Talk:Sustainability/History/Archive 4

| This page is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

History (final draft)

This brief account includes both the evolution of thinking about sustainability and the major historical events that have influenced human global sustainability.

Early civilizations

In early human history the energy and resource demands of nomadic hunter-gatherers was small. The use of fire and desire for specific foods may have altered the natural composition of plant and animal communities. Between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago, agriculture emerged in various regions of the world.[1] Agrarian communities depended largely on their environment and the creation of a "structure of permanence."[2] Societies outgrowing their local food supply or depleting critical resources either moved on or faced collapse.

Archeological evidence suggests that the first civilizations were Sumer, in southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and Egypt, both dating from around 3000 BCE. By 1000 BCE, civilizations became established in India, China, Mexico, Peru and in parts of Europe.[3][4]

Sumer illustrates issues central to the sustainability of human civilization.[5] Sumarian cities practiced intensive, year-round agriculture (from ca. 5300 BCE). The surplus of storable food created by this economy allowed the population to settle in one place instead of migrating after wild foods and grazing land. It also allowed for a much greater population density. The development of agriculture in Mesopotamia required significant labour resources to build and maintain an irrigation system. This, in turn, created political hierarchy, bureaucracy, and religious sanction, along with standing armies to protect the emergent civilization. Intensified agriculture allowed for population increase, but also led to deforestation in upstream areas, (which increased flooding), and over-irrigation, which raised soil salinity. While there was a shift from the cultivation of wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley, yields continually declined. Decreasing agricultural production and other factors, led to the decline of the civilization. During the period from 2100 BC to 1700 BC, it is estimated that the population declined by nearly sixty percent.[6][5]

Civilisations similarly thought to have eventually fallen because of poor management of resources include the Mayans, Anasazi and Easter Islanders.[7][8] Cultures of shifting cultivators and horticulturists have existed in New Guinea and South America and larger agrarian communities in China, India and elsewhere have farmed in the same localities for centuries. Polynesian cultures have maintained stable communities for between 1,000 and 3,000 years on small islands with minimal resources, and still practice management systems including rahui and kaitiaki to control human pressure on these resources[9].

Emergence of industrial societies

Technological advances over several millennia gave humans increasing control over the environment. But it was the Western industrial revolution of the 17th to 19th centuries that tapped into the vast growth potential of the energy in fossil fuels. Coal was used to power ever more efficient engines and later to generate electricity. Modern sanitation systems and advances in medicine protected large populations from disease[11]. Such conditions led to a human population explosion and unprecedented industrial, technological and scientific growth that has continued to this day. From 1650 to 1850 the global population doubled from around 500 million to 1 billion people.[12]

Concerns about the environmental and social impacts of industry were expressed by some Enlightenment political economists and in the Romantic movement of the 1800s. Overpopulation was discussed in an essay by Thomas Malthus (see Malthusian catastrophe), while John Stuart Mill foresaw the desirability of a "stationary state" economy, thus anticipating concerns of the modern discipline of ecological economics.[13][14][15][16][17] In the late 19th century, Danish botanist, Eugenius Warming, was the first to study physiological relations between plants and their environment, heralding the scientific discipline of ecology.[18]

Early 20th century

By the 20th century, the industrial revolution had led to an exponential increase in the human consumption of resources. The increase in health, wealth and population was perceived as a simple path of progress. However, in the 1930s economists began developing models of non-renewable resource management (see Hotelling's Rule) and the sustainability of welfare in an economy that uses non-renewable resources (Hartwick's Rule).

Ecology had now gained acceptance as a scientific discipline and many concepts now fundamental to sustainability were being explored. These included: the interconnectedness of all living systems in a single living planetary system, the biosphere; the importance of natural cycles (of water, nutrients and other chemicals, materials, waste); and the passage of energy through trophic levels of living systems.

Mid 20th century: environmentalism

Following the deprivations of the great depression and World War II the developed world entered a period of escalating growth. A gathering environmental movement pointed out that there were environmental costs associated with the many material benefits that were now being enjoyed. Innovations in technology (including plastics, synthetic chemicals, nuclear energy) and the increasing use of fossil fuels, were transforming society. Modern industrial agriculture—the "Green Revolution" — was based on the development of synthetic fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides which had devastating consequences for rural wildlife, as documented in Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962).

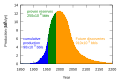

In 1956, M. King Hubbert's peak oil theory predicted the inevitable peak of oil production, first in the United States (between 1965 and 1970), then in successive regions of the world, with a global peak expected thereafter.[19] In the 1970's environmentalism's concern with pollution, the population explosion, consumerism and the depletion of finite resources was highlighted through the release of Small Is Beautiful, by E.F. Schumacher, in 1973, and the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth, in 1975.

Late 20th century

Increasingly environmental problems were viewed as global in scale.[20][21][22][23] The 1973 and 1979 energy crises demonstrated the extent to which the global community had become dependent on a nonrenewable resource and led to a further increase in public awareness of issues of sustainability.

While the developed world was considering the problems of unchecked development the developing countries, faced with continued poverty and deprivation, regarded development as essential to provide the necessities of life. In 1980 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature had published its influential World Conservation Strategy,[24] followed in 1982 by its World Charter for Nature,[25] which drew attention to the decline of the world’s ecosystems.

The United Nation's World Commission on Environment and Development (the Brundtland Commission) made suggestions in regard to the conflict between the environment and development. The Commission suggested that development was acceptable, but must be sustainable development that would meet the needs of the poor, but not worsen environmental problems. Humanity’s demand on the planet has more than doubled over the past 45 years as a result of population growth and increasing individual consumption. In 1961, almost all countries in the world had more than enough capacity to meet their own demand; by 2005, the situation had changed radically, with many countries able to meet their needs only by importing resources from other nations.[27]

A direction toward sustainable living by increasing public awareness and adoption of recycling, and renewable energies begins to occur. The development of renewable sources of energy in the 1970's and 80's, primarily in wind turbines and photovoltaics, and increased use of hydro-electricity, presented some of the first sustainable alternatives to fossil fuel and nuclear energy generation. These developments led to construction of many of the first large-scale solar and wind power plants during the 1980's and 90's. The 1990's saw the small-scale reintroduction of the electric car. These factors, further raised public awareness of issues of sustainability, and many local and state governments in developed countries began to implement small-scale sustainability policies.

21st century: global awareness

Since the turn of the century, more specific and detailed initiatives have led to widespread understanding and awareness of the importance of sustainability prompted by a sudden global awareness of the threat posed by the human-induced enhanced greenhouse effect produced largely by forest clearing and the burning of fossil fuels.[29]Some environmentalists look toward an environmental technology or ecological economics perspective, as a more inclusive and ethical model for society, than traditional neoclassical economics.[30][31] Emerging concepts include: the Car-free movement, Smart Growth (more sustainable urban environments), Life Cycle Assessment (the Cradle to Cradle analysis of resource use and environmental impact over the life cycle of a product or process), the Ecological Footprint, green design, dematerialization (increased recycling of materials), decarbonisation (removing dependence on fossil fuels) and much more.

The work of Bina Agarwal and Vandana Shiva amongst many others, has brought some of the cultural wisdom of traditional, sustainable agrarian societies into the academic discourse on sustainability, and also blended that with modern scientific principles.[32]

Rapidly advancing technologies mean it is now technically possible to achieve a transition of economies, energy generation, water and waste management, and food production towards sustainable practices using methods of systems ecology and industrial ecology.[33]

Notes

- ^ Wright, R. (2004). A Short History of Progress, p. 55. Toronto: Anansi. ISBN 0-88784-706-4.

- ^ Clarke, William C. (1977). "The Structure of Permanence: The Relevance of Self-Subsistence Communities for World Ecosystem Management," from Subsistence and Survival, Bayliss-Smith and Teachem (eds). London: Academic Press, pp. 363-384.

- ^ Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Wright, R., p. 42.

- ^ a b Wright, R., pp. 86- 116

- ^ Thompson, William R. (2004). "Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation" (pdf). Journal of World Systems Research.

- ^ Diamond, J. 1997. Guns, germs and steel: the fates of human societies. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-06131-0

- ^ Diamond, Jared M. (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed ISBN 1-586-63863-7

- ^ Cook Islands National Environment Service

- ^ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of a the UPM (Madrid)

- ^ Hilgenkamp, K. Environmental Health: Ecological Perspectives 2005. Published by Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0763723770, 9780763723774.

- ^ Goudie A. 2006. The Human Impact on the Natural Environment. 6th edn. Blackwell, Carlton.

- ^ Martinez-Alier, J. 1987. Ecological economics. Blackwell, Oxford.

- ^ Schumacher, E.F. 1973. Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. Blond and Briggs, London.

- ^ Daly, H. 1991. Steady-State Economics (2nd ed.). Island Press,Washington, D.C.

- ^ Daly, H. E. 1999. Ecological Economics and the Ecology of Economics. E Elgar Publications, Cheltenham.

- ^ Daly, H.E. and Cobb, J. B. 1989. For the Common.

- ^ Goodland, R.J. (1975) The tropical origin of ecology: Eugen Warming’s jubilee. Oikos, 26, 240-245. [1]

- ^ "Oil, the Dwindling Treasure" National Geographic, June 1974

- ^ Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. (1972).

The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books. ISBN 0-87663-165-0 - ^ World Wide Fund for Nature (2008). Living Planet Report 2008.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. The full range of reports are available here: Guide to the Millennium Assessment Reports.

- ^ Turner, G.M. 2008. A comparison of The Limits to Growth with 30 years of reality. Global Environmental Change 18: 397-411.

- ^ An updated version of the World Conservation Strategy, http://coombs.anu.edu.au/~vern/caring/caring.html

- ^ UN General Assembly (28 October 1982). World Charter for Nature. 48th plenary meeting, A/RES/37/7.

- ^ e-digest environment statistics

- ^ http://www.panda.org/news_facts/publications/living_planet_report/index.cfm Living Planet Report W.W.F. 2008

- ^ UCN. 2006. The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the Twenty-first Century. Report of the IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting, 29-31 January, 2006 http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/iucn_future_of_sustanability.pdf

- ^ U.S. Department of Commerce. Carbon Cycle Science. NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory.

- ^ http://www.eoearth.org/by/Topic/Ecological%20economics

- ^ Costanza R. (2003). Early History of Ecological Economics and ISEE. Internet Encyclopaedia of Ecological Economics.

- ^ Ganguly, M. Vandana Shiva: Seeds of Self-Reliance. Time.com, Heros for the Green Century.

- ^ Kay, J.J. "On Complexity Theory, Exergy and Industrial Ecology: Some Implications for Construction Ecology.",Construction Ecology: Nature as the Basis for Green Buildings,edited by Kibert, C., Sendzimir, J., Guy, B., pp 72-107, Spon Press, 2002

Final draft comments

I've removed the editing markers and I think it is almost ready for uploading - just pending Nick's comments. The only other thing I can think of is the question of the environment/social/economic diagram. TP is proposing to address that in the Definition section, so we can remove it from this section when that is finalized. Sunray (talk) 08:25, 6 January 2009 (UTC)

- It looks great! We do need to address the diagram at some stage. Nick carson (talk) 12:13, 6 January 2009 (UTC)

- The diagram has been around for a long time because it does a good job. Ecology and environment are the same thing in the diagram. skip sievert (talk) 16:47, 6 January 2009 (UTC)

I've moved this section to the talk page. The diagram remains in this section for now, however, as mentioned, Travelplanner is working on a proposal for with respect to the diagram and we can decide its fate based on that. Great work all. Sunray (talk) 16:57, 6 January 2009 (UTC)

- A major hurdle overcome - the planet should be pleased!! Could we now archive everything except a copy of the version that finally went up? Granitethighs (talk) 01:56, 7 January 2009 (UTC)