London Protocol (1830)

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (May 2022) |

| |

| Context | The first official, international diplomatic act recognizing Greece as a sovereign and independent state with all the rights - political, administrative, commercial - deriving from its independence, which would extend south of the border line defined by the rivers Acheloos and Sperchios. |

|---|---|

| Signed | February 3, 1830 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Parties | |

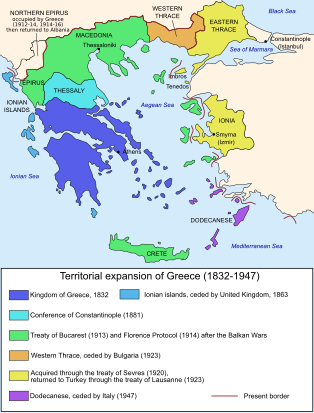

The 1830 Protocol of London was a treaty signed between the Kingdom of France, the Russian Empire, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on February 3, 1830. It was the first official, international diplomatic act recognizing Greece as a sovereign and independent state, with all the rights - political, administrative, and commercial - that derived from its independence, which would extend south of the border defined by the rivers Achelous and Spercheios. The first governor of the newly-formed state (1830-1831) was Ioannis Kapodistrias, who had already previously served as governor of Greece in 1828 following a resolution of the Third National Assembly at Troezen.

The London Protocol also determined that the Greek state would be a monarchy and its ruler would have the title "Ruler Sovereign of Greece". For the position of monarch, the contracting countries initially selected Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (later elected Leopold I, King of the Belgians) who, despite his initial acceptance, ultimately declined their proposal.

After the Leopold's decision to decline the offer of the Greek throne[1] and the assassination of Kapodistrias, a new treaty, signed April 25 / May 7, 1832, named the 17-year-old Prince Otto of Bavaria as the King of Greece and designated the new state the Kingdom of Greece. The selection of Otto as king, which was influenced by the philhellenism of his father, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, was not fully agreed upon the three great powers, notably the United Kingdom.

Course to the Protocol of Independence

From George Canning to the Battle of Navarino

After 1823, due to UK Prime Minister George Canning, the Greek issue appeared in European diplomacy, as the main intention of the British Foreign Secretary was the international recognition of Greece, in order to stop Russia's route towards the Aegean Sea.[2]

- January 1824: Russia proposed the Plan of the Three Departments: Three principalities would be created according to the model of the Danube Principalities: Eastern Greece, Epirus and Aetolia-Acarnania, Peloponnese and Crete. This plan did not satisfy the Greeks who were fighting for independence.[3]

- June 1825: Act of Vassalage. Under the pressure of Ibrahim's victories in the Peloponnese, the Koundouriotis government asked the British government to choose a monarch for Greece, stating its preference for Leopold of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha. With this Act, they essentially asked for Greece to become an English protectorate, as a sign of confidence in England. George Canning, however, refused to accept the Act.[4]

- April 1826: The Protocol of St. Petersburg was signed, which referred to an Anglo-Russian cooperation in resolving the Greek Issue by providing autonomy to the Greeks. In fact, this is the first text that recognizes the political existence of Greece.[5]

The terms of the St. Petersburg Protocol were repeated in the Treaty of London (July 1827), which was also signed by France. A secret "supplementary" article also provided for military coercion on both sides, mainly Turkey, in order to accept the terms of the Treaty.[6]

This article would lead to the Battle of Navarino (7/20 October 1827). The defeat of the Turkish fleet by the fleets of the three Great Powers (England, France, Russia) caused excitement and gave hope to the Greeks, although the European powers only spoke for autonomy - not yet independence - of certain regions, so as to appease the area.

Change of English policy and delineation of the Greek borders

- September 11/23, 1828: Kapodistrias, as Governor of Greece, sent a confidential Memorandum to the three Powers, protesting against the very limited borders of the new state, which he foresaw would be proposed by their representatives. He currently avoided raising the issue of independence.[7]

- November 1828: As the British Foreign Secretary, Aberdeen[8] (who succeeded George Canning after his death) recommended the first London Protocol be signed on 4/16 November with unfavorable terms for Greece: only the Peloponnese and the Cyclades were granted to Greece, a fact that provoked the strongest reaction of Kapodistrias.[9]

- March 1829: Disputes among the three Powers and the exploitation of their competition by Kapodistrias led to new negotiations at the London Conference and the signing of the second Protocol of London. With this Protocol of March 10/22 1829, it was determined to propose to the Ottomans the following:

- a. Border line at the height of Ambracian Gulf – Pagasetic Gulf and inclusion of the island of Evia and the Cyclades in the new state

- b. Sovereignty of the Sublime Porte in the Greek state with an annual tax of 1,500,000 kuruş to the Sultan.

- c. Hereditary ruler of Greece, a Christian one, foreign to the royal families of the three powers, who would be elected "by the consent of the three Courts and the Ottoman Porte".[10]

Russian-Turkish War (1828-1829) and Treaty of Adrianople

The Russian-Turkish War, was a series of twelve conflicts between the Russian Empire and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as well as the later additions France and the British Empire allying with Russia. After the ninth war ended with the defeat of Turkey in 1829, Russia forced Turkey to sign the Treaty of Adrianople, also known as the Treaty of Edirne (September 14, 1829).[11] It also had to accept the following in Article 10 of this treaty.[12] which ended with the defeat of Turkey, Russia forced it to sign the (September 14, 1829) and accept (with Article 10):[12][13]

a. The Treaty of London (6 July 1827), which was to cease hostilities as Greece revolted against rule under the Ottoman Empire. Its base arrangement was for Greece to be made a dependency of the Ottoman Empire and would pay tribute to reflect that. But later additions were made that stated Turkey had one month to accept it and if the Sultan refuse armistice the allies would use force.

b. The Protocol of March 1829, an earlier creation of the London Protocol (1830). It defined the borderline of the new Greek state alongside the Ambracian Gulf,[12][14] including the Peloponnese and Continental Greece.[15] Greece would be made into a separate state but recognise the Sultan's right to rule and pay annual tribute.

The Treaty of Adrianople also stated that the Ottoman Empire would have suzerain rule over the Danube states of Moldova and Wallachia. But also permitted Russia to take control of the towns of Anape and Poti in Caucasus and Russian traders who were in Turkey were placed under the jurisdiction of the Russian Ambassador.

Another change of English politics and the proposal of Independence

Once the Russian-Turkish War had ended, in which Russia won against Turkey of the Ottoman Empire, Russia sought to resolve Greece's wish to become a sovereign nation. Russia forced the Sultan to agree to grant autonomy to Greece and accept to terms regarding trade in the Eastern Mediterranean that were favourable to Russia such as the Russian Ambassador maintaining authority on their own merchants in Turkey and access to the Caucasus towns. Britain, who was involved in helping the other powers liberate Greece, had their own terms as well. The purpose of the British policy was then to create an independent Greek state that would close the roads to Russia in the Aegean and at the same time reduce Russian influence in the newly formed Greek state. At the same time, however, they sought to limit the borders, especially in Western Greece, so that there would be a safe distance between the new state and the Ionian Islands, which were then under British occupation.[16] The Greek Senate asked the allies that the northern border be changed to include Mount Oxas but the allies responded that this was not possible.[17] Thus, a new round of negotiations were commenced, which resulted in the Protocol of Independence (22 January / 3 February 1830), also known as the London Protocol. This protocol was accepted by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.[12]

Participants

The plenipotentiaries of England, France and Russia (Aberdeen, Montmorency-Laval, Leuven) participated in the London negotiations and signed the Protocol of Independence, while representatives of the Greeks and Turks were absent.

All three countries aimed to increase their influence in the newly formed state while limiting the influence of their opponents.

As for Kapodistrias, it was agreed to exclude him from the negotiations due to the British suspicion of him (they considered that he was inciting a revolution in the Ionian Islands).[18] Since the Powers did not even inform him about the course of the negotiations, he warned them that he would not accept unfavorable terms for Greece and insisted on his country's right to express itself at the Conference.[19]

As for the Sultan, he had agreed to sign everything that would be decided at the London conference for the implementation of peace and the end of the war.[20][21]

Signing of the protocol

In the 11 articles of the Protocol,[22][23] an independent Greek state is solemnly recognized with a restriction of the borders on the line of Acheloos-Sperchios. Crete and Samos were not adjudged to Greece, but only Euboea, the Cyclades and the Sporades. It was only Evia, the Cyclades and the Sporades that were adjudged to Greece but not Crete and Samos. With a second protocol, on the same day, Leopold was elected as the "Ruler Sovereign of Greece”[24] and a loan was granted for the maintenance of the army that he would bring with him.[25] The Great Powers demanded that Greece respect the life and property of Muslims in Greek territory and withdraw Greek troops from the areas outside its borderline.

With the protocol of February 3, the war ended and the Greek state was recognized in the international community. The recognition of the independence of Greece by the three Powers and Turkey is a critical turning point in Modern Greek history.

However, these decisions would not be final in terms of borders and the person and title of sovereign. The final settlement of the Greek Issue would occur later with the international acts of 1832.

Kapodistrias's reactions and actions to improve the northern borders

On March 27 / April 8, 1830, ambassadors from Russia, Britain and France notified Greece and the Ottoman Empire of the Protocol.[17] The Sultan was forced to accept the independence of Greece. Ioannis Kapodistrias was once the Foreign Minister for Russia and was elected as president of Greece, arriving in 1828.[26] He agreed with the condition that the Turks evacuate the islands of Attica and Euboea.[27] He also demanded the presence of foreign legislators and the provision of means to deal with the refugee problem that would be caused by the evacuation of the areas outside the borders by the Greek population. At the same time he informed Leopold, who was made king of Greece, about his claims.[28]

He also asked Leopold to embrace Eastern Orthodoxy, grant political rights to the Greeks, and work to expand the borders in order to include Acarnania, Crete, Samos, and Psara.[29]

Leopold, however, met with the refusal of the British government. A fact that led him to resign (9/21 May 1830) with the argument that he did not want to impose on the Greeks the unfavourable decisions of foreigners[28][30] but also for personal reasons.[28]

Kapodistrias’s internal opposition accepted the terms of the Protocol with relative satisfaction, accusing Kapodistrias of restricting borders like what Britain and Russia aimed to do.[31]

While ruling Greece, Kapodistrias made attempts to establish central governance over Greece. He also organised tax authorities, sorted the judiciary, introduced a quarantine system to deal with typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery infections and brought the cultivation and consumption of potatoes into the country. Though his government became increasingly unpopular and was assassinated in 1831.[26]

After the Protocol of Independence – Final regulation of the borders – Greece as a Kingdom

Leopold’s resignation in conjunction with Kapodistrias’s postponement policy led to a new Conference in July 1831 proposing to Turkey the extension of the Ambracian Gulf - Pagasetic Gulf line. Turkey was forced to accept the terms and a new protocol was finally signed (14/26 September 1831). Unfortunately, Kapodistrias was assassinated a few days later (September 27 / October 9, 1831), without being able to see the positive results of his policy.[32] He was killed by Konstantis and Georgios of the Mavromichalis family after Kapodistrias had ordered the imprisonment of Petrobey Mavromichalis on the front steps of the church of Saint Spyridon. After the assassination of Kapodistrias,[33] The three powers Russia, Britain and France with the protocol of 1/13 February 1832 and the Treaty of 25 April / 7 May in the same year that Prince Otto of the House of Wittelsbatch from Bavaria would be made King of Greece after the resignation of Leopold.[34][26] The Sultan agreed, after tough negotiations, with the signing of the Treaty of Constantinople on 9/21 July 1832 which provided for the independence of Greece and the enlarged Pagasetic Gulf - Ambracian Gulf border.[35]Prince Otto, newly crowned, arrived with a Regency Council in Greece in 1833 who ruled alongside the prince until he reached majority.[26]

See also

References

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 575.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 313.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 371.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 407.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 512.

- ^ "Άμπερντην (Aberdeen), Τζωρτζ Χάμιλτον Γκόρντον, λόρδος (1784 - 1860) - Εκδοτική Αθηνών Α.Ε." www.greekencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 513–514.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 519.

- ^ "TREATY OF ADRIANOPLE, BEING A TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN THE EMPEROR OF RUSSIA AND THE EMPEROR OF THE OTTOMANS". TREATY OF ADRIANOPLE, BEING A TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN THE EMPEROR OF RUSSIA AND THE EMPEROR OF THE OTTOMANS. 14 September 1829. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d "GREECE LIBERATED RECOGNITION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR RELATIONS". International Treaties and Protocols - GREECE LIBERATED. 2021–2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ The Revolution of 21 Dimitris Fotiadis N. Votsi Athens pp. 155-156

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 535–536.

- ^ Anderson, Rufus (1830). Observations Upon the Peloponnesus and Greek Islands, Made in 1829. Greece: Crocker and Brewster. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Sadraddinova, Gulnara (13 October 2020). "Establishment of the Greek state (1830)". Baku State University – via Grani.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 141.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 165.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 536.

- ^ Dimitris Fotiadis, The Revolution of 21, N. Votsi Publications Athens 1977, p. 182

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Dimitris Fotiadis, The Revolution of 21, N. Votsi Publications Athens 1977, p. 184

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Hatzis, Aristides (2019). "A Political History of Modern Greece, 1821-2018". Encyclopaedia of Law and Economics – via Academia.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 542.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 173.

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 561–562.

- ^ "The Assassination of Ioannis Kapodistrias". Greece Is. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Παραίτηση του πρίγκηπα Λεοπόλδου". greece2021.gr. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 576–577.

Bibliography

- Issues of modern and contemporary history from the sources - OEDB 1991, Chapter 6

- Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K., eds. (1975). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΒ΄: Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση (1821 - 1832) [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XII: The Greek Revolution (1821 - 1832)] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. ISBN 978-960-213-108-4.

- Dionysios Kokkinos, The Greek Revolution, volumes I-VI, 5th edition, Melissa, Athens 1967-1969

- D.S. Konstantopoulos, Diplomatic History, vol. I, Thessaloniki 1975

- Loukos, Christos (1988). The Opposition against the Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias. Athens: 1821-1831 Historical Library-Foundation.

- Dimitris Fotiadis , The Revolution of '21, volume IV, 2nd Edition, Publisher Nikos Votsis

External links

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from May 2022

- 1830 in London

- 1830 treaties

- 1830 in the United Kingdom

- Diplomacy during the Greek War of Independence

- Greece–United Kingdom relations

- Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- Treaties of the Bourbon Restoration

- Treaties of the Russian Empire

- February 1830 events

- Ioannis Kapodistrias