Mohammad Khatami

Muhammad Khatami | |

|---|---|

محمد خاتمی | |

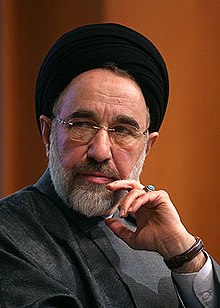

Khatami in 2007 | |

| 5th President of Iran | |

| In office 3 August 1997 – 3 August 2005 | |

| Supreme Leader | Ali Khamenei |

| Vice President | Hassan Habibi Mohammad Reza Aref |

| Preceded by | Akbar Rafsanjani |

| Succeeded by | Mahmoud Ahmadinejad |

| Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance | |

| In office 9 November 1982 – 24 May 1992 | |

| President | Ali Khamenei Akbar Rafsanjani |

| Prime Minister | Mir-Hossein Mousavi |

| Preceded by | Mir-Hossein Mousavi (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Ali Larijani |

| Member of the Parliament of Iran | |

| In office 28 May 1980 – 24 August 1982 | |

| Preceded by | Manouchehr Yazdi |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad Hosseininejad |

| Constituency | Yazd, Ardakan district |

| Majority | 40,112 (82.1%)[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 October 1943 Ardakan, Yazd Province, Pahlavi Iran |

| Political party | Association of Combatant Clerics |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Mohammad-Reza Khatami (brother) Ali Khatami (brother) Mohammad Reza Tabesh (nephew) |

| Alma mater | University of Isfahan University of Tehran |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Iranian Imperial Army[2] |

| Years of service | 1969–1971[2] |

| Rank | Second lieutenant; Financial specialist[2] |

| Unit | Tehran region 3 sustainment[2] |

Mohammad Khatami (Persian: سید محمد خاتمی, romanized: Seyd Mohammad Khātami, pronounced [mohæmˈmæde xɒːtæˈmiː] ; born 14 October 1943)[3][4][5][6] is an Iranian reformist politician who served as the fifth president of Iran from 3 August 1997 to 3 August 2005. He also served as Iran's Minister of Culture from 1982 to 1992. Later, he was critical of the government of subsequent President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[7][8][9][10]

Little known internationally before becoming president, Khatami attracted attention during his first election to the presidency when he received almost 70% of the vote.[11] Khatami had run on a platform of liberalization and reform. During his election campaign, Khatami proposed the idea of Dialogue Among Civilizations as a response to Samuel P. Huntington's 1992 theory of a Clash of Civilizations.[12] The United Nations later proclaimed the year 2001 as the Year of Dialogue Among Civilizations, on Khatami's suggestion.[13][14][15] During his two terms as president, Khatami advocated freedom of expression, tolerance and civil society, constructive diplomatic relations with other states, including those in Asia and the European Union, and an economic policy that supported a free market and foreign investment.

On 8 February 2009, Khatami announced that he would run in the 2009 presidential election[16] but withdrew on 16 March in favour of his long-time friend and adviser, former prime minister of Iran Mir-Hossein Mousavi.[17] The Iranian media are forbidden on the orders of Tehran's prosecutor from publishing pictures of Khatami, or quoting his words, on account of his support for the defeated reformist candidates in the disputed 2009 re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[18]

Early life and education

[edit]Khatami was born on 14 October 1943, in the small town of Ardakan, in Yazd Province into a sayyid family. He married Zohreh Sadeghi, the daughter of a professor of religious law, and niece of Musa al-Sadr, in 1974 (at the age of 31). The couple have two daughters and one son: Laila (born 1975), Narges (born 1980), and Emad (born 1988).

Khatami's father, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khatami, was a high-ranking cleric and the Khatib (the one who delivers the sermon for Friday prayers) in the city of Yazd in the early years of the Iranian Revolution.

Khatami's brother, Mohammad-Reza Khatami, was elected as Tehran's first member of parliament in the 6th term of parliament, during which he served as deputy speaker of the parliament. He also served as the secretary-general of Islamic Iran Participation Front (Iran's largest reformist party) for several years. Mohammad Reza is married to Zahra Eshraghi, a feminist human rights activist and granddaughter of Ruhollah Khomeini (founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran).

Khatami's other brother, Ali Khatami, a businessman with a master's degree in Industrial Engineering from Polytechnic University in Brooklyn,[19] served as the President's Chief of Staff during President Khatami's second term in office, where he kept an unusually low profile.

Khatami's eldest sister, Fatemeh Khatami, was elected as the first representative of the people of Ardakan (Khatami's hometown) in 1999 city council elections.

Mohammad Khatami is not related to Ahmad Khatami, a hardline cleric and Provisional Friday Prayer Leader of Tehran.[20][21]

Mohammad Khatami received a BA in Western philosophy at Isfahan University, but left academia while studying for a master's degree in educational sciences at Tehran University and went to Qom to complete his previous studies in Islamic sciences. He studied there for seven years and completed the courses to the highest level, Ijtihad. After that, he briefly settled in Germany to chair the Islamic Centre in Hamburg from 1978 to 1980.

Before serving as president, Khatami was a representative in the parliament from 1980 to 1982, supervisor of the Kayhan Institute, Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance (1982–1986), and then for a second term from 1989 to 24 May 1992 (when he resigned), the head of the National Library of Iran from 1992 to 1997, and a member of the Supreme Council of Cultural Revolution. He is a member and chairman of the Central Council of the Association of Combatant Clerics. Besides his native language Persian, Khatami speaks Arabic, English, and German.[22]

Presidency (1997–2005)

[edit]

Running on a reform agenda, Khatami was elected president on 23 May 1997, in what many have described as a remarkable election. Voter turnout was nearly 80%. Despite limited television airtime, most of which went to the conservative Speaker of Parliament and favored candidate Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri, Khatami received 70 percent of the vote. "Even in Qom, the center of theological training in Iran and a conservative stronghold, 70% of voters cast their ballots for Khatami."[23] He was re-elected on 8 June 2001 for a second term and stepped down on 3 August 2005 after serving his maximum two consecutive terms under the Islamic Republic's constitution.

Khatami supporters have been described as a "coalition of strange bedfellows, including traditional leftists, business leaders who wanted the state to open up the economy and allow more foreign investment, and younger voters.[23] Khatami’s ascendancy was a prelude to a dynamic reform thrust that injected hope into Iranian society, whipped up a dormant nation after eight years of war with Iraq in the 1980s and the costly post-conflict reconstruction, and incorporated terms in the political lexicon of young Iranians that were not previously embedded in the national discourse, nor did they count as priorities for the majority of the people.

The day of his election, 2 Khordad, 1376, in the Iranian calendar, is regarded as the starting date of "reforms" in Iran. His followers are therefore usually known as the "2nd of Khordad Movement".

Khatami is regarded as Iran's first reformist president, since the focus of his campaign was on the rule of law, democracy, and the inclusion of all Iranians in the political decision-making process. However, his policies of reform led to repeated clashes with the hardline and conservative Islamists in the Iranian government, who control powerful governmental organizations like the Guardian Council, whose members are appointed by the Supreme Leader.

As President, according to the Iranian political system, Khatami was outranked by the Supreme Leader. Thus, Khatami had no legal authority over key state institutions such as the armed forces, the police, the army, the revolutionary guards, the state radio and television, and the prisons. (See Politics of Iran).

Khatami presented the so-called "twin bills" to the parliament during his term in office, these two pieces of proposed legislation would have introduced small but key changes to the national election laws of Iran and also presented a clear definition of the president's power to prevent constitutional violations by state institutions. Khatami himself described the "twin bills" as the key to the progress of reforms in Iran. The bills were approved by the parliament but were eventually vetoed by the Guardian Council.

Generality

[edit]Press freedom, civil society, women’s rights, religious tolerance, dialogue and political development were concepts that constituted the core of Khatami’s ideology, who as a cleric faced immeasurable pressure on behalf of the orthodox seminarians over the changes he was advocating. He inducted his Westward charm offensive by engaging the European Union, and became the first Iranian president to travel to Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway and Spain. From the University of St Andrews in Scotland to the World Economic Forum in Davos and the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, he was frequently solicited to give talks at reputed venues to articulate the new Iranian vision and tell the world how he wanted to portray his people’s aspirations.

Economic policy

[edit]Khatami's economic policies followed the previous government's commitment to industrialization. At a macro-economic level, Khatami continued the liberal policies that Rafsanjani had embarked on in the state's first five-year economic development plan (1990–1995). On 10 April 2005, Khatami cited economic development, large-scale operations of the private sector in the country's economic arena and 6% economic growth as among the achievements of his government. He allocated $5 billion to the private sector for promoting the economy, adding that the value of contracts signed in this regard has reached $10 billion.

A year into his first term as president of Iran, Khatami acknowledged Iran's economic challenges, stating that the economy was, "chronically ill...and it will continue to be so unless there is fundamental restructuring".

For much of his first term, Khatami saw through the implementation of Iran's second five-year development plan. On 15 September 1999, Khatami presented a new five-year plan to the Majlis. Aimed at the period from 2000 to 2004, the plan called for economic reconstruction in a broader context of social and political development. The specific economic reforms included "an ambitious program to privatize several major industries ... the creation of 750,000 new jobs per year, average annual real GDP growth of six percent over the period, reduction in subsidies for basic commodities...plus a wide range of fiscal and structural reforms". Unemployment remained a major problem, with Khatami's five-year plan lagging behind in job creation. Only 300,000 new jobs were created in the first year of the plan, well short of the 750,000 that the plan called for. The 2004 World Bank report on Iran concludes that "after 24 years marked by internal post-revolutionary strife, international isolation, and deep economic volatility, Iran is slowly emerging from a long period of uncertainty and instability".[24]

At the macroeconomic level, real GDP growth rose from 2.4% in 1997 to 5.9% in 2000. Unemployment was reduced from 16.2% of the labor force to less than 14%. The consumer price index fell to less than 13% from more than 17%. Both public and private investments increased in the energy sector, the building industry, and other sectors of the country's industrial base. The country's external debt was cut from $12.1 billion to $7.9 billion, its lowest level since the Iran-Iraq cease-fire. The World Bank granted $232 million for health and sewage projects after a hiatus of about seven years. The government, for the first time since the 1979 wholesale financial nationalization, authorized the establishment of two private banks and one private insurance company. The OECD lowered the risk factor for doing business in Iran to four from six (on a scale of seven).[25]

The government's own figures put the number of people under the absolute poverty line in 2001 at 15.5% of the total population – down from 18% in 1997, and those under relative poverty at 25%, thus classifying some 40% of the population as poor. Private estimates indicate higher figures.[26]

Among 155 countries in a 2001 world survey, Iran under Khatami was 150th in terms of openness to the global economy. On the United Nations Human Development scale, Iran ranked 90th out of 162 countries, only slightly better than its previous position at 97 out of 175 countries four years earlier.[27] The overall risk of doing business in Iran improved only marginally from "D" to "C".[26][28] One of his economic strategies was on the basis of absorbing foreign and domestic capital resources for the privatization of the economy. Therefore, in 2001, the organization of privatization was established. Also the government encourages people to buy shares in private companies by providing incentives. Also Iran succeeded to convince the World Bank to approve loans totaling 432 billion dollars to the country.[29]

Foreign policy

[edit]

During Khatami's presidency, Iran's foreign policy began a process of moving from confrontation to conciliation. In Khatami's notion of foreign policy, there was no "clash of civilizations", he favored instead a "Dialogue Among Civilizations". Relations with the US remained marred by mutual suspicion and distrust, but during Khatami's two terms, Tehran increasingly made efforts to play a greater role in the Persian Gulf region and beyond.

As President, Khatami met with many influential figures including Pope John Paul II, Koichiro Matsuura, Jacques Chirac, Johannes Rau, Vladimir Putin, Abdulaziz Bouteflika, Mahathir Mohamad and Hugo Chávez. In 2003, Khatami refused to meet militant Iraqi cleric Moqtada al-Sadr.[30] However, Khatami attended Hafez al-Assad's funeral in 2000 and told new Syrian president Bashar al-Assad that "the Iranian government and people would stand by and support him".[31]

On 8 August 1998, the Taliban massacred 4,000 Shias in the town of Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. It also attacked and killed 11 Iranian diplomats with an Iranian journalist among them. The rest of the diplomats were taken hostage. Ayatollah Khamenei ordered the amassing of troops near the Iran Afghanistan border to enter Afghanistan and fight the Taliban. Over 70,000 Iranian troops were placed along the borders of Afghanistan. Khatami halted the invasion and looked to the UN for help. Soon he was placed in talks. Later Iran entered negotiations with the Taliban, the diplomats were released. Khatami and his advisers had managed to keep Iran from entering war with the Taliban.

After the 2003 earthquake in Bam, the Iranian government rebuffed Israel's offer of assistance. On 8 April 2005, Khatami sat near Iranian-born Israeli President Moshe Katsav during the funeral of Pope John Paul II because of alphabetical order. Later, Katsav shook hands and spoke with Khatami. Katsav himself is in origin an Iranian Jew, and from a part of Iran close to Khatami's home; he stated that they had spoken about their home province. That would make this incident the first official political contact between Iran and Israel since diplomatic ties were severed in 1979.

However, after he returned to Iran, Khatami was subject to harsh criticism from conservatives for having "recognised" Israel by speaking to its president. Subsequently, the country's state-run media reported that Khatami strongly denied shaking hands and chatting with Katsav.[32] In 2003, Iran approached the United States with proposals to negotiate all outstanding issues including the nuclear issue and a two-state settlement for Israel and the Palestinians.[33] In 2006, and as an ex-president, he became the highest-ranking Iranian politician to visit the United States, excluding annual diplomatic trips of chief executives to the UN headquarters in New York. He gave a speech at the Washington National Cathedral and continued his US tour by addressing Harvard University, Georgetown University and the University of Virginia.

Currency crisis

[edit]

From 1995 to 2005, Khatami's administration successfully reduced the rate of fall in the value of the Iranian rial bettering even the record of Mousavi. Nevertheless, the currency continued to fall from 2,046 to 9,005 to the U.S. dollar during his term as president.

Cultural

[edit]Khatami's moderate policies also differed sharply from those of his radical opponents, who sought stricter Islamic rule. Thus, the moderate Khatami all-inclusive and pluralistic message posed a stark contrast to the reactionary stances of the earlier decades of the revolution. He represented hope for the masses who desired change that differed in nature from what they had experienced in 1979, and yet a change that preserved Iran’s Islamic republican system. In the first years of his presidency, relative freedom of the press was formed in the country, and for the first time after the summer of 1360, some opposition forces were able to print publications or publish articles criticizing the performance of high-ranking officials. During this period, the Association of Iranian Journalists, the national union of journalists in Iran was established in October 1376 after Mohammad Khatami took office. National Library and Archive of Iran It was completed with Khatami's follow-up. and banned books were allowed to be printed as Kelidar. Bahram Beyzai, Abbas Kiarostami They did many activities during this period and the country's cinema space became more open. With a glance at this period, it can be seen that most filmmakers turned their attention to making films with social themes. Iran Music House and Music Festival of Iran's regions institutes it was founded in this period. Iran's National Orchestra founded in 1998 under the conduction of Farhad Fakhreddini.

Khatami and Iran's 2004 parliamentary election

[edit]

In February 2004, Parliament elections, the Guardian Council banned thousands of candidates, including most of the reformist members of the parliament and all the candidates of the Islamic Iran Participation Front party from running.[34] This led to a win by the conservatives of at least 70% of the seats. Approximately 60% of the eligible voting population participated in the elections.

Khatami recalled his strong opposition against holding an election his government saw as unfair and not free. He also narrated the story of his visit to the Supreme Leader, Khamenei, together with the Parliament's spokesman (considered the head of the legislature) and a list of conditions they had handed him before they could hold the elections. The list, he said, was then passed on to the Guardian Council, the legal supervisor and major obstacle to holding free and competitive elections in recent years. The members of the Guardian Council are appointed directly by the Supreme Leader and are considered to be applying his will. "But", Khatami said, "the Guardian Council kept neither the Supreme Leader's nor its own word [...] and we were faced with a situation in which we had to choose between holding the election or risking huge unrest [...] and so damaging the regime". At this point, student protesters repeatedly chanted the slogan "Jannati is the nation's enemy", referring to the chairman of the Guardian Council. Khatami replied, "If you are the representative of the nation, then we are the nation's enemy". However, after clarification by students stating that "Jannati, not Khatami", he took advantage of the opportunity to claim a high degree of freedom in Iran.[35]

When the Guardian Council announced the final list of candidates on 30 January 125 reformist members of parliament declared that they would boycott the election and resign their seats, and the Reformist interior minister declared that the election would not be held on the scheduled date, 20 February. However, Khatami then announced that the election would be held on time, and he rejected the resignations of his cabinet ministers and provincial governors. These actions paved the way for the election to be held and signaled a split between the radical and moderate wings of the reformist movement.[36]

Cultural and political image

[edit]Dialogue Among Civilizations

[edit]

Following earlier works by the philosopher Dariush Shayegan, in early 1997, during his presidential campaign, Khatami introduced the theory of Dialogue Among Civilizations as a response to Samuel P. Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations" theory. He introduced this concept in the United Nations in 1998.[12]

Consequently, on 4 November 1998 the UN adopted a resolution proclaiming the year 2001 as the United Nations' Year of Dialogue Among Civilizations, as per Khatami's suggestion.[13][14][15] Pleading for the moralization of politics, Khatami argued that "the political translation of dialogue among civilizations would consist in arguing that culture, morality, and art must prevail on politics". President Khatami's call for a dialogue among civilizations elicited a published reply from an American author, Anthony J. Dennis, who served as the originator, contributor, and editor of an historic and unprecedented collection of letters addressing all facets of Islamic-Western and U.S.–Iranian relations entitled Letters to Khatami: A Reply To The Iranian President's Call For A Dialogue Among Civilizations which was published in the U.S. by Wyndham Hall Press in July 2001.[37] To date, this book is the only published reply Khatami has ever received from the West.

Culture

[edit]Khatami believes that the modern world in which we live is such that Iranian youth are confronted with new ideas and is receptive of foreign habits. He also believes that the limitation on youth leads to separation of them from the regime and calls them into Satanic cultures. He predicted that even worse, the youth will learn and accept the MTV culture. This fact leads to secularization.[38]

Cinema

[edit]In terms of Islamic values, Mohammad Khatami encouraged film makers to include themes such as self-sacrifice, martyrdom, and revolutionary patience. When Khatami was the minister of culture, he believed that cinema was not limited to the mosque and it is necessary to pay attention to entertaining aspects of cinema and not limiting it to religious aspect.[39]

Khatami as a scholar

[edit]

Khatami's main research field is political philosophy. One of Khatami's academic mentors was Javad Tabatabaei, an Iranian political philosopher. Later on Khatami became a University lecturer at Tarbiat Modarres University, where he taught political philosophy. Khatami also published a book on political philosophy in 1999. The ground he covers is the same as that covered by Javad Tabatabaei: The Platonizing adaptation of Greek political philosophy by Farabi (died 950), its synthesis of the "eternal wisdom" of Persian statecraft by Abu'l-Hasan Amiri (died 991) and Mushkuya Razi (died 1030), the juristic theories of al-Mawardi and Ghazali, and Nizam al-Mulk's treatise on statecraft. He ends with a discussion of the revival of political philosophy in Safavid Isfahan in the second half of the 17th century.

Further, Khatami shares with Tabatabaei the idea of the "decline" of Muslim political thought beginning at the very outset, after Farabi.

Like Tabatabaei, Khatami brings in the sharply contrasting Aristotelian view of politics to highlight the shortcomings of Muslim political thought. Khatami has also lectured on the decline in Muslim political thought in terms of the transition from political philosophy to royal policy (siyasat-i shahi) and its imputation to the prevalence of "forceful domination" (taghallub) in Islamic history.[40]

In his "Letter for Tomorrow", he wrote:

This government is proud to announce that it heralded the era where the sanctity of power has been turned into the legitimacy of critique and criticism of that power, which is in the trust of the people who have been delegated with power to function as representatives through franchise. So such power, once considered Divine Grace, has now been reduced to an earthly power that can be criticized and evaluated by earthly beings. Instances show that although due to some traces of despotic mode of background we have not even been a fair critique of those in power, however, it is deemed upon the society, and the elite and the intellectuals in particular, not to remain indifferent at the dawn of democracy and allow freedom to be hijacked.

Post-presidential career

[edit]

After his presidency, Khatami founded two NGOs which he currently heads:

- International Institute for Dialogue among Cultures & Civilizations,[41] (Persian: موسسه بین المللی گفتگوی فرهنگها و تمدنها). This institute is a private (non-governmental) institute that was founded by Khatami after the end of his presidency and it is not to be confused with a center with a similar name operated by the foreign ministry of Iran. The European branch of Khatami's institute is headquartered in Geneva and has been registered as Foundation for Dialogue among Civilizations.[42]

- Baran Foundation.[43] BARAN meaning "rain" is an acronym in Persian for "Foundation for Freedom, Growth and Development of Iran" (Persian: بنیاد آزادی، رشد و آبادانی ایران – باران). This is also a private (non-governmental) institute founded by Khatami after the end of his presidency (registration announced on 9 September 2005) and a group of his former colleagues during his presidency. This institute is focused on domestic rather than international activities.

Notable events in Khatami's career after his presidency include:

- On 2 September 2005, the then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan appointed Mohammad Khatami as a member of the Alliance of Civilizations.

- On 28 September 2005, Khatami retired after 29 years of service in the government.[44]

- On 14 November 2005, Mohammad Khatami urged all religious leaders to fight for the abolishment of atomic and chemical weapons.[45][46]

- On 30 January 2006, Mohammad Khatami officially inaugurated the office of the "International Institute of Dialogue Among Civilizations", an NGO with offices in Iran and Europe that he will be heading, after his retirement from the government.[47]

- On 15 February 2006, during a press interview Mohammad Khatami announced the formal registration of the European office of his Institute for Dialogue among Civilizations in Geneva.

- On 28 February 2006, while attending a conference of the Alliance of Civilizations at Doha, Qatar, he stated that "The Holocaust is a historical fact." However, he added that Israel has "made a bad use of this historic fact with the persecution of the Palestinian people."[48]

- On 7 September 2006, during a visit to Washington, Mohammad Khatami called for dialogue between the United States and Iran.[49]

- On 24–28 January 2007, Mohammad Khatami attended the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, then British Prime Minister Tony Blair, former U.S. President Bill Clinton, then U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton, former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, then Vice President Dick Cheney, and former U.S. Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and Colin Powell were among those attending.[50] Khatami and then U.S. Senator John Kerry have expressed similar opinions and shared words with each other in the World Economic Forum in Davos.[51][52]

- In October 2009, the award committee of the Global Dialogue Prize[53] declared Khatami and Iranian cultural theorist Dariush Shayegan as joint winners of the inaugural award, "for their work in developing and promoting the concept of a 'dialogue among cultures and civilizations' as new paradigm of cultural subjectivity and as new paradigm of international relations". The Global Dialogue Prize is one of the world's most significant recognitions for research in the Humanities, honouring "excellence in research and research communication on the conditions and content of a global intercultural dialogue on values".[54] In January 2010, Mohammad Khatami stated that "he was not in the position to accept the award", and the prize was given to Dariush Shayegan alone.[55]

The Man with the Chocolate Robe

[edit]On 22 December 2005, a few months after the end of Khatami's presidency, the monthly magazine Chelcheragh, along with a group of young Iranian artists and activists, organized a ceremony in Khatami's honor. The ceremony was held on Yalda night at Tehran's Bahman Farhangsara Hall. The ceremony, titled "A Night with The Man with the Chocolate Robe" by the organizers, was widely attended by teenagers and younger adults. One of the presenters and organizers of the ceremony was Pegah Ahangarani, a popular young Iranian actress. The event did not get a lot of advance publicity, but it drew a huge amount of attention afterwards. In addition to formal reports on the event by the BBC, IRNA, and other major news agencies, googling the term "مردی با عبای شکلاتی" ("The Man with the Chocolate Robe" in Persian) shows thousands of results of mainly young Iranians' blogs mentioning the event. It was arguably the first time in the history of Iran that an event in such fashion was held in honor of a head of government. Some weblog reports of the evening described the general atmosphere of the event as "similar to a concert!", and some reported that "Khatami was treated like a pop star" among the youth and teenagers in attendance during the ceremony. Many bloggers also accused him of falling short of his promises of a safer, more democratic Iran.[56][57]

2008 International Conference on Religion in Modern World

[edit]In October 2008, Khatami organized an international conference on the position of religion in the modern world. Former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan, former Norwegian Prime Minister Kjell Magne Bondevik, former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi, former French Prime Minister Lionel Jospin, former Swiss President Joseph Deiss, former Portuguese President Jorge Sampaio, former Irish President Mary Robinson, former Sri Lankan President Chandrika Kumaratunga and former UNESCO director general Federico Mayor as well as several other scholars were among the invited speakers of the conference.[58]

The event was followed by a celebration of the historical city of Yazd, one of the most famous cities in Persian history and Khatami's birthplace. Khatami also announced that he is about to launch a television program to promote intercultural dialogue.

2009 presidential election

[edit]Khatami contemplated running in the 2009 Iranian presidential election.[59] In December 2008, 194 alumni of Sharif University of Tech wrote a letter to him and asked him to run against Ahmadinejad "to save the nation".[60] On 8 February 2009, he announced his candidacy at a meeting of pro-reform politicians.[61]

On 16 March 2009, Khatami officially announced he would drop out of the presidential race to endorse another reformist candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi who Khatami claimed would stand a better chance against Iran's conservative establishment to offer true change and reform.[62][63]

Green movement

[edit]In December 2010, following the crushing of post-election protest, Khatami was described as working as a political "insider," drawing up a "list of preconditions" to present to the government "for the reformists' participation in the upcoming parliamentary elections", that would be seen as reasonable by the Iranian public but intolerable by the government. This was seen by some (Ata'ollah Mohajerani) as "astute" and proving "the system could not take even basic steps required for living up to its own democratic conservatives" (Azadeh Moaveni). In response to the conditions, Kayhan newspaper condemned Khatami as "a spy and traitor" and called for his execution.[64]

2013 presidential election

[edit]

A few months before the presidential election which was held in June 2013, several reformist groups in Iran invited Khatami to attend in competition. The reformists also sent a letter to the Iran Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in December 2012, regarding the participation of Khatami in the upcoming presidential election. Member of the traditional-conservative Islamic Coalition Party, Asadullah Badamchyan said that in their letter, the reformists asked the Supreme Leader to supervise the allowance of Khatami to participate in the upcoming election.[65] Former mayor of Tehran, Gholamhossein Karbaschi announced: "Rafsanjani may support Khatami in the presidential election".[66]

Khatami himself said that he still waits for the positive changes in the country, and will reveal his decision when the time is suitable. On 11 June 2013, Khatami together with a council of reformists backed moderate Hassan Rouhani, in Iran's presidential vote as Mohammad Reza Aref quit the race when Khatami advised him that it "would not be wise" for him to stay in the race for the June 2013 elections.[67]

Controversy and criticism

[edit]Khatami's two terms as president were regarded by some people in the Iranian Opposition as unsuccessful or not fully successful in achieving their goals of making Iran more free and more democratic,[68] and he has been criticized by conservatives, reformers, and opposition groups for various policies and viewpoints.

In a 47-page "A Letter for Tomorrow", Khatami said his government had stood for noble principles but had made mistakes and faced obstruction by hardline elements in the clerical establishment.[68]

Electoral history

[edit]| Year | Election | Votes | % | Rank | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Parliament | 32,942 | 82.1 | 1st | Won |

| 1992 | Parliament | — | Disqualified[69] | ||

| 1997 | President | 20,078,187 | 69.6 | 1st | Won |

| 2001 | President | 1st | Won | ||

Primary sources

[edit]

Publications

[edit]Khatami has written a number of books in Persian, Arabic, and English:

Books in Persian

- Fear of the Wave (بیم موج)

- From the World of a city to the city of the World (از دنیای شهر تا شهر دنیا)

- Faith and Thought Trapped by Despotism (آیین و اندیشه در دام خودکامگی)

- Democracy (مردم سالاری)

- Dialogue Among Civilizations (گفتگوی تمدنها)

- A Letter for Tomorrow (نامه ای برای فردا)

- Islam, The Clergy, and The Islamic Revolution (اسلام، روحانیت و انقلاب اسلامی)

- Political Development, Economic Development, and Security (توسعه سیاسی، توسعه اقتصادی و امنیت)

- Women and the Youth (زنان و جوانان)

- Political Parties and the Councils (احزاب و شوراها)

- Reviving Inherent Religious Truths (احیاگر حقیقت دین)

Books in English

- Islam, Liberty and Development[70] ISBN 978-1-883058-83-8

Books in Arabic

- A Study of Religion, Islam and Time [title roughly translated from Arabic] (مطالعات في الدين والإسلام والعصر)

- City of Politics [title roughly translated from Arabic] (مدينة السياسة)

A full list of his publications is available at his official personal web site (see below).

Awards and honors

[edit]

- Gold medal from University of Athens

- The special medal of Spain's Congress of Deputies and Senate, Key to Madrid

- Honorary PhD, Moscow State Institute of International Relations

- Honorary doctorate in Philosophy from University of Moscow

- Honorary PhD degree, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- Honorary doctorate degree by the Delhi University

- Honorary doctorate from National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan

- Degree of honor in political sciences, Lebanese University

- Pakistan's highest civilian honour

- Plaque of honor and medal of distinction by the International Federation for Parent Education

- Honorary doctorate from Al-Neelain University

- Honorary doctorate of Law from University of St Andrews

- Venezuela's Order of the Liberator

See also

[edit]- 2nd of Khordad Movement

- 1997 Iranian presidential election

- 2001 Iranian presidential election

- 2009 Iranian presidential election

- 2013 Iranian presidential election

- Liberal movements within Islam

- Modern Islamic philosophy

References and notes

[edit]- ^ "Parliament members" (in Persian). Iranian Majlis. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d ایران, عصر (23 January 1392). "کارت پایان خدمت خاتمی (عکس)". fa.

- ^ Esposito, John L.; Shahin, Emad El-Din (4 October 2016). The Oxford Handbook of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063193-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "انتخابات92". Facebook. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022.

- ^ "عكس:جشن تولد خاتمی - تابناک | TABNAK".

- ^ "وزراي دولت اصلاحات چه آرايي از نمايندگان مجلس گرفتند؟".

- ^ "The Struggle for Iran". The Weekly Standard. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Iran: People Rally In Ardakan In Support Of Opposition Leader Mohammad Khatami". Payvand. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Khatami Prevented from Leaving Iran for Japan". insideIRAN. 15 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Karroubi Challenges Hardliners to Put Green Movement Leaders on Trial". PBS. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Profile: Mohammad Khatami". BBC News. 6 June 2001. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Khatami Speaks of Dialogue among Civilizations". diplomacy. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Dialogue among Civilizations". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Round Table: Dialogue among Civilizations United Nations, New York, 5 September 2000 Provisional verbatim transcription". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007.

- ^ a b Petito, Fabio (2004). "Khatami' Dialogue among Civilizations as International Political Theory" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities. 11 (3): 11–29.

- ^ "Iran's Khatami to run for office". BBC News. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ "Former Iranian president exits election race". The Irish Times. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Iran's Rouhani praises Khatami role in recent vote".

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (2001). Persian Mirrors: The Elusive Face of Iran. Simon & Schuster. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-7432-1779-9.

- ^ "Iranian Cleric: Fatwa Against Rushdie is 'Still Alive'". Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ U.S. policies on Iran defeated Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Ahmad Khatami 20 July 2007, IRNA

- ^ "Profile: Mohammad Khatami". BBC News. 6 June 2001.

- ^ a b "1997 Presidential Election". PBS. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Siddiqi, Ahmad. "SJIR: Khatami and the Search for Reform in Iran". Stanford. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ [Tahavolat, 98–138; Economic Trends, no. 23 (Tehran: Central Bank, 2000–2001); and Iran: Interim Assistance Strategy (Washington: The World Bank, April 2001).]

- ^ a b Amuzegar, Jahangir (March 2002). "Project MUSE". SAIS Review. 22 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1353/sais.2002.0001. S2CID 153845590.

- ^ UNDP, Human Development Report 2001 (New York: UNDP, 2001).

- ^ Iran Economics (Tehran), July/August 2001.

- ^ Anoushiravan Enteshami & Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconsevatives, the politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 15.

- ^ Order Out of Chaos Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Hoover Institution

- ^ Samii, Abbas William (Winter 2008). "A Stable Structure on Shifting Sands: Assessing the Hizbullah-Iran-Syria Relationship" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 62 (1): 32–53. doi:10.3751/62.1.12. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Iranian President Denies Israeli Handshake". MSNBC. 9 April 2005.

- ^ "U.S.–Iran Roadmap" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- ^ "Iran reformists' protest continues". CNN. 12 January 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "FToI: What did Khatami really say?". Free thoughts. 8 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Strategic Insights – Iranian Politics After the 2004 Parliamentary Election". CCC. June 2004. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Anthony J. Dennis, LETTERS TO KHATAMI: A Reply To The Iranian President's Call For A Dialogue Among Civilizations (Wyndham Hall Press, 2001, ISBN 1556053339).

- ^ Anoushiravan Enteshami & Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconsevatives, the politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 17.

- ^ Hamid Naficy in Farsoun andMashayekhi (1992). Islamizing film cultural in iran in political cultural in the Islamic republic. Routledge. pp. 200–205. ISBN 9781134969470.

- ^ "The Reform Movement and the Debate on Modernity and Tradition in Contemporary Iran". Archived from the original on 8 August 2003.

- ^ "International Institute for Dialogue Among Cultures and Civilizations". Dialogue. 1 September 2008. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Welcome To FDC Website" (in Persian). Dialogue Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Baran". Baran. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ "Khatami Retires". Archived from the original on 29 September 2005.

- ^ "Newsday | Long Island's & NYC's News Source | Newsday". Retrieved 15 November 2005.[dead link]

- ^ [1] Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Non-Productive Sectors Unhelpful". Archived from the original on 10 July 2007.

- ^ [2] Archived 21 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Iran's Khatami calls for US talks". BBC News. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ^ "Khatami to attend World Economic Forum in Davos". Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Khatami & Kerry: A Common Denominator". Radiojavan.com. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Kerry confirmed Khatami's remarks in his address (ISNA)". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Global Dialogue Prize". Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Iran's Khatami awarded 2009 "Global Dialogue Prize"". Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ The (copyrighted) webpages of the Global Dialogue Prize offer a brief scholarly presentation of Khatami's contributions to the concept of dialogue as paradigm of international relations, as well as a bibliography.

- ^ "Mohammad Ali Abtahi's weblog report of the evening". webneveshteha.com.

- ^ "BBC News: The Man with the Chocolate Robe". Bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "World Dignitaries Open International Conference On Religion". Bernama. 14 October 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Erdbrink, Thomas (16 December 2008). "Iran's Khatami Mulls Run for Presidency". The Washington Post. p. A15. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "بیايید و با مردم سخن بگويید (Rooz)". Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ Hafezi, Parisa (8 February 2009). "Iran's Khatami to run in June presidential election". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Former president khatami won't run for the next presidential election race". Former President Khatami's website. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Iran's Khatami won't run for president, state news agency says". CNN. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ The Smiling Cleric's Revolution, BY Moaveni, Azadeh|16 February 2011

- ^ "Reformists send a letter to Supreme Leader regarding ex-president's participation in elections". Ilna. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Rafsanjani may support Khatami in presidential election". Oana news. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Khatami, reformists back Rohani in Iran presidential vote". Reuters. 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

- ^ a b Khatami blames clerics for failure", The Guardian, 4 May 2004.

- ^ Farzin Sarabi (subscription required) (1994). "The Post-Khomeini Era in Iran: The Elections of the Fourth Islamic Majlis". Middle East Journal. 48 (1). Middle East Institute: 107. JSTOR 4328663.

The first victim of the cabinet changes, however, was Hoijatolislam Mohammad Khatami-Ardekani, culture and Islamic guidance minister. Khatami, who is a member of Ruhaniyoun and was disqualified to run for the Majlis by the Council of Guardians, was not on Rafsanjani's list of those for possible dismissal

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Khātamī, Muḥammad (1998). Islam, Liberty and Development: Mohammad Khatami, Muhammad Khatami: Books. Institute of Global Cultural Studies, Binghamton University. ISBN 188305883X.

External links

[edit]- Official website of Khatami's BARAN NGO Institute in Iran

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Khatami and the Search for Reform in Iran (Review article; Stanford University) Archived 7 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Biography in Encyclopædia Britannica

- Khatami; from the presidency of Islamic Center in Hamburg to the presidency of Islamic Republic of Iran

- CNN: Transcript of Interview with Iranian President Mohammad Khatami

- Iran's ex-leader sees new Islam

- Address of Mohammad Khatami at Annual Meeting of World Economic Forum, Davos, 21 January 2004, Chaired by Klaus Schwab, 26 min 37 sec, Video on YouTube

- Mohammad Khatami

- 1943 births

- Living people

- Government ministers of Iran

- Iranian Green Movement

- Iranian librarians

- Iranian reformists

- Iranian scholars

- 20th-century Persian-language writers

- University of Tehran alumni

- Iranian democracy activists

- Islamic democracy activists

- Muslim reformers

- People from Ardakan

- Presidents of Iran

- Iranian Shia clerics

- Association of Combatant Clerics politicians

- University of Isfahan alumni

- Candidates in the 1997 Iranian presidential election

- Candidates in the 2001 Iranian presidential election

- Members of the 1st Islamic Consultative Assembly

- Representatives of the Supreme Leader in the Keyhan Institute

- Heads of the National Library of Iran

- 20th-century Iranian politicians

- 21st-century Iranian politicians

- Iranian military chaplains

- 20th-century presidents in Asia