The War of the Worlds

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

1898 UK first edition | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | William Heinemann (UK) Harper & Bros (US) |

Publication date | 1898[1] |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 287 |

| Text | The War of the Worlds at Wikisource |

The War of the Worlds is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells, first serialised in 1897 by Pearson's Magazine in the UK and by Cosmopolitan magazine in the US. The novel's first appearance in hardcover was in 1898 from publisher William Heinemann of London. Written between 1895 and 1897,[2] it is one of the earliest stories to detail a conflict between mankind and an extra-terrestrial race.[3] The novel is the first-person narrative of both an unnamed protagonist in Surrey and of his younger brother in London as southern England is invaded by Martians. The novel is one of the most commented-on works in the science fiction canon.[4]

The book's plot was similar to numerous works of invasion literature which were published around the same period, and has been variously interpreted as a commentary on the theory of evolution, British colonialism, and Victorian-era fears, superstitions and prejudices. Wells later noted that an inspiration for the plot was the catastrophic effect of European colonisation on the Aboriginal Tasmanians; some historians have argued that Wells wrote the book in part to encourage his readership to question the morality of imperialism.[5] At the time of the book's publication, it was classified as a scientific romance, like Wells's earlier novel The Time Machine.

The War of the Worlds has been both popular (having never been out of print) and influential, spawning half a dozen feature films, radio dramas, a record album, various comic book adaptations, a number of television series, and sequels or parallel stories by other authors. It was memorably dramatised in a 1938 radio programme directed by and starring Orson Welles that allegedly caused public panic among listeners who did not know the book's events were fictional. The novel has even influenced the work of scientists, notably Robert H. Goddard, who, inspired by the book, helped develop both the liquid-fuelled rocket and multistage rocket, which resulted in the Apollo 11 Moon landing 71 years later.[6][7]

Plot

This section's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (November 2022) |

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own... Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

— H. G. Wells (1898), The War of the Worlds

The Coming of the Martians

The narrative opens by stating that as humans on Earth busied themselves with their own endeavours during the mid-1890s, aliens on Mars began plotting an invasion of Earth because their own resources are dwindling. The Narrator (who is unnamed throughout the novel) is invited to an astronomical observatory at Ottershaw where explosions are seen on the surface of the planet Mars, creating much interest in the scientific community. Months later, a so-called "meteor" lands on Horsell Common, near the Narrator's home in Woking, Surrey. He is among the first to discover that the object is an artificial cylinder that opens, disgorging Martians who are "big" and "greyish" with "oily brown skin", "the size, perhaps, of a bear", each with "two large dark-coloured eyes", and lipless "V-shaped mouths" which drip saliva and are surrounded by two "Gorgon groups of tentacles". The Narrator finds them "at once vital, intense, inhuman, crippled and monstrous".[8] They emerge briefly, but have difficulty in coping with the Earth's atmosphere and gravity, and so retreat rapidly into their cylinder.

A human deputation (which includes the astronomer Ogilvy) approaches the cylinder with a white flag, but the Martians incinerate them and others nearby with a heat-ray before beginning to assemble their machinery. Military forces arrive that night to surround the common, bringing with them field artillery and Maxim guns. The population of Woking and the surrounding villages are reassured by the presence of the British Army. A tense day begins, with much anticipation by the Narrator of military action.

After heavy firing from the common and damage to the town from the heat-ray which suddenly erupts in the late afternoon, the Narrator takes his wife to safety in nearby Leatherhead, where his cousin lives, using a rented, two-wheeled horse cart. He then returns to Woking to return the cart when in the early morning hours, a violent thunderstorm erupts. On the road during the height of the storm, he has his first terrifying sight of a fast-moving Martian fighting-machine; in a panic, he crashes the horse cart, barely escaping detection. He discovers the Martians have assembled towering three-legged "fighting-machines" (tripods), each armed with a heat-ray and a chemical weapon: the poisonous "black smoke". These tripods have wiped out the army units positioned around the cylinder and attacked and destroyed most of Woking. Taking shelter in his house, the Narrator sees a fleeing artilleryman moving through his garden, who later tells the Narrator of his experiences and mentions that another cylinder has landed between Woking and Leatherhead, which means the Narrator is now cut off from his wife. The two try to escape via Byfleet just after dawn, but are separated at the Shepperton to Weybridge Ferry during a Martian afternoon attack on Shepperton.

One of the Martian fighting-machines is brought down in the River Thames by artillery as the Narrator and countless others try to cross the river into Middlesex, and the Martians retreat to their original crater. This gives the authorities precious hours to form a defence-line covering London. After the Martians' temporary repulse, the Narrator is able to float down the Thames in a boat towards London, stopping at Walton, where he first encounters the curate, his companion for the coming weeks.

Towards dusk, the Martians renew their offensive, breaking through the defence-line of siege guns and field artillery centred on Richmond Hill and Kingston Hill by a widespread bombardment of the black smoke; an exodus of the population of London begins. This includes the Narrator's younger brother, a medical student (also unnamed), who flees to the Essex coast, after the sudden, panicked, pre-dawn order to evacuate London is given by the authorities, on a terrifying and harrowing journey of three days, amongst thousands of similar refugees streaming from London. The brother encounters Mrs. Elphinstone and her younger sister-in-law, just in time to help them fend off three men who are trying to rob them. Since Mrs. Elphinstone's husband is missing, the three continue on together.

After a terrifying struggle to cross a streaming mass of refugees on the road at Barnet, they head eastward. Two days later, at Chelmsford, their pony is confiscated for food by the local Committee of Public Supply. They press on to Tillingham and the sea. There, they manage to buy passage to Continental Europe on a small paddle steamer, part of a vast throng of shipping gathered off the Essex coast to evacuate refugees. The torpedo ram HMS Thunder Child destroys two attacking tripods before being destroyed by the Martians, although this allows the evacuation fleet to escape, including the ship carrying the Narrator's brother and his two travelling companions. Shortly thereafter, all organised resistance has collapsed, and the Martians roam the shattered landscape unhindered.

The Earth under the Martians

At the beginning of Book Two, the Narrator and the curate are plundering houses in search of food. During this excursion, the men witness a Martian handling-machine enter Kew, seizing any person it finds and tossing them into a "great metallic carrier which projected behind him, much as a workman's basket hangs over his shoulder",[9] and the Narrator realises that the Martian invaders may have "a purpose other than destruction" for their victims.[9] At a house in Sheen, "a blinding glare of green light" and a loud concussion attend the arrival of the fifth Martian cylinder,[9] and both men are trapped beneath the ruins for two weeks.

The Narrator's relations with the curate deteriorate over time, and eventually he knocks him unconscious to silence his now loud ranting; the curate is overheard outside by a Martian, which eventually removes his unconscious body with one of its handling machine tentacles. The reader is then led to believe the Martians will perform a fatal transfusion of the curate's blood to nourish themselves, as they have done with other captured victims viewed by the Narrator through a small slot in the house's ruins. The Narrator just barely escapes detection from the returned foraging tentacle by hiding in the adjacent coal-cellar.

Eventually the Martians abandon the cylinder's crater, and the Narrator emerges from the collapsed house where he had observed the Martians up close during his ordeal; he then approaches West London. Enroute, he finds the Martian red weed everywhere, a prickly vegetation spreading wherever there is abundant water but slowly dying due to bacterial infection. On Putney Heath, once again he encounters the artilleryman, who persuades him of a grandiose plan to rebuild civilisation by living underground; after a few hours, the Narrator perceives the laziness of his companion and abandons him. Now in a deserted and silent London, slowly he begins to go mad from his accumulated trauma, finally attempting to end it all by openly approaching a stationary fighting-machine. To his surprise, he discovers that all the Martians have been killed by an onslaught of earthly pathogens, to which they had no immunity: "slain, after all man's devices had failed, by the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this earth".[10]

The Narrator continues on, finally suffering a brief but complete nervous breakdown, which affects him for days; he is nursed back to health by a kind family. Eventually, he is able to return by train to Woking via a patchwork of newly repaired tracks. At his home, he discovers that his beloved wife has, somewhat miraculously, survived. In the last chapter, the Narrator reflects on the significance of the Martian invasion, its impact on humanity's view of itself and the future, and the "abiding sense of doubt and insecurity" it has left in his mind.

Style

The War of the Worlds presents itself as a factual account of the Martian invasion. It is considered one of the first works to theorise the existence of a race intelligent enough to invade Earth. The Narrator is a middle-class writer of philosophical papers, somewhat reminiscent of Doctor Kemp in The Invisible Man, with characteristics similar to author Wells at the time of writing. The reader learns very little about the background of the Narrator or indeed of anyone else in the novel; characterisation is unimportant. In fact none of the principal characters are named, aside from the astronomer Ogilvy.[11][failed verification]

Scientific setting

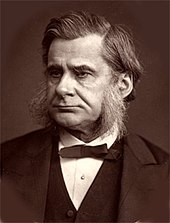

Wells trained as a science teacher during the latter half of the 1880s. One of his teachers was Thomas Henry Huxley, a major advocate of Darwinism. He later taught science, and his first book was a biology textbook. He joined the scientific journal Nature as a reviewer in 1894.[12][13] Much of his work is notable for making contemporary ideas of science and technology easily understandable to readers.[14]

The scientific fascinations of the novel are established in the opening chapter where the Narrator views Mars through a telescope, and Wells offers the image of the superior Martians having observed human affairs, as though watching tiny organisms through a microscope. Ironically it is microscopic Earth lifeforms that finally prove deadly to the Martian invasion force.[15][failed verification] In 1894 a French astronomer observed a 'strange light' on Mars, and published his findings in the scientific journal Nature on the second of August that year. Wells used this observation to open the novel, imagining these lights to be the launching of the Martian cylinders toward Earth.[citation needed]

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed geological features on Mars in 1878 which he called canali (Italian for "channels"). This concept was explored by American astronomer Percival Lowell in the book Mars in 1895, speculating that these might be irrigation channels constructed by a sentient life form to support existence on an arid, dying world, similar to that which Wells suggests the Martians have left behind.[11][16][failed verification] The novel also presents ideas related to Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, both in specific ideas discussed by the Narrator, and themes explored by the story.[citation needed]

Wells also wrote an essay titled 'Intelligence on Mars', published in 1896 in the Saturday Review, which sets out many of the ideas for the Martians and their planet that are used almost unchanged in The War of the Worlds.[11] In the essay he speculates about the nature of the Martian inhabitants and how their evolutionary progress might compare to humans. He also suggests that Mars, being an older world than the Earth, might have become frozen and desolate, conditions that might encourage the Martians to find another planet on which to settle.[17] Wells has also theorised how life could evolve in the conditions that are so hostile like those on Mars. The creatures have no digestive system, no appendages except tentacles and put the blood of other beings in their veins to survive. Wells was writing some years before 1901, when the Austrian Karl Landsteiner discovered the three human blood groups (O, A, and B), showing that even the blood of some humans can be lethal when introduced into the veins of other humans (if they belong to incompatible blood groups). But even before that discovery, it was clearly implausible that the blood of beings from one planet could be successfully introduced to the veins of creatures from another planet.[citation needed]

Physical location

In 1895, Wells was an established writer and he married his second wife, Catherine Robbins, moving with her to the town of Woking in Surrey. There, he spent his mornings walking or cycling in the surrounding countryside, and his afternoons writing. The original idea for The War of the Worlds came from his brother during one of these walks, pondering on what it might be like if alien beings were suddenly to descend on the scene and start attacking its inhabitants.[18]

Much of The War of the Worlds takes place around Woking and the surrounding area. The initial landing site of the Martian invasion force, Horsell Common, was an open area close to Wells' home. In the preface to the Atlantic edition of the novel, he wrote of his pleasure in riding a bicycle around the area, imagining the destruction of cottages and houses he saw by the Martian heat-ray or their red weed.[11] While writing the novel, Wells enjoyed shocking his friends by revealing details of the story, and how it was bringing total destruction to parts of the South London landscape that were familiar to them. The characters of the artilleryman, the curate, and the brother medical student were also based on acquaintances in Woking and Surrey.[19]

Wells wrote in a letter to Elizabeth Healey about his choice of locations: "I'm doing the dearest little serial for Pearson's new magazine, in which I completely wreck and sack Woking – killing my neighbours in painful and eccentric ways – then proceed via Kingston and Richmond to London, which I sack, selecting South Kensington for feats of peculiar atrocity."[20]

A 23 feet (7.0 m) high sculpture of a tripod fighting machine, entitled The Martian,[contradictory] based on descriptions in the novel stands in Crown Passage close to the local railway station in Woking, designed and constructed by artist Michael Condron.[21]

Cultural setting

Wells' depiction of late Victorian suburban culture in the novel was an accurate representation of his own experiences at the time of writing.[22] In the late 19th century, the British Empire was the predominant colonial power on the globe, making its domestic heart a poignant and terrifying starting point for an invasion by Martians with their own imperialist agenda.[23] He also drew upon a common fear which had emerged in the years approaching the turn of the century, known at the time as fin de siècle or 'end of the age', which anticipated an apocalypse occurring at midnight on the last day of 1899.[19][failed verification]

Publication

In the late 1890s it was common for novels, prior to full volume publication, to be serialised in magazines or newspapers, with each part of the serialisation ending upon a cliffhanger to entice audiences to buy the next edition. This is a practice familiar from the first publication of Charles Dickens' novels earlier in the nineteenth century. The War of the Worlds was first published in serial form in the United Kingdom in Pearson's Magazine in April – December 1897.[24] Wells was paid £200 and Pearsons demanded to know the ending of the piece before committing to publish.[25] The complete volume was first published by William Heinemann (of London publishing house Heinemann) in 1898 and has been in print ever since.[26]

Two unauthorised serialisations of the novel were published in the United States prior to the publication of the novel. The first was published in the New York Evening Journal between December 1897 and January 1898. The story was published as Fighters from Mars or the War of the Worlds. It changed the location of the story to a New York setting.[27] The second version changed the story to have the Martians landing in the area near and around Boston, and was published by The Boston Post in 1898, which Wells protested against. It was called Fighters from Mars, or the War of the Worlds in and near Boston.[12]

Both pirated versions of the story were followed by Edison's Conquest of Mars by Garrett P. Serviss. Even though these versions are deemed as unauthorised serialisations of the novel, it is possible that H. G. Wells may have, without realising it, agreed to the serialisation in the New York Evening Journal.[28][vague]

Holt, Rinehart & Winston repressed the book in 2000, paired with The Time Machine, and commissioned Michael Koelsch to illustrate a new cover art.[29]

Reception

The War of the Worlds was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. The Illustrated London News wrote that Wells' work had "a very distinct success" when serialised[clarification needed] in Pearson’s magazine.[30] The story did even better as a book, and reviewers rated it as "the very best work he has yet produced".[30] The book's London publisher Heinemann had a plentiful supply of positive reviews for use in promotions, with reviewers highlighting the story's originality in representing Mars in a new light through the concept of an alien invasion of Earth.[30]

Writing for Harper's Weekly, Sidney Brooks admired Wells' writing style: "he has complete check over his imagination, and makes it effective by turning his most horrible of fancies into the language of the simplest, least startling denomination".[30] Praising Wells' "power of vivid realization", The Daily News reviewer wrote, "the imagination, the extraordinary power of presentation, the moral significance of the book cannot be contested".[30] There was, however, some criticism of the brutal nature of the events in the narrative.[31]

Relation to invasion literature

Between 1871 and 1914 more than 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was The Battle of Dorking (1871) by George Tomkyns Chesney, an army officer. The book portrays a surprise German attack, with a landing on the south coast of England, made possible by the distraction of the Royal Navy in colonial patrols and the army in an Irish insurrection. The German army makes short work of English militia and rapidly marches to London. The story was published in Blackwood's Magazine in May 1871 and was so popular that it was reprinted a month later as a pamphlet which sold 80,000 copies.[32][33]

The appearance of this literature reflected the increasing feeling of anxiety and insecurity as international tensions between European Imperial powers escalated towards the outbreak of the First World War. Across the decades the nationality of the invaders tended to vary, according to the most acutely perceived threat at the time. In the 1870s the Germans were the most common invaders. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a period of strain on Anglo-French relations, and the signing of a treaty between France and Russia, caused the French to become the more common menace.[32][33]

There are a number of plot similarities between Wells's book and The Battle of Dorking. In both books a ruthless enemy makes a devastating surprise attack, with the British armed forces helpless to stop its relentless advance, and both involve the destruction of the Home Counties of southern England.[33] However The War of the Worlds transcends the typical fascination of invasion literature with European politics, the suitability of contemporary military technology to deal with the armed forces of other nations, and international disputes, with its introduction of an alien adversary.[34]

Although much of invasion literature may have been less sophisticated and visionary than Wells's novel, it was a useful, familiar genre to support the publication success of the piece, attracting readers used to such tales. It may also have proved an important foundation for Wells's ideas as he had never seen or fought in a war.[35]

Scientific predictions and accuracy

Mars

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo scientific ideas of the time, including Pierre-Simon Laplace's nebular hypothesis, Charles Darwin's scientific theory of natural selection, and Gustav Kirchhoff's theory of spectroscopy. These scientific ideas combined to present the possibility that planets are alike in composition and conditions for the development of species, which would likely lead to the emergence of life at a suitable geological age in a planet's development.[36]

By the time Wells wrote The War of the Worlds, there had been three centuries of observation of Mars through telescopes. Galileo observed the planet's phases in 1610 and in 1666 Giovanni Cassini identified the polar ice caps.[16] In 1878 Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed geological features which he called canali (Italian for "channels"). This was mistranslated into English as "canals" which, being artificial watercourses, fuelled the belief in intelligent extraterrestrial life on the planet. This further influenced American astronomer Percival Lowell.[37]

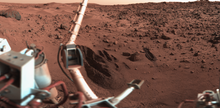

In 1895 Lowell published a book titled Mars, which speculated about an arid, dying landscape, whose inhabitants built canals to bring water from the polar caps to irrigate the remaining arable land. This formed the most advanced scientific ideas about the conditions on the red planet available to Wells at the time The War of the Worlds was written, but the concept was later proved erroneous by more accurate observation of the planet, and later landings by Russian and American probes such as the two Viking missions, that found a lifeless world too cold for water to exist in its liquid state.[16]

Space travel

The Martians travel to the Earth in cylinders, apparently fired from a huge space gun on the surface of Mars. This was a common representation of space travel in the nineteenth century, and had also been used by Jules Verne in From the Earth to the Moon. Modern scientific understanding renders this idea impractical, as it would be difficult to control the trajectory of the gun precisely, and the force of the explosion necessary to propel the cylinder from the Martian surface to the Earth would likely kill the occupants.[38]

However, the 16-year-old Robert H. Goddard was inspired by the story and spent much of his life building rockets.[6][7] The work of the German rocket scientists Hermann Oberth and his student Wernher von Braun led to the V-2 rocket becoming the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line on 20 June 1944,[39] and rocket developments culminated in the Apollo program's human landing on the Moon, and the landing of robotic probes on Mars.[40]

Total war

The Martian invasion's principal weapons are the Heat-Ray and the poisonous Black Smoke. Their strategy includes the destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways, and telegraph lines; it appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth century progressed, particularly during the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of surgical strikes on key military and civilian targets.[41]

Wells's vision of a war bringing total destruction without moral limitations in The War of the Worlds was not taken seriously by readers at the time of publication. He later expanded these ideas in the novels When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), The War in the Air (1908), and The World Set Free (1914). This kind of total war did not become fully realised until the Second World War.[42]

Critic Howard Black wrote that "In concrete details the Martian Fighting Machines as depicted by Wells have nothing in common with tanks or dive bombers, but the tactical and strategic use made of them is strikingly reminiscent of Blitzkrieg as it would be developed by the German armed forces four decades later. The description of the Martians advancing inexorably, at lightning speed, towards London; the British Army completely unable to put up an effective resistance; the British government disintegrating and evacuating the capital; the mass of terrified refugees clogging the roads, all were to be precisely enacted in real life at 1940 France." Black regarded this 1898 depiction as far closer to the actual land fighting of World War II than Wells's much later work The Shape of Things to Come (1933).[43]

Weapons and armour

Wells's description of chemical weapons – the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to kill human beings in great numbers – became a reality in World War I.[24] The comparison between lasers and the Heat-Ray was made as early as the later half of the 1950s when lasers were still in development. Prototypes of mobile laser weapons have been developed and are being researched and tested as a possible future weapon in space.[41]

Military theorists of the era, including those of the Royal Navy prior to the First World War, had speculated about building a "fighting-machine" or a "land dreadnought". Wells later further explored the ideas of an armoured fighting vehicle in his short story "The Land Ironclads".[44] There is a high level of science fiction abstraction in Wells's description of Martian automotive technology; he stresses how Martian machinery is devoid of wheels. They use "a complicated system of sliding parts" to produce movement, possess multiple whip-like tentacles for grasping, and paralleling animal motion, "quasi-muscles abounded in the crablike handling machine".[45]

Interpretations

Natural selection

H. G. Wells was a student of Thomas Henry Huxley, a proponent of the theory of natural selection.[46] In the novel, the conflict between mankind and the Martians is portrayed as a survival of the fittest, with the Martians whose longer period of successful evolution on the older Mars has led to them developing a superior intelligence, able to create weapons far in advance of humans on the younger planet Earth, who have not had the opportunity to develop sufficient intelligence to construct similar weapons.[46]

Human evolution

The novel also suggests a potential future for human evolution and perhaps a warning against overvaluing intelligence against more human qualities. The Narrator describes the Martians as having evolved an overdeveloped brain, which has left them with cumbersome bodies, with increased intelligence, but a diminished ability to use their emotions, something Wells attributes to bodily function.[citation needed]

The Narrator refers to an 1893 publication suggesting that the evolution of the human brain might outstrip the development of the body, and organs such as the stomach, nose, teeth, and hair would wither, leaving humans as thinking machines, needing mechanical devices much like the Tripod fighting machines, to be able to interact with their environment. This publication is probably Wells's own "The Man of the Year Million", first published in The Pall Mall Gazette on 6 November 1893, which suggests similar ideas.[47][48]

Colonialism and imperialism

At the time of the novel's publication the British Empire had conquered and colonised dozens of territories in Africa, Oceania, North and South America, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and the Atlantic and Pacific islands.

While invasion literature had provided an imaginative foundation for the idea of the heart of the British Empire being conquered by foreign forces, it was not until The War of the Worlds that the reading public was presented with an adversary completely superior to themselves.[49] A significant motivating force behind the success of the British Empire was its use of sophisticated technology; the Martians, also attempting to establish an empire on Earth, have technology superior to their British adversaries.[50] In The War of the Worlds, Wells depicted an imperial power as the victim of imperial aggression, and thus perhaps encouraging the reader to consider imperialism itself.[49]

Wells suggests this idea in the following passage:[according to whom?]

And before we judge them [the Martians] too harshly, we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished Bison and the Dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

— Chapter I, "The Eve of the War"

Social Darwinism

The novel also dramatises the ideas of race presented in Social Darwinism, in that the Martians exercise over humans their 'rights' as a superior race, more advanced in evolution.[51]

Social Darwinism suggested that the success of these different ethnic groups in world affairs, and social classes in a society, were the result of evolutionary struggle in which the group or class more fit to succeed did so; i.e., the ability of an ethnic group to dominate other ethnic groups or the chance to succeed or rise to the top of society was determined by genetic superiority. In more modern times it is typically seen as dubious and unscientific for its apparent use of Darwin's ideas to justify the position of the rich and powerful, or dominant ethnic groups.[52]

Wells himself matured in a society wherein the merit of an individual was not considered as important as their social class of origin. His father was a professional sportsman, which was seen as inferior to 'gentle' status; whereas his mother had been a domestic servant, and Wells himself was, prior to his writing career, apprenticed to a draper. Trained as a scientist, he was able to relate his experiences of struggle to Darwin's idea of a world of struggle; but perceived science as a rational system, which extended beyond traditional ideas of race, class and religious notions, and in fiction challenged the use of science to explain political and social norms of the day.[53]

Religion and science

Good and evil appear relative[according to whom?] in The War of the Worlds, and the defeat of the Martians has an entirely material cause: the action of microscopic bacteria. An insane clergyman is important in the novel, but his attempts to relate the invasion to Armageddon seem[according to whom?] examples of his mental derangement.[48] His death, as a result of his evangelical outbursts and ravings attracting the attention of the Martians, appears an indictment[according to whom?] of his obsolete religious attitudes;[54] but the Narrator twice prays to God, and suggests that bacteria may have been divinely allowed to exist on Earth for a reason such as this, suggesting a more nuanced critique.[citation needed]

Influences

Mars and Martians

The novel originated several enduring Martian tropes in science fiction writing. These include Mars being an ancient world, nearing the end of its life, being the home of a superior civilisation capable of advanced feats of science and engineering, and also being a source of invasion forces, keen to conquer the Earth. The first two tropes were prominent in Edgar Rice Burroughs's "Barsoom" series beginning with A Princess of Mars in 1912.[16][failed verification]

Influential scientist Freeman Dyson, a key figure in the search for extraterrestrial life, also acknowledged his debt to reading H. G. Wells's fictions as a child.[55]

The publication and reception of The War of the Worlds also established the vernacular term of 'martian' as a description for something offworldly or unknown.[56]

Aliens and alien invasion

Antecedents

Wells is credited with establishing several extraterrestrial themes which were later greatly expanded by science fiction writers in the 20th century, including first contact and war between planets and their differing species. There were, however, stories of aliens and alien invasion prior to publication of The War of the Worlds.[57]

In 1727 Jonathan Swift published Gulliver's Travels. The tale included a people who are obsessed with mathematics and more advanced than Europeans scientifically. They populate a floating island fortress called Laputa, 4½ miles in diameter, which uses its shadow to prevent sun and rain from reaching earthly nations over which it travels, ensuring they will pay tribute to the Laputians.[58]

Voltaire's Micromégas (1752) includes two beings from Saturn and Sirius who, though human in appearance, are of immense size and visit the Earth out of curiosity. At first the difference in scale between them and the peoples of Earth makes them think the planet is uninhabited. When they discover the haughty Earth-centric views of Earth philosophers, they are greatly amused by how important Earth beings think they are compared to greater beings in the universe such as themselves.[59]

In 1892 Robert Potter, an Australian clergyman, published The Germ Growers in London. It describes a covert invasion by aliens who take on the appearance of human beings and attempt to develop a virulent disease to assist in their plans for global conquest. It was not widely read, and consequently Wells's vastly more successful novel is generally credited as the seminal alien invasion story.[57]

The first science fiction to be set on Mars may be Across the Zodiac: The Story of a Wrecked Record (1880) by Percy Greg. It was a long-winded book concerned with a civil war on Mars. Another Mars novel, this time dealing with benevolent Martians coming to Earth to give humankind the benefit of their advanced knowledge, was published in 1897 by Kurd Lasswitz – Two Planets (Auf Zwei Planeten). It was not translated until 1971, and thus may not have influenced Wells, although it did depict a Mars influenced by the ideas of Percival Lowell.[60]

Other examples are Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet (1889), which took place on Mars, Gustavus W. Pope's Journey to Mars (1894), and Ellsworth Douglas's Pharaoh's Broker, in which the protagonist encounters an Egyptian civilisation on Mars which, while parallel to that of the Earth, has evolved somehow independently.[61]

Early examples of influence on science fiction

Wells had already proposed another outcome for the alien invasion story in The War of the Worlds. When the Narrator meets the artilleryman the second time, the artilleryman imagines a future where humanity, hiding underground in sewers and tunnels, conducts a guerrilla war, fighting against the Martians for generations to come, and eventually, after learning how to duplicate Martian weapon technology, destroys the invaders and takes back the Earth.[54]

Six weeks after publication of the novel, The Boston Post newspaper published another alien invasion story, an unauthorised sequel to The War of the Worlds, which turned the tables on the invaders. Edison's Conquest of Mars was written by Garrett P. Serviss, a now little remembered writer, who described the inventor Thomas Edison leading a counterattack against the invaders on their home soil.[24] Though this is actually a sequel to Fighters from Mars, a revised and unauthorised reprint of The War of the Worlds, they both were first printed in the Boston Post in 1898.[62] Lazar Lagin published Major Well Andyou in the USSR in 1962, an alternative view of events in The War of the Worlds from the viewpoint of a traitor.[63]

The War of the Worlds was reprinted in the United States in 1927, before the Golden Age of science fiction, by Hugo Gernsback in Amazing Stories. John W. Campbell, another key science fiction editor of the era, and periodic short story writer, published several alien invasion stories in the 1930s. Many well known science fiction writers were to follow, including Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Clifford D. Simak and Robert A. Heinlein with The Puppet Masters and John Wyndham with The Kraken Wakes.[27]

Later examples

The theme of alien invasion has remained popular to the present day and is frequently used in the plots of all forms of popular entertainment including movies, television, novels, comics and video games.

Alan Moore's graphic novel, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume II, retells the events in The War of the Worlds.[citation needed]

Tripods

The Tripods trilogy of books features a central theme of invasion by alien-controlled tripods.[citation needed]

Adaptations

The War of the Worlds has inspired seven films, as well as various radio dramas, comic-book adaptations, video games, a number of television series, and sequels or parallel stories by other authors. Most are set in different locations or eras to the original novel. Among the adaptations is the 1938 radio broadcast that was narrated and directed by Orson Welles. The first two-thirds of the 60-minute broadcast were presented as a series of news bulletins, often described as having led to outrage and panic by listeners who believed the events described in the program to be real.[64] In some versions of the event, up to a million people ran outside in terror.[65] Later critics, however, point out that the supposed panic was exaggerated by newspapers of the time, seeking to discredit radio as a source of news and information[66] or exploit racial stereotypes.[65] According to research by A. Brad Schwartz, fewer than 50 Americans seem to have fled outside in the wake of the broadcast, and it is not clear how many of them heard the broadcast directly.[65][67] In 1953 came the first theatrical film of The War of the Worlds, produced by George Pal, directed by Byron Haskin, and starring Gene Barry.[68]

In 1978 a best selling musical album of the story was produced by Jeff Wayne, with the voices of Richard Burton and David Essex.[69][70] Two later, somewhat different live concert musical versions, based on the original album, have since been mounted by Wayne and toured throughout the UK and Europe. These feature a performing image in 3D of Liam Neeson, alongside live guest performers. Both versions of this stage production have utilised live music, narration, lavish projected computer animation and graphics, pyrotechnics, and a large Martian fighting machine appears on stage and lights up and fires its Heat-Ray.[69][70]

On 30 October 1988, a slightly updated version of the script by Howard Koch, adapted and directed by David Ossman, was presented by WGBH Radio, Boston and broadcast on National Public Radio for the 50th anniversary of the original Orson Welles broadcast.[71] The cast included Jason Robards in Welles' role of 'Professor Pierson', Steve Allen, Douglas Edwards, Hector Elizondo and Rene Auberjonois. A Halloween-based special episode of Hey Arnold! was aired to parody The War of the Worlds; the costumes that the main characters wore referenced a species from Star Trek. An animated series of Justice League from 2001 begins with a three-part saga called "Secret Origins" and features tripod machines invading and attacking the city.[citation needed]

Steven Spielberg directed a 2005 film adaptation starring Tom Cruise, which received generally positive reviews.[72][73] The Great Martian War 1913–1917 is a 2013 made-for-television science fiction film docudrama that adapts The War of the Worlds and unfolds in the style of a documentary broadcast on The History Channel. The film portrays an alternative history of World War I in which Europe and its allies, including America, fight the Martian invaders instead of Germany and its allies. The docudrama includes both new and digitally altered film footage shot during the War to End All Wars to establish the scope of the interplanetary conflict. The film's original 2013 UK broadcast was during the first year of the First World War centennial; the first US cable TV broadcast came in 2014, almost 10 months later.[citation needed]

In the spring of 2017, the BBC announced that in 2018 it would be producing an Edwardian period, three-episode mini-series adaptation of Wells novel. The first of the three episodes debuted in the UK on 17 November 2019.[74] Also in 2019, Fox debuted a series adaptation set in present-day Europe starring Gabriel Byrne and Elizabeth McGovern.[75]

Colin Morgan starred in The Coming of the Martians, a faithful audio dramatisation of Wells's 1897 novel, adapted by Nick Scovell, directed by Lisa Bowerman and produced in native 5.1 surround sound. It was released in July 2018 by Sherwood Sound Studios in download format and as a 2-Disc CD, a Limited Edition DVD.[76]

See also

- Deus ex machina

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

- The Space Machine

- The Second Invasion from Mars

- The Massacre of Mankind — an authorised sequel

References

Citations

- ^ Facsimile of the original 1st edition

- ^ David Y. Hughes and Harry M. Geduld, A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: H.G. Wells's Scientific Romance (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993), p. 1.

- ^ John L. Flynn (2005). "War of the Worlds: From Wells to Spielberg". p.5

- ^ Patrick Parrinder (2000). "Learning from Other Worlds: Estrangement, Cognition, and the Politics of Science Fiction and Utopia". P.132. Liverpool University Press

- ^ Ball, Philip (18 July 2018). "What the War of the Worlds means now". New Statesman. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Genesis: Search for Origins" (PDF). NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Robert Goddard and His Rockets". NASA.

- ^ Wells, The War of the Worlds, Book One, Ch. 4.

- ^ a b c Wells, The War of the Worlds, Book Two, Ch. 1.

- ^ Wells, The War of the Worlds, Book Two, Ch. 8.

- ^ a b c d Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-521-27804-X.

- ^ a b Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-415-15910-5.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1981). The Science Fiction of H.G. Wells. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-19-502812-0.

- ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. p. 239. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-521-27804-X.

- ^ a b c d Baxter, Stephen (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "H.G. Wells' Enduring Mythos of Mars". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 186–7. ISBN 1-932100-55-5.

- ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. p. 240. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ Martin, Christopher (1988). H.G. Wells. Wayland. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1-85210-489-9.

- ^ a b Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Spielberg. Galactic Books. pp. 12–19. ISBN 0-9769400-0-0.

- ^ Welles or Wells: The First Invasion from Mars Archived 24 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Phil Klass, The New York Times Review of Books, 1988

- ^ Pearson, Lynn F. (2006). Public Art Since 1950. Osprey Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 0-7478-0642-X.

- ^ Lackey, Mercedes (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "In Woking's Image". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 216. ISBN 1-932100-55-5.

- ^ Franklin, H. Bruce (2008). War Stars. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55849-651-4.

- ^ a b c Gerrold, David (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "War of the Worlds". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 202–205. ISBN 9781932100556.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 0-415-15910-5.

- ^ "The War of the Worlds". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ a b Urbanski, Heather (2007). Plagues, Apocalypses and Bug-Eyed Monsters. McFarland. pp. 156–8. ISBN 978-0-7864-2916-5.

- ^ David Y. Hughes and Harry M. Geduld, A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: H.G. Wells's Scientific Romance (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993), pgs 281–289.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (Herbert George) (2000). The time machine ; and, The war of the worlds. Internet Archive. Austin, TX : Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-056476-5.

- ^ a b c d e Beck, Peter J. (2016). The War of the Worlds: From H. G. Wells to Orson Welles, Jeff Wayne, Steven Spielberg and Beyond. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 143, 144.

- ^ Aldiss, Brian W.; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree: the History of Science Fiction. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 123. ISBN 0-575-03943-4.

- ^ a b Eby, Cecil D. (1988). The Road to Armageddon: The Martial Spirit in English Popular Literature, 1870–1914. Duke University Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 0-8223-0775-8.

- ^ a b c Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. CUP Archive. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-27804-X.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (2000). Learning from Other Worlds. Liverpool University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-85323-584-8.

- ^ McConnell, Frank (1981). The Science Fiction of H.G. Wells. Oxford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-19-502812-0.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 368–9. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Seed, David (2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Publishing. p. 546. ISBN 1-4051-1218-2.

- ^ Meadows, Arthur Jack (2007). The Future of the Universe. Springer. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85233-946-3.

- ^ Neufeld, 1995 pp 158, 160–162, 190

- ^ Society, National Geographic (15 September 2009). "Mars Exploration, Mars Rovers Information, Facts, News, Photos – National Geographic". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ a b Gannon, Charles E. (2005). Rumours of War and Infernal Machines. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0-7425-4035-9.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-415-15910-5.

- ^ Howard D. Black. Real and Imagined Wars and Armies. Jane Field (editor).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Landships: Armored Vehicles for Colonial-era Gaming". Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2006.

- ^ Wells, H. G.; Yeffeth, Glenn (2005). The War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic. BenBella Books. p. 113.

- ^ a b Williamson, Jack (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "The Evolution of the Martians". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBella: 189–195. ISBN 9781932100556.

- ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. pp. 129–131. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ a b Draper, Michael (1987). H.G. Wells. Macmillan. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-333-40747-4.

- ^ a b Zebrowski, George (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "The Fear of the Worlds". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 235–41. ISBN 1-932100-55-5.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 148. ISBN 0-333-97022-5.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (2000). Learning from Other Worlds. Liverpool University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-85323-584-8.

- ^ McClellan, James Edward; Dorn, Harold (2006). Science and Technology in World History. JHU Press. pp. 378–90. ISBN 0-8018-8360-1.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–44. ISBN 0-333-97022-5.

- ^ a b Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-521-27804-X.

- ^ Basalla, George (2006). Civilized Life in the Universe: Scientists on Intelligent Extraterrestrials. Oxford University Press US. p. 91. ISBN 9780195171815.

- ^ Silverberg, Robert (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "Introduction". War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H.G. Wells Classic/ Edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 12. ISBN 1-932100-55-5.

- ^ a b Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Spielberg. Galactic Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-9769400-0-0.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 301–304. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Hotakainen, Markus (2008). Mars: A Myth Turned to Landscape. Springer. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-387-76507-5.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2000). Space and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Groups. p. 38. ISBN 0-313-30846-2.

- ^ Edison's Conquest of Mars, "Foreword" by Robert Godwin, Apogee Books 2005

- ^ Schwartz, Matthias; Weller, Nina; Winkel, Heike (202). After Memory: World War II in Contemporary Eastern European Literatures. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 179.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (2010). "Chapter 23 – The Great Depression". The Unfinished Nation. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-07-338552-5.

- ^ a b c Jefferson Pooley; Michael J. Socolow (30 October 2018). "When historians traffic in fake news. Unraveling the myth of "War of the Worlds."". Washington Post.

- ^ Pooley, Jefferson (29 October 2013). "The Myth of the 'War of the Worlds' Panic". Slate. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Schwartz, A. Brad (2015). Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News (1st ed.). New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-3161-0.

- ^ "'The War of the Worlds'." British Board of Film Classification, 9 March 1953. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ a b Burrows, Alex (26 September 2020). "The story behind Jeff Wayne's The War Of The Worlds". Louder. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b Jones, Josh (30 March 2017). "Hear the Prog-Rock Adaptation of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds: The 1978 Rock Opera That Sold 15 Million Copies Worldwide". Open Culture. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ McDougal, Donald (15 September 1988). "50th-Anniversary 'War of the Worlds' to Air on NPR". The Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "War of the Worlds". Metacritic. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "War of the Worlds". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Nicholson, Rebecca (17 November 2019). "The War of the Worlds review – doom, dystopia and a dash of Downton". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (29 January 2019). "'War Of The Worlds': Gabriel Byrne & Elizabeth McGovern Lead Cast In Sci-Fi Series From Canal+, FNG & AGC". Deadline. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "The Coming of the Martians". Starburst magazine. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

Bibliography

- Coren, Michael (1993) The Invisible Man : The Life and Liberties of H.G. Wells. Publisher: Random House of Canada. ISBN 0-394-22252-0

- Gosling, John. Waging the War of the Worlds. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 2009. Paperback, ISBN 0-7864-4105-4.

- Hughes, David Y. and Harry M. Geduld, A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: H.G. Wells's Scientific Romance. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-253-32853-5

- Roth, Christopher F. (2005) "Ufology as Anthropology: Race, Extraterrestrials, and the Occult." In E.T. Culture: Anthropology in Outerspaces, ed. by Debbora Battaglia. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

- Yeffeth, Glenn (Editor) (2005) The War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic. Publisher: Benbella Books. ISBN 1-932100-55-5

External links

- The War of the Worlds Invasion, large resource containing comment and review on the history of The War of the Worlds

- The War of the Worlds at Standard Ebooks

- The War of the Worlds at Project Gutenberg.

The War of the Worlds public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The War of the Worlds public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Time Archives, a look at perceptions of The War of the Worlds over time

- Hundreds of cover images of the book's different editions, from 1898 to now

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from November 2022

- The War of the Worlds

- 1898 British novels

- 1898 science fiction novels

- Alien invasions in novels

- War of the Worlds written fiction

- Novels by H. G. Wells

- Novels first published in serial form

- Works originally published in Pearson's Magazine

- Novels set in Surrey

- Heinemann (publisher) books

- Novels adapted into comics

- British novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into plays

- Novels about extraterrestrial life

- Novels adapted into radio programs

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Novels adapted into video games

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- Harper & Brothers books

- Books with cover art by Michael Koelsch