphis Three. After 2003, the band became inactive as Rollins focused on radio and television work. During a 2006 appearance on Tom Green Live!, Rollins stated that he "may never do music again"[38] a feeling which he reiterated in 2011 when talking to Trebuchet magazine.[39] In an interview with Culture Brats, Henry admitted he had sworn off music for good – "... and I must say that I miss it every day. I just don't know honestly what I could do with it that's different."[40]

Musical style

As a vocalist, Rollins has adopted a number of styles through the years. Rollins was initially noted in the Washington, D.C. hardcore scene for what journalist Michael Azerrad described as a "compelling, raspy howl."[16] With State of Alert, Rollins "spat out the lyrics like a bellicose auctioneer."[18] He adopted a similar style after joining Black Flag in 1981. By their album Damaged, however, Black Flag began to incorporate a swing beat into their style. Rollins then abandoned his S.O.A. "bark" and adopted the band's swing.[41] Rollins later explained: "What I was doing kind of matched the vibe of the music. The music was intense and, well, I was as intense as you needed."[42]

In both incarnations of the Rollins Band, Rollins combined spoken word with his traditional vocal style in songs such as "Liar" (the song begins with a one-minute spoken diatribe by Rollins), as well as barking his way through songs (such as "Tearing" and "Starve") and employing the loud-quiet dynamic. Rolling Stone's Anthony DeCurtis names Rollins a "screeching hate machine" and his "hallmark" as "the sheets-of-sound assault".[43]

With the Rollins Band, his lyrics focused "almost exclusively on issues relating to personal integrity," according to critic Geoffrey Welchman.[44]

As producer

In the 1980s, Henry Rollins produced an album of acoustic songs for the famed convict Charles Manson titled Completion. The record was supposed to be released by SST Records, but the project was later canceled due to the label receiving death threats for working with Manson. Only five test presses of Completion were pressed, two of which remain in Rollins' possession.[45]

Joe Cole

Rollins and his best friend Joe Cole were involved in a shooting when they were assaulted by robbers in December 1991 outside their shared Venice Beach, California home where Cole was killed after being shot in the face while Rollins escaped.[46] The murder remains unsolved.[47]

In a 1992 Los Angeles Times interview Rollins revealed he kept a plastic container full of soil soaked with the blood of Joe Cole. Rollins said "I dug up all the earth where his head fell—he was shot in the face—and I've got all the dirt here, and so Joe Cole's in the house. I say good morning to him every day. I got his phone, too, so I got a direct line to him. So that feels good."[46]

Rollins went on to include Cole's story in his spoken word performances.[48]

Media work

Television

As Rollins rose to prominence with the Rollins Band, he began to present and appear on television. These included Alternative Nation and MTV Sports in 1993 and 1994 respectively. 1995 saw Rollins appear on an episode of Unsolved Mysteries that explored the murder of his best friend Joe Cole[49] and present State of the Union Undressed on Comedy Central. Rollins began to present and narrate VH1 Legends in 1996.[50] Rollins, busy with the Rollins Band, did not present more programs until 2001, but made appearances on a number of other television shows, including Welcome to Paradox in 1998 in the episode "All Our Sins Forgotten", as a therapist that develops a device that can erase the bad memories of his patients. Rollins also voiced Mad Stan in Batman Beyond in 1999 and 2000.[51][52]

Rollins was a host of film review programme Henry's Film Corner on the Independent Film Channel, before presenting the weekly The Henry Rollins Show on the channel. The Henry Rollins Show is now being shown weekly on Film24 along with Henry Rollins Uncut. The show also lead to a promotional tour in Europe that led to Henry being dubbed a “bad boy goodwill ambassador” by a NY reviewer.[53]

2002 saw Rollins guest star on an episode of the sitcom The Drew Carey Show as a man whom Oswald would find on eBay and pay to come to his house and "kick his ass". He co-hosted the British television show Full Metal Challenge, in which teams built vehicles to compete in various driving and racing contests, from 2002–2003 on Channel 4 and TLC. He has made a number of cameo appearances in television series such as MTV's Jackass and an episode of Californication, where he played himself hosting a radio show.[54] In 2006, Rollins appeared in a documentary series by VH1 and The Sundance Channel called The Drug Years.[55]

Rollins appears in FX's Sons of Anarchy's second season, which premiered in the fall of 2009 in the United States. Rollins plays A.J. Weston, a white-supremacist gang leader and new antagonist in the show's fictional town of Charming, California, who poses a deadly threat to the Sons of Anarchy Motorcycle Club.[56] In 2009, Rollins voiced "Trucker" in American Dad!'s fourth season (episode eight).[57] Rollins voiced Benjamin Knox/Bonk in the 2000 animated film Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker.[58]

In 2010, Rollins appeared as a guest judge on Season 2 episode 6 of RuPaul's Drag Race.[59][60]

In 2011, Rollins was interviewed in the National Geographic Explorer episode "Born to Rage", regarding his possible link to the MAO gene (warrior gene) and violent behavior.[61]

In 2012, Rollins hosted the National Geographic Wild series "Animal Underworld", investigating where the real boundaries lay in human-animal relationships.[62]

Rollins is currently doing voiceover work in a series of television commercials for Infiniti, the luxury automobile brand.[63]

On November 2, 2013, Rollins started hosting the show 10 Things You Don't Know About on the History Channel's H2.[64]

Radio

On May 19, 2004, Rollins began hosting a weekly radio show, Harmony in My Head, on Indie 103.1 radio in Los Angeles. The show aired every Monday evening, with Rollins playing music ranging from early rock and jump blues to hard rock, blues rock, folk rock, punk rock, heavy metal and rockabilly, and touching on hip hop, jazz, world music, reggae, classical music and more. Harmony in my Head often emphasizes B-sides, live bootlegs and other rarities, and nearly every episode has featured a song either by the Beastie Boys or British group The Fall.

Rollins put the show on a short hiatus to undertake a spoken-word tour in early 2005. Rollins posted playlists and commentary on-line; these lists were expanded with more information and published in book form as Fanatic! through 2.13.61 in November 2005. In late 2005, Rollins announced the show's return and began the first episode by playing the show's namesake Buzzcocks song. As of 2008, the show continues each week despite Rollins's constant touring with new pre-recorded shows between live broadcasts. In 2009 Indie 103.1 went off the air, although it continues to broadcast over the Internet.

In 2007, Rollins published Fanatic! Vol. 2 through 2.13.61. Fanatic! Vol. 3 was released in the fall of 2008. On February 18, 2009, KCRW announced that Rollins would be hosting a live show on Saturday nights starting March 7, 2009.[65] In 2011 Rollins was interviewed on Episode 121 of American Public Media's podcast, "The Dinner Party Download", posted on November 3, 2011.

Film

Rollins began his film career appearing in several independent films featuring the band Black Flag. His film debut was in 1982's The Slog Movie, about the West Coast punk scene.[66] An appearance in 1985's Black Flag Live followed. Rollins' first film appearance without Black Flag was the short film The Right Side of My Brain with Lydia Lunch in 1985.[67] Following the band's breakup, Rollins did not appear in any films until 1994's The Chase. Rollins appeared in the 2007 direct-to-DVD sequel to Wrong Turn (2003), Wrong Turn 2: Dead End as a retired Marine Corps officer who hosts his own show which tests the contestants' will to survive. Rollins has also appeared in Punk: Attitude, a documentary on the punk scene, and in American Hardcore (2006). In 2012, Henry Rollins appeared in a short documentary entitled "Who Shot Rock and Roll" discussing the early punk scene in Los Angeles as well as photographs of himself in Black Flag taken by esteemed photographer Edward Colver.[68]

Some feature length movies Henry Rollins has appeared in include:

- Kiss Napoleon Goodbye (1990), with Lydia Lunch and Don Bajema

- The Chase (1994), with Charlie Sheen

- Johnny Mnemonic (1995), with Keanu Reeves, Ice-T and Dolph Lundgren

- Heat (1995), with Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Val Kilmer

- Lost Highway (1997), with Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette; directed by David Lynch

- Jack Frost (1998), with Michael Keaton

- Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker (2000), with Kevin Conroy and Mark Hamill

- Morgan's Ferry (2001), with Billy Zane and Kelly McGillis

- Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001 documentary)

- Scenes of the Crime (2001), with Jeff Bridges

- The New Guy (2002), with Tommy Lee and DJ Qualls

- Jackass The Movie (2002) with Johnny Knoxville and Bam Margera

- Bad Boys II (2003) with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence

- Deathdealer: A Documentary (2004)

- Feast (2005), with Balthazar Getty and Navi Rawat

- Jackass Number Two (2006), with Preston Lacy, Steve-O and Chris Pontius

- The Alibi (2006)

- Wrong Turn 2: Dead End (2007)

- The Devil's Tomb (2009)

- H for Hunger (2009 documentary)

- William Shatner's Gonzo Ballet (2009 documentary)

- Green Lantern: Emerald Knights (2011) as Kilowog

- West of Memphis (2012 documentary)

- Downloaded (2013 documentary)

- He Never Died (2014) Currently in production. With Steven Ogg and Booboo Stewart[69]

Books and audiobooks

Rollins has written a variety of books, including Black Coffee Blues, Do I Come Here Often?, The First Five (a compilation of High Adventure in the Great Outdoors, Pissing in the Gene Pool, Bang!, Art to Choke Hearts, and One From None), See a Grown Man Cry, Now Watch Him Die, Smile, You're Traveling, Get in the Van, Eye Scream, Broken Summers, Roomanitarian, and Solipsist.

For the audiobook version of the 2006 novel World War Z Rollins voiced the character of T. Sean Collins, a mercenary hired to protect celebrities during a mass panic caused by an onslaught of the undead. Rollins' other audiobook recordings include 3:10 to Yuma and his own autobiographical book Get in the Van, for which he won a Grammy Award.

Online journalism

In September 2008, Rollins began contributing to the "Politics & Power" blog at the online version of Vanity Fair magazine.[70] Since March 2009, his posts have appeared under their own sub-title, Straight Talk Espresso.[71] His posts consistently direct harsh criticism at conservative politicians and pundits, although he does occasionally target those on the left.[citation needed] In August 2010, he began writing a music column for LA Weekly, an alternative newspaper in Los Angeles.[1] In 2012, Rollins began publishing articles with The Huffington Post and alternative news website WordswithMeaning!. In the months leading up to the 2012 United States Presidential election, Rollins broadcast a YouTube series called "Capitalism 2012", in which he toured the capital cities of the US states, interviewing people about current issues.[citation needed]

Spoken word

Rollins also has toured doing spoken word performances which range from stand up comedy to more introspective commentaries on his childhood, such as the death of his friend, Joe Cole. He also speaks about experiences he's had with eccentric people. Rollins' spoken word style varies greatly, ranging from intense commentaries on society to playful, sometimes vulgar, anecdotes.

Video games

Rollins was a playable character in both Def Jam: Fight for NY and Def Jam Fight for NY: The Takeover. Rollins is also the voice of Mace Griffin in Mace Griffin: Bounty Hunter.

Campaigning and activism

Rollins has become an outspoken human rights activist, most vocally for gay rights. Rollins frequently speaks out on social justice on his spoken word tours and promotes equality, regardless of sexuality.[72] He was the host of the WedRock benefit concert, which raised money for a pro-gay-marriage organization.

During the 2003 Iraq War, he started touring with the United Service Organizations to entertain troops overseas while remaining against the war, leading him to once cause a stir at a base in Kyrgyzstan when he told the crowd: "Your commander would never lie to you. That's the vice president's job."[73] Rollins believes it is important that he performs to the troops so that they have multiple points of contact with the rest of the world, stating that "they can get really cut loose from planet earth."[74] He has made 8 tours, including visits to bases in Djibouti, Kuwait, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan (twice), Egypt, Turkey, Qatar, Honduras, Japan, Korea and the United Arab Emirates.[75]

He has also been active in the campaign to free the "West Memphis Three"—three young men who were believed by their supporters to have been wrongfully convicted of murder, and who have since been released from prison, but not exonerated. Rollins appears with Public Enemy frontman Chuck D on the Black Flag song "Rise Above" on the benefit album Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs to Benefit the West Memphis Three, the first time Rollins had performed Black Flag's material since 1986.[76]

Continuing his activism on behalf of US troops and veterans, Rollins joined Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) in 2008 to launch a public service advertisement campaign, CommunityofVeterans.org, which helps veterans coming home from war reintegrate into their communities. In April 2009, Rollins helped IAVA launch the second phase of the campaign which engages the friends and family of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans at SupportYourVet.org.

On December 3, 2009, Rollins wrote of his support for the victims of the Bhopal disaster in India, in an article for Vanity Fair[77] 25 years–to the day–after the methyl isocyanate gas leak from the Union Carbide Corporation's pesticide factory exposed more than half a million local people to poisonous gas and resulted in the death of 17,000. He spent time in Bhopal with the people, to listen to their stories. In a later radio interview in February 2010[78] Rollins summed up his approach to activism, "This is where my anger takes me, to places like this, not into abuse but into proactive, clean movement."[79]

Works

Work with State of Alert

- No Policy (1981)

- three songs on the sampler Flex Your Head (1982)

Work with Black Flag

- Damaged (1981)

- My War (1984)

- Family Man (1984)

- Slip It In (1984)

- Loose Nut (1985)

- In My Head (1985)

Studio albums (Solo)

- Hot Animal Machine (1987)

- Drive by Shooting (1987)

Work with Wartime (Weiss, Rollins)

- Fast Food for Thought (1990)

- "Franklin's Tower" on the tribute album Stolen Roses: Songs of the Grateful Dead (2000)

Studio albums with Rollins Band

- Life Time (1987, re-release 1999)

- Do It (1987)

- Hard Volume (1989, re-release 1999)

- The End of Silence (1992, double-CD re-release 2002)

- Weight (1994)

- Come In and Burn (1997)

- Get Some Go Again (2000)

- Nice (2001)

- Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs to Benefit the West Memphis Three (2002)

Spoken word

- Short Walk on a Long Pier (1985)

- Big Ugly Mouth (1987)

- Sweatbox (1989)

- Live at McCabe's (1990)

- Human Butt (1992)

- The Boxed Life (1993)

- Think Tank (1998)

- Eric the Pilot (1999)

- A Rollins in the Wry (2001)

- Live at the Westbeth Theater (2001)

- Talk Is Cheap: Volume 1 (2003)

- Talk Is Cheap: Volume 2 (2003)

- Talk Is Cheap: Volume 3 (2004)

- Talk Is Cheap: Volume 4 (2004)

- Provoked (2008)

- Spoken Word Guy (2010)

- Spoken Word Guy 2 (2010)

Spoken word documentaries

- Talking from the Box (1993)

- Henry Rollins Goes to London (1995)

- You Saw Me Up There (1998)

- Up for It (2001)

- Live at Luna Park (2004)

- Shock & Awe: The Tour (2005)

- Uncut from NYC (2007)

- Uncut from Israel (2007)

- San Francisco 1990 (2007)

- Live in the Conversation Pit (2008)

Audio books

- Get in the Van: On the Road with Black Flag (1994)

- Everything (1996)

- Black Coffee Blues (1997)

- Nights Behind the Tree Line (2004)

Guest appearances and collaborations

| Song | Artist | Album | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| "We Are 138" | Misfits | Evilive | 1982 |

| "Kick Out the Jams" | Bad Brains | Pump Up the Volume Soundtrack | 1990 |

| "Let There Be Rock" | Hard-Ons | Released as a single | 1991 |

| "Bottom" | Tool | Undertow | 1993 |

| "Wild America" | Iggy Pop | American Caesar | 1993 |

| "Sexual Military Dynamics" | Mike Watt | Ball-Hog or Tugboat? | 1995 |

| "Delicate Tendrils" | Les Claypool and the Holy Mackerel | Highball with the Devil | 1996 |

| "T-4 Strain" | Goldie | Spawn: The Album | 1997 |

| "War" | Bone Thugs-n-Harmony & Edwin Starr | Small Soldiers | 1998 |

| "Laughing Man (In the Devil Mask)" | Tony Iommi | Iommi | 2000 |

| "I Can't Get Behind That" | William Shatner | Has Been | 2004 |

| All tracks | The Flaming Lips | The Flaming Lips and Stardeath and White Dwarfs with Henry Rollins and Peaches Doing the Dark Side of the Moon | 2009 |

Essays

- As We See It, an editorial essay in Stereophile magazine.[80]

References

- ^ a b Rollins, Henry (August 20, 2010). "Fanatics! Meet LA Weekly's New Columnist: Henry Rollins". LA Weekly. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Henry Rollins - Tours at Undertheradar". Undertheradar.co.nz. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Henry Rollins: 'I Like Stress; It Keeps Me Rockin''". Blabbermouth.net. December 30, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Henry Rollins - KCRW 89.9 FM | Internet Public Radio Station Streaming Live Independent Music & NPR News". Kcrw.com. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Radar: Henry Rollins, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Gilberto Gil, What Disturbs Our Blood, Light the Dark". Blogto.com. November 19, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c J. Parker, Turned On: A Biography of Henry Rollins, 2000

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Life on road suits Rollins fine". The News Times (Danbury, CT).

- ^ "An Unofficial Henry Rollins & Rollins Band Website". Come In And Burn. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Rolling Stone Interview: Henry Rollins". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Alexandria Sightings – Nature or nurture? Henry Rollins provokes | Alexandria Times". Alextimes.com. September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Ayad, Neddal (February 9, 2007). ""You can't dance to a book:" Neddal Ayad interviews Henry Rollins". TheModernWord.com.

- ^ a b Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991. Little Brown and Company, 2001. ISBN 0-316-78753-1. p. 25

- ^ "An Interview With Henry Rollins | The Daily". Dailyuw.com. November 27, 1996. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Sklar, Ronald. "Henry Rollins interview". PopEntertainment.com. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ a b Azerrad, 2001. p. 26

- ^ DePasquale, Ron. "State of Alert > Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Azerrad, 2001. p. 27

- ^ Azzerad, 2001. p. 27-28

- ^ a b Azerrad, 2001. p. 28

- ^ a b Azerrad, 2001. p. 29

- ^ "Black Flag at the Cuckoo's Nest". It All Happened - A Living History of Live Music.

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 31

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 34

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 38

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 39

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 41

- ^ a b Azerrad, 2001. p. 47

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 46

- ^ Jensen, Erik (April 3, 2008). "Henry Rollins interview". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ Waggoner, Eric. "Lip Service – Henry Rollins". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank. "Henry Rollins/Black Flag". Survey of American Popular Music. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Rollins Band > Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c Huey, Steve. "Henry Rollins > Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ Carvin, Andy; Crone, Chris. "Primal Scream: Henry Rollins speaks". EdWebProject.org. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Boxed Life > Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- ^ "Henry Rollins Biography". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ "Henry Rollins on 'Tom Green Live'". Blabbermouth.net. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ "Henry Rollins:Student Protests are Great". Trebuchet Magazine. January 11, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ "Tramp The Last Mile: Our Interview With Henry Rollins". Culture Brats. March 8, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 32

- ^ Azerrad, 2001. p. 33

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony. "Rollins Band: Get Some Go Again". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ Welchman, Geoffrey. "Rollins Band: Weight". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ Luerssen, John D. (December 15, 2010). "Henry Rollins Reveals He Produced Charles Manson Album". Spinner. AOL Music. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ a b "Singer-Poet Henry Rollins Fuels His Art With Rage - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. January 12, 1999. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (November 23, 2009). "Dennis Cole, 'Felony Squad' Actor, Is Dead at 69". The New York Times.

- ^ Bromley, Patrick (May 6, 2004). "Henry Rollins: Live At Luna Park". DVD Verdict.

- ^ "Joe Cole". Unsolved Mysteries. Season 8. Episode 376. May 17, 1996. NBC.

- ^ "Henry Rollins Biography (1961–)". FilmReference.com. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ^ "Rats!". Batman Beyond. Season 2. Episode 22. November 20, 1999. The WB.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "Eyewitness". Batman Beyond. Season 2. Episode 27. January 22, 2000. The WB.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Winston, Rory (April 2009). "Our Man Rollins". NY Resident Magazine. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ "LOL". Californication. Season 1. Episode 5. September 10, 2007. Showtime.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "Shows : Rock Docs : The Drug Years : Featured Artists". VH1. March 16, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "SOA Season 2". Soa.blogs.fxnetworks.com. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "American Dad! Episode Guide 2009 Season 4 - Chimdale, Episode 8". tvguide.com. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Deathfrogurt (September 18, 2009). "Henry Rollins To Join The Doom Patrol In 'Batman: The Brave And The Bold' – ComicsAlliance | Comics culture, news, humor, commentary, and reviews". ComicsAlliance. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "Episode 6, Season 2: Rocker Chicks | Video Clips, Watch Full Episodes Online". Logotv.com. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Henry Rollins Turned On By RuPaul's Drag Race". Jezebel.com. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Henry Rollins, 'Born to Rage' hunt anger's genetic roots". USA Today. December 13, 2010.

- ^ National Geographic Wild. "Animal Underworld".

- ^ cars.com. "Henry Rollins: Infiniti's Hardcore Voiceover Man".

- ^ "Henry Rollins - 10 Things You Don't Know About Cast". HISTORY.com. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Pop & Hiss". Los Angeles Times. February 18, 2009.

- ^ "The Slog Movie (1982)". Imdb.com. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ "The Right Side of My Brain (1985)". Imdb.com. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "Who Shot Rock and Roll Official Trailer". Who Shot Rock and Roll.

- ^ "Henry Rollins Wraps First Lead Film Role". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Rollins, Henry (September 9, 2008). "Are We Really Going to Elect Sleepy John?". VF Daily's Politics & Power Blog. Condé Nast Digital. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "The Nancy Reagan Stem Cell Research Good Time Hour Presents ..." VF Daily's Politics & Power Blog. Condé Nast Digital. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Rollins, Henry (June 1, 2007). "Henry Rollins". InstinctMagazine.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Kasindorf, Martin; Komarow, Steven (December 22, 2005). "USO cheers troops, but Iraq gigs tough to book". USA Today. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

Rollins, 44, has made six USO tours. The former lead singer for the punk-rock group Black Flag said that he generally keeps his anti-war views to himself at USO shows.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Henry Rollins Interview". Crasier Frane. June 20, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "The USO (United Services Organizations) « Henry Rollins' Causes". Rollinscauses.wordpress.com. November 28, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs to Benefit the West Memphis Three". Allmusic. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Twenty-five Years After the Disaster, Bhopal Is Still Ill". Vanity Fair. December 3, 2009.

- ^ "Henry Rollins on positive anger – audio interview with Jennifer Davies (2 mins)". Jennifer-davies.com. February 5, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "Henry Rollins radio interview with World Radio Switzerland (10 mins)". Worldradio.ch. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ Rollins, Henry (2011). "As We See It". Stereophile. 34 (8). Source Interlink Media: 1.

Further reading

- Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991. Little Brown and Company, 2001. ISBN 0-316-78753-1

External links

- Official website

- Interview with Henry Rollins on PMAKid.com

- Straight Talk Espresso, Rollins's blog at VanityFair.com

- Henry Rollins at IMDb

- IFC Site for The Henry Rollins Show

- Template:Wayback, Dan O'Mahony, "Point Nine Nine", November 7, 2011

- Henry Rollins, episode #14 of By The Way, In Conversation With Jeff Garlin on Earwolf, July 11, 2013

- "RuPaul Drives Henry Rollins" review of web series Rocker Magazine 2013

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1961 births

- Living people

- Male actors from Washington, D.C.

- Alternative metal musicians

- American activist journalists

- American anarchists

- American anti–Iraq War activists

- American anti-war activists

- American dissidents

- American atheists

- American bloggers

- American book publishers (people)

- American male film actors

- American anti-fascists

- American heavy metal singers

- American human rights activists

- American male singers

- American writers

- American public radio personalities

- American punk rock singers

- American male voice actors

- American spoken word artists

- American stand-up comedians

- American male television actors

- Anti-corporate activists

- Anti-racism activists

- Audio book narrators

- Black Flag (band) members

- Grammy Award-winning artists

- LGBT rights activists from the United States

- Musicians from Washington, D.C.

- Songwriters from Washington, D.C.

- People from the Washington metropolitan area

- People from Washington, D.C.