Cheka: Difference between revisions

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

In September 1918, according to ''[[The Black Book of Communism]]'', in only twelve provinces of Russia, 48,735 deserters and 7,325 "bandits" were arrested, 1,826 were killed and 2,230 were executed. The exact identity of these individuals is confused by the fact that the Soviet Bolshevik government used the term 'bandit' to cover ordinary criminals as well as armed and unarmed political opponents, such as the anarchists. |

In September 1918, according to ''[[The Black Book of Communism]]'', in only twelve provinces of Russia, 48,735 deserters and 7,325 "bandits" were arrested, 1,826 were killed and 2,230 were executed. The exact identity of these individuals is confused by the fact that the Soviet Bolshevik government used the term 'bandit' to cover ordinary criminals as well as armed and unarmed political opponents, such as the anarchists. |

||

==Conflicts== |

|||

==Number of victims== |

|||

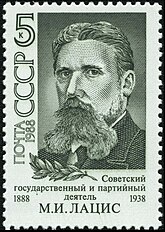

Estimates on Cheka executions vary widely. The lowest figures (''disputed below'') are provided by Dzerzhinsky's lieutenant [[Martin Latsis|Martyn Latsis]], limited to RSFSR over the period 1918–1920: |

|||

The Civil War intensified due to the Czechoslovak invasion May 1918 that was supported by the Entente powers,.<ref>Л. С. Гапоненко (ответственный редактор) ''Рабочий класс в Октябрьской революции и на защите ее завоеваний 1917 - 1920 гг.'' Наука. 1984. p. 222</ref> Massive White Terror against the Soviet forces intensified.<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.96</ref> The total number of victims of the White Terror in Central Russia at the hands of the Czechoslovaks and the SR-led Komuch regime amounted to more than 5000 people killed in the summer and autumn of 1918.<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.36</ref> After the White Cossacks led by Krasnov seized control of the Don Province, more than 40,000 people were killed by Krasnov's regime.<ref>[http://www.orenport.ru/docs/82/futor/index.html Футорянский Л. И. Казачество в огне гражданской войны в России (1918—1920 гг.). РИК ГОУ ОГУ, 2003]</ref> In the Samara region on May 5, 1918, Dutov's Cossack forces killed 675 people by execution and burying the victims alive.<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.105</ref> In the autumn of 1918, General Pokrovsky's forces killed 2500 people in the town of Maikop, while Ataman Annenkov's forces shot more than 1500 peasants in Slavgorod region.<ref>http://www.gumer.info/bibliotek_Buks/History/Rat/04.php</ref> The intensification in the summer of 1918 of massive and individual White Terror inevitably led to the revision of punitive-repressive policies of the Soviet government to an increase in repression. This policy more easily asserted itself with the more frequent reports of White Terror.<ref name="И. С. Ратьковский, p.144">И. С. Ратьковский, p.144</ref> |

|||

*For the period 1918-July 1919, covering only twenty provinces of central Russia: |

|||

::In 1918: 6,300; in 1919 (up to July): 2,089; Total: 8,389 |

|||

In addition to White Terror, individual terrorism against the Soviet forces significantly increased as 1918 progressed. In the summer of 1918 in Petrograd, Socialist-Revolutionary cells organized plots of assassinations against leading Soviet officials Volodarsky, Zinoviev, and Uritsky, as well as Lenin, Trotsky, and other officials of the Soviet state. The situation in Petrograd after the assassination of Soviet official Volodarsky showed the willingness of the population for mass repression, as seen in the slogans of banners during his funeral. In Petrograd on June 22, a Menshevik member Vasiliev was killed, motivated by revenge over the death of Volodarsky. Individual terror against the Soviet government killed 339 people. The end of August 1918 marked a new surge of individual terrorism directed against the Soviet state.<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.120</ref> |

|||

*For the whole period 1918-19: |

|||

::In 1918: 6,185; in 1919: 3,456; Total: 9,641 |

|||

St Petersburg University Professor studies the subject in his book ''The Red Terror in Russia in 1918''<ref>[http://www.pseudology.org/Abel/PetroVchk1918_RedTerror.pdf И. С. Ратьковский, Красный террор и деятельность ВЧК в 1918 году. СПб.: Изд-во С.-Петерб. ун-та, 2006.]</ref> |

|||

*For the whole period 1918-20: |

|||

::In January–June 1918: 22; in July–December 1918: more than 6,000; in 1918-20: 12,733. |

|||

During the Red Terror that began in early September 1918 and ended particularly after the issuing of an amnesty to prisoners on 7 November 1918, executions amounted to amounted to 8000 people. 2000 executions occurred from August 30 to 5 September 1918, and another 3000 during the remaining days of September. 3000 more were executed during October–November 1918. There were several stages of the Red Terror during the autumn of 1918. The first stage includes the period from 30 August 1918 to 5 September 1918, beginning with the attacks on Lenin and Uritsky and ending with the publication of the Red Terror decree. During this uncontrolled wave of repression, there were more than 3 thousand executions, especially in provincial towns and the frontier provinces. More organized repression took place during the remaining days of September. The total number of victims of the policy of Red Terror in this period was up to 2 thousand.<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.199</ref> |

|||

Experts generally agree these semi-official figures are vastly understated.<ref>pages 463-464, Leggett (1986).</ref> Pioneering historian of the [[Red Terror]] [[Sergei Melgunov]] claims that this was done deliberately in an attempt to demonstrate the government's humanity. For example, he refutes the claim made by Latsis that only 22 executions were carried out in the first six months of the Cheka's existence by providing evidence that the true number was 884 executions.<ref>[[Sergei Melgunov]], [http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/redterror.pdf "The Record of the Red Terror"], paulbogdanor.com.</ref> W. H. Chamberlin claims, "It is simply impossible to believe that the Cheka only put to death 12,733 people in all of Russia up to the end of the civil war."<ref name="Chamberlin">pages 74-75, Chamberlin (1935).</ref> [[Donald Rayfield]] concurs, noting that, "Plausible evidence reveals that the actual numbers . . . vastly exceeded the official figures."<ref>[[Donald Rayfield]]. ''[[Stalin and His Hangmen]]: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him.'' [[Random House]], 2004. ISBN 0-375-50632-2, p.1926: [http://books.google.com/books?id=Yi3ow3TU8-4C&lpg=PA1926&pg=RA2-PA1915#v=onepage&q&f=false GBYi].</ref> Chamberlin provides the "reasonable and probably moderate" estimate of 50,000,<ref name="Chamberlin"/> while others provide estimates ranging up to 500,000.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN1560008873&id=sK5CJFpb2DAC&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39&ots=TubCNy7NoM&dq=lethal+politics+cheka+executions+most+probably+about+500,000&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=X7A0DHHZ6WCVlnpj5m9CTB-u_rg page 39], Rummel (1990).</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/2273462.stm |title=Statue plan stirs Russian row (BBC) |publisher=BBC News |date=2002-09-21 |accessdate=2011-07-27}}</ref> Several scholars put the number of executions at about 250,000.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=9TWUAQ7Xof8C&pg=PA28 page 28], Andrew and Mitrokhin, ''The Sword and the Shield'', paperback edition, Basic books, 1999.</ref><ref>page 180, Overy, ''The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia,'' W. W. Norton & Company; 1st American Ed edition, 2004.</ref> Some believe it is possible more people were murdered by the Cheka than died in battle.<ref>page 649, Figes (1996).</ref> |

|||

Starting in October 1918, Red Terror policy experienced a crisis. With victories at the front and the growth of the revolutionary movement in Europe, the need for the previous policy of suppressing counter-revolution subsided. Against this backdrop, Communist Party leaders changed the repressive policies. The main outcome of this was the redistribution of powers between the Chek and Revolutionary Tribunal. The Cheka in early 1919 were denied the right to sentencing. The county Chekas were eliminated. On 6 November 1918, an amnesty to prisoners was issued, which according to Ratkovsky meant the end of the Red Terror. The result was a decrease in repression, with the executions in the RSFSR in 1919 numbering a third of those in 1918<ref>И. С. Ратьковский, p.186</ref> |

|||

Lenin himself seemed unfazed by the killings. On 12 January 1920, while addressing trade union leaders, he said: |

|||

Leading Cheka official [[Martin Latsis|Martyn Latsis]] stated that in the period 1918-July 1919 in Russia, there were 9,641 executions and 12,733 in the 1918-1920 period. W. H. Chamberlin claims “it is simply impossible to believe that the Cheka only put to death 12,733 people in all of Russia up to the end of the civil war.”<ref name="Chamberlin">pages 74-75, Chamberlin (1935).</ref> Chamberlin provides the "reasonable and probably moderate" estimate of 50,000,<ref name="Chamberlin"/> Author Robert Conquest claims that the number of executions at about 250,000, while Leggett puts the number at 140,000 and an equal number killed during armed revolts.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=9TWUAQ7Xof8C&pg=PA28&dq=kgb+cheka+executions+probably+numbered+as+many+as+250,000&ei=kPDrRvKoB5imoALvyaS5Dw&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=GSLukXFh7KRQx6oQTEkNvvlC77E page 28], Andrew and Mitrokhin, ''The Sword and the Shield'', paperback edition, Basic books, 1999.</ref><ref>page 180, Overy, ''The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia,'' W. W. Norton & Company; 1st American Ed edition, 2004.</ref> |

|||

: "We did not hesitate to shoot thousands of people, and we shall not hesitate, and we shall save the {{j|country." |

|||

<ref>pages 72 & 73, Volkogonov (1998).</ref>}} |

|||

On 14 May 1921, the [[Politburo]], chaired by Lenin, passed a motion "broadening the rights of the [Cheka] in relation to the use of the [death penalty]."<ref>page 238, Volkogonov (1994).</ref> |

|||

==Atrocities== |

==Atrocities== |

||

{{More footnotes|section|date=February 2011}}Claims were made by the Soviet state's opponents among the White regimes such as Denikin's Commission to Investigate Bolshevik Atrocities as well as political opponents like S. Melgunov about lurid tortures committed by Soviet forces.<ref>Vladimir N. Brovkin ''Dear comrades: Menshevik reports on the Bolshevik revolution and the civil war''.Hoover Press, 1991. p.20</ref> At the head of the Commission was a member of the anti-Soviet Kadet Party G.A. Meyngard. The tasks of this commission was to publicize the alleged crimes committed by the Soviet forces, mainly intended for a Russian emigre audience.<ref>А. Литвин. Красный и белый террор 1918—1922.Ексмо. 2004</ref> |

|||

{{More footnotes|section|date=February 2011}} |

|||

The Cheka is reported to have practiced [[torture]]. Depending on Cheka committees in various cities, the methods included:<ref name=Linc/> being skinned alive, scalped, "crowned" with barbed wire, impaled, crucified, hanged, stoned to death, tied to planks and pushed slowly into furnaces or tanks of boiling water,<ref name=Linc/> or rolled around naked in internally nail-studded barrels. Chekists reportedly poured water on naked prisoners in the winter-bound streets until they became living ice statues. Others reportedly beheaded their victims by twisting their necks until their heads could be torn off. The [[Chinese in Russian Revolution|Chinese Cheka detachments]] stationed in [[Kiev]] reportedly would attach an iron tube to the torso of a bound victim and insert a rat in the tube closed off with wire netting, while the tube was held over a flame until the rat began gnawing through the victim's guts in an effort to escape.<ref name=Linc/> [[Anton Denikin]]'s investigation discovered corpses whose lungs, throats, and mouths had been packed with earth.<ref name="Linc">[http://books.google.com/books?id=R6HAJIJhNp4C&pg=PA383&dq=red+victory+cheka+torture+beatings&ei=JPDrRvHBDY3goALEseCxDw&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=Q2uKWqXLBGbGzwKVQYfnIR-LWaQ#PPA383,M1 pages 383-385], Lincoln (1999).</ref><ref>pages 177-179, Melg(o)unov (1925).</ref><ref>page 646, Figes (1996).</ref> |

|||

Women and children were also victims of Cheka terror. Women would sometimes be tortured and raped before being shot. Children between the ages of 8 and 13 were imprisoned and occasionally executed.<ref>page 198, Leggett (1986).</ref> |

|||

All of these atrocities were published on numerous occasions in [[Pravda]] and [[Izvestiya]]: January 26, 1919 Izvestiya #18 articale ''Is it really a medieval imprisonment?'' («Неужели средневековый застенок?»); February 22, 1919 Pravda #12 publishes details of the [[Vladimir]] Cheka's tortures, September 21, 1922 ''Socialist Herald'' publishes details of series of tortures conducted by the [[Stavropol]] Cheka (hot basement, cold basement, scull measuring etc.). |

|||

The Chekists were also supplemented by the militarized Units of Special Purpose (the Party's Spetsnaz or {{lang-ru|ЧОН}}). |

|||

Cheka was actively and openly utilizing kidnapping methods.<ref>[http://mozohin.ru/article/a-10.html History of governmental bodies of Cheka] {{ru icon}}</ref><ref>В. П. Данилов. «Советская деревня глазами ВЧК-ОГПУ-НКВД», 1918—1922, М., 1998. // РГВА (Российский Государственный Военно-исторический Архив), 33987/3/32.</ref> With kidnapping methods Cheka was able to extinguish numerous cases of discontent especially among the rural population. Among the notorious ones was the [[Tambov rebellion]]. |

|||

The Cheka was alleged by the Denikin "Commission to Investigate Bolshevik Atrocities" and the publications of anti-Soviet political emigres such as S. Melgunov to have practiced [[torture]]. They claimed that Victims were reportedly crucified, stoned to death, and other measures. They claimed that the Cheka personnel poured water on naked prisoners in the streets during winter until they became living ice statues, as well as beheadings. Others reportedly beheaded their victims by twisting their necks until their heads could be torn off.<ref>pages 177-179, Melg(o)unov (1925).</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=R6HAJIJhNp4C&pg=PA383&dq=red+victory+cheka+torture+beatings&ei=JPDrRvHBDY3goALEseCxDw&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=Q2uKWqXLBGbGzwKVQYfnIR-LWaQ#PPA383,M1 pages 383-385], Lincoln (1999).</ref><ref>page 646, Figes (1996).</ref> The same sources claimed that Women and children were also victims of repression: women allegedly tortured and raped before being shot and that Children between the ages of 8 and 13 were imprisoned and occasionally executed.<ref>page 198, Leggett (1986).</ref> |

|||

Villages were bombarded to complete annihilation like in the case of Tretyaki, Novokhopersk uyezd, [[Voronezh Governorate]]. {{citation needed|date=December 2010}} |

|||

The results of the Commission's work was met with controversy. Orenburg University professor L. Futoryansky argues that "the nature of these so-called documents is questionable" according to modern standards and are not suitable for a place in a scientific publication. Futoryansky notes that the commission engaged in exaggerations and instructed witnesses to emphasize negative aspects of the Soviet state and the Cheka. Futoryansky notes that most of the documents do not have signatures, names, dates, and locations, and that "Allegations were made of V.I. Lenin's hatred for Cossacks, but we cannot find anything about this...All of this is extremely unreasonable." <ref>http://www.orenport.ru/docs/82/futor/index.html</ref> |

|||

As a result of this relentless violence more than a few Chekists ended up with psychopathic disorders, which [[Nikolai Bukharin]] said were "an occupational hazard of the Chekist profession." Many hardened themselves to the executions by heavy drinking and drug use. Some developed a gangster-like slang for the verb to kill in an attempt to distance themselves from the killings, such as 'shooting partridges', of 'sealing' a victim, or giving him a ''natsokal'' (onomatopoeia of the trigger action).<ref>page 647, Figes (1996).</ref> |

|||

Another skeptical historian, Y. Semyonov, wrote that ''"As for the material created by the Denikin Commission to Investigate the Crimes of the Bolsheviks, this institution was least interested in the truth. Its purpose was anti-Bolshevik propaganda. The White Guard propagandists were so overdone with the exposure of Bolshevik atrocities that when the falsity of much of what they said became clear, western public opinion was inclined not to believe bad things about the Bolsheviks."'' In his preface to his "Red Terror in Russia", S. Melgunov stated that he was unable to verify the authenticity of the sources he cited. In his essay "Defeated", G. Y. Villiam in the chapter "Osvag [Denikin Commission]" wrote that this institution's purpose was to slander the Soviets and the Cheka.<ref>http://scepsis.ru/library/id_423.html</ref> |

|||

On November 30, 1992, by the initiative of the [[President of the Russian Federation]] the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation recognized the Red Terror as unlawful, which in turn led to suspension of the Communist Party of the RSFSR.{{citation needed|date=December 2010}} |

|||

==Regional Chekas== |

==Regional Chekas== |

||

Revision as of 20:05, 27 October 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

| [Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | |

VCheKa emblem | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1917 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Dissolved | 1922 (reorganized) |

| Superseding agency | |

| Type | Secret police |

| Headquarters | 2 Gorokhovaya street, Petrograd Lubyanka Square, Moscow |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent agency | Council of the People's Commissars |

Cheka (ЧК - чрезвыча́йная коми́ссия chrezvychaynaya komissiya, Extraordinary Commission, Russian pronunciation: [tɕɪˈka]) was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created on December 20, 1917, after a decree issued by Vladimir Lenin, and was subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky.[1] By late 1918, hundreds of Cheka committees had been created in various cities, at multiple levels including: oblast, guberniya ("Gubcheks"), raion, uyezd, and volost Chekas, with Raion and Volost Extraordinary Commissioners. Many thousands of dissidents, deserters, or other people were arrested, tortured or executed by various Cheka groups.[2] After 1922, Cheka groups underwent a series of reorganizations, with the NKVD, into bodies whose members continued to be referred to as "Chekisty" (Chekists) into the late 1980s.[3] With Vladimir Putin's rise to power, the reference to the FSB members as "Chekists" arose, particularly by Putin's political opponents, often with negative connotations.

From its founding, the Cheka was an important military and security arm of the Bolshevik communist government. In 1921 the Troops for the Internal Defense of the Republic (a branch of the Cheka) numbered 200,000. These troops policed labor camps; ran the Gulag system; conducted requisitions of food; subjected political opponents to torture and summary execution; and put down rebellions and riots by workers or peasants, and mutinies in the desertion-plagued Red Army.[4]

Name

The name of the agency was originally "The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage"[1][3] (Russian: Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия по борьбе с контрреволюцией и саботажем; Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya po bor'bye s kontrrevolyutsiyei i sabotazhem), but was often shortened to "Cheka" or "VCheka". In 1918 its name was changed, becoming "All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution, Profiteering and Corruption".

A member of Cheka was called a "chekist". Also, the term "chekist" often referred to Soviet secret police throughout the Soviet period, despite official name changes over time. In The Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn recalls that zeks in the labor camps used "old 'Chekist'" as "a mark of special esteem" for particularly experienced camp administrators.[5] The term is still found in use in Russia today (for example, President Vladimir Putin has been referred to in the Russian media as a "chekist" due to his career in the KGB[6]).

The Chekists commonly dressed in black leather, including long flowing coats, reportedly after being issued such distinctive coats early in their existence.[7][8] Western communists adopted this clothing fashion.

History

Creation

In the first month and half after the October Revolution (1917), the duty of "extinguishing the resistance of exploiters" was assigned to the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee (or VRK). It represented a temporary body working under directives of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) and Central Committee of RDSRP(b). The VRK created new bodies of government,[clarification needed] organized food delivery to cities and the Army, requisitioned products from bourgeoisie, and sent its emissaries and agitators into provinces. One of its most important functions was the security of revolutionary order, and the fight against counterrevolutionary activity (see: Anti-Soviet agitation).

On December 1, 1917, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK or TsIK)[9] reviewed a proposed reorganization of the VRK, and possible replacement of it. On December 5, the Petrograd VRK published an announcement of dissolution and transfer the functions to the department of TsIK to the fight against "counterrevolutionaries".[10] On December 6, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) strategized how to persuade government workers to strike across Russia. They decided that a special commission was needed to implement the "most energetically revolutionary" measures. Felix Dzerzhinsky (the Iron Felix) was appointed as Director and invited the participation of the following individuals: V. K. Averin, V. N. Vasilevsky, D. G. Yevseyev, N. A. Zhydelev, I. K. Ksenofontov, G. K. Ordjonikidze, Ya. Kh. Peters, K. A. Peterson, V. A. Trifonov.

On December 7, 1917, all invited except Zhydelev and Vasilevsky gathered in the Smolny Institute to discuss the competence and structure of the commission to combat counterrevolution and sabotage. The obligations of the commission were:

- "to liquidate to the root all of the counterrevolutionary and sabotage activities and all attempts to them in all of Russia, to hand over counter-revolutionaries and saboteurs to the revolutionary tribunals, develop measures to combat them and relentlessly apply them in real world applications. The commission should only conduct a preliminary investigation.[clarification needed]"

The commission should also observe the press and counterrevolutionary parties, sabotaging officials and other criminals. It was decided to create three sections: informational, organizational, and a unit to combat counter-revolution and sabotage. Upon the end of the meeting, Dzerzhinsky reported to the Sovnarkom with the requested information. The commission was allowed to apply such measures of repression as 'confiscation, deprivation of ration cards, publication of lists of enemies of the people etc.'".[10] That day, Sovnarkom officially confirmed the creation of VCheKa. The commission was created not under the VTsIK as was previously anticipated, but rather under the Council of the People's Commissars.[11]

On December 8, 1917, some of the original members of the VCheka were replaced. Averin, Ordzhonikidze, and Trifonov were replaced by V. V. Fomin, S. E. Shchukin, Ilyin, and Chernov.[11] On the meeting of December 8, the presidium of VChK was elected of five members, and chaired by Dzerzhinsky. The issue of "speculation" [ambiguous] was raised at the same meeting, which was assigned to Peters to address and report with results to one of the next meetings of the commission. A circular, published on December 28 [O.S. December 15] 1917, gave the address of VCheka's first headquarters as "Petrograd, Gorokhovaya 2, 4th floor".[11] On December 11, Fomin was ordered to organize a section to suppress "speculation." And in the same day, VCheKa offered Shchukin to conduct arrests of counterfeiters.

In January 1918, a subsection of the anti-counterrevolutionary effort was created to police bank officials. The structure of VCheKa was changing repeatedly. By March 1918, when the organization came to Moscow, it contained the following sections: against counterrevolution, speculation, non-residents, and information gathering. By the end of 1918-1919, some units had been created: secretly operative, investigatory, of transportation, military (special), operative, and instructional. By 1921, it changed once again, forming the following sections: directory of affairs, administrative-organizational, secretly operative, economical, and foreign affairs.

First months

In the first months of its existence, VCheKa consisted of only 40 officials. It commanded a team of soldiers, the Sveaborgesky regiment, as well as a group of Red Guardsmen. On January 14, 1918, Sovnarkom ordered Dzerzhinsky to organize teams of "energetic and ideological" sailors to combat speculation. By the spring of 1918, the commission had several teams. In addition to the Sveaborge team, it had an intelligence team, a team of sailors, and a strike team. Through the winter of 1917-1918, all the activities of VCheKa were centralized mainly in the city of Petrograd. It was one of the several other commissions in the country that fought against counterrevolution, speculation, banditry, and other activities perceived as crimes. Other organizations included: the Bureau of Military Commissars, and an Army-Navy investigatory commission to attack the counterrevolutionary element in the Red Army, plus the Central Requisite and Unloading Commission to fight speculation. The investigation of counterrevolutionary or major criminal offenses was conducting by the Investigatory Commission of Revtribunal. The functions of VCheKa were closely intertwined with the Commission of V. D. Bonch-Bruyevich, which beside the fight against wine pogroms was engaged in the investigation of most major political offenses (see: Bonch-Bruyevich Commission).

All results of its activities, VCheKa had either to transfer to the Investigatory Commission of Revtribunal or to dismiss a case. The control of the commission's activity was provided by the People's Commissariat for Justice (Narkomjust, at that time headed by Isidor Steinberg) and Internal Affairs (NKVD, at that time headed by Hryhoriy Petrovsky). Although the VCheKa was officially an independent organization from the NKVD, its main members such as Dzerzhinsky, Latsis, Unszlicht, and Uritsky (all main chekists), since November 1917 composed the collegiate of NKVD headed by Petrovsky. In November 1918, Petrovsky was appointed as the head of the All-Ukrainian Central Military Revolutionary Committee during VCheKa's expansion to provinces and front-lines. At the time of political competition between Bolsheviks and SRs (January 1918), Left SRs attempted to curb the rights of VCheKa and establish through the Narkomiust its control over its work. Having failed in attempts to subordinate the VCheKa to Narkomiust, the Left SRs were to seek control of the Extraordinary Commission in a different way. They requested that the Central Committee of the party was granted the right to directly enter their representatives into the VCheKa. Sovnarkom recognized the desirability of including five representatives of the Left Socialist-Revolutionary faction of VTsIK. Left SRs were granted the post of a companion (deputy) chairman of VCheKa. However, Sovnarkom, in which the majority belonged to the representatives of RSDLP(b) retained the right to approve members of the collegium of the VCheKa.

Originally, the members of the Cheka were exclusively Bolshevik; however, in January 1918, the Left SRs also joined the organization[12] The Left SRs were expelled or arrested later in 1918, following the attempted assassination of Lenin by an SR, Fanni Kaplan.

Consolidation of VCheKa and National Establishment

By the end of January 1918, the Investigatory Commission of Petrograd Soviet (probably same as of Revtribunal) petitioned Sovnarkom to delineate the role of detection and judicial-investigatory organs. It offered to leave, for the VCheKa and the Commission of Bonch-Bruyevich, only the functions of detection and suppression, while investigative functions entirely transferred to it. The Investigatory Commission prevailed. On January 31, 1918, Sovnarkom ordered to relieve VCheKa of the investigative functions, leaving for the commission only the functions of detection, suppression, and prevention of so-called crimes. At the meeting of the Council of People's Commissars on January 31, 1918, a merger of VCheKa and the Commission of Bonch-Bruyevich was proposed. The existence of both commissions, VCheKa of Sovnarkom and the Commission of Bonch-Bruyevich of VTsIK, with almost the same functions and equal rights, became impractical. A decision followed two weeks later.[13]

On February 23, 1918, VCheKa sent a radio telegram to all Soviets with a petition to immediately organize emergency commissions to combat counter-revolution, sabotage and speculation, if such commissions had not been yet organized. February 1918 saw the creation of local Extraordinary Commissions. One of the first founded was the Moscow Cheka. Sections and commissariats to combat counterrevolution were established in other cities. The Extraordinary Commissions arose, usually in the areas during the moments of the greatest aggravation of political situation. On February 25, 1918, as the counterrevolutionary organization Union of Front-liners was making advances, the executive committee of the Saratov Soviet formed a counter-revolutionary section. On March 7, 1918, because of the move from Petrograd to Moscow, the Petrograd Cheka was created. On March 9, a section for combating counterrevolution was created under the Omsk Soviet. Extraordinary commissions were also created in Penza, Perm, Novgorod, Cherepovets, Rostov, Taganrog. On March 18, VCheKa adopted a resolution, The Work of VCheKa on the All-Russian Scale, foreseeing the formation everywhere of Extraordinary Commissions after the same model, and sent a letter that called for the widespread establishment of the Cheka in combating counterrevolution, speculation, and sabotage. Establishment of provincial Extraordinary Commissions was largely completed by August 1918. In the Soviet Republic, there were 38 gubernatorial Chekas (Gubcheks) by this time.

On June 12, 1918, the All-Russian Conference of Cheka adopted the Basic Provisions on the Organization of Extraordinary Commissions. They set out to form Extraordinary Commissions not only at Oblast and Guberniya levels, but also at the large Uyezd Soviets. In August 1918, in the Soviet Republic had accounted for some 75 Uyezd-level Extraordinary Commissions. By the end of the year, 365 Uyezd-level Chekas were established. In 1918, the All-Russia Extraordinary Commission and the Soviets managed to establish a local Cheka apparatus. It included Oblast, Guberniya, Raion, Uyezd, and Volost Chekas, with Raion and Volost Extraordinary Commissioners. In addition, border security Chekas were included in the system of local Cheka bodies.

In the autumn of 1918, as consolidation of the political situation of the republic continued, a move toward elimination of Uyezd-, Raion-, and Volost-level Chekas, as well as the institution of Extraordinary Commissions was considered. On January 20, 1919, VTsIK adopted a resolution prepared by VCheKa, On the abolition of Uyezd Extraordinary Commissions. On January 16 the presidium of VCheKa approved the draft on the establishment of the Politburo at Uyezd militsiya. This decision was approved by the Conference of the Extraordinary Commission IV, held in early February 1920.

Other types of Cheka

On August 3, a VCheKa section for combating counterrevolution, speculation and sabotage on railways was created. On August 7, 1918 Sovnarkom adopted a decree on the organization of the railway section at VCheKa. Combating counterrevolution, speculation, and malfeasance on railroads was passed under the jurisdiction of the railway section of VCheKa and local Cheka. In August 1918, railway sections were formed under the Gubcheks. Formally, they were part of the non-resident sections, but in fact constituted a separate division, largely autonomous in their activities. The gubernatorial and oblast-type Chekas retained in relationship to the transportation sections only control and investigative functions.

The beginning of a systematic work of organs of VCheKa in RKKA refers to July 1918, the period of extreme tension of the civil war and class struggle in the country. On July 16, 1918, the Council of People's Commissars formed the Extraordinary Commission for combating counterrevolution at the Czechoslovak (Eastern) Front, led by M. I. Latsis. In the fall of 1918, Extraordinary Commissions to combat counterrevolution on the Southern (Ukraine) Front were formed. In late November, the Second All-Russian Conference of the Extraordinary Commissions accepted a decision after the report of I. N. Polukarov to establish at all frontlines and army sections of the Cheka and granted them the right to appoint their commissioners in military units. On December 9, 1918, the collegiate (or presidium) of VCheKa had decided to form a military section, headed by M. S. Kedrov, to combat counterrevolution in the Army. In early 1919, the military control and the military section of VCheKa were merged into one body, the Special Section of the Republic. Kedrov was appointed as head. On January 1, he issued an order to establish the Special Section. The order instructed agencies everywhere to unite the Military control and the military sections of Chekas and to form special sections of frontlines, armies, military districts, and guberniyas.

In November 1920 the Soviet of Labor and Defense created a Special Section of VCheKa for the security of the state border.

On February 6, 1922, after the Ninth All-Russian Soviet Congress, the Cheka was dissolved by VTsIK, "with expressions of gratitude for heroic work." It was replaced by the State Political Administration or GPU, a section of the NKVD of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR).

Operations

Suppression of political opposition

Initially formed to fight against counter-revolutionaries and saboteurs, as well as financial speculators, Cheka had its own classifications. Those counter-revolutionaries fell under these categories:

- any civil or military servicemen suspected of working for Imperial Russia;

- families of officers-volunteers (including children);

- all clergy;

- workers and peasants who were under suspicion of not supporting the Soviet government;

- any other person whose private property was valued at over 10,000 rubles.

As its name implied, the Extraordinary Commission had virtually unlimited powers and could interpret them in any way it wished. No standard procedures were ever set up, except that the Commission was supposed to send the arrested to the Military-Revolutionary tribunals if outside of a war zone. This left an opportunity for a wide range of interpretations, as the whole country was in total chaos. At the direction of Lenin, the Cheka performed mass arrests, imprisonments, and executions of "enemies of the people". In this, the Cheka said that they targeted "class enemies" such as the bourgeoisie, and members of the clergy; the first organized mass repression began against the libertarians and socialists of Petrograd in April 1918. Over the next few months, 800 were arrested and shot without trial.

However, within a month, the Cheka had extended its repression to all political opponents of the communist government, including anarchists and others on the left. On April 11/12, 1918, some 26 anarchist political centres in Moscow were attacked. There 40 anarchists were killed by Cheka forces, and about 500 were arrested and jailed after a pitched battle took place between the two groups. (P. Avrich. G. Maximoff) In response to the anarchists' resistance, the Cheka orchestrated a massive retaliatory campaign of repression, executions, and arrests against all opponents of the Bolshevik government, in what came to be known as "Red Terror". The Red Terror, implemented by Dzerzhinsky on September 5, 1918, was vividly described by the Red Army journal Krasnaya Gazeta:

- "Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands, let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky … let there be floods of blood of the bourgeoisie – more blood, as much as Template:J

An early Bolshevik, Victor Serge described in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary:

Since the first massacres of Red prisoners by the Whites, the murders of Volodarsky and Uritsky and the attempt against Lenin (in the summer of 1918), the custom of arresting and, often, executing hostages had become generalized and legal. Already the Cheka, which made mass arrests of suspects, was tending to settle their fate independently, under formal control of the Party, but in reality without anybody's knowledge. The Party endeavoured to head it with incorruptible men like the former convict Dzerzhinsky, a sincere idealist, ruthless but chivalrous, with the emaciated profile of an Inquisitor: tall forehead, bony nose, untidy goatee, and an expression of weariness and austerity. But the Party had few men of this stamp and many Chekas. I believe that the formation of the Chekas was one of the gravest and most impermissible errors that the Bolshevik leaders committed in 1918 when plots, blockades, and interventions made them lose their heads. All evidence indicates that revolutionary tribunals, functioning in the light of day and admitting the right of defense, would have attained the same efficiency with far less abuse and depravity. Was it necessary to revert to the procedures of the Inquisition?"

The Cheka was also used against the armed anarchist Black Army of Nestor Makhno in the Ukraine. After the Black Army had served its purpose in aiding the Red Army to stop the Whites under Denikin, the Soviet communist government decided to eliminate the anarchist forces. In May 1919, two Cheka agents sent to assassinate Makhno were caught and executed.[14]

Many victims of Cheka repression were 'bourgeois hostages' rounded up and held in readiness for summary execution in reprisal for any alleged counter-revolutionary act. Lenin's dictum was: that it was better to arrest 100 innocent people rather than to risk one enemy going free. That ensured that wholesale, indiscriminate arrests became an integral part of the system.[15]

It was during the Red Terror that the Cheka, hoping to avoid the bloody aftermath of having half-dead victims writhing on the floor, developed a technique for execution known later by the German words "Nackenschuss" or "Genickschuss", a shot to the nape of the neck, which caused minimal blood loss and instant death. The victim's head was bent forward, and the executioner fired slightly downward at point blank range. This had become the standard method used later by the NKVD to liquidate Joseph Stalin's purge victims and others.[16]

Persecution of deserters

It is believed that there were more than three million deserters from the Red Army in 1919 and 1920. Approximately 500,000 deserters were arrested in 1919 and close to 800,000 in 1920, by troops of the 'Special Punitive Department' of the Cheka, created to punish desertions.[4][17] These troops were used to forcibly repatriate deserters, taking and shooting hostages to force compliance or to set an example. Throughout the course of the civil war, several thousand deserters were shot - a number comparable to that of belligerents during World War I.

In September 1918, according to The Black Book of Communism, in only twelve provinces of Russia, 48,735 deserters and 7,325 "bandits" were arrested, 1,826 were killed and 2,230 were executed. The exact identity of these individuals is confused by the fact that the Soviet Bolshevik government used the term 'bandit' to cover ordinary criminals as well as armed and unarmed political opponents, such as the anarchists.

Conflicts

The Civil War intensified due to the Czechoslovak invasion May 1918 that was supported by the Entente powers,.[18] Massive White Terror against the Soviet forces intensified.[19] The total number of victims of the White Terror in Central Russia at the hands of the Czechoslovaks and the SR-led Komuch regime amounted to more than 5000 people killed in the summer and autumn of 1918.[20] After the White Cossacks led by Krasnov seized control of the Don Province, more than 40,000 people were killed by Krasnov's regime.[21] In the Samara region on May 5, 1918, Dutov's Cossack forces killed 675 people by execution and burying the victims alive.[22] In the autumn of 1918, General Pokrovsky's forces killed 2500 people in the town of Maikop, while Ataman Annenkov's forces shot more than 1500 peasants in Slavgorod region.[23] The intensification in the summer of 1918 of massive and individual White Terror inevitably led to the revision of punitive-repressive policies of the Soviet government to an increase in repression. This policy more easily asserted itself with the more frequent reports of White Terror.[24]

In addition to White Terror, individual terrorism against the Soviet forces significantly increased as 1918 progressed. In the summer of 1918 in Petrograd, Socialist-Revolutionary cells organized plots of assassinations against leading Soviet officials Volodarsky, Zinoviev, and Uritsky, as well as Lenin, Trotsky, and other officials of the Soviet state. The situation in Petrograd after the assassination of Soviet official Volodarsky showed the willingness of the population for mass repression, as seen in the slogans of banners during his funeral. In Petrograd on June 22, a Menshevik member Vasiliev was killed, motivated by revenge over the death of Volodarsky. Individual terror against the Soviet government killed 339 people. The end of August 1918 marked a new surge of individual terrorism directed against the Soviet state.[25]

St Petersburg University Professor studies the subject in his book The Red Terror in Russia in 1918[26]

During the Red Terror that began in early September 1918 and ended particularly after the issuing of an amnesty to prisoners on 7 November 1918, executions amounted to amounted to 8000 people. 2000 executions occurred from August 30 to 5 September 1918, and another 3000 during the remaining days of September. 3000 more were executed during October–November 1918. There were several stages of the Red Terror during the autumn of 1918. The first stage includes the period from 30 August 1918 to 5 September 1918, beginning with the attacks on Lenin and Uritsky and ending with the publication of the Red Terror decree. During this uncontrolled wave of repression, there were more than 3 thousand executions, especially in provincial towns and the frontier provinces. More organized repression took place during the remaining days of September. The total number of victims of the policy of Red Terror in this period was up to 2 thousand.[27]

Starting in October 1918, Red Terror policy experienced a crisis. With victories at the front and the growth of the revolutionary movement in Europe, the need for the previous policy of suppressing counter-revolution subsided. Against this backdrop, Communist Party leaders changed the repressive policies. The main outcome of this was the redistribution of powers between the Chek and Revolutionary Tribunal. The Cheka in early 1919 were denied the right to sentencing. The county Chekas were eliminated. On 6 November 1918, an amnesty to prisoners was issued, which according to Ratkovsky meant the end of the Red Terror. The result was a decrease in repression, with the executions in the RSFSR in 1919 numbering a third of those in 1918[28]

Leading Cheka official Martyn Latsis stated that in the period 1918-July 1919 in Russia, there were 9,641 executions and 12,733 in the 1918-1920 period. W. H. Chamberlin claims “it is simply impossible to believe that the Cheka only put to death 12,733 people in all of Russia up to the end of the civil war.”[29] Chamberlin provides the "reasonable and probably moderate" estimate of 50,000,[29] Author Robert Conquest claims that the number of executions at about 250,000, while Leggett puts the number at 140,000 and an equal number killed during armed revolts.[30][31]

Atrocities

This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

Claims were made by the Soviet state's opponents among the White regimes such as Denikin's Commission to Investigate Bolshevik Atrocities as well as political opponents like S. Melgunov about lurid tortures committed by Soviet forces.[32] At the head of the Commission was a member of the anti-Soviet Kadet Party G.A. Meyngard. The tasks of this commission was to publicize the alleged crimes committed by the Soviet forces, mainly intended for a Russian emigre audience.[33]

The Cheka was alleged by the Denikin "Commission to Investigate Bolshevik Atrocities" and the publications of anti-Soviet political emigres such as S. Melgunov to have practiced torture. They claimed that Victims were reportedly crucified, stoned to death, and other measures. They claimed that the Cheka personnel poured water on naked prisoners in the streets during winter until they became living ice statues, as well as beheadings. Others reportedly beheaded their victims by twisting their necks until their heads could be torn off.[34][35][36] The same sources claimed that Women and children were also victims of repression: women allegedly tortured and raped before being shot and that Children between the ages of 8 and 13 were imprisoned and occasionally executed.[37]

The results of the Commission's work was met with controversy. Orenburg University professor L. Futoryansky argues that "the nature of these so-called documents is questionable" according to modern standards and are not suitable for a place in a scientific publication. Futoryansky notes that the commission engaged in exaggerations and instructed witnesses to emphasize negative aspects of the Soviet state and the Cheka. Futoryansky notes that most of the documents do not have signatures, names, dates, and locations, and that "Allegations were made of V.I. Lenin's hatred for Cossacks, but we cannot find anything about this...All of this is extremely unreasonable." [38]

Another skeptical historian, Y. Semyonov, wrote that "As for the material created by the Denikin Commission to Investigate the Crimes of the Bolsheviks, this institution was least interested in the truth. Its purpose was anti-Bolshevik propaganda. The White Guard propagandists were so overdone with the exposure of Bolshevik atrocities that when the falsity of much of what they said became clear, western public opinion was inclined not to believe bad things about the Bolsheviks." In his preface to his "Red Terror in Russia", S. Melgunov stated that he was unable to verify the authenticity of the sources he cited. In his essay "Defeated", G. Y. Villiam in the chapter "Osvag [Denikin Commission]" wrote that this institution's purpose was to slander the Soviets and the Cheka.[39]

Regional Chekas

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

Cheka departments were organized not only in big cities and guberniya seats, but also in each uyezd, at any front-lines and military formations. Nothing is known on what resources they were created. Many who were hired to head those departments were so-called "nestlings of Kerensky" (Russian: птенцы Керенского), the former convicts (political and criminal) that released by the Kerensky amnesty.

- Moscow Cheka (1918–1919)

- Chairman - Felix Dzerzhynsky, Deputy - Yakov Peters (initially heading the Petrograd Department), other members - Shklovsky, Kneyfis, Tseystin, Razmirovich, Kronberg, Khaikina, Karlson, Shauman, Lentovich, Rivkin, Antonov, Delafabr, Tsytkin, Yelena Rozmirovich (wife of Krylenko), G.Sverdlov, Bizensky, Yakov Blumkin, Aleksandrovich, Fines, Zaks, Yakov Goldin, Galpershtein, Kniggisen, Martin Latsis (later transferred to Kyiv), Deybol, Seyzan, Deybkin, Libert (chief of jail), Fogel, Zakis, Shillenkus, Yanson.

- Petrograd Cheka (1918–1919)

- Chairman - Meinkman, Moisei Uritsky (replaced Peters after his transfer), Giller, Kozlovsky, Model, Rozmirovich, I.Diesporov, Iselevich, Krassikov, Bukhan, Merbis, Paykis, Anvelt.

- Kharkov Cheka

- Comrade Eduard, Stepan Saenko, Mykola Khvylovy (Bohodukhiv uyezd).

- Kiev Cheka

- Chairman - Martin Latsis, other members - Avdokhin, Comrade Vera, Rosa Shvarts.

- Odessa Cheka

- Deych, Vikhman, Timofey, Vera (Dora) Grebenshchikova, Aleksandra (aged 17).

- Simferopol Cheka

- Ashykin.

Popular culture

- The Cheka were popular staples in Soviet film and literature. This was partly due to a romanticization of the organisation in the post-Stalin period, and also because they provided a useful action/detection template. Films featuring the Cheka include Ostern's Miles of Fire, Nikita Mikhalkov's At Home among Strangers, the miniseries The Adjutant of His Excellency, and also Dead Season (starring Donatas Banionis), and the 1992 Russian drama film The Chekist.[40]

- In Spain, during the Spanish Civil War, the detention and torture centers operated by the Communists were named "checas" after the Soviet organization.[41] Alfonso Laurencic was their promoter, ideologist and builder.[42]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b The Impact of Stalin's Leadership in the USSR,1924-1941. Nelson Thornes. 2008. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7487-8267-3.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lincwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Library of Congress / Federal Research Division / Country Studies / Area Handbook Series/ Soviet Union / Glossary". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ a b Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Alexander (1974). The Gulag Archipelago. Vol. II. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. pp. 537–38. ISBN 0-06-092103-X.

An old Chekist! Who has not heard these words, drawled with emphasis, as a mark of special esteem? If the zeks wish to distinguish a camp keeper from those who are inexperienced, inclined to fuss, and do not have a bulldog grip, they say: 'And the chief there is an o-o-old Chekist!' ... 'An old Chekist' — what that means at the least is that he was well-regarded under Yagoda, Yezhov and Beria. He was useful to them all.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "A Stalin Slip and Putin Trick | Opinion". The Moscow Times. 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ Mikhail Khvostov, The Russian Civil War (1): The Red Army

- ^ Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK or TsIK) is not to be confused with the Central Committee of RDSRP(b)

- ^ a b Mozokhin, O.B. out of history of activities of VChK, OGPU, NKVD, MGB. FSB archives.Template:Ru icon

- ^ a b c "Partial protocol of the 21st session of the Council of the People's Commissars". Memory.irk.ru. 1998-12-26. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ Schapiro (1984).

- ^ Izvestiya. February 28, 1918.

- ^ Avrich, Paul, "Russian Anarchists and the Civil War", Russian Review, Volume 27, Issue 3 (July 1968), pp. 296-306.

- ^ page 643, Figes (1996).

- ^ Paul, Allen. Katyn: Stalin's Massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection. Naval Institute Press, 1996. ISBN 1-55750-670-1 pp. 111/112.

- ^ Chamberlain, William Henry, The Russian Revolution: 1917-1921, New York: Macmillan Co. (1957), p. 131

- ^ Л. С. Гапоненко (ответственный редактор) Рабочий класс в Октябрьской революции и на защите ее завоеваний 1917 - 1920 гг. Наука. 1984. p. 222

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.96

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.36

- ^ Футорянский Л. И. Казачество в огне гражданской войны в России (1918—1920 гг.). РИК ГОУ ОГУ, 2003

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.105

- ^ http://www.gumer.info/bibliotek_Buks/History/Rat/04.php

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.144

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.120

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, Красный террор и деятельность ВЧК в 1918 году. СПб.: Изд-во С.-Петерб. ун-та, 2006.

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.199

- ^ И. С. Ратьковский, p.186

- ^ a b pages 74-75, Chamberlin (1935).

- ^ page 28, Andrew and Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield, paperback edition, Basic books, 1999.

- ^ page 180, Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, W. W. Norton & Company; 1st American Ed edition, 2004.

- ^ Vladimir N. Brovkin Dear comrades: Menshevik reports on the Bolshevik revolution and the civil war.Hoover Press, 1991. p.20

- ^ А. Литвин. Красный и белый террор 1918—1922.Ексмо. 2004

- ^ pages 177-179, Melg(o)unov (1925).

- ^ pages 383-385, Lincoln (1999).

- ^ page 646, Figes (1996).

- ^ page 198, Leggett (1986).

- ^ http://www.orenport.ru/docs/82/futor/index.html

- ^ http://scepsis.ru/library/id_423.html

- ^ Chekist (1992)

- ^ International justice begins at home[dead link]

- ^ Rafael Chacón, "Por qué hice las checas de Barcelona. Laurencic ante el consejo de guerra", Editorial Solidaridad nacional, Barcelona, 1939.

References

- Andrew, Christopher M. and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999) The Sword and the Shield : The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00312-5.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1

- Carr, E. H. (1958) The Origin and Status of the Cheka. Soviet Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–11.

- Chamberlin, W. H. (1935) The Russian Revolution 1917-1921, 2 vols. London and New York. The Macmillan Company.

- Dziak, John. (1988) Chekisty: A History of the KGB. Lexington, Mass. Lexington Books.

- Figes, Orlando (1997) A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-85916-8.

- Leggett, George (1986) The Cheka: Lenin's Political Police. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 0-19-822862-7

- Lincoln, Bruce W. (1999) Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80909-5

- Melgounov, Sergey Petrovich (1925) The Red Terror in Russia. London & Toronto: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- Overy, Richard (2004) The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton & Company; 1st American edition. ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- Rummel, Rudolph Joseph (1990) Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3

- Schapiro, Leonard B. (1984) The Russian Revolutions of 1917 : The Origins of Modern Communism. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07154-6

- Volkogonov, Dmitri (1994) Lenin: A New Biography. Free Press. ISBN 0-02-933435-7

- Volkogonov, Dmitri (1998) Autopsy of an Empire: The Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime Free Press. ISBN 0-684-87112-2

External links

- The Cheka - Spartacus Schoolnet collection of primary source extracts relating to the Cheka

- Development of the Soviet system of punitive organs Template:Ru icon