Tammany Hall

The Tammany Hall logo on its headquarters at 44 Union Square | |

| Named after | Tamanend (anglicized to "Tammany"), Lenape leader |

|---|---|

| Formation | May 12, 1789 |

| Founder | William Mooney |

| Founded at | New York City, New York |

| Dissolved | 1967 |

| Merger of | Tammanies |

| Type | Democratic pressure group |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Headquarters | Several: last was at 233 Madison Avenue at East 37th Street, New York City |

| Location |

|

| Services | Patronage |

| William Mooney (first) J. Raymond Jones (last) | |

Key people | Aaron Burr, William M. Tweed, Fernando Wood, Richard Croker, Lewis Nixon, Carmine DeSapio, Charles Francis Murphy |

| Affiliations | Democratic Party |

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local political machine of the Democratic Party and played a major role in controlling New York City and New York State politics, and helped immigrants, most notably the Irish, rise in American politics from the 1850s into the 1960s. Tammany usually controlled Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years following the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854, and used its patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders; after 1850, the vast majority were Irish Catholics due to mass immigration from Ireland during and after the Irish Famine of the late 1840s.

After 1854, it expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's rapidly expanding immigrant community, which functioned as its base of political capital. The business community appreciated its readiness, at moderate cost, to cut through regulatory and legislative mazes to facilitate rapid economic growth.

By 1872, Tammany had an Irish Catholic "boss". In 1928, a Tammany hero, New York Governor Al Smith, won the Democratic presidential nomination. However, the organization also served as an engine for graft and political corruption, most infamously under William M. "Boss" Tweed in the mid-19th century. The Tammany ward boss or ward heeler, as wards were the city's smallest political units from 1786 to 1938, served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage.

By the 1880s, Tammany was building local clubs that appealed to social activists from the ethnic middle class.[1][2] At its peak the machine had the advantage of a core of solid supporters, and usually exercised control of politics and policymaking in Manhattan; it also played a major role in the state legislature in Albany.

Charles Murphy acted as boss from 1902 to 1924.[3] "Big Tim" Sullivan was the Tammany leader in the Bowery, and the machine's spokesman in the state legislature.[4] In the early 20th century, the two men promoted Tammany as a reformed agency dedicated to the interests of the working class. The new image deflected attacks and secured a following among the emerging ethnic middle class. In the process Robert F. Wagner became a powerful United States Senator, and Smith served four terms as governor and was the Democratic presidential nominee in 1928.[5][6]

Tammany's influence waned during the 1930s and early 1940s, when it engaged in a losing battle with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the state's governor (1929–1932) and later U.S. President (1933–1945). In 1932, after Mayor Jimmy Walker was forced from office when his bribery was exposed, Roosevelt stripped Tammany of federal patronage. Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor on a Fusion ticket and became the first anti-Tammany mayor to be re-elected. A brief resurgence in Tammany power in the 1950s, under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio, was met with Democratic opposition, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, Herbert Lehman, and the New York Committee for Democratic Voters. By the mid-1960s, Tammany Hall ceased to exist.

Although not common in modern interpretations and evaluations of the effects of the organisation, Tammany was frequently criticised in the 19th century for being directly responsible for the nativism, anti-Catholic sentiment, and the rise of the Know Nothing Party in the preceding century due to fears about Tammany's influence and tactics.

Tammany Hall in the 18th and 19th centuries[edit]

1789–1840[edit]

The Tammany Society was founded in New York on May 12, 1789, originally as a branch of a wider network of Tammany Societies, the first of which had been formed in Philadelphia in 1772.[7] The society was originally developed as a club for "pure Americans".[8] The name "Tammany" comes from Tamanend, a Native American leader of the Lenape. The society adopted many Native American words and also their customs, going so far as to call their meeting hall a wigwam.

The first Grand Sachem, as the leader was titled, was William Mooney, an upholsterer of Nassau Street.[9] Although Mooney claimed the top role in the early organization, it was a wealthy merchant and philanthropist named John Pintard who created the society's constitution and declared it to be "[a] political institution founded on a strong republican basis whose democratic principles will serve in some measure to correct the aristocracy of our city." Pintard also established the various Native American titles of the society.[10]

The Society had the political backing of the Clinton family in this era, whereas the Schuyler family backed the Hamiltonian Federalists, and the Livingstons eventually sided with the anti-federalists and the Society.[11] The Society assisted the federal government in procuring a peace treaty with the Creek Indians of Georgia and Florida at the request of George Washington in 1790 and also hosted Edmond-Charles Genêt, representative of the New French Republic after the French Revolution toppled the old regime,[12] in 1793.

By 1798, the society's activities had grown increasingly political. High-ranking Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr saw Tammany Hall as an opportunity to counter Alexander Hamilton's Society of the Cincinnati.[8] Eventually Tammany emerged as the center of Democratic-Republican Party politics in the city.[9] Burr used Tammany Hall as a campaign asset during the election of 1800, in which he acted as Democratic-Republican campaign manager. Some historians believe that without Tammany, President John Adams might have won New York State's electoral votes and won reelection.[13]

Early cases of political corruption involving Tammany Hall came to light during the group's feud with local politician Dewitt Clinton. The feud began in 1802 after Clinton accused Aaron Burr of being a traitor to the Democratic-Republican Party.[14] Clinton's uncle, George Clinton, was jealous of Burr's achievements and positions. However, George was too old to compete with young Aaron Burr, and so he left it to his nephew.[14] One of Burr's political cohorts and the author of Burr's biography was a businessman, a newspaper editor, and a sachem of the Society named Matthew L. Davis. Other Burr operatives included William P. Van Ness and John Swartwout, the latter of whom dueled with De Witt Clinton in 1802 in New Jersey.[15]

In 1803, Clinton left the United States Senate and became Mayor of New York City. As mayor, Clinton enforced a spoils system and appointed his family and partisans to positions in the city's local government. Tammany Hall soon realized its influence over the local political scene was no match for that of Clinton,[16] in part because Burr's support among New York City's residents greatly faded after he shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Tammany continued to support him for a time, but eventually pressure from the public persuaded the organization to no longer affiliate themselves with Burr.[17]

Matthew Davis would go on to refine the Society as a political machine, beginning in 1805. The Society, with Davis's guidance, received a state charter as a charitable organization, organized the General Committee of Tammany Hall, and used the General Committee to decide leadership within the Democratic-Republican party in New York City from that point forward.[15] In December 1805, Dewitt Clinton reached out to Burr's supporters to gain enough support to resist the influence of the powerful Livingston family.[17] The Livingstons, led by former New York City mayor Edward Livingston, backed New York Governor Morgan Lewis, who presented a significant challenge to Clinton.[18] The Tammany Hall sachems agreed to meet with Clinton in secret, on February 20, 1806,[18] and agreed to back him, on the condition that the Clintons would once again acknowledge Aaron Burr as a Democratic-Republican and stop using "Burrism" as a reason to object to their ideas.[14] The Clintons readily agreed to these conditions, but did not intend to honor them. When the Sachems caught wind of this, the feud between Tammany Hall and Clinton resumed.[17]

Tammany Hall became a locally organized machine dedicated to stopping Clinton and Federalists from rising to power in New York.[19] However, local Democratic-Republicans began to turn against Tammany Hall.[20] From 1806 to 1809 public opinion forced the local Common Council to crack down on Tammany Hall.

The resulting investigations found that a number of Tammany officials were guilty of embezzlement and illegal activity.[21] For example, one official, Benjamin Romaine was found guilty of using his power to acquire land without payment and was ultimately removed from his office as City Comptroller[18] despite the Council being controlled by Democratic-Republicans.[18]

Following the disclosures, the Federalists won control of the state legislature and the Democratic-Republican Party maintained a slim majority of the local government in New York City.[22] Matthew Davis convinced other sachems to join him in a public relations stunt that provided income for the Society. The shallow graves of some Revolutionary War soldiers who died in British prison ships were located in Wallabout Bay (near the Brooklyn Navy Yard). Davis announced that the Society was going to provide proper burials for these soldiers with a monument dedicated to their memory on nearby land owned by a fellow sachem.

The remains were, in fact, reburied. The Society led a flotilla, on April 13, 1808, in thirteen boats, to Brooklyn, with each boat carrying a symbolic coffin. A dedication ceremony was held at Wallabout Bay and the state voted to provide the Society $1,000 to build a monument. The Society pocketed the money and the monument was never built.[23] However, Tammany Hall did not learn their lesson,[17] and instead of fixing the problem of corruption, Wortman, one of the chief powers at the time, created a committee, consisting of one member from each ward, that would investigate and report in general meetings who were friends or enemies.[20]

During 1809–1810, the feud between Tammany Hall and the Clintonites intensified, as each party continued attacking each other.[20] One of the Clintonites, James Cheetham, wrote extensively about Tammany and its corrupt activities, using his position as State Printer and publishing his work in the American Citizen newspaper.[24] Tammany Hall did not take lightly to these activities and managed to remove Cheetham from his position as State Printer.[24] At the same time, Clinton attempted to cooperate with Tammany Hall in order to create a state dominated by Democratic-Republicans. In an attempt to persuade Tammany sachems, he pulled his support for Cheetham, who was his protégé at the time.[17] Cheetham's loss of Clinton's support angered him, and he responded by releasing details of Tammany and Clinton's attempts at cooperating to control the state.[17] On September 18, 1810, James Cheetham died after an attack that was possibly Tammany-related.[17]

Between the years 1809 and 1815, Tammany Hall slowly revived itself by accepting immigrants and by secretly building a new wigwam to hold meetings whenever new Sachems were named.[25] The Democratic-Republican Committee, a new committee which consisted of the most influential local Democratic-Republicans, would now name the new Sachems as well.[26]

When Dewitt Clinton decided to run for president in 1811, Tammany Hall immediately accused Clinton of treason to his party, as well as attempting to create a family aristocracy. Even though New York State voted for Clinton the following year, Democratic-Republicans could not help but see Clinton's actions as being exactly what Tammany had accused them of. With this, most Democratic-Republicans in New York City turned away from Clinton.

When Tammany Hall positioned itself to support the War of 1812 and to support the Embargo Act, many others who supported the war joined Tammany Hall.[27] In fact, during this time, because of its success in establishing political opinion, Tammany Hall was able to grow stronger and even gained support from Federalist members who supported the war.[28]

The Native American titles of the Society were disused during and after the War of 1812 in response to attacks from Native Americans on White Americans.[29] During this time we see Tammany Hall's earliest application of its most notable technique—turning support away from opposing parties and rewarding newly joined members.[28] This was the case for Federalists who joined the Society.

Tammany Hall managed to gain power, as well as reduce Clinton and his followers to just a small fraction.[30] In 1815, Tammany Hall grand sachem John Ferguson defeated Dewitt Clinton and was elected mayor. However, in 1817, Clinton, with his success on the Erie Canal project, gained so much popularity that, despite his weak position after the War and Tammany's immense efforts, he once again became Governor of New York and Tammany Hall fell again.[31]

Another factor leading to Clinton's popularity was his patronage of immigrants. The origins of Tammany Hall were based on representing "pure" or "native" Americans. This meant that the Hall dismissed immigrants such as the Irish and Germans, although the Germans were more politically averse. On April 24, 1817, discontent with this treatment led to a huge riot during a Tammany general committee session.[31] Until his death in 1828, Clinton would remain Governor of New York, with the exception of the two-year period of 1823–1824, and Tammany Hall's influence waned.

Martin Van Buren and his Albany Regency soon began controlling the policy of Tammany Hall. This included pushing for the state referendum that eventually granted the right to vote in New York State to all free white men in 1821. After voting rights were expanded, Tammany Hall could further increase its political power.[32] Tammany Hall soon began to accept Irish immigrants as members and eventually became dependent on them to maintain viability as a political force.[33]

During the 1828 U.S. presidential election, Tammany Hall leaders met with Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson and agreed to endorse him after he promised to give them control over the allocation of some federal jobs.[34] After he was elected president, Jackson fulfilled his promise.[34] After 1829, Tammany Hall became the city affiliate of the Democratic Party, controlling most of the New York City elections afterwards.[35]

In the 1830s the Loco-Focos, an anti-monopoly and pro-labor faction of the Democratic Party, became Tammany's main rival for votes by appealing to workingmen. However, Tammany's political opponent remained the Whigs. During the 1834 New York City mayoral governor election, the first city election in which the popular vote elected the mayor, both Tammany Hall and the Whig party, from their headquarters at the Masonic Hall, battled in the streets for votes and protected polling locations in their respective regions from known opposition voters.[36] During the 1838 state election for governor, the rival Whig party imported voters from Philadelphia, paying $22 a head for votes in addition to paying for votes at their polling places. Tammany Hall operatives continued their practice of paying prisoners of the almshouses for votes and also paying for votes at their polling places.[37]

The Tammany Hall "ward boss" served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage. New York City used the designation "ward" for its smallest political units from 1686 to 1938. The 1686 Dongan Charter divided the city into six wards and created a Common Council which consisted of an alderman and an assistant alderman elected from each ward. In 1821, the Common Council's authority was expanded so it would also elect the city's mayor, who had previously been appointed by the state government. In 1834, the state constitution was amended to require the city's mayor to be elected by direct popular vote.

In 1834 Cornelius Van Wyck Lawrence, a pro-Tammany Democrat, would become the first mayor ever elected by popular vote in the city's history.[38]

Immigrant support[edit]

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the Society expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's ever-expanding immigrant community, which functioned as a base of political capital. During the 1840s, hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants arrived in New York City to escape the Great Famine and Tammany saw its power grow greatly.[39]

Tammany Hall's electoral base lay predominantly with New York's burgeoning immigrant constituency, which often exchanged political support for Tammany Hall's patronage. In pre-New Deal America, the extralegal services that Tammany and other urban political machines provided often served as a rudimentary public welfare system.

Irish immigrants became even more influential during the mid-1840s to early 1850s. With the Great Famine in Ireland, by 1850, more than 130,000 immigrants from Ireland lived in New York City. Since the newly arrived immigrants were in deep poverty, Tammany Hall provided them with employment, shelter, and even citizenship sometimes.[40] For example, the group gave referrals to men looking for work and legal aid to those who needed it. Tammany Hall would also provide food and financial aid to families with sick or injured breadwinners. In an example of their involvement in the lives of citizens, in the course of one day, Tammany figure George Washington Plunkitt assisted the victims of a house fire; secured the release of six drunks by speaking on their behalf to a judge; paid the rent of a poor family to prevent their eviction and gave them money for food; secured employment for four individuals; attended the funerals of two of his constituents (one Italian, the other Jewish); attended a Bar Mitzvah; and attended the wedding of a Jewish couple from his ward.[41]

Tammany Hall took full advantage of the burgeoning numbers of Irish immigrants to gather more votes. By 1855, 34 percent of New York City's voter population was composed of Irish immigrants, and many Irish men came to dominate Tammany Hall.[42]

Tammany Hall also served as a social integrator for immigrants by familiarizing them with American society and its political institutions and by helping them become naturalized citizens. One example was the naturalization process organized by William M. Tweed. Under Tweed's regime, "naturalization committees" were established. These committees were made up primarily of Tammany politicians and employees, and their duties consisted of filling out paperwork, providing witnesses, and lending immigrants money for the fees required to become citizens. Judges and other city officials were bribed and otherwise compelled to go along with the workings of these committees.[43] In exchange for all these benefits, immigrants assured Tammany Hall they would vote for their candidates.[35] By 1854, the support Tammany Hall received from immigrants would firmly establish the organization as the leader of New York City's political scene.[35] With the election of Fernando Wood, the first person to be supported by the Tammany Hall machine, as mayor in 1854, Tammany Hall would proceed to dominate the New York City political arena until Fiorello La Guardia's mayoralty after the election of 1933.[35]

Political gangs and the Forty Thieves[edit]

After Fernando Wood's losing reelection run for U.S. Congress in 1842, he left politics for a while to work on his shipping business. A power vacuum of sorts existed through the 1840s for Tammany Hall, which became preoccupied with fights between political gangs fighting over turf. These gangs included the Dead Rabbits, the Bowery Boys, Mike Walsh's Spartan Association, the Roach Guards, the Plug Uglies, the Wide-Awakes, and Captain Isaiah Rynders' Empire Club. Rynders was the leader of Tammany's Sixth Ward and a member of the General Committee who was also said to have been responsible for coordinating all political-related gang activity. Many of these leaders coordinated their activities from saloons, which became a target of prohibitionists and reformers.[44]

At the start of the 1850s, the city economy began to pick up and Tammany members would profit. The City Council of New York during these years would be known as the most corrupt up to this time. The new City Council of 1852 swept in Tammany politicians to replace the outgoing Whig ones, who did little with their power.

The new council was made up of two sets of 20 members, a twenty-member Board of Aldermen and a twenty-member Board of Assistant Aldermen. This new council would be known as the Forty Thieves. Each Alderman had the power to appoint police (including precinct officers) and license saloons within his district. Together, the Aldermen possessed the power to grant franchises for streetcar lines and ferries. Each Alderman also sat as judge in criminal courts, determining who sat for juries and choosing which cases came to trial. On paper, these aldermen received no pay. A number of real estate deals followed with suspicious transaction amounts, including a purchase of a pauper's burial ground on Ward's Island and the sale of city property occupying Gansevoort Market near the western end of 14th Street to Reuben Lovejoy, an associate of James B. Taylor, a friend of many of the Aldermen. Other deals included expensive fireworks displays and bribes for ferry and railroad operations (Jacob Sharp for the Wall Street Ferry and various applicants for the Third Avenue railroad). Aldermen would also resort to creating strike legislation to obtain quick cash: a spurious bill would be introduced that would obviously financially harm someone, who would then complain to legislators. These legislators would then kill the bill in committee for a fee. As the press became aware of the Forty Thieves tactics, a reform movement instigated for a change in the city charter in June 1853 so that city work and supply contracts were awarded to the lowest bidder, franchises were awarded to the highest bidder, and bribery was punished harshly.[44]

Fernando Wood era[edit]

Fernando Wood attempted several small business ventures in the city during the 1830s while simultaneously increasing his involvement with Tammany Hall. These early business attempts failed, but by 1836, at the age of 24, he became a member of the Society and became known for resolving the dispute between the Loco-Focos and the conservatives of the Hall. At the age of 28, in 1840, Wood was put up by Tammany Hall for a U.S. congressional seat, which he won.

After Wood's service in Congress, he became a successful businessman through real estate dealings and was elected mayor of New York City in 1854. William Tweed said of Wood, "I never yet went to get a corner lot that I didn't find Wood had got in ahead of me." In his first term as mayor, Wood ensured the police force was responsive to his needs and convinced commissioners to allow him to fire officers not performing their duties. He was then accused of only hiring Democrats to replace those fired officers.

Wood defied tradition and ran for a second term as mayor in 1856, which irked some of his Tammany associates. During the campaign, his police force acted as his henchmen and Wood took a portion of their salary for his war chest ($15 to $25 for captains and a lesser amount for patrolmen). On election day, he gave his policemen some time off to vote, during which time his affiliated Dead Rabbits gang protected polling places. Wood won his second term.

The Republicans, who made gains upstate, created a new state charter for New York City in response to this concentration of power in one man, which included more elected (instead of appointed) city department heads and officers. The Republicans also consolidated a separate police force, the Metropolitan Police, from the police forces of Kings, Richmond, and Westchester counties. The Republicans in the state legislature also moved the city mayoral elections to odd years, making the next election for mayor in December 1857.

A power struggle followed between Wood's Municipal Police and the newly created Metropolitan Police, as well as between the Dead Rabbits and the nativist Bowery Boys. Tammany Hall did not put Wood up for reelection in December 1857 in light of the Panic of 1857 and a scandal involving him and his brother, Benjamin Wood.[45]

Mozart Hall[edit]

As a result of the scandal, Fernando Wood left or was expelled from Tammany in 1858 to form a third party, the Mozart Hall Democracy, or Mozart Hall, named after their building at the corner of Broadway and Bleecker Street. Wood ran for mayor in 1859, with the backing of James Gordon Bennett's New York Tribune, as the champion of workingclass Irish and German immigrants against the "kid glove, scented, silk stocking, poodle-headed, degenerate aristocracy."[46] The Republicans attempted to combine their efforts with Tammany, but the deal could not be consummated, making it a three-candidate race, which Wood won with 38.3% of the vote. It was Wood's second and last term as mayor, serving until 1862.[45][46][47]

Mozart Hall was a major player in city politics through the 1860s and was successful in getting additional school wards for German communities. During the Civil War, Democrats were divided between "War Democrats" – who wanted victory on the battlefield but objected to what they considered radical Republican legislation and the erosion of civil rights by Lincoln – and "Peace Democrats", who favored the restoration of the Union as it existed before the war with slavery in place, or, alternately, peace without reunion (espoused by an extreme faction). William M. Tweed, most of Tammany's politicians, and many prominent businessmen were in the "War" faction, while Mozart Hall was the center of the "Peace" Democrats in New York. While the division between Tammany and Mozart had worked in Wood's favor in 1859, in 1861 it caused Republican George Opdyke to be elected, over Wood and Tammany's C. Godfrey Gunther, with barely more than a third of the vote.[48][47]

After the war, Mozart Hall aligned itself more closely with Tammany, and gradually lost influence. It disbanded in 1867.[47][49]

Tweed regime[edit]

Tammany's control over the politics of New York City tightened considerably under Tweed. In 1858, Tweed capitalized on the efforts of Republican reformers to rein in the Democratic city government to obtain a position on the County Board of Supervisors, which he then used as a springboard to other appointments, and to have his friends placed in various offices. From this position of strength, he was elected "Grand Sachem" of Tammany, which he then used to take functional control of the city government. With his protégés elected governor of the state and mayor of the city, Tweed was able to expand the corruption and kickbacks of his "Ring" into practically every aspect of city and state governance.

Although Tweed was elected to the State Senate, his true sources of power were his appointed positions to various branches of the city government. These positions gave him access to city funds and contractors, thereby controlling public works programs. This benefitted his pocketbook and those of his friends, but also provided jobs for the immigrants, especially Irish laborers, who were the electoral base of Tammany's power.[50]

According to Tweed biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman:

It's hard not to admire the skill behind Tweed's system ... The Tweed ring at its height was an engineering marvel, strong and solid, strategically deployed to control key power points: the courts, the legislature, the treasury and the ballot box. Its frauds had a grandeur of scale and an elegance of structure: money-laundering, profit sharing and organization.[51]

Under "Boss" Tweed's dominance, the city expanded into the Upper East and Upper West Sides of Manhattan, the Brooklyn Bridge was begun, land was set aside for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, orphanages and almshouses were constructed, and social services – both directly provided by the state and indirectly funded by state appropriations to private charities – expanded to unprecedented levels. All of this activity, of course, also brought great wealth to Tweed and his friends. It also brought them into contact and alliance with the rich elite of the city, who either fell in with the graft and corruption, or else tolerated it because of Tammany's ability to control the immigrant population, of whom the "uppertens" of the city were wary.

James Watson, who was a county auditor in Comptroller Dick Connolly's office and who also held and recorded the ring's books, died a week after his head was smashed by a horse in a sleigh accident on January 21, 1871. Although Tweed guarded Watson's estate in the week prior to Watson's death, and although another ring member attempted to destroy Watson's records, a replacement auditor, Matthew O'Rourke, associated with former sheriff James O'Brien provided city accounts to O'Brien.[52] Further, Tammany demonstrated inability to control Irish laborers in the Orange riot of 1871 that also began Tweed's downfall. Campaigns to topple Tweed by The New York Times and Thomas Nast of Harper's Weekly began to gain traction in the aftermath of the riot, and disgruntled insiders began to leak the details of the extent and scope of the Tweed Ring's avarice to the newspapers. Specifically, O'Brien forwarded the city's financial accounts to The New York Times. The New York Times, at that time the only Republican associated paper in the city, was then able to reinforce stories they had previously published against the ring.[52] The Committee of Seventy was formed in September 1871 by prominent reformers to examine the misdeeds of the Tweed ring.

Tweed was arrested and tried in 1872. After he died in Ludlow Street Jail in 1878 political reformers took over the city and state governments.[50] Following Tweed's arrest, Tammany survived, but was no longer controlled by Protestants and was now dependent on leadership from bosses of Irish descent.[33]

1870–1900 [edit]

Tammany did not take long to rebound from Tweed's fall. Reforms demanded a general housecleaning, and former county sheriff "Honest John" Kelly was selected as the new leader. Kelly was not implicated in the Tweed scandals and was a religious Catholic related by marriage to Archbishop John McCloskey. He cleared Tammany of Tweed's people and tightened the Grand Sachem's control over the hierarchy.

His success at revitalizing the machine was such that in the election of 1874, the Tammany candidate, William H. Wickham, succeeded the unpopular outgoing reformist incumbent, William F. Havemeyer (who died shortly thereafter), and Democrats generally won their races, delivering control of the city back to Tammany Hall.[53] A noted statue of John Kelly is located in the hall, the work of Irish sculptor Robert Cushing.[54]

1886 mayoral election[edit]

The mayoral election of 1886 was a seminal one for the organization. Union activists had founded the United Labor Party (ULP), which nominated political economist Henry George, the author of Progress and Poverty, as its standard-bearer. George was initially hesitant about running for office but was convinced to do so after Tammany secretly offered him a seat in Congress if he would stay out of the mayoral race. Tammany had no expectation of George being elected but knew that his candidacy and the new party were a direct threat to their own status as the putative champions of the working man.[55]

Having inadvertently provoked George into running, Tammany now needed to field a strong candidate against him, which required the cooperation of the Catholic Church in New York, which was the key to getting the support of middle-class Irish American voters. Richard Croker, Kelly's right-hand man, had succeeded Kelly as Grand Sachem of Tammany, and he understood that he would also need to make peace with the non-Tammany "Swallowtail" faction of the Democratic Party to avoid the threat that George and the ULP posed, which was the potential re-structuring of the city's politics along class lines and away from the ethnic-based politics which had been Tammany's underpinning all along. To bring together these disparate groups, Croker nominated Abram Hewitt as the Democratic candidate for mayor. Not only was Hewitt the leader of the Swallowtails, but he was noted philanthropist Peter Cooper's son-in-law and had an impeccable reputation. To counter both George and Hewitt, the Republicans put up Theodore Roosevelt, the former state assemblyman.[56]

In the end, Hewitt won the election, with George out-polling Roosevelt, whose total was some 2,000 votes less than the Republicans had normally received. Despite their second-place finish, things seemed bright for the future of the labor political movement, but the ULP was not to last, and was never able to bring about a new paradigm in the city's politics. Tammany had once again succeeded and survived.

More than that, Croker realized that he could use the techniques of the well-organized election campaign that the ULP had run. Because Tammany's ward-heelers controlled the saloons, the new party had used "neighborhood meetings, streetcorner rallies, campaign clubs, Assembly District organizations, and trade legions – an entire political counterculture"[57] to run their campaign. Croker now took these innovations for Tammany's use, creating political clubhouses to take the place of the saloons and involving women and children by sponsoring family excursions and picnics. The New Tammany appeared to be more respectable, and less obviously connected to saloonkeepers and gang leaders, and the clubhouses, one in every Assembly District, were also a more efficient way of providing patronage work to those who came looking for it; one simply had to join the club, and volunteer to put in the hours needed to support it.[58]

Hewitt turned out to be a terrible mayor for Croker, due to his nativist views, and in 1888 Tammany ran Croker's hand-picked choice, Hugh J. Grant, who became the first New York-born Irish American mayor. Although Hewitt ran an efficient government, Croker viewed Hewitt as being too self-righteous and did not grant Croker the patronage jobs he was expecting from a mayor. Hewitt had also offended Irish voters by deciding not to review a St. Patrick's Day parade they requested of him.[59]

Grant allowed Croker free run of the city's contracts and offices, creating a vast patronage machine beyond anything Tweed had ever dreamed of a status which continued under Grant's successor, Thomas Francis Gilroy. With such resources of money and manpower – the entire city workforce of 1,200 was essentially available to him when needed – Croker was able to neutralize the Swallowtails permanently. He also developed a new stream of income from the business community, which was provided with "one stop shopping": instead of bribing individual officeholders, businesses, especially the utilities, could go directly to Tammany to make their payments, which were then directed downward as necessary; such was the control Tammany had come to have over the governmental apparatus of the city.[60]

Croker mended fences with labor as well, pushing through legislation which addressed some of the inequities which had fueled the labor political movement, making Tammany once again appear to be the "Friend of the Working Man" – although he was careful always to maintain a pro-business climate of laissez-faire and low taxes. Tammany's influence was also extended once again to the state legislature, where a similar patronage system to the city's was established after Tammany took control in 1892. With the Republican boss, Thomas Platt, adopting the same methods, the two men between them essentially controlled the state.[61]

Fassett Committee[edit]

The 1890s began with a series of what would be three political investigations into Tammany operations, reminiscent of the early 1870s. Platt was the key organizer of most of these committees, the first of which was the Fassett Committee of 1890. This first committee featured testimony from Croker's brother-in-law, revealing gifts of cash surrounding his hotel business. The recorded testimonies resulted in no indictments and the Democrats would not suffer in the elections of 1890 or 1892.

1894 mayoral election and the Lexow Committee[edit]

(The boss of Tammany Hall in New York, Richard Croker, and the boss of the Brooklyn political machine, Hugh McLaughlin, reach across the East River to shake hands in cooperation).

In 1894, Tammany suffered a setback when, fueled by the public hearings on police corruption held by the Lexow Committee based on the evidence uncovered by the Rev. Charles Parkhurst when he explored the city's demi monde undercover, a Committee of Seventy was organized by Council of Good Government Clubs to break the stranglehold that Tammany had on the city. Full of some of the city's richest men – J.P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, Abram Hewitt and Elihu Root, among others – the committee supported William L. Strong, a millionaire dry-goods merchant, for mayor, and forced Tammany's initial candidate, merchant Nathan Straus, co-owner of Macy's and Abraham & Straus, from the election by threatening to ostracize him from New York society.

Tammany then put-up Hugh Grant again, despite his being publicly dirtied by the police scandals. Backed by the committee's money, influence and their energetic campaign, and helped by Grant's apathy, Strong won the election handily, and spent the next three years running the city on the basis of "business principles", pledging an efficient government and the return of morality to city life. The election was a Republican sweep statewide: Levi Morton, a millionaire banker from Manhattan, won the governorship, and the party also ended up in control of the legislature.[62] Croker was absent from the city for three years starting at the onset of the Lexow Committee, residing in his homes in Europe.

Still, Tammany could not be kept down for long, and in 1898 Croker, aided by the death of Henry George – which took the wind out of the sails of the potential re-invigoration of the political labor movement – and returned from his stay in Europe, shifted the Democratic Party enough to the left to pick up labor's support, and pulled back into the fold those elements outraged by the reformers' attempt to outlaw Sunday drinking and otherwise enforce their own authoritarian moral concepts on immigrant populations with different cultural outlooks. Tammany's candidate, Robert A. Van Wyck, easily outpolled Seth Low, the reform candidate backed by the Citizens Union, and Tammany was back in control. Its supporters marched through the city's streets chanting, "Well, well, well, Reform has gone to Hell!"[63]

Mazet Investigation[edit]

A final state investigation began in 1899 at the prompting of newly elected Theodore Roosevelt. This Mazet Investigation was chaired by Republican assemblyman Robert Mazet and led by chief counsel Frank Moss, who had also participated in the Lexow Committee. The investigation revealed further detail about Croker's corporate alliances and also yielded memorable quotes from police chief William Stephen Devery and Croker. This was also the committee that began probing Croker about his holdings in ice companies.[64]

Despite occasional defeats, Tammany was consistently able to survive and prosper. Under leaders such as Charles Francis Murphy and Timothy Sullivan, it maintained control of Democratic politics in the city and the state.

Tammany Hall in the 20th century[edit]

Machine politics versus the reformers[edit]

The politics of the consolidated city from 1898 to 1945 revolved around conflicts between the political machines and the reformers. In quiet times the machines had the advantage of the core of solid supporters and usually exercised control of city and borough affairs; they also played a major role in the state legislature in Albany. Tammany, for example, from the 1880s onward built a strong network of local clubs that attracted ambitious middle-class ethnics.[1][2]

In times of crisis however, especially in the severe depressions of the 1890s and the 1930s, the reformers took control of key offices, notably the mayor's office. The reformers were never unified; they operated through a complex network of independent civic reform groups; each focused its lobbying efforts on its own particular reform agenda. The membership included civic-minded, well-educated middle-class men and women, usually with expert skills in a profession or business, who deeply distrusted the corruption of the machines.[65] The consolidation of Brooklyn, western Queens County and Staten Island with Manhattan and the Bronx in 1898 multiplied the power of these reform groups, so long as they could agree on a common agenda, such as consolidation itself.[66]

There was no citywide machine. Instead, Democratic machines flourished in each of the boroughs, with Tammany Hall in Manhattan the most prominent. They typically had strong local organizations, known as "political clubs", as well as one prominent leader often called the "boss". Charles Murphy was the highly effective but quiet boss of Tammany Hall from 1902 until his death in 1924.[3] "Big Tim" Sullivan was the Tammany leader in the Bowery and the machine's spokesman in the state legislature.[4]

Republican local organizations were much weaker, but they played key roles in forming reform coalitions. Most of the time they looked to Albany and Washington for their sphere of influence.[67][full citation needed][68]

Seth Low, the president of Columbia University, was elected the reform mayor in 1901. He lacked the common touch and lost much of his working-class support when he listened to dry Protestants eager to crack down on the liquor business.[69][70]

Murphy wanted to clean up Tammany's image and sponsored progressive era reforms benefiting the working class through his two protégés, Governor Al Smith and Robert F. Wagner. Ed Flynn, a protégé of Murphy who became the boss in the Bronx, said Murphy always advised that politicians should have nothing to do with gambling or prostitution and should steer clear of involvement with the police department or the school system.[71]

A new challenge to Tammany came from William Randolph Hearst, a powerful newspaper publisher who wanted to be president. Hearst was elected to Congress with Tammany support, was defeated for mayor after a bitter contest with Tammany and won Tammany support for his unsuccessful quest for the governorship of New York. Hearst did manage to dominate Tammany mayor John F. Hylan (1917–25), but he lost control when Smith and Wagner denied Hylan renomination in 1925. Hearst then moved back to his native California.[72]

Power vacuum and the Seabury Commission (1925–1932)[edit]

After Charles Francis Murphy's death in 1924, Tammany's influence on Democratic politics began its wane. Murphy's successor as the Boss in 1924 was George W. Olvany, the first Tammany Hall Boss to have received a college education. When Tammany's Jimmy Walker became the city mayor over Hylan in 1925, the hall was poised for advantage. Olvany was not an overbearing Boss, and the familiar Tammany Hall schemes from a pre-Murphy era began. Police received protection money from shopkeepers, rackets surrounded the fish and poultry markets, as well as the docks, and licensing fees for various professions were increased with Tammany Hall middlemen reaping the benefits.

This bright period of influence for Tammany Hall was short-lived. The population of Manhattan, Tammany's stronghold, no longer represented the population of the city as other boroughs such as Brooklyn and the Bronx made gains. Franklin D. Roosevelt's election as New York State Governor in 1928 further reduced Tammany Hall's power. Although Al Smith guided Roosevelt to the governorship, Roosevelt did not request Smith's advice once there and instead appointed Bronx Boss Edward J. Flynn as New York's Secretary of State. The stock market crash of 1929 and the increasing press attention on organized crime during the Prohibition era also contributed to the hall's decline.

Olvany resigned as the Boss in 1929, and John F. Curry was tapped to fill the role. Curry beat Eddy Ahearn for the role, Al Smith's choice and often considered to be an abler man. Although he looked the part, Curry was not considered smart enough to fill the role and proceeded to make a series of poor decisions on behalf of Tammany.[73]

The organized crime robbery of a city judge and leader of the Tepecano Democratic Club, Albert H. Vitale, during a dinner party on December 7, 1929, and the subsequent recovery of the stolen goods from gangsters following a few calls from Magistrate Vitale, prompted the public to request a closer look at the ties of organized crime, law enforcement and the judicial system within the city. Vitale was accused of owing $19,600 to Arnold Rothstein and was investigated by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court for failing to explain how he accrued $165,000 over four years while receiving a total judicial salary of $48,000 during that same period. Vitale was removed from the bench.

A further investigation by U.S. district attorney Charles H. Tuttle discovered that Brooklyn Judge Bernard Vause was paid $190,000 in return for obtaining pier leases for a shipping company, and that another city judge, George Ewald had paid Tammany Hall $10,000 for the replacement seat of Judge Vitale. FDR responded by launching three investigations between 1930 and 1932, headed by Samuel Seabury, called the Seabury Commission. Another Tammany Hall associate, state Supreme Court Justice Joseph Force Crater, disappeared in August 1930, after the start of the first investigation, in what would become an unsolved case. Crater was president of a Tammany Hall Club on the Upper West Side.[74]

During questioning, Tammany associate and New York County Sheriff Thomas M. Farley denied that gambling took place in his political clubs and could not account for the frequent presence of associates of Arnold Rothstein. Other questioning focused on the combined police, court, and bail bonding scheme surrounding the improper arrest of prostitutes and innocent women. The outcome of these investigations included the dismissal of several corrupt judges, including the city's first female judge, Jean H. Norris, the resignation of Mayor Jimmy Walker, the indictment of Deputy City Clerk James J. McCormick and the arrest of State Senator John A. Hastings. Sheriff Thomas M. Farley was removed from office by Governor Roosevelt.[73]

La Guardia in, Tammany out: 1933 to 1945[edit]

In 1932, the machine suffered a dual setback when mayor Jimmy Walker was forced from office by scandal and reform-minded Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president of the United States. Tammany Hall leader John F. Curry and Brooklyn political boss John H. McCooey had joined forces to support Al Smith's candidacy.[75] Roosevelt and his lead campaign manager James Farley stripped Tammany of federal patronage, which had expanded under the New Deal, and passed it instead to Ed Flynn, boss of the Bronx, who had kept his district clean of corruption.[76]

Roosevelt also helped Republican Fiorello La Guardia become mayor on a Fusion ticket in 1933, thus removing even more patronage from Tammany's control.[77] After becoming mayor, LaGuardia reorganized the city cabinet with non-partisan officials and sought to develop a clean and honest city government.[77]

Tammany alderman Alford J. Williams died in December 1933; when the Board of Aldermen reconvened in January 1934 it defied party leadership and elected an ally of La Guardia as his successor.[78] The shock from this decision caused Tammany Bronx leader Augustus Pierce to collapse and die of a heart attack in the aldermanic chambers.[78]

As mayor, La Guardia successfully led the effort to have a new city charter adopted which would mandate a proportional representation method of electing members of the City Council. The measure won on a referendum in 1936.[77] After the new charter went into effect in 1938, the ward system which had allowed only a small number of people to serve on the City Council since 1686 ceased to exist, and the new 26-member New York City Council now had certain functions governed by the Board of Estimate.[79] La Guardia's appointees filled the board of magistrates and virtually every other long-term appointive office, and the power of Tammany Hall had now been reduced to a shadow of what it once was.[77]

La Guardia also greatly increased the number of city jobs awarded by the civil service system: roughly three-quarters of city positions required job seekers to take an exam in 1939, compared to only about half in 1933.[80] In 1937, La Guardia defeated Jeremiah T. Mahoney to become the first anti-Tammany "reform" Mayor to ever be re-elected in the city's history[77] and was again re-elected in 1941 before retiring in 1945.[77] His extended tenure weakened Tammany in a way that previous reform mayors had not.[77]

Tammany depended for its power on government contracts, jobs, patronage, corruption, and ultimately the ability of its leaders to control nominations to the Democratic ticket and swing the popular vote. The last element weakened after 1940 with the decline of relief programs such as the WPA and CCC that Tammany used to gain and hold supporters. Congressman Christopher "Christy" Sullivan was one of the last "bosses" of Tammany Hall before its collapse.

Criminal issues[edit]

Tammany had close ties to street gangs throughout the 19th Century, who provided services to Tammany on Election Day in return for legal protection the rest of the year.[81] Those relations largely collapsed with the rise of newer crime organizations that flourished during Prohibition; Tammany came to depend on figures such as Arnold Rothstein to maintain some measure of control, however limited, over them.[82] Rothstein's murder in 1928 weakened Tammany; it also contributed to the election of Fiorello La Guardia in 1933 and the appointment of Thomas E. Dewey as Special Prosecutor, appointed by Governor Herbert H. Lehman, in 1935.

Dewey obtained the conviction of powerful mobster and strong Tammany ally Lucky Luciano on racketeering charges in 1936. Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years;[83] While Luciano was still able to maintain control of the powerful Luciano crime family from prison until his sentence was commuted to deportation to Italy in 1946,[84] his conviction gave Dewey the prestige required to continue prosecution of organized crime figures and their political allies, particularly in Tammany Hall.

In 1939 Dewey, now Manhattan District Attorney, prosecuted longtime Tammany Hall boss Jimmy Hines on bribery charges.[85][8] Hines was convicted and sentenced to 4 to 8 years.[86] The loss of Hines would serve as a major blow to Tammany, as he had given the political machine strong ties to the city's powerful organized crime figures since the 1920s.[83] Several Tammany Hall officials affiliated with Hines and Luciano were also successfully prosecuted by Dewey.[83]

In 1943, Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan provided a transcript of a recorded phone message between Frank Costello and Judge Thomas A. Aurelio, a Tammany associate running for the state Supreme Court—the trial-level court within New York's judicial system—on both the Republican and Democratic tickets, in which Aurelio pledged his undying loyalty to Costello.[87] When Costello was called as a witness in Aurelio's disbarment proceedings he freely admitted that he had used his influence to make Michael Kennedy the new head of Tammany and to secure Aurelio's nomination.[88] While Aurelio avoided disbarment and even won reelection to his position on the bench, Kennedy resigned his position within Tammany in January 1944.[88]

Costello and Tammany went on to help elect former Brooklyn District Attorney William O'Dwyer to the mayorship in 1945.[88] O'Dwyer was reelected in 1949, then resigned the following year due to a bribery scandal that implicated both O'Dwyer and Costello and that led to the resignations of hundreds of police officers accused of protecting gambling operations and the replacement of all 336 members of the New York City Police Department's plainclothes division.[89]

Indian summer, 1950s[edit]

Although the Kefauver hearings, an investigation into organized crime, did not directly impact Tammany, it did not help its image regarding its apparent connection to organized crime.[90] O'Dwyer, now Ambassador to Mexico, returned in 1951 to testify about the bribery scandal and sought to deflect any accusations of wrongdoing, but was unable to offer any persuasive explanation for his visit to Costello's apartment in 1941, when he first sought Tammany's support in his campaign for Mayor.[88] O'Dwyer resigned as ambassador the following year, following the conviction of one of his close associates for accepting bribes.[88]

Tammany never recovered from prosecutions of the 1940s, but it staged a small-scale comeback in the early 1950s under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio, who succeeded in engineering the elections of Robert F. Wagner Jr., an outspoken liberal Democrat,[91] as mayor in 1953 and W. Averell Harriman as governor in 1954, while simultaneously blocking his enemies, especially Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr. in the 1954 race for state attorney general. Unlike previous Tammany bosses, however, DeSapio had promoted himself as a reformer and always made his decisions known to the public.[92]

The fact that DeSapio was of Italian descent also demonstrated that Tammany was no longer dominated by Irish-American politicians.[92] Under DeSapio's leadership, the ethnicity of Tammany Hall's leaders diversified.[92] However, DeSapio's close ties with the city's lead mobster Frank Costello, Luciano's self-appointed successor,[84] helped establish him as a corrupt figure.[92] During DeSapio's reign, Costello was the main person who influenced the decisions made by Tammany Hall officials.[92]

By 1956, however, Costello, who was convicted of tax evasion in 1954 and now controlled the Luciano family from prison, was engaged in a major power struggle with fellow associate Vito Genovese and his grip on power greatly weakened.[84] In 1957, Costello was released from prison after winning an appeal but officially abandoned his role as head of the Luciano family following a failed assassination attempt.[84]

In 1958, DeSapio's "reform" image was severely damaged after he ran his own candidate for the Senate, Frank Hogan.[92] New Yorkers now saw DeSapio as an old-time Tammany Hall boss, and Hogan would lose the Senate election to Republican Kenneth Keating;[92] Republican Nelson Rockefeller would also be elected governor the same year.[92] Democrats who once praised De Sapio now excoriated him.[92] In 1961, Wagner won re-election by running a reformist campaign that denounced his former patron, DeSapio, as an undemocratic practitioner of Tammany machine politics.[92] After World War II, a group of young World War II veterans and other reform-minded Democrats began the Lexington Democratic Club in response to being denied access to Tammany Hall politics by the old guard.[93][94] Eleanor Roosevelt organized a counterattack with Herbert H. Lehman and Thomas K. Finletter to form the New York Committee for Democratic Voters, a group dedicated to fighting Tammany. In 1961, the group helped remove DeSapio from power. The once mighty Tammany political machine, now deprived of its leadership, quickly faded from political importance, and by 1967 it ceased to exist; its demise as the controlling group of the New York Democratic Party was sealed when the Village Independent Democrats under Ed Koch wrested away control of the Manhattan party.

Leaders[edit]

There were two distinct entities: the Tammany Society, headed by a Grand Sachem elected annually on May 23; and the Tammany Hall political machine headed by a "boss". The following list names the political bosses, as far as could be ascertained. Tammany Hall operated with obfuscation in mind, so these public leaders may not represent actual leadership.[95]

|

|

Headquarters[edit]

Early years[edit]

In its very early days, the Tammany Society met in the back rooms of various taverns, most often in Barden's Tavern on Broadway near Bowling Green.[99] These back rooms served as unofficial campaign headquarters on election days.[100]

In 1791, the society opened a museum designed to collect artifacts relating to the events and history of the United States. Originally presented in an upper room of City Hall, it moved to the Merchant's Exchange when that proved to be too small. The museum was unsuccessful, and the Society severed its connections with it in 1795.[101]

Then, in 1798, the Society moved to more permanent and spacious quarters, the "Long Room" of "Brom" Martling's Tavern, at Nassau Street and Spruce Street, near where City Hall is today. Tammany controlled the space, which it dubbed "The Wigwam", and let other responsible political organizations it approved of use the room for meetings. This space became commonly known as "Tammany Hall".[99]

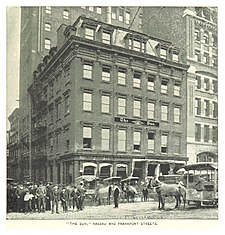

Their new headquarters had limitations as well as advantages, and in 1812 Tammany moved again, this time to a new five-story $55,000 building it built at the corner of Nassau and Frankfort streets, just a few blocks away. The new Tammany Hall had a large room that could accommodate up to 2,000 people for political and social events, and the rest of the building was run as a hotel. The Society was to remain there for 55 years.[102]

14th Street headquarters[edit]

By the 1860s, Tammany under Tweed had much greater influence – and affluence, so new headquarters was deemed desirable. The cornerstone for the new Tammany headquarters was laid on July 14, 1867, at 141 East 14th Street between Third Avenue and Fourth Avenue (the building at Nassau and Frankfort was sold to Charles Dana and his friends, who bought a newspaper, The Sun, and moved it there).[103]

When the leaders of the Society found that they had not raised enough funds, and needed $25,000 more, a meeting was held at which $175,000 was immediately pledged.[104] The new Wigwam was completed in 1868. It was not just a political clubhouse:

Tammany Hall merged politics and entertainment, already stylistically similar, in its new headquarters. ... The Tammany Society kept only one room for itself, renting the rest to entertainment impresarios: Don Bryant's Minstrels, a German theater company, classical concerts and opera. The basement – in the French mode – offered the Café Ausant, where one could see tableaux vivant, gymnastic exhibitions, pantomimes, and Punch and Judy shows. There was also a bar, a bazaar, a Ladies' Cafe, and an oyster saloon. All this – with the exception of Bryant's – was open from seven till midnight for a combination price of fifty cents.[105]

The building had an auditorium big enough to hold public meetings, and a smaller one that became Tony Pastor's Music Hall, where vaudeville had its beginnings.[106] The structure was topped off by a large-than-life statue of Saint Tammany.[104]

44 Union Square[edit]

In 1927 the building on 14th Street was sold, to make way for the new tower being added to the Consolidated Edison Building. The Society's new building at 44 Union Square, a few blocks north at the corner with East 17th Street, was finished and occupied by 1929.[107] When Tammany started to lose its political influence, and its all-important access to graft, it could no longer afford to maintain the 17th Street building, and in 1943 it was bought by a local affiliate of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Tammany left, and its leaders moved to the National Democratic Club on Madison Avenue at East 37th Street, and the Society's collection of memorabilia went into a warehouse in the Bronx.[108]

The building at 44 Union Square housed the New York Film Academy and the Union Square Theatre, and retail stores at street level, until a complete renovation of the building began in 2016.[109] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it in October 2013.[110] The renovation, which included a gutting of the interior and the installation of a glass-domed roof, was substantially completed by July 2020.[111][112]

In popular culture[edit]

- Tammany Hall is featured in the 1943 novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, in which they sponsor a family outing. Johnny and Katie Nolan debate the merit of the organization, with Johnny for and Katie opposed to it.

- Walt Kelly's comic strip Pogo (1948–1975) depicts a politically minded tiger, Tammananny, as one of the creatures who shows up in the swamp in election years, spouting ideas to help the reluctant Pogo campaign for President of the United States.

- The 1959 Broadway musical Fiorello! describes Fiorello H. La Guardia's 1933 campaign for Mayor of New York City against Tammany Hall.

- Samuel Hopkins Adams's 1959 posthumous novel Tenderloin about the battle between social reformer Charles Henry Parkhurst and the Tammany Hall political machine was produced as a successful Broadway musical, Tenderloin, in 1960.

- In 1990, a story in the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes featured Calvin "transmogrifying" himself into an elephant. Calvin later jokes to his neighbor Susie that he and his stuffed tiger Hobbes are the Republican Party and Tammany Hall. As Susie cannot see Calvin's elephant form, she does not get the joke, prompting Calvin to conclude that "political humor is too sophisticated for girls."[113]

- Tammany Hall is prominently featured in the 2002 film Gangs of New York, with Jim Broadbent portraying "Boss" Tweed.

- The 2007 area control board game "Tammany Hall" is based on Tammany Hall politics, with players vying for support from different immigrant populations in order to achieve dominance in New York City.[114]

- Tammany Hall features as a power-broking group in the 2012 TV series Copper, pulling strings behind the scenes in the Five Points neighborhood of New York City.

- Tammany Hall was an antagonist in the Clive Cussler 2016 novel The Gangster, part of Cussler's Isaac Bell series.

- A tiger referred to as the "Tammany Tiger" (a representation of Tammany Hall and corrupt politicians) appears in episodes 17 and 18 of The Unsleeping City II, a Dimension 20 actual-play show.

- The Aldermen grant and then revoke a railroad permit for the protagonist on the show The Gilded Age (TV series) during season 1, episode 3.

See also[edit]

- Big Tim Sullivan

- Five Points Gang

- History of New York City (1855–97) Tammany and Consolidation

- History of New York City (1898–1945)

- History of New York City (1946–77)

- Harlem Clubhouse

- Ice Trust Scandal

- Charles W. Morse

- Murray Hall (politician)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Technically, Costikyan was not leader of Tammany Hall itself, but of the New York Democratic Committee.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Peel, Roy V. The Political Clubs of New York City (1935)

- ^ a b Shefter 1978, p. 263-298.

- ^ a b Huthmacher (1965)

- ^ a b Czitrom 1991, p. 536-538.

- ^ Slayton, Robert A. Empire Statesman: The Rise and Redemption of Al Smith (2001). ch 6–15.

- ^ Huthmacher, J. Joseph. Senator Robert F. Wagner and the rise of urban liberalism (1968) ch 1–4

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb, ed. (1910), "Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico: N-Z", Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 30 (2), Washington: Smithsonian Institution: 683–684

- ^ a b c "Sachems & Sinners: An Informal History of Tammany Hall". Time Magazine. August 22, 1955. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "The History of New York State". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Allen pp. 5–6

- ^ Allen pp. 7, 10

- ^ Allen pp. 7–10

- ^ Parmet and Hecht, pp. 149–50

- ^ a b c Myers, p. 17

- ^ a b Allen pp. 13–14, 18

- ^ Myers, p. 21

- ^ a b c d e f g Myers, p. 28

- ^ a b c d Myers, p. 23

- ^ Myers, p. 24

- ^ a b c Myers, p. 26

- ^ Myers, pp. 27–30

- ^ Myers, p. 30

- ^ Allen p. 21

- ^ a b Myers, p. 27

- ^ Myers, pp. 36–38

- ^ Myers, p. 38

- ^ Myers, p. 39

- ^ a b Myers, p. 36

- ^ Allen p. 24

- ^ Myers, p. 35

- ^ a b Myers, p. 46

- ^ Allen pp. 27–50

- ^ a b Panayiotopoulos, Prodromos (2006). Immigrant enterprise in Europe and the USA. Routledge Studies in the Modern World Economy. p. 52. ISBN 978-0415353717.

- ^ a b "New York Election Results". Mahalo.com.

- ^ a b c d The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project, Tammany Hall, George Washington University, archived from the original on December 19, 2006

- ^ Allen pp. 42–43

- ^ Allen pp. 36,48

- ^ "A Brief History of Election Law in New York". Gotham Gazette. September 1, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "Tammany Hall: Boss Tweed & Thomas Nast". Racontours. 2011. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Tammany Hall". www2.gwu.edu. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Riordan 1963, p. 91-93.

- ^ Abdolhamidi, Shervin (November 7, 2016). "The Top 10 Secrets of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Political Machine That Ran NYC". www.untappedcities.com. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Connable and Silberfarb, p. 154

- ^ a b Allen pp. 54–62

- ^ a b Allen pp. 52–53, 63, 67–76

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace, p.862

- ^ a b c Bradley, James "Mozart Hall" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 861. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.865

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 862, 885. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace, p. 837 and passim

- ^ Ackerman 2005[page needed], quoted in Hamill, Pete (March 27, 2005). "'Boss Tweed': The Fellowship of the Ring". The New York Times (book review). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Allen, pp. 118–25

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p. 1027

- ^ "ROBERT CUSHING'S ART; WORK OF THE AGED SCULPTOR WHO HAS JUST PASSED AWAY. One of the Originators and Leaders of the Profession in This Country -- His Sudden Dentil, of Which Few Knew -- Works Which Will Hand His Name Down to Fame -- Ward and Macdonald Contemporaneous with Him". The New York Times. March 29, 1896. p. 26. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p. 1099

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1103–06

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p. 1100

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1106–08

- ^ Allen p. 175

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1108–09

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1109–10

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1192–94

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1206–08

- ^ Allen pp. 197–200

- ^ Richard Skolnik, "Civic Group Progressivism In New York City," New York History (1970) 51#5 pp. 411–39.

- ^ David C. Hammack, Power and Society: Greater New York at the Turn of the Century (1982) pp. 308–13

- ^ Jackson 1996, p. 914, 999, 1149–51.

- ^ Marvin G. Weinbaum, "New York County Republican Politics, 1897–1922: The Quarter-Century After Municipal Consolidation", New York Historical Society Quarterly (1966) 50#1 pp. 62–70.

- ^ Jackson 1996, p. 695, Seth Low.

- ^ Steven C. Swett, "The Test of a Reformer: A Study of Seth Low, New York City Mayor, 1902–1903", New-York Historical Society Quarterly (1960) 44#1 pp. 5–41

- ^ Golway 2014, p. 186.

- ^ Ben Proctor, William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910 (1998) ch 11

- ^ a b Allen pp. 233–50

- ^ Allen p. 242

- ^ "Curry and McCooey to Support Ticket; Roosevelt Held 'Luckiest Man' in Nation". The New York Times. July 3, 1932. p. 10. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. "Edward Flynn (1891–1953)". George Washington University. Archived from the original on December 19, 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "La Guardia Is Dead; City Pays Homage To 3-Time Mayor". The New York Times. September 21, 1947.

- ^ a b Lee, Dick (January 17, 1934). "Aldermen smash Tiger rule; shock kills Bronx boss". New York Daily News. Vol. 15, no. 176. p. 2. Retrieved March 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "About the City Council". New York City Council. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ Allen p. 256

- ^ Stolberg, Mary M. (1995). Fighting Organized Crime: Politics, Justice, and the Legacy of Thomas E. Dewey. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555532454. pp. 10-11

- ^ "National Affairs: Tammany Test". Time. July 8, 1929. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ a b c "truTV – Reality TV – Comedy".

- ^ a b c d "Articles/Biographies/Criminals/Costello, Frank". Free Information Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Jimmy Hines Trial". LIFE. Time Inc. August 29, 1938. p. 9. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "Hines, James J.: Newspaper Clippings from the Trials, 1938–1940". Harvard Law School Library. HOLLIS4380869. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010.The People of the State of New York v. James J. Hines, 284 N.Y. 93 258, 466 (App. Div. 1939).

- ^ Allen p. 258

- ^ a b c d e Maeder, Jay (August 14, 2017). "Tammany Hall scandal: Crime boss Frank Costello and the judge". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Samuels, David (October 2019). "The Mayor and the Mob". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Allen p. 271

- ^ Clarity, James F. (February 13, 1991). "Robert Wagner, 80, Pivotal New York Mayor, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kandell, Jonathan (July 28, 2004). "Carmine De Sapio, Political Kingmaker and Last Tammany Hall Boss, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013.

- ^ Allen p. 275

- ^ "About the club". lexclub.org. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Allen, p. 1

- ^ a b Wiles, David (2003). "Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall Machine". New York State University at Albany. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Sheppard, Si (2014). ""If it wasn't for Roosevelt you wouldn't have this job": The Politics of Patronage and the 1936 Presidential Election in New York". New York History. 95 (1): 41–69. doi:10.1353/nyh.2014.0051. JSTOR newyorkhist.95.1.41. S2CID 159116571.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (June 23, 2012). "Edward N. Costikyan, Adviser to New York Politicians, Is Dead at 87". New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Allen, pp. 7–8

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p. 322

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p. 316

- ^ Allen, p. 24

- ^ O'Brien, Frank Michael (1916). The Story of the Sun: New York, 1833–1918. New York: George H. Doran company. p. 229.

- ^ a b Allen, pp. 99–100

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p. 995

- ^ Wurman, Richard Saul. Access New York City. New York: HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN 0062772740

- ^ "Second Tammany Hall Building Proposed as Historic Landmark". Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ Allen, p. 259

- ^ "Redevelopment of old Tammany Hall marks latest changes in Union Square". Crain's New York Business. August 9, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Tammany Hall a Landmark Archived October 31, 2013, at the Wayback Machine New York Daily News

- ^ Young, Michael (July 11, 2020). "Tammany Hall Renovation and Expansion Nearing Completion at 44 Union Square". New York YIMBY. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Gut Renovation Turns Former Tammany Hall into Offices, Retail". Connect Media. July 31, 2020. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1990). The Authoritative Calvin and Hobbes. p. 10.

- ^ "Tammany Hall (2007)". BoardGameGeek. 30645. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

Works cited[edit]

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2005). Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York. Carroll & Graff.

- Allen, Oliver E. (1993). The Tiger: The Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0201624632.

- Burrows, Edwin G.; Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- Connable, Alfred; Silberfarb, Edward (1967). Tigers of Tammany: Nine Men Who Ran New York. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Czitrom, Daniel (1991). "Underworlds and Underdogs: Big Tim Sullivan and Metropolitan Politics in New York, 1889–1913". The Journal of American History. 78 (2): 536–558. doi:10.2307/2079533. JSTOR 2079533.

- Golway, Terry (2014). Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics. Liveright: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hooper, Franklin Henry (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Huthmacher, J. Joseph (1965). "Charles Evans Hughes and Charles Francis Murphy: The Metamorphosis of Progressivism". New York History. 46 (1): 25–40. JSTOR 23162464.

- Jackson, ed. (1996). Encyclopedia of New York City.

- Myers, Gustavus (1917). The History of Tammany Hall. Boni & Liveright. ISBN 9780722228463.

- Parmet, Herbert S.; Hecht, Marie B. (1967). Aaron Burr; Portrait of an Ambitious Man. New York, Macmillan.

- Riordan, William (1963). Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics. New York: E.P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0525471189.

- Shefter, Martin (1978). "The electoral foundations of the political machine: New York City, 1884–1897". In Silbey, Joey; Bogue, Allan G. (eds.). The history of American electoral behavior.

Further reading[edit]

- Colburn, David R.; Pozzetta, George E. (1976). "Bosses and Machines: Changing interpretations in American history". The History Teacher. 9 (3): 445–63. doi:10.2307/492336. JSTOR 492336.

- Cornwell, Elmer E. Jr. (1976). "Bosses, Machines, and Ethnic Groups". In Callow, Alexander B. Jr. (ed.). The City Boss in America: An Interpretive Reader. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Erie, Steven P (1988). Rainbow's End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of Urban Machine Politics, 1840–1985. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520061194.

- Finegold, Kenneth (1995). Experts and Politicians: Reform Challenges to Machine Politics in New York, Cleveland, and Chicago. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691037349. OCLC 30666095.

- Henderson, Thomas M. (1976). Tammany Hall and the New Immigrants: The Progressive Years. Ayer Company Publishers.

- Hershkowitz, Leo. Tweed's New York: Another Look. (New York: Anchor Press, 1977) online See also online review.

- Home, Rufus (April 1872). "The Story of Tammany, Part I: How It was Made a Political Power". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 44 (263): 685–96.

- Home, Rufus (May 1872). "The Story of Tammany, Part II: How It Grew to Political Supremacy". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 44 (264): 835–48.

- LaCerra, Charles (1997). Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Tammany Hall of New York. University Press of America.

- Lash, Joseph (1972). Eleanor: The Years Alone. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 274–76. ISBN 978-0393073614.

- Low, A. Maurice (1903). "Tammany Hall: Its Boss, Its Methods, and Its Meaning". In Norman, Henry (ed.). The World's Work, Volume II: June to November 1903. pp. 378–82.

- Lui, Adonica Y. (1995). "The Machine and Social Policies: Tammany Hall and the Politics of Public Outdoor Relief, New York City, 1874–1898". Studies in American Political Development. 9 (2): 386–403. doi:10.1017/S0898588X0000136X. ISSN 0898-588X. S2CID 145463525.

- Mandelbaum, Seymour Jacob (1965). Boss Tweed's New York. New York: Wiley Press. OCLC 925964624.

- Moscow, Warren (1971). The Last of the Big-Time Bosses: The Life and Times of Carmine de Sapio and the Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0812814002.

- Mushkat, Jerome (1990). Fernando Wood: A Political Biography. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0873384131.

- Sloat, Warren (2002). A Battle for the Soul of New York: Tammany Hall, Police Corruption, Vice, and Reverend Charles Parkhurst's Crusade against Them, 1892–1895. Cooper Square.

- Stave, Bruce M.; Allswang, John M.; McDonald, Terrence J.; Teaford, Jon C. (May 1988). "A Reassessment of the Urban Political Boss: An Exchange of Views". The History Teacher. 21 (3): 293–312. doi:10.2307/492997. JSTOR 492997.

- Steffens, Lincoln (1904). The Shame of the Cities. McClure, Philips, and Company.

- Stoddard, T. L. (1931). Master of Manhattan: The Life of Richard Croker. Longmans, Green and Company. OCLC 1535182.

- Thomas, Samuel J. (2004). "Mugwump Cartoonists, the Papacy, and Tammany Hall in America's Gilded Age". Religion and American Culture. 14 (2): 213–50. doi:10.1525/rac.2004.14.2.213. ISSN 1052-1151. S2CID 145410903.

- Walker, John C. (1989) The Harlem Fox: J. Raymond Jones at Tammany 1920:1970, New York: State University of New York Press.

- Weiss, Nancy Joan. (1968) Charles Francis Murphy, 1858-1924: Respectability and Responsibility in Tammany Politics. Smith College, 1968 online

- Werner, Morris Robert (1928). Tammany Hall. New York: Doubleday.