Squalene: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 633797494 by Kailas Suryawanshi (talk) |

Episcophagus (talk | contribs) →Shark squalene: Fixed two (formerly) dead links |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

== Shark squalene == |

== Shark squalene == |

||

[[File:Shark liver oil Capsule.jpg|thumbnail|right|Shark liver oil Capsule.]] |

[[File:Shark liver oil Capsule.jpg|thumbnail|right|Shark liver oil Capsule.]] |

||

Squalene is a low density compound often stored in the bodies of [[Chondrichthyes|cartilaginous fish]] such as [[shark]]s, which lack a [[swim bladder]] and must therefore reduce their body density with fats and oils. Squalene, which is stored mainly in the shark's [[liver]], is lighter than water with a specific gravity of 0.855. Recently it has become a trend for sharks to be hunted to process their livers for the purpose of making squalene health capsules. Environmental and other concerns over shark hunting have motivated its extraction from vegetable sources<ref>[[EWG]]: [http://www. |

Squalene is a low density compound often stored in the bodies of [[Chondrichthyes|cartilaginous fish]] such as [[shark]]s, which lack a [[swim bladder]] and must therefore reduce their body density with fats and oils. Squalene, which is stored mainly in the shark's [[liver]], is lighter than water with a specific gravity of 0.855. Recently it has become a trend for sharks to be hunted to process their livers for the purpose of making squalene health capsules. Environmental and other concerns over shark hunting have motivated its extraction from vegetable sources<ref>[[EWG]]: [http://www.ewg.org/enviroblog/2008/02/unilever-takes-bite-out-your-face-cream Unilever takes a bite out of your face cream]</ref> or biosynthetic processes instead.<ref> |

||

[[Amyris]]: [http://www.amyris.com/ |

[[Amyris]]: [http://www.amyris.com/News/145/Amyris-and-Soliance-Partner-to-Commercialize-Renewable-Bio-Sourced-Cosmetics]</ref> |

||

== Derivative used as a skin moisturizer in cosmetics == |

== Derivative used as a skin moisturizer in cosmetics == |

||

Revision as of 08:17, 21 November 2014

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

(6E,10E,14E,18E)-2,6,10,15,19,23-Hexamethyltetracosa-2,6,10,14,18,22-hexaene[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| 1728919 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.479 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Squalene |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C30H50 | |

| Molar mass | 410.730 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Pale yellow, translucent liquid |

| Density | 0.858 g cm-3 |

| Melting point | −5 °C (23 °F; 268 K) |

| Boiling point | 285 °C (545 °F; 558 K) |

| log P | 12.188 |

| Viscosity | 12 cP (at 20 °C) |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 110 °C (230 °F; 383 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

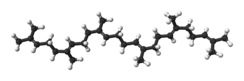

Squalene is a natural 30-carbon organic compound originally obtained for commercial purposes primarily from shark liver oil (hence its name), although plant sources (primarily vegetable oils) are now used as well, including amaranth seed, rice bran, wheat germ, and olives. It is also found in high concentrations in the stomach oil of birds in the order Procellariiformes. All plants and animals produce squalene as a biochemical intermediate, including humans.

Squalene is a hydrocarbon and a triterpene, and is a natural and vital part of the synthesis of all plant and animal sterols, including cholesterol, steroid hormones, and vitamin D in the human body.[4]

Squalene is used in cosmetics, and more recently as an immunologic adjuvant in vaccines. Squalene has been proposed to be an important part of the Mediterranean diet as it may be a chemopreventive substance that protects people from cancer.[5][6]

Role in steroid synthesis

In animals, squalene is the biochemical precursor to the whole family of steroids.[7] Oxidation (via squalene monooxygenase) of one of the terminal double bonds of squalene yields 2,3-squalene oxide, which undergoes enzyme-catalyzed cyclization to afford lanosterol, which is then elaborated into cholesterol and other steroids.

Squalene is an ancient molecule. In plants, squalene is the precursor to stigmasterol. In certain fungi, it is the precursor to ergosterol. However, blue-green algae and some bacteria do not manufacture squalene, and must acquire it from the environment if they need it.

Biosynthesis

- Two molecules of farnesyl pyrophosphate condense with reduction by NADPH to form squalene - by squalene synthase.

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

Shark squalene

Squalene is a low density compound often stored in the bodies of cartilaginous fish such as sharks, which lack a swim bladder and must therefore reduce their body density with fats and oils. Squalene, which is stored mainly in the shark's liver, is lighter than water with a specific gravity of 0.855. Recently it has become a trend for sharks to be hunted to process their livers for the purpose of making squalene health capsules. Environmental and other concerns over shark hunting have motivated its extraction from vegetable sources[8] or biosynthetic processes instead.[9]

Derivative used as a skin moisturizer in cosmetics

Squalene is one of the most common lipids produced by human skin cells.[10] It is a natural moisturizer, and occurs as a major component of nasal sebum.

Squalane is a saturated form of squalene in which the double bonds have been eliminated by hydrogenation. Squalane is less susceptible to oxidation than squalene. Squalane is thus more commonly used than squalene in personal care products, such as moisturizers.

Toxicology studies have determined that in the concentrations used in cosmetics, both squalene and squalane have low acute toxicity, and are not significant human skin irritants or sensitizers.[11]

A technology enabling the use of amaranth oil microcapsules containing squalene in textile coating was developed.[12][13]

Use as an adjuvant in vaccines

Immunologic adjuvants are substances, administered in conjunction with a vaccine, that stimulate the immune system and increase the response to the vaccine. Squalene is not itself an adjuvant, but it has been used in conjunction with surfactants in certain adjuvant formulations.[14]

An adjuvant using squalene is Novartis' proprietary adjuvant MF59, which is added to influenza vaccines to help stimulate the human body's immune response through production of CD4 memory cells. It is the first oil-in-water influenza vaccine adjuvant to be commercialized in combination with a seasonal influenza virus vaccine. It was developed in the 1990s by researchers at Ciba-Geigy and Chiron; both companies were subsequently acquired by Novartis.[15] It is present in the form of an emulsion and is added to make the vaccine more immunogenic.[14] However, the mechanism of action remains unknown. MF59 is capable of switching on a number of genes that partially overlap with those activated by other adjuvants.[16] How these changes are triggered is unclear; to date, no receptors responding to MF59 have been identified. One possibility is that MF59 affects the cell behavior by changing the lipid metabolism, namely by inducing accumulation of neutral lipids within the target cells.[17] An MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccine (Fluad, developed by Chiron, which contains about 10 mg of squalene per dose) has been approved by health agencies and used in several European countries for seasonal flu shots since 1997.[18] However, the Food and Drug Administration has not authorized the use of such adjuvants in the United States.[19] Glaxo Smith Kline used the squalene-based AS03 adjuvant in their 2009 influenza pandemic vaccine Pandemrix and Arepanrix.[20]

A 2009 meta-analysis by researchers at Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics that was published in the journal Vaccine brought together data from 64 clinical trials of influenza vaccines with the squalene-containing adjuvant MF59 and compared them to the effects of vaccines with no adjuvant. The analysis reported that the adjuvanted vaccines were associated with slightly lower risks of chronic diseases, but that neither type of vaccines altered the rate of autoimmune diseases; the authors concluded that their data "supports the good safety profile associated with MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccines and suggests there may be a clinical benefit over non-MF59-containing vaccines".[21]

Health controversy

There have been attempts to link squalene to Gulf War Syndrome mainly due to the idea that squalene might have been present in an anthrax vaccine given to some military personnel during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Studies led by Pam Asa of Tulane University found that deployed Persian Gulf War Syndrome patients are significantly more likely to have antibodies to squalene (95 percent) than asymptomatic Gulf War veterans (0 percent; p<.001).[22][23] The first of these published results concludes with the following statement: "It is important to note that our laboratory-based investigations do not establish that squalene was added as adjuvant to any vaccine used in military or other personnel who served in the Persian Gulf War era." The second publication, however, links the incidence of anti-squalene antibodies and Gulf War Syndrome to five specific lots of vaccine. Furthermore, they cite results of 1999 testing by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration which found these specific lots of vaccine to contain squalene.[24] In response to these results, a committee of the US Institute of Medicine stated that "The committee does not regard this study as providing evidence that the investigators have successfully measured antibodies to squalene", since the authors did not perform the normal scientific controls needed to show that their test was specific to anti-squalene antibodies.[25] It has also been determined that the anthrax vaccines given to those US military personnel did not use squalene as an adjuvant.[26][27][28] The vaccines were also tested for squalene, and none was detected with standard methods.[29] A much more sensitive method was then developed, which again found no squalene in 37 of the 38 lots tested. One lot contained traces of squalene, at less than ten parts per billion, which is about 30-fold less than the level found in human blood.[30] The FDA stated that this trace of squalene probably came from a fingerprint, since the oils on human skin contain enough squalene to send these extremely sensitive tests "off the chart".[31]

A later study reported that about one in ten people have squalene antibodies in their blood, regardless of whether or not they received squalene from a vaccination.[32] A later study confirmed this result, and also showed that vaccination with squalene-containing vaccines do not alter the levels of these naturally-occurring antibodies.[26] A third study showed that these naturally-occurring antibodies were no more common in Gulf war veterans than in the general population.[33]

Oil-water suspensions, including MF59, were associated with the ability to induce lupus autoantibodies in non-autoimmune mice.[34] In one study, endogenous squalene was linked to autoimmune arthritis in rats.[35] An epidemiologic analysis of safety data on MF59 seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines showed no evidence of increased risk of vaccine adverse events of potential autoimmune origin.[21]

The World Health Organization and the US Department of Defense have both published extensive reports that emphasize that squalene is a chemical naturally occurring in the human body, present even in oils of human fingerprints.[14][36] WHO goes further to explain that squalene has been present in over 22 million flu vaccines given to patients in Europe since 1997 and there have never been significant vaccine-related adverse events.[14]

Possible health benefits

It has been suspected that sharks are resistant to cancer due to high tissue levels of squalene.[37] Squalene anti-tumor activity in animal experiments[38] and epidemiological evidence based on olive oil consumption also suggest reduction of cancer risk by squalene.[39] Squalene has been shown to quench singlet oxygen.[40] Squalene had been shown to enhance the elimination of theophylline, phenobarbital, and strychnine from the bodies of rats and mice.[41]

References

- ^ CID 1105 from PubChem

- ^ Ernst, Josef; Sheldrick, William S.; Fuhrhop, Juergen H. (1976). "Crystal structure of squalene". Angewandte Chemie. 88 (24): 851. doi:10.1002/ange.19760882414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 8727

- ^ "Cholesterol Synthesis".

- ^ Smith, Theresa J (2000). "Squalene: potential chemopreventive agent". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 9 (8): 1841–8. doi:10.1517/13543784.9.8.1841. PMID 11060781.

- ^ Owen, R W; Haubner, R; Würtele, G; Hull, W E; Spiegelhalder, B; Bartsch, H (2004). "Olives and olive oil in cancer prevention". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 13 (4): 319–26. doi:10.1097/01.cej.0000130221.19480.7e. PMID 15554560.

- ^ Bloch, Konrad E. (1983). "Sterol, Structure and Membrane Functio". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 14: 47–92. doi:10.3109/10409238309102790.

- ^ EWG: Unilever takes a bite out of your face cream

- ^ Amyris: [1]

- ^ Cotterill, J.A.; W. J. CUNLIFFE; B. WILLIAMSON; L. BULUSU (October 1972). "AGE AND SEX VARIATION IN SKIN SURFACE LIPID COMPOSITION AND SEBUM EXCRETION RATE". Br. J. Dermatol. 87 (4): 333–340. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb07419.x. PMID 5077864.

- ^ "Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Squalane and Squalene". International Journal of Toxicology. 1 (2): 37–56. 1982. doi:10.3109/10915818209013146.

- ^ http://www.enviweb.cz/clanek/zdrav/96406/vyroba-textilii-s-potravinarskym-podtextem

- ^ http://www.adsaleata.com/Publicity/Mobile/ePub/lang-eng/article-67006869/asid-77/Article.aspx

- ^ a b c d Squalene-based adjuvants in vaccines, Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, World Health Organization

- ^ MF59 Adjuvant Fact Sheet, Novartis, June 2009.

- ^ Mosca, F.; Tritto, E.; Muzzi, A.; Monaci, E.; Bagnoli, F.; Iavarone, C.; O'Hagan, D.; Rappuoli, R.; De Gregorio, E. (2008). "Molecular and cellular signatures of human vaccine adjuvants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (30): 10501–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804699105.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^ Kalvodova, Lucie (2010). "Squalene-based oil-in-water emulsion adjuvants perturb metabolism of neutral lipids and enhance lipid droplet formation". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 393 (3): 350–5. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.062. PMID 20018176.

- ^ Andrew Pollack. Benefit and Doubt in Vaccine Additive, The New York Times, September 21, 2009.

- ^ Rob Stein. Swine Flu Campaign Waits on Vaccine. The Washington Post, August 23, 2009.

- ^ http://www.gsk.ca/english/docs-pdf/Arepanrix_PIL_CAPA01v01.pdf

- ^ a b Pellegrini, Michele; Nicolay, Uwe; Lindert, Kelly; Groth, Nicola; Della Cioppa, Giovanni (2009). "MF59-adjuvanted versus non-adjuvanted influenza vaccines: Integrated analysis from a large safety database". Vaccine. 27 (49): 6959–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.101. PMID 19751689.

- ^ Asa, P; Wilson, R; Garry, RF (2002). "Antibodies to Squalene in Recipients of Anthrax Vaccine". Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 73 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1006/exmp.2002.2429. PMID 12127050.

- ^ Asa, P; Cao, Y; Garry, RF (2000). "Antibodies to Squalene in Gulf War Syndrome". Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 68 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1006/exmp.1999.2295. PMID 10640454.

- ^ Committee on Government Reform Hearings for the United States House of Representatives, October 3rd and 11th, 2000. "Accountability of DoD, FDA and BioPort Officials for the Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program (AVIP)."

- ^ Sox, Harold C.; Fulco, Carolyn; Liverman, Catharyn T. (2000). Gulf War and health. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. p. 311. ISBN 0-309-07178-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Del Giudice, G.; Fragapane, E.; Bugarini, R.; Hora, M.; Henriksson, T.; Palla, E.; O'Hagan, D.; Donnelly, J.; et al. (2006). "Vaccines with the MF59 Adjuvant Do Not Stimulate Antibody Responses against Squalene". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 13 (9): 1010–3. doi:10.1128/CVI.00191-06. PMC 1563566. PMID 16960112.

- ^ Gulf War illnesses: questions about the presence of squalene antibodies in veterans can be resolved, United States General Accounting Office 1999

- ^ Jess Henig Innoculation Misinformation: Claims that the swine flu vaccine is dangerous range from overblown to false Newsweek Oct 19, 2009

- ^ Spanggord, R; Wu, B; Sun, M; Lim, P; Ellis, WY (2002). "Development and application of an analytical method for the determination of squalene in formulations of anthrax vaccine adsorbed". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 29 (1–2): 183–93. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00009-2. PMID 12062677.

- ^ Spanggord, Ronald J.; Sun, Meg; Lim, Peter; Ellis, William Y. (2006). "Enhancement of an analytical method for the determination of squalene in anthrax vaccine adsorbed formulations". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 42 (4): 494–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2006.04.009. PMID 16762524.

- ^ The Facts on Squalene FDA 2005

- ^ Matyas, G; Rao, M; Pittman, PR; Burge, R; Robbins, IE; Wassef, NM; Thivierge, B; Alving, CR (2004). "Detection of antibodies to squalene III. Naturally occurring antibodies to squalene in humans and mice". Journal of Immunological Methods. 286 (1–2): 47–67. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2003.11.002. PMID 15087221.

- ^ Phillips, Christopher J.; Matyas, Gary R.; Hansen, Christian J.; Alving, Carl R.; Smith, Tyler C.; Ryan, Margaret A.K. (2009). "Antibodies to squalene in US Navy Persian Gulf War veterans with chronic multisymptom illness". Vaccine. 27 (29): 3921–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.091. PMID 19379786.

- ^ Satoh, M; Kuroda, Y; Yoshida, H; Behney, KM; Mizutani, A; Akaogi, J; Nacionales, DC; Lorenson, TD; et al. (2003). "Induction of lupus autoantibodies by adjuvants". Journal of Autoimmunity. 21 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/S0896-8411(03)00083-0. PMID 12892730.

- ^ Carlson, Barbro C.; Jansson, Åsa M.; Larsson, Anders; Bucht, Anders; Lorentzen, Johnny C. (2000). "The Endogenous Adjuvant Squalene Can Induce a Chronic T-Cell-Mediated Arthritis in Rats". The American Journal of Pathology. 156 (6): 2057–65. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65077-8. PMC 1850095. PMID 10854227.

- ^ Asano, KG; Bayne, CK; Horsman, KM; Buchanan, MV (2002). "Chemical composition of fingerprints for gender determination". Journal of forensic sciences. 47 (4): 805–7. doi:10.1520/JFS15460J. PMID 12136987.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_inactivedate=ignored (help) - ^ Mathews J (1992). "Sharks still intrigue cancer researchers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 84 (13): 1000–1002. doi:10.1093/jnci/84.13.1000-a. PMID 1608049.

- ^ Smith TJ (2000). "Squalene: potential chemopreventive agent". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 9 (8): 1841–1848. doi:10.1517/13543784.9.8.1841. PMID 11060781.

- ^ Newmark HL (1997). "Squalene, olive oil, and cancer risk: a review and hypothesis". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 6 (12): 1101–1103. PMID 9419410.

- ^ Kohno Y, Egawa Y, Itoh S, Nagaoka S, Takahashi M, Mukai K (1995). "Kinetic study of quenching reaction of singlet oxygen and scavenging reaction of free radical by squalene in n-butanol". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1256 (1): 52–56. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(95)00005-w. PMID 7742356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kamimura H, Koga N, Oguri K, Yoshimura H (1992). "Enhanced elimination of theophylline, phenobarbital and strychnine from the bodies of rats and mice by squalane treatment". Journal of Pharmacobio-Dynamics. 15 (5): 215–221. doi:10.1248/bpb1978.15.215. PMID 1527697.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)