Tales from Topographic Oceans

| Tales from Topographic Oceans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 7 December 1973 | |||

| Recorded | Late summer and autumn, 1973 | |||

| Studio | Morgan, Willesden, London | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 81:14 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Yes chronology | ||||

| ||||

Tales from Topographic Oceans is the sixth studio album by English progressive rock band Yes, released as a double album on 7 December 1973 by Atlantic Records. It is their first studio album to feature drummer Alan White, who had replaced Bill Bruford in the previous year.

Frontman Jon Anderson devised the album's concept during the 1973 Japanese tour, when he read a footnote in Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda that describes four bodies of Hindu texts about a specific field of knowledge, collectively named shastras: the śruti, smriti, puranas, and tantras. After pitching the idea to guitarist Steve Howe, the two developed an outline of the album's themes and lyrics which led to the group's decision to produce a double album containing four side-long tracks based on each text, ranging between 18 and 21 minutes. Keyboardist Rick Wakeman was openly critical of the concept and felt unable to contribute to the music that had been written, creating friction between himself and the rest of the group.

The album received mixed reviews and became a symbol of the perceived excesses of the progressive rock genre, but earned a more positive reception in later years. It was a commercial success, becoming the first UK album to be certified gold based solely on pre-orders, and was number one in the UK for two weeks. It reached number 6 in the US, where it was certified gold in 1974 for surpassing 500,000 copies. Yes promoted the album with the largest tour since their formation, which featured an elaborate stage designed by cover artist Roger Dean, and the entire album performed live. Wakeman's increased frustrations on the tour led to his departure at its conclusion. In 2003, the album was remastered with previously unreleased tracks, and an edition with new stereo and 5.1 surround sound mixes by Steven Wilson, with additional bonus tracks, followed in 2016.

Background and writing

In March 1973, Yes were on the Japanese leg of the Close to the Edge Tour in support of their previous album Close to the Edge (1972), which was a critical and commercial success and reached the top five in the UK and the US. While in his hotel room in Tokyo, Anderson explored ideas for the band's next album, one of which involved a "large-scale composition" as the group had success with longform pieces, including the 18-minute title track from Close to the Edge. With the idea in mind Anderson found himself "caught up in a lengthy footnote" in Autobiography of a Yogi (1946) by Paramahansa Yogananda which outlines four bodies of Hindu texts, named shastras,[1] that Yogananda described as "comprehensive treatises [that cover] every aspect of religious and social life, and the fields of law, medicine, architecture, art..." that "convey profound truths under a veil of detailed symbolism".[2] Anderson "became engrossed" with the idea of a "four-part epic" concept album based on the four texts, though he later admitted that he did not fully understand what the scriptures were about.[3] He was introduced to Yogananda by King Crimson drummer and percussionist Jamie Muir at Bruford's wedding reception on 2 March 1973.[4] Anderson said of Muir: "I felt I had to learn from him. We started talking about meditation in music—not the guru type but some really heavy stuff."[3] Anderson gained further clarification of the texts from talking to Vera Stanley Alder, a mystic, painter, and author of spirituality books that had a profound influence on him.[5]

Yes moved on to Australia and the US in March and April 1973, during which Anderson pitched his idea to Howe, a prolific songwriter and arranger in the group who took an interest in the concept. In their spare time between gigs, the pair held writing sessions in their hotel rooms lit by candlelight, sharing musical and lyrical ideas. Howe recalled: "Jon would say to me, 'What have you got that's a bit like that...?' so I'd play him something and he'd go: 'that's great. Have you got anything else?' and I'd play him another tune".[6] One riff that Howe played was initially discarded, but it was later incorporated into "The Ancient (Giants Under the Sun)" as by then, the two sought for a different theme that would suit the track.[6] Howe looked back on this time as a "golden opportunity" for Anderson and himself to "explore the outer reaches of our possibilities", and avoided predicatable choruses and song structures.[7] A six-hour session in Savannah, Georgia, that ended at 7 a.m. saw Anderson and Howe complete the outline of the album's vocals, lyrics, and instrumentation, which took the form of one track based on each of the four texts. Anderson described the night as "magical [that] left both of us exhilarated for days".[8] When it came to pitching the album to the rest of the band Howe recalled some resistance, "but Jon and I did manage to sell the idea ... sometimes [we] really had to spur the guys on".[6]

"I think there was a psychological effect of, "Oh, we're doing a double album. Now we can make things twice as long, twice as boring, and twice as drawn out!"[9]

—Eddy Offord, producer

When touring finished, Yes regrouped at Manticore Studios in Fulham, London, then owned by fellow progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer, to rehearse and develop Anderson and Howe's initial ideas.[3] This resulted in four tracks, as Wakeman described: "One was about eight minutes. One was 15. One was 19 and one was 12", but the band had to decide whether to refine them to fit a single album or extend them to make a double. Howe recalled a mutual agreement to make a double album,[6][3] which Wakeman supported provided that the group could come up with strong enough music.[10] Anderson had gained confidence towards making a double from the success of Yessongs, their first live album, released as a triple album in May 1973 that contained almost 130 minutes of music.[11] Wakeman revealed an early musical concept for Tales from Topographic Oceans when Yessongs was released. It was to be an album whose parts can be interchangeable at any time depending on the audience's reaction, thus allowing the band to perform upbeat portions back to back and skip the slower sections until a later time in the piece. However, the problem was how to record such a concept on an album.[12]

The group had no material at hand, so ideas came about through improvisation, with which Wakeman disagreed; he called it "almost busking, free-form thinking" and thought parts of it resembled "avant-garde jazz rock, and I had nothing to offer".[10][13] Though he considered "Ritual (Nous sommes du soleil)" a strong track, and thought there to be some good melodies and themes throughout the album, he remained displeased with the musical "padding" that was added.[10] Squire recognised "a lot of substance" to the four tracks, but at times they lacked strength, which resulted in an album that was "too varied and too scattered".[14][9] The band took a break roughly one month into rehearsals, during which Anderson vacated to Marrakesh with his family and wrote lyrics.[5] Despite the mixed opinions, Anderson wrote in the album's liner notes that Squire, Wakeman, and White made "important contributions of their own" to the music.[15] He believed the group were "on the same page" and supported the album at the time, but later concluded that Wakeman's criticisms and subsequent departure marked the end of the "illusive harmony" that was in Yes since Fragile (1971).[16]

Album title

Phil Carson, then the London Senior Vice President of Atlantic Records, remembered that, during a dinner with Anderson and Nesuhi Ertegun, Anderson was originally going to name the album Tales from Tobographic Oceans and claimed he invented the word "tobographic", a word that summarised one of Fred Hoyle's theories of space. Ertegun informed Anderson that "tobographic" sounded like "topographic", so Anderson changed the title accordingly.[17] Wakeman jokingly nicknamed the album Tales from Toby's Graphic Go-Kart.[10]

Recording

Yes spent five months arranging, rehearsing, and recording Tales from Topographic Oceans.[15] The group were split in deciding where to record; Anderson and Wakeman wanted to retreat in the countryside while Squire and Howe preferred to stay in London, leaving White, who was indifferent, as the tie-breaking vote.[18] Anderson had thought of recording under a tent in a forest at night with electrical generators buried into the ground so they would be inaudible, but "when I suggested that, they all said, 'Jon, get a life!'"[19][1] Yes were joined by engineer and producer Eddy Offord, who had worked with the band since 1970 and mixed their sound on tour. He pushed their manager Brian Lane to record in the country, thinking "some flowers and trees" would lessen the tension that the album had created within the group,[9] but Yes were swayed to remain in London and record at Morgan Studios as it housed a 3M M79, Britain's first 24-track tape machine, which presented greater possibilities in the studio.[20][7] Despite the advantage, Squire recalled that the machine malfunctioned often.[21] Squire worked in the studio for as long as sixteen-hour days, seven days a week on the album.[22] Yes's studio time amounted to £90,000 in costs.[23]

When the band settled into Morgan Studios, Lane and Anderson decorated it to resemble a farmyard; Squire believed Lane did so as a joke on Anderson when his idea of recording in the country did not happen.[20] Anderson brought in flowers, pots of greenery, and cut out cows and sheep,[19] and Wakeman recalled white picket fences and his keyboards and amplifiers placed on stacks of hay.[20] At the time of recording, heavy metal group Black Sabbath were recording Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973) in the adjacent studio. Singer Ozzy Osbourne recalled the Yes studio also had a model cow with electronic udders and a small barn to give the room an "earthy" feel.[24] Offord said that roughly halfway through recording, "the cows were covered in graffiti and all the plants had died. That just kind of sums up that whole album".[9] At one point during the recording, Anderson wished for a bathroom sound effect on his vocals and asked lighting engineer Michael Tait to build him a three-sided plywood box with tiles for him to sing in. Despite Tait explaining how the idea would not work, he built it.[25][7] Sound engineer Nigel Luby recalled tiles falling off the box during takes.[26]

Wakeman felt increasingly disenchanted by the album during the recording stage, and spent much of his time drinking and playing darts in the studio bar.[27] He also spent time with Black Sabbath, playing the Minimoog synthesiser on their track "Sabbra Cadabra". Wakeman would not accept money for his contribution, so the band paid him in beer.[28]

In one incident during the last few days of mixing, Anderson left the studio one morning with Offord carrying the tapes. Offord placed them on-top of his car in order to find his car keys, and proceeded to drive away, forgetting about the tapes. They stopped the car to find that the tapes had slid off and fallen on the road, causing Anderson to rush back and stop an oncoming bus to save them.[6]

Songs

"Side one was the commercial or easy-listening side of Topographic Oceans, side two was a much lighter, folky side of Yes, side three was electronic mayhem turning into acoustic simplicity, and side four was us trying to drive the whole thing home on a biggie."[29]

Tales from Topographic Oceans contains four tracks, or "movements" as described by Anderson,[15] that range between 18 and 22 minutes. The lyrics were written by Anderson and Howe, and all band members are credited for composing the music. Its liner notes feature a short summary written by Anderson of how the album's concept is expressed in a musical sense.[30]

"The Revealing Science of God (Dance of the Dawn)" is based on the shruti class of Hindu scripture which Yogananda described as scriptures that are "directly heard" or "revealed", in particular the Vedas.[2] Regarding its title, Anderson said: "It's always delicate to start talking about religious things ... [the track] should have just been 'The Revealing'. But I got sort of hip." The track was originally 28 minutes in length, but six minutes were cut due to the time constraints of a vinyl.[31] Howe's guitar solos on the track, performed on a Gibson ES-345,[32] were influenced by his belief that Frank Zappa performed lengthy solos "because the audience wanted it. I was thinking at one stage, "I'll do that. They'll love it".[31] Anderson was inspired to open the track with voices that gradually build from listening to Gregorian chants. The ongoing Vietnam War at the time provided a source for its lyrics.[19] The "Young Christians see it..." section originated from an unused take from the Fragile recording sessions that was released on its 2015 reissue as "All Fighters Past".[6] White recalled the group spending around six days on mixing the track.[6] The song was 20:27 in length on original pressings, but some later pressings (also on 2003 expanded version) include an additional two minute intro.

"The Remembering (High the Memory)" relates to the smriti, literally meaning "that which is remembered". Yogananda wrote the smritis were "written down in a remote past as the world's longest epic poems", specifically the Mahabharata and Ramayana, two Indian epic poems.[2] Anderson described it as "a calm sea of music" and aimed to get the band to play "like the sea" with "rhythms, eddies, swells, and undercurrents".[31] The track includes a keyboard solo that Anderson wrote: "bring[s] alive the ebb and flow and depth of our mind's eye".[15] Anderson ranked the solo as one of Wakeman's best works.[19] Squire described his bass playing on the track, done on a fretless Guild bass, as "one of the nicest things" he has done, ranking it higher than his playing on some of the band's more popular tracks. He called it a very successful piece of musical arrangement.[31] White came up with the chord basis of an entire section of the song on the guitar, which he does not play confidently, but Anderson told him to play the part repeatedly to him until he could grasp it.[33] Howe plays a Danelectro electric sitar, lute, and acoustic guitar on the track.[34]

"The Ancient (Giants Under the Sun)" is attributed to the puranas, meaning "of ancient times", which contain eighteen "ancient" allegories.[2] "Steve's guitar", wrote Anderson, "is pivotal in sharpening reflection on the beauties and treasures of lost civilisations."[15] The lyrics contain several translations of the word "Sun" or an explanation of the Sun from various languages.[19] Howe felt the opening section amazes him to this day, thinking how the band could "go so far out".[3] He plays a steel guitar and a Spanish Ramirez acoustic guitar,[34][6] and described it as "quite Stravinsky, quite folky". To help achieve the right sound he wanted out of his guitars, Howe played several recordings by classical guitarist Julian Bream to Offord as a guide.[6] The track ends with an acoustic-based song which later became known as "Leaves of Green".

"Ritual (Nous sommes du soleil)" relates to the tantras, literally meaning "rites" or "rituals".[2] Anderson described its bass and drum solos as a presentation of the fight and struggle that life presents between "sources of evil and pure love".[15] Howe is particularly fond of his guitar solo at the beginning, which to him was "spine-chilling ... it was heavenly to play",[35] and uses a Gibson Les Paul Junior.[34] Howe's outro guitar solo was more improvised and jazz-oriented at first, but the rest of the group felt dissatisfied with the arrangement. Anderson suggested that Howe pick several themes from the album and combine them, which Howe did with "a more concise, more thematic approach".[36] During one of Wakeman's absences from the studio, White came up with the piano sequence for the closing "Nous sommes du soleil" section.[6]

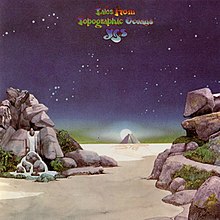

Cover

The album was packaged as a gatefold sleeve designed and illustrated by Roger Dean, who had also designed the art for Fragile, Close to the Edge, and Yessongs.[37] Each of them carried a loose narrative thread that Dean did not continue for Tales from Topographic Oceans. The album's design was discussed during an in-depth conversation Dean and Anderson had in 1973 during a flight from London to Tokyo via Anchorage, Alaska, during the Close to the Edge tour. Prior to the flight, Dean had completed the front cover to The View over Atlantis (1969) by John Michell, and "the wives and girlfriends made a cake ... and we all had some. I have no idea what was in it but from London to Anchorage, I was stoned ... But from Anchorage to Tokyo, I couldn't stop talking. And I was telling Jon all about this book, about patterns in the landscape and dragon lines, and we were flying hour after hour after hour over the most amazing landscapes ... So the idea of ... a sort of magical landscape and an alternative landscape ... that informed everything: the album cover, the merchandising, the stage."[38]

Dean, who primarily describes himself as a landscape painter, wished to convey his enthusiasm for landscapes within the album's artwork. He stressed that nothing depicted in the design is made up, and that everything in it exists for real.[39] Painted using watercolour and ink, the front depicts fish circling a waterfall under several constellations of stars. In his 1975 book Views, Dean wrote: "The final collection of landmarks was more complex than ... intended because it seemed appropriate to the nature of the project that everyone who wanted to contribute should do so. The landscape comprised amongst other things, some famous English rocks taken from Dominy Hamilton's postcard collection. These are, specifically: Brimham Rocks, the last rocks at Land's End, the Logan Rock at Treen and single stones from Avebury and Stonehenge. Jon Anderson wanted the Mayan temple at Chichen Itza with the sun behind it, and Alan White suggested using markings from the plains of Nazca. The result is a somewhat incongruous mixture, but effective nonetheless."[40] The original pressing of the sleeve included a slipstream in the background by the fish that was removed from future reissues. Although it was not a part of the original design, Anderson persuaded Dean to incorporate it after it was painted, so Dean drew it on a clear cel and had it photographed with and without the slipstream. Dean thought the idea still did not work and used the original for the album's advertisements and posters.[41]

In 2002, readers of Rolling Stone magazine voted the album's cover as the best cover art of all time.[42]

Release

The album was finished in the first week of November 1973, and aired on British radio several times before its release in stores.[43] It was set for broadcast on David Jensen's show on Radio Luxembourg on 8 November, but according to Anderson, the radio station somehow received blank tapes, resulting in dead air after the album was introduced.[44][45] Two more radio broadcasts followed, one on Your Mother Wouldn't Like It hosted by Nicky Horne on Capital Radio on 9 November, and on Rock on Radio One with Pete Drummond on BBC Radio 1 the following day.[44]

The album was released in the UK on 7 December 1973,[46] followed by its North American release on 9 January 1974.[47] It was a commercial success for the group; following a change in industry regulations by the British Phonographic Industry for albums to qualify for a Gold disc in April 1973, the album became the first UK record to reach Gold certification based on pre-orders alone after 75,000 orders were made.[48] It was number 1 on the UK Album Chart for two consecutive weeks and peaked at number 6 on the US Billboard Top LPs chart.[49] The album was certified Gold in the UK on 1 March 1974[46] and in the US on 8 February 1974, the latter for 500,000 copies sold.[50]

Reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| All About Jazz | |

| AllMusic | |

| Pitchfork | 2.2/10[53] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | C[54] |

| Rolling Stone | (unfavourable)[55] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Early reviews

The album received an initial divided reception from British critics. Robert Sheldon for The Times termed the music as "rockophonic", and selected "The Ancient" as a piece of music that "will be studied twenty-five years hence as a turning point in modern music".[57] The Guardian newspaper thought Anderson's "high-pitched and carefully modulated voice ... seemed at ease and control".[58] Steve Peacock reviewed the album and a live performance of it for Sounds magazine using the headlines "Wishy washy tales from the deep" and "Close to boredom".[59] Critic and Yes biographer Chris Welch reviewed the album for Melody Maker and wrote: "It is a fragmented masterpiece, assembled with loving care and long hours in the studio. Brilliant in patches, but often taking far too long to make its various points, and curiously lacking in warmth or personal expression". He thought "Ritual" brought the "first enjoyable moments" of the entire album, "where Alan's driving drums have something to grip on to and the lyrics of la la la speak volumes. But even this cannot last long and cohesion is lost once more to the gods of drab self-indulgence."[60] For New Musical Express, Steve Clarke, who had listened to the album for two months and saw the band perform the album live once, declared the album "a great disappointment", coming from the strength of Close to the Edge and notes the "colour and excitement" that the group usually puts on their albums was missing. He thought Wakeman's abilities were restricted, and a lack of "positive construction" in the music which too often loses itself to "a wash of synthetic sounds". Howe's guitar adopts the same tone as Wakeman's keyboards, which bored Clarke, but Anderson was praised in helping carry the music through with his "frail, pure and at times very beautiful" voice. Clarke concluded with a hope of Yes making a return to "real songs" which demonstrate their musicianship better.[61]

The album also received mixed reviews in America. Record World magazine considered it "by far the most progressive album to date" and displays the talents of each band member well, particularly Wakeman's.[62] A review in Billboard said the four sides produce mixed results, with Anderson's "weighty spiritual concept" having "indigestible lyrics that are fortunately outplayed by the band's rich, sweeping playing" and praised Wakeman's keyboards in particular. It concluded with "Ritual (Nous sommes du soleil)" as the most "complete" track.[63] In his negative review for Rolling Stone, Gordon Fletcher described the record as "psychedelic doodles" and thought it suffers from "over-elaboration" compared to more successful songs on Fragile and Close to the Edge. He complained about the album's length, Howe's guitar solos on "The Ancient", and the percussion section on "Ritual", but praised Wakeman for his "stellar performance" throughout and believed the keyboardist was the "most human of the group". Fletcher singled out the acoustic guitar section from "The Ancient" as the album's high point.[55] Cash Box magazine praised the album with its "spectacular cuts" making a "phenomenal" record, and noted the band "are as much in touch with the bright future of their art form as they are with its rich, traditional past". Wakeman's "inspirational" playing was also pointed out which "sparkles" throughout the album. It concluded with "one of this year's best without doubt."[64]

Later reviews

Retrospectively, Bruce Eder of AllMusic thought the album contains "some of the most sublimely beautiful musical passages ever to come from the group, and develops a major chunk of that music in depth and degrees in ways that one can only marvel at, though there's a big leap from marvel to enjoy. If one can grab onto it, Tales is a long, sometimes glorious musical ride across landscapes strange and wonderful, thick with enticing musical textures".[52] In its fortieth anniversary issue from 1992, NME selected Tales from Topographic Oceans as their "40 Records That Captured The Moment".[65] In 1996, Progression magazine writer John Covach wrote that it is Tales from Topographic Oceans, not Close to the Edge, that represents the band's true hallmark of the first half of their 1970s output and their "real point of arrival". He pointed out "the playing is virtuosic throughout, the singing innovative and often complex, and the lyrics mystical and poetic. All this having been asserted ... even the most devoted listener to Tales is also forced to admit that the album is in many ways flawed. Tracks tend to wander a bit ... and the music therefore is perhaps not as focussed as it might be." He notes that while Howe "set a new standard for rock guitar", he thought Wakeman's parts were not used properly and that the keyboardist was instead "relegated to the role of sideman".[27] Author and critic Martin Popoff called the album the "black hole of Yes experiences, the band dissipating, expanding, exploding and imploding all at once", though he thought it contained "some fairly accessible music".[66]

Band members

In 1984, when Yes had released the commercially successful album 90125 (1983), Anderson looked back on Tales from Topographic Oceans as "difficult in some respects", but felt it was "stupid to even think about defending it."[67] In 1990, he said that he was pleased with three quarters of the album, with the remaining quarter "not quite jelling", but the tight deadline to finish it meant there was little time to make the necessary changes.[68] Squire recalled the album as an unhappy period in the band's history, and commented on Anderson's attitude then: "Jon had this visionary idea that you could just walk into a studio, and if the vibes were right ... the music would be great at the end of the day ... It isn't reality".[69] Wakeman continues to hold a mostly critical view. In 2006, he clarified that there are some "very nice musical moments in Topographic Oceans, but because of the format of how records used to be we had too much for a single album but not enough for a double, so we padded it out and the padding is awful ... but there are some beautiful solos like "Nous sommes du soleil" ... one of the most beautiful melodies ... and deserved to be developed even more perhaps."[70]

Reissues

Anderson spoke about his wish to edit the album and reissue it as a condensed 60-minute version with remixes and overdubs, but the plan was affected by "personality problems".[68] The album was first remastered for CD by Joe Gastwirt in 1994.[71] It was remastered again by Bill Inglot in 2003 as an "expanded" version on Elektra/Rhino Records, which features a restored two-minute introduction to "The Revealing Science of God" not included on the original LP but previously released on the 2002 box set In a Word: Yes (1969–). The set includes studio run-throughs of the same track and "The Ancient".[72] The 2003 edition was included in the band's 2013 studio album box set, The Studio Albums 1969–1987.[73]

Tales from Topographic Oceans was reissued with new stereo and 5.1 surround sound mixes completed by Steven Wilson in October 2016 on the Panegyric label. The four-disc set was made available on CD and Blu-ray or DVD-Audio and includes the new mixes, bonus and previously unreleased mixes and tracks, and expanded and restored cover art.[74]

Tour and Wakeman's departure

Yes had planned to start touring the album with an American leg from October 1973, but it was cancelled to allow more time for the band to complete it.[75] The Tales from Topographic Oceans Tour visited Europe and North America between November 1973 and April 1974, with a two-hour set of Close to the Edge and Tales from Topographic Oceans performed in their entirety, plus encores. The set was altered as it progressed, with "The Revealing Science of God" dropped for some early shows in 1974, and "The Remembering" removed completely from March.[76]

Yes brought four times as much stage equipment than their previous tours, which included an elaborate stage set designed by Roger Dean and his brother Martyn and consisted of fibreglass structures, dry ice effects, a rotating drum platform surrounding White, and a tunnel that the band emerged from. During one show, the structure around White that opened and closed failed to operate, leaving him trapped. White claimed the incident was the inspiration behind a scene depicted in the rock mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap (1984).[77] The UK leg saw Yes sell out the Rainbow Theatre in London for five consecutive nights, marking the first time a rock band achieved the feat.[48] The first show was to be filmed by the BBC for broadcast on The Old Grey Whistle Test and on radio, but it never came to fruition.[78] The North American leg included two sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden in New York City that grossed over $200,000.[79] The band spent £5,000 on a hot air balloon which was decorated with the album's artwork and tethered in each city they performed in the US.[80]

During the UK leg, Wakeman announced his decision to leave the band at its conclusion. His boredom and frustration from playing the whole of Tales from Topographic Oceans culminated during a show in Manchester where his keyboard technician brought him a curry, which he proceeded to eat on stage.[81] Anderson felt he had pushed Wakeman too far, as he was unsatisfied with one of his keyboard solos in the set and had constantly asked him to get it right.[82] When the tour finished, Wakeman declined to attend rehearsals for their next album and confirmed his exit on 18 May 1974, his twenty-fifth birthday; later that day, he found out his solo album, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, had entered the UK chart at number one.[83] Wakeman was replaced by Swiss keyboardist Patrick Moraz.[84]

Track listing

All music by Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, Chris Squire, Rick Wakeman, and Alan White. Lyrics noted in parentheses.

Side one

- "The Revealing Science of God (Dance of the Dawn)" (Anderson, Howe) – 20:27

Side two

- "The Remembering (High the Memory)" (Anderson, Howe, Squire, Wakeman, White) – 20:38

Side three

- "'The Ancient' (Giants Under the Sun)" (Anderson, Howe, Squire) – 18:34

Side four

- "Ritual (Nous Sommes du Soleil)" (Anderson, Howe) – 21:35

Personnel

Yes

- Jon Anderson – lead vocals, harp, percussion

- Steve Howe – guitars, electric sitar, lute, backing vocals

- Chris Squire – bass guitar, backing vocals

- Rick Wakeman – keyboards

- Alan White – drums, percussion

Production

- Yes – production

- Eddy Offord – engineering, production

- Bill Inglot – sound production

- Guy Bidmead – tapes

- Mansell Litho – plates

- Roger Dean – cover design and illustrations, band logo

- Brian Lane – co-ordination

- Steven Wilson – 2016 Definitive Edition mixes

Charts

| Chart (1973–1974) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[85] | 13 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[86] | 4 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[87] | 8 |

| Finnish Albums (Finnish Albums Chart)[88] | 27 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[89] | 26 |

| Italian Albums (Musica e Dischi)[90] | 16 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[91] | 8 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[92] | 8 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[93] | 1 |

| US Billboard 200[94] | 6 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[95] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[96] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[97] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

Citations

- ^ a b Welch 2008, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e Yogananda 1998, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d e Morse 1996, p. 44.

- ^ Bruford 2009, p. 72.

- ^ a b Solomon, Linda (30 March 1974). "Journey into time and space...". New Musical Express. p. 32. ProQuest 1777004487.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tales from Topographic Oceans [2016 Definitive Edition] (Media notes). Yes. Panegyric. 2016. GYRBD80001.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b c Howe 2020.

- ^ Welch 2008, p. 142.

- ^ a b c d Morse 1996, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Greene, Andy (11 October 2019). "Rick Wakeman on His Tumultuous History With Yes, Playing on Bowie's 'Space Oddity'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Mary (24 March 1974). "Yes does what it thinks is right". Green Bay Press-Gazette. p. 14. Retrieved 15 October 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kerner, Kenny (12 May 1973). "Rick Wakeman: A little bit yes, a little bit no" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. 34, no. 47. p. 35. Retrieved 20 October 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Chambers 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Squire, Chris (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:19:36–1:19:48 minutes in.

- ^ a b c d e f Tales from Topographic Oceans (Media notes). Atlantic Records. 1973. K 80001.

- ^ Anderson, Jon (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:20:01–1:20:21 minutes in.

- ^ Carson, Phil (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:18:14–1:19:13 minutes in.

- ^ Wakeman, Rick (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:20:04–1:20:45 minutes in.

- ^ a b c d e Roche, Peter. Jon Anderson of Yes raids rock vault, talks "Topographic Oceans" 40 years on. Examiner.com. (12 September 2013) Retrieved on 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Welch 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Squire, Chris (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:22:14–1:22:20 minutes in.

- ^ Romano 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Clarke, Steve (15 November 1975). "New music and old arguments". New Musical Express. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Ayres & Osbourne 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Tait, Michael (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:20:58–1:21:16 minutes in.

- ^ Luby, Nigel (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:21:16–1:21:20 minutes in.

- ^ a b Covach, John (Winter 1996). "Progressive or Excessive? Uneasy Tales from Topographic Oceans". Progression.

- ^ Iommi 2011.

- ^ Chambers 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Halliwell & Hegarty 2011, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Morse 1996, p. 47.

- ^ Mead, David (15 March 2018). "Steve Howe: "Guitars always give me a feeling of complete freedom"". Music Radar. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Morse 1996, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Tiano, Mike (21 January 1995). "Notes from the Edge #124 – Conversation with Steve Howe conducted 27 November 1994". Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Morse 1996, p. 49.

- ^ "Ask YES – Friday 17th May 2013 – Steve Howe". YesWorld. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Thorgerson & Powell 1999, p. 142–143.

- ^ Brodsky, Greg (21 October 2015). "Roger Dean Interview: Getting Close To The Edge". Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Rich (18 March 2015). "Cover Story: Yes – Tales From Topographic Oceans". Team Rock. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Dean 1975.

- ^ Tiano, Mike (2008). "NFTE #308: Conversation with Roger Dean from 3 September 2008". Notes from the Edge. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (24 July 2003). "Dreaming Between The Grooves". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Yes set sail" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 5. Retrieved 20 October 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ a b Popoff 2016, p. 45.

- ^ Jon Anderson on Classic Artists: Yes DVD. Bonus Interviews.

- ^ a b "British album certifications: Yes – Tales from Topographic Oceans". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 21 May 2016. Enter "Tales from Topographic Oceans" in the field Keywords and select the option Title in the Search by field. Click Search.

- ^ Tales from Topographic Oceans (Media notes). Elektra/Rhino Records. 2003. 8122-73791-2.

- ^ a b Wooding 1978, p. 114.

- ^ "Tales from Topographic Oceans – Charts & Awards". Allmusic. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum: Searchable Database: Tales from Topographic Oceans". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Kelman, John (8 October 2016). "Yes: Tales from Topographic Oceans (Definitive Edition)". allaboutjazz.com. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ a b Tales from Topographic Oceans at AllMusic

- ^ Dahlen, Chris; Leone, Dominique; Tangari, Joe (8 February 2004). "Pitchfork: Album Reviews: Yes: The Yes Album / Fragile / Close to the Edge / Tales from Topographic Oceans / Relayer / Going for the One / Tormato / Drama / 90125". pitchfork.com. Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: Y". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved 9 March 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Gordon (28 March 1974). "Psychedelic Doodles: Record Review of Yes's "Tales from Topographic Oceans"". Rolling Stone. p. 49.

- ^ Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian David (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon & Schuster. p. 895. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Boone & Covach 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Hedges 1982, p. 91–92.

- ^ Peacock, Steve (1 December 1973). "Yes-Close to Boredom". Sounds.

- ^ Welch, Chris (1 December 1973). "Yes–Adrift on the Oceans: Record review of Yes' Tales from Topographic Oceans". Melody Maker: 64.

- ^ Clarke, Steve (19 January 1974). "YES: "Tales from Topographic Oceans" (Atlantic)". New Musical Express. p. 10. ProQuest 1777020962.

- ^ "Hits of the Week – "Yes, Tales from Topographic Oceans"" (PDF). Record World. 26 January 1974. p. 1. Retrieved 25 October 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Top Album Picks – YES: Tales from Topographic Oceans" (PDF). Billboard. 26 January 1974. p. 66. Retrieved 25 October 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Album Reviews – Tales from Topographic Oceans – Yes" (PDF). Cash Box. 19 January 1974. p. 29. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "NME List: 40 Records That Captured The Moment". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Popoff 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Anderson, Jon. Band Interviews from 9012Live [DVD] (2006).

- ^ a b Morse 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Morse 1996, p. 44–45.

- ^ Wakeman, Rick (2007). Classic Artists: Yes. Disc One (DVD). Image Entertainment. 1:24:09–1:24:49 minutes in.

- ^ "Yes: Tales from Topographic Oceans (CD – Atlantic / Elektra / Rhino #7567826832)". AllMusic. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Yes: Tales from Topographic Oceans (CD – Warner Bros. / WEA #WPCR-11685)". AllMusic. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Yes: The Studio Albums 1969–1987". AllMusic. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Release Date and Contents For Upcoming Steven Wilson Remix Of Yes' Tales From Topographic Oceans". MusicTAP. 25 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Atkinson, Rick (23 December 1973). "No, Pink Floyd's not splitting". The Record. p. B12. Retrieved 24 October 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Steve. "Forgotten Yesterdays". Steve Sullivan. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (7 August 2015). "Alan White on Chris Squire, Yes' New Tour and Cruise to the Edge: Exclusive Interview". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Green Light for Yes TV". Melody Maker. 13 October 1973. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Welch 2008, p. 143.

- ^ Wooding 1978, p. 115.

- ^ Wooding 1978, p. 110.

- ^ Welch 2008, p. 147.

- ^ Wakeman 1995, p. 124–125.

- ^ Thodoris, Από (18 June 2014). "Interview: Patrick Moraz (Solo, YES, The Moody Blues)". Hit-Channel. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 4991a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Yes – Tales from Topographic Oceans" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Sisältää hitin: Levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1961: Y > Yes" (in Finnish). Sisältää hitin / Timo Pennanen. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Yes – Tales from Topographic Oceans" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Classifiche". Musica e Dischi (in Italian). Retrieved 27 May 2022. Set "Tipo" on "Album". Then, in the "Artista" field, search "Yes".

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005 (in Japanese). Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Yes – Tales from Topographic Oceans". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Yes | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Yes Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "A party for the Yes". Billboard. 11 May 1974. p. 76. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "British album certifications – Yes – Tales From Topographic Oceans". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "American album certifications – Yes – Tales From Topographic Oceans". Recording Industry Association of America.

Books

- Ayres, Chris; Osbourne, Ozzy (2010). I Am Ozzy. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-56989-7.

- Boone, Graeme M.; Covach, John (1997). Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535662-5.

- Bruford, Bill (2009). Bill Bruford: The Autobiography: Yes, King Crimson, Earthworks, and More. Jawbone Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906002-23-7.

- Chambers, Stuart (2002). Yes: An Endless Dream of '70s, '80s and '90s Rock Music. ISBN 1-894263-47-2.

- Dean, Roger (1975). Views [2009 Edition]. Collins Design. ISBN 978-0-06-171709-3.

- Halliwell, Martin; Hegarty, Paul (2011). Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock Since the 1960s. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-4411-1480-8.

- Hedges, Dan (1982). Yes: An Authorized Biography. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-98751-9.

- Howe, Steve (2020). All My Yesterdays. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-785581-79-3.

- Iommi, Tony (2011). Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81955-1.

- Morse, Tim (1996). Yesstories: "Yes" in Their Own Words. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-14453-1.

- Popoff, Martin (2016). Time and a Word: The Yes Story. Soundcheck Books. ISBN 978-0-9932120-2-4.

- Romano, Will (2010). Mountains Come Out of the Sky: The Illustrated History of Prog Rock. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-375-6.

- Thorgerson, Storm; Powell, Aubrey (1999). 100 Best Album Covers: The Stories Behind the Sleeves. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7513-0706-8.

- Wakeman, Rick (1995). Say Yes! An Autobiography. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-62151-6.

- Watkinson, David (2000). Yes: Perpetual Change: Thirty Years of Yes. Plexus. ISBN 0-85965-297-1.

- Welch, Chris (2008). Close to the Edge: The Story of Yes. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84772-132-7.

- Wooding, Dan (1978). Rick Wakeman: The Caped Crusader. Granada Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-7091-6487-6.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (1998). Autobiography of a Yogi (13 ed.). Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 0-87612-079-6.

DVD media

- Various band members and associates (18 June 2007). Classic Artists: Yes (DVD). Disc 1 of 2. Image Entertainment. ASIN B000PTYPSY.

External links

- Official Yes website at YesWorld