Arab–Khazar wars: Difference between revisions

Miniapolis (talk | contribs) →Strategic background and motives: Tweaked header |

Busulb Vash (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

*[[Ras Tarkhan]] |

*[[Ras Tarkhan]] |

||

*[[Bulchan]]}} |

*[[Bulchan]]}} |

||

[[Aguk Shagin]] {{POW}} |

|||

|strength1= |

|strength1= |

||

|strength2= |

|strength2= |

||

Revision as of 15:00, 24 April 2023

| Arab–Khazar wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquests | |||||||

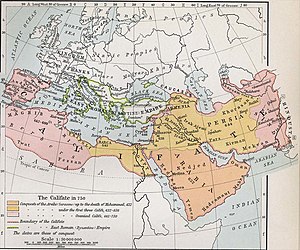

Map of the Caucasus region c. 740, following the end of the Second Arab–Khazar War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Rashidun Caliphate (until 661) Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) Abbasid Caliphate (after 750) | Khazar Khaganate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Aguk Shagin (POW) | |||||||

The Arab–Khazar wars were a series of conflicts fought between the armies of the Khazar Khaganate and the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid caliphates and their respective vassals. Historians usually distinguish two major periods of conflict, the First Arab–Khazar War (c. 642–652) and Second Arab–Khazar War (c. 722–737);[2][3] the wars also involved sporadic raids and isolated clashes from the mid-seventh century to the end of the eighth century.

The wars were a result of attempts by the nascent caliphate to secure control of the South Caucasus (Transcaucasia) and North Caucasus, where the Khazars were already established. The first Arab invasion began in 642 with the capture of Derbent and continued with a series of minor raids, ending with the defeat of a large Arab force led by Abd al-Rahman ibn Rabiah outside the Khazar town of Balanjar in 652. Large-scale hostilities then ceased, apart from raids by the Khazars and the North Caucasian Huns on the autonomous Transcaucasian principalities during the 660s and 680s. The conflict between the Khazars and the Arabs (now under the Umayyad Caliphate) resumed after 707 with occasional raids back and forth across the Caucasus Mountains, intensifying after 721 into a full-scale war. Led by distinguished generals al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah and Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik, the Arabs recaptured Derbent and the southern Khazar capital of Balanjar; these successes had little impact on the nomadic Khazars, however, who continued to launch devastating raids deep into Transcaucasia. In a major 730 invasion, the Khazars decisively defeated Umayyad forces at the Battle of Ardabil (killing al-Jarrah); in turn, they were defeated the following year and pushed back north. Maslama then recovered Derbent, which became a major Arab military outpost and colony, before he was replaced by Marwan ibn Muhammad (the future caliph Marwan II) in 732. A period of relatively-localized warfare followed until 737, when Marwan led a massive expedition north to the Khazar capital Atil on the Volga. After securing submission by the khagan, the Arabs withdrew.

The 737 campaign marked the end of large-scale warfare between the two powers, establishing Derbent as the northernmost Muslim outpost and securing Muslim dominance of Transcaucasia. At the same time, continuing warfare weakened the Umayyad army and contributed to the fall of the dynasty in the 750 Abbasid Revolution. Relations between the Muslims of the Caucasus and the Khazars remained largely peaceful thereafter, apart from two Khazar raids in the 760s and in 799 resulting from failed efforts to secure an alliance through marriage between the Arab governors (or local princes) of the Caucasus and the Khazar khagan. Occasional warfare continued in the region between the Khazars and the Muslim principalities of the Caucasus until the collapse of the Khazar state in the late 10th century, but the great eighth-century wars were never repeated.

Background and motives

The Caucasus as a frontier between the steppe and the settled world

The Arab–Khazar wars were part of a long series of military conflicts between the nomadic peoples of the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the more settled regions south of the Caucasus range. The two primary routes over the mountains, the Darial Pass ("Alan Gates") in the centre and the Pass of Derbent ("Caspian Gates") in the east along the Caspian Sea, have been used as invasion routes since Classical Antiquity.[1][4] Consequently, the defence of the Caucasus frontier against the destructive raids of the steppe peoples such as the Scythians and the Huns came to be regarded as one of the chief duties of imperial regimes of the Near East.[4] This is reflected in the popular belief among Middle Eastern cultures that Alexander the Great had with divine assistance barred the Caucasus against the hordes of "Gog and Magog". According to historian Gerald Mako, the latter were a stereotypical archetype of "northern barbarians", as conceived by the settled civilizations of Eurasia: "uncivilized savages who drank blood, who ate children, and whose greed and bestiality knew no limits"; should Alexander's barrier fail and Gog and Magog break through, the Apocalypse would follow.[5]

Starting with Peroz I (r. 457–484), the shahs of the Sasanian Empire built a line of stone fortifications to protect the vulnerable frontier along the Caspian shore; when completed under Khosrow I (r. 531–579), this stretched over 45 kilometres (28 mi) from the eastern foothills of the Caucasus to the Caspian Sea. The fortress of Derbent was the strategically crucial centre-point of this fortification complex, as evoked by its Persian name Dar-band, lit. 'Knot of the Gates'.[6][7] The Turkic Khazars appeared in the area of modern Dagestan in the latter half of the 6th century, initially as subjects of the First Turkic Khaganate, but following the latter's collapse, they emerged as an independent and dominant power in the area of the northern Caucasus by the 7th century.[7] As the most recent steppe power in the region, early medieval writers came to identify the Khazars with Gog and Magog,[8] and the Sassanid fortifications at Derbent as Alexander's wall.[7]

The Khazars themselves first campaigned in Transcaucasia during the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628, as subjects of the Western Turkic Khaganate. The Turks sacked Derbent and joined the Byzantines in their siege of Tiflis. Their contribution proved decisive for the eventual Byzantine victory in the war. For a few years afterwards, as Sasanian power collapsed, the Khazars or the Western Turks exercised some control over Caucasian Iberia (approximately modern Georgia), Caucasian Albania (modern Republic of Azerbaijan) and Adharbayjan (modern Iranian Azerbaijan), while the western half of Transcaucasia, i.e., Armenia, was in Byzantine hands. However, after the death of the Khazar or Western Turkic ruler in an internal conflict c. 630/632, the Khazar activity in eastern Transcaucasia ceased.[9][10] However, around 630, the Western Turkic khagan, Tong Yabghu, was assassinated by a rival faction, and the project of extending Turkic/Khazar control into Transcaucasia was abandoned. The area returned to Sasanian influence by 632.[11]

Opposing armies

The eastern Caucasus range became the main theatre of the Arab–Khazar conflict, with the Arab armies aiming to gain control of Derbent (in Arabic, Bab al-Abwab, 'Gate of Gates') and the Khazar cities of Balanjar and Samandar. Their locations have yet to be established with certainty by modern researchers,[a] but both cities are referred to as Khazar capitals by different Arab writers, and may have functioned as winter and summer capitals respectively. It was only later, under the impact of the Arab attacks, that the Khazars moved their capital further north, to Atil (Arabic al-Bayda) on the mouths of the Volga.[12][13]

Arabs

Like other Near Eastern peoples, the Arabs were already familiar with the legend of Gog and Magog, who appear even in the Quran (Yaʾjuj wa-Maʾjuj). Following the early Muslim conquests, these perceptions were enhanced by incorporating many of the cultural conceptions of their new subjects.[14] The nascent Muslim Caliphate regarded itself as heir to the Sassanid, and to a lesser extent, Byzantine, tradition and worldview. As a result, the Arab caliphs also adopted the notion that, in the words of Mako, it was their duty "to protect the settled, i.e. the civilized world from the northern barbarian". This imperative was further reinforced by the Muslim division of the world into the 'House of Islam' or Dar al-Islam and the 'House of War' (Dar al-Harb), to which the pagan Turkic steppe peoples like the Khazars were consigned.[15][b]

On the other hand, while their Byzantine and Sassanid predecessors simply sought to contain the steppe peoples through fortifications and political alliances, the Arabs were "expansionists interested in conquest", according to the historian David Wasserstein, and actively pursued a northward expansion, posing a direct threat to the very survival of the Khazars as an independent polity.[16] Likewise, the historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship emphasizes that "the early Muslim caliphate was an ideological state" dedicated to the doctrine of jihad, "the struggle to establish God's rule in the earth through a continuous military effort against the non-Muslims".[17] As a result, the early Muslim state was highly geared towards expansion, with all able-bodied adult male Muslims being liable to be called up,[18] and providing an enormous manpower pool—the historian Hugh N. Kennedy estimates 250,000–300,000 men inscribed as soldiers (muqatila) in the various provincial army registers in c. 700.[19]

Arab armies of the early Muslim conquests contained sizeable contingents of both light and heavy cavalry,[20] but relied primarily on their infantry, to the extent that the Arab cavalry was often limited to skirmishing during the initial phases of a battle, before dismounting and fighting on foot.[21] Against cavalry charges, the Arab armies dug trenches and formed up kneeling in a spear wall behind them.[22] This tactic attests to the great discipline of the Arab armies, and especially the elite Syrian troops, which were almost a professional, standing army. According to Kennedy, it was their high degree of training and discipline that "gave them the advantage over their enthusiastic but disorganised enemies".[23]

Khazars

The Khazars followed a strategy common to their nomadic predecessors: their raids might reach deep into Transcaucasia, and even into Mesopotamia and Anatolia, but they were, according to historian Peter B. Golden, not aimed at conquest. Rather, Golden writes, they were "typical of nomads testing the defenses of their sedentary neighbors", as well as a means of gathering booty, the acquisition and distribution of which was fundamental to the maintenance of tribal coalitions. According to Golden, for the Khazars, the strategic stake of the conflict was chiefly control of the passes of the Caucasus.[24] At the same time, Albania at least was likely regarded by the Khazars as rightfully theirs, a legacy of the last Byzantine–Sassanid war.[25] According to the historian Bori Zhivkov, "it is no surprise that they fought fiercely with the Arabs precisely for these lands up to the 730s".[25]

The sources do not provide enough details about the composition or tactics of Khazar armies, and even the names of the Khazar commanders are rarely recorded.[26] While the Khazars had adopted elements of the civilizations of the south and possessed towns, they remained a largely tribal and semi-nomadic power. Like other steppe societies originating in Central Asia, they practiced a very mobile form of warfare, relying on highly skilled and hardy cavalry.[27] The rapid movements, and the ability for sudden attacks and counterattacks of the Khazar cavalry, are emphasized in the sources,[28] and in the few detailed descriptions of pitched battles, the Khazar cavalry plays a major role, launching the opening attacks of the engagement.[29] The presence of heavy ('cataphract') cavalry is not recorded, but archaeological evidence attests to the use of heavy armour for the riders, and possibly for the horses as well.[30] Likewise, the presence of Khazar infantry must be assumed, especially during siege operations, although it is never explicitly mentioned.[30] Modern historians point especially to the use of advanced siege machines to show the high level of military sophistication the Khazars possessed, equal to that of any other contemporary army.[31][32] On the other hand, the less rigidly organized, semi-nomadic nature of the Khazar state also worked to their advantage against the Arabs, as they lacked a permanent administrative centre, whose loss would paralyze the government and force them to surrender.[27]

The Khazar army was composed not only of Khazar troops, but also of vassal princes and allies. Its overall size is unclear; references to 300,000 men in the invasion of 730 are clearly exaggerated.[33] The historian Igor Semyonov observes that the Khazars "never entered into battle without having a numerical advantage" over their Arab opponents, which forced the latter to often withdraw. This attests, according to Semyonov, to the Khazars' skill in logistics and their ability to gather accurate information about their opponents' movements, as well as the layout of the country, the condition of roads, etc.[34]

Connection with the Arab–Byzantine conflict

To an extent, the Arab–Khazar wars were also linked to the long-lasting struggle of the Caliphate against the Byzantine Empire along the eastern fringes of Anatolia, a theatre of war which adjoined the Caucasus. The Byzantine emperors pursued close relations with the Khazars, which amounted to a virtual alliance for most of the period in question, including such exceptional acts as the marriage of emperor Justinian II (r. 685–695, 705–711) to a Khazar princess in 705.[35][36] The possibility of the Khazars linking up with the Byzantines through Armenia was a grave threat to the Caliphate, especially given its proximity to the Umayyad Caliphate's metropolitan province of Syria.[1] This did not materialize, and Armenia was left largely quiet, with the Umayyads granting it wide-ranging autonomy and the Byzantines likewise refraining from active campaigning there.[37] Indeed, given the common threat posed by the Khazar raids, the Umayyads found the Armenians (and the neighbouring Georgians) willing allies against the Khazars.[38]

Some Byzantinists, notably Dimitri Obolensky, suggested that the Arab expansion against the Khazars was motivated by a desire to outflank the Byzantine defences from the north, and envelop the Byzantine Empire in a pincer movement. However, this idea is rejected as far-fetched by modern scholars. As Wasserstein comments, it is a scheme of extraordinary ambition, which "requires us to accept that Byzantium had succeeded already at this primary stage in persuading the Muslims that it could not be conquered", and furthermore that the Muslims possessed "a far greater knowledge and understanding of the geography of Europe" than can be demonstrated for the time in question. Mako likewise remarks that such a grand strategic plan is not borne out by the rather limited nature of the Arab–Khazar conflict until the 720s.[39][40] It is more likely that the northward expansion of the Arabs beyond the Caucasus was, at least initially, the result of the onward momentum of the early Muslim conquests, with the local Arab commanders seeking to exploit opportunities, haphazardly and without any overall planning. The expansion may even have been in direct contravention to caliphal orders, repeating a frequent pattern during this period.[41] From a strategic perspective, it is far more probable that it was the Byzantines who encouraged the Khazars to attack the Caliphate to relieve the mounting pressure on their own eastern frontier in the early 8th century.[38] Byzantium profited considerably from the diversion of the Muslim armies northwards in the 720s and 730s, resulting in another marriage alliance, between the future emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775) and the Khazar princess Tzitzak in 733.[42][43][c]

Gaining control over the northern branch of the Silk Road by the Caliphate has been suggested as a further motive for the conflict, but Mako disputes this claim by pointing out that warfare declined at precisely the period of the greatest expansion of traffic along the Silk Road, i.e. after the middle of the 8th century.[46]

First Arab–Khazar War and aftermath

First Arab invasions

Muslim state at the death of Muhammad Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate

The Khazars and the Arabs came into conflict as a result of the first phase of Muslim expansion: by 640, following their conquest of Byzantine Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, the Arabs had reached Armenia.[47][48] The Arabic and Armenian sources differ considerably on the details and chronology of the subsequent Arab conquest of Armenia, but it appears that in 652, the Armenian princes offered their submission to the Arabs, and by 655, both the Byzantine and Persian halves of Armenia had been subjugated.[48][49] Arab rule was overthrown during the First Muslim Civil War (656–661), but after its end, the Armenian princes quickly returned to their tributary status towards the newly established Umayyad Caliphate.[50] The Principality of Iberia concluded a similar treaty with the Arabs, while only Lazica, on the Black Sea coast, remained under Byzantine influence.[48] Neighbouring Adharbayjan was conquered in 639–643,[51] and raids were launched into Arran (Caucasian Albania) under Salman ibn Rabiah and Habib ibn Maslama in the early 640s, leading to the submission of the local cities. As in Armenia, firm Arab rule was not established there until after the end of the First Muslim Civil War.[52]

According to the Arab chroniclers, the first attack on Derbent was launched in 642 under Suraqah ibn Amr, with Abd al-Rahman ibn Rabiah in command of his vanguard. According to the History of the Prophets and Kings of al-Tabari, the Persian governor of Derbent, Shahrbaraz, offered to surrender the fortress to the Arabs and even to aid them against the unruly native Caucasian peoples, if he and his followers were relieved of the obligation to pay the jizya tax. The proposal was accepted and ratified by Caliph Umar (r. 634–644).[53][54] Al-Tabari reports that the first Arab advance into Khazar lands occurred after the capture of Derbent, claiming that Abd al-Rahman ibn Rabiah reached Balanjar, without suffering any losses, and that his cavalry raided up to 200 parasangs—about 800 kilometres (500 mi)—to the north of it as far as al-Bayda on the Volga, which in later times was the Khazar capital. Both this dating and the improbable claim that the Arabs suffered no casualties have been disputed by modern scholars.[12][55] Based at Derbent, Abd al-Rahman launched frequent raids against the Khazars and local tribes over the following years, but these were small-scale affairs, and no event of major note is recorded in the sources.[56][57]

In 652, disregarding the instructions of the Caliph urging caution and restraint, Abd al-Rahman—or, according to Baladhuri and Ya'qubi, his brother Salman[57]—led a strong army north, aiming to take Balanjar. The town was besieged for a few days, with both sides using catapults, until the arrival of a Khazar relief force, coupled with a general sortie of the besieged forces, ended in a heavy defeat for the Arabs. Abd al-Rahman and 4,000 Muslim troops were left dead on the field, while the rest fled to Derbent, or as far away as Gilan, in northern modern Iran.[58][59]

Khazar and Hunnic raids into Transcaucasia

Due to the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War and the priorities on other fronts, the Arabs refrained from repeating an attack on the Khazars until the early 8th century.[60][61] Furthermore, despite the re-establishment of Arab suzerainty after the end of the civil war, the various tributary Transcaucasian principalities were not yet firmly under Arab rule, and their resistance, encouraged by Byzantium, could not be overcome at the time. For several decades after the initial Arab conquest, considerable autonomy was left to the local rulers, with Arab governors obliged to work with them and with little forces of their own.[62] The Khazars, on their part, refrained from large-scale interventions in the south; thus, the pleas for assistance by the last Sasanian shah, Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651), were not answered.[63] Indeed, in the aftermath of the Arab attacks, the Khazars abandoned Balanjar and moved their capital further north, in an attempt to evade the reach of the Arab armies.[64] On the other hand, Khazar auxiliaries, along with Abkhazian and Alan troops, are recorded as fighting alongside the Byzantines in 655.[63]

The only recorded hostilities for the second half of the century consist of a few raids into the Transcaucasian principalities that were loosely under Muslim dominion, mostly in search of plunder. In a raid into Albania in 661/2, they were defeated by the local prince, but in 683 or 685 (also a time of civil war in the Muslim world), a large-scale raid across Transcaucasia was more successful, capturing much booty and many prisoners. The presiding princes of Iberia (Adarnase II) and Armenia (Grigor I Mamikonian) were killed trying to oppose that raid.[3][65] At the same time, the North Caucasian Huns also launched attacks on Albania in 664 and 680. In the first case, Prince Juansher was obliged to marry the daughter of the Hunnic king. Modern scholars debate whether the Huns acted independently or as Khazar proxies, but several historians consider that the Hunnic ruler, Alp Iluetuer, was a Khazar vassal. If so, then Albania was under some form of—albeit indirect—Khazar overlordship in the 680s.[66] The Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680) tried to counter Khazar influence by inviting Juansher to Damascus twice, and it is possibly as a reaction to these moves that the Khazar raid of 683/685 was launched.[67] Nevertheless, according to Thomas S. Noonan, this still evidences the "cautious nature of Khazar policy in the Southern Caucasus", as they shied from direct confrontation with the Umayyads, and only intervened to bolster their position in times of civil war.[68] Noonan opines that this caution was because the Khazars were at the time preoccupied with consolidating their own rule over the Pontic–Caspian steppe, and were satisfied with the "limited goal of bringing Albania into the Khazar sphere of influence".[68]

Second Arab–Khazar War

Relations between the two powers remained relatively quiet until the early years of the 8th century, by which time the stage for a new round of conflict was set: Byzantine political authority had been marginalized in the Caucasus, and the Caliphate tightened its grip on Armenia after the suppression of a large-scale rebellion in 705, placing it under direct Arab rule as the province of Arminiya. The Arabs and the Khazars now directly confronted each other for control of the Caucasus. Only the western parts of Transcaucasia, comprising modern Georgia, remained free from direct control by either of the two rival powers.[69]

Conflicting notices place the resumption of the conflict as early as 707, with a campaign by the Umayyad general Maslama, a son of Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705), in Adharbayjan and up to Derbent, which appears to have been under Khazar control at the time. Further attacks on Derbent are reported by different sources for 708 under Muhammad ibn Marwan and in the next year again by Maslama, but the most likely correct date for the recovery of Derbent is Maslama's expedition in 713/714.[12][70][71] The 8th-century Armenian historian Łewond reports that Derbent was in the hands of the Huns at that time, while the 16th-century chronicle Derbent-nameh claims that it was defended by 3,000 Khazars, and Maslama captured it only after an inhabitant showed him a secret underground passage. Łewond also claims that the Arabs, realizing that they could not hold the fortress, razed its walls.[72] Maslama then drove deeper into Khazar territory, trying to subdue the North Caucasian Huns (who were Khazar vassals).[12][71] The khagan of the Khazars confronted the Arabs at the city of Tarku, but the two armies did not engage for several days, apart from single combats by their champions. The imminent arrival of Khazar reinforcements under the general Alp', forced Maslama to quickly abandon his campaign and retreat to Iberia, leaving his camp with all its equipment behind as a ruse.[73] At about the same time, 80,000 Khazars are reported to have raided Albania.[71]

In 717, the Khazars raided in force into Adharbayjan. With the bulk of the Umayyad army besieging the Byzantine capital of Constantinople at the time, Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720) reportedly could only spare 4,000 men to confront the 20,000 invaders. Nevertheless, the Arabs under Hatim ibn al-Nu'man defeated and drove back the Khazars. Hatim returned to the Caliph with fifty Khazar prisoners, the first such event recorded in the sources.[74][75]

Escalation of the conflict

In 721/722, the main phase of the war began. In the winter of this year, 30,000 Khazars invaded Armenia and inflicted a crushing defeat on the mostly Syrian army of the local governor,[d] Ma'laq ibn Saffar al-Bahrani, at Marj al-Hijara ('Rocky Meadow') in February/March 722.[78][79][80] In response, Caliph Yazid II (r. 720–724) sent one of his most celebrated generals, al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah, with 25,000 Syrian troops north.[81] On the news of his approach, the Khazars retreated to the vicinity of Derbent, whose Muslim garrison was still holding out. Learning that the local Lezgin chief was in contact with the Khazars, al-Jarrah set up camp at the river Rubas and announced that the army would stay there for several days. Instead, in a night march he was able to enter Derbent without facing resistance.[82][83] From there, he launched raiding columns into Khazar territory ahead of the bulk of his own army. After joining up with the columns, al-Jarrah's army met a Khazar army at the river al-Ran, one day's march north of Derbent. According to the Derbent-nameh, al-Jarrah had 10,000 men, out of which 4,000 from vasal princes, while al-Tabari gives the Arab strength as 25,000. The Khazars, commanded by Barjik, one of the Khazar khagan's sons, are said to have numbered 40,000 men. In the ensuing battle, the Arabs were victorious, losing 4,000 men and the Khazars 7,000. Advancing north, the Arab army captured the settlements of Khamzin and Targhu, whose inhabitants were resettled elsewhere.[84][85]

Finally, the Arab army reached Balanjar. The city had featured strong fortifications during the first Muslim attacks in the mid-7th century, but apparently they had been neglected in the meantime, for the Khazars chose to defend their capital by ringing the citadel with a laager of 300 wagons tied together with ropes, a common tactic among nomads. The Arabs broke it apart and stormed the city on 21 August 722. Most of Balanjar's inhabitants were killed or enslaved, but a few, including its governor, managed to flee north.[86][87][32] The booty seized by the Arabs was so enormous that each of the 30,000 horsemen—probably an exaggeration by later historians—in the Arab army is said to have received 300 gold dinars from it.[88][89] Al-Jarrah is reported to have ransomed the wife and children of Balanjar's governor from captivity, for which the latter began sending information about the Khazars' movements to the Arab general. The Muslim sources also claim that the governor accepted an offer to recover all his belongings, as well as possession of Balanjar, on the condition of submitting to Muslim rule, but this is likely an invention.[88][90] At the same time, so many Khazar prisoners were made that al-Jarrah ordered some of them drowned in the Balanjar River.[88][89]

Al-Jarrah's army reduced the neighbouring fortresses as well, and continued their march north. The strongly garrisoned fortress city of Wabandar, counting 40,000 households according to the 13th-century historian Ibn al-Athir, capitulated in exchange for tribute. Al-Jarrah intended to advance to the next important Khazar settlement, Samandar, but had to cut his campaign short when he learned that the Khazars were gathering large forces there.[71][91][92] Despite their success, the Arabs had not yet defeated the main Khazar army, which like all nomad forces was not dependent on cities for supplies. The presence of this force near Samandar, as well as reports of rebellions among the mountain tribes in his rear, forced the Arabs to retreat to Warthan south of the Caucasus.[81][93][94] On his return, al-Jarrah reported on his campaign to the Caliph, requesting additional troops to defeat the Khazars,[93][94] an indication of both the severity of the fighting and an indication, according to Blankinship, that his campaign was not such a resounding success as portrayed in the Muslim sources.[81]

In 723, al-Jarrah is recorded to have led another campaign into Alania via the Darial Pass. The sources claim that he marched "beyond Balanjar", where he conquered several fortresses and captured much loot, but offer few details. However, modern scholars consider this to likely be an echo, or possibly the actual date, of the Balanjar campaign of 722.[81][93][94] In response, the Khazars raided south of the Caucasus, but in February 724, al-Jarrah inflicted a crushing defeat on them in a battle between the rivers Cyrus and Araxes that lasted for several days.[81] The new caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 724–743), promised to send reinforcements, but eventually failed to do so. Nevertheless, in 724 al-Jarrah captured Tiflis and brought Caucasian Iberia and the lands of the Alans under Muslim suzerainty.[94][95][96] These campaigns made al-Jarrah the first Muslim commander to campaign through the Darial Pass, secured the Muslims' own flank against a possible Khazar attack through the pass, and gave them a second invasion route into Khazar territory.[96]

In 725, the Caliph replaced al-Jarrah with his own brother Maslama, who already held the post of governor of the Jazira.[71][94][97] The appointment of Maslama testifies to the importance placed by the Caliph on the Khazar front, for he was one of the most distinguished generals of the Umayyad empire and a man of legendary status.[94][98] For the time being, Maslama remained in the Jazira and was more concerned with operations against the Byzantines. In his stead, he sent al-Harith ibn Amr al-Ta'i to the Caucasus front. In 725, al-Harith was engaged in consolidating Muslim authority in Caucasian Albania, campaigning along the Cyrus against the regions of al-Lakz and Khasmadan. He was probably also preoccupied with supervising that year's census.[94][98][99] The next year, Barjik launched a major invasion of Albania and Adharbayjan. The Khazars even laid siege to Warthan, during which they employed mangonels.[98][31][100] Al-Harith was able to defeat them on the banks of the Araxes and drive them back north of the river, but the Arabs' position was clearly precarious.[98][31][100]

This event prompted Maslama to take over personally the direction of the Khazar front in 727, where now he was faced, for the first time, by the khagan himself, as both sides escalated the conflict.[31] Maslama, probably reinforced with more Syrian and Jaziran troops, took the offensive. He recovered the Darial Pass, apparently lost in the period since al-Jarrah's expedition in 724, and pushed on into Khazar territory, campaigning there until the onset of winter forced him to return to Adharbayjan.[101][31] Whatever Maslama's achievements in this expedition, they were not enough. The next year, when he repeated his invasion, it ended in what Blankinship calls a "near disaster". Arab sources report that the Umayyad troops fought for thirty or even forty days in the mud, under continuous rainfall, before scoring a victory against the khagan on 17 September 728. How great that victory was, however, is open to question, because on his return Maslama was ambushed by the Khazars, whereupon the Arabs simply abandoned their baggage train and fled headlong through the Darial Pass to safety.[102][103] In the aftermath of this campaign, Maslama was replaced yet again by al-Jarrah. For all his energy, Maslama's campaigning failed to produce the desired results: by 729, the Arabs had lost control of northeastern Transcaucasia and been thrust once more on the defensive, with al-Jarrah again having to defend Adharbayjan against a Khazar invasion.[102][104][105]

Battle of Ardabil and the Arab reaction

In 729/730, al-Jarrah returned to the offensive through Tiflis and the Darial Pass. Ibn al-Athir reports that he reached as far as the Khazar capital, al-Bayda, on the Volga, but no other source mentions this. Modern historians are generally sceptical of this claim, considering as improbable, and possibly resulting from a confusion with other events.[105][106][107] Whatever their true scope, al-Jarrah's attacks were followed by a massive Khazar invasion,[e] reportedly of 300,000 men, which forced the Arabs to retreat south of the Caucasus once again to defend Albania.[109][107]

It is unclear whether the Khazar invasion came through the Darial Pass or the Caspian Gates or both, and different commanders are mentioned in charge of the Khazar forces: the Arab sources claim that the invasion was led by Barjik, the khagan's son, while Łewond gives the name Tar'mach for the Khazar commander.[107][110][111] Al-Jarrah appears to have dispersed some of his forces, while he withdrew his main army to Bardha'a and then to Ardabil.[109] Ardabil was the capital of Adharbayjan, and the mass of the Muslim settlers and their families, some 30,000 in total, lived within its walls.[107] Well informed of the Arab dispositions by the prince of Iberia, the Khazars managed to move around al-Jarrah and attack Warthan. Al-Jarrah rushed to assist the town, but next he is recorded as being again at Ardabil, where he confronted the main Khazar army.[109][112]

There, after a three-day battle on 7–9 December 730, al-Jarrah's army of 25,000 was all but annihilated by the Khazars.[113][114][112] Al-Jarrah was among the fallen, and command passed to his brother al-Hajjaj, who was unable to prevent the sacking of Ardabil. The 10th-century historian Agapius of Hierapolis reports that the Khazars took as many as 40,000 prisoners from the city, al-Jarrah's army, and the surrounding countryside. The Khazars raided the province at will, sacking Ganza and attacking other settlements, with some detachments reaching as far as Mosul in the northern Jazira, adjacent to the Umayyad metropolitan province of Syria.[115][116][117]

The defeat at Ardabil was a major shock to the Muslims, who for the first time faced an enemy penetrating so deep within the borders of the Caliphate, and became known even in Byzantium.[115][118] Caliph Hisham once more appointed Maslama to command against the Khazars as governor of Armenia and Adharbayjan. Until Maslama could gather enough forces, the veteran military leader Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi was sent to stem the Khazar invasion.[119][120][121] Equipped with a lance reportedly used at the Battle of Badr as a standard for his army and with 100,000 dirhams to recruit men, Sa'id went to Raqqah. The forces he could muster immediately were apparently small, but he nevertheless set out to meet the Khazars, possibly going against orders to maintain a defensive stance. On the way he encountered refugees from Ardabil and enlisted them into his army, but had to pay each of them ten gold dinars to persuade them.[115][120]

Sa'id was fortunate: after their victory at Ardabil, the Khazars had dispersed in small detachments, plundering the countryside, and the Arabs were able to defeat them in detail.[121] Sa'id first recovered Akhlat on Lake Van, then moved northeast to Bardha'a and south again to relieve the siege of Warthan. Near Bajarwan, Sa'id came upon a 10,000-strong Khazar army, which he defeated in a surprise night attack, killing most of the Khazars, and rescuing the 5,000 Muslim prisoners they had with them, among them al-Jarrah's daughter. The surviving Khazars fled north, with Sa'id in pursuit.[122][119][123] The Muslim sources record a number of other, heavily embellished exploits by Sa'id against improbably large Khazar armies; in one of them, Barjik is claimed to have been killed in single combat with the Umayyad general. Their details are generally judged to be "romance rather than history", according to the British orientalist Douglas M. Dunlop, but may reflect contemporary, though imaginative, retellings of the actual events, and are indicative of Sa'id's success against the Khazars.[124][123] According to Blankinship, "The various battles fought and rescues of Muslim prisoners achieved by Sa'id in these sources seem to all go back to a single battle near Bajarwan".[125]

Sa'id's unexpected successes angered Maslama; as Łewond writes, Sa'id had already won the war and taken what glory and booty there was to be had. As a result, Sa'id was relieved of his command in early 731 and even imprisoned for a while at Qabala and Bardha'a, charged with endangering the army in contravention of his express orders. Sa'id was released and rewarded only after the Caliph himself intervened on his behalf.[126][127][128]

Establishment of an Arab garrison town at Derbent

Maslama took command at the head of a large army, and immediately took the offensive. He restored the provinces of Albania to Muslim allegiance after meting out exemplary punishment to the inhabitants of Khaydhan, who resisted his advance, and reached Derbent, where he found a Khazar garrison of 1,000 men with their families installed. [128][129] Leaving al-Harith ibn Amr al-Ta'i at Derbent, Maslama advanced north. Although the details of this campaign in the sources may be confused with that of 728, it appears that he took Khamzin, Balanjar, and Samandar before being forced to retreat again after a confrontation with the bulk of the Khazar army under the khagan himself. Leaving their campfires burning, the Arabs withdrew in the middle of the night, and in a series of forced marches covering twice the usual distance, reached Derbent. The Khazars shadowed Maslama's march south and attacked him near Derbent, but the Arab army, augmented by local levies, resisted their onslaught until a small picked force attacked the khagan's tent and wounded the Khazar ruler himself. Taking heart, the Muslims attacked and defeated the Khazars.[130][131][132] It is possibly this battle or campaign in which Barjik was killed.[133][134]

Taking advantage of his victory, Maslama evicted the Khazars from Derbent by poisoning their water supply. He then re-founded the city as a military colony, restoring its fortifications and garrisoning it with 24,000 mostly Syrian troops divided into quarters by the districts (jund) of their origin.[133][135][136] Leaving his relative Marwan ibn Muhammad (later to become the last Umayyad caliph in 744–750) in command at Derbent, Maslama returned with the rest of his army (mostly the favoured Jaziran and Qinnasrini contingents) south of the Caucasus for the winter, while the Khazars re-occupied their abandoned towns.[133][135][137] Despite the capture of Derbent, Maslama's record was apparently unsatisfactory for Hisham, who replaced his brother in March 732 with Marwan ibn Muhammad.[133]

In the summer of 732, Marwan led 40,000 men north into Khazar lands. The accounts of this campaign are confused: Ibn A'tham records that he reached Balanjar and returned to Derbent with much captured livestock, but the campaign also suffered from heavy rainfall and mud. This is strongly reminiscent of the descriptions of Maslama's expeditions in 728 and 731, and its veracity is open to doubt. Ibn Khayyat on the other hand reports that Marwan led a far more limited campaign on the country immediately to the north of Derbent and then retired there to spend the winter.[138][139] Marwan was more active in the south, where he raised Ashot III Bagratuni to the position of presiding prince of Armenia, effectively granting the country broad autonomy in exchange for the service of its soldiers alongside the Caliphate's armies. This unique concession points, according to Blankinship, to the worsening manpower crisis faced by the Caliphate.[140][141] At about the same time, the Khazars and Byzantines strengthened their ties and formalized their alliance against their common enemy with the marriage of Constantine V to the Khazar princess Tzitzak.[142][143]

Marwan's invasion of Khazaria and end of the war

After Marwan's 732 expedition, a period of quiet set in. Marwan was replaced as governor of Armenia and Adharbayjan in spring 733 by Sa'id al-Harashi, but he undertook no campaigns during the two years of his governorship.[139][144] Blankinship attributes this inactivity to the exhaustion of the Arab armies and draws a parallel with the contemporaneous quiet phase in Transoxiana in 732–734, where the Arabs had also suffered a series of costly defeats at the hands of another Turkic steppe power, the Türgesh.[145] In the meantime, Marwan is reported to have gone before Caliph Hisham and remonstrated against the policy followed in the Caucasus, recommending that he himself be sent to deal with the Khazars, with full authority and an army of 120,000 men. When Sa'id requested to be relieved due to his failing eyesight, Hisham appointed Marwan to replace him.[137][139]

Marwan returned to the Caucasus in c. 735, determined to launch a decisive blow against the Khazars, but it appears that he too was unable to launch anything but local expeditions for some time. He established a new base of operations at Kasak, some twenty parsangs from Tiflis and forty from Bardha'a, but his initial expeditions were against minor local potentates.[146][147] Indeed, Agapius and the 12th-century historian Michael the Syrian record that the Arabs and the Khazars concluded peace during this period, information which Muslim sources ignore or explain as a short-lived ruse by Marwan designed to gain time for his preparations and mislead the Khazars as to his intentions.[148][145]

In the meantime, Marwan consolidated his rear. In 735, the Umayyad general captured three fortresses in Alania, near the Darial Pass, and the ruler of a North Caucasian principality, Tuman Shah, who was restored to his lands by the Caliph as a client ruler. In the next year, Marwan campaigned against another local prince, Wartanis, whose castle was seized and its defenders killed despite their surrender; Wartanis himself tried to flee, but was captured and executed by the inhabitants of Khamzin.[147] Marwan also subdued the Armenian factions who were hostile to the Arabs and their client Ashot. He then pushed into Iberia, driving its ruler to seek refuge in the fortress of Anakopia on the Black Sea coast, in the Byzantine protectorate of Abkhazia. Marwan laid siege to Anakopia itself, but he was forced to retire due to the outbreak of dysentery among his troops.[149] His cruelty during the invasion of Iberia earned him the nickname 'the Deaf' from the Iberians.[137]

Marwan prepared a massive strike against the Khazars for 737, intended to end the war for good. Marwan apparently went to Damascus in person to persuade Hisham to back this project and was successful: the 10th-century historian Bal'ami claims that his army numbered 150,000 men, comprising regular forces of Syria and the Jazira, as well as volunteers for the jihad, Armenian troops under Ashot Bagratuni, and even armed camp followers and servants. Whatever the real size of Marwan's army, it was a huge force and certainly the largest ever sent against the Khazars.[149][148][150] Marwan's attack was launched from two directions at once: 30,000 men (including most of the levies from the Caucasian principalities) under the governor of Derbent, Asid ibn Zafir al-Sulami, advanced north along the coast of the Caspian Sea, while Marwan himself with the bulk of his forces crossed the Darial Pass. The invasion met little resistance; the Arab sources report that Marwan had deliberately detained the Khazar envoy and only let him go with a declaration of war once he was deep in Khazar territory. The two Arab armies converged on Samandar, where a great review was held; according to Ibn A'tham, the troops were issued new clothing in white—the dynastic colour of the Umayyads—as well as new spears.[149][150][151] From there Marwan pushed on, reaching, according to some Arab sources, the Khazar capital of al-Bayda on the Volga. The khagan withdrew towards the Ural Mountains, but left behind a considerable force to protect the capital.[152][153] This was a "spectacularly deep penetration", according to Blankinship, but of little strategic value: the 10th-century travellers Ibn Fadlan and Istakhri describe the Khazar capital in their time as little more than a large encampment, and there is no evidence that it had been larger or more urbanized in the past.[154]

The subsequent course of the campaign is only provided by Ibn A'tham and the sources drawn from his work.[156][f] According to this account, Marwan ignored al-Bayda and pursued the khagan north along the west bank of the Volga, while the Khazar army, under the tarkhan (one of the highest dignitaries in Turkic states), shadowed the Arab advance from the other shore. The Arabs attacked a people called Burtas, whose territory extended up to that of the Volga Bulgars and who were Khazar subjects,[g] taking 20,000 families (or 40,000 persons, in other accounts) captive.[153][156][159] As the Khazars avoided battle, Marwan sent a detachment of 40,000 troops across the Volga under al-Kawthar ibn al-Aswad al-Anbari, which surprised the Khazars in a swamp. In the ensuing battle, the Arabs killed 10,000 Khazars, including the tarkhan, and took 7,000 captives.[156][159] [160]

This appears to have been the only fighting of the campaign between Arabs and Khazars,[156][161] and soon after, the Khazar khagan himself is said to have requested peace. Marwan reportedly offered "Islam or the sword", whereupon the khagan agreed to convert to Islam. Two faqihs were sent to instruct him on the details of the faith—the prohibition on consuming wine, pork, and unclean meat are specifically mentioned.[162][158][163] Marwan also took with him large numbers of Slav and Khazar captives, whom he resettled in the eastern Caucasus: some 20,000 Slavs were settled at Kakheti, according to al-Baladhuri, while the Khazars were resettled at al-Lakz. Soon after, the Slavs killed their appointed governor and fled north, but Marwan rode after them and killed them.[163][164][165]

Marwan's 737 expedition was the climax of the Arab–Khazar wars, but its actual results were meagre. Although the Arab campaigns after Ardabil may indeed have discouraged the Khazars from further warfare,[164] any recognition of Islam or of Arab supremacy by the khagan was evidently conditional upon the presence of Arab troops deep in Khazar territory, and such presence could not be sustained for long.[163][166] Furthermore, the credibility of the conversion of the khagan to Islam is disputed: al-Baladhuri's account, which probably is closest to the original sources, suggests that it was not the khagan but a minor lord who converted to Islam, and was placed in charge of the Khazars at al-Lakz. According to Blankinship, this is an indication of the implausibility of the conversion of the khagan, since the Khazar Muslim converts had to be removed to safety in Umayyad territory.[156]

The conversion of the khagan is also contradicted by the fact that the Khazar court is known to have embraced Judaism as its official faith. Dunlop placed this as early as c. 740, but the process was apparently a gradual one: according to historical sources, it was under way in the last decades of the 8th century, and numismatic evidence shows that by the 830s it was likely complete.[167][168] The conversion was apparently mostly confined to the Khazar elites, while Christianity, Islam, and even pagan beliefs remained widespread among the common people.[169] As a result, many modern scholars have adopted the thesis that the Khazar elites' conversion to Judaism was a means of stressing their own identity as separate from, and avoiding assimilation by, the Christian Byzantine and the Muslim Arab empires with which they were in contact, and a direct result of the events of 737.[170][171]

Aftermath and impact of the Second Arab–Khazar War

Whatever the real events of Marwan's campaigns, warfare between the Khazars and the Arabs ceased for more than two decades after 737.[141] Arab military activity in the Caucasus continued until 741, with Marwan launching repeated expeditions against the various principalities in the area of modern Dagestan.[h][174][175] Blankinship emphasizes that these campaigns appear to have been closer to raids, designed to seize plunder and extract tribute to ensure the upkeep of the Arab army, rather than attempts at permanent conquest.[176] On the other hand, Dunlop considered that Marwan came "within an ace of succeeding" in his conquest of Khazaria, and that he "apparently intended to resume operations against the khagan at a later date", but this never materialized.[177]

Despite the Umayyads' success at establishing a more or less stable frontier anchored at Derbent,[69][176] they were unable to push any further, despite repeated efforts, in the face of vigorous Khazar resistance. Dunlop drew parallels between the Umayyad–Khazar confrontation at the Caucasus and that between the Umayyads and the Franks at roughly the same time across the Pyrenees that ended in the Battle of Tours, noting that, like the Franks in the west, the Khazars played a crucial role in stemming the tide of the early Muslim conquests.[178] According to Golden, during the long conflict the Arabs "had been able to maintain their hold over much of Transcaucasia", but he also notes that despite occasional Khazar raids, this "had never really been seriously threatened". On the other hand, in their failure to push the border north of Derbent, the Arabs were clearly "reaching the outer limits of their imperial drive".[179]

Blankinship also highlights the limited gains made by the Caliphate in the Second Arab–Khazar War as disproportionate to the resources expended: Arab control was in reality limited to the lowlands and coast, and the land itself was too poor to recompense the Umayyad treasury. More importantly, the need to maintain the large garrison at Derbent further depleted the already overstretched Syro-Jaziran army, the main pillar of the Umayyad regime.[176] Eventually, the weakening of the Syrian army through its dispersion across the various fronts of the Caliphate would be the major factor in the fall of the Umayyad dynasty during the Muslim civil wars of the 740s and the Abbasid Revolution that followed them.[180]

Balanjar is no longer mentioned after the Arab–Khazar wars, but a people called Baranjar is later recorded as living in Volga Bulgaria, likely the descendants of the original tribe that had given the town its name, and that had resettled there as a result of the wars.[181] Many Soviet and Russian archaeologists and historians, such as Murad Magomedov and Svetlana Pletnyova, consider the emergence of the Saltovo-Mayaki culture in the steppe region between the Don and the Dnieper Rivers during the 8th century to have been the result of the Arab–Khazar conflict, as Alans from the North Caucasus were resettled there by the Khazars.[182]

Later conflicts

Abbasid Caliphate Khazar Khaganate Byzantine Empire Carolingian Empire

The Khazars resumed their raids on Muslim territory after the Abbasid succession in 750, reaching deep into Transcaucasia. Although by the 9th century the Khazars had re-consolidated their control over Dagestan almost to the gates of Derbent itself, they never seriously attempted to challenge Muslim control of the southern Caucasus.[163] As Noonan writes, "the Khazar-Arab Wars ended in a stalemate".[183]

The first conflict between the Khazars and the Abbasids resulted from a diplomatic manoeuvre by the Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775). Attempting to strengthen the Caliphate's ties with the Khazars, in c. 760 he ordered his governor of Armenia, Yazid al-Sulami, to marry a daughter of the khagan Baghatur. The marriage indeed took place amidst much celebration, but she died in childbirth two years later, along with her infant child. The khagan suspected the Muslims of poisoning his daughter, and launched devastating raids south of the Caucasus in 762–764. Under the leadership of a Khwarezmian tarkhan named Ras, the Khazars devastated Albania, Armenia, and Iberia, where they captured Tiflis. Yazid himself managed to escape capture, but the Khazars returned north with thousands of captives and much booty.[163][184] A few years later, however, in 780, when the deposed Iberian ruler Nerse tried to induce the Khazars to campaign against the Abbasids and restore him to his throne, the khagan refused. This was probably the result of a brief period of anti-Byzantine orientation in Khazar foreign policy, resulting from disputes between the two powers in the Crimea. During the same period, the Khazars helped Leon II of Abkhazia throw off Byzantine overlordship.[163][185]

Peace reigned in the Caucasus between Arabs and Khazars until 799, when the last major Khazar attack into Transcaucasia took place. Chroniclers again attribute this attack to a failed marriage alliance.[163] According to Georgian sources, the khagan desired to marry the beautiful Shushan, daughter of Prince Archil of Kakheti (r. 736–786), and he sent his general Bulchan to invade Iberia and capture her. Most of the central region of K'art'li was occupied, and Prince Juansher (r. 786–807) was taken off into captivity for a few years, but rather than be captured, Shushan committed suicide, and the furious khagan had Bulchan executed.[186] According to Semyonov, however, these events are misdated, and should be attributed to the great Khazar invasion of 730, while Juansher's seven-year captivity coincides with the end of the Second Arab–Khazar War.[187] Arab chroniclers, on the other hand, attribute this to the plans of the Abbasid governor al-Fadl ibn Yahya (one of the famous Barmakids) to marry one of the khagan's daughters, who died on her journey south, while a different story is reported by al-Tabari, whereby the Khazars were invited to attack by a local Arab magnate in retaliation against the execution of his father, the governor of Derbent, by the general Sa'id ibn Salm. According to the Arab sources, the Khazars then raided as far as the Araxes, necessitating the dispatch of troops under Yazid ibn Mazyad, as the new governor of Transcaucasia, with more forces under Khuzayma ibn Khazim in reserve.[163][185][188]

Despite these episodes of warfare, the presence of hoards of Arab coins in Eastern Europe suggests that a significant trade route developed via the Caucasus in the second half of the 8th century.[189] Arabs and Khazars continued to clash sporadically in the North Caucasus in the 9th and 10th centuries, but warfare was localized and of far lower intensity than the great wars of the 8th century. Thus the Ottoman historian Münejjim Bashi records a period of warfare lasting from c. 901 until 912, perhaps linked to the Caspian raids of the Rus' at about the same time, whom the Khazars allowed to pass through their lands unhindered.[190] Indeed, for the Khazars, peace on the southern border became the more important as new threats emerged in the steppes to challenge their hegemony.[191] The Khazar threat receded with the progressive collapse of Khazar power in the 10th century and defeats at the hands of the Rus' and other Turkic nomads like the Oghuz Turks. The Khazar realm contracted to its core around the lower Volga, and became removed from reach of the Arab Muslim principalities of the Caucasus. Thus Ibn al-Athir's reports of a war between the Shaddadids of Ganja with the "Khazars" in 1030 probably refers to the Georgians instead. In the end, the last Khazars found refuge among their former enemies. Münejjim Bashi records that in 1064, "the remnants of the Khazars, consisting of three thousand households, arrived in Qahtan [somewhere in Dagestan] from the Khazar territory. They rebuilt it and settled in it".[192]

Notes

- ^ On suggestions about its location, cf. Semyonov 2008, pp. 283–284

- ^ For more details, cf. Albrecht 2016 and the literature referenced there.

- ^ According to Thomas S. Noonan, the significance of this marriage alliance should not be overestimated: Byzantium was even more hard-pressed by the Arab attacks than the Khazars, both sides could provide little tangible help to one another,[44] and there is no evidence of any further Byzantine–Khazar relations after this event until half a century later.[45] Noonan comments that the marriage was "purely symbolic, a gesture of solidarity and no more".[44]

- ^ The task of facing the Khazars during the Second Arab–Khazar War fell upon the Umayyad governors of Armenia and Adharbayjan, the two provinces being governed in tandem at the time, and usually combined with the governorship of the Jazira provice.[76][77]

- ^ Łewond reports that the Khazar invasion was preceded by the death of the khagan, leaving his widow Parsbit as ruler over the Khazars.[105] Consequently, Semyonov suggests that al-Jarrah's raid against al-Bayda may indeed have reached the city, or at least succeeded in killing the khagan, and that the subsequent invasion was launched as a campaign of vengeance.[108]

- ^ Artamonov notes that most Arabic sources about the campaign are vague and provide little detail, while Armenian historians only mention Arab attacks on the lands of the North Caucasus Huns, and the capture of Barachan (Balanjar).[157]

- ^ According to medieval Arab geographers, the land of the Burtas was 15–20 days north of al-Bayda, putting it approximately in modern Mordovia.[158]

- ^ The Arabic sources list expeditions to extract tribute (in the form of a levy of slaves and annual grain supplies to Derbent) as well as impose obligations of military assistance against the principalities of Sarir, Ghumik, Khiraj or Khizaj, Tuman, Sirikaran, Khamzin, Sindan (also found as Sughdan or Masdar), Layzan or al-Lakz, Tabarsaran, Sharwan, and Filan.[172][173]

References

- ^ a b c Blankinship 1994, p. 106.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 41, 58.

- ^ a b Brook 2006, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Mako 2010, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Mako 2010, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Brook 2006, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Kemper 2013.

- ^ Brook 2006, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Brook 2006, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Noonan 1992, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Barthold & Golden 1978, p. 1173.

- ^ Golden 1980, pp. 221–222, 225.

- ^ Mako 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Mako 2010, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Wasserstein 2007, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 11.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 11–18.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 126.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, pp. 23–25, 29.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Golden 1992, pp. 237–238.

- ^ a b Zhivkov 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 108.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, pp. 9, 13.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, p. 10.

- ^ a b Semyonov 2010, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Blankinship 1994, p. 124.

- ^ a b Semyonov 2010, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Lilie 1976, p. 157.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 107.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 109.

- ^ Wasserstein 2007, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Mako 2010, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Wasserstein 2007, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 149–154.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 157–160.

- ^ a b Noonan 1992, p. 128.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 113.

- ^ Mako 2010, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b c Gocheleishvili 2014.

- ^ Canard 1960, pp. 635–636.

- ^ Canard 1960, pp. 636–637.

- ^ Minorsky 1960, p. 190.

- ^ Frye 1960, p. 660.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Noonan 1992, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 51–54.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, p. 179.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Mako 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 57.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 178.

- ^ a b Noonan 1992, p. 179.

- ^ Wasserstein 2007, p. 375.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Noonan 1992, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 181.

- ^ a b Noonan 1992, p. 182.

- ^ a b Cobb 2010, p. 236.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e Brook 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 203.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 205.

- ^ Semyonov 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 40, 52–53.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Semyonov 2008, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b c d e Blankinship 1994, p. 122.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 206.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c Dunlop 1954, p. 65.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, p. 207.

- ^ Semyonov 2008, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 207–209.

- ^ a b c Dunlop 1954, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e f g Artamonov 1962, p. 209.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Dunlop 1954, p. 67.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Semyonov 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Dunlop 1954, p. 68.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 125, 149.

- ^ a b c Artamonov 1962, p. 211.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c d Blankinship 1994, p. 149.

- ^ Semyonov 2008, pp. 286–293.

- ^ a b c Dunlop 1954, p. 69.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Semyonov 2008, p. 286.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b c Blankinship 1994, p. 150.

- ^ Brook 2006, p. 128.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Dunlop 1954, p. 71.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, p. 214.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 324 (note 34).

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 215.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 74–76.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 216–217.

- ^ a b c d Blankinship 1994, p. 152.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 79 (note 96).

- ^ a b Dunlop 1954, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Artamonov 1962, p. 218.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b c Dunlop 1954, p. 80.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 153.

- ^ a b Cobb 2010, p. 237.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 171.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b Dunlop 1954, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Blankinship 1994, p. 172.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Brook 2006, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Blankinship 1994, p. 173.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b Artamonov 1962, p. 222.

- ^ a b Dunlop 1954, p. 83.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barthold & Golden 1978, p. 1174.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 174.

- ^ Brook 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Artamonov 1962, p. 223.

- ^ Golden 2007, pp. 139–151–157, 158–159.

- ^ Brook 2006, pp. 106–114.

- ^ Golden 2007, pp. 135–150.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Golden 2007, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 174–175, 331–332 (notes 36–47).

- ^ Artamonov 1962, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 85, 86–87.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b c Blankinship 1994, p. 175.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 46–47, 87.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 238.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 223–225, 230–236.

- ^ Golden 1980, pp. 144, 221–222.

- ^ Zhivkov 2015, pp. 186 (esp. note 71), 221–222.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 126.

- ^ Brook 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b Brook 2006, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Brook 2006, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Semyonov 2008, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Bosworth 1989, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Noonan 1984, p. 172.

- ^ Barthold & Golden 1978, pp. 1175–1176.

- ^ Noonan 1992, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Barthold & Golden 1978, p. 1176.

Sources

- Albrecht, Sarah (2016). "Dār al-Islām and dār al-ḥarb". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Artamonov, M. I. (1962). История хазар [History of the Khazars] (in Russian). Leningrad: Издательство Государственного Эрмитажа. OCLC 490020276.

- Barthold, W. & Golden, P. (1978). "K̲h̲azar". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1172–1181. OCLC 758278456.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXX: The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Mūsā al-Hādī and Hārūn al-Rashīd, A.D. 785–809/A.H. 169–192. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-564-4.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria, Second Edition. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7425-4982-1.

- Canard, M. (1960). "Armīniya. 2. — Armenia under Arab domination". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 635–638. OCLC 495469456.

- Cobb, Paul M. (2010). "The empire in Syria, 705–763". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 226–268. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Dunlop, Douglas M. (1954). The History of the Jewish Khazars. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 459245222.

- Frye, R. N. (1960). "Arrān". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 660–661. OCLC 495469456.

- Gocheleishvili, Iago (2014). "Caucasus, pre-900/1500". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Golden, Peter B. (1980). Khazar Studies: An Historico-Philological Inquiry into the Origins of the Khazars, Volume 1. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-1549-0.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-44703274-2.

- Golden, Peter B. (2007). "The Conversion of the Khazars to Judaism". In Peter B. Golden; Haggai Ben-Shammai; András Róna-Tas (eds.). The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives. Selected Papers from the Jerusalem 1999 International Khazar Colloquium hosted by the Ben Zvi Institute. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 373–386. ISBN 978-90-04-16042-2.

- Kemper, Michael (2013). "Daghestan". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München. OCLC 568754312.

- Mako, Gerald (2010). "The Possible Reasons for the Arab–Khazar Wars". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. 17: 45–57. ISSN 0724-8822.

- Minorsky, V. (1960). "Ad̲h̲arbayd̲jān". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 188–191. OCLC 495469456.

- Noonan, Thomas S. (1984). "Why Dirhams First Reached Russia: The Role of Arab-Khazar Relations in the Development of the Earliest Islamic Trade with Eastern Europe". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. 4: 151–282. ISSN 0724-8822.

- Noonan, Thomas S. (1992). "Byzantium and the Khazars: a special relationship?". In Shepard, Jonathan; Franklin, Simon (eds.). Byzantine Diplomacy: Papers from the Twenty-Fourth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Cambridge, March 1990. Aldershot, England: Variorium. pp. 109–132. ISBN 978-0860783381.

- Semyonov, Igor G. (2008). "Эпизоды биографии хазарского принца Барсбека" [Biographical episodes of the Khazar prince Barsbek] (PDF). Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual International Conference on Jewish Studies, Part 2 (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 282–297. ISBN 978-5-8125-1212-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Semyonov, Igor G. (2010). "Военная тактика хазарской армии в период войны против Арабского халифата в 706—737 годы" [Military tactics of the Khazar army in the period of the war against the Arab caliphate in 706–737] (PDF). Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual International Conference on Jewish Studies, Vol. II (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 7–15. ISBN 978-5-9860-4253-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wasserstein, David J. (2007). "The Khazars and the World of Islam". In Peter B. Golden; Haggai Ben-Shammai; András Róna-Tas (eds.). The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives. Selected Papers from the Jerusalem 1999 International Khazar Colloquium hosted by the Ben Zvi Institute. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 373–386. ISBN 978-90-04-16042-2.

- Zhivkov, Boris (2015). Khazaria in the Ninth and Tenth centuries. Translated by Daria Manova. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29307-6.