Erté

Erté | |

|---|---|

Erté in front of his works at the Sonnabend Gallery, New York City, 1970 | |

| Born | Romain Petrovich de Tirtoff[1] 23 November 1892 |

| Died | 21 April 1990 (aged 97) |

| Nationality | Russian, French |

| Known for | visual arts |

| Notable work | Symphony in Black (1920s) |

| Movement | Art Deco |

| Partner | Prince Nicholas Ourousoff |

Romain de Tirtoff (23 November 1892 – 21 April 1990), known by the pseudonym Erté (from the French pronunciation of his initials: [ɛʁte]), was a Russian-born French artist and designer. He was a 20th-century artist and designer in an array of fields, including fashion, jewellery, graphic arts, costume, and set design for film, theatre, and opera, and interior decor.

Early life

[edit]Tirtoff was born Roman Petrovich Tyrtov (Роман Петрович Тыртов) in Saint Petersburg, to a distinguished family with roots tracing back to 1548, to a Tatar khan named Tyrt.[2] His father, Pyotr Ivanovich Tyrtov, served as an admiral in the Russian Fleet.

Early in life Erte became interested in a career in the theater or dance. But eventually, as he remembered years later, I came to the conclusion that I could live without dancing but could not give up my passion for painting and design.[3]

Career

[edit]

Demoiselle à la balancelle is one of Erté's first sculptures, if not the first; it was made in 1907 at the age of 15 years while he studied in Paris. This work is less precise than his other sculptures, but still Art Nouveau. Erté considered this work so minor and uninteresting that it does not appear in his official biography, but the cartouche on the back indicates 'ERTE PARIS 1907', in a triangle.

In 1910–12, Romain moved to Paris to pursue a career as a designer. In Paris he lived with Prince Nicolas Ouroussoff (December 17, 1879 – April 8, 1933) until the prince's death in 1933.[3][4][5] The decision to move to Paris was made despite strong objections from his father, who wanted Romain to continue the family tradition and become a naval officer. Romain assumed his pseudonym to avoid upsetting his family. He worked for Paul Poiret from 1913 to 1914. In 1915, he secured his first substantial contract with Harper's Bazaar magazine, and thus launched an illustrious career that included designing costumes and stage sets. During this time, Erte designed costumes for Mata Hari.[6] Between 1915 and 1937, Erté designed over 200 covers for Harper's Bazaar, and his illustrations would also appear in such publications as Illustrated London News, Cosmopolitan, Ladies' Home Journal, and Vogue.[7]

Harper's Bazar February 1922.

Erté is perhaps most famous for his elegant fashion designs which capture the art deco period in which he worked. One of his earliest successes was designing apparel for the French dancer Gaby Deslys who died in 1920. His delicate figures and sophisticated, glamorous designs are instantly recognisable, and his ideas and art still influence fashion into the 21st century. His costumes, programme designs, and sets were featured in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1923, many productions of the Folies Bergère, Bal Tabarin, Théâtre Fémina, Le Lido,[8] and George White's Scandals.[9] On Broadway, the celebrated French chanteuse Irène Bordoni wore Erté's designs.

featuring Erté as costume designer.

In 1925, Louis B. Mayer brought him to Hollywood to design sets and costumes for the silent film Paris. There were many script problems, so Erté was given other assignments to keep him busy. Hence, he designed for such films as Ben-Hur, The Mystic, Time, The Comedian, and Dance Madness. In 1920 he designed the set and costumes for the film The Restless Sex starring Marion Davies and financed by William Randolph Hearst.

By far, his best-known image is Symphony in Black, depicting a somewhat stylized, tall, slender woman draped in black holding a thin black dog on a leash. The influential image has been reproduced and copied countless times.[10]

Erté continued working throughout his life, designing revues, ballets, and operas. He had a major rejuvenation and much lauded interest in his career during the 1960s with the Art Deco revival. He branched out into the realm of limited edition prints, bronzes, and wearable art.[11]

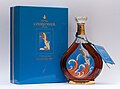

Two years before his death, Erté created seven limited edition bottle designs for Courvoisier to show the different stages of the cognac-making process, from distillation to maturation.[12] In 2008, the eighth and final set of the remaining Erte-designed Courvoisier bottles, containing Grande Champagne cognac dating back to 1892, was released and sold for $10,000 apiece.

His work may be found in the collections of several well-known museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); as well, a sizable collection of work by Erté can be found at Museum 1999 in Tokyo.

-

Erté evening dress in beaded lamé, exhibited in the Rijksmuseum

-

Erté teaches Ira Reines about the art of sculpting

Writings

[edit]- Erté (Romain de Tirtoff) by Erté; Roland Barthes. Parma : F. M. Ricci, 1970.

- Erté Fashions. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1972.

- Things I Remember: An Autobiography, Quadrangle / The New York Times Book Co., 1975, ISBN 0-8129-0575-X.

- Designs by Erté : fashion drawings and illustrations from "Harper's bazar" by Erté; Stella Blum. New York : Dover Publications, 1976.

- Erté at ninety : the complete graphics by Erté; Marshall Lee; Jack Solomon. London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1982, ISBN 9780297781707.

- Erté : sculpture by Erté; Alastair Duncan; Pascale Millière; Lee Boltin; Studio f28. Paris : Albin Michel, 1986.

- Erté: My Life / My Art: An Autobiography. New York: E P Dutton, 1989.

See also

[edit]- Dudnikov v. Chalk & Vermilion Fine Arts, Inc.: A U.S. court case over copyrights of Erté's works

References

[edit]- ^ "ERTÉ (1892-1990)". Artprice.com.

- ^ Aleksandr Vasilʹev, Beauty in Exile: The Artists, Models, and Nobility who Fled the Russian Revolution and Influenced the World of Fashion, Harry N. Abrams (2000), p. 33

- ^ a b "22 Russians Who We Won't Let Vladimir Putin Forget Were Gay". www.advocate.com. 2013-08-06. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ Who's who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II. Psychology Press. 2002. p. 180. ISBN 9780415159838. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry (2020-10-07). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-15888-5.

- ^ Times, Flora Lewis Special to The New York (December 19, 1976). "Erté Recalls the Glamour of His Art (Published 1976)". The New York Times.

- ^ Riding, Alan. "Erte, a Master of Fashion, Stage and Art Deco Design, Is Dead at 97". The New York Times 22 April 1990, accessed 26 November 2009

- ^ Erté (26 February 1979). Erté's Theatrical Costumes in Full Color. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486238135 – via Google Books.

- ^ Meg (10 January 2010). "My Postcard Collection: Erte".

- ^ Ðandy ©, Ŧhe ₵oincidental (17 November 2010). "Ŧhe ₵oincidental Ðandy: The Prolific Art, Illustrations & Designs of Erté".

- ^ "Purple Dragon's Erté Page". 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010.

- ^ "Our Heritage". ("Our Heritage | Courvoisier UK". Archived from the original on 2014-09-10. Retrieved 2014-09-09.) (accessed 16 September 2014)

External links

[edit]- "Erte, a Master of Fashion, Stage and Art Deco Design, Is Dead at 97" (obituary), The New York Times, 22 April 1990

- Erté at IMDb

- Erté site (Russian)

- Erte.com

- Erté fashion drawings

- Erté Page at the Wayback Machine (archived February 5, 2010)

- Ten Dreams Galleries