Easter egg: Difference between revisions

John Darrow (talk | contribs) m Undid revision 281284895 by 70.46.34.194 (talk) revert vandalism |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

The egg is seen as symbolic of the grave and life renewed or resurrected by breaking out of it. The red supposedly symbolizes the blood of Christ redeeming the world and human redemption through the blood shed in the sacrifice of the [[Crucifixion of Jesus|crucifixion]]. The egg itself is a symbol of [[Resurrection of Jesus|resurrection]]: while being dormant it contains a new life sealed within it. |

The egg is seen as symbolic of the grave and life renewed or resurrected by breaking out of it. The red supposedly symbolizes the blood of Christ redeeming the world and human redemption through the blood shed in the sacrifice of the [[Crucifixion of Jesus|crucifixion]]. The egg itself is a symbol of [[Resurrection of Jesus|resurrection]]: while being dormant it contains a new life sealed within it. |

||

For Orthodox Christians, the Easter egg is much more than a celebration of the ending of the fast, it is a declaration of the [[Resurrection of Jesus]]. Traditionally, Orthodox Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the [[blood of Christ]], shed on the Cross, and the hard shell of the egg |

For Orthodox Christians, the Easter egg is much more than a celebration of the ending of the fast, it is a declaration of the [[Resurrection of Jesus]]. Traditionally, Orthodox Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the [[blood of Christ]], shed on the Cross, and the hard shell of the egg symbolizedbl the sealed [[Holy Sepulchre|Tomb of Christ]]—the cracking of which symbolized his resurrection from the dead. BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH |

||

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are [[blessing|blessed]] by the priest at the end of the [[Paschal Vigil]], and distributed to the faithful. Each household also brings an Easter basket to church, filled not only with Easter eggs but also with other Paschal foods such as [[paskha (meal)|paskha]], [[kulich]] or [[Easter bread]]s, and these are blessed by the priest as well. |

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are [[blessing|blessed]] by the priest at the end of the [[Paschal Vigil]], and distributed to the faithful. Each household also brings an Easter basket to church, filled not only with Easter eggs but also with other Paschal foods such as [[paskha (meal)|paskha]], [[kulich]] or [[Easter bread]]s, and these are blessed by the priest as well. |

||

Revision as of 01:40, 3 April 2009

Easter eggs are specially decorated eggs given to celebrate the Easter holiday or springtime.

The egg was a symbol of the rebirth of the earth in Pagan celebrations of spring and was adopted by early Christians as a symbol of the rebirth.[1]

The oldest tradition is to use dyed or painted chicken eggs, but a modern custom is to substitute chocolate eggs, or plastic eggs filled with confectionery such as jellybeans. These eggs are often hidden, allegedly by the Easter Bunny, for good children to find on Easter morning. Otherwise, they are generally put in a basket filled with real or artificial straw to resemble a bird's nest.

Origin and folklore

The egg is widely used as a symbol of the start of new life, just as new life emerges from an egg when the chick hatches out.[citation needed]

The ancient Persians painted eggs for Nowrooz, their New Year celebration, which falls on the Spring equinox. The Nawrooz tradition has existed for at least 2,500 years. The decorated eggs are one of the core items to be placed on the Haft Seen, the Persian New Year display. The sculptures on the walls of Persepolis show people carrying eggs for Nowrooz to the king.

At the Jewish Passover Seder, a hard-boiled egg dipped in salt water symbolizes the Passover sacrifice offered at the Temple in Jerusalem.

The pre-Christian Saxons had a spring goddess called Eostre, whose feast was held on the Vernal Equinox, around 21 March. Her animal was the spring hare. Some believe that Ēostre was associated with eggs and hares,[3] and the rebirth of the land in spring was symbolised by the egg. Ēostre is known from the writings of Bede Venerabilis, a seventh-century Benedictine monk. Bede describes the pagan worship of Ēostre among the Anglo-Saxons as having died out before he wrote about it. Bede's De temporum ratione attributes her name to the festival, but does not mention eggs at all.[4]

Other theories such as Jakob Grimm’s in the 18th Century believe in a pagan connection to Easter eggs via a putatively Germanic goddess called Ostara.

The Western name for the festival of Easter derives from the Germanic word Eostre. It is only in Germanic languages that a derivation of Eostre marks the holiday. Most European languages use a term derived from the Hebrew pasch meaning Passover. In Spanish, for example, it is Pascua; in French, Pâques; in Dutch, Pasen; in Greek, Russian and the languages of most Eastern Orthodox countries: Pascha. Some languages use a term meaning Resurrection, such as Serbian Uskrs.

Pope Gregory the Great ordered his missionaries to use old religious sites and festivals, and absorb them into Christian rituals where possible. The Christian celebration of the Resurrection of Christ was ideally suited to be merged with the Pagan feast of Eostre, and many of the traditions were adopted into the Christian festivities.[5] There are also good grounds for the association between hares (later termed Easter bunnies) and eggs, through folklore confusion between hares' forms (where they raise their young) and plovers' nests.[6]

Christian symbols and practice

The egg is seen as symbolic of the grave and life renewed or resurrected by breaking out of it. The red supposedly symbolizes the blood of Christ redeeming the world and human redemption through the blood shed in the sacrifice of the crucifixion. The egg itself is a symbol of resurrection: while being dormant it contains a new life sealed within it.

For Orthodox Christians, the Easter egg is much more than a celebration of the ending of the fast, it is a declaration of the Resurrection of Jesus. Traditionally, Orthodox Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the blood of Christ, shed on the Cross, and the hard shell of the egg symbolizedbl the sealed Tomb of Christ—the cracking of which symbolized his resurrection from the dead. BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are blessed by the priest at the end of the Paschal Vigil, and distributed to the faithful. Each household also brings an Easter basket to church, filled not only with Easter eggs but also with other Paschal foods such as paskha, kulich or Easter breads, and these are blessed by the priest as well.

During Paschaltide, in some traditions the Paschal greeting with the Easter egg is even extended to the deceased. On either the second Monday or Tuesday of Pascha, after a memorial service people bring blessed eggs to the cemetery and bring the joyous paschal greeting, "Christ has risen", to their beloved departed (see Radonitza).

Pious legends

While the origin of easter eggs can be explained in the symbolic terms described above, a pious legend among followers of Eastern Christianity says that Mary Magdalene was bringing cooked eggs to share with the other women at the tomb of Jesus, and the eggs in her basket miraculously turned brilliant red when she saw the risen Christ.[7]

A different, but not necessarily conflicting, legend concerns Mary Magdalene's efforts to spread the Gospel. According to this tradition, after the Ascension of Jesus, Mary went to the Emperor of Rome and greeted him with “Christ has risen,” whereupon he pointed to an egg on his table and stated, “Christ has no more risen than that egg is red.” After making this statement it is said the egg immediately turned blood red.

Decorating techniques

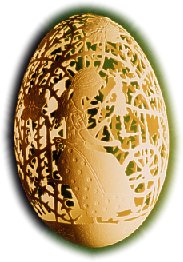

Easter eggs are a widely popular symbol of new life in Russia, Romania, Ukraine, Poland and other Slavic countries' folk traditions. A batik (wax resist) process is used to create intricate, brilliantly-colored eggs., the best-known of which is the Ukrainian pysanka. The celebrated Fabergé workshops created exquisite jewelled Easter eggs for the Russian Imperial Court. Most of these creations themselves contained hidden surprises such as clock-work birds, or miniature ships. A 27-foot (9 m) sculpture of a pysanka stands in Vegreville, Alberta.

There are many other decorating techniques and numerous traditions of giving them as a token of friendship, love or good wishes. A tradition exists in some parts of the United Kingdom (such as Scotland and North East England) of rolling painted eggs down steep hills on Easter Sunday. In the U.S., such an Easter egg roll (unrelated to an eggroll) is often done on flat ground, pushed along with a spoon; the Easter Egg Roll has become a much-loved annual event on the White House lawn. An Easter egg hunt is a common festive activity, where eggs are hidden outdoors (or indoors if in bad weather) for children to run around and find. This may also be a contest to see who can collect the most eggs.

When boiling hard-cooked eggs for Easter, a popular tan colour can be achieved by boiling the eggs with onion skins. A greater variety of colour was often provided by tying on the onion skin with different coloured woollen yarn. In the North of England these are called pace-eggs or paste-eggs. They were usually eaten after an egg-jarping (egg-tapping) competition.

Easter egg traditions

Egg hunt is a game during which decorated eggs, real hard-boiled ones or artificial, filled with or made of chocolate candies, of various sizes, are hidden for children to find, both indoors and outdoors.[8] [9]

When the hunt is over, prizes may be given for the largest number of eggs collected, for the largest of the smallest egg,.[9]

Real eggs may further be used in egg tapping contests.

In the North of England, at Eastertime, a traditional game is played where hard boiled pace eggs are distributed and each player hits the other player's egg with their own. This is known as "egg tapping", "egg dumping" or "egg jarping". The winner is the holder of the last intact egg. The losers get to eat their eggs. The annual egg jarping world championship is held every year over Easter in Peterlee Cricket Club. It is also practiced in Bulgaria, Hungary, Croatia, Lebanon, Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, and other countries. They call it tucanje. In parts of Austria, Bavaria and German-speaking Switzerland it is called Ostereiertitschen or Eierpecken. In South Louisiana this practice is called Pocking Eggs[10][11] and is slightly different. The Cajuns hold that the winner eats the eggs of the losers in each round.

Egg rolling is also a traditional Easter egg game played with eggs at Easter. In England, Germany, and other countries children traditionally rolled eggs down hillsides at Easter.[12]

This tradition, was taken to the New World by European settlers [12][13]

Different nations have different versions of the game.

Egg dance is a traditional Easter game in which eggs are laid on the ground or floor and the goal is to dance among them without damaging any eggs[14] which originated in Germany. In the UK the dance is called the hop-egg.

The Pace Egg plays are traditional village plays, with a rebirth theme. The drama takes the form of a combat between the hero and villain, in which the hero is killed and brought to life, The plays take place in England during Easter.

As food

The Easter egg tradition may also have merged into the celebration of the end of the privations of Lent in the West. Historically, it was traditional to use up all of the household's eggs before Lent began. Eggs were originally forbidden during Lent as well as on other traditional fast days in Western Christianity (this tradition still continues among the Eastern Christian Churches). Likewise, in Eastern Christianity, both meat and dairy are prohibited during the Lenten fast, and eggs are seen as "dairy" (a foodstuff that could be taken from an animal without shedding its blood). This established the tradition of Pancake Day being celebrated on Shrove Tuesday. This day, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday Lent begins is also known as Mardi Gras, a French phrase which translates as "Fat Tuesday" to mark the last consumption of eggs and dairy before Lent begins.

In the Orthodox Church, Great Lent begins on Clean Monday, rather than Wednesday, so the household's dairy products would be used up in the preceding week, called Cheesefare Week. During Lent, since chickens would not stop producing eggs during this time, a larger than usual store might be available at the end of the fast if the eggs had not been allowed to hatch. The surplus, if any, had to be eaten quickly to prevent spoiling. Then, with the coming of Easter, Pascha the eating of eggs resumes.

One would have been forced to hard boil the eggs that the chickens produced so as not to waste food, and for this reason the Spanish dish hornazo (traditionally eaten on and around Easter) contains hard-boiled eggs as a primary ingredient. In Hungary, easter eggs are used sliced in potato casseroles around Easter.

Easter eggs for the visually-impaired

Beeping Easter eggs are Easter eggs that emit various clicks and noises so that the visually-impaired children can easily hunt for Easter eggs.

Some beeping Easter eggs make a single, high-pitched sound some other beeping Easter eggs play a melody.[15]

Easter eggs from different countries

-

Easter eggs from Croatia

-

Drapanka from Poland

-

Drapanka from Poland

-

Pace-eggs.

-

American Easter eggs from Washington

-

Scandinavian Easter eggs

-

Candle dripped Easter eggs from South Bend, IN, USA

-

Foil-wrapped chocolate Easter eggs.

See also

- Egg decorating in Slavic culture

- Fabergé eggs

- Festum Ovorum

- Paas

- Pisanica (Croatian)

- Pisanka (Polish)

- Pysanka (Ukrainian)

- Sham El Nessim

- Święconka

References

- ^ Warwickshire County Council: The history of the Easter egg Retrieved on 2008-03-17

- ^ http://www.mieks.com/Faberge2/1885-Hen-Egg.htm Article on the first Hen egg

- ^ Channel 4 - Time Team

- ^ Beda Venerabilis

- ^ england-in-particular: Easter Retrieved on 2008-03-14

- ^ BBC - h2g2 - The Easter Bunny

- ^ Traditions of Great Lent and Holy Week[1] Melkite Greek Catholic Eparchy of Newton

- ^ Warwickshire County Council: The history of the Easter egg Retrieved on 2008-03-17

- ^ a b "An April Birthday Party", by Margaret Remington, The Puritan, April-September 1900.

- ^ "Pocking eggs or la toquette". Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "If Your Eggs Are Cracked, Please Step Down: Easter Egg Knocking in Marksville". Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ a b see http://inventors.about.com/od/estartinventions/a/easter_2.htm Retrieved on 2008-03-15

- ^ Easter Eggs: their origins, tradition and symbolism Retrieved on 2008-03-15

- ^ Venetia Newall (1971) An Egg at Easter: A Folklore Study, p. 344

- ^ Tillery, Carolyn (2008-03-15). "Annual Dallas Easter egg hunt for blind children scheduled for Thursday". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 2008-03-27.