Calgary Stampede: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

No edit summary |

rvv (aaaah! Rhinos!) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

The '''Calgary Stampede''' is an annual [[rodeo]], [[fair|exhibition]] and [[festival]] held every July in [[Calgary]], Alberta, Canada. The ten-day event, which bills itself as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth",<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/story/2008/07/04/stampede-parade.html |title=Yahoo! Stampede parade kicks off 'greatest outdoor show on earth' |publisher=Canadian Broadcasting Corporation |date=2008-07-04 |accessdate=2011-07-09}}</ref> attracts over one million visitors per year and features the world's largest rodeo, a [[parade]], [[Midway (fair)|midway]], [[stage show]]s, [[concert]]s, agricultural competitions, [[chuckwagon racing]] and [[First Nations]] exhibitions. |

The '''Calgary Stampede''' is an annual [[rodeo]], [[fair|exhibition]] and [[festival]] held every July in [[Calgary]], Alberta, Canada. The ten-day event, which bills itself as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth",<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/story/2008/07/04/stampede-parade.html |title=Yahoo! Stampede parade kicks off 'greatest outdoor show on earth' |publisher=Canadian Broadcasting Corporation |date=2008-07-04 |accessdate=2011-07-09}}</ref> attracts over one million visitors per year and features the world's largest rodeo, a [[parade]], [[Midway (fair)|midway]], [[stage show]]s, [[concert]]s, agricultural competitions, [[chuckwagon racing]] and [[First Nations]] exhibitions. |

||

The event's roots are traced to 1886 when the Calgary and District Agricultural Society held its first fair |

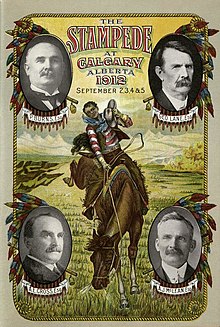

The event's roots are traced to 1886 when the Calgary and District Agricultural Society held its first fair. American promoter [[Guy Weadick]] launched his first rodeo in 1912 and returned to Calgary in 1919 to organize the Victory Stampede to honour soldiers returning from World War I. It became an annual event in 1923 when it merged with the Calgary Industrial Exhibition to create the '''Calgary Exhibition and Stampede'''. |

||

Organized by thousands of volunteers and supported by civic leaders, the Calgary Stampede has grown over the years into one of the world's richest rodeos and a significant tourist attraction for the city. Rodeo and chuckwagon racing events are televised across Canada. However, the rodeo, chuckwagon races and some other activities have been criticized in recent years by [[animal welfare]] groups concerned about particular events as well as [[animal rights]] groups seeking to ban rodeo in general. |

Organized by thousands of volunteers and supported by civic leaders, the Calgary Stampede has grown over the years into one of the world's richest rodeos and a significant tourist attraction for the city. Rodeo and chuckwagon racing events are televised across Canada. However, the rodeo, chuckwagon races and some other activities have been criticized in recent years by [[animal welfare]] groups concerned about particular events as well as [[animal rights]] groups seeking to ban rodeo in general. |

||

Revision as of 14:21, 15 July 2011

| Calgary Stampede | |

|---|---|

| A stylized wordmark saying "Calgary Stampede" below a C lazy-S logo. | |

Bareback bronc rider at the Stampede rodeo | |

| Genre | Rodeo and fair |

| Dates | July 8–17, 2011 |

| Location(s) | Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

| Founded | 1886 (Exhibition) 1912 (Stampede) |

| Attendance | 1,145,394 (2010)[1] 1,262,518 (record – 2006) |

| Website | Calgary Stampede |

The Calgary Stampede is an annual rodeo, exhibition and festival held every July in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The ten-day event, which bills itself as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth",[2] attracts over one million visitors per year and features the world's largest rodeo, a parade, midway, stage shows, concerts, agricultural competitions, chuckwagon racing and First Nations exhibitions.

The event's roots are traced to 1886 when the Calgary and District Agricultural Society held its first fair. American promoter Guy Weadick launched his first rodeo in 1912 and returned to Calgary in 1919 to organize the Victory Stampede to honour soldiers returning from World War I. It became an annual event in 1923 when it merged with the Calgary Industrial Exhibition to create the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede.

Organized by thousands of volunteers and supported by civic leaders, the Calgary Stampede has grown over the years into one of the world's richest rodeos and a significant tourist attraction for the city. Rodeo and chuckwagon racing events are televised across Canada. However, the rodeo, chuckwagon races and some other activities have been criticized in recent years by animal welfare groups concerned about particular events as well as animal rights groups seeking to ban rodeo in general.

Calgary's national and international identity is tied to the event. It is known as the "Stampede City", carries the informal nickname of "Cowtown" and the local Canadian Football League team is known as the Stampeders. The city takes on a party atmosphere during Stampede: office buildings and storefronts are painted in cowboy themes, residents don western wear and events held across the city include hundreds of pancake breakfasts and barbecues.

History

The Calgary and District Agricultural Society was formed in 1884 to promote the town and encourage farmers and ranchers from eastern Canada to move west. The society held its first fair two years later, attracting a quarter of the town's 2,000 residents.[3] By 1889, it had acquired land on the banks of the Elbow River to host the exhibitions but crop failures, poor weather and a declining economy resulted in the society ceasing operations in 1895.[4] The land passed briefly to future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett who sold it to the city. Naming the area Victoria Park after Queen Victoria, the city leased the land to the newly formed Western Pacific Exhibition Company which introduced a new agricultural and industrial fair in 1899.[5]

The exhibition grew annually, and in 1908, the Government of Canada announced that Calgary would host the federally funded Dominion Exhibition that year. Seeking to take advantage of the opportunity to promote itself, the city spent C$145,000 to build six new pavilions and a racetrack,[6] held a lavish parade and rodeo, horse racing and trick roping competitions as part of the event.[3] The exhibition was a success, drawing 100,000 people to the fairgrounds over seven days despite an economic recession that afflicted the city of 25,000.[6]

Guy Weadick, an American trick roper who participated in the Dominion Exhibition as part of the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Real Wild West Show, was drawn back to Calgary in 1912 in the hopes of establishing an event that more closely represented the "wild west" than the shows he was a part of.[7] With the assistance of local livestock agent H.C. McMullen, Weadick convinced businessmen Pat Burns, George Lane, A. J. MacLean, and A. E. Cross to put up $100,000 to guarantee funding for the event.[3] The Big Four, as they came to be known, viewed the proposed project as a celebration of their life as cattlemen.[8] The city built a rodeo arena on the fairgrounds and over 100,000 people attended the six-day event in September 1912 to watch hundreds of cowboys from Western Canada, the United States and Mexico compete for $20,000 in prizes.[9] The event made $120,000 and was hailed as a success. The city was nonetheless not convinced of the viability of the rodeo and it was not held again until 1919 when Weadick was invited to organize the Calgary Victory Stampede to celebrate the city's soldiers returning from World War I.[3]

Calgary Exhibition and Stampede

The Calgary Industrial Exhibition continued its annual fair but faced declining attendance into the 1920s. In 1922, it approached Weadick and suggested he join his Stampede with the fair. Weadick agreed, and the union created the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede.[10] The combined event was first held in 1923 and Weadick encouraged the city's residents to dress in western clothes and decorate their businesses in the spirit of the wild west.[3] Civic leaders truly supported the event for the first time; Mayor George Webster followed the suggestion to dress western and allowed downtown roads to be closed for two hours each morning of the six-day event to accommodate street parties.[10] The new sport of chuckwagon racing was also introduced in 1923 and proved immediately popular.[11] 138,950 people attended and the event earned a profit.[10] Over 167,000 people attended in 1924 and the success guaranteed that the Stampede and Exhibition would be held together permanently.[12]

The 1925 silent movie The Calgary Stampede used footage from the rodeo, exposing people across North America to the event. It was the first of at least five movies filmed during the Stampede by 1950.[13] Attendance suffered during the Great Depression but rebounded during World War II. While Toronto's Canadian National Exhibition ceased operations during the war, the Stampede remained active and offered the public an escape. Attendance had grown to 240,000 by 1939 – three times the population of Calgary.[12] Hollywood stars and foreign dignitaries were attracted to the Stampede. Bob Hope and Bing Crosby each served as parade marshals during the 1950s,[14] while Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip made their first of two visits to the event as part of their 1959 tour of Canada.[15] The Queen also opened the 1973 Stampede.[16]

Expansion

The discovery of the Leduc No. 1 oil well in 1946 along with major reserves in the Turner Valley area ushered in a period of great growth and prosperity. Calgary was transformed from an agricultural community into the oil and gas capital of Canada.[17] The city's population nearly doubled between 1949 and 1956, and Calgary's immigrant population not only embraced the Stampede, but encouraged their friends and family in their home towns to do the same.[17] The 1950s represented the golden age of the Calgary Stampede.[18]

Attendance records were broken nearly every year in the 1950s; overall attendance increased by 200,000 from 1949 to 1959.[19] The growth necessitated expansion of the exhibition grounds.[16] The 7,500 seat Stampede Corral was completed in 1950 as the largest indoor arena in Western Canada.[20] It housed the Calgary Stampeders hockey team, which was operated by the Board of Governors and won the Western Hockey League championship in 1954.[21] Acts such as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and Louis Armstrong played the Corral, however the arena's poor acoustics were a frequent concern to organizers and patrons.[22]

Improvements were made to the grandstand and the race track was rebuilt in 1954.[23] The Big Four Building, named in honour of the Stampede's founders, opened in 1959 to serve as the city's largest exhibition hall in the summer,[14] and was converted into a 24-sheet curling facility each winter.[23] The improvements failed to alleviate all the pressures growth had caused; chronic parking shortages and inability to accommodate demand for tickets to the rodeo and grandstand shows continued.[23]

Attendance continued to grow throughout the 1960s and 1970s, topping 500,000 for the first time in 1962 and reaching 654,000 in 1966, prompting organizers to expand the event from six days to nine in 1967 and then to ten one year later.[16] One million people attended for the first time in 1976.[3] The park, meanwhile, continued to grow. The Round-Up Centre opened in 1979 as the new exhibition hall, and the Olympic Saddledome was completed in 1983.[24] The Saddledome replaced the Corral as the city's top sporting arena, while both facilities hosted hockey and figure skating events at the 1988 Winter Olympics.[24]

Maintaining the traditional focus on agriculture and western heritage remained a priority for the Calgary Stampede as the city grew into a major financial and oil hub in Western Canada.[24] Aggie Days was introduced in 1989 as a means to introduce urban schoolchildren to agriculture and proved immediately popular.[24] A ten-year expansion plan called Horizon 2000 was released in 1990 detailing plans to grow Stampede Park into a year-round destination for Calgarians,[3] while an updated plan was released in 2004.[25] Attendance plateaued around 1.2 million since 2000, with the current record of 1,262,518 set in 2006.[26]

Stampede Park

Stampede Park is located southeast of downtown Calgary in the Beltline District and is serviced by Calgary Transit's light rail system. Permanent structures at the site include the Saddledome and Corral, The Big Four Building, The BMO Centre – a convention and exhibition facility – a casino, the Stampede Grandstand, the agriculture building, and a number of facilities that support the exhibition and livestock shows.[27]

The park remains at its original location, though attempts had been made in the past to relocate. In 1964, the Stampede Board attempted to purchase former military land in southwest Calgary near Glenmore Trail and 24 Street and relocate the park there. A fully developed plan was released in 1965, and while it had the support of the civic and federal governments, intense opposition from nearby residents quashed the plan.[28] Space concerns remained a constant concern, and plans to push northward into the Victoria Park community beginning in 1968 initiated a series of conflicts with the neighbourhood and city council.[29]

While Victoria Park fell into steady decline, it was not until 2007 that the final buildings were removed, paving the way for both an expansion of Stampede Park and an urban renewal program for the area.[30] With the land finally secured, the Stampede organization embarked on a $400-million expansion that is planned to feature a new retail and entertainment district, urban park, a new agricultural arena and potentially a new hotel. The expansion was originally planned to be complete by 2011, but delays and an economic downturn have pushed the expected completion of the project back to 2014.[31]

The Stampede Park has long been a central gathering place for Calgarians and tourists. In addition to attendance at the Calgary Stampede, over 2.5 million people attend other sporting events, concerts, trade shows and meetings on a grounds that hosts over 1,000 events annually.[32]

Events

Parade

The parade serves as the official opening of Stampede and begins shortly before 9 AM on the first Friday of the event.[33] Each year features a different parade marshal, chosen to reflect the public's interests at that time. Politicians, athletes, actors and other dignitaries have led the event over the years.[34] The event features dozens of marching bands, over 150 floats and hundreds of horses with entrants from around the world,[33][35] and combines western themes with modern. Cowboys, First Nations dancers, members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in their red serges are joined by clowns, bands, political and business leaders.[36] The first Stampede Parade in 1912 was attended by 75,000 people, greater than the city's population at the time.[37] As many as 350,000 people attended the parade in 2009,[33] while the presence of Prince William and Catherine, Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, at the 2011 parade as part of their tour of Canada increased attendance to a record estimate of 425,000.[38]

Rodeo

The rodeo is the heart of the Calgary Stampede.[39] It is the largest,[40] and most famous event of its kind in the world.[41] Offering a prize of $100,000 to the winner of each major discipline and $1,000,000 total on championship day alone, it also offers the richest payout in the world.[42] Cowboys consider performing in front of over 20,000 fans daily to be the highlight of the rodeo season.[39]

There are six major disciplines – bull riding, barrel racing, steer wrestling, tie down roping, saddle bronc and bareback riding – and four novice events – junior steer riding, novice bareback, novice saddle bronc and wild pony racing.[43] Each event is organized as its own tournament, and the cowboys and girls are divided into two pools. The first pool competes each night for the first four nights, and the second each night for four nights following. The top four in each pool advance to the Sunday final, and the remainder compete on Saturday for a wild card spot into the final. The competitor with the best time or score on Sunday wins the $100,000 grand prize.[44]

All livestock for the rodeo events come from the 22,000 acre Stampede Ranch located near the town of Hanna.[45] The ranch was created in 1961 as a means to improve the quality of bucking horses and bulls and to guarantee supply.[46] The first of its kind in North America,[45] the Stampede Ranch operates a breeding program that produces some of the top rodeo stock in the world.[47]

Rodeo events are broadcast nationally by the Canadian Broadcast Corporation (CBC) on its main network as well as its specialty channel, Bold.[48]

Rangeland Derby

Weadick is credited with inventing the sport of chuckwagon racing in 1923, inspired either by seeing a similar event in 1922 at the Gleichen Stampede or watching impromptu races as he grew up.[49] As it was the first year the Exhibition and Stampede were held together, Weadick wanted to add a new and exciting event.[50] He invited ranchers to enter their chuckwagons and crews to compete for a total of $275 in prize money.[51]

Named the Rangeland Derby, and nicknamed the "half-mile of hell",[52] chuckwagon racing proved immediately popular, and quickly became the event's largest attraction.[50] While only six teams raced in 1923,[53] today's Rangeland Derby consists of 36 teams competing for $1.15 million in prize money.[54] Races are broadcast nationally by the CBC.[55]

Prior to each year's Rangeland Derby, drivers auction advertising space on their wagons. The first advertisement on the tarp cover of a chuckwagon was made in 1941, and Lloyd Nelson was the last person to win the Rangeland Derby without a sponsored wagon in 1956. The current practice of selling advertising via a tarp auction began 1979.[56] The revenue generated by the auctions, over $2 million for the 2010 Stampede,[57] is considered an indicator of the strength of Calgary's economy.[58]

Exhibition

When the agricultural exhibition was first launched in 1886, Alberta was an overwhelmingly rural province. Today, agricultural producers make less than two percent of the province's population, but the exhibition remains an integral part of the Calgary Stampede.[59] Nearly half of all visitors attend the 50 agricultural programs that are organized by more than 1,000 exhibitors.[60] Numerous competitions are held as part of the exhibition. The National Cutting Horse Association sanctions a World Series of Cutting event,[61] and the World Championship Blacksmith Competition attracts top blacksmiths from around the world.[60] Farm and ranch demonstrations feature numerous breeds of livestock along with stock dog trials and team penning competitions.[62]

Additionally, the exhibition serves to educate the public about Alberta's ranching and agricultural heritage along with modern food production displays through events like Ag-tivity in the City.[63] The Stampede works with Alberta 4-H clubs to encourage youth participation in agricultural pursuits,[64] and has a partnership with Olds College that includes the operation of a satellite campus at Stampede Park.[65]

Midway

The Calgary Stampede midway has been operated by North American Midway Entertainment, and its predecessor, Conklin Shows, since 1976.[66] The midway is the only part of the event operated on a for-profit basis.[67] It is considered an essential component of the Stampede, but exists separate of the western themes that dominate all other aspects.[68] The midway opens on the Thursday night before other events begin, known as "sneak-a-peek" night.[69] In addition to the traditional rides and carnival games, the midway features two concert areas: the Coca-Cola Stage and Nashville North, which feature rock/pop and country music respectively, and draw acts from all over North America.[70][71]

Market

The Stampede Market is located in the BMO Centre on the northwest corner of the park.[27] It offers 38,000 square metres (410,000 sq ft) of retail space and in 2011 had 181 vendors selling artwork, toys, household goods foodstuffs and other items.[72] A subsection of the market, called the Western Oasis, offers cowboy and western themed artwork, bronze statues, craftwork, foods and wine.[27] Lured by the opportunity to show their wares to the one million people who attend the Stampede, some vendors wait years before gaining admittance, and those that do consider it one of the prime events of the year.[72]

People

Native participation

First Nations peoples had been frequent participants of the Calgary Industrial Exhibition since it was first held in 1886, participating in parades, sporting events and entertaining spectators with traditional dances. By 1912 however, pressure from agents of the Department of Indian Affairs to suppress their historic traditions and to keep them on their farms nearly ended native participation at the Exhibition.[73] Weadick hoped to include native people as a feature of his Stampede, but Indian Affairs opposed his efforts and asked the Duke of Connaught, Canada's Governor General, to support their position. The Duke refused, and after Weadick gained the support of political contacts in Ottawa, including future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, the path was cleared for participation by First Nations people.[74]

Six Indian tribes originally were active participants at the Calgary Stampede. Hundreds of native people attended, camping in teepees, wearing their finest traditional regalia and they are among the most popular participants in the parade.[74] Tom Three Persons, of the Blood Tribe, emerged as one of the Stampede's first heroes, amazing spectators with a winning performance in the saddle bronc competition.[3] Though Indian Affairs again unsuccessfully sought to ban native participation in 1925, the effort was unsuccessful,[75] and native people have remained an important part of the event since.

At each Stampede, the five nations of the Treaty 7 – the Tsuu T'ina, Piikani, Stoney, Kainai and Siksika – erect an Indian village on the bank of the Elbow River in the southern section of Stampede Park. They erect teepees, organize pow wows, offer arts and crafts and re-enact elements of their traditional lifestyle.[76] Each year, an Indian Princess is selected from one of the five nations to represent the Treaty 7 as part of the Stampede's royalty.[77]

Young Canadians and the Stampede Showband

When the Calgary Stampede brought The Rockettes in from New York as part of the 1964 grandstand show, they auditioned local youth to join a part of the show as the "Calgary Kidettes". It was intended to be a one-time addition, but proved immensely popular with spectators,[78] and both The Rockettes and the Kidettes returned in the following years.[79] The Kidettes were renamed the Young Canadians in 1968 and not only remained a staple of the Grandstand Show, but grew into a headlining act by the late 1970s.[78] Within nine years of their creation, the Young Canadians were playing shows throughout Canada and the northern United States and performed in front of over 200,000 people every year.[80] In 1982, the Stampede set up the Young Canadians School of Performing Arts. Supported by both the Calgary public and Catholic school boards, the school offers professional training to singers and dancers between the ages of 7 and 19 paid for by scholarships from the Stampede organization.[81]

The Stampede Showband was created in 1971 to serve as the organization's musical ambassadors. The troupe features over 150 members between the ages of 16 and 21, and have twice been named the world champion of marching show bands.[82] The group has performed all over the world, in front of royalty and world leaders,[82] and at the opening ceremonies of the 1988 Winter Olympics.[83] The Showband performs year round, and make over 100 appearances during the Stampede alone.[82] They will perform in the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California for the third time in 2012 as part of the Stampede's 100th anniversary celebrations.[84] The Stampede Showriders were created in 1985 as a precision equestrian drill team and colour guard that accompanies the Showband.[82]

Employment and volunteerism

Operating the 10-day event requires the coordination of thousands of employees and volunteers. The Stampede employs 300 full-time and 1,400 part-time staff throughout the year. In addition, over 3,500 seasonal employees are hired to run the event itself.[85] The seasonal positions are often filled by Calgary's youth, and for many, represents their first paying jobs.[86] As a non-profit organization, however, the Calgary Stampede relies on an army of volunteers.[87] Over 2,000 volunteers are needed to serve on one of over 50 committees responsible for planning and organization, ensuring it maintains its western values, governance and supporting the board of directors.[88] Nearly half of all volunteers have served for more than 10 years, and some as long as 60.[89]

Animal welfare

Animal welfare groups have voiced concern over the Calgary Stampede and rodeos in general, arguing that they are inhumane.[90] Stampede officials defend the sport, calling the animals the "stars of the show" and stating that they are "passionate about the proper treatment of animals".[91] The Calgary Humane Society has found itself at odds with other organizations by choosing to work with the Stampede to ensure that stress on the animals is kept to a minimum.[92] It is one of two such groups, in addition to veterinarians, who are on hand to monitor the rodeo.[91]

Though popular, chuckwagon racing is a particular source of controversy. Animal rights groups protest the event, arguing that the sport causes undue suffering on the horses.[93] Racers admit the sport is dangerous, and it is not uncommon for at least one horse to die during each Stampede. In 2002, for instance, six horses were killed as a result of crashes.[94] Racers defend their sport amidst the controversy, arguing that the animals are well cared for, and that allowing them to race saves many horses from prematurely going to slaughter.[95] The sport is also dangerous for riders. Four racers and a spectator have died as a result of crashes over the years.[96]

Tie down roping is also the focus of efforts to eliminate the event.[97] Rule changes in 2011 were set in place to enforce the rules of the Canadian Professional Rodeo Association and to provide penalties to competitors who improperly handle calves in the tie down roping event.[98]

In England, political pressure by the animal activist community was placed upon travel agencies to stop offering tourism packages to the Stampede, and in 2010 over 50 members of the British Parliament passed a motion asking their Canadian counterparts to ban rodeo.[99] Several groups petitioned the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge to cancel their planned attendance in 2011.[100][101] The couple chose to participate, attending and participating in a private demonstration of rodeo and chuckwagon events.[102]

The Stampede periodically modifies its rules in efforts to make events safer for both the animals and cowboys. Following a particularly deadly series of accidents in 1986 where nine horses died in chuckwagon racing incidents alone – including five horses in one spectacular crash – humane society officials, fans and even some drivers called for major changes to the races, while others called for the sport to be banned entirely.[103] Numerous rule changes were announced prior to the 1987 event, including a redesign of the wagons, new penalties, the potential of suspension for dangerous driving and medical and drug checks for riders and horses. The Calgary chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals accepted the changes, stating it would not call for the sport to be banned given Stampede officials had moved to improve animal safety.[104]

Such changes have not completely eliminated all risks; periodic accidents have continued to result in the deaths of humans, horses and livestock.[96] One of the deadliest incidents in Stampede history occurred in 2005 when, late in a trail ride meant to help celebrate the province's centennial, a group of about 200 horses spooked and in the melee nine horses were killed after they were pushed off a city bridge into the Bow River.[105] While similar trail rides had been completed without incident in the past,[105] Stampede officials announced they would not attempt any further rides unless they could ensure safety of the horses.[106]

Rule modifications have continued over the years, including further changes to chuckwagon racing announced in 2011 that limited the number of races in which each horse could compete and reducing the number of outriders from four to two in a bid to reduce congestion on the track.[107] Several changes were made to rodeo events as well, including disqualifications to cowboys when an animal injury occurs, or if they improperly catch or jerk down a calf in the tie down roping event.[98] The rule changes were announced after six animals died at the 2010 Stampede and have been met with mixed reactions from both cowboys and animal welfare groups.[108] However, during the chuckwagon race on opening night of the Calgary Stampede in July 2011, a horse was euthanized after slipping and breaking its leg on the track.[109]

Community

Pancake breakfasts

The pancake breakfast is a local institution during Stampede.[110] Dozens are held throughout the city each day hosted by community groups, corporations, churches, politicians and the Stampede itself.[110] The tradition of pancake breakfasts dates back to the 1923 Stampede when a chuckwagon driver by the name of Jack Morton invited passing citizens to join him for his morning meals.[111]

The largest is the breakfast hosted at the Chinook Centre shopping mall. Four hundred volunteers are required to feed over 60,000 people who attend the one-day event that had its 50th anniversary in 2010.[111] Other groups, such as the Calgary Stampede Caravan, feed as many as 120,000 people over the ten days of Stampede.[112] The rising popularity of the barbecue grill in the 1960s and immigrants from the city's population boom at the time brought with it the growth of community and company barbecues throughout the city during Stampede.[18] Community booster groups have exported the tradition across the country, notably the Calgary Grey Cup Committee, whose volunteers have traveled across the country to serve pancake breakfasts on the day of the Canadian Football League championship game for over three decades, sometimes in spite of poor weather conditions for the November game.[113]

Stampede parties

The size and number of parties each year during Stampede is viewed as an indicator of Calgary's economic strength.[114] Corporations and community groups hold lavish events throughout the city for their staff and clients,[114] while bars and pubs erect party tents, the largest of which will draw up to 20,000 people per day.[115] The owner of that tent and several other establishments, Paul Vickers, estimates that he makes up to 20% of his annual revenue during the ten days of Stampede alone.[116] Some parties have become known for heavy drinking and relaxed morals,[117] so much so that one hotel's satirical ad promising to safely store patron's wedding ring during Stampede was widely viewed as a legitimate offer.[118] Party goers often face consequences, as lawyers have noted a significant increase in divorce filings in the weeks following the Stampede, primarily on claims of infidelity,[119] clinics see an increase in people seeing testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases,[118] and Calgary is said to experience an annual baby boom each April – nine months after the event.[117]

Relationship with the city

The Stampede has become inexorably linked to the city's identity. Calgary has long been called the "Stampede city",[120] and carries the informal nickname of "Cowtown".[121] The event's iconic status offers Calgary global publicity and plays a significant role in defining the city's image.[122] Calgary's Canadian Football League team has been called the Stampeders since 1945, and it is a name shared by other teams in various sports throughout the city's history, including the Stampeders hockey team that operated in the years following World War II.[21]

The Calgary Stampede has strong polling support within the province. A 2006 Ipsos-Reid poll found that 86 percent of Albertans felt that it raised the civic quality of life and considered it one of the region's most important cultural events. Nearly three in four stated they look forward to the annual event.[123]

Part of the event's success can be attributed to the close relationship the Stampede has often shared with both the civic government and community leaders. The Stampede operates on city owned land, pays no property tax on its lease, and typically faces little to no political interference from City Hall.[124] Mayors of Calgary and city aldermen have sat on the Stampede Board of Governors at the same time they occupied public office and the Stampede's ability to convince the city's wealthy and influential citizens to volunteer their time has allowed the organization to gain a high profile within the city.[125]

Likewise, the Stampede has support from the media,[126] a position that resulted in national scrutiny in 2009 when both major local newspapers refused to run anti-rodeo ads sponsored by the Vancouver Humane Society.[92] While the Calgary Herald simply refused to run the ad, the Calgary Sun defended its position in an editorial. The Sun refuted charges it was kowtowing to the Stampede and justified its refusal by claiming "we are Calgarians and allowing a group of outsiders to come in and insult a proud Calgary tradition seemed just plain wrong."[127] The Herald reversed its decision a year later, running a full page ad sponsored by the Vancouver Humane Society.[128]

Economic impact and tourism

Civic leaders have consistently made note of the Stampede's impact on the city. Mayor Andrew Davison claimed in 1944 that the event "had done more to advertise Calgary than any single agency," an opinion that has been echoed by his successors.[129] Stampede officials have made similar claims, arguing that the event is one of Canada's most important tourist attractions.[130] The Canadian Tourism Commission placed the event in its Signature Experiences Collection, one of six such events or locations in Alberta.[131]

While 70 percent of attendees are from the Calgary region,[132] officials work to promote the event across the globe.[133] As such, the Calgary Stampede is famed around the world.[134][135] The Stampede draws foreign visitors primarily from the United States, Great Britain and Australia, and is experiencing growing attendance by tourists from Asia and South America.[136]

Stampede officials estimated in 2009 that the city of Calgary felt a gross economic impact of $172.4 million from the ten-day event alone, with a wider provincial total of $226.7 million.[137] In terms of economic impact, the Stampede is the highest grossing festival in Canada, ahead of Ottawa's Winterlude, the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, and the Just for Laughs festival in Montreal.[138] Additionally, Stampede officials estimate that for every dollar spent at Stampede Park, tourists spend $2.65 in the rest of the city.[137] A poll conducted in 2011 found that 40 percent of Calgarians who intended to attend the Stampede expected to spend $150–$400 over the course of the event, and 7 percent stated that the would spend more than that.[139]

See also

- Canadian Finals Rodeo, Canada's other big rodeo

- Raymond Stampede, Canada's oldest rodeo

- Festival Western de Saint-Tite, eastern Canada's largest rodeo

- Festivals in Alberta

- Reg Kesler

References

- Notes

- ^ "2010 a year of wins and losses for Stampede; attendance falls by 41,242", Calgary Herald, 2010-07-19, retrieved 2010-07-20

- ^ Yahoo! Stampede parade kicks off 'greatest outdoor show on earth', Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2008-07-04, retrieved 2011-07-09

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dudley, Wendy (1997-07-03), "Guy's Stampede dream", Calgary Herald, p. SS2

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 26

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 27

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 29

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 30

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 5

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 32

- ^ a b c Dixon & Read 2005, p. 36

- ^ 2009 Calgary Stampede Evening Show Program, Calgary Stampede Board, p. 8

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 38

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 10

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 42

- ^ A royal Calgary Stampede, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ a b c Dixon & Read 2005, p. 43

- ^ a b Gray 1985, p. 136

- ^ a b Gray 1985, p. 137

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 144

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 12

- ^ a b Gray 1985, p. 142

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 140

- ^ a b c Gray 1985, p. 143

- ^ a b c d Dixon & Read 2005, p. 44

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 45

- ^ Calgary Stampede attendance falls slightly, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2009-07-13, retrieved 2010-05-19

- ^ a b c "Stampede Park", Calgary Sun, pp. 2–3, 2011-07-08

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 152

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 158

- ^ "'We've erased Victoria Park'", Calgary Herald, 2007-05-15, retrieved 2011-01-09

- ^ Toneguzzi, Mario (2010-11-09), "Calgary Stampede Park moves ahead with $400-million expansion", Calgary Herald

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 115

- ^ a b c 2009 Stampede parade, CTV Calgary, 2009-07-03, retrieved 2010-05-28

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 14

- ^ "Hot, sunny parade kicks off Calgary Stampede", Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2010-07-09, retrieved 2011-07-08

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 74

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 11

- ^ Schneider, Katie (2011-07-09). "Tourism officials tally royal boost". Calgary Sun. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 78

- ^ Baker, Linda (2009-01-20), "A boom in office towers in Calgary", New York Times, retrieved 2010-05-16

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 205

- ^ $1 million Sunday lives up to its billing at Stampede, CanWest Media, 2008-07-14, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ Rodeo, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ 2009 Calgary Stampede Media Guide (PDF), Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, p. 75

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 67

- ^ Stampede Ranch, Calgary Stampede Board, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 69

- ^ CBC and the Calgary Stampede announce five-year broadcast agreement (PDF), 2010-07-16

- ^ History, Western Professional Chuckwagon Association, retrieved 2011-01-09

- ^ a b Primrose, Tom, Calgary Herald Magazine, p. 1

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Chuckwagon races – History, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ "Calgary's half-mile of hell", The Globe and Mail, Toronto, 2009-07-08, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 64

- ^ Chuckwagon races, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ CBC and the Calgary Stampede announce five-year broadcast agreement (PDF) (PDF), Calgary Stampede, 2010-07-16, retrieved 2011-01-09

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 247

- ^ Down, John (2010-03-05), "Stampede tarp auction rebounds with $2M take", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ Lewis, Nick (2009-03-19), "Tarp auction tells tale of Calgary's economy", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2010-05-21

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 106

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 107

- ^ Cutting Horse Competition, Calgary Stampede Board, retrieved 2011-06-07

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 110

- ^ Agrium Ag-tivity in the City, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 112

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 332

- ^ Foran 2008, pp. 118–119

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 113

- ^ Foran 2008, pp. 112–113

- ^ Highlights for Thursday, July 2, 2009, Calgary Stampede, 2009-07-03, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ Coca-Cola stage, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ Nashville North, Calgary Stampede, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ a b Penty, Rebecca (2011-07-11), "Vendors hope to cash in on Stampede visitors", Calgary Herald, p. B1

- ^ Foran 2008, pp. 48–52

- ^ a b Foran 2008, pp. 54–55

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 80

- ^ About Indian Village, Calgary Stampede Board, retrieved 2011-06-18

- ^ Stampede Queen and Princesses chosen, CTV Calgary, 2010-10-03, retrieved 2011-06-18

- ^ a b Dixon & Read 2005, p. 116

- ^ "More top talent signed for big grandstand show", Calgary Herald, p. 45, 1966-05-10, retrieved 2011-04-17

- ^ "Young Canadians taking tunes to many exhibitions", Calgary Herald, p. 16A, 1973-07-03, retrieved 2011-04-17

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 117

- ^ a b c d Dixon & Read 2005, p. 119

- ^ Janofsky, Michael (1988-02-14), "An emotional opening in Calgary; Games begin on high note", New York Times, retrieved 2011-04-17

- ^ Calgary Stampede Showband, Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, retrieved 2011-04-17

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 127

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 128

- ^ Gray 1985, p. 184

- ^ 2009 Annual Report to the Community, Calgary Stampede Board, p. 11

- ^ Dixon & Read 2005, p. 123

- ^ Gerson, Jen (2010-07-04), "Lonely but steadfast anti-rodeo activists say support growing", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2011-04-18

- ^ a b Tetley, Deborah (2007-05-24), "Rodeo ban renews Stampede criticism", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2011-04-18

- ^ a b Anti-rodeo ad divides humane societies, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2009-06-29, retrieved 2011-04-16

- ^ Fong, Petti (2010-07-19), "Stampede shuts down but animal rights debate lingers", Toronto Star, retrieved 2011-01-09

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 245

- ^ Spencer, Donna (2010-07-19), "Horse deaths have many questioning Stampede chuckwagon races", Toronto Star, retrieved 2011-01-09

- ^ a b Deadly accidents at the Calgary Stampede, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2005-07-04, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ Calf roping at the Calgary Stampede: Should it be banned?, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2010-07-08, retrieved 2011-04-18

- ^ a b New chuckwagon and rodeo rules make safety a priority for Stampede, Global News Calgary, 2011-02-24, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ Calgary rodeo condemned by U.K. MPs, activists, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2010-07-08, retrieved 2011-04-18

- ^ "Prince William and Kate Middleton urged to avoid 'cruel' rodeo on Canada visit by animal rights group", Daily Mirror, 2011-06-10, retrieved 2011-06-25

- ^ "PETA urges William and Kate to skip planned visit to Stampede", Globe and Mail, 2011-06-30, retrieved 2011-07-02

- ^ McMurray, Jenna (2011-07-08). "Stampede welcomes royalty as Will and Kate don their duds". Calgary Sun. p. 3.

- ^ Cunningham, Jim (1986-07-15), "Tragic chuckwagon races bring call for tougher rules", Calgary Herald, pp. A1–A2, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ "Rules toughened at chuckwagon races", Montreal Gazette, p. B6, 1986-11-06, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ a b 9 horses die during Calgary Stampede drive, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2005-07-04, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ D'Aliesio, Renata (2005-12-17), "Stampede will not rule out city rides", Calgary Herald, p. B1

- ^ Fisher, Scott (2011-02-15), "Stampede tightens race rules", Calgary Sun, p. 10

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Storry, Lea (2011-02-24), "Safety rules beefed up for Calgary Stampede events", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ "Chuckwagon horse euthanized on the first night of Stampede". ctv.ca. 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ a b Brooker, Kevin (2011-07), "Man vs. Pancake: How the breakfast was won... right here", Swerve Magazine, Postmedia Network, pp. 37–41

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Fortney, Valerie (2010-07-08), "Chinook Centre hosts 50 years of breakfast fun", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2010-07-10

- ^ Dormer, Dave (2010-07-09), "120,000 expected at Stampede breakfasts", Calgary Sun

- ^ Bielski, Zosia (2007-11-23), "The breakfast must go on", National Post, retrieved 2011-07-11

- ^ a b Toneguzzi, Mario (2011-07-08). "Economy spurs higher interest in Stampede corporate parties". Calgary Herald. p. B3.

- ^ "Party tents popping up". CTV News. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Date=ignored (|date=suggested) (help) - ^ Pitts, Gordon (2011-07-06). "Energized by oil's resurgence, Calgary gets ready to cash in". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ a b Rutherford, Kristina (2010-07-18). "Buckle bunnies, whiskey and Stampede rumours". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ a b Graveland, Bill; Montgomery, Shannon (2008-07-11). "CALGARY STAMPEDE: Debauchery... divorce, disease". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ "Divorce rate rises after Calgary Stampede". United Press International. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Date=ignored (|date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Calgary now is recognized as 'Stampede city'", Calgary Herald, p. 19, 1953-07-04, retrieved 2011-04-16

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 166

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 148

- ^ Calgary Stampede Still The Greatest Outdoor Show On Earth For Albertans, Ipsos-Reid, 2006-06-23, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 150

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 151

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 153

- ^ Norrie, Gordon (2009-06-30), "No sacred cows in our line of work", Calgary Sun, retrieved 2011-04-16

- ^ Anti-rodeo ad runs in Calgary paper, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2010-07-05, retrieved 2011-04-16

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 152

- ^ Foran 2008, p. 328

- ^ Guttormson, Kim (2011-07-12). "Calgary Stampede branded in tourism series". Calgary Herald. p. D1. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ Guttormson, Kim (2011-05-12), "Fuel price hikes hurt prospects for Calgary tourism rebound", Edmonton Journal, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Barcoe, Chris (2011-05-26), "Calgary looks for niche to tempt tourists from China", Calgary Herald, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Hough, Andrew; Rayner, Gordon (2011-05-30), "Royal tour: Duke and Duchess of Cambridge's 14,000-mile first official trip", The Telegraph, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Campbell, Al (2011-05-22), Canadian rodeo a rural experience for urban dwellers, Xinhua News Agency, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Gandia, Renato (2011-07-11). "Stampede gets foreign tourism boost". Calgary Sun. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ a b "Stampede an event of numbers", Calgary Herald, 2009-07-04, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Backland, Jason (2010-07-04), Biggest festivals in Canada, MSN Canada, retrieved 2011-06-04

- ^ Toneguzzi, Mario (2011-07-08), "Calgarians big Stampede spenders", Calgary Herald, p. D3

- General

- Dixon, Joan; Read, Tracey (2005), Celebrating the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, Canmore, Alberta: Altitude Publishing Canada Ltd., ISBN 1-55153-939-X

- Foran, Max, ed. (2008), Icon, Brand, Myth:The Calgary Stampede (PDF), Athabasca, Alberta: Athabasca University Press, ISBN 978-1-897425-05-3

- Gray, James H. (1985), A Brand of its Own: The 100 year history of the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Western Produce Prairie Books, ISBN 0-88833-163-0