North China Craton

The North China Craton, located in northeast China, Inner Mongolia, the Yellow Sea, and North Korea, is a continental crustal block with one of Earth's most complete and complex record of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic processes[1]. Craton means a piece of continent that is stable, buoyant and rigid[1][3][4]. Basic properties of the cratonic crust includes being thick (around 200km), relatively cold when compared to other regions and low density[1][3][4]. The North China Craton is an ancient craton, which experienced long period of stability and fitted the definition of a craton well.[1] The North China Craton later experienced destruction (decratonization), which means that this piece of continent is no longer stable[3][4].

The North China Craton was at first some discrete blocks of continents which have independent tectonic activities[5]. At Paleoproterozoic (2.5-1.8 billion years ago) the continents amalgated and interacted with the supercontinent, creating belts of metamorphic rocks[5]. The exact process of how the craton was formed is still under debate as a lot of models have been proposed. After the craton was formed, it stayed stable until the middle of Ordovician (480 million years ago)[4]. The craton was then destroyed in the Eastern Block and entered period of instability. The rocks formed in the Archean and Paleoprterozoic period (4.6-1.6 billion years ago) was significantly overprinted. Apart from recording tectonic activities, the craton also contains important mineral resources, like iron and rare earth elements, and evolutionary evidences, which is in the sedimentary records.

Tectonic setting

The North China Craton covers approximately 1,500,000 km2 in area[6] and its boundaries are defined by the Central Asian Orogenic Belt to the north, the Qilianshan Orogen to the west, Qinling Dabie Orogen to the south and Su-Lu Orogen to the east.[2] Interncontinental orogen Yan Shan belt ranges from east to west in the northern part of the craton.[1]

The North China Craton consists of two blocks, the Western Block and the Eastern Block, separated by the 100-300 km wide Trans North China Orogen,[2] which is also called Central Orogenic Belt[1] or Jinyu Belt.[7] The Eastern Block covers area including southern Anshan-Benxi, eastern Hebei, southern Jilin, northern Liaoning, Miyun-Chengdu, western Shandong. It is very unstable since craton destruction started in the Phanerozoic. The Eastern Block is defined by high heat flow, thin lithosphere and a lot of earthquakes.[1] It experienced a number of magnitude 8+ earthquakes, claiming millions of lives.[1] The thin mantle root, which is the lowest part of lithosphere, is the reason for the instability.[1] The thinning of the mantle root caused the craton to destabilize, weakening the seismogenic layer, which then allow earthquakes to happen in the crust.[1] The Eastern Block might once have a thick mantle root, as shown by xenolith evidence, but it might have been removed in the Mesozoic.[1] The Western Block is located in Helanshan-Qianlishan, Daqing-Ulashan, Guyang-Wuchuan, Sheerteng and Jining[1]. It is stable because of the thick mantle root[1]. Little internal deformation occurred since Precambrian time.[1]

Geology

The rocks in the North China craton consist of Precambrian (4.6 billion years ago to 541 million years ago) basement rocks which are then overlain by Phanerozoic (541 million years ago till present) sedimentary rocks or igneous rocks[8]. The Phanerozoic rocks are largely not metamorphosed[8]. The Eastern Block is made up of early to late Archean (3.8-3.0 billion years ago) Tonalite-Trondhjemite-Granodiorite gneisses, granitic gneisses, some ultramafic to felsic volcanic rocks and metasediments with some granitoids which formed in some tectonic events 2.5 billion years ago (2.5 Ga)[8]. These are overlained by paleoproterozoic rocks which is formed in rift basins[8]. The Western Block consists of an Archean (2.6-2.5 billion years ago) basement which comprises Tonalite-Trondhjemite-Granodiorite (TTG), mafic igneous rock, and metamorphosed sedimentary rocks[8]. The Archean basement is overlained unconformably by Paleoproterozoic khondalite belts, which consist of different types of metamorphic rocks, such as graphite-bearing sillimanite garnet gneisses[8]. Geology in the Phanerozoic is complicated. Sediments were widely deposited in the Phanerozoic with various properties, for example, carbonate and coal bearing rocks were formed in late Carboniferous to early Permian (307-270 million years ago), when purple sand-bearing mudstone were formed in a lake in a shallow lake environment in Early to Middle Triassic[4]. Apart from sedimentation, there were 6 major stages of magmatism after the Phanerozoic decratonization[4]. In Jurassic to Cretaceous (100-65 million years ago), sedimentary rocks were often mixed with volcanic rocks due to volcanic activities.

Tectonic evolution

The North China Craton is one of the oldest cratons in the world[9].It experienced complex tectonic events throughout the Earth's history. The most important deformation events are the amalgamation of micro continental blocks to form the craton, and extensive metamorphism during Precambrian time (mainly 4-1.6 billion years ago)[8]. In Mesozoic to Cenozoic time(146-2.6 million years ago), the Precambrian basement rocks were extensively reworked or reactivated[8]. The tectonic evolution will be explained in the following sections in accordance to geological timescale.

Precambrian Tectonics (4.6 billion years ago to 1.6 billion years ago)

Precambrian Tectonics of the North China Craton is complicated. Different scholars have proposed different models to explain the tectonics of the Craton. The two most important schools of thought come from Kusky (2003[13], 2007[1], 2010[12]) and Zhao (2000[14][8], 2005[2], 2012[5]). The major difference in their model is the interpretation of the 2 most significant Precambrian metamorphic events, occurring 2.5 billion years ago and 1.8 billion years ago respectively, in the North China Craton. Kusky argued that the metamorphic event happened in 2.5 billion years ago correspond to the amalgamation of the Craton from their ancient blocks[1][13][12], while Zhao[2][5][8][14] is convinced that the later event is responsible for the amalgamation.

Kusky's Model --- The 2.5Ga Craton Amalgamation Model

Kusky's model proposed a sequence of events that is in-line with the microblocks amalgamating 2.5 billion years ago[13][15]. First, in the Archean time (4.6-2.5 billion years ago), lithosphere of the craton started to develop[13][15]. Some ancient micro-blocks amalgamated to form the Eastern and Western Blocks 3.8-2.7 billion years ago[13][15]. The formation time of the blocks is determined based on the age of the rocks found in the craton[13][15]. Most rocks in the craton were formed at around 2.7 billion years ago, with some small outcrop found to have formed 3.8 billion years ago[13][15]. Then, the Eastern Block underwent deformation, namely rifting at the Western Edge of the block 2.7-2.5 billion years ago[12]. Evidence for a rift system are found in the Central Orogenic Belt and they are dated 2.7 billion years old[13]. The evidence includes ophiolite and remnants of a rift system[13][15].

Collision and amalgamation started to occur in Paleoproterozoic time (2.5-1.6 billion years ago)[13][15] . 2.5-2.3 billion years ago, the Eastern and Western Blocks collided and amalgamated, forming the North China Craton with the Central Orogenic Belt in between[1][12]. The boundary of the Central Orogenic Belt is defined by Archean geology which is 1600km from west Liaoning to west of Henan province[13]. Kusky proposed that the tectonic setting of the amalgamation is an island arc, where a westward dipping subduction zone was formed[13][15]. The 2 blocks then combined through a westward subduction of the Eastern Block[13]. The timing of the collision event is determined based on the age of crystallisation of the igneous rocks in the region and the age of metamorphism in the Central Orogenic Belt[13]. Kusky also believes that the collision happened right after the rifting event, as seen from examples from orogens in other part of the world, deformation events tend to happen closely with each other in terms of timing[13]. After the amalgamation of the North China Craton, Inner Mongolia–Northern Hebei Orogen in the Western Block was formed when an arc terrane collided with the northern margin of the craton 2.3 billion years ago[13]. The arc terrane was formed in an ocean developed during post collisional extension in the amalgamation event 2.5 billion years ago[13].

Apart from the deformation event in a local scale, the craton also interacted and deformed in a regional scale[13][15]. It interacted with the Columbia Supercontinent after its formation[12]. The northern margin of the whole craton collided with another continent during the formation of Columbia Supercontinent 1.92-1.85 billion years ago[12][13]. Lastly, the tectonic setting of the craton became extensional, and therefore started to break out of the Columbia Supercontinent 1.8 billion years ago[12].

Zhao's Model --- The 1.85Ga Craton Amalgamation Model

Zhao proposed another model suggesting the amalgamation of the Eastern and Western Blocks occurred at 1.85 billion years ago instead[8][14][16][17]. The Archean time (4.6-2.5 billion years ago) was a period of crustal growth[8][14][16][17]. 3.8-2.7 billion years ago was a time of major crustal growth[8][14][16][17].

Continents started to grow in volume globally in the period, so did the North China Craton[2][5]. Pre-Neoarchean (4.6-2.8 billion years ago) rocks are just a small portion of the basement rocks, but zircon as old as 4.1 billion years old is found in the craton[2][5]. He suggests that the Neoarchean (2.8-2.5 billion years ago) crust of the North China Craton, which accounts for 85% of the Permian basement was formed in two distinct periods, 2.8-2.7 billion years ago, and 2.6-2.5 billion years ago, based on zircon age data[2][5]. Zhao suggested a pluton model to explain the formation of metamorphic rocks 2.5 billion years ago[2][5]. Neoarchean (2.8-2.5 Ma) mantle upwelled and heated up the upper mantle and lower crust, resulting in metamorphism[8].

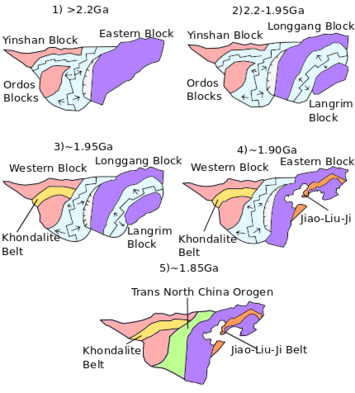

In the Paleoprterozoic time (2.5-1.6 billion years ago), the North China Craton amalgamated in three steps, with the final amalgamation took place 1.85 billion years ago[5][8]. Based on the metamorphic ages in the Trans North China Orogen, the assembly and the formation process of the North China Craton is determined[5][8]. Zhao proposed that the North China Craton was formed from 4 blocks, the Yinshain Block, the Ordos Block, the Longgang Block and the Langrim Block[5][8]. First, the Yinshan and Ordos Block collided and formed the Western Block, creating the Khondalite Belt 1.95 billion years ago[5][8]. For the Eastern Block, there was a rifting event at the Jiao-Liao-Ji Belt, which separated the Longgang Block and the Langrim Block with an ocean before the block was formed 2.1-1.9 billion years ago[5][8]. A rifting system is proposed because of how the rocks were metamorphosed in the belt and symmetrical rocks are found on both side of the Belt[5][8]. Around 1.9 billion years ago, the rift system at the Jiao-Liao- Ji Belt switched to a subductional and collisional system[5][8]. The Longgang Block and the Langrim Block then combined, forming the Eastern Block[5][8]. 1.85 billion years ago, the Eastern and Western Blocks collided to form the Trans North China Orogen in an eastward subduction system, with probably an ocean between the 2 blocks subducted[2][5][8][14].

Zhao also proposed model about the interaction of the North China Craton with the Columbia Supercontinent[17][18]. He thinks that the craton's formation event 1.85 billion years ago is part of the formation process of the Columbia Supercontinent[17][18]. The craton also recorded outward accretion event of the Columbia Supercontinent after it was formed[17][18]. The Xiong'er Volcanic Belt located in the Southern Margin of the craton recorded the accretion event of the Supercontinent in terms of a subduction zone[18]. The North China Craton breaks away from the Supercontinent 1.6-1.2 billion years ago via a rift system called Zhaertai Bayan Obo rift zone where mafic sills found is an evident of such event[18].

| Time | The 2.5Ga Amalgamation Model (Kusky) | The 1.8Ga Amalgamation Model (Zhao) |

|---|---|---|

| 3.8-2.7Ga | Ancient micro blocks amalgamated to form the Western and Eastern Block[13] | Crust grew and formed, with plutons upwell in the region, causing extensive metamorphism[2][5][8][14] |

| 2.7-2.5Ga | Eastern Block deformation (rifting in the western edge)[12] | |

| 2.5-2.3Ga | The Western and Eastern Block collided, and formed the N-S trending Central Orogenic Belt between where the 2 blocks are amalgamated[1][12] | |

| 2.3Ga | Arc Terrane collision to for Inner Mongolia- Northern Hebei Orogen in the North of the Craton[13] | |

| 2.2-1.9Ga | Rifting and collision of the Eastern Block along the Jiao-Liao-Ji Belt[5][8] | |

| 1.95Ga | Northern margin collided with continents in the Columbia Supercontinent [12][13] | Yinshan and Ordos Block collided and formed the Western Block and the Khondalite Belt[5][8] |

| 1.85Ga | Collision of the Eastern and Western Blocks leading to their amalgamation and the formation of Trans North China Orogen[5][8] | |

| 1.8Ga | The tectonic setting of the craton became extensional where the craton broke out from Columbia Supercontinent [12][13] |

Kusky and Zhao's arguments against the other model

Kusky and Zhao proposed argument against each other's model. Kusky argued that the 1.8 billion years ago metamorphic events found by Zhao to prove the amalgamation event is just the overprint of the collision event with the Columbia Supercontinent 1.85 billion years ago[12]. The collision event with the Columbia Supercontinent also replaced lithosphere with new mantle, which somehow would affect the dating[12]. Another thing is that the metamorphic rocks found in the 1.8 billion years ago is not confined to the Central Orogenic Belt (or Trans North China Orogenic Belt)[12]. It is found in the Western Block too, indicating the metamorphic events is a craton-wide event[12]. On the other hand, Zhao argued that based on the lithological evident, for example metamorphic age, from the western and eastern side of the craton, they must had formed in a different setting then the central part in 2.6-2.5 billion years ago[5]. Therefore, they would have been separated at that time[5]. The pluton upwelling can explain the metamorphic event 2.5 billion years ago[5]. Zhao also argued that the other group did not provide enough isotopic evidence for their metamorphic data[5]. As for the point Kusky proposed that deformation events should follow tight with each other rather than staying still for 700 million years, Zhao argued that there are a lot of orogens in the world that would stay still for a long period of time[5].

Other Models (Zhai's 7 Blocks Model, Faure and Trap 3 Blocks Model, Santosh Double Subduction Model)

Apart from the models Kusky and Zhao proposed, there are some other models available to explain the tectonic evolution of the North China Craton. One of the models is proposed by Zhai[19][9][20]. He agrees with the time frame of deformational events occurred in the North China Craton proposed by Kusky[19]. He also thinks that at around 2.9-2.7 billion years ago, the continent grew, 2.5 billion years ago the continental blocks amalgamated, and at around 2.0-1.8 billion years ago the craton deformed because of its activity with the Columbia Supercontinent[19]. The mechanism behind these tectonic events he proposed is rift and subduction system, which is quite similar to the two models mentioned above[19]. There is a major difference of his theory with the above-mentioned models though. He proposed that the North China Craton, instead of just simply amalgamated from the Eastern and Western Blocks, it was amalgamated from 7 ancient blocks[19][9][20]. They find that the high-grade metamorphic rocks, which is a good indicator of amalgamation events, is found all over the craton, not just restricted to the Trans North China Orogen (or the Central Orogenic Belt)i[19][9][20]. He then proposed that there must be more blocks that amalgamated in order to explain the belts of high grade metamorphic rocks, which must have been formed in a strong deformation event that can create high pressure and high temperature environment.[19][9][20].

Faure and Trap proposed another model based on the dating evidence and structural evidence they found[21][22][23]. They used Ar-Ar and U-Pb dating and structural evidences including cleavages, lineation and dip and strike data to analyse the precambrian history of the craton[21][22][23]. The timing of final amalgamation in their model is in-line with the timing proposed by Zhao, also at around 1.8-1.9 billion years ago, but they proposed another significant time of deformation, 2.1 billion years ago[21][22][23]. The division of micro-blocks deviated from Zhao's model[21][22][23]. Faure and Trap identified 3 ancient continental blocks, the Western and Eastern block same as Zhao's model, and Fuping block, replacing the Trans North China Orogen in Zhao's model[21][22][23]. The 3 blocks were separated by 2 oceans in between, the Zanhuang Ocean, and the Lüliang Ocean[21][22][23]. They further proposed the sequence and timing of the events occurred[21][22][23]. At 2.1 billion years ago, the Zanhuang Ocean closed with the Eastern Block and Fuping Block amalgamated through Taihangshan Suture[21][22][23]. At 1.9-1.8 billion years ago, the Lüliang Ocean closed and the Eastern and Western Blocks finally amalgamated[21][22][23].

Santosh proposed a model for how the continental blocks amalgamated so rapidly, providing a better picture of the mechanism of Cratonization of the North China Craton[11]. For the time frame of the deformational events, he in general agrees with Zhao's model based on metamorphic data[11]. He provides a new idea to explain the subduction direction of the plates during amalgamation, where the 2.5Ga Craton amalgamation model suggested westward subduction, and the 1.85Ga Craton amalgamation model suggested eastern subduction[11]. He did an extensive seismic mapping over the craton, making use of P-waves and S-waves[11]. He discovered traces of the subducted plate in the mantle, which indicated the possible direction of subduction of the ancient plate[11]. He finds that the Yinshan block (part of the Western Block) and the Yanliao block (part of the Eastern Block) is subducted towards the centre around the Ordos Block (part of the Western Block)[11]. The yinshan block is subducted eastward towards the Yanliao block[11]. The Yinshan block is further subducted to the south to the Ordos block[11]. The Ordos Block was therefore encountering double subduction, facilitating the amalgamation of different blocks of the craton, and it's interaction with the Columbia Supercontinent[11].

Phanerozoic History (541 million years ago- Present)

The North China Craton remained stable for a long period after the craton was amalgamated[1][4]. There were thick sediments deposited from Neoproterozoic (1000 to 541 million years ago)[1][4]. The flat lying Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks recorded animal extinction and evolutionary changes[24][4]. The centre of the craton stayed stable until mid Ordovician (467-458 million years ago) time, where xenoliths of older lithosphere started to be found in kimberlite dykes[4]. Since then, the North China Craton entered period of craton destruction, meaning that the craton was no longer a stable platform[1][4]. Most scientist defined destruction of craton as thinning of lithosphere, therefore, the losing the rigidity and stability of crust[1][4][25]. There was large scale lithosphere thinning event took place especially in the Eastern Block of the craton, resulting in large scale deformation and earthquakes in the region. Gravity Gradient showed that the Eastern Block is significantly thinner even at present day[1][26]. The mechanism and timing of the destruction of the craton is still under debate. Scientists proposed four important deformation events that could possibly lead to or contributed to craton destruction, namely subduction and closure of Paleo-Asian Ocean in Carboniferous to Jurassic (324-236 million years ago)[1][4], late Triassic collision of the Yangtze Craton and North China Craton (240-210 million years ago)[26][27][28][29][30][31][32], Jurassic subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate (200-100 million years ago)[25][33][34], and Cretaceous collapse of orogens (130-120 million years ago)[1][4][35][36][37][38]. As for the destabilisation mechanism, 4 models could be generalised. They are the subduction model[1][25][29][34][26][27], the extension model[4][30][35][38], the magma underplating mode[36]l[37][39][40][41] and the lithospheric folding model[29]. The events and models are explained below.

Craton destruction time and event

There were several major tectonic events occurring in the Phanerozoic, especially in the margins of the Eastern Block. Some of them were hypothesised to have caused the destruction of the craton.

- Carboniferous to Middle Jurassic (324-236 million years ago) --- Subduction and closure of Paleo-Asian Ocean[1][4]

- Subduction zones were located in the northern margin where continents grew through accretion [1][4]. Solonker suture was resulted and Palaeoasian ocean was therefore closed [1][4].

- There were 2 phases of magma, one occurred 324- 270 million years ago, while another occurred 262-236 million years ago[1][4]. Rocks such as syncollisional granites, metamorphic core complexes, granitoids were produced with magma from partial melts of the precambrian rocks[1][4].

- Since marine sediments deposition is found in most part of the craton, except for the northern part, it can be concluded that the craton was still relatively stable in this deformation event[4].

- Late Triassic (240-210 million years ago) --- Assembly of the North China Craton and the Yang Tze Craton [1][4]

- Suture between the North China Craton and the Yang Tze Craton was caused by deep subduction and collision setting, creating Qinling-Dabie Orogen[1][4][29]. This is supported by mineral evidence for example high pressure diamonds, eclogites and felsic gneisses[1][29].

- Magmatism was prevalent in the eastern side, and the magma formed in this period were relatively young[1][4]. Magmatism was largely caused by the collision between 2 cratons[1][4].

- Terrane accretion, continent- continent collision and extrusion in the area caused various stage of metamorphisms[1].

- Evidence from various isotopic dating (e.g. zircon U-Pb dating)[27][28][29], and composition analysis[27] showed that the lithosphere of the Yang Tze Craton was below the North China Craton in some part of the Eastern Block, and that the magma sample was young relative to the period they were formed[1][4][27][28][29]. This shows that the old lower lithosphere was extensively replaced, hence thinned[1][4][27][28][29]. This period is therefore proposed to be the time when the craton destruction occurred[1][4][27][28][29].

- Jurassic (200-100 million years ago) --- Subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate [1][4]

- Pacific Plate was subducted westward as the ocean basin to the north of the craton was closed. This was most probably an active continental margin setting[1][4][25][33][34].

- Tan Lu fault is located in Eastern side of the craton[42]. The time of its formation is debatable. Some argued that was formed in Triassic and some said Cretaceous[42]. The fault stretches 1000km to probably Russia[42]. It was probably caused by either collision with south china craton or oblique convergence with Pacific and Asia Plate[1][42].

- Scientists studied the chemical composition of the rocks to check on their origin and process of formation[25], and also studied the mantle structure[33]. It shows that the lower lithosphere in this period was newly injected[25][33]. The new material followed the NNE trend[25][33], which they concluded that subduction of the Pacific Plate caused the removal of old lithosphere and hence thinned the craton[25][33].

- Cretaceous (130-120 million years ago) --- Collapse of Orogen [1][4]

- This is a period where the mode of tectonic switched from contraction to extension[1][4]. This resulted in the collapse of the orogen formed in Jurassic to Cretaceous[1][4]. The orogenic belt and plateau (Hubei collisional plateau and Yanshan belt) started to collapse and formed metamorphic core complexes with normal faults[4][1].

- Under the influence of extensional stress field, basins, for example, Bohai Bay Basin, were formed[43].

- Magmatism was prevalent, and the isotopic studies showed that the mantle composition changed from enriched to depleted[39][36][35][34][33][4]. Evidence is from hafnium (Hf) isotope analysis[35][44][45][46][47], xenoliths zircon studies[36][39], and analysis of the metamorphic rocks[39].

Causes of Craton destruction

The causes of the craton destruction event, hence the thinning of the Eastern Block lithosphere, are complicated. Four models can be generalised from the different mechanisms proposed by scientists.

- Subduction Model

- This model explained subduction as the main cause of the craton destruction. It is a very popular model.

- Subduction of oceanic plate subducts water inside the lithosphere.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28] As the fluid encounters high temperature and pressure when being subducted, the fluid is released.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28] The release of fluids inside the lithosphere would weaken the crust and mantle as fluids would lower the melting point of rocks.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28]

- Subduction also causes the thickening of crust on the over-riding plate.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28] Once the over-thickened crust collapses, the lithosphere would be thinned.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28]

- Subduction causes the formation of eclogite because rocks are placed in the high temperature and pressure zone, for example, the subducted plate becomes deeply buried.[1][25][29][34][26][27] It would therefore cause slab break-off, slab rollback, and thinned the lithosphere.[1][25][29][34][26][27][28]

- Subduction was widely occurring in the Phanerozoic, including subduction and closure of Paleo-Asian Ocean in Carboniferous to Middle Jurassic, subduction of the Yang Tze Craton under the North China Craton in Late Triassic,[27][26][34][28] and subduction of Paleo-Pacific Plate in the Jurassic and the Cretaceous[1][25] as mentioned in the previous part. The subduction model can therefore be used to explain the proposed craton destruction event in different periods.

This is a diagram showing how lithosphere can be thinned by retreating subduction. The yellow star shows where the thinned lithosphere is. The lithosphere thinned because the subducting plate roll back faster then the over-riding plate could migrate forward[35]. As a result, the over-riding plate stretch its lithosphere to catch up with the roll back, which resulted in lithospheric thinning[35]. Modified from Zhu, 2011[35].

- Extension Model

- There are 2 types of lithospheric extension, retreating subduction and collapse of orogens.[4][30][35][38] Both of them have been used to explain lithospheric thinning occurred in the North China Craton.[30][38][4][35]

- Retreating subduction system means that the subducting plate moves backward faster then the over-riding plate moves forward.[38][4][35] The over-riding plate spreads to fill the gap.[38][4][35] With the same volume of lithosphere but being spread to a larger area, the over-riding plate is thinned.[38][4][35] This could be applied to different subduction events in Phanerozoic.[38][4][35] For example, Zhu proposes that the subduction of Paleo-Pacific Ocean was a retreating subduction system, that caused the lithospheric thinning in the Cretaceous.[4][35][38]

- Collapse of orogen introduces a series of normal faults (e.g. bookshelf faulting) and thinned the lithosphere.[30] Collapse of orogens is very common in the Cretaceous.[30]

- Magma Underplating Model

- This models implies that the young hot magma is placed very close to the crust.[36]l[37][39][40][41] The heat then melts and thins the lithosphere and causes upwelling of young asthenosphere.[36][37][39][40][41]

- Magmatism was prevalent throughout the Phanerozoic due to the extensive deformation events.[36]l[39][37][40][41] This model can therefore be used to explain lithospheric thinning in different period of time.[36][39][37][40][41]

This is a diagram showing how the lithosphere can be thinned through folding in map and cross section. Folding occurs when the Yang Tze Craton and the North China Craton collided[29]. Week points and dense elcogites were developed in the lower crust[29] . They are later fragmented and sinked because of convection of asthenosphere[29]. Edited from Zhang, 2011[29].

- Asthosphere Folding Model

- This model is specifically proposed for how the Yang Tze Craton and the North China Craton collided and thinned the lithosphere.[29]

- The collision of the 2 cratons first thickened the crust by folding[29]. Eclogite formed in the lower crust, which made the lower crust denser.[29] New shear zones also developed in the lower crust.[29]

- The asthenosphere convected and seeped into weak points developed in the lower crust shear zones.[29] The heavy lower crust was then fragmented and sinked into the lithosphere.[29] The lithosphere of the North China Craton was then thinned.[29]

Biostratigraphy

The North China Craton is very important in terms of understanding biostratigraphy and evolution[24][48]. In Cambrian and Ordovician time, the units of limestone and carbonate kept a good record of biostratigraphy and therefore they are important for studying evolution and mass extinction.[24][48] The North China platform was formed in early Palaeozoic.[24][48] It had been relatively stable during Cambrian and the limestone units are therefore deposited with relatively few interruptions.[24][48] The limestone units were deposited in underwater environment in Cambrian.[24][48] It was bounded by faults and belts for example Tanlu fault.[24][48] The Cambrian and Ordovician carbonate sedimentary units can be defined by six formations: Liguan, Zhushadong, Mantou, Zhangxia, Gushan, Chaomidian.[24][48] Different trilobite samples can be retrieved in different strata, forming biozones. For example, lackwelderia tenuilimbata (a type of trilobite) zone in Gushan formation.[24][48] The trilobite biozones can be useful to correlate and identify events in different places, like identifying unconformity sequences from a missing biozones or correlates events happening in a neighbouring block (like Tarim block).[24][48]

The carbonate sequence can also be of evolutionary significance because it indicates extinction events like the biomeres in the Cambrian.[49] Biomeres are small extinction events defined by the migration of a group of trilobite, family Olenidae, which had lived in deep sea environment.[49] Olenidae trilobites migrated to shallow sea regions while the other trilobite groups and families died out in certain time periods.[49] This is speculated to be because of a change in ocean conditions, either a drop in ocean temperature, or a drop in oxygen concentration.[49] They affected the circulation and living environment for marine species.[49] The shallow marine environment would change dramatically, resembling a deep sea environment.[49] The deep sea species would thrive, while the other species died out. The trilobite fossils actually records important natural selection processes.[49] The carbonate sequence containing the trilobite fossils hence important to record paleoenvironment and evolution.[49]

Mineral resources in The North China Craton

The North China Craton contains abundant mineral resources which are very important economically. With the complex tectonic activities in The North China Craton, the ore deposits are also very rich. Deposition of ore is affected by atmospheric and hydrosphere interaction and the evolution from primitive tectonics to modern plate tectonics.[50] Ore formation is related to supercontinent fragmentation and assembly.[50] For example, Cu and Pb deposited in sedimentary rocks indicated rifting and therefore fragmentation of a continent; Cu, Volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposits (VMS Ore deposits) and orogenic Au deposits indicated subduction and convergent tectonics, meaning almagation of continents.[50] Therefore, the formation of a certain type of ore is restricted to a specific period and the minerals are formed in relation with tectonic events.[50] Below the ore deposits are explained based on the period they were formed.

Mineral deposits

Late Neoarchean (2.8-2.5 billion years ago)

All deposits in this period are found in greenstone belts, which is a belt full of metamorphic rocks. This is consistent with the active tectonic activity in the Neoarchean.[2][50]

Banded Iron Formation (BIFs) belong to granulite facies and are widely distributed in the metamorphosed units. The age of the ore is defined by isotopic analysis of hafnium dating[51]. They are interlayered with volcanic-sedimentary rocks[50]. They can also occur as some other features: disembered layers, lenses and boudin[50]. All the iron found are in oxide form, rarely in silicate or carbonate form[50]. By analysing their oxygen isotope composition, it is suggested that the iron was deposited in an environment of weakly oxidized shallow sea environment[50][51]. There are 4 regions where extensive irons are found: Anshan in northeast China, eastern Hebei, Wutai and Xuchang-Huoqiu[50]. The North China Craton BIF formation contained the most important source of iron in China. It consists of more than 60-80% of the nations iron reserves[50].

Copper- Zinc (Cu-Zn) deposits were deposited in Hongtoushan greenstone belt, which was located in the northeastern part of The North China Craton.[50] They are typical VMS deposits and was formed under rift environment.[50] The formation of the Cu-Zn deposits might not be under modern tectonics, so the formation process might be different from modern rift system.[50]

Neoarchean greenstone belt gold deposits are located in Sandaogou (northeastern side of The North China Craton).[50][52] The greenstone belt type gold deposits are not very commonly found in the craton now because most of them were reworked in the Mesozoic, so they appeared to be in some other form.[50] However, from other cratonic examples in the world, the greenstone belt gold deposits should be abundant in the first place.[50]

Paleoproterozoic (2.5-2.6 billion years ago)

Ultra high temperature metamorphic rocks found in the Paleoproterozoic period indicate the start of modern tectonics.[50][53] Great oxygenation events (GOE) also occurred in this period and it marked the start of a shift from an oxygen poor to an oxygen rich environments.[50][53] There are two types of minerals commonly found from this period.[50][53] They are copper-lead zinc deposits and magnesite – boron deposits.

Copper-Lead-Zinc (Cu-Pb-Zn) deposits were deposited in collisional setting mobile belts, which were in a rift and subduction system.[53] Copper deposits are found in the Zhongtiaoshan area of Shanxi province.[50][53] The Khondalite sequence, which are high temperature metamorphic rocks, and graphite are often found together with the ore deposits.[50] There are a few types of ore deposits found and each of them correspond to a different formation environment.[50] Cu-Pb-An[clarification needed] formed in metamorphosed VMS deposits, Cu-Mo deposits formed in accreted arc complexes, while copper-cobalt Cu-Co deposits formed in an intrusive environment.[50][53]

Magnesite – Boron deposits were formed in sedimentary sequences under rift related shallow sea lagoon setting.[50]. It was a response to the great oxidation event as seen from its isotopic content.[50] In the Jiaoliao mobile belt, the GOE changed the isotopic ratio of 13C and 18O as the rock underwent recrystallization and mass exchange.[50] The ore also allows people to further understand the Global Oxidation Event system, for example, showing the exact atmospheric chemical change during that period.[50]

Mesoproterozoic (1.6-1.0 billion years ago)

A Rare-earth element-iron-lead-zinc (REE-Fe-Pb-Zn) system was formed from extensional rifting with upwelling of mantle, and therefore magma fractionation.[54][50] There were multiple rifting events causing the deposition of iron minerals and the rare earth element occurrence was closely related to the iron and carbonatite dykes.[54][50] The rare earth element system occurs in an alternating volcanic and sedimentary succession.[54][50] Apart from REE, LREE (Light Rare Earth Elements) are also found in carbonatite dykes.[54][50] Rare earth elements have important industrial and political implications in China.[54][50] China is close to monopolising the export of rare earth elements in the whole world.[54][50] Even the US relies heavily on rare earth elements imported from China,[54][50] while rare earth elements are absolutely essential in technologies.[55][56] Rare earth elements can make very good permanent magnets, and are therefore irreplaceable for the production of electrical appliances and technologies, for example, televisions, phones, wind turbines and lasers.[55][56]

Palaeozoic (541-350 million years ago)

A copper-Molybdenum (Cu-Mo) system originated in both the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (North) and the Qinling Orogenic Belt (South).[50]

The Central Asian Orgenic belt ore deposits occurred in arc complexes.[50] They formed from the closure of Paleo-Asian ocean.[50] The subduction generated copper and molybdenum Cu-Mo mineralization in the lithosphere block margins.[50][57][58] Duobaoshan Cu and Bainaimiao Cu-Mo deposits are found in granodiorite.[50][57] Tonghugou deposits occur with the copper ore chalcopyrite.[50] North China hosted a large reserve of molybdenum with more than 70 ore bodies found in the Northern margin of the craton.[50]

Mineral deposits in southern margin of The North China Craton are next to Qinling orogenic belt.[50][57] Some deposits were formed during the amalgamation of North and South China blocks.[50] A rifting-subduction-collision processes in Danfeng suture zone generated VMS deposits (Cu-Pb-Zn) in the arc area and a marginal fault basin[50][57].

During the opening of Paleo-Qinling oceans in this period, nickel-copper deposits formed with peridotite gabbro bodies and the ore can be found in Luonan.[50][57]

Mesozoic (251-145 million years ago)

Gold (Au) deposits in the Mesozoic are very abundant[50][59]. The formation environment of the gold includes intercontinental mineralization, craton destruction and mantle replacement.[50] The origin of the gold is from Precambrian basement rocks of the Jiaodong Complex and underlying mantle which underwent high grade metamorphism when intruded with Mesozoic granitoids.[50][59] The largest cluster of gold deposits in China is found in Jiaodong peninsula (east shandong).[50][59] The area yielded one forth of the country's gold production but consisted only of 0.2% of the area of China.[50] The three sub-clusters of gold deposits in northern China are Linglong, Yantai, Kunyushan respectively.[50]

Diamond production

China has been producing diamonds for over 40 years in the North China Craton[60]. At first diamonds were produced from alluvial deposits but later on technology improved and the diamonds are now produced from kimberlitic sources.[60] There are two main diamond mines in China, the China Diamond Corps' 701 Changma Mine in Shandong province and the Wafangdian Mine in Liaoning Province.[60] The first one operated for 34 years and produced 90000 carats of diamonds per year.[60] The second one launched with 60000 carats per annum and stopped service in 2002.[60].

The diamonds in the North China Craton came from archean lithosphere which was around 200km thick and it allowed the diamondiferous kimberlite pipes and dikes to be emplaced (occuring between 450-480Ma and Tertiary age)[60]. Ordivician aged Kimberlites could tranverse the archean mantle in orogenesis.[60] Uplift events caused the kimberlite to be exposed.[60] The two mines occur along narrow and discontinuous dikes around the Tan Lu fault.[60] Porphyritic kimberlites often occur with a matrix of other material, for example, serpentinized olivine and phlogopite or biotite, and breccia fragments.[60] The occurrence of diamonds with different materials caused a difference in diamond grade, diamond size distribution and quality in a particular mine.[60] For example, the diamonds from 701 mine are worth $40/carat, while the diamonds from Wafangdian Mine are worth $125/carate.[60]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo Kusky, T. M.; Windley, B. F.; Zhai, M.-G. (2007). "Tectonic evolution of the North China Block: from orogen to craton to orogen". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 280 (1): 1–34. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.280....1K. doi:10.1144/sp280.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Zhao, Guochun; Sun, Min; Wilde, Simon A.; Sanzhong, Li (2005). "Late Archean to Paleoproterozoic evolution of the North China Craton: key issues revisited". Precambrian Research. 136 (2): 177–202. Bibcode:2005PreR..136..177Z. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2004.10.002.

- ^ a b c Jordan, Thomas H. (1975-07-01). "The continental tectosphere". Reviews of Geophysics. 13 (3): 1–12. Bibcode:1975RvGSP..13....1J. doi:10.1029/rg013i003p00001. ISSN 1944-9208.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Zhu, Ri-Xiang; Yang, Jin-Hui; Wu, Fu-Yuan (2012). "Timing of destruction of the North China Craton". Lithos. 149: 51–60. Bibcode:2012Litho.149...51Z. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2012.05.013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Zhao, Guochun; Zhai, Mingguo (2013). "Lithotectonic elements of Precambrian basement in the North China Craton: Review and tectonic implications". Gondwana Research. 23 (4): 1207–1240. Bibcode:2013GondR..23.1207Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.08.016.

- ^ He, Chuansong; Dong, Shuwen; Santosh, M.; Li, Qiusheng; Chen, Xuanhua (2015-01-01). "Destruction of the North China Craton: a perspective based on receiver function analysis". Geological Journal. 50 (1): 93–103. doi:10.1002/gj.2530. ISSN 1099-1034.

- ^ M.G. Zhai, P. Peng (2017). "Paleoproterozoic events in North China Craton". Acta Petrologica Sinica. 23: 2665–2682.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Zhao, Guochun; Wilde, Simon A.; Cawood, Peter A.; Sun, Min (2011). "Archean blocks and their boundaries in the North China Craton: lithological, geochemical, structural and P–T path constraints and tectonic evolution". Precambrian Research. 107 (1–2): 45–73. Bibcode:2001PreR..107...45Z. doi:10.1016/s0301-9268(00)00154-6.

- ^ a b c d e Zhai, Ming-Guo; Santosh, M.; Zhang, Lianchang (2011). "Precambrian geology and tectonic evolution of the North China Craton". Gondwana Research. 20 (1): 1–5. Bibcode:2011GondR..20....1Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.04.004.

- ^ Zhao, Guochun; Li, Sanzhong; Sun, Min; Wilde, Simon A. (2011-09-01). "Assembly, accretion, and break-up of the Palaeo-Mesoproterozoic Columbia supercontinent: record in the North China Craton revisited". International Geology Review. 53 (11–12): 1331–1356. Bibcode:2011IGRv...53.1331Z. doi:10.1080/00206814.2010.527631. ISSN 0020-6814.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Santosh, M. (2010). "Assembling North China Craton within the Columbia supercontinent: The role of double-sided subduction". Precambrian Research. 178 (1–4): 149–167. Bibcode:2010PreR..178..149S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2010.02.003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Kusky, Timothy M. (2011). "Geophysical and geological tests of tectonic models of the North China Craton". Gondwana Research. 20 (1): 26–35. Bibcode:2011GondR..20...26K. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.01.004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Kusky, Timothy M.; Li, Jianghai (2003). "Paleoproterozoic tectonic evolution of the North China Craton". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 22 (4): 383–397. Bibcode:2003JAESc..22..383K. doi:10.1016/s1367-9120(03)00071-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhao, Guochun; Cawood, Peter A.; Wilde, Simon A.; Sun, Min; Lu, Liangzhao (2000). "Metamorphism of basement rocks in the Central Zone of the North China Craton: implications for Paleoproterozoic tectonic evolution". Precambrian Research. 103 (1–2): 55–88. Bibcode:2000PreR..103...55Z. doi:10.1016/s0301-9268(00)00076-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kusky, T.M.; Polat, A.; Windley, B.F.; Burke, K.C.; Dewey, J.F.; Kidd, W.S.F.; Maruyama, S.; Wang, J.P.; Deng, H. (2016). "Insights into the tectonic evolution of the North China Craton through comparative tectonic analysis: A record of outward growth of Precambrian continents". Earth-Science Reviews. 162: 387–432. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.09.002.

- ^ a b c (Geologist), Zhao, Guochun (2013). Precambrian evolution of the North China Craton. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 9780124072275. OCLC 864383254.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Zhao, Guochun; Cawood, Peter A.; Li, Sanzhong; Wilde, Simon A.; Sun, Min; Zhang, Jian; He, Yanhong; Yin, Changqing (2012). "Amalgamation of the North China Craton: Key issues and discussion". Precambrian Research. 222–223: 55–76. Bibcode:2012PreR..222...55Z. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2012.09.016.

- ^ a b c d e Zhao, Guochun; Sun, Min; Wilde, Simon A.; Li, Sanzhong (2003). "Assembly, Accretion and Breakup of the Paleo-Mesoproterozoic Columbia Supercontinent: Records in the North China Craton". Gondwana Research. 6 (3): 417–434. Bibcode:2003GondR...6..417Z. doi:10.1016/s1342-937x(05)70996-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhai, Ming-Guo; Santosh, M. (2011). "The early Precambrian odyssey of the North China Craton: A synoptic overview". Gondwana Research. 20 (1): 6–25. Bibcode:2011GondR..20....6Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.02.005.

- ^ a b c d Zhai, M (2003). "Palaeoproterozoic tectonic history of the North China craton: a review". Precambrian Research. 122 (1–4): 183–199. Bibcode:2003PreR..122..183Z. doi:10.1016/s0301-9268(02)00211-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Trap, Pierre; Faure, Michel; Lin, Wei; Augier, Romain; Fouassier, Antoine (2011). "Syn-collisional channel flow and exhumation of Paleoproterozoic high pressure rocks in the Trans-North China Orogen: The critical role of partial-melting and orogenic bending". Gondwana Research. 20 (2–3): 498–515. Bibcode:2011GondR..20..498T. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.02.013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Trap, P.; Faure, M.; Lin, W.; Bruguier, O.; Monié, P. (2008). "Contrasted tectonic styles for the Paleoproterozoic evolution of the North China Craton. Evidence for a ∼2.1Ga thermal and tectonic event in the Fuping Massif". Journal of Structural Geology. 30 (9): 1109–1125. Bibcode:2008JSG....30.1109T. doi:10.1016/j.jsg.2008.05.001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Trap, P.; Faure, M.; Lin, W.; Monié, P. (2007). "Late Paleoproterozoic (1900–1800Ma) nappe stacking and polyphase deformation in the Hengshan–Wutaishan area: Implications for the understanding of the Trans-North-China Belt, North China Craton". Precambrian Research. 156 (1–2): 85–106. Bibcode:2007PreR..156...85T. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.03.001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chough, Sung Kwun; Lee, Hyun Suk; Woo, Jusun; Chen, Jitao; Choi, Duck K.; Lee, Seung-bae; Kang, Imseong; Park, Tae-yoon; Han, Zuozhen (2010-09-01). "Cambrian stratigraphy of the North China Platform: revisiting principal sections in Shandong Province, China". Geosciences Journal. 14 (3): 235–268. Bibcode:2010GescJ..14..235C. doi:10.1007/s12303-010-0029-x. ISSN 1226-4806.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Gao, Shan; Rudnick, Roberta L.; Xu, Wen-Liang; Yuan, Hong-Lin; Liu, Yong-Sheng; Walker, Richard J.; Puchtel, Igor S.; Liu, Xiaomin; Huang, Hua (2008). "Recycling deep cratonic lithosphere and generation of intraplate magmatism in the North China Craton". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 270 (1–2): 41–53. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.270...41G. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Windley, B. F.; Maruyama, S.; Xiao, W. J. (2010-12-01). "Delamination/thinning of sub-continental lithospheric mantle under Eastern China: The role of water and multiple subduction". American Journal of Science. 310 (10): 1250–1293. Bibcode:2010AmJS..310.1250W. doi:10.2475/10.2010.03. ISSN 0002-9599.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Yang, De-Bin; Xu, Wen-Liang; Wang, Qing-Hai; Pei, Fu-Ping (2010). "Chronology and geochemistry of Mesozoic granitoids in the Bengbu area, central China: Constraints on the tectonic evolution of the eastern North China Craton". Lithos. 114 (1–2): 200–216. Bibcode:2010Litho.114..200Y. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2009.08.009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zheng, J.P.; Griffin, W.L.; Ma, Q.; O'Reilly, S.Y.; Xiong, Q.; Tang, H.Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Yu, C.M.; Su, Y.P. (2011). "Accretion and reworking beneath the North China Craton". Lithos. 149: 61–78. Bibcode:2012Litho.149...61Z. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2012.04.025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Zhang, Kai-Jun (2011). "Destruction of the North China Craton: Lithosphere folding-induced removal of lithospheric mantle?". Journal of Geodynamics. 53: 8–17. Bibcode:2012JGeo...53....8Z. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2011.07.005.

- ^ a b c d e f Yang, Jin-Hui; O'Reilly, Suzanne; Walker, Richard J.; Griffin, William; Wu, Fu-Yuan; Zhang, Ming; Pearson, Norman (2010). "Diachronous decratonization of the Sino-Korean craton: Geochemistry of mantle xenoliths from North Korea". Geology. 38 (9): 799–802. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..799Y. doi:10.1130/g30944.1.

- ^ Yang, Jin-Hui; Wu, Fu-Yuan; Wilde, Simon A.; Chen, Fukun; Liu, Xiao-Ming; Xie, Lie-Wen (2008-02-01). "Petrogenesis of an Alkali Syenite–Granite–Rhyolite Suite in the Yanshan Fold and Thrust Belt, Eastern North China Craton: Geochronological, Geochemical and Nd–Sr–Hf Isotopic Evidence for Lithospheric Thinning". Journal of Petrology. 49 (2): 315–351. Bibcode:2007JPet...49..315Y. doi:10.1093/petrology/egm083. ISSN 0022-3530.

- ^ Yang, Jin-Hui; Wu, Fu-Yuan; Wilde, Simon A.; Belousova, Elena; Griffin, William L. (2008). "Mesozoic decratonization of the North China block". Geology. 36 (6): 467. Bibcode:2008Geo....36..467Y. doi:10.1130/g24518a.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wu, Fu-yuan; Walker, Richard J.; Ren, Xiang-wen; Sun, De-you; Zhou, Xin-hua (2005). "Osmium isotopic constraints on the age of lithospheric mantle beneath northeastern China". Chemical Geology. 196 (1–4): 107–129. Bibcode:2003ChGeo.196..107W. doi:10.1016/s0009-2541(02)00409-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tang, Yan-Jie; Zhang, Hong-Fu; Santosh, M.; Ying, Ji-Feng (2013). "Differential destruction of the North China Craton: A tectonic perspective". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 78: 71–82. Bibcode:2013JAESc..78...71T. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.11.047.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Zhu, Guang; Jiang, Dazhi; Zhang, Bilong; Chen, Yin (2011). "Destruction of the eastern North China Craton in a backarc setting: Evidence from crustal deformation kinematics". Gondwana Research. 22 (1): 86–103. Bibcode:2012GondR..22...86Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.08.005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Liu, Yongsheng; Gao, Shan; Yuan, Hongling; Zhou, Lian; Liu, Xiaoming; Wang, Xuance; Hu, Zhaochu; Wang, Linsen (2004). "U–Pb zircon ages and Nd, Sr, and Pb isotopes of lower crustal xenoliths from North China Craton: insights on evolution of lower continental crust". Chemical Geology. 211 (1–2): 87–109. Bibcode:2004ChGeo.211...87L. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.06.023.

- ^ a b c d e f He, Lijuan (2014). "Thermal regime of the North China Craton: Implications for craton destruction". Earth-Science Reviews. 140: 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.10.011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zhu, Guang; Chen, Yin; Jiang, Dazhi; Lin, Shaoze (2015). "Rapid change from compression to extension in the North China Craton during the Early Cretaceous: Evidence from the Yunmengshan metamorphic core complex". Tectonophysics. 656: 91–110. Bibcode:2015Tectp.656...91Z. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2015.06.009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zhai, Mingguo; Fan, Qicheng; Zhang, Hongfu; Sui, Jianli; Shao, Ji'an (2007). "Lower crustal processes leading to Mesozoic lithospheric thinning beneath eastern North China: Underplating, replacement and delamination". Lithos. 96 (1–2): 36–54. Bibcode:2007Litho..96...36Z. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2006.09.016.

- ^ a b c d e Zhang, Hong-Fu; Ying, Ji-Feng; Tang, Yan-Jie; Li, Xian-Hua; Feng, Chuang; Santosh, M. (2010). "Phanerozoic reactivation of the Archean North China Craton through episodic magmatism: Evidence from zircon U–Pb geochronology and Hf isotopes from the Liaodong Peninsula". Gondwana Research. 19 (2): 446–459. Bibcode:2011GondR..19..446Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.09.002.

- ^ a b c d e Zhang, Hong-Fu; Zhu, Ri-Xiang; Santosh, M.; Ying, Ji-Feng; Su, Ben-Xun; Hu, Yan (2011). "Episodic widespread magma underplating beneath the North China Craton in the Phanerozoic: Implications for craton destruction". Gondwana Research. 23 (1): 95–107. Bibcode:2013GondR..23...95Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.12.006.

- ^ a b c d Xiao, Yan; Zhang, Hong-Fu; Fan, Wei-Ming; Ying, Ji-Feng; Zhang, Jin; Zhao, Xin-Miao; Su, Ben-Xun (2010). "Evolution of lithospheric mantle beneath the Tan-Lu fault zone, eastern North China Craton: Evidence from petrology and geochemistry of peridotite xenoliths". Lithos. 117 (1–4): 229–246. Bibcode:2010Litho.117..229X. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2010.02.017.

- ^ Li, S. Z.; Suo, Y. H.; Santosh, M.; Dai, L. M.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Zhao, S. J.; Jin, C. (2013-09-01). "Mesozoic to Cenozoic intracontinental deformation and dynamics of the North China Craton". Geological Journal. 48 (5): 543–560. doi:10.1002/gj.2500. ISSN 1099-1034.

- ^ Chen, B.; Jahn, B. M.; Arakawa, Y.; Zhai, M. G. (2004-12-01). "Petrogenesis of the Mesozoic intrusive complexes from the southern Taihang Orogen, North China Craton: elemental and Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic constraints". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 148 (4): 489–501. Bibcode:2004CoMP..148..489C. doi:10.1007/s00410-004-0620-0. ISSN 0010-7999.

- ^ Chen, B.; Tian, W.; Jahn, B.M.; Chen, Z.C. (2007). "Zircon SHRIMP U–Pb ages and in-situ Hf isotopic analysis for the Mesozoic intrusions in South Taihang, North China craton: Evidence for hybridization between mantle-derived magmas and crustal components". Lithos. 102 (1–2): 118–137. Bibcode:2008Litho.102..118C. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2007.06.012.

- ^ Yang, Jin-Hui; Wu, Fu-Yuan; Chung, Sun-Lin; Wilde, Simon A.; Chu, Mei-Fei; Lo, Ching-Hua; Song, Biao (2005). "Petrogenesis of Early Cretaceous intrusions in the Sulu ultrahigh-pressure orogenic belt, east China and their relationship to lithospheric thinning". Chemical Geology. 222 (3–4): 200–231. Bibcode:2005ChGeo.222..200Y. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.07.006.

- ^ Chen, B.; Chen, Z.C.; Jahn, B.M. (2009). "Origin of mafic enclaves from the Taihang Mesozoic orogen, north China craton". Lithos. 110 (1–4): 343–358. Bibcode:2009Litho.110..343C. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2009.01.015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Myrow, Paul M.; Chen, Jitao; Snyder, Zachary; Leslie, Stephen; Fike, David A.; Fanning, C. Mark; Yuan, Jinliang; Tang, Peng (2015). "Depositional history, tectonics, and provenance of the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary interval in the western margin of the North China block". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 127 (9–10): 1174–1193. Bibcode:2015GSAB..127.1174M. doi:10.1130/b31228.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Taylor, John F (2006). "History and status of the biomere concept". Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists. 32: 247–265.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd Zhai, Mingguo; Santosh, M. (2013). "Metallogeny of the North China Craton: Link with secular changes in the evolving Earth". Gondwana Research. 24 (1): 275–297. Bibcode:2013GondR..24..275Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.02.007.

- ^ a b Zhang, Xiaojing; Zhang, Lianchang; Xiang, Peng; Wan, Bo; Pirajno, Franco (2011). "Zircon U–Pb age, Hf isotopes and geochemistry of Shuichang Algoma-type banded iron-formation, North China Craton: Constraints on the ore-forming age and tectonic setting". Gondwana Research. 20 (1): 137–148. Bibcode:2011GondR..20..137Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.02.008.

- ^ Zhang, Ju-Quan; Li, Sheng-Rong; Santosh, M.; Lu, Jing; Wang, Chun-Liang (2017). "Metallogenesis of Precambrian gold deposits in the Wutai greenstone belt: Constrains on the tectonic evolution of the North China Craton". Geoscience Frontiers. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2017.08.005.

- ^ a b c d e f Deng, X.H.; Chen, Y.J.; Santosh, M.; Zhao, G.C.; Yao, J.M. (2013). "Metallogeny during continental outgrowth in the Columbia supercontinent: Isotopic characterization of the Zhaiwa Mo–Cu system in the North China Craton". Ore Geology Reviews. 51: 43–56. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2012.11.004.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yang, Kui-Feng; Fan, Hong-Rui; Santosh, M.; Hu, Fang-Fang; Wang, Kai-Yi (2011). "Mesoproterozoic carbonatitic magmatism in the Bayan Obo deposit, Inner Mongolia, North China: Constraints for the mechanism of super accumulation of rare earth elements". Ore Geology Reviews. 40 (1): 122–131. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2011.05.008.

- ^ a b Du, Xiaoyue; Graedel, T. E. (2011-12-01). "Global Rare Earth In-Use Stocks in NdFeB Permanent Magnets". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 15 (6): 836–843. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2011.00362.x. ISSN 1530-9290.

- ^ a b Rotter, Vera Susanne; Chancerel, Perrine; Ueberschaar, Maximilian (2013). Kvithyld, Anne; Meskers, Christina; Kirchain, Randolph; Krumdick, Gregory; Mishra, Brajendra; Reuter, rkus; Wang, Cong; Schlesinger, rk; Gaustad, Gabrielle (eds.). REWAS 2013. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 192–201. doi:10.1002/9781118679401.ch21. ISBN 978-1-118-67940-1.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Sheng-Rong; Santosh, M. (2013). "Metallogeny and craton destruction: Records from the North China Craton". Ore Geology Reviews. 56: 376–414. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2013.03.002.

- ^ Zhang, Lian-chang; Wu, Hua-ying; Wan, Bo; Chen, Zhi-guang (2009). "Ages and geodynamic settings of Xilamulun Mo–Cu metallogenic belt in the northern part of the North China Craton". Gondwana Research. 16 (2): 243–254. Bibcode:2009GondR..16..243Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2009.04.005.

- ^ a b c Chen, Yanjing; Guo, Guangjun; LI, Xin (1997). "Metallogenic geodynamic background of Mesozoic gold deposits in granite-greenstone terrains of North China Craton" (PDF). Science in China. 41. doi:10.1007/BF02932429.pdf (inactive 2017-11-18) – via Springer.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2017 (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Michaud, Michael (2005). "An Overview of Diamond exploration in the North China Craton". Mineral Deposit Research: Meeting the Global Challenge: 1547–1549. doi:10.1007/3-540-27946-6_394. ISBN 978-3-540-27945-7.