Indigenous peoples in Venezuela

Indigenous people in Venezuela, Amerindians or Native Venezuelans, form about 2% of the population of Venezuela,[1] although many Venezuelans are mixed with Indigenous ancestry. Indigenous people are concentrated in the Southern Amazon rainforest state of Amazonas, where they make up nearly 50% of the population[1] and in the Andes of the western state of Zulia. The most numerous indigenous people, at about 200,000, is the Venezuelan part of the Wayuu (or Guajiro) people who primarily live in Zulia between Lake Maracaibo and the Colombian border.[2] Another 100,000 or so indigenous people live in the sparsely populated southeastern states of Amazonas, Bolívar and Delta Amacuro.[2]

There are at least 30 indigenous groups in Venezuela, including the Wayuu (413,000), Warao people (36,000), Ya̧nomamö (35,000), Kali'na (34,000), Pemon (30,000), Anu͂ (21,000), Huottüja (15,000), Motilone Barí, Ye'kuana[2] and Yaruro.

History

[edit]

Around 13 000 BCE human settlement in the actual Venezuela were the Archaic pre-ceramic populations that dominated the territory until about 200 BCE. Archeologists have discovered evidence of the earliest known inhabitants of the Venezuelan area in the form of leaf-shaped flake tools, together with chopping and scraping implements exposed on the high riverine terraces of the Pedregal River in western Venezuela.[3] Late Pleistocene hunting artifacts, including spear tips, come from a similar site in northwestern Venezuela known as El Jobo. According to radiocarbon dating, these date from 13,000 to 7000 BCE.[4] Taima-Taima, yellow Muaco and El Jobo in Falcón State are some of the sites that have yielded archeological material from these times.[5] These groups co-existed with megafauna like megatherium, glyptodonts and toxodonts. The Manicuaroids pre-ceramic communities was formed, primarily in Punta Gorda and Manicuare that followed one another on the islands of the Margarita and Cubagua, off the eastern coast of Venezuela, and that seem to constitute a unique cultural tradition.The bone point, shell gouge, and two-pronged stone are characteristic in this places. About 5000 BCE, the archaeological site at Banwari Trace in southwestern Trinidad island is the oldest pre-Columbian site in the West Indies. At this time, Trinidad was still part of South America. Archaeological research of the site has also shed light on the patterns of migration of this pre ceramic peoples from mainland actual Eastern Venezuela to the Lesser Antilles between 5000 and 2000 BCE. In this period, hunters and gatherers of megafauna started to turn to other food sources and established the first tribal structures. The first ceramic-using people in Venezuelan were the Saladoid indigenous, an Arawak people that flourished from 500 BCE to 545 CE. The Saladoid were concentrated along the lowlands of the Orinoco River. Around 250 BCE entered Trinidad and Tobago to later moved north into the remaining islands of the Caribbean sea until Cuba and the Bahamas. After 250 CE a third group, called the Barrancoid people migrating up the Orinoco River toward Trinidad and other island of the Antilles navigating in wooden canoes. Following the collapse of Barrancoid communities along the Orinoco around 650 CE, a new group, called the Arauquinoid expanded up the river to the coast. The cultural artifacts of this group were encountered in the northeast Venezuela and only partly adopted in Trinidad and adjacent islands, and as a result, this culture is called Guayabitoid in these areas. The Timoto-Cuica culture was the most complex society in Pre-Columbian Venezuela; with pre-planned permanent villages, surrounded by irrigated, terraced fields and with tanks for water storage.[6] Their houses were made primarily of stone and wood with thatched roofs. They were peaceful, for the most part, and depended on growing crops. Regional crops included potatoes and ullucos.[7] They left behind works of art, particularly anthropomorphic ceramics, but no major monuments. They spun vegetable fibers to weave into textiles and mats for housing. They are credited with having invented the arepa, a staple of Venezuelan cuisine.[8] Around 1300 CE the Caribs, a new group appears to have settled in the Coast Range and Orinoco Delta where introduced new cultural attributes which largely replaced the Guayabitoid culture. Termed the Mayoid cultural tradition, dividing their territory with the Arawak, against whom they fought during their expansion toward the east and navigating the Lesser Antilles until Puerto Rico. They were prolific travelers even though they weren't nomads, This represents the native indigenous which were present in 1498 when Christopher Columbus's arrival at Venezuela. Their distinct pottery and artifacts survive until 1800, but after this time they were largely assimilated into mainstream. It is not known how many people lived in Venezuela before the Spanish Conquest; it may have been around a million people[9] and in addition to today's peoples included groups such as the Arawaks, Caribs, and Timoto-cuicas the Auaké, Caquetio, Mariche, Pemon, and Piaroa.[10] The number was much reduced after the Conquest, mainly through the spread of new diseases from Europe.[9] There were two main north-south axes of pre-Columbian population, producing maize in the west and manioc in the east.[9] Large parts of the Llanos plains were cultivated through a combination of slash and burn and permanent settled agriculture.[9] The indigenous peoples of Venezuela had already encountered crude oils and asphalts that seeped up through the ground to the surface. Known to the locals as mene, the thick, black liquid was primarily used for medicinal purposes, as an illumination source and for the caulking of canoes.[11] In the islands of Cubagua and Margarita off the northeastern coast of Venezuela the indigenous people as expert divers harvesting the pearls that normally used as ceremonnial ornaments.

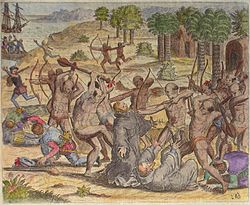

Spain's colonization of mainland Venezuela started in 1514, establishing its first permanent South American settlement in the present-day[update] city of Cumaná. The name "Venezuela" is said to derive from palafito villages discovered in 1499 on Lake Maracaibo reminding Amerigo Vespucci of Venice (hence "Venezuela" or "little Venice").[12] Amerindian caciques (leaders) such as Guaicaipuro (circa 1530–1568) and Tamanaco (died 1573) attempted to resist Spanish incursions, but the newcomers ultimately subdued them. Historians agree that the founder of Caracas, Diego de Losada, ultimately put Tamanaco to death.[13] Some of the resisting tribes or the leaders are commemorated in place names, including Caracas, Chacao and Los Teques. The early colonial settlements focussed on the northern coast,[9] but in the mid-eighteenth century the Spanish pushed further inland along the Orinoco River. Here the Ye'kuana (then known as the Makiritare) organised serious resistance in 1775 and 1776.[14] Under Spanish colonization, several religious orders established mission stations. The Jesuits withdrew in the 1760s, while the Capuchins found their missions of strategic significance in the War of Independence and in 1817 were brutally taken over by the forces of Simon Bolivar.[14] For the remainder of the nineteenth century governments did little for indigenous peoples and they were pushed away from the country's agricultural centre to the periphery.[14]

In 1913, during a rubber boom, Colonel Tomas Funes seized control of Amazonas's San Fernando de Atabapo, killing over 100 settlers. In the following nine years in which Funes controlled the town, Funes destroyed dozens of Ye'kuana villages and killed several thousand Ye'kuana.[15][16]

In October 1999, Pemon destroyed a number of electricity pylons constructed to carry electricity from the Guri Dam to Brazil. The Pemon argued that cheap electricity would encourage further development by mining companies. The $110 million project was completed in 2001.[15]

Political organization

[edit]The National Council of Venezuelan Indians (Consejo Nacional Indio de Venezuela, CONIVE) was formed in 1989 and represents the majority of indigenous peoples, with 60 affiliates representing 30 peoples.[17] In September 1999, indigenous peoples "marched on the National Congress in Caracas to pressure the Constitutional Assembly for the inclusion of important pro-[indigenous] provisions in the new constitution, such as the right to ownership, free transit across international borders, free choice of nationality, and land demarcation within two years."[18]

Legal rights

[edit]Prior to the creation of the 1999 constitution of Venezuela, legal rights for indigenous peoples were increasingly lagging behind other Latin American countries, which were progressively enshrining a common set of indigenous collective rights in their national constitutions.[19] The 1961 constitution had actually been a step backward from the 1947 constitution, and the indigenous rights law foreseen in it languished for a decade, unpassed by 1999.[19]

Ultimately the 1999 constitutional process produced "the region's most progressive indigenous rights regime".[20] Innovations included Article 125's guarantee of political representation at all levels of government and Article 124's prohibition on "the registration of patents related to indigenous genetic resources or intellectual property associated with indigenous knowledge."[20] The new constitution followed the example of Colombia in reserving parliamentary seats for indigenous delegates (three in Venezuela's National Assembly) and it was the first Latin American constitution to reserve indigenous seats in state assemblies and municipal councils in districts with indigenous populations.[21]

Languages

[edit]The main language families are

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Van Cott (2003), "Andean Indigenous Movements and Constitutional Transformation: Venezuela in Comparative Perspective", Latin American Perspectives 30(1), p52

- ^ a b c Richard Gott (2005), Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution, Verso. p202

- ^ Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of archaeology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. p. 91. ISBN 0-306-46158-7.

- ^ Kipfer 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (Eds.) (2008): Handbook of South American Archaeology 1st ed. 2008. Corr. 2nd printing, XXVI, 1192 p. 430 .ISBN 978-0-387-74906-8. Pg 433-434

- ^ Mahoney 89

- ^ "Venezuela." Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Friends of the Pre-Columbian Art Museum. (retrieved 9 July 2011)

- ^ Gilbert G. Gonzalez; Raul A. Fernandez; Vivian Price; David Smith; Linda Trinh Võ (2 August 2004). Labor Versus Empire: Race, Gender, Migration. Routledge. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-1-135-93528-3.

- ^ a b c d e Wunder, Sven (2003), Oil wealth and the fate of the forest: a comparative study of eight tropical countries, Routledge. p130.

- ^ Others include the Aragua and Tacariguas, from the area around Lake Valencia.

- ^ Anibal Martinez (1969). Chronology of Venezuelan Oil. Purnell and Sons LTD.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2005). Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan. Random House. p. 189. ISBN 0-375-50204-1.

- ^ "Alcaldía del Hatillo: Historia" (in Spanish). Universidad Nueva Esparta. Archived from the original on 28 April 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Gott (2005:203)

- ^ a b Gott (2005:204)

- ^ See Los Hijos de La Luna: Monografia Anthropologica Sobre los Indios Sanema-Yanoama, Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Arte, 1974

- ^ Van Cott, Donna Lee (2006), "Turning Crisis into Opportunity: Achievements of Excluded Groups in the Andes", in Paul W. Drake, Eric Hershberg (eds), State and society in conflict: comparative perspectives on Andean crises, University of Pittsburgh Press. p.163

- ^ Alcida Rita Ramos, "Cutting through state and class: Sources and Strategies of Self-Representation in Latin America", in Kay B. Warren and Jean Elizabeth Jackson (eds, 2002), Indigenous movements, self-representation, and the state in Latin America, University of Texas Press. pp259-60

- ^ a b Van Cott (2003), "Andean Indigenous Movements and Constitutional Transformation: Venezuela in Comparative Perspective", Latin American Perspectives 30(1), p51

- ^ a b Van Cott (2003:63)

- ^ Van Cott (2003:65)