Poverty: Difference between revisions

Van helsing (talk | contribs) |

→Measuring poverty: This is pretty much just moving things around, trying for a more logical order. I've also corrected that the US does *not* actually use a relative poverty standard. |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

When measured, poverty may be [[absolute poverty|absolute]] or [[relative poverty]]. Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. An example of an absolute measurement would be the percentage of the population eating less food than is required to sustain the human body (approximately 2000-2500 [[calorie]]s per day for an adult male). |

When measured, poverty may be [[absolute poverty|absolute]] or [[relative poverty]]. Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. An example of an absolute measurement would be the percentage of the population eating less food than is required to sustain the human body (approximately 2000-2500 [[calorie]]s per day for an adult male). |

||

| ⚫ | Relative poverty, in contrast, views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context. In many developed countries the official definition of poverty used for statistical purposes is based on relative income. A relative measurement would be to compare the total wealth of the poorest one-third of the population with the total wealth of richest 1% of the population. In this case, the number of people counted as poor could increase while their income rise. There are several different income inequality metrics. One example is the Gini coefficient. Many critics argue that such poverty statistics measure inequality rather than material deprivation or hardship. |

||

| ⚫ | The [[World Bank Group|World Bank]] defines ''[[extreme poverty]]'' as living on less than US$ ([[Purchasing power parity|PPP]]) 1 per day, and ''moderate poverty'' as less than $2 a day. It has been estimated that in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day. The proportion of the [[developing world]]'s population living in extreme economic poverty has fallen from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001. Much of the improvement has occurred in East and South Asia. In Sub-Saharan Africa GDP/capita shrank with 14 percent and extreme poverty increased from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001. Other regions have seen little or no change. In the early 1990s the transition economies of Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income. Poverty rates rose to 6 percent at the end of the decade before beginning to recede. <ref>[http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/0,,contentMDK:20153855~menuPK:373757~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:336992,00.html Worldbank.org reference]</ref> There are various criticisms of these measurements.<ref>[http://socialanalysis.org/ Institute of Social Analysis]</ref> |

||

The main [[poverty line]] used in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ([[OECD]]) and the [[European Union]], takes the relative poverty route, and is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 50% of the median household income. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The [[World Bank Group|World Bank]] takes the absolute poverty route and defines ''[[extreme poverty]]'' as living on less than US$ ([[Purchasing power parity|PPP]]) 1 per day, and ''moderate poverty'' as less than $2 a day. It has been estimated that in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day. The proportion of the [[developing world]]'s population living in extreme economic poverty has fallen from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001. Much of the improvement has occurred in East and South Asia. In Sub-Saharan Africa GDP/capita shrank with 14 percent and extreme poverty increased from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001. Other regions have seen little or no change. In the early 1990s the transition economies of Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income. Poverty rates rose to 6 percent at the end of the decade before beginning to recede. <ref>[http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/0,,contentMDK:20153855~menuPK:373757~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:336992,00.html Worldbank.org reference]</ref> There are various criticisms of these measurements.<ref>[http://socialanalysis.org/ Institute of Social Analysis]</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on |

||

The US government also uses an absolute poverty line. It was created in 1963-64 and was based on the dollar costs of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's "economy food plan" multiplied by a factor of three. The multiplier was based on research showing that food costs then accounted for about one third of the total money income. This one-time calculation has since been annually updated for inflation.<ref>[http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/faq.shtml US Department of Human Services]-FAQ Poverty Guidelines and Poverty</ref> |

|||

Some have criticized the US's line as arbitrarily high, objecting, for instance, to the fact that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 46% of those below the country's official poverty line own their own home (with the average poor person's home having three bedrooms, with one and a half baths, and a garage).<ref>Rector, Robert E. and Johnson, Kirk A., [http://www.fullemployment.org/Understanding%20Poverty%20in%20America.pdf ''Understanding Poverty in America'']Executive Summary, Heritage Foundation, January 15, 2004 No. 1713</ref> |

|||

Some people object that the income measures above are misleading because they are usually based on a person's yearly income and frequently take no account of total wealth. |

|||

[[Income inequality]] for the world as a whole is diminishing. A 2002 study by [[Xavier Sala-i-Martin]] finds that this is driven mainly, but not fully, by the extraordinary growth rate of the incomes of the 1.2 billion Chinese citizens. However, unless Africa achieves economic growth, then China, India, the OECD and the rest of middle-income and rich countries will diverge away from it, and global inequality will rise. Thus, the economic growth of the African continent should be the priority of anyone concerned with increasing global income inequality.<ref>[http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/chapters/htm/index2007_chap1.cfm Global Inequality Fades as the Global Economy Grows] 2007 Index of Economic Freedom. Xavier Sala-i-Martin]</ref><ref>[http://www.columbia.edu/~xs23/papers/GlobalIncomeInequality.htm The Disturbing "Rise" of Global Income Inequality] by Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2001</ref> |

[[Income inequality]] for the world as a whole is diminishing. A 2002 study by [[Xavier Sala-i-Martin]] finds that this is driven mainly, but not fully, by the extraordinary growth rate of the incomes of the 1.2 billion Chinese citizens. However, unless Africa achieves economic growth, then China, India, the OECD and the rest of middle-income and rich countries will diverge away from it, and global inequality will rise. Thus, the economic growth of the African continent should be the priority of anyone concerned with increasing global income inequality.<ref>[http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/chapters/htm/index2007_chap1.cfm Global Inequality Fades as the Global Economy Grows] 2007 Index of Economic Freedom. Xavier Sala-i-Martin]</ref><ref>[http://www.columbia.edu/~xs23/papers/GlobalIncomeInequality.htm The Disturbing "Rise" of Global Income Inequality] by Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2001</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Indicators other than money can be used as signals for poverty, and several of them are improving. [[Life expectancy]] has greatly increased in the developing world since [[World War II|WWII]] and is starting to close the gap to the developed world where the improvement has been smaller. Even in Sub-Saharan Africa, the least developed region, life expectancy increased from 30 years before World War II to a peak of about 50 years before the HIV pandemic and other diseases started to force it down to the current level of 47 years. [[Child mortality]] has decreased in every developing region of the world<ref>[http://www.theglobalist.com/DBWeb/StoryId.aspx?StoryId=2429 The Eight Losers of Globalization] By Guy Pfeffermann. </ref>. The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 [[kilojoule]]s) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Between 1950 and 1999, global literacy increased from 52% to 81% of the world. Women made up much of the gap: Female literacy as a percentage of male literacy has increased from 59% in 1970 to 80% in 2000. The percentage of children not in the labor force has also risen to over 90% in 2000 from 76% in 1960. There are similar trends for electric power, cars, radios, and telephones per capita, as well as the proportion of the population with access to clean water.<ref>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VC6-4F02KWN-8&_user=10&_coverDate=01%2F01%2F2005&_rdoc=1&_fmt=summary&_orig=browse&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3c12cc79f8121ee4e000396b0273a1eb World Development Volume 33, Issue 1 , January 2005, Pages 1-19, Why Are We Worried About Income? Nearly Everything that Matters is Converging]</ref> |

||

Even if poverty may be lessening for the world as a whole, it continues to be an enormous problem: |

Even if poverty may be lessening for the world as a whole, it continues to be an enormous problem: |

||

Revision as of 18:52, 17 July 2007

Poverty is understood in many senses [1]. The main understandings of the term include:

- Descriptions of material need, typically including the necessities of daily living (food, clothing, shelter, and health care). Poverty in this sense may be understood as a condition in which a person or community is deprived of, and or lacks the essentials for a minimum standard of well-being and life. These essentials may be material resources such as food, safe drinking water, and shelter, or they may be social resources such as access to information, education, health care, social status, political power,[2] or the opportunity to develop meaningful connections with other people in society.[3]

- Descriptions of social relationships and need, including social exclusion [4], dependency [5], and the ability to participate in society [6]. This would include education and information.

- Describing a (persistent) lack of income and wealth. The World Bank, for example, uses a global indicator of incomes or $1 or $2 a day. In relative terms disparities in income or wealth income disparities are seen as an indicator of poverty and the condition of poverty is linked to questions of scarcity and distribution of resources and power.

The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor" [7], based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty. These include

- precarious livelihoods

- excluded locations

- physical limitations

- gender relationships

- problems in social relationships

- lack of security

- abuse by those in power

- disempowering institutions

- limited capabilities, and

- weak community organisations.

Most important are those necessary for material well-being, especially food. Others of these issues relate to social rather than material issues.

Poverty may be defined by a government or organization for legal purposes, see Poverty threshold.

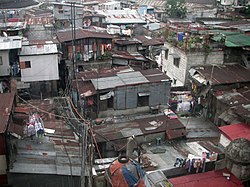

Poverty may be seen as the collective condition of poor people, or of poor groups, and in this sense entire nation-states are sometimes regarded as poor. A more neutral term is developing nations. Although the most severe poverty is in the developing world, there is evidence of poverty in every region. In developed countries examples include homeless people and ghettos.

Poverty is also a type of religious vow, a state that may be taken on voluntarily in keeping with practices of piety.

Measuring poverty

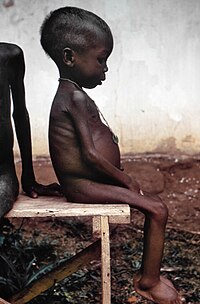

When measured, poverty may be absolute or relative poverty. Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. An example of an absolute measurement would be the percentage of the population eating less food than is required to sustain the human body (approximately 2000-2500 calories per day for an adult male).

Relative poverty, in contrast, views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context. In many developed countries the official definition of poverty used for statistical purposes is based on relative income. A relative measurement would be to compare the total wealth of the poorest one-third of the population with the total wealth of richest 1% of the population. In this case, the number of people counted as poor could increase while their income rise. There are several different income inequality metrics. One example is the Gini coefficient. Many critics argue that such poverty statistics measure inequality rather than material deprivation or hardship.

The main poverty line used in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union, takes the relative poverty route, and is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 50% of the median household income.

The World Bank takes the absolute poverty route and defines extreme poverty as living on less than US$ (PPP) 1 per day, and moderate poverty as less than $2 a day. It has been estimated that in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day. The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty has fallen from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001. Much of the improvement has occurred in East and South Asia. In Sub-Saharan Africa GDP/capita shrank with 14 percent and extreme poverty increased from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001. Other regions have seen little or no change. In the early 1990s the transition economies of Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income. Poverty rates rose to 6 percent at the end of the decade before beginning to recede. [8] There are various criticisms of these measurements.[9]

The US government also uses an absolute poverty line. It was created in 1963-64 and was based on the dollar costs of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's "economy food plan" multiplied by a factor of three. The multiplier was based on research showing that food costs then accounted for about one third of the total money income. This one-time calculation has since been annually updated for inflation.[10]

Some have criticized the US's line as arbitrarily high, objecting, for instance, to the fact that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 46% of those below the country's official poverty line own their own home (with the average poor person's home having three bedrooms, with one and a half baths, and a garage).[11]

Some people object that the income measures above are misleading because they are usually based on a person's yearly income and frequently take no account of total wealth.

Income inequality for the world as a whole is diminishing. A 2002 study by Xavier Sala-i-Martin finds that this is driven mainly, but not fully, by the extraordinary growth rate of the incomes of the 1.2 billion Chinese citizens. However, unless Africa achieves economic growth, then China, India, the OECD and the rest of middle-income and rich countries will diverge away from it, and global inequality will rise. Thus, the economic growth of the African continent should be the priority of anyone concerned with increasing global income inequality.[12][13]

Indicators other than money can be used as signals for poverty, and several of them are improving. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since WWII and is starting to close the gap to the developed world where the improvement has been smaller. Even in Sub-Saharan Africa, the least developed region, life expectancy increased from 30 years before World War II to a peak of about 50 years before the HIV pandemic and other diseases started to force it down to the current level of 47 years. Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world[14]. The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 kilojoules) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Between 1950 and 1999, global literacy increased from 52% to 81% of the world. Women made up much of the gap: Female literacy as a percentage of male literacy has increased from 59% in 1970 to 80% in 2000. The percentage of children not in the labor force has also risen to over 90% in 2000 from 76% in 1960. There are similar trends for electric power, cars, radios, and telephones per capita, as well as the proportion of the population with access to clean water.[15]

Even if poverty may be lessening for the world as a whole, it continues to be an enormous problem:

- One third of deaths - some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day - are due to poverty-related causes. That's 270 million people since 1990, the majority women and children, roughly equal to the population of the US. [16]

- Every year nearly 11 million children die before their fifth birthday.

- In 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day

- 800 million people go to bed hungry every day.

Causes of poverty

Many different factors have been cited to explain why poverty occurs. However, no single explanation has gained universal acceptance. Some possible factors include:

- Natural factors such as the climate or environment[17]

- Geographic factors, for example access to fertile land, fresh water, minerals, energy, and other natural resources. Presence or absence of natural features helping or limiting communication, such mountains, deserts, sailable rivers, or coastline. Historically, geography has prevented or slowed the spread of new technology to areas such as the Americas and Sub-Saharan Africa. The climate also limits what crops and farm animals may be used on similarly fertile lands.[18]

- On the other hand, research on the resource curse has found that countries with an abundance of natural resources creating quick wealth from exports tend to have less long-term prosperity than countries with less of these natural resources.

- Inadequate nutrition in childhood in poor nations may lead to physical and mental stunting that may lead to economic problems. (Hence, it is both a cause and an effect). For example, lack of both iodine and iron has been implicated in impaired brain development, and this can affect enormous numbers of people: it is estimated that 2 billion people (one-third of the total global population) are affected by iodine deficiency, including 285 million 6- to 12-year-old children. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged 4 and under suffer from anaemia because of insufficient iron in their diets. See also Health and intelligence.[19]

- Disease, specifically diseases of poverty: AIDS[20], malaria[21], and tuberculosis and others overwhelmingly afflict developing nations, which perpetuate poverty by diverting individual, community, and national health and economic resources from investment and productivity.[22] Further, many tropical nations are affected by parasites like malaria, schistosomiasis, and trypanosomiasis that are not present in temperate climates. The Tsetse fly makes it very difficult to use many animals in agriculture in afflicted regions.

- Poverty itself, prevents (for example) various forms of investment

- Inability to find a well-paying job (see working poor)

- Unemployment and/or underemployment

- Globalization, too much or too little.

- Lacking rule of law.[23]

- Lacking democracy.[24]

- Lacking infrastructure[25].

- Lacking health care.[26]

- Lacking equitably available education.[27]

- Government corruption.[28]

- Overpopulation and lack of access to birth control methods.[29] Note that population growth slows or even become negative as poverty is reduced due to the demographic transition.[30]

- Tax havens which tax their own citizens and companies but not those from other nations and refuse to disclose information necessary for foreign taxation. This enables large scale political corruption, tax evasion, and organized crime in the foreign nations.[31]

- Historical factors, for example imperialism and colonialism[32][33][34].

- Capitalism, Socialism, Communism, Monarchy, Fascism and Totalitarianism have all been named as causes by scholars writing from different perspectives. For example, poorly functioning property rights is seen by some as a cause of poverty[35], while socialists see the institution of property rights itself as a cause of poverty.[36]

- Lacking free trade. In particular, the very high subsidies to and protective tariffs for agriculture in the developed world. For example, almost half of the budget of the European Union goes to agricultural subsidies, mainly to large farmers and agribusinesses, which form a powerful lobby.[37] Japan gave 47 billion dollars in 2005 in subsidies to its agricultural sector,[38] nearly four times the amount it gave in total foreign aid.[39] The US gives 3.9 billion dollars each year in subsidies to its cotton sector, including 25,000 growers, three times more in subsidies than the entire USAID budget for Africa’s 500 million people.[40] This drains the taxed money and increases the prices for the consumers in developed world; decreases competition and efficiency; prevents exports by more competitive agricultural and other sectors in the developed world due to retaliatory trade barriers; and undermines the very type of industry in which the developing countries do have comparative advantages.[41]

- Lack of freedom and social oppression.

- Lack of social integration. For example, arising from immigration (see related article, Economic impact of immigration to Canada).

- Slavery

- Crime, both white-collar crime and blue-collar crime.

- Substance abuse, such as alcoholism and drug abuse.[42]

- War, including civil war, genocide, and democide.

- Brain drain

- Lack of social skills.

- Exploitation of the poor by the rich.

- Even if not exploitation in the sense of theft, the already wealthy may have easier to accumulate more wealth, for example by hiring better financial advisors.

- Matthew effect: the phenomenon, widely observed across advanced welfare states, that the middle classes tend to be the main beneficiaries of social benefits and services, even if these are primarily targeted at the poor.

- Cultural causes, which attribute poverty to common patterns of life, learned or shared within a community. For example, Max Weber argued that Protestantism contributed to economic growth during the industrial revolution.

- Individual beliefs, actions and choices.[43]

- Mental illness and disability

- Discrimination of various kinds, such as age discrimination, stereotyping[44], gender discrimination, racial discrimination.

Effects of poverty

Some effects of poverty may also be causes, as listed above, thus creating a "poverty cycle" and complicating the subject further:

- Depression[45]

- Lack of sanitation[46][47].

- Increased vulnerability to natural disasters[48][49]

- Extremism

- Hunger and starvation

- Human trafficking

- High crime rate

- Increased suicides

- Increased risk of political violence; such as terrorism, war and genocide

- Homelessness

- Lack of opportunities for employment

- Low literacy

- Social isolation

- Loss of population due to emigration.

- Increased discrimination

- Lower life expectancy

- Drug abuse

Poverty reduction

In politics, the fight against poverty is usually regarded as a social goal and many governments have — secondarily at least — some dedicated institutions or departments.

Economic growth

- The anti-poverty strategy of the World Bank depends heavily on reducing poverty through the promotion of economic growth[50]. The World Bank argues that an overview of many studies show that:

- Growth is fundamental for poverty reduction, and in principle growth as such does not affect inequality.

- Growth accompanied by progressive distributional change is better than growth alone.

- High initial income inequality is a brake on poverty reduction.

- Poverty itself is also likely to be a barrier for poverty reduction; and wealth inequality seems to predict lower future growth rates.[51]

- The Global Competitiveness Report, the Ease of Doing Business Index, and the Index of Economic Freedom are annual reports, often used in academic research, ranking the worlds nations on factors argued to increase economic growth and reduce poverty.

- Business groups see the reduction of barriers to the creation of new businesses [52], or reducing barriers for existing business, as having the effect of bringing more people into the formal economy.

- The 2007 World Bank report "Global Economic Prospects" predicts that in 2030 the number living on less than the equivalent of $1 a day will fall by half, to about 550 million. An average resident of what we used to call the Third World will live about as well as do residents of the Czech or Slovak republics today. However, much of Africa will have difficulty keeping pace with the rest of the developing world and even if conditions there improve in absolute terms, the report warns, Africa in 2030 will be home to a larger proportion of the world's poorest people than it is today.[53] However, economic growth has increased rapidly in Africa after the year 2000. [4]

Direct aid

- The government can directly help those in need. This has been applied with mixed results in most Western societies during the 20th century in what became known as the welfare state. Especially for those most at risk, such as the elderly and people with disabilities. The help can be for example monetary or food aid.

- Private charity. This is often formally encouraged within the legal system. For example, charitable trusts and tax deductions for charity.

- The Copenhagen Consensus is a listing of the most cost-effective methods for advancing global welfare.

Improving the social environment and abilities of the poor

- Subsidized housing development and urban regeneration.

- Subsidized education.

- Subsidized health care.

- Assistance in finding employment.

- Subsidized employment (see also Workfare).

- Encouragement of political participation and community organizing.

- Community practice social work.

Millennium Development Goals

Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 is a Millennium Development Goal. In addition to broader approaches, the Sachs Report (for the UN Millennium Project) [54] proposes a series of "quick wins", approaches identified by development experts which would cost relatively little but could have a major constructive effect on world poverty. The quick wins are:

- Access to information on sexual and reproductive health.

- Action against domestic violence.

- Appointing government scientific advisors in every country.

- Deworming school children in affected areas.

- Drugs for AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

- Eliminating school fees.

- Ending user fees for basic health care in developing countries.

- Free school meals for schoolchildren.

- Legislation for women’s rights, including rights to property.

- Planting trees.

- Providing soil nutrients to farmers in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Providing mosquito nets.

- Access to electricity, water and sanitation.

- Supporting breast-feeding.

- Training programs for community health in rural areas.

- Upgrading slums, and providing land for public housing.

Development aid

Most developed nations give some development aid to developing nations. The UN target for development aid is 0.7% of GDP; currently only a few nations achieve this. Some think tanks and NGOs have argued, however, that Western monetary aid often only serves to increase poverty and social inequality, either because it is conditioned with the implementation of harmful economic policies in the recipient countries [55], or because it's tied with the importing of products from the donor country over cheaper alternatives,[56] or because foreign aid is seen to be serving the interests of the donor more than the recipient.[57] Critics also argue that much of the foreign aid is stolen by corrupt governments and officials and that higher aid levels erode the quality of governance. Policy become much more oriented toward what will get more aid money than it does towards meeting the needs of the people.[58]

Supporters argue that these problems may be solved with better audit of how the aid is used.[59] Aid from non-governmental organizations may be more effective than governmental aid; this may be because it is better at reaching the poor and better controlled at the grassroots level.[60] The Borgen Project, an anti-poverty advocacy organization, estimates the annual cost of eliminating starvation and malnutrition globally at $19 billion a year.[61] As a point of comparison, the annual world military spending is over $1000 billion.[62]

Other approaches

Another method in helping to fight poverty is to have commodity exchanges that will supply necessary information about national and perhaps international markets to the poor who would then know what products and where it is sold will bring better profits. For example, in Ethiopia, remote farmers, who do not have this information, produce crops that may not bring the best profits. When they sell their procucts to a local trader, who then sells to another trader, and another, the cost of the food rises before it finally reaches the consumer in large cities. Economist, Gabre-Madhin proposes warehouses where farmers could have constant updates of the latest market prices, making the farmer think nationally, not locally. Each warehouse would have an independent neutral party that would test and grade the farmer's harvest, allowing traders in Addis Ababa, and potentially outside Ethiopia, to place bids on food, even if it is unseen. Thus, if the farmer gets five cents in one place he would get three times the price by selling it in another part of the country where there may be a drought.[63]

Some argue for a radical change of the economic system. There are several proposals for a fundamental restructuring of existing economic relations, and many of their supporters argue that their ideas would reduce or even eliminate poverty entirely if they were implemented. Such proposals have been put forward by both left-wing and right-wing groups: socialism, communism, anarchism, libertarianism, binary economics and participatory economics, among others.

Inequality can be reduced by progressive taxation, wealth tax, and inheritance tax.[citation needed]

In law, there has been a movement to seek to establish the absence of poverty as a human right.[citation needed]

The IMF and member countries have produced Poverty Reduction Strategy papers or PRSPs.[64]

In his book"The End of Poverty"[65], a prominent economist named Jeffrey Sachs laid out a plan to eradicate global poverty by the year 2025. Following his recommendations, international organizations such as the Global Solidarity Network are working to help eradicate poverty worldwide with intervention in the areas of housing, food, education, basic health, agricultural inputs, safe drinking water, transportation and communications.

The Poor People's Economic Human Rights Campaign is an organization in the United States working to secure freedom from poverty for all by organizing the poor themselves. The Campaign believes that a human rights framework, based on the value of inherent dignity and worth of all persons, offers the best means by which to organize for a political solution to poverty.

Religious poverty

- See also: Asceticism

Among some groups, in particular religious groups, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced in order to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation among Buddhists and Jains, whilst in Roman Catholicism it is one of the evangelical counsels, and taken as a vow among certain religious orders. The way poverty is understood among these orders takes a variety of forms. For example, the Franciscan orders have traditionally forgone all individual and corporate forms of ownership. However, while individual ownership of goods and wealth is forbidden for Benedictines, following the Rule of St. Benedict, the monastery itself may possess both goods and money, and through history some monasteries have become very rich indeed.

In this context of religious vows, poverty may be understood as a means of self-denial in order to place oneself at the service of others; Pope Honorius III wrote in 1217 that the Dominicans "lived a life of voluntary poverty, exposing themselves to innumerable dangers and sufferings, for the salvation of others". However, following Jesus' warning that riches can be like thorns that choke up the good seed of the word (Matthew 13:22), voluntary poverty is often understood by Christians as of benefit to the individual - a form of self-discipline by which one distances oneself from distractions from God.

Etymology

The words "poverty" and "poor" came from Latin pauper = "poor", which originally came from pau- and the root of pario, i.e. "giving birth to not much" and referred to unproductive farmland or livestock.

See also

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- Cycle of poverty

- Diseases of poverty

- Economic inequality

- Feminization of poverty

- Fuel poverty

- Global justice

- Hunger

- Income disparity

- International inequality

- International Development

- Literacy

- Minimum wage

- Pauperism

- Poverty threshold

- Poverty in the United States

- Poverty in the United Kingdom

- Social exclusion

- Subsidized housing

- Street children

- Ten Threats identified by the United Nations

- Welfare

- Working poor

- Make Poverty History

- The Hunger Site

- List of famines

- List of countries by fertility rate

Organizations and campaigns

- Global Poverty Minimization

- The George Foundation

- Abahlali baseMjondolo - South African Shack dwellers' organisation

- Global Call to Action Against Poverty (GCAP)

- The Make Poverty History campaign

- 17 October: UN International Day for the Eradication of Poverty(White Band Day 4)

- Center for Global Development

- Child Poverty Action Group

- Mississippi Teacher Corps

- Southern Poverty Law Center

- World Food Day

References

- ^ P Spicker, S Alvarez Leguizamon, D Gordon,(eds) 2007, Poverty: an international glossary.

- ^ Journal of Poverty

- ^ A Glossary for Social Epidemiology Nancy Krieger, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health

- ^ H Silver, 1994, social exclusion and social solidarity, in International Labour Review, 133 5-6

- ^ G Simmel, The poor, Social Problems 1965 13

- ^ P Townsend, 1979, Poverty in the UK, Penguin

- ^ {http://www1.worldbank.org/prem/poverty/voices/ Voices of the Poor}

- ^ Worldbank.org reference

- ^ Institute of Social Analysis

- ^ US Department of Human Services-FAQ Poverty Guidelines and Poverty

- ^ Rector, Robert E. and Johnson, Kirk A., Understanding Poverty in AmericaExecutive Summary, Heritage Foundation, January 15, 2004 No. 1713

- ^ Global Inequality Fades as the Global Economy Grows 2007 Index of Economic Freedom. Xavier Sala-i-Martin]

- ^ The Disturbing "Rise" of Global Income Inequality by Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2001

- ^ The Eight Losers of Globalization By Guy Pfeffermann.

- ^ World Development Volume 33, Issue 1 , January 2005, Pages 1-19, Why Are We Worried About Income? Nearly Everything that Matters is Converging

- ^ The World Health Report, World Health Organization (See annex table 2)

- ^ The Geography of Poverty and Wealth by Jeffrey D. Sachs, Andrew D. Mellinger, and John L. Gallup. From Scientific American magazine

- ^ Guns, Germs, and Steel Jared M. Diamond W. W. Norton & Company 1999

- ^ Hunger and Malnutrition paper by Jere R Behrman, Harold Alderman and John Hoddinott.

- ^ The long-run economic costs of AIDS: theory and an application to South Africa

- ^ The economic and social burden of malaria.

- ^ Poverty Issues Dominate WHO Regional Meeting

- ^ Ending Mass Poverty by Ian Vásquez

- ^ The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace by Morton Halperin, Joseph T. Siegle, Michael M. Weinstein, Joanne J. Myers

- ^ Global Competitiveness Report 2006, World Economic Forum, [1]. Infrastructure and Poverty Reduction: Cross-country Evidence Hossein Jalilian and John Weiss. 2004.

- ^ Global Competitiveness Report 2006, World Economic Forum, [2]

- ^ Global Competitiveness Report 2006, World Economic Forum, [3]

- ^ Transparency International FAQ

- ^ Birth rates 'must be curbed to win war on global poverty The Independent. 31 January 2007.

- ^ Demographic Transition by Keith Montgomery (Shows how population growth slows with industrialization.)

- ^ Western bankers and lawyers 'rob Africa of $150bn every year

- ^ The Paradox of Africa's Poverty By Tirfe Mammo. 1999. ISBN 1569020493. Gives credit to imperialism/colonialism as a cause as one of two major schools of thought.

- ^ Long-Run Development and the Legacy of Colonialism in Spanish America

- ^ Reflections on Colonial Legacy and Dependency in Indian Vocational Education and Training (VET): a societal and cultural perspective by Madhu Singh

- ^ The Mystery of Capital by Hernando de Soto (IMF)

- ^ The Communist Manifesto

- ^ Oxfam:Stop the dumping!

- ^ OECD Producer Support Estimate By Country

- ^ OECD Development Aid At a Glance By Region

- ^ Cultivating Poverty The Impact of US Cotton Subsidies on Africa

- ^ Six Reasons to Kill Farm Subsidies and Trade Barriers

- ^ ""U.S. Chamber of Commerce Fact Sheet "". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ See, e.g., "The Moral Doctrine of Poverty". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ http://www.usccb.org/cchd/epic/www/causesofpovertya.html

- ^ Vikram Patel. "Is Depression a Disease of Poverty?". Regional Health Forum WHO South-East Asia Region. 5 (1).

- ^ Urban and Slum Trends in the 21st Century By Eduardo Lopez Moreno and Rasna Warah

- ^ Lack of Toilets a Problem for the Poor, U.N. Says By CELIA W. DUGGER. New York Times. November 9, 2006

- ^ Dealing with Increased Risk of Natural Disasters: Challenges and Options PK Freeman, M Keen, M Mani - 2003

- ^ Social Protection and Risk Management at worldbank.org

- ^ PovertyNet worldbank.org

- ^ Poverty, Growth, and Inequality worldbank.org

- ^ The Doing Business database A member of the World Bank Group

- ^ WORLD BANK HAS GOOD NEWS ABOUT FUTURE By ANDREW CASSEL The Philadelphia Inquirer. Dec. 30, 2006

- ^ UN Millennium Project

- ^ Haiti's rice farmers and poultry growers have suffered greatly since trade barriers were lowered in 1994. By Jane Regan

- ^ Tied Aid Strangling Nations, Says U.N. by Thalif Deen

- ^ US and Foreign Aid, GlobalIssues.org

- ^ MYTH: More Foreign Aid Will End Global Poverty

- ^ MYTH: More Foreign Aid Will End Global Poverty

- ^ Does Foreign Aid Reduce Poverty? Empirical Evidence from Nongovernmental and Bilateral Aid

- ^ borgenproject.org

- ^ SIPRI Yearbook 2006

- ^ Market approach recasts often-hungry Ethiopia as potential bread basket

- ^ Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP)

- ^ The End of Poverty by JEFFREY D. SACHS for time.com

Further reading

- Atkinson, Anthony B. Poverty in Europe 1998

- Betson, David M., and Jennifer L. Warlick. "Alternative Historical Trends in Poverty." American Economic Review 88:348-51. 1998. in JSTOR

- Brady, David "Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty" Social Forces 81#3 2003, pp. 715-751 Online in Project Muse. Abstract: Reviews shortcomings of the official U.S. measure; examines several theoretical and methodological advances in poverty measurement. Argues that ideal measures of poverty should: (1) measure comparative historical variation effectively; (2) be relative rather than absolute; (3) conceptualize poverty as social exclusion; (4) assess the impact of taxes, transfers, and state benefits; and (5) integrate the depth of poverty and the inequality among the poor. Next, this article evaluates sociological studies published since 1990 for their consideration of these criteria. This article advocates for three alternative poverty indices: the interval measure, the ordinal measure, and the sum of ordinals measure. Finally, using the Luxembourg Income Study, it examines the empirical patterns with these three measures, across advanced capitalist democracies from 1967 to 1997. Estimates of these poverty indices are made available.

- Buhmann, Brigitte, Lee Rainwater, Guenther Schmaus, and Timothy M. Smeeding. 1988. "Equivalence Scales, Well-Being, Inequality, and Poverty: Sensitivity Estimates Across Ten Countries Using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database." Review of Income and Wealth 34:115-42.

- Cox, W. Michael, and Richard Alm. Myths of Rich and Poor 1999

- Danziger, Sheldon H., and Daniel H. Weinberg. "The Historical Record: Trends in Family Income, Inequality, and Poverty." Pp. 18-50 in Confronting Poverty: Prescriptions for Change, edited by Sheldon H. Danziger, Gary D. Sandefur, and Daniel. H. Weinberg. Russell Sage Foundation. 1994.

- Firebaugh, Glenn. "Empirics of World Income Inequality." American Journal of Sociology (2000) 104:1597-1630. in JSTOR

- Gans, Herbert, J., "The Uses of Poverty: The Poor Pay All", Social Policy, July/August 1971: pp. 20-24

- George, Abraham, Wharton Business School Publications - Why the Fight Against Poverty is Failing: A Contrarian View

- Gordon, David M. Theories of Poverty and Underemployment: Orthodox, Radical, and Dual Labor Market Perspectives. 1972.

- Haveman, Robert H. Poverty Policy and Poverty Research. University of Wisconsin Press 1987.

- John Iceland; Poverty in America: A Handbook University of California Press, 2003

- Alice O'Connor; "Poverty Research and Policy for the Post-Welfare Era" Annual Review of Sociology, 2000

- Osberg, Lars, and Kuan Xu. "International Comparisons of Poverty Intensity: Index Decomposition and Bootstrap Inference." The Journal of Human Resources 2000. 35:51-81.

- Paugam, Serge. "Poverty and Social Exclusion: A Sociological View." Pp. 41-62 in ;;The Future of European Welfare, edited by Martin Rhodes and Yves Meny 1998.

- Amartya Sen; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation Oxford University Press, 1982

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom (1999)

- Smeeding, Timothy M., Michael O'Higgins, and Lee Rainwater. Poverty, Inequality and Income Distribution in Comparative Perspective. Urban Institute Press 1990.

- Triest, Robert K. "Has Poverty Gotten Worse?" Journal of Economic Perspectives 1998. 12:97-114.

External links

- The Crime of Poverty by Henry George

- The George Foundation

- The Borgen Project

- Rural Poverty Portal Powered by IFAD

- Global Distribution of Poverty Global poverty datasets and map collection

- Why Poor Countries are Poor

- The End of Poverty - an interview with Jeff Sachs - Yale Economic Review

- Fighting Hunger and poverty in Ethiopia (Peter Middlebrook)

- Poverty in the United States, by Isabel V. Sawhill. Concise encyclopedia of economics on Econlib

- Social Solutions to Poverty: America's Struggle to Build a Just Society, Scott Myers-Lipton, (2006).

- Catholic Encyclopedia "Poverty and Pauperism"

- Poverty on the Development Gateway portal

- Poverty on the World Bank portal

- Template:Dmoz

- Unicef State of the World's Children report 2006 on different kinds of child poverty.

- UNDP Poverty

- UN DESA - Poverty Eradication

- A CICRED book for download on poverty and human fertility

- Community Action Partnership [5] America's Poverty Fighting Network

- Malaria Disease of Poverty, Andrew Speilman, Harvard University Freeview video by the Vega Science Trust.

- Education Is The Key To Reducing Poverty, Omedia

- Poverty related Statistics by UN Millennium Project.

- Global Poverty as a Citizenship Issue

- Poverty Slideshow

- BasicNeeds International development charity working to alleviate the poverty experienced by mentally ill people.

- Causes of Poverty, GlobalIssues.org

- End Poverty Campaign

Organizations and campaigns

- The Borgen Project

- Compassion International

- End Poverty Campaign to end extreme global poverty and hunger by 2012

- Catholic Charities USA Campaign to Reduce Poverty in America

- Nourish International

- Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC)

- People-Centered Economic Development

- The Anti-Poverty Campaign

- Make Poverty History