Dragon Quest (video game): Difference between revisions

m →Related media: copyediting |

Standardized and more consistently formatted citations. |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

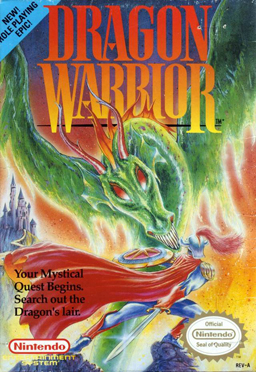

|caption=Box art |

|caption=Box art |

||

|developer=[[Chunsoft]] |

|developer=[[Chunsoft]] |

||

|publisher={{ |

|publisher={{Video game release|JP=[[Enix]]|NA=[[Nintendo]]}} |

||

|designer=[[Yūji Horii]] |

|designer=[[Yūji Horii]] |

||

|programmer=[[Koichi Nakamura]] |

|programmer=[[Koichi Nakamura]] |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

{{see also|Gameplay of Dragon Quest}} |

{{see also|Gameplay of Dragon Quest}} |

||

''Dragon Warrior'' is a role-playing video game which uses mechanics that, years after its release, have been described as simplistic to the point of being Spartan and archaic.<ref name=kurt>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3520/the_history_of_dragon_quest.php?print=1|title=The History of Dragon Quest|first=Kurt|last=Kalata|publisher=[[Gamasutra]]|accessdate=March 26, 2011}}</ref><ref name=Johnson>{{cite web | url=http://www.rpgamer.com/games/dq/dq1/reviews/dq1strev1.html |title=Dragon Quest – Review | |

''Dragon Warrior'' is a role-playing video game which uses mechanics that, years after its release, have been described as simplistic to the point of being Spartan and archaic.<ref name=kurt>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3520/the_history_of_dragon_quest.php?print=1|title=The History of Dragon Quest|first=Kurt|last=Kalata|publisher=[[Gamasutra]] |date=February 4, 2008 |accessdate=March 26, 2011}}</ref><ref name=Johnson>{{cite web | url=http://www.rpgamer.com/games/dq/dq1/reviews/dq1strev1.html |title=Dragon Quest – Review |accessdate=March 26, 2011 |last=Johnson |first=Bill |publisher=[[RPGamer]]}}</ref> In the game, players control the descendent of [[Erdrick]] as he sets out to defeat the Dragonlord.<ref name=manual56>{{cite manual |title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=[[Nintendo of America]] |location=[[Redmond, WA]] |year=1989 |id=NES-DQ-USA |pages=5–6}}</ref> Before starting the game, players are presented with a menu screen; depending on the circumstances, players can do the following: begin a new game known as a quest; continue a previous quest;{{#tag:ref|In the Famicom version, players must enter a [[password (video games)|password]] to continue a quest. In the NES version, the quest is [[save game|saved]] in the cartridge's battery-backup known in the game as an "Adventure Log" in the "Imperial Scrolls of Honor".)<ref name=kurt/>|group=note}} or change the speed in which messages appear on the screen. The NES version also has options to delete a quest or copy one to another slot on the cartridge. If players choose a new quest, they can give their hero any name they wish that is up to eight letters in length.<ref name="Manual78">{{cite manual |section=Welcome to the Realm of "Dragon Warrior"|title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-DQ-USA |year=1989 |pages=7–8}}</ref> Players can name the Hero within the limits of the naming system (eight letters in the North American NES version,<ref name=DW1NES>{{cite video game|title=Dragon Warrior|developer=Chunsoft|publisher=Nintendo|date=1989|platform=Nintendo Entertainment System}}</ref> four [[kana]] characters in the Japanese [[Famicom]] version).<ref name=DQ1FAM>{{cite video game|title=Dragon Quest|developer=Chunsoft|publisher=Enix|date=1986|platform=Famicom}}</ref> The Hero's name has an effect on his initial ability scores and their statistical growth over the course of the game.{{#tag:ref|The game uses a formula based on the letters (in English) or [[kana]] (in Japanese) used in the character's name to determine how the player's stat growth is determined. Each stat falls in one of two categories, one with faster growth than the other, and the formula which uses the entire name determines which path each of the stats use.<ref name="Guide 6/105">{{cite book|title=Dragon Warrior I and II Official Strategy Guide |year=2000 |publisher=[[Prima Publishing]] |location=[[New York, NY]] |isbn=978-0-7615-3157-9 |pages=6, 105}}</ref>|group=note}} |

||

''Dragon Warrior'' gives players a "clear objective" from the start by using a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve it.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History">{{cite web|url=http://dqnine.com/wii/iwata/|title=Dragon Quest: Sentinel of the Starry Skies|work=Iwata Asks|publisher=Square-Enix|at=The History of Dragon Quest|accessdate=December 5, 2010}}</ref> Players begin the game in King Lorik's chamber in Tantegel Castle, where they receive information about the Dragonlord and the stolen Balls of Light.{{#tag:ref|The Balls of Light are also known by the singular, Ball of Light.<ref name=manual56/>|group=note|name=Ball}} After receiving some items and gold, the hero then sets out on his quest. Much of ''Dragon Warrior'' consists of talking to [[non-player character|townspeople]] and gathering information from them, which allows players to discover additional places, events, and secrets. Players are advised to take notes on the information for future reference. In addition to information, towns contain the following: shops which sell improved weapons and armor, general stores which sell other goods, inns which recover players' health and magic, and places which sell keys; players can sell items to any shop that sells weapons, armor or general goods store at half their cost. The status displays contain additional information and statistics for the hero. The status window, which is displayed whenever the player stops moving, contains the hero's current [[experience level]] (LV) and the current amount of [[hit point]]s (HP), [[magic point]]s (MP), gold (G), and [[experience point]]s (E).<ref name=DW1NES/><ref name="manual20212932">{{cite |

''Dragon Warrior'' gives players a "clear objective" from the start by using a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve it.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History">{{cite web|url=http://dqnine.com/wii/iwata/|title=Dragon Quest: Sentinel of the Starry Skies|work=Iwata Asks|publisher=Square-Enix|at=The History of Dragon Quest|accessdate=December 5, 2010}}</ref> Players begin the game in King Lorik's chamber in Tantegel Castle, where they receive information about the Dragonlord and the stolen Balls of Light.{{#tag:ref|The Balls of Light are also known by the singular, Ball of Light.<ref name=manual56/>|group=note|name=Ball}} After receiving some items and gold, the hero then sets out on his quest. Much of ''Dragon Warrior'' consists of talking to [[non-player character|townspeople]] and gathering information from them, which allows players to discover additional places, events, and secrets. Players are advised to take notes on the information for future reference. In addition to information, towns contain the following: shops which sell improved weapons and armor, general stores which sell other goods, inns which recover players' health and magic, and places which sell keys; players can sell items to any shop that sells weapons, armor or general goods store at half their cost. The status displays contain additional information and statistics for the hero. The status window, which is displayed whenever the player stops moving, contains the hero's current [[experience level]] (LV) and the current amount of [[hit point]]s (HP), [[magic point]]s (MP), gold (G), and [[experience point]]s (E).<ref name=DW1NES/><ref name="manual20212932">{{cite manual |section=How to Start Off on the Right Foot (What you must do at the beginning of the game) |title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-DQ-USA |year=1989 |pages=20–21, 29–32}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Dragon quest battle 2.png|thumb|left|Battling a [[Slime (Dragon Quest)|Slime]] in ''Dragon Warrior'' for the [[Nintendo Entertainment System|NES]]]] |

[[Image:Dragon quest battle 2.png|thumb|left|Battling a [[Slime (Dragon Quest)|Slime]] in ''Dragon Warrior'' for the [[Nintendo Entertainment System|NES]]]] |

||

To progress to future areas in the game, players need to build additional strength by accumulating experience points and gold from defeating enemies outside of towns in the [[overworld]] and in dungeons.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2">{{cite web |url=http://gameboy.ign.com/articles/164/164493p1.html |title=Dragon Warrior I & II Review |first=Mark |last=Nix |publisher=[[IGN]] |accessdate=October 6, 2009}}</ref> Enemies appear [[random encounter|randomly]]; as with the other games in the ''Dragon Quest'' series, battles are [[turn-based]] and one-on-one, and are fought from a first-person perspective, while the hero remains offscreen.<ref name=kurt/> During battles, the player has four commands: "fight", "run", "spell", or "item"; the objective is to attack the enemy and reduce the enemy's hit point total to zero, thus defeating it. The "fight" command causes the hero to attack the enemy with a weapon (or with bare fists if no weapon is available), attempting to damage the enemy. The "run" command causes the hero to attempt to escape from the battle, which is recommended if the hero's HP is low. The "spell" command casts a spell that is directed at the hero (such as healing spells) or at the enemy for damage. The "item" command is used to utilize herbs during battle, which helps replenish the hero's HP.<ref name="Manual1314">{{cite |

To progress to future areas in the game, players need to build additional strength by accumulating experience points and gold from defeating enemies outside of towns in the [[overworld]] and in dungeons.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2">{{cite web |url=http://gameboy.ign.com/articles/164/164493p1.html |title=Dragon Warrior I & II Review |first=Mark |last=Nix |publisher=[[IGN]] |date=October 4, 2000 |accessdate=October 6, 2009}}</ref> Enemies appear [[random encounter|randomly]]; as with the other games in the ''Dragon Quest'' series, battles are [[turn-based]] and one-on-one, and are fought from a first-person perspective, while the hero remains offscreen.<ref name=kurt/> During battles, the player has four commands: "fight", "run", "spell", or "item"; the objective is to attack the enemy and reduce the enemy's hit point total to zero, thus defeating it. The "fight" command causes the hero to attack the enemy with a weapon (or with bare fists if no weapon is available), attempting to damage the enemy. The "run" command causes the hero to attempt to escape from the battle, which is recommended if the hero's HP is low. The "spell" command casts a spell that is directed at the hero (such as healing spells) or at the enemy for damage. The "item" command is used to utilize herbs during battle, which helps replenish the hero's HP.<ref name="Manual1314">{{cite manual |section=Entering Commands during Fighting Mode/More About Your Character | title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-DQ-USA |year=1989 |pages=13–14}}</ref> |

||

During battles, the hero loses HP as he sustains damage, and the display turns red when his HP is too low; if the hero's HP goes down to zero, he dies and is then taken back to King Lorik, where he is resurrected and loses half his gold as punishment.<ref name="manual20212932"/>{{#tag:ref|The GBC includes a bank where the player can store some of their money in case they die.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/>|group=note}} If the hero succeeds in defeating an enemy, he gains experience points and gold; if enough experience points are gained, his experience level will increase, giving him the ability to use magic spells as well as greater strength, agility, and speed.<ref name="NP8">{{cite journal |title=''Dragon Warrior'' |magazine=[[Nintendo Power]] |publisher=[[ |

During battles, the hero loses HP as he sustains damage, and the display turns red when his HP is too low; if the hero's HP goes down to zero, he dies and is then taken back to King Lorik, where he is resurrected and loses half his gold as punishment.<ref name="manual20212932"/>{{#tag:ref|The GBC includes a bank where the player can store some of their money in case they die.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/>|group=note}} If the hero succeeds in defeating an enemy, he gains experience points and gold; if enough experience points are gained, his experience level will increase, giving him the ability to use magic spells as well as greater strength, agility, and speed.<ref name="NP8">{{cite journal |title=''Dragon Warrior'' |magazine=[[Nintendo Power]] |publisher=[[Tokuma Shoten]] |location=Redmond, WA |issue=8 |date=September/October 1989 |pages=20–27 |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582}}</ref> Every time a spell is used, the hero's MP decreases; the amount of MP consumed depends on the type of spell cast. Both HP and MP can be restored by resting at an inn, additionally MP can be restores with an NPC in Tantegel Castle.<ref name="Manual1314" /> As the hero earns more gold, he can use it to purchase better weapons, armor, and items.<ref>{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior I and II Official Strategy Guide |publisher=Prima Publishing |location=New York, NY |isbn=978-0-7615-3157-9 |year=2000 |pages=3, 5}}</ref> However, the player has limited inventory space to hold items, meaning that the player must manage the collection of items conservatively.<ref name=kurt/> At any point in the NES version, the player can return to King Lorik in Tantegel Castle to save their quest (known in the game as "recording their deeds on the 'Imperial Scrolls of Honor'");<ref name="NP8" /><ref>{{cite manual |section=Visit the King And Have Your Deeds Recorded on the Imperial Scrolls of Honor (to save your game) |title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-DQ-USA |year=1989 |page=28}}</ref> since the Famicom version does not have a battery backup, visiting the king gives players a password to use for a later time.<ref name="kurt"/> |

||

Players use the control pad to move the player in any direction and to move the flashing cursor in menu displays. Additional buttons are also available to confirm and cancel commands. In the NES version of ''Dragon Warrior'', players must use menu commands to talk to people check their status, search beneath them, use items, take treasure chests, open doors, and go up or down stairs.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/><ref>{{cite |

Players use the control pad to move the player in any direction and to move the flashing cursor in menu displays. Additional buttons are also available to confirm and cancel commands. In the NES version of ''Dragon Warrior'', players must use menu commands to talk to people check their status, search beneath them, use items, take treasure chests, open doors, and go up or down stairs.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/><ref>{{cite manual |section=How to use the Controller and Displays | title=Dragon Warrior: Instruction Booklet |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-DQ-USA |year=1989 |pages=9–12}}</ref> However, in some of the later remakes, some of these commands were assigned to buttons, and using the stairs became automatic.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/><ref name=DW1&2GBC>{{cite video game|title=Dragon Warrior I & II|developer=[[TOSE]]|publisher=Enix|date=2000|platform=Game Boy Color}}</ref> Also, in the Famicom version, since all characters face forward, players must choose the command as well as choose a direction to execute commands such as talking to other non player characters.<ref name=kurt/> |

||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

===Backstory=== |

===Backstory=== |

||

''Dragon Warrior''{{'}}s plot is a simplistic medieval "rescue the princess and slay the dragon" story.<ref name=Johnson/><ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> The story's background goes back many generations, where the kingdom of Alefgard was shrouded in permanent darkness. Then, the brave warrior Erdrick defeated an evil creature to restore light to the land. In his possession was the Balls of Light,<ref group=note name=Ball/> which he used to drive away the enemies who threatened the kingdom. He then handed the balls of light to King Lorik, and Alefgard remained peaceful for a long time.<ref name=manual56/> The Balls of Light kept winters short in Alefgard and helped maintain peace and proposerity in Alefgard.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook">{{cite manual |title=Dragon Warrior Explorer's Handbook |publisher=Nintendo |location=Redmond, WA |year=1989 |pages=58–60}}</ref> |

''Dragon Warrior''{{'}}s plot is a simplistic medieval "rescue the princess and slay the dragon" story.<ref name=Johnson/><ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> The story's background goes back many generations, where the kingdom of Alefgard was shrouded in permanent darkness. Then, the brave warrior Erdrick defeated an evil creature to restore light to the land. In his possession was the Balls of Light,<ref group=note name=Ball/> which he used to drive away the enemies who threatened the kingdom. He then handed the balls of light to King Lorik, and Alefgard remained peaceful for a long time.<ref name=manual56/> The Balls of Light kept winters short in Alefgard and helped maintain peace and proposerity in Alefgard.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook">{{cite manual |section=''Dragon Warrior'' – The Saga |title=Dragon Warrior Explorer's Handbook |publisher=Nintendo |location=Redmond, WA |year=1989 |pages=58–60}}</ref> |

||

However, there was one who shunned Ball of Light's radiance and secluded himself in a mountain cave. One day, while exploring the cave's extensive network of tunnels, this man encountered a sleeping dragon who awoke upon his entrance; he feared that the dragon would incinerate him with its fiery breath. Instead, the dragon knelt before him and obeyed his commands. This man, who is later discovered to be a dragon,<ref name="np6_52">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1989| |

However, there was one who shunned Ball of Light's radiance and secluded himself in a mountain cave. One day, while exploring the cave's extensive network of tunnels, this man encountered a sleeping dragon who awoke upon his entrance; he feared that the dragon would incinerate him with its fiery breath. Instead, the dragon knelt before him and obeyed his commands. This man, who is later discovered to be a dragon,<ref name="np6_52">{{Cite journal |title=Previews – ''Dragon Warrior''|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1989|issue=6|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |pages=52–53 |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582}}</ref> became known as the Dragonlord,<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> whose soul became corrupted by learning magic.<ref name="np6_52"/> Then, one day, the Dragonlord attacked Tantegel Castle and the nearby town of Breconnary with his fleet of dragons, setting the town on fire. Riding a large red dragon, the Dragonlord descended upon the highest tower of Tantegel Castle and stole the Balls of Light. Soon, monsters began to appear throughout the entire land, destroying everything in their path;<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> much of the land became poisonous marshes, and some towns and villages were completely destroyed.<ref name=manual56/> |

||

The following day, the battle-ridden Erdrick,<ref group=note>Erdrick is known as Loto in the GBC remake.</ref> arrived at Tantegel Castle to speak with King Lorik and offered his help to defeat the Dragonlord. After searching the land for clues to the Dragonlord's whereabouts, Erdrick found that he resides on an island that could only be accessed via a magical bridge generated by a "Rainbow Drop". After arriving on the island, Erdrick was never heard from again.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> Many years later, during King Lorik XVI's reign,<ref name=manual56/> the Dragonlord attacked the kingdom again and captured Princess Gwaelin in the process.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> Many tried to rescue the princess and recover the Balls of Light from the Dragonlord's castle Charlock, but none succeeded. Then, the prophet Mahetta made the following prediction: "One day, a descendant of the valiant Erdrick shall come forth to defeat the Dragonlord."<ref name=manual56/> However, by the time he arrives, many had forgotten the story of Erdrick, and almost all those who did remember it considered it a myth; few believed in his prophecy. King Lorik then started to mourn the decline of his kingdom.<ref name=DWSG4>{{cite book | |

The following day, the battle-ridden Erdrick,<ref group=note>Erdrick is known as Loto in the GBC remake.</ref> arrived at Tantegel Castle to speak with King Lorik and offered his help to defeat the Dragonlord. After searching the land for clues to the Dragonlord's whereabouts, Erdrick found that he resides on an island that could only be accessed via a magical bridge generated by a "Rainbow Drop". After arriving on the island, Erdrick was never heard from again.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> Many years later, during King Lorik XVI's reign,<ref name=manual56/> the Dragonlord attacked the kingdom again and captured Princess Gwaelin in the process.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> Many tried to rescue the princess and recover the Balls of Light from the Dragonlord's castle Charlock, but none succeeded. Then, the prophet Mahetta made the following prediction: "One day, a descendant of the valiant Erdrick shall come forth to defeat the Dragonlord."<ref name=manual56/> However, by the time he arrives, many had forgotten the story of Erdrick, and almost all those who did remember it considered it a myth; few believed in his prophecy. King Lorik then started to mourn the decline of his kingdom.<ref name=DWSG4>{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior: Strategy Guide |last=Pelland |first=Scott |publisher=Nintendo of America |year=1989 |oclc=30018721 |location=Redmond, WA | page=4}}</ref> |

||

===Main story=== |

===Main story=== |

||

The game begins when a stranger, the role whom the player assumes, appears at Tantegel Castle. He learns about the princess' capture and that she is being held by a dragon in a distant cave; other [[non-player character|character]]s task this hero to rescue her.<ref>{{cite manual |title=Dragon Warrior Explorer's Handbook |page=7}}</ref> Determined to rescue the princess and defeat the Dragonlord, he discovers an ancient tablet in a cave in a desert; carved on the tablet contained a message from Erdrick, outlining what the hero needs to do to follow in Erdrick's footsteps and defeat the Dragonlord.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> He eventually rescues Princess Gwaelin, but he realizes that, in order to restore Alefgard, he must defeat the Dragonlord, who now resides in Charlock Castle. After the Hero has collected the relics, he creates a bridge to reach the Charlock and, after fighting his way through the castle, the hero confronts the Dragonlord. At this point, the hero is given the choice to side with the Dragonlord or fight him. If players choose the former, the game ends, the Hero is put to sleep and the game freezes;<ref name=kurt/> however, in the [[Game Boy]] remake, the Hero wakes up from a bad dream. If players refuse, the Hero then fights the Dragonlord.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /><ref name="Guide 30">{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior I and II Official Strategy Guide |page=30}}</ref> |

The game begins when a stranger, the role whom the player assumes, appears at Tantegel Castle. He learns about the princess' capture and that she is being held by a dragon in a distant cave; other [[non-player character|character]]s task this hero to rescue her.<ref>{{cite manual |section=Tantegel Castle – Before You Leave the Castle |title=Dragon Warrior Explorer's Handbook |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |year=1989 |id=NES-DQA-USA |page=7}}</ref> Determined to rescue the princess and defeat the Dragonlord, he discovers an ancient tablet in a cave in a desert; carved on the tablet contained a message from Erdrick, outlining what the hero needs to do to follow in Erdrick's footsteps and defeat the Dragonlord.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /> He eventually rescues Princess Gwaelin, but he realizes that, in order to restore Alefgard, he must defeat the Dragonlord, who now resides in Charlock Castle. After the Hero has collected the relics, he creates a bridge to reach the Charlock and, after fighting his way through the castle, the hero confronts the Dragonlord. At this point, the hero is given the choice to side with the Dragonlord or fight him. If players choose the former, the game ends, the Hero is put to sleep and the game freezes;<ref name=kurt/> however, in the [[Game Boy]] remake, the Hero wakes up from a bad dream. If players refuse, the Hero then fights the Dragonlord.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /><ref name="Guide 30">{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior I and II Official Strategy Guide |publisher=Prima Publishing |location=New York, NY |isbn=978-0-7615-3157-9 |year=2000 |page=30}}</ref> |

||

The hero eventually defeats the Dragonlord and, triumphant, returns to Tantegel Castle, where King Lorik offers his kingdom to him as a reward. However, the hero turns down the offer, opting instead to find his own kingdom elsewhere. He then sets off with Princess Gwaelin to the rest of the world in search of a new land. This sets the stage for the events in ''[[Dragon Warrior II|Dragon Warrior II]]'' which take place many years later, where players take control of three of the hero's descendants.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /><ref>{{cite book|title=Dragon Warrior I & II| |

The hero eventually defeats the Dragonlord and, triumphant, returns to Tantegel Castle, where King Lorik offers his kingdom to him as a reward. However, the hero turns down the offer, opting instead to find his own kingdom elsewhere. He then sets off with Princess Gwaelin to the rest of the world in search of a new land. This sets the stage for the events in ''[[Dragon Warrior II|Dragon Warrior II]]'' which take place many years later, where players take control of three of the hero's descendants.<ref name="DWExplorerHandbook" /><ref>{{cite book|title=Dragon Warrior I & II Official Strategy Guide |publisher=Prima Publishing |location=New York, NY |isbn=978-0-7615-3157-9 |year=2000 |page=6}}</ref><ref>{{cite manual |section=The Story of ''Dragon Warrior'' | title=Dragon Warrior II: Instruction Booklet |year=1990 |publisher=[[Enix]] |location=Redmond, WA |id=NES-D2-USA |page=5}}</ref> |

||

==Characters== |

==Characters== |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

===Hero=== |

===Hero=== |

||

The Hero, who comes from another land,<ref name=DWSG5>{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior: Strategy Guide | |

The Hero, who comes from another land,<ref name=DWSG5>{{cite book |title=Dragon Warrior: Strategy Guide |last=Pelland |first=Scott |publisher=Nintendo of America |location=Redmond, WA |year=1989 |oclc=30018721 |page=5}}</ref> is a descendant of the legendary Erdrick.<ref>{{cite book|title=Dragon Warrior I & II Official Strategy Guide |publisher=Prima Publishing |location=New York, NY |isbn=978-0-7615-3157-9 |year=2000 |page=5}}</ref><ref name="np7_40">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=July/August|year=1989|issue=7|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |pages=39–50 |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582}}</ref> Upon his arrival, he did not appear to be a warrior—he came without weapon or armor—and was ignorant of the situation. The populous thought his claims to defeat the Dragonlord were preposterous; however, King Lorik, saw something to give him hope and aided him on his quest.<ref name=DWSG5/> |

||

===Dragonlord=== |

===Dragonlord=== |

||

The Dragonlord is a dragon from Charlock Castle whose soul became evil by learning magic.<ref name="np6_52">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1989| |

The Dragonlord is a dragon from Charlock Castle whose soul became evil by learning magic.<ref name="np6_52">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1989|issue=6|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582 |pages=52–53}}</ref> It was rumored that, through a spy network, he knew everything that happened in Alefgard.<ref name=DWSG5/> He sought "unlimited power and destruction",<ref name="np6_52"/> which resulted in a rising tide of evil throughout Alefgard.<ref name="manual56" /> The Dragonlord's intention is to enslave the world with his army of monsters which were guided by his will.<ref name=DW1NES/><ref name=DWSG5/> He rules from Charlock Castle, visible from Tantegel Castle, the starting point of the game.<ref name=DW1NES/><ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> |

||

==Development and release== |

==Development and release== |

||

[[Yuji Horii]] and his team at [[Chunsoft]] began production of ''Dragon Quest'' in 1985.<ref name=Essential50>{{cite web | url=http://www.1up.com/features/essential-50-dragon-warrior | title=20. Dragon Warrior: Though Art a Hero | accessdate=March 26, 2011 | author=Gifford, Kevin | work=The Essential 50 Archives: The Most Important Games Ever Made | publisher=[[1-up]]}}</ref> It was released in Japan in 1986 for the Famicom and [[MSX]].<ref name=Dragon-Warrior>{{cite GameFAQs|id=3133890|title=Dragon Warrior|date=January 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite GameFAQs|id=918072|title=Dragon Warrior|date=January 31, 2010}}</ref> ''Dragon Quest'' has been released on multiple platforms since its initial release, including in Japan in 2004 as a generic [[mobile phone]] game with updated graphics similar to those of ''[[Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Reverie|Dragon Quest VI]]''.<ref>{{cite web | year=2004 | title=Dragon Quest for Mobile Phones | url=http://www.gamespot.com/mobile/rpg/dragonquest/index.html|accessdate=October 14, 2007}}</ref> |

[[Yuji Horii]] and his team at [[Chunsoft]] began production of ''Dragon Quest'' in 1985.<ref name=Essential50>{{cite web | url=http://www.1up.com/features/essential-50-dragon-warrior | title=20. Dragon Warrior: Though Art a Hero | accessdate=March 26, 2011 | author=Gifford, Kevin | work=The Essential 50 Archives: The Most Important Games Ever Made | publisher=[[1-up]]}}</ref> It was released in Japan in 1986 for the Famicom and [[MSX]].<ref name=Dragon-Warrior>{{cite GameFAQs|id=3133890|title=Dragon Warrior|date=January 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite GameFAQs|id=918072|title=Dragon Warrior|date=January 31, 2010}}</ref> ''Dragon Quest'' has been released on multiple platforms since its initial release, including in Japan in 2004 as a generic [[mobile phone]] game with updated graphics similar to those of ''[[Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Reverie|Dragon Quest VI]]''.<ref>{{cite web | year=2004 | title=Dragon Quest for Mobile Phones |publisher=[[GameSpot]] | url=http://www.gamespot.com/mobile/rpg/dragonquest/index.html|accessdate=October 14, 2007}}</ref> |

||

Horii's earliest influence behind ''Dragon Quest'' was his own 1983 [[visual novel]] ''[[Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken|Portopia Serial Murder Case]]''<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto>{{cite book|first1=Goro|last1=Gotemba|year=2006|title=Japan on the Upswing: Why the Bubble Burst and Japan's Economic Renewal|page=201|publisher=Algora|isbn= 0-87586-462-5}}</ref> – a murder mystery game in which [[1-up]] described as "equal parts ''[[King's Quest]]'' and [[Sam Spade]]", bearing similarities to [[ICOM Simulations]]'s 1985 point-and-click adventure ''[[Déjà Vu (video game)|Déjà Vu]]''. He wanted to advance the game's storyline by using dialogue. ''Portopia'' was originally released for Japan's [[NEC PC-6001]] and was later [[porting|ported]] to the [[Famicom]] in 1985. In the port, Horii reworked the interface, including usage of the directional pad and the buttons to navigate the menus to accommodate for the console's limited controls. While ''Portopia'' did not directly result in the creation of ''Dragon Quest'', according to 1-up, the murder mystery "served as a proving ground" for the latter.<ref name="1UP.com">{{cite web |title=East and West, Warrior and Quest: A ''Dragon Quest'' Retrospective |publisher=[[1-up]] |accessdate=July 5, 2011 |url=http://www.1up.com/features/dragon-quest-retrospective}}</ref> |

Horii's earliest influence behind ''Dragon Quest'' was his own 1983 [[visual novel]] ''[[Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken|Portopia Serial Murder Case]]''<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto>{{cite book|first1=Goro|last1=Gotemba|year=2006|title=Japan on the Upswing: Why the Bubble Burst and Japan's Economic Renewal|page=201|publisher=Algora|isbn= 0-87586-462-5}}</ref> – a murder mystery game in which [[1-up]] described as "equal parts ''[[King's Quest]]'' and [[Sam Spade]]", bearing similarities to [[ICOM Simulations]]'s 1985 point-and-click adventure ''[[Déjà Vu (video game)|Déjà Vu]]''. He wanted to advance the game's storyline by using dialogue. ''Portopia'' was originally released for Japan's [[NEC PC-6001]] and was later [[porting|ported]] to the [[Famicom]] in 1985. In the port, Horii reworked the interface, including usage of the directional pad and the buttons to navigate the menus to accommodate for the console's limited controls. While ''Portopia'' did not directly result in the creation of ''Dragon Quest'', according to 1-up, the murder mystery "served as a proving ground" for the latter.<ref name="1UP.com">{{cite web |title=East and West, Warrior and Quest: A ''Dragon Quest'' Retrospective |publisher=[[1-up]] |accessdate=July 5, 2011 |url=http://www.1up.com/features/dragon-quest-retrospective}}</ref> |

||

The original idea for ''Dragon Quest'' came at a [[Macworld Conference & Expo]], when Horii came across [[Sir-Tech]]'s ''[[Wizardry]]'' and liked the game's depth and visuals. Afterwards he wanted to create for Chunsoft a game similar to ''Wizardry'' and to expose the mainly Western-exclusive RPG genre to Japan.<ref name="1UP.com" /> Along with ''Wizardry'', he cited ''[[Ultima (series)|Ultima]]'' as another inspiration for ''Dragon Quest''{{'}}s gameplay,<ref name="EGM">{{cite journal|last=Johnston |first=Chris |last2=Ricciardi |first2=John |last3=Ohbuchi|first3=Yotaka |date=December 1, 2001 |title=Role-Playing 101: Dragon Warrior|journal=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |pages=48–51 }}</ref><ref name="np238_84" /> specifically the [[First person (video games)|first-person]] [[Random encounter|random battles]] in the former and the [[Overhead perspective|overhead]] movement in [[Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness|the latter]].<ref name=kurt/> At this time, the RPG genre was predominantly Western and was limited to [[Personal computer|PC]]s; however, alongside ports of Western RPGs, Japanese gamers enjoyed "home-grown" games such as [[Henk Rogers]]'s ''[[The Black Onyx]]'' and [[Nihon Falcom]]'s ''[[Dragon Slayer (series)|Dragon Slayer]]'' series. To that end, he wanted to introduce the concept of role-playing video games, limited at the time to a niche computer audience, to a much wider audience in Japan;<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> his goal was to create a console RPG which retained the same elements commonly found in many computer-based RPGs at the time. According to Horii: "There was no keyboard, and the system was much simpler, using just a [game] controller. But I still thought that it would be really exciting for the player to play as their alter ego in the game. I personally was playing ''Wizardry'' and ''Ultima'' at the time, and I really enjoyed seeing my own self in the game."<ref name="1UP.com" /> |

The original idea for ''Dragon Quest'' came at a [[Macworld Conference & Expo]], when Horii came across [[Sir-Tech]]'s ''[[Wizardry]]'' and liked the game's depth and visuals. Afterwards he wanted to create for Chunsoft a game similar to ''Wizardry'' and to expose the mainly Western-exclusive RPG genre to Japan.<ref name="1UP.com" /> Along with ''Wizardry'', he cited ''[[Ultima (series)|Ultima]]'' as another inspiration for ''Dragon Quest''{{'}}s gameplay,<ref name="EGM">{{cite journal|last=Johnston |first=Chris |last2=Ricciardi |first2=John |last3=Ohbuchi|first3=Yotaka |date=December 1, 2001 |title=Role-Playing 101: Dragon Warrior|journal=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |publisher=Sendai Publications |location=Lombard, IL |issn=1058-918X |oclc=23857173|pages=48–51 }}</ref><ref name="np238_84" /> specifically the [[First person (video games)|first-person]] [[Random encounter|random battles]] in the former and the [[Overhead perspective|overhead]] movement in [[Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness|the latter]].<ref name=kurt/> At this time, the RPG genre was predominantly Western and was limited to [[Personal computer|PC]]s; however, alongside ports of Western RPGs, Japanese gamers enjoyed "home-grown" games such as [[Henk Rogers]]'s ''[[The Black Onyx]]'' and [[Nihon Falcom]]'s ''[[Dragon Slayer (series)|Dragon Slayer]]'' series. To that end, he wanted to introduce the concept of role-playing video games, limited at the time to a niche computer audience, to a much wider audience in Japan;<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> his goal was to create a console RPG which retained the same elements commonly found in many computer-based RPGs at the time. According to Horii: "There was no keyboard, and the system was much simpler, using just a [game] controller. But I still thought that it would be really exciting for the player to play as their alter ego in the game. I personally was playing ''Wizardry'' and ''Ultima'' at the time, and I really enjoyed seeing my own self in the game."<ref name="1UP.com" /> |

||

{{Quote box|quote=At the time I first made ''Dragon Quest'', computer and video game RPGs were still very much in the realm of hardcore fans and not very accessible to other players. So I decided to create a system that was easy to understand and emotionally involving, and then placed my story within that framework.|source=[[Yuji Horii]] on the design of the first ''Dragon Quest''<ref name="npinterview"/>|width=40%|align=left}} |

{{Quote box|quote=At the time I first made ''Dragon Quest'', computer and video game RPGs were still very much in the realm of hardcore fans and not very accessible to other players. So I decided to create a system that was easy to understand and emotionally involving, and then placed my story within that framework.|source=[[Yuji Horii]] on the design of the first ''Dragon Quest''<ref name="npinterview"/>|width=40%|align=left}} |

||

In order to create an RPG that would appeal to a wider audience unfamiliar with the genre or video games in general, Horii wanted to create a new kind of RPG that didn't rely on previous ''[[Dungeons & Dragons]]'' (''D&D'') experience, that didn't require hundreds of hours of rote fighting, and that could appeal to any kind of gamer. He wanted to build on ''Portopia'' and place a greater emphasis on storytelling and emotional involvement. He developed a [[coming of age]] tale which audiences could relate to, making use of RPG level-building gameplay as a way to represent this.<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto/><ref name="npinterview">{{cite book | |

In order to create an RPG that would appeal to a wider audience unfamiliar with the genre or video games in general, Horii wanted to create a new kind of RPG that didn't rely on previous ''[[Dungeons & Dragons]]'' (''D&D'') experience, that didn't require hundreds of hours of rote fighting, and that could appeal to any kind of gamer. He wanted to build on ''Portopia'' and place a greater emphasis on storytelling and emotional involvement. He developed a [[coming of age]] tale which audiences could relate to, making use of RPG level-building gameplay as a way to represent this.<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto/><ref name="npinterview">{{cite book |last=Horii |first=Yuji |authorlink=Yuji Horii |magazine=Nintendo Power |issue=221 |date=November 2007 |publisher=[[Future US]] |location=[[South San Francisco, CA]] |issn=1041-9551 |pages=78–80|quote=At the time I first made ''Dragon Quest'', computer and video game RPGs were still very much in the realm of hardcore fans and not very accessible to other players. So I decided to create a system that was easy to understand and emotionally involving, and then placed my story within that framework.}}</ref> The game featured elements still found in most console RPGs such as the ability to obtain better equipment, major quests which intertwine with minor subquests, an incremental spell system, usage of hit points and experience points, and a medieval theme.<ref name="gspot_consolehist_a">{{cite web |last=Vestal |first=Andrew |title=The History of Console RPGs – ''Dragon Quest'' |publisher=[[GameSpot]] |date=November 2, 1998 |accessdate=July 11, 2011 |url=http://uk.gamespot.com/features/vgs/universal/rpg_hs/nes1.html}}</ref> |

||

Horii believed the Famicom was the ideal venue for ''Dragon Quest'' because, unlike [[arcade game]]s, players did not have to worry about spending money if they got a [[game over]], and they could continue playing from where they left off. Horii wanted to include multiple [[player character]]s, but due to memory constraints, he was forced to use only one. He was aware that role-playing video games had a higher learning curve than other video games of the time. To compensate for this, he implemented quick level-ups at the start and gave players a clear final goal which is visible from the starting point on the world map: the Dragonlord's castle. He also provided a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve the final objective.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> He created an open world which is not blocked physically in any way except by monsters that can easily kill unprepared players – something in which [[Gamasutra]] described as one of the earliest examples of [[nonlinear gameplay]]. Horii utilized bridges to signify a change in difficulty; he also used a level progression with a high starting growth rate that decelerates over time, in contrast to the random initial stats and constant growth rates in the early editions of ''D&D''.<ref name=DQ-III>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1902/game_design_essentials_20_open_.php?page=8|author=Harris, John|title=Game Design Essentials: 20 Open World Games|page=8|publisher=Gamasutra|date=September 26, 2007|accessdate=January 31, 2011}}</ref> |

Horii believed the Famicom was the ideal venue for ''Dragon Quest'' because, unlike [[arcade game]]s, players did not have to worry about spending money if they got a [[game over]], and they could continue playing from where they left off. Horii wanted to include multiple [[player character]]s, but due to memory constraints, he was forced to use only one. He was aware that role-playing video games had a higher learning curve than other video games of the time. To compensate for this, he implemented quick level-ups at the start and gave players a clear final goal which is visible from the starting point on the world map: the Dragonlord's castle. He also provided a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve the final objective.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> He created an open world which is not blocked physically in any way except by monsters that can easily kill unprepared players – something in which [[Gamasutra]] described as one of the earliest examples of [[nonlinear gameplay]]. Horii utilized bridges to signify a change in difficulty; he also used a level progression with a high starting growth rate that decelerates over time, in contrast to the random initial stats and constant growth rates in the early editions of ''D&D''.<ref name=DQ-III>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1902/game_design_essentials_20_open_.php?page=8|author=Harris, John|title=Game Design Essentials: 20 Open World Games|page=8|publisher=Gamasutra|date=September 26, 2007|accessdate=January 31, 2011}}</ref> |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

[[File:Dq comparison side.png|frame|''Dragon Quest'' (left) and ''Dragon Warrior'' (right) had noticeable graphical differences.]] |

[[File:Dq comparison side.png|frame|''Dragon Quest'' (left) and ''Dragon Warrior'' (right) had noticeable graphical differences.]] |

||

First coverage of the localization of ''Dragon Quest'' in North America, appeared as a preview in the Winter 1988 issue of ''[[Nintendo Fun Club News]]'' – the precursor to the company's [[house organ]] ''[[Nintendo Power]]'' – where the title changed to ''Dragon Warrior''. |

First coverage of the localization of ''Dragon Quest'' in North America, appeared as a preview in the Winter 1988 issue of ''[[Nintendo Fun Club News]]'' – the precursor to the company's [[house organ]] ''[[Nintendo Power]]'' – where the title changed to ''Dragon Warrior''. |

||

The title was changed to avoid infringing on the trademark of the [[role-playing game (pen-and-paper)|pen-and-paper role-playing game]] ''[[DragonQuest]]'',{{#tag:ref|''DragonQuest'' was published by war-game publisher [[Simulations Publications]] in the 1980s until the company's [[bankruptcy]] in 1982. TSR, Inc. purchased the rights and continued publishing it as an alternative to ''D&D'' until 1987.<ref name="np238_84">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=February|year= |

The title was changed to avoid infringing on the trademark of the [[role-playing game (pen-and-paper)|pen-and-paper role-playing game]] ''[[DragonQuest]]'',{{#tag:ref|''DragonQuest'' was published by war-game publisher [[Simulations Publications]] in the 1980s until the company's [[bankruptcy]] in 1982. TSR, Inc. purchased the rights and continued publishing it as an alternative to ''D&D'' until 1987.<ref name="np238_84">{{Cite journal|journal=Nintendo Power|month=February|year=2008|issue=238|publisher=[[Future US]] |location=South San Francisco, CA |issn=1041-9551 |page=84}}</ref><ref name="spy">{{cite web | title=The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior |work=GameSpy |url=http://www.gamespy.com/articles/492/492001p1.html |page=1|accessdate=October 9, 2009}}</ref>|group=note}} although there was another pen-and-paper role-playing system called ''[[Dragon Warriors]]''.<ref>{{cite book|title=Dragon Warriors|first1=Dave|last1=Morris|authorlink1=Dave Morris|first2=Oliver|last2=Johnson|publisher=[[Corgi Books]]|year=1985|isbn=0-552-52287-2}}</ref> The article featured images from the Japanese version of the game as well as the protagonist's original name "Roto", the main villain's original name "Dragon King", and the original name of the game's starting location "Radatome Castle". The preview also mentioned the password system used to save games and how players needed to obtain the "Mantra of Resurrection" in order to get passwords. It briefly explained the backstory and basic gameplay elements, comparing the game to ''[[The Legend of Zelda (video game)|The Legend of Zelda]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Sneak Peeks – ''Dragon Warrior'' |magazine=[[Nintendo Fun Club News]] |issue=4 |date=Winter 1988 |page=14}}</ref> The game would be later mentioned in ''Nintendo Power''{{'s}} "Pak Watch" preview section in March 1989, mentioning the release of ''[[Dragon Quest III|Dragon Quest III]]'' in Japan in the magazine's premiere issue in July 1988. It again mentioned the rename from ''Dragon Quest'' to ''Dragon Warrior'', how it inspired the two Japanese sequels, and how that its release was "still a ways off".<ref>{{cite journal |title=Pak Watch |magazine=Nintendo Power |publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issue=5 |date=March/April 1989 |page=103 |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582}}</ref> |

||

''Dragon Warrior'' was [[Software localization|localized]] for North American release in August [[1989 in video gaming|1989]];<ref name=Dragon-Warrior/> Because the game was released in North America nearly three years after the original Japanese version, the graphics were improved. Instead of lengthy [[password (video games)|password]]s with [[kana]] characters, the North American version featured a battery-backed RAM savegame.<ref name=kurt /> Akira Toriyama's artwork in the instruction booklets was also changed to reflect the more serious tone Enix wanted to convey to the North American audience; while the characters maintained the same poses, they adopted a more serious and mature look than in the Japanese versions.<ref name="ToriyamaArtwork" /> The game's character sprites were changed in that they face their direction of travel; in the Japanese versions, the sprites were smaller and only faced forward, and players had to choose a direction for actions from a menu. Spells were given self-explanatory one-word titles, as opposed to the made-up words in the Japanese version. Locations were renamed, and dialogue was rewritten in a pseudo-[[Elizabethan English]] style.<ref name=kurt/><ref name="np238_84"/> One of the more notable changes in the North American version involves a woman in the town in which the Hero must first buy keys; she sells tomatoes in the North American version rather than the sexually-explicit "puff puff" in the Japanese version<ref name="np238_84"/>{{#tag:ref|{{nihongo|Puff puff|ぱふぱふ|pafu pafu}} comes from the Japanese [[onomatopoeia]] for a girl rubbing her breasts in someone's faces, although it can also be used for the general term of a girl juggling her own breasts.<ref name=kurt/>|group=note}} – something that has been featured in later games in game's sequels as well as in the ''Dragon Ball'' series.<ref>{{cite web |last=Kauz |first=Andrew |title=The rubbing of breasts on faces in ''Dragon Quest IX'' |publisher=[[Destructoid]] |date=August 21, 2010 |accessdate=July 14, 2011 |url=http://www.destructoid.com/the-rubbing-of-breasts-on-faces-in-dragon-quest-ix-181483.phtml}}</ref> |

''Dragon Warrior'' was [[Software localization|localized]] for North American release in August [[1989 in video gaming|1989]];<ref name=Dragon-Warrior/> Because the game was released in North America nearly three years after the original Japanese version, the graphics were improved. Instead of lengthy [[password (video games)|password]]s with [[kana]] characters, the North American version featured a battery-backed RAM savegame.<ref name=kurt /> Akira Toriyama's artwork in the instruction booklets was also changed to reflect the more serious tone Enix wanted to convey to the North American audience; while the characters maintained the same poses, they adopted a more serious and mature look than in the Japanese versions.<ref name="ToriyamaArtwork" /> The game's character sprites were changed in that they face their direction of travel; in the Japanese versions, the sprites were smaller and only faced forward, and players had to choose a direction for actions from a menu. Spells were given self-explanatory one-word titles, as opposed to the made-up words in the Japanese version. Locations were renamed, and dialogue was rewritten in a pseudo-[[Elizabethan English]] style.<ref name=kurt/><ref name="np238_84"/> One of the more notable changes in the North American version involves a woman in the town in which the Hero must first buy keys; she sells tomatoes in the North American version rather than the sexually-explicit "puff puff" in the Japanese version<ref name="np238_84"/>{{#tag:ref|{{nihongo|Puff puff|ぱふぱふ|pafu pafu}} comes from the Japanese [[onomatopoeia]] for a girl rubbing her breasts in someone's faces, although it can also be used for the general term of a girl juggling her own breasts.<ref name=kurt/>|group=note}} – something that has been featured in later games in game's sequels as well as in the ''Dragon Ball'' series.<ref>{{cite web |last=Kauz |first=Andrew |title=The rubbing of breasts on faces in ''Dragon Quest IX'' |publisher=[[Destructoid]] |date=August 21, 2010 |accessdate=July 14, 2011 |url=http://www.destructoid.com/the-rubbing-of-breasts-on-faces-in-dragon-quest-ix-181483.phtml}}</ref> |

||

In June 1989, ''[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]]''{{'}}s "Quartermann" announced that ''Dragon Quest'' would be Nintendo's "big release" in North America that Christmas. He mentioned the series' immense popularity in Japan as a reason for the game's projected popularity in the Western market; he said that when ''Dragon Quest III'' was released earlier that year in Japan, over 300 schoolchildren were arrested for [[truancy]] while waiting in stores for the game to be released.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Quartermann |title=Gaming Gossip |magazine=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |issue=2 |date=June 1989 |page=26 |publisher=Sendai Publications |location=[[Lombard, IL]]}}</ref> As a result, Japan passed a law that required all future ''Dragon Quest'' titles to be released on either Sundays or national holidays.<ref>{{cite web |last=Casamassina |first=Matt |title=State of the RPG: GameCube |publisher=IGN |date=July 19, 2005 |accessdate=July 22, 2011 |url=http://cube.ign.com/articles/634/634965p1.html}}</ref> However, in the following issue, Quartermann noted that the game, now renamed ''Dragon Warrior'', wasn't "that special at all" and told others to play the NES version of ''[[Ultima III: Exodus|Ultima III: Exodus]]'', which he said was virtually identical.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Quartermann |title=Gaming Gossip |magazine=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |issue=3 |date=September 1989 |page=28 |publisher=Sendai Publications |location=Lombard, IL}}</ref> |

In June 1989, ''[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]]''{{'}}s "Quartermann" announced that ''Dragon Quest'' would be Nintendo's "big release" in North America that Christmas. He mentioned the series' immense popularity in Japan as a reason for the game's projected popularity in the Western market; he said that when ''Dragon Quest III'' was released earlier that year in Japan, over 300 schoolchildren were arrested for [[truancy]] while waiting in stores for the game to be released.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Quartermann |title=Gaming Gossip |magazine=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |issue=2 |date=June 1989 |page=26 |publisher=Sendai Publications |location=[[Lombard, IL]] |issn=1058-918X |oclc=23857173}}</ref> As a result, Japan passed a law that required all future ''Dragon Quest'' titles to be released on either Sundays or national holidays.<ref>{{cite web |last=Casamassina |first=Matt |title=State of the RPG: GameCube |publisher=IGN |date=July 19, 2005 |accessdate=July 22, 2011 |url=http://cube.ign.com/articles/634/634965p1.html}}</ref> However, in the following issue, Quartermann noted that the game, now renamed ''Dragon Warrior'', wasn't "that special at all" and told others to play the NES version of ''[[Ultima III: Exodus|Ultima III: Exodus]]'', which he said was virtually identical.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Quartermann |title=Gaming Gossip |magazine=[[Electronic Gaming Monthly]] |issue=3 |date=September 1989 |page=28 |publisher=Sendai Publications |location=Lombard, IL |issn=1058-918X |oclc=23857173}}</ref> |

||

''[[Nintendo Power]]'' provided three feature articles on ''Dragon Warrior'', from May to October 1989;<ref name=np6_52/><ref name=np7_40/><ref |

''[[Nintendo Power]]'' provided three feature articles on ''Dragon Warrior'', from May to October 1989;<ref name=np6_52/><ref name=np7_40/><ref name="NP8" /> the November/December 1989 issue provided a [[strategy guide]].<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Table of Contents|journal=Nintendo Power|month=November/December|year=1989|issue=9|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=5}}</ref> In March/April 1990, the magazine provided a map of ''Dragon Warrior'', with a poster of ''[[Super Contra]]'' on the other side; the issue also featured a ''Dragon Warrior'' text adventure.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=''Dragon Warrior'' Text Adventure|journal=Nintendo Power|month=March/April|year=1990|issue=11|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|pages=51–54}}</ref> Late that year, ''Nintendo Power'' gave away free copies of ''Dragon Warrior'' to subscribers, along with a card which explains the equipment, monsters, levels, and locations.<ref name="1UP.com" /> Also included was a 64-page "Explorer's Handbook" which gave a full walkthrough of the game as well as additional backstory that was not mentioned in the original instruction booklet.<ref>{{cite book |title=''Dragon Warrior'' Explorer's Handbook |publisher=Nintendo |year=1989}}</ref> According to 1UP.com, Nintendo was desperate to get rid of unwanted copies of the game, so they gave them away for free to subscribers.<ref name="1UP-flops">{{cite web |last=Mackey |first=Bob |title=Smart Bombs: Celebrating Gaming's Most Beloved Flops |publisher=1UP.com |date=February 5, 2007 |accessdate=July 11, 2011 |url=http://www.1up.com/features/smart-bombs |page=2}}</ref> The giveaway attracted nearly 500,000 new subscribers and has ultimately led to the series' success in the Western market.<ref name="1UP-flops" /><ref>{{cite journal |title=50 Issues of ''Nintendo Power'': A View from Inside Out |magazine=Nintendo Power |publisher=Tokuma Shoten |issue=50 |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582 |page=39}}</ref> Brief mention of the subscription bonus was made in the magazine's January 1996 issue, when it was announced that Enix was closing its American division.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Epic Center – Enix on a Quest|journal=Nintendo Power|month=January|year=1996|issue=80|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582 |page=58}}</ref> |

||

===Re-releases=== |

===Re-releases=== |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

''Dragon Quest'' was extremely popular in Japan and became the first in a series that, {{as of|2011|lc=y}}, includes nine games with several spin-off series and stand-alone titles. The Famicom version sold 1.5 million copies, while the ''Dragon Quest I & II'' remake for the Super Famicom sold 1.2 million copies.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.the-magicbox.com/Chart-JPPlatinum.shtml | title=Japan Platinum Game Chart (Games sold over Million Copies) | publisher=The Magicbox | accessdate=April 18, 2011 | at=Enix}}</ref> The release of ''Dragon Quest'' has been regarded as a milestone in the history of the console RPG.<ref name=Essential50/><ref name="spy"/> It has since been cited by [[GameSpot]] as one of the fifteen most influential titles in the history of video games.<ref name="Gamespot top15">{{cite web | year=2005 | title=15 Most Influential Games|archiveurl=http://replay.waybackmachine.org/20090610012514/http://gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/15influential/p11_01.html|archivedate=June 10, 2009|url=http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/15influential/p11_01.html|publisher=[[GameSpot]]|accessdate=September 1, 2009}}</ref> [[IGN]] listed it as the eighth best NES game of all time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ign.com/top-100-nes-games/8.html|title=Top 100 NES Games of all Time|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20091028131723/www.ign.com/top-100-nes-games/index.html|archivedate=October 28, 2009|first=Colin|last=Moriarty|publisher=IGN|accessdate=October 16, 2009}}</ref> In 2005, they listed it as the 92nd-best game of all time,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://top100.ign.com/2005/091-100.html|title=091-100|work=Top 100 Games of all Time|publisher=IGN|date=July 29, 2005|accessdate=October 27, 2009}}</ref> and in a 2007 version of the list, they listed it as the 29th best.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://top100.ign.com/2007/ign_top_game_29.html|title=Dragon Warrior|work=Top 100 Games of all Time|publisher=IGN|date=December 3, 2007 |accessdate=October 27, 2009}}</ref> |

''Dragon Quest'' was extremely popular in Japan and became the first in a series that, {{as of|2011|lc=y}}, includes nine games with several spin-off series and stand-alone titles. The Famicom version sold 1.5 million copies, while the ''Dragon Quest I & II'' remake for the Super Famicom sold 1.2 million copies.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.the-magicbox.com/Chart-JPPlatinum.shtml | title=Japan Platinum Game Chart (Games sold over Million Copies) | publisher=The Magicbox | accessdate=April 18, 2011 | at=Enix}}</ref> The release of ''Dragon Quest'' has been regarded as a milestone in the history of the console RPG.<ref name=Essential50/><ref name="spy"/> It has since been cited by [[GameSpot]] as one of the fifteen most influential titles in the history of video games.<ref name="Gamespot top15">{{cite web | year=2005 | title=15 Most Influential Games|archiveurl=http://replay.waybackmachine.org/20090610012514/http://gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/15influential/p11_01.html|archivedate=June 10, 2009|url=http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/15influential/p11_01.html|publisher=[[GameSpot]]|accessdate=September 1, 2009}}</ref> [[IGN]] listed it as the eighth best NES game of all time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ign.com/top-100-nes-games/8.html|title=Top 100 NES Games of all Time|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20091028131723/www.ign.com/top-100-nes-games/index.html|archivedate=October 28, 2009|first=Colin|last=Moriarty|publisher=IGN|accessdate=October 16, 2009}}</ref> In 2005, they listed it as the 92nd-best game of all time,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://top100.ign.com/2005/091-100.html|title=091-100|work=Top 100 Games of all Time|publisher=IGN|date=July 29, 2005|accessdate=October 27, 2009}}</ref> and in a 2007 version of the list, they listed it as the 29th best.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://top100.ign.com/2007/ign_top_game_29.html|title=Dragon Warrior|work=Top 100 Games of all Time|publisher=IGN|date=December 3, 2007 |accessdate=October 27, 2009}}</ref> |

||

''Dragon Warrior'' debuted at #7 on its bimonthly "Top 30" top NES games list in November 1989.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=November/December|year=1989|issue=9|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=81}}</ref> It climbed to #5 in January 1990 and remained there for 4 months;<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=January/February|year=1990|issue=10|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=49}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=March/April|year=1990|issue=11|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=41}}</ref> it then dropped to #11 in May,<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1990|issue=12|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=43}}</ref> #14 in July,<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=July/August|year=1990|issue=14|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=67}}</ref> and #16 in September 1990 before it dropped off the list.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=September/October|year=1990|issue=16|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|page=23}}</ref> In the "''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89", the game was nominated for "Best Theme, Fun" and "Best Overall";<ref>{{Cite journal|title=''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89|journal=Nintendo Power|month=March/April|year=1990|issue=11|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|pages=98–99}}</ref> it failed to win in either category.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1990|issue=12|publisher=Tokuma Shoten|pages=26–29}}</ref> |

''Dragon Warrior'' debuted at #7 on its bimonthly "Top 30" top NES games list in November 1989.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=November/December|year=1989|issue=9|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=81}}</ref> It climbed to #5 in January 1990 and remained there for 4 months;<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=January/February|year=1990|issue=10|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=49}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=March/April|year=1990|issue=11|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=41}}</ref> it then dropped to #11 in May,<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1990|issue=12|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=43}}</ref> #14 in July,<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=July/August|year=1990|issue=14|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=67}}</ref> and #16 in September 1990 before it dropped off the list.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Top 30|journal=Nintendo Power|month=September/October|year=1990|issue=16|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|page=23}}</ref> In the "''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89", the game was nominated for "Best Theme, Fun" and "Best Overall";<ref>{{Cite journal|title=''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89|journal=Nintendo Power|month=March/April|year=1990|issue=11|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|pages=98–99}}</ref> it failed to win in either category.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=''Nintendo Power'' Awards '89|journal=Nintendo Power|month=May/June|year=1990|issue=12|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|pages=26–29}}</ref> |

||

The initial NES version of ''Dragon Warrior'' was met with average results overall. ''[[Nintendo Power]]'' ranked the NES release of ''Dragon Warrior'' a 3/5 upon its original release;<ref name="np6_52"/> later they rated it the 140th-best game made on a Nintendo System in their Top 200 Games list in 2006.<ref name="NP Top 200">{{Cite journal| |

The initial NES version of ''Dragon Warrior'' was met with average results overall. ''[[Nintendo Power]]'' ranked the NES release of ''Dragon Warrior'' a 3/5 upon its original release;<ref name="np6_52"/> later they rated it the 140th-best game made on a Nintendo System in their Top 200 Games list in 2006.<ref name="NP Top 200">{{Cite journal|title=''Nintendo Power''{{'}}s Top 200 All-Time Games|magazine=Nintendo Power|month=February|year=2006|issue=200|publisher=Tokuma Shoten |location=Redmond, WA |issn=1041-9551 |oclc=18893582|pages=58–66}}</ref> IGN reviewed the game years later and gave it a 7.8/10,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://cheats.ign.com/objects/006/006015.html|title=Dragon Warrior|publisher=IGN|accessdate=December 5, 2009}}</ref> RPGamer's Bill Johnson gave it an overall score of 4/5.<ref name=Johnson/><ref name=Roku>{{cite web | url=http://www.rpgamer.com/games/dq/dq1/reviews/dq1strev2.html | title=Here's a Stick, Go Save the World | publisher=RPGamer | accessdate=April 14, 2011 | author=Calvin, Derek "Roku"}} |

||

</ref> The NES's localization has received considerable praise for adding extra characters and depth to the story.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/> The removal of the stylized dialogue in the GBC remake has similarly been lamented.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> |

</ref> The NES's localization has received considerable praise for adding extra characters and depth to the story.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/> The removal of the stylized dialogue in the GBC remake has similarly been lamented.<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> |

||

Seemingly primitive by today's standards, ''Dragon Warrior'' features one-on-one combat, a limited array of items and equipment, ten spells, five towns, and five dungeons.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/><ref name="Guide 6/105"/><ref name=np7_40/> 1UP.com explained why the series was not immensely popular at first in North America; American console gamers were not used to the idea of RPGs, and they said that would take a decade for the genre to be "flashy enough to distract from all of those words they made you read".<ref name="1UP-flops" /> Chi Kong Lui of GameCritics commented on how the game added "realism" to video games, writing: "If a player perished in ''Dragon Warrior'', he or she had to suffer the dire consequences of losing progress and precious gold. That element of death evoked a sense of instinctive fear and tension for survival."<ref name=Gamecritics>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamecritics.com/review/dragonwarr12/main.php |title=Dragon Warrior I & II |author=Chi Kong Lui |publisher=GameCritics |accessdate=October 6, 2009}}</ref> This, he said, allowed players to identify with the main character on a much larger scale. IGN writer Mark Nix compared the game's seemingly archaic plot to more modern RPGs; he said: "Noble blood means nothing when the society is capitalist, aristocratic, or militaristic. Damsels don't need rescuing – they need a battle axe and some magic tutoring in the field."<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> While reviewing ''[[Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King|Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King]]'', [[GameSpy]] staff wrote that, for many gamers, ''Dragon Warrior'' was their first exposure to the console RPG. Recalling their past, one of the staff members commented: {{quote|"It opened my eyes to a fun new type of gameplay. Suddenly strategy (or at least pressing the "A" button) was more important than reflex, and the story was slightly (slightly!) more complex than the 'rescue the princess' stuff I'd seen up 'till then. After all, Dragon Warrior was only half-over when you rescued its princess."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamespy.com/articles/618/618469p8.html|title= The Annual E3 Awards 2005|publisher=GameSpy |accessdate=October 9, 2009}}</ref>}} Bill Johnson compared ''Dragon Warrior'' to modern RPGs by noting the complete lack of replay value, which is due as much to the requirement that almost everything in the game must be done to beat it as to its difficulty. Johnson still noted the game's historical importance; he said: "[Playing ''Dragon Warrior'' is] a tough road to walk, but reaching its end will instill a new appreciation of what today's RPG's are all about."<ref name=Johnson/> In a column called "Play Back", ''Nintendo Power'' reflected on the game, naming its historical significance as its greatest aspect; it noted that "playing ''Dragon Warrior'' these days can be a bit of a chore".<ref name="np238_84"/> |

Seemingly primitive by today's standards, ''Dragon Warrior'' features one-on-one combat, a limited array of items and equipment, ten spells, five towns, and five dungeons.<ref name=kurt/><ref name=Johnson/><ref name="Guide 6/105"/><ref name=np7_40/> 1UP.com explained why the series was not immensely popular at first in North America; American console gamers were not used to the idea of RPGs, and they said that would take a decade for the genre to be "flashy enough to distract from all of those words they made you read".<ref name="1UP-flops" /> Chi Kong Lui of GameCritics commented on how the game added "realism" to video games, writing: "If a player perished in ''Dragon Warrior'', he or she had to suffer the dire consequences of losing progress and precious gold. That element of death evoked a sense of instinctive fear and tension for survival."<ref name=Gamecritics>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamecritics.com/review/dragonwarr12/main.php |title=Dragon Warrior I & II |author=Chi Kong Lui |publisher=GameCritics |date=March 2, 2001 |accessdate=October 6, 2009}}</ref> This, he said, allowed players to identify with the main character on a much larger scale. IGN writer Mark Nix compared the game's seemingly archaic plot to more modern RPGs; he said: "Noble blood means nothing when the society is capitalist, aristocratic, or militaristic. Damsels don't need rescuing – they need a battle axe and some magic tutoring in the field."<ref name=":IGN DW1&2"/> While reviewing ''[[Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King|Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King]]'', [[GameSpy]] staff wrote that, for many gamers, ''Dragon Warrior'' was their first exposure to the console RPG. Recalling their past, one of the staff members commented: {{quote|"It opened my eyes to a fun new type of gameplay. Suddenly strategy (or at least pressing the "A" button) was more important than reflex, and the story was slightly (slightly!) more complex than the 'rescue the princess' stuff I'd seen up 'till then. After all, Dragon Warrior was only half-over when you rescued its princess."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gamespy.com/articles/618/618469p8.html|title= The Annual E3 Awards 2005|publisher=GameSpy |accessdate=October 9, 2009}}</ref>}} Bill Johnson compared ''Dragon Warrior'' to modern RPGs by noting the complete lack of replay value, which is due as much to the requirement that almost everything in the game must be done to beat it as to its difficulty. Johnson still noted the game's historical importance; he said: "[Playing ''Dragon Warrior'' is] a tough road to walk, but reaching its end will instill a new appreciation of what today's RPG's are all about."<ref name=Johnson/> In a column called "Play Back", ''Nintendo Power'' reflected on the game, naming its historical significance as its greatest aspect; it noted that "playing ''Dragon Warrior'' these days can be a bit of a chore".<ref name="np238_84"/> |

||

===Remakes=== |

===Remakes=== |

||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

==Impact on the RPG genre== |

==Impact on the RPG genre== |

||

{{Quote box|quote=Bits and pieces of Dragon Warrior had been seen in videogames before, but never all sewn up together so neatly. DW's incredible combination of gameplay elements established it as THE template for console RPGs to follow.|source=William Cassidy, The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior<ref name="spy-2"/>|width=35%|align=left}} |

{{Quote box|quote=Bits and pieces of Dragon Warrior had been seen in videogames before, but never all sewn up together so neatly. DW's incredible combination of gameplay elements established it as THE template for console RPGs to follow.|source=William Cassidy, The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior<ref name="spy-2"/>|width=35%|align=left}} |

||

The release of ''Dragon Warrior'' has been marked as one of the few notable turning points in [[History of video games|video game history]].<ref name=Essential50/> The game has been listed as a genre builder for RPGs, especially the console role-playing games sub-genre, which has influenced RPGs around the world.<ref name=Essential50/><ref name="spy"/> While parts of the game had been in previous RPGs titles, the game set the template for all others to follow; almost all of the elements of the game became the foundation for nearly every game of the genre to come, from gameplay to narrative.<ref name="spy"/><ref name=Gamecritics/><ref name="spy-2">{{cite web | title=The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior | work=GameSpy | url=http://www.gamespy.com/articles/492/492001p2.html |page=2 |accessdate=October 9, 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Andrew Vestal|title=Other Game Boy RPGs|publisher=GameSpot|date=November 2, 1998|url=http://uk.gamespot.com/features/vgs/universal/rpg_hs/gameboy3.html|accessdate=November 18, 2009}}</ref> When ''Dragon Warrior'' was released, many of the techniques used were intended to make up for hardware limitations; despite advances in technology which render some of those unnecessary, many of them have become [[Convention (norm)|conventions]] still used in today's RPGs.<ref name=Gamecritics/> It introduced the overhead 2D map, which became a hallmark of 2D RPGs to the point that most games with that setup are assumed to be an RPG. ''Dragon Warrior'' has also been credited with introducing the turn-based battle systems and with introducing storytelling as a prominent aspect to video games. While ''[[Final Fantasy (video game)|Final Fantasy]]'' has been considered more important due to its popularity and attention in North America, the fundamentals on which that game was based were laid down by ''Dragon Warrior''.<ref name="Gamespot top15"/><ref name="spy-2"/> In response to a survey, [[Gamasutra]] cited Quinton Klabon of [[Dartmouth College]] as saying that ''Dragon Warrior'' translated the ''D&D'' experience to video games and has set the genre standards to levels that have not changed since.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1809/the_gamasutra_quantum_leap_awards_.php| title=The Gamasutra Quantum Leap Awards: Role-Playing Games |accessdate=March 28, 2011 | publisher=Gamasutra | date=October 6, 2006 |work =Honorable Mention: Dragon Warrior}}</ref> |

The release of ''Dragon Warrior'' has been marked as one of the few notable turning points in [[History of video games|video game history]].<ref name=Essential50/> The game has been listed as a genre builder for RPGs, especially the console role-playing games sub-genre, which has influenced RPGs around the world.<ref name=Essential50/><ref name="spy"/> While parts of the game had been in previous RPGs titles, the game set the template for all others to follow; almost all of the elements of the game became the foundation for nearly every game of the genre to come, from gameplay to narrative.<ref name="spy"/><ref name=Gamecritics/><ref name="spy-2">{{cite web | title=The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior | work=GameSpy | url=http://www.gamespy.com/articles/492/492001p2.html |page=2 |accessdate=October 9, 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Andrew Vestal|title=Other Game Boy RPGs|publisher=GameSpot|date=November 2, 1998|url=http://uk.gamespot.com/features/vgs/universal/rpg_hs/gameboy3.html|accessdate=November 18, 2009}}</ref> When ''Dragon Warrior'' was released, many of the techniques used were intended to make up for hardware limitations; despite advances in technology which render some of those unnecessary, many of them have become [[Convention (norm)|conventions]] still used in today's RPGs.<ref name=Gamecritics/> It introduced the overhead 2D map, which became a hallmark of 2D RPGs to the point that most games with that setup are assumed to be an RPG. ''Dragon Warrior'' has also been credited with introducing the turn-based battle systems and with introducing storytelling as a prominent aspect to video games. While ''[[Final Fantasy (video game)|Final Fantasy]]'' has been considered more important due to its popularity and attention in North America, the fundamentals on which that game was based were laid down by ''Dragon Warrior''.<ref name="Gamespot top15"/><ref name="spy-2"/> In response to a survey, [[Gamasutra]] cited Quinton Klabon of [[Dartmouth College]] as saying that ''Dragon Warrior'' translated the ''D&D'' experience to video games and has set the genre standards to levels that have not changed since.<ref>{{cite web |last=Boyer |first=Brandon |last2=Cifaldi |first2=Frank |url=http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1809/the_gamasutra_quantum_leap_awards_.php| title=The Gamasutra Quantum Leap Awards: Role-Playing Games |accessdate=March 28, 2011 | publisher=Gamasutra | date=October 6, 2006 |work =Honorable Mention: Dragon Warrior}}</ref> |

||

In the November 2010 issue of ''Nintendo Power'', in celebration of the NES' 25th anniversary in North America, Yuji Horii recalled on the making of ''Dragon Warrior''. A fan of basic RPG mechanics, he sought to simplify the interfaces, saying that interfaces of many other RPGs at the time "were so complicated that they intimidated new users". He said that the simplified gameplay was what made the game appealing to people and was what made the franchise's success possible. Moreover, he heard from others at the time that the NES lacked sufficient capacity for RPGs, motivating him more to make one.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Horii |first=Yuji |title=25 Years of the NES |magazine=Nintendo Power |issue=260 |date=November |