Blood type: Difference between revisions

HI |

m Reverted edits by 170.24.132.60 (talk) (HG) (3.1.20) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{For|the album by Soviet band Kino|Blood Type (album)}} |

|||

HI MR EBERLING |

|||

[[Image:ABO blood type.svg|thumb|right|410px|Blood type (or blood group) is determined, in part, by the ABO blood group antigens present on red blood cells.]] |

|||

Overlord Eberling |

|||

A '''blood type''' (also called a '''blood group''') is a classification of [[blood]] based on the presence and absence of [[antibodies]] and also based on the presence or absence of [[Heredity|inherited]] [[antigen]]ic substances on the surface of [[red blood cell]]s (RBCs). These antigens may be [[protein]]s, [[carbohydrate]]s, [[glycoprotein]]s, or [[glycolipid]]s, depending on the blood group system. Some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of [[Cell (biology)#Eukaryotic cells|cell]]s of various [[Tissue (biology)|tissues]]. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens can stem from one [[allele]] (or an alternative version of a gene) and collectively form a blood group system.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| last = Maton |

|||

| first = Anthea |

|||

|author2=Jean Hopkins|author3=Charles William McLaughlin|author4=Susan Johnson|author5=Maryanna Quon Warner|author6=David LaHart|author7=Jill D. Wright |

|||

| title = Human Biology and Health |

|||

| publisher = Prentice Hall |

|||

| year = 1993 |

|||

| location = Englewood Cliffs NJ |

|||

| isbn = 0-13-981176-1}}</ref> |

|||

Blood types are inherited and represent contributions from both parents. A total of 35 [[human blood group systems]] are now recognized by the [[International Society of Blood Transfusion]] (ISBT).<ref name="ISBT3.0">{{cite web |url= http://www.isbtweb.org/fileadmin/user_upload/files-2015/red%20cells/general%20intro%20WP/Table%20blood%20group%20systems%20v4.0%20141125.pdf |title= Table of blood group systems v4.0 |date= November 2014 |publisher= [[International Society of Blood Transfusion]] |accessdate = April 9, 2015 }}</ref> The two most important ones are [[ABO blood group system|ABO]] and the [[Rh blood group system|RhD antigen]]; they determine someone's blood type (A, B, AB and O, with +, − or Null denoting RhD status). |

|||

Many [[Pregnancy|pregnant]] women carry a [[fetus]] with a blood type which is different from their own, which is not a problem. What can matter is whether the baby is RhD positive or negative. Mothers who are RhD- and carry a RhD+ baby can form [[antibodies]] against fetal RBCs. Sometimes these maternal antibodies are [[Immunoglobulin G|IgG]], a small immunoglobulin, which can cross the placenta and cause [[hemolysis]] of fetal RBCs, which in turn can lead to [[hemolytic disease of the newborn]] called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness of [[Anemia|low fetal blood counts]] that ranges from mild to severe. Sometimes this is lethal for the fetus; in these cases it is called [[hydrops fetalis]].<ref name =Letsky2000>{{cite book |title =Antenatal & neonatal screening |edition = 2nd |chapter = Chapter 12: Rhesus and other haemolytic diseases |author = E.A. Letsky |author2=I. Leck|author3=J.M. Bowman |year = 2000 |publisher = Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-262826-8}}</ref> |

|||

==Blood group systems== |

|||

A complete blood type would describe a full set of 30 substances on the surface of RBCs, and an individual's blood type is one of many possible combinations of blood-group antigens.<ref name=iccbba>{{cite web |url=http://ibgrl.blood.co.uk/isbt%20pages/isbt%20terminology%20pages/table%20of%20blood%20group%20systems.htm |title=Table of blood group systems |accessdate=2008-09-12 |date=October 2008 |publisher=International Society of Blood Transfusion }}</ref> Across the 35 blood groups, over 600 different blood-group antigens have been found,<ref name="newenglandblood1"><!-- |

|||

--> {{cite web |url=http://www.newenglandblood.org/medical/rare.htm |title=American Red Cross Blood Services, New England Region, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont |accessdate=2008-07-15 |year=2001 |publisher=American Red Cross Blood Services – New England Region |quote=there are more than 600 known antigens besides A and B that characterize the proteins found on a person's red cells |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20080621091025/http://www.newenglandblood.org/medical/rare.htm |archivedate = June 21, 2008}}</ref><!-- |

|||

-->Almost always, an individual has the same blood group for life, but very rarely an individual's blood type changes through addition or suppression of an antigen in [[infection]], [[malignancy]], or [[autoimmune disease]].<ref>{{harvnb|Dean|2005|loc=[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/n/rbcantigen/ch05ABO/ The ABO blood group] "... A number of illnesses may alter a person's ABO phenotype ..."}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Stayboldt C, Rearden A, Lane TA |title=B antigen acquired by normal A1 red cells exposed to a patient's serum |journal=Transfusion |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=41–4 |year=1987 |pmid=3810822 |doi=10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27187121471.x}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Matsushita S, Imamura T, Mizuta T, Hanada M |title=Acquired B antigen and polyagglutination in a patient with gastric cancer |journal=The Japanese Journal of Surgery |volume=13 |issue=6 |pages=540–2 |date=November 1983 |pmid=6672386 |doi=10.1007/BF02469500}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kremer Hovinga I, Koopmans M, de Heer E, Bruijn J, Bajema I |title=Change in blood group in systemic lupus erythematosus |journal=Lancet |volume=369 |issue=9557 |pages=186–7; author reply 187 |year=2007 |doi= 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60099-3 |pmid= 17240276}}</ref> Another more common cause in blood type change is a [[bone marrow transplant]]. Bone-marrow transplants are performed for many [[leukemias]] and [[lymphomas]], among other diseases. If a person receives bone marrow from someone who is a different ABO type (e.g., a type A patient receives a type O bone marrow), the patient's blood type will eventually convert to the donor's type. |

|||

Some blood types are associated with inheritance of other diseases; for example, the [[Kell blood group system|Kell antigen]] is sometimes associated with [[McLeod syndrome]].<ref><!-- |

|||

-->{{cite journal |author1=Chown B. |author2=Lewis M. |author3=Kaita K. |title=A new Kell blood-group phenotype |journal=Nature |volume=180 |issue=4588 |page=711 |date=October 1957 |pmid=13477267 |doi=10.1038/180711a0}}</ref><!-- |

|||

--> Certain blood types may affect susceptibility to infections, an example being the resistance to specific [[malaria]] species seen in individuals lacking the [[Duffy antigen]].<ref><!-- |

|||

-->{{cite journal |doi=10.1056/NEJM197608052950602 |vauthors=Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH |title=The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy |journal=The New England Journal of Medicine |volume=295 |issue=6 |pages=302–4 |date=August 1976 |pmid=778616}}</ref><!-- |

|||

--> The Duffy antigen, presumably as a result of [[natural selection]], is more common in ethnic groups from areas with a high incidence of malaria.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kwiatkowski DP |title=How Malaria Has Affected the Human Genome and What Human Genetics Can Teach Us about Malaria |journal=American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=77 |issue=2 |pages=171–92 |date=August 2005 |pmid=16001361 |pmc=1224522 |doi=10.1086/432519 |quote=The different geographic distributions of α thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, ovalocytosis, and the Duffy-negative blood group are further examples of the general principle that different populations have evolved different genetic variants to protect against malaria}}</ref> |

|||

===ABO blood group system=== |

|||

[[Image:ABO blood group diagram.svg|right|thumb|350px|''ABO blood group system'': diagram showing the carbohydrate chains that determine the ABO blood group]] |

|||

{{Main|ABO blood group system}} |

|||

In human blood there are two antigens and antibodies. The two antigens are antigen A and antigen B. The two antibodies are antibody A and antibody B. The |

|||

antigens are present in the red blood cells and the antibodies in the serum. |

|||

Regarding the antigen property of the blood all human beings can be classified into 4 groups, those with antigen A (group A), those with antigen B (group B), those with both antigen A and B (group AB) and those with neither antigen (group O). The antibodies present together with the antigens are found as follows : |

|||

1. Antigen A with antibody B |

|||

2. Antigen B with antibody A |

|||

3. Antigen AB has no antibodies |

|||

4. Antigen nil (group O) with antibody A and B. |

|||

There is an agglutination reaction between similar antigen and antibody (for example, antigen A agglutinates the antibody A and antigen B agglutinates the antibody B) Thus, transfusion can be considered safe as long as the serum of the recipient does not contain antibodies for the blood cell antigens of the donor. |

|||

The ''ABO system'' is the most important blood-group system in human-blood transfusion. The associated anti-A and anti-B antibodies are usually ''[[immunoglobulin M]]'', abbreviated [[IgM]], antibodies. ABO IgM [[antibodies]] are produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, [[bacteria]], and [[virus]]es. The '''original terminology''' used by Dr. Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is A/B/C; in later publications "C" became "O".<ref name=Oor0>{{Citation | last1 = Schmidt | first1 = P | last2 = Okroi | first2 = M | title = Also sprach Landsteiner – Blood Group ‘O’ or Blood Group ‘NULL’ | journal = Infus Ther Transfus Med | volume = 28 | issue = 4 | pages = 206–8 | year = 2001 | pmid = | doi = 10.1159/000050239}}</ref> "O" is often called ''0'' (''zero'', or ''null'') in other languages. The [http://bmg.gv.at/home/EN/Home Austrian Federal Ministry of Health] claims the '''original terminology''' used by Dr. Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is 0(Zero)/A/B/AB and that in later publications "0" became "O" in most of English language countries.<ref name="Oor0"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bloddonor.dk/fileadmin/Fil_Arkiv/PDF_filer/Andre/Your_Blood__June_2006.pdf |title=Your blood – a textbook about blood and blood donation |accessdate=2008-07-15 |format=PDF |work= |page=63 |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20080626184746/http://www.bloddonor.dk/fileadmin/Fil_Arkiv/PDF_filer/Andre/Your_Blood__June_2006.pdf |archivedate = June 26, 2008}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="width:100px;"|[[Phenotype]] |

|||

! style="width:100px;"|[[Genotype]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| A || AA or AO |

|||

|- |

|||

| B || BB or BO |

|||

|- |

|||

| AB || AB |

|||

|- |

|||

| O || OO |

|||

|} |

|||

===Rh blood group system=== |

|||

{{Main|Rh blood group system}} |

|||

The Rh system (Rh meaning ''Rhesus'') is the second most significant blood-group system in human-blood transfusion with currently 50 antigens. The most significant Rh antigen is the D antigen, because it is the most likely to provoke an immune system response of the five main Rh antigens. It is common for D-negative individuals not to have any anti-D IgG or IgM antibodies, because anti-D antibodies are not usually produced by sensitization against environmental substances. However, D-negative individuals can produce [[IgG]] anti-D antibodies following a sensitizing event: possibly a fetomaternal transfusion of blood from a fetus in pregnancy or occasionally a blood transfusion with D positive [[Red blood cell|RBC]]s.<ref name="Talaro, Kathleen P. 2005 510–1">{{cite book|author=Talaro, Kathleen P.|title=Foundations in microbiology|publisher=McGraw-Hill|location=New York|year=2005|pages=510–1|isbn=0-07-111203-0 |edition=5th}}</ref> [[Rh disease]] can develop in these cases.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Moise KJ|title=Management of rhesus alloimmunization in pregnancy|journal=Obstetrics and Gynecology|volume=112|issue=1|pages=164–76|date=July 2008|pmid=18591322|doi=10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817d453c}}</ref> Rh negative blood types are much less common in Asian populations (0.3%) than they are in White populations (15%).<ref name="Rh group and its origin">{{cite web|url=http://hospital.kingnet.com.tw/activity/blood/html/a.html|title=Rh血型的由來|publisher=Hospital.kingnet.com.tw|accessdate=2010-08-01}}</ref> |

|||

The presence or absence of the Rh(D) antigen is signified by the + or − sign, so that, for example, the A− group is ABO type A and does not have the Rh (D) antigen. |

|||

===ABO and Rh distribution by country=== |

|||

{{main|Blood type distribution by country}} |

|||

As with many other genetic traits, the distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups varies significantly between populations. |

|||

===Other blood group systems=== |

|||

{{Main|Human blood group systems}} |

|||

33 blood-group systems have been identified, including the ABO and Rh systems.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url= http://www.uvm.edu/~uvmpr/?Page=news&storyID=13259 |

|||

|title=Blood Mystery Solved |

|||

|author=Joshua E. Brown |

|||

|date=22 February 2012 |

|||

|publisher=University Of Vermont |

|||

|accessdate=11 June 2012}}</ref> Thus, in addition to the ABO antigens and Rh antigens, many other antigens are expressed on the RBC surface membrane. For example, an individual can be AB, D positive, and at the same time M and N positive ([[MNS antigen system|MNS system]]), K positive ([[Kell antigen system|Kell system]]), Le<sup>a</sup> or Le<sup>b</sup> negative ([[Lewis antigen system|Lewis system]]), and so on, being positive or negative for each blood group system antigen. Many of the blood group systems were named after the patients in whom the corresponding antibodies were initially encountered. |

|||

==Clinical significance== |

|||

===Blood transfusion=== |

|||

{{Main|Blood transfusion}} |

|||

Transfusion medicine is a specialized branch of [[hematology]] that is concerned with the study of blood groups, along with the work of a [[blood bank]] to provide a [[Blood transfusion|transfusion]] service for blood and other blood products. Across the world, blood products must be prescribed by a medical doctor (licensed [[physician]] or [[surgeon]]) in a similar way as medicines. |

|||

[[File:Main symptoms of acute hemolytic reaction.png|thumb|right|220px|Main symptoms of [[acute hemolytic reaction]] due to blood type mismatch.<ref>[http://www.cancer.org/docroot/ETO/content/ETO_1_4x_Possible_Risks_of_Blood_Product_Transfusions.asp Possible Risks of Blood Product Transfusions] from American Cancer Society. Last Medical Review: 03/08/2008. Last Revised: 01/13/2009</ref><ref>[http://www.pathology.med.umich.edu/bloodbank/manual/bbch_7/index.html 7 adverse reactions to transfusion] Pathology Department at University of Michigan. Version July 2004, Revised 11/5/08</ref>]] |

|||

Much of the routine work of a [[blood bank]] involves testing blood from both donors and recipients to ensure that every individual recipient is given blood that is compatible and is as safe as possible. If a unit of incompatible blood is [[Blood transfusion|transfused]] between a [[Blood donation|donor]] and recipient, a severe [[acute hemolytic reaction]] with [[hemolysis]] (RBC destruction), [[renal failure]] and [[shock (circulatory)|shock]] is likely to occur, and death is a possibility. Antibodies can be highly active and can attack RBCs and bind components of the [[complement system]] to cause massive hemolysis of the transfused blood. |

|||

Patients should ideally receive their own blood or type-specific blood products to minimize the chance of a [[transfusion reaction]]. Risks can be further reduced by [[cross-matching]] blood, but this may be skipped when blood is required for an emergency. Cross-matching involves mixing a sample of the recipient's serum with a sample of the donor's red blood cells and checking if the mixture ''agglutinates'', or forms clumps. If agglutination is not obvious by direct vision, blood bank technicians usually check for [[Agglutination (biology)|agglutination]] with a [[microscope]]. If agglutination occurs, that particular donor's blood cannot be transfused to that particular recipient. In a blood bank it is vital that all blood specimens are correctly identified, so labelling has been standardized using a [[barcode]] system known as [[ISBT 128]]. |

|||

The blood group may be included on [[Dog tag (identifier)|identification tags]] or on [[tattoo]]s worn by military personnel, in case they should need an emergency blood transfusion. Frontline German [[SS blood group tattoo|Waffen-SS had blood group tattoos]] during [[World War II]]. |

|||

Rare blood types can cause supply problems for [[blood bank]]s and hospitals. For example, [[Duffy antigen|Duffy]]-negative blood occurs much more frequently in people of African origin,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Nickel RG |title=Determination of Duffy genotypes in three populations of African descent using PCR and sequence-specific oligonucleotides |journal=Human Immunology |volume=60 |issue=8 |pages=738–42 |date=August 1999 |pmid=10439320 |doi=10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00039-7 |author2=Willadsen SA |author3=Freidhoff LR |display-authors=3 |last4=Huang |first4=Shau-Ku |last5=Caraballo |first5=Luis |last6=Naidu |first6=Raana P |last7=Levett |first7=Paul |last8=Blumenthal |first8=Malcolm |last9=Banks-Schlegel |first9=Susan}}</ref> and the rarity of this blood type in the rest of the population can result in a shortage of Duffy-negative blood for these patients. Similarly for RhD negative people, there is a risk associated with travelling to parts of the world where supplies of RhD negative blood are rare, particularly [[East Asia]], where blood services may endeavor to encourage Westerners to donate blood.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bloodcare.org.uk/html/resources_chairman_2001.htm |title=BCF – Members – Chairman's Annual Report |accessdate=2008-07-15 |last=Bruce |first=MG |date=May 2002 |publisher=The Blood Care Foundation |quote=As Rhesus Negative blood is rare amongst local nationals, this Agreement will be of particular value to Rhesus Negative expatriates and travellers |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080410111425/http://www.bloodcare.org.uk/html/resources_chairman_2001.htm |archivedate=April 10, 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

===Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)=== |

|||

{{Main|Hemolytic disease of the newborn}} |

|||

A [[antenatal|pregnant]] woman can make [[IgG]] blood group antibodies if her fetus has a blood group antigen that she does not have. This can happen if some of the fetus' blood cells pass into the mother's blood circulation (e.g. a small fetomaternal [[bleeding|hemorrhage]] at the time of childbirth or obstetric intervention), or sometimes after a therapeutic [[blood transfusion]]. This can cause [[Rh disease]] or other forms of [[hemolytic disease of the newborn]] (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-D antibodies, the Rh blood type of a [[fetus]] can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Daniels G, Finning K, Martin P, Summers J |title=Fetal blood group genotyping: present and future |journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences |volume=1075 |issue= |pages=88–95 |date=September 2006 |pmid=17108196 |doi=10.1196/annals.1368.011}}</ref> One of the major advances of twentieth century medicine was to prevent this disease by stopping the formation of Anti-D antibodies by D negative mothers with an injectable medication called [[Rho(D) immune globulin]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=1972 |title=Use of Anti-D Immunoglobulin for Rh Prophylaxis |publisher=[[Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists]] |date=May 2002 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081230200349/http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=1972 |archivedate=December 30, 2008 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url =http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA41/?c=91520 |title = Pregnancy – routine anti-D prophylaxis for D-negative women |publisher = [[National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence|NICE]] |date=May 2002}}</ref> Antibodies associated with some blood groups can cause severe HDN, others can only cause mild HDN and others are not known to cause HDN.<ref name="Letsky2000"/> |

|||

=== Blood products === |

|||

To provide maximum benefit from each blood donation and to extend shelf-life, [[blood bank]]s [[blood fractionation|fractionate]] some whole blood into several products. The most common of these products are packed RBCs, [[Blood plasma|plasma]], [[platelet]]s, [[cryoprecipitate]], and [[Blood plasma#Fresh frozen plasma|fresh frozen plasma]] (FFP). FFP is quick-frozen to retain the labile [[clotting factor]]s [[Factor V|V]] and [[Factor VIII|VIII]], which are usually administered to patients who have a potentially fatal clotting problem caused by a condition such as advanced [[liver]] disease, overdose of [[anticoagulant]], or [[disseminated intravascular coagulation]] (DIC). |

|||

Units of packed red cells are made by removing as much of the plasma as possible from whole blood units. |

|||

[[Clotting factors]] synthesized by modern [[Recombinant DNA|recombinant]] methods are now in routine clinical use for [[hemophilia]], as the risks of infection transmission that occur with pooled blood products are avoided. |

|||

===Red blood cell compatibility=== |

|||

*'''Blood group AB''' individuals have both A and B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their [[blood plasma]] does not contain any antibodies against either A or B antigen. Therefore, an individual with type AB blood can receive blood from any group (with AB being preferable), but cannot donate blood to any group other than AB. They are known as universal recipients. |

|||

*'''Blood group A''' individuals have the A antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing [[IgM]] antibodies against the B antigen. Therefore, a group A individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups A or O (with A being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type A or AB. |

|||

*'''Blood group B''' individuals have the B antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the A antigen. Therefore, a group B individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups B or O (with B being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type B or AB. |

|||

*'''Blood group O''' (or blood group zero in some countries) individuals do not have either A or B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood serum contains IgM anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Therefore, a group O individual can receive blood only from a group O individual, but can donate blood to individuals of any ABO blood group (i.e., A, B, O or AB). If a patient in a hospital situation needs a blood transfusion in an emergency, and if the time taken to process the recipient's blood would cause a detrimental delay, O negative blood can be issued. Because it is compatible with anyone, O negative blood is often overused and consequently is always in short supply.<ref name="AABBfive">{{Citation |author1 = American Association of Blood Banks |author1-link = American Association of Blood Banks |date = 24 April 2014 |title = Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |publisher = American Association of Blood Banks |work = [[Choosing Wisely]]: an initiative of the [[ABIM Foundation]] |page = |url = http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-association-of-blood-banks/ |accessdate = 25 July 2014}}, which cites |

|||

*{{cite web|author1=The Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee|title=The appropriate use of group O RhD negative red cells|url=http://hospital.blood.co.uk/library/pdf/nbtc_bbt_o_neg_red_cells_recs_09_04.pdf|publisher=[[National Health Service]]|accessdate=25 July 2014|year=c. 2008}}</ref> According to the American Association of Blood Banks and the British Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee, the use of group O RhD negative red cells should be restricted to persons with O negative blood, women who might be pregnant, and emergency cases in which blood-group testing is genuinely impracticable.<ref name="AABBfive"/> |

|||

[[Image:Blood Compatibility.svg|right|230px|thumb|'''Red blood cell compatibility chart'''<br />In addition to donating to the same blood group; type O blood donors can give to A, B and AB; blood donors of types A and B can give to AB.]] |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

|+ Red blood cell compatibility table<!-- |

|||

--><ref name=rbccomp>{{cite web |url=http://chapters.redcross.org/br/northernohio/INFO/bloodtype.html |title=RBC compatibility table |accessdate=2008-07-15 |date=December 2006 |publisher=American National Red Cross }}</ref><ref name=bloodbook>[http://www.bloodbook.com/compat.html Blood types and compatibility] bloodbook.com</ref><!-- |

|||

--> |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | Recipient<sup>[1]</sup> |

|||

! colspan="8" | Donor<sup>[1]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|||

! O− |

|||

! O+ |

|||

! A− |

|||

! A+ |

|||

! B− |

|||

! B+ |

|||

! AB− |

|||

! AB+ |

|||

|- |

|||

! O− |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{Y}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

| style="width:3em" | {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! O+ |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! A− |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! A+ |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! B− |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! B+ |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! AB− |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! AB+ |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

|} |

|||

<small> |

|||

Table note<br /> |

|||

1. Assumes absence of atypical antibodies that would cause an incompatibility between donor and recipient blood, as is usual for blood selected by cross matching. |

|||

</small> |

|||

An Rh D-negative patient who does not have any anti-D antibodies (never being previously sensitized to D-positive RBCs) can receive a transfusion of D-positive blood once, but this would cause sensitization to the D antigen, and a female patient would become at risk for [[hemolytic disease of the newborn]]. If a D-negative patient has developed anti-D antibodies, a subsequent exposure to D-positive blood would lead to a potentially dangerous transfusion reaction. Rh D-positive blood should never be given to D-negative women of child bearing age or to patients with D antibodies, so blood banks must conserve Rh-negative blood for these patients. In extreme circumstances, such as for a major bleed when stocks of D-negative blood units are very low at the blood bank, D-positive blood might be given to D-negative females above child-bearing age or to Rh-negative males, providing that they did not have anti-D antibodies, to conserve D-negative blood stock in the blood bank. The converse is not true; Rh D-positive patients do not react to D negative blood. |

|||

This same matching is done for other antigens of the Rh system as C, c, E and e and for other blood group systems with a known risk for immunization such as the Kell system in particular for females of child-bearing age or patients with known need for many transfusions. |

|||

===Plasma compatibility=== |

|||

[[File:Plasma donation compatibility path.svg|right|190px|thumb|'''Plasma compatibility chart'''<br />In addition to donating to the same blood group; plasma from type AB can be given to A, B and O; plasma from types A, B and AB can be given to O.]] |

|||

[[Blood plasma]] compatibility is the inverse of red blood cell compatibility.<ref>{{cite web|title=Blood Component ABO Compatibility Chart Red Blood Cells and Plasma|url=http://www.pathology.med.umich.edu|website=Blood Bank Labsite|publisher=University of Michigan|accessdate=16 December 2014}}</ref> Type AB plasma carries neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies and can be transfused to individuals of any blood group; but type AB patients can only receive type AB plasma. Type O carries both antibodies, so individuals of blood group O can receive plasma from any blood group, but type O plasma can be used only by type O recipients. |

|||

<!--Please don't switch donor and recipient here without being absolutely sure they're wrong. Check the cited source; any change must match it. It seems a lot of people switch this without actually understanding it, because it's often edited from the correct (AB can donate plasma to all blood groups) to the wrong.--> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

|+ Plasma compatibility table<ref name=bloodbook /> |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Recipient |

|||

! colspan="4" | Donor<sup>[1]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="width:3em" | O |

|||

! style="width:3em" | A |

|||

! style="width:3em" | B |

|||

! style="width:3em" | AB |

|||

|- |

|||

! O |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! A |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! B |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! AB |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{N}} |

|||

| {{Y}} |

|||

|} |

|||

<small> |

|||

Table note<br /> |

|||

1. Assumes absence of strong atypical antibodies in donor plasma |

|||

</small> |

|||

Rh D antibodies are uncommon, so generally neither D negative nor D positive blood contain anti-D antibodies. If a potential donor is found to have anti-D antibodies or any strong atypical blood group antibody by antibody screening in the blood bank, they would not be accepted as a donor (or in some blood banks the blood would be drawn but the product would need to be appropriately labeled); therefore, donor blood plasma issued by a blood bank can be selected to be free of D antibodies and free of other atypical antibodies, and such donor plasma issued from a blood bank would be suitable for a recipient who may be D positive or D negative, as long as blood plasma and the recipient are ABO compatible.{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} |

|||

===Universal donors and universal recipients=== |

|||

[[File:US Navy 060105-N-8154G-010 A hospital corpsman with the Blood Donor Team from Portsmouth Naval Hospital takes samples of blood from a donor for testing.jpg|thumb|right|220px|A hospital corpsman with the Blood Donor Team from [[Naval Medical Center Portsmouth]] takes samples of blood from a donor for testing]] |

|||

With regard to transfusions of packed red blood cells, individuals with type O Rh D negative blood are often called universal donors, and those with type AB Rh D positive blood are called universal recipients; however, these terms are only generally true with respect to possible reactions of the recipient's anti-A and anti-B antibodies to transfused red blood cells, and also possible sensitization to Rh D antigens. One exception is individuals with [[hh antigen system]] (also known as the Bombay phenotype) who can only receive blood safely from other hh donors, because they form antibodies against the H antigen present on all red blood cells.<ref>{{cite book |title=Harrison's Principals of Internal Medicine |last=Fauci |first=Anthony S. |author2=Eugene Braunwald|author3=Kurt J. Isselbacher|author4=Jean D. Wilson|author5=Joseph B. Martin|author6=Dennis L. Kasper|author7=Stephen L. Hauser|author8=Dan L. Longo |year=1998 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn= 0-07-020291-5 |page=719 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/blood-type-test |title=Universal acceptor and donor groups |publisher=Webmd.com |date=2008-06-12 |accessdate=2010-08-01}}</ref> |

|||

Blood donors with exceptionally strong anti-A, anti-B or any atypical blood group antibody may be excluded from blood donation. In general, while the plasma fraction of a blood transfusion may carry donor antibodies not found in the recipient, a significant reaction is unlikely because of dilution. |

|||

Additionally, red blood cell surface antigens other than A, B and Rh D, might cause adverse reactions and sensitization, if they can bind to the corresponding antibodies to generate an immune response. Transfusions are further complicated because [[platelet]]s and [[white blood cell]]s (WBCs) have their own systems of surface antigens, and sensitization to platelet or WBC antigens can occur as a result of transfusion. |

|||

With regard to transfusions of [[Plasma (blood)|plasma]], this situation is reversed. Type O plasma, containing both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, can only be given to O recipients. The antibodies will attack the antigens on any other blood type. Conversely, AB plasma can be given to patients of any ABO blood group due to not containing any anti-A or anti-B antibodies. |

|||

==Blood group genotyping== |

|||

In addition to the current practice of serologic testing of blood types, the progress in molecular diagnostics allows the increasing use of blood group genotyping. In contrast to serologic tests reporting a direct blood type phenotype, genotyping allows the prediction of a phenotype based on the knowledge of the molecular basis of the currently known antigens. This allows a more detailed determination of the blood type and therefore a better match for transfusion, which can be crucial in particular for patients with needs for many transfusions to prevent allo-immunization.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Anstee DJ |title=Red cell genotyping and the future of pretransfusion testing |journal=Blood |volume=114|issue=2|year= 2009|doi= 10.1182/blood-2008-11-146860|pmid=19411635| pages=248–56}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Avent ND |title=Large-scale blood group genotyping: clinical implications |journal=Br J Haematol |volume=144|issue=1|year= 2009|doi= 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07285.x|pmid=19016734| pages=3–13}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

[[File:Karl Landsteiner, 1920s..jpg|thumb|upright|[[Karl Landsteiner]]]] |

|||

Two blood group systems were discovered by [[Karl Landsteiner]] during early experiments with blood transfusion: the [[ABO blood group system|ABO group]] in 1901<ref>{{cite journal |author=Landsteiner K |title=Zur Kenntnis der antifermentativen, lytischen und agglutinierenden Wirkungen des Blutserums und der Lymphe |journal=Zentralblatt Bakteriologie |volume=27 |issue= |pages=357–62 |year=1900 |doi= |url=}}</ref>{{full citation needed|date=January 2016}} and in co-operation with [[Alexander S. Wiener]] the [[Rhesus blood group system|Rhesus group]] in 1937.<ref name="Farr1979">{{cite journal |author=Farr AD |title=Blood group serology—the first four decades (1900–1939) |journal=Medical History |volume=23 |issue=2 |pages=215–26 |date=April 1979 |pmid=381816 |pmc=1082436 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300051383}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Landsteiner K, Wiener AS |title=An agglutinable factor in human blood recognized by immune sera for rhesus blood |journal=Proc Soc Exp Biol Med |volume=43 |issue= |pages=223–4 |year=1940 |doi= 10.3181/00379727-43-11151|url=}}</ref> Development of the [[Coombs test]] in 1945,<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Coombs RR, Mourant AE, Race RR |title=A new test for the detection of weak and incomplete Rh agglutinins |journal=Br J Exp Pathol |volume=26 |issue= |pages=255–66 |year=1945 |pmid=21006651 |pmc=2065689 }}</ref> |

|||

the advent of [[transfusion medicine]], and the understanding of [[ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn]] led to discovery of more blood groups, and now 33 [[human blood group systems]] are recognized by the [[International Society of Blood Transfusion]] (ISBT),<ref name=iccbba/> and in the 33 blood groups, over 600 blood group antigens have been found;<ref name="newenglandblood1"/> many of these are rare or are mainly found in certain ethnic groups. |

|||

[[Czechs|Czech]] [[serology|serologist]] [[Jan Janský]] is credited with the first classification of blood into the four types (A, B, AB, O) in 1907, which remains in use today. Blood types have been used in [[forensic science]] and were formerly used to demonstrate impossibility of [[DNA paternity testing|paternity]] (e.g., a type AB man cannot be the father of a type O infant), but both of these uses are being replaced by [[genetic fingerprinting]], which provides greater certainty.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Johnson P, Williams R, Martin P |title=Genetics and Forensics: Making the National DNA Database |journal=Science Studies |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=22–37 |year=2003 |pmid=16467921 |pmc=1351151}}</ref> |

|||

According to the [http://www.bmg.gv.at/home/EN/Home Austrian Federal Ministry of Health]{{full citation needed|date=January 2016}} the original terminology used by Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is A, B and 0 (''zero''); the "O" (''oh'') you find in the ABO group system is actually a subsequent variation occurred during the translation process, probably due to the similar shape between the number 0 and the letter O. |

|||

==Society and culture== |

|||

{{Main|Blood type personality theory}} |

|||

A popular belief in Japan is that a person's ABO blood type is predictive of their [[Personality psychology|personality]], [[moral character|character]], and [[Interpersonal compatibility|compatibility with others]]. This belief is also widespread in [[South Korea]]<ref name=AP>{{cite news|url=http://www.medbroadcast.com/channel_health_news_details.asp?news_id=17166&channel_id=1000 |title=Despite scientific debunking, in Japan you are what your blood type is |agency=Associated Press |publisher=MediResource Inc. |accessdate=2011-08-13 |date=2009-02-01 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928021954/http://www.medbroadcast.com/channel_health_news_details.asp?news_id=17166&channel_id=1000 |archivedate=September 28, 2011 }}</ref> and [[Taiwan]]. Deriving from ideas of historical [[scientific racism]], the theory reached Japan in a 1927 psychologist's report, and the militarist government of the time commissioned a study aimed at breeding better soldiers.<ref name="AP"/> The fad faded in the 1930s due to its lack of scientific basis and ultimately the discovery of DNA in the following decades which it later became clear had a vastly more complex and important role in both heredity generally and personality specifically. No evidence has been found to support the theory by scientists, but it was revived in the 1970s by [[Masahiko Nomi]], a broadcaster with a background in law who had no scientific or medical background.<ref name="AP"/> Despite these facts, the myth still persists widely in Japanese and South Korean popular culture.<ref name=Nuwer>{{cite web|last=Nuwer|first=Rachel|title=You are what you bleed: In Japan and other east Asian countries some believe blood type dictates personality|url=http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2011/02/15/you-are-what-you-bleed-in-japan-and-other-east-asian-countries-some-believe-blood-type-dictates-personality/|publisher=Scientific American|accessdate=16 Feb 2011}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[hh blood group]] |

|||

*[[Blood type (non-human)]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

*{{cite book |title = Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens, a guide to the differences in our blood types that complicate blood transfusions and pregnancy |last = Dean |first = Laura |publisher = [[National Center for Biotechnology Information]] |location=Bethesda MD |year=2005 |id=NBK2261 |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2261/ |ref=harv |isbn=1-932811-05-2}} |

|||

*{{cite book |vauthors=Mollison PL, Engelfriet CP, Contreras M |title=Blood Transfusion in Clinical Medicine |publisher=Blackwell Science |location=Oxford UK |year=1997 |isbn=0-86542-881-6 |edition=10th }} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*[http://bloodgroupbank.com/ www.BloodGroupBank.com Know Blood Group Information of your friends] |

|||

*[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gv/mhc/xslcgi.cgi?cmd=bgmut/home BGMUT] Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database at [[National Center for Biotechnology Information|NCBI]], [[NIH]] has details of genes and proteins, and variations thereof, that are responsible for blood types |

|||

* {{OMIM|110300|ABO Glycosyltransferase; ABO}} |

|||

* {{OMIM|111680|Rhesus Blood Group, D Antigen; RHD}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url = http://www.gentest.ch/index.php?content=bloodtype&langchange=en |title= Blood group test, Gentest.ch |accessdate= 2006-07-07 |publisher= Gentest.ch GmbH}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url = http://www.lifeshare.org/facts/raretraits.htm | title = Blood Facts – Rare Traits | accessdate = September 15, 2006 | publisher = LifeShare Blood Centers}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url = http://anthro.palomar.edu/vary/vary_3.htm | title = Modern Human Variation: Distribution of Blood Types | accessdate = November 23, 2006 |date= 2001-06-06 |publisher= Dr. Dennis O'Neil, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marcos, California |archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20060221332211/http://anthro.palomar.edu/vary/vary_3.htm| archivedate= 2006-02-21}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url = http://www.bloodbook.com/world-abo.html | title = Racial and Ethnic Distribution of ABO Blood Types – BloodBook.com, Blood Information for Life | accessdate = September 15, 2006 | publisher = bloodbook.com}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url = http://abobloodgroup.googlepages.com/home | title = Molecular Genetic Basis of ABO | accessdate = July 31, 2008 | publisher =}} |

|||

* [http://www.pleacher.com/mp/mlessons/stat/blood2.html Blood types] – intuitive explanation using [[Venn diagram]]s |

|||

{{Transfusion medicine}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Blood Type}} |

|||

[[Category:Blood|Type]] |

|||

[[Category:Genetics]] |

|||

[[Category:Hematology]] |

|||

[[Category:Transfusion medicine]] |

|||

[[Category:Antigens]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:36, 23 March 2017

A blood type (also called a blood group) is a classification of blood based on the presence and absence of antibodies and also based on the presence or absence of inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system. Some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of cells of various tissues. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens can stem from one allele (or an alternative version of a gene) and collectively form a blood group system.[1] Blood types are inherited and represent contributions from both parents. A total of 35 human blood group systems are now recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT).[2] The two most important ones are ABO and the RhD antigen; they determine someone's blood type (A, B, AB and O, with +, − or Null denoting RhD status).

Many pregnant women carry a fetus with a blood type which is different from their own, which is not a problem. What can matter is whether the baby is RhD positive or negative. Mothers who are RhD- and carry a RhD+ baby can form antibodies against fetal RBCs. Sometimes these maternal antibodies are IgG, a small immunoglobulin, which can cross the placenta and cause hemolysis of fetal RBCs, which in turn can lead to hemolytic disease of the newborn called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness of low fetal blood counts that ranges from mild to severe. Sometimes this is lethal for the fetus; in these cases it is called hydrops fetalis.[3]

Blood group systems

A complete blood type would describe a full set of 30 substances on the surface of RBCs, and an individual's blood type is one of many possible combinations of blood-group antigens.[4] Across the 35 blood groups, over 600 different blood-group antigens have been found,[5]Almost always, an individual has the same blood group for life, but very rarely an individual's blood type changes through addition or suppression of an antigen in infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.[6][7][8][9] Another more common cause in blood type change is a bone marrow transplant. Bone-marrow transplants are performed for many leukemias and lymphomas, among other diseases. If a person receives bone marrow from someone who is a different ABO type (e.g., a type A patient receives a type O bone marrow), the patient's blood type will eventually convert to the donor's type.

Some blood types are associated with inheritance of other diseases; for example, the Kell antigen is sometimes associated with McLeod syndrome.[10] Certain blood types may affect susceptibility to infections, an example being the resistance to specific malaria species seen in individuals lacking the Duffy antigen.[11] The Duffy antigen, presumably as a result of natural selection, is more common in ethnic groups from areas with a high incidence of malaria.[12]

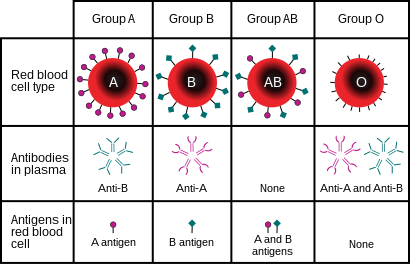

ABO blood group system

In human blood there are two antigens and antibodies. The two antigens are antigen A and antigen B. The two antibodies are antibody A and antibody B. The antigens are present in the red blood cells and the antibodies in the serum. Regarding the antigen property of the blood all human beings can be classified into 4 groups, those with antigen A (group A), those with antigen B (group B), those with both antigen A and B (group AB) and those with neither antigen (group O). The antibodies present together with the antigens are found as follows : 1. Antigen A with antibody B 2. Antigen B with antibody A 3. Antigen AB has no antibodies 4. Antigen nil (group O) with antibody A and B.

There is an agglutination reaction between similar antigen and antibody (for example, antigen A agglutinates the antibody A and antigen B agglutinates the antibody B) Thus, transfusion can be considered safe as long as the serum of the recipient does not contain antibodies for the blood cell antigens of the donor.

The ABO system is the most important blood-group system in human-blood transfusion. The associated anti-A and anti-B antibodies are usually immunoglobulin M, abbreviated IgM, antibodies. ABO IgM antibodies are produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, bacteria, and viruses. The original terminology used by Dr. Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is A/B/C; in later publications "C" became "O".[13] "O" is often called 0 (zero, or null) in other languages. The Austrian Federal Ministry of Health claims the original terminology used by Dr. Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is 0(Zero)/A/B/AB and that in later publications "0" became "O" in most of English language countries.[13][14]

| Phenotype | Genotype |

|---|---|

| A | AA or AO |

| B | BB or BO |

| AB | AB |

| O | OO |

Rh blood group system

The Rh system (Rh meaning Rhesus) is the second most significant blood-group system in human-blood transfusion with currently 50 antigens. The most significant Rh antigen is the D antigen, because it is the most likely to provoke an immune system response of the five main Rh antigens. It is common for D-negative individuals not to have any anti-D IgG or IgM antibodies, because anti-D antibodies are not usually produced by sensitization against environmental substances. However, D-negative individuals can produce IgG anti-D antibodies following a sensitizing event: possibly a fetomaternal transfusion of blood from a fetus in pregnancy or occasionally a blood transfusion with D positive RBCs.[15] Rh disease can develop in these cases.[16] Rh negative blood types are much less common in Asian populations (0.3%) than they are in White populations (15%).[17] The presence or absence of the Rh(D) antigen is signified by the + or − sign, so that, for example, the A− group is ABO type A and does not have the Rh (D) antigen.

ABO and Rh distribution by country

As with many other genetic traits, the distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups varies significantly between populations.

Other blood group systems

33 blood-group systems have been identified, including the ABO and Rh systems.[18] Thus, in addition to the ABO antigens and Rh antigens, many other antigens are expressed on the RBC surface membrane. For example, an individual can be AB, D positive, and at the same time M and N positive (MNS system), K positive (Kell system), Lea or Leb negative (Lewis system), and so on, being positive or negative for each blood group system antigen. Many of the blood group systems were named after the patients in whom the corresponding antibodies were initially encountered.

Clinical significance

Blood transfusion

Transfusion medicine is a specialized branch of hematology that is concerned with the study of blood groups, along with the work of a blood bank to provide a transfusion service for blood and other blood products. Across the world, blood products must be prescribed by a medical doctor (licensed physician or surgeon) in a similar way as medicines.

Much of the routine work of a blood bank involves testing blood from both donors and recipients to ensure that every individual recipient is given blood that is compatible and is as safe as possible. If a unit of incompatible blood is transfused between a donor and recipient, a severe acute hemolytic reaction with hemolysis (RBC destruction), renal failure and shock is likely to occur, and death is a possibility. Antibodies can be highly active and can attack RBCs and bind components of the complement system to cause massive hemolysis of the transfused blood.

Patients should ideally receive their own blood or type-specific blood products to minimize the chance of a transfusion reaction. Risks can be further reduced by cross-matching blood, but this may be skipped when blood is required for an emergency. Cross-matching involves mixing a sample of the recipient's serum with a sample of the donor's red blood cells and checking if the mixture agglutinates, or forms clumps. If agglutination is not obvious by direct vision, blood bank technicians usually check for agglutination with a microscope. If agglutination occurs, that particular donor's blood cannot be transfused to that particular recipient. In a blood bank it is vital that all blood specimens are correctly identified, so labelling has been standardized using a barcode system known as ISBT 128.

The blood group may be included on identification tags or on tattoos worn by military personnel, in case they should need an emergency blood transfusion. Frontline German Waffen-SS had blood group tattoos during World War II.

Rare blood types can cause supply problems for blood banks and hospitals. For example, Duffy-negative blood occurs much more frequently in people of African origin,[21] and the rarity of this blood type in the rest of the population can result in a shortage of Duffy-negative blood for these patients. Similarly for RhD negative people, there is a risk associated with travelling to parts of the world where supplies of RhD negative blood are rare, particularly East Asia, where blood services may endeavor to encourage Westerners to donate blood.[22]

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)

A pregnant woman can make IgG blood group antibodies if her fetus has a blood group antigen that she does not have. This can happen if some of the fetus' blood cells pass into the mother's blood circulation (e.g. a small fetomaternal hemorrhage at the time of childbirth or obstetric intervention), or sometimes after a therapeutic blood transfusion. This can cause Rh disease or other forms of hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-D antibodies, the Rh blood type of a fetus can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease.[23] One of the major advances of twentieth century medicine was to prevent this disease by stopping the formation of Anti-D antibodies by D negative mothers with an injectable medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.[24][25] Antibodies associated with some blood groups can cause severe HDN, others can only cause mild HDN and others are not known to cause HDN.[3]

Blood products

To provide maximum benefit from each blood donation and to extend shelf-life, blood banks fractionate some whole blood into several products. The most common of these products are packed RBCs, plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP). FFP is quick-frozen to retain the labile clotting factors V and VIII, which are usually administered to patients who have a potentially fatal clotting problem caused by a condition such as advanced liver disease, overdose of anticoagulant, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Units of packed red cells are made by removing as much of the plasma as possible from whole blood units.

Clotting factors synthesized by modern recombinant methods are now in routine clinical use for hemophilia, as the risks of infection transmission that occur with pooled blood products are avoided.

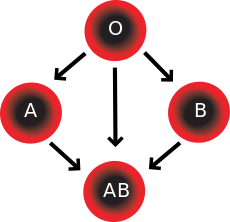

Red blood cell compatibility

- Blood group AB individuals have both A and B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood plasma does not contain any antibodies against either A or B antigen. Therefore, an individual with type AB blood can receive blood from any group (with AB being preferable), but cannot donate blood to any group other than AB. They are known as universal recipients.

- Blood group A individuals have the A antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the B antigen. Therefore, a group A individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups A or O (with A being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type A or AB.

- Blood group B individuals have the B antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the A antigen. Therefore, a group B individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups B or O (with B being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type B or AB.

- Blood group O (or blood group zero in some countries) individuals do not have either A or B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood serum contains IgM anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Therefore, a group O individual can receive blood only from a group O individual, but can donate blood to individuals of any ABO blood group (i.e., A, B, O or AB). If a patient in a hospital situation needs a blood transfusion in an emergency, and if the time taken to process the recipient's blood would cause a detrimental delay, O negative blood can be issued. Because it is compatible with anyone, O negative blood is often overused and consequently is always in short supply.[26] According to the American Association of Blood Banks and the British Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee, the use of group O RhD negative red cells should be restricted to persons with O negative blood, women who might be pregnant, and emergency cases in which blood-group testing is genuinely impracticable.[26]

In addition to donating to the same blood group; type O blood donors can give to A, B and AB; blood donors of types A and B can give to AB.

| Recipient[1] | Donor[1] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O− | O+ | A− | A+ | B− | B+ | AB− | AB+ | |

| O− | ||||||||

| O+ | ||||||||

| A− | ||||||||

| A+ | ||||||||

| B− | ||||||||

| B+ | ||||||||

| AB− | ||||||||

| AB+ | ||||||||

Table note

1. Assumes absence of atypical antibodies that would cause an incompatibility between donor and recipient blood, as is usual for blood selected by cross matching.

An Rh D-negative patient who does not have any anti-D antibodies (never being previously sensitized to D-positive RBCs) can receive a transfusion of D-positive blood once, but this would cause sensitization to the D antigen, and a female patient would become at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn. If a D-negative patient has developed anti-D antibodies, a subsequent exposure to D-positive blood would lead to a potentially dangerous transfusion reaction. Rh D-positive blood should never be given to D-negative women of child bearing age or to patients with D antibodies, so blood banks must conserve Rh-negative blood for these patients. In extreme circumstances, such as for a major bleed when stocks of D-negative blood units are very low at the blood bank, D-positive blood might be given to D-negative females above child-bearing age or to Rh-negative males, providing that they did not have anti-D antibodies, to conserve D-negative blood stock in the blood bank. The converse is not true; Rh D-positive patients do not react to D negative blood.

This same matching is done for other antigens of the Rh system as C, c, E and e and for other blood group systems with a known risk for immunization such as the Kell system in particular for females of child-bearing age or patients with known need for many transfusions.

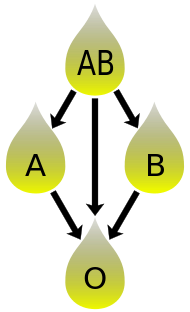

Plasma compatibility

In addition to donating to the same blood group; plasma from type AB can be given to A, B and O; plasma from types A, B and AB can be given to O.

Blood plasma compatibility is the inverse of red blood cell compatibility.[29] Type AB plasma carries neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies and can be transfused to individuals of any blood group; but type AB patients can only receive type AB plasma. Type O carries both antibodies, so individuals of blood group O can receive plasma from any blood group, but type O plasma can be used only by type O recipients.

| Recipient | Donor[1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | A | B | AB | |

| O | ||||

| A | ||||

| B | ||||

| AB | ||||

Table note

1. Assumes absence of strong atypical antibodies in donor plasma

Rh D antibodies are uncommon, so generally neither D negative nor D positive blood contain anti-D antibodies. If a potential donor is found to have anti-D antibodies or any strong atypical blood group antibody by antibody screening in the blood bank, they would not be accepted as a donor (or in some blood banks the blood would be drawn but the product would need to be appropriately labeled); therefore, donor blood plasma issued by a blood bank can be selected to be free of D antibodies and free of other atypical antibodies, and such donor plasma issued from a blood bank would be suitable for a recipient who may be D positive or D negative, as long as blood plasma and the recipient are ABO compatible.[citation needed]

Universal donors and universal recipients

With regard to transfusions of packed red blood cells, individuals with type O Rh D negative blood are often called universal donors, and those with type AB Rh D positive blood are called universal recipients; however, these terms are only generally true with respect to possible reactions of the recipient's anti-A and anti-B antibodies to transfused red blood cells, and also possible sensitization to Rh D antigens. One exception is individuals with hh antigen system (also known as the Bombay phenotype) who can only receive blood safely from other hh donors, because they form antibodies against the H antigen present on all red blood cells.[30][31]

Blood donors with exceptionally strong anti-A, anti-B or any atypical blood group antibody may be excluded from blood donation. In general, while the plasma fraction of a blood transfusion may carry donor antibodies not found in the recipient, a significant reaction is unlikely because of dilution.

Additionally, red blood cell surface antigens other than A, B and Rh D, might cause adverse reactions and sensitization, if they can bind to the corresponding antibodies to generate an immune response. Transfusions are further complicated because platelets and white blood cells (WBCs) have their own systems of surface antigens, and sensitization to platelet or WBC antigens can occur as a result of transfusion.

With regard to transfusions of plasma, this situation is reversed. Type O plasma, containing both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, can only be given to O recipients. The antibodies will attack the antigens on any other blood type. Conversely, AB plasma can be given to patients of any ABO blood group due to not containing any anti-A or anti-B antibodies.

Blood group genotyping

In addition to the current practice of serologic testing of blood types, the progress in molecular diagnostics allows the increasing use of blood group genotyping. In contrast to serologic tests reporting a direct blood type phenotype, genotyping allows the prediction of a phenotype based on the knowledge of the molecular basis of the currently known antigens. This allows a more detailed determination of the blood type and therefore a better match for transfusion, which can be crucial in particular for patients with needs for many transfusions to prevent allo-immunization.[32][33]

History

Two blood group systems were discovered by Karl Landsteiner during early experiments with blood transfusion: the ABO group in 1901[34][full citation needed] and in co-operation with Alexander S. Wiener the Rhesus group in 1937.[35][36] Development of the Coombs test in 1945,[37] the advent of transfusion medicine, and the understanding of ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn led to discovery of more blood groups, and now 33 human blood group systems are recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT),[4] and in the 33 blood groups, over 600 blood group antigens have been found;[5] many of these are rare or are mainly found in certain ethnic groups.

Czech serologist Jan Janský is credited with the first classification of blood into the four types (A, B, AB, O) in 1907, which remains in use today. Blood types have been used in forensic science and were formerly used to demonstrate impossibility of paternity (e.g., a type AB man cannot be the father of a type O infant), but both of these uses are being replaced by genetic fingerprinting, which provides greater certainty.[38]

According to the Austrian Federal Ministry of Health[full citation needed] the original terminology used by Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification is A, B and 0 (zero); the "O" (oh) you find in the ABO group system is actually a subsequent variation occurred during the translation process, probably due to the similar shape between the number 0 and the letter O.

Society and culture

A popular belief in Japan is that a person's ABO blood type is predictive of their personality, character, and compatibility with others. This belief is also widespread in South Korea[39] and Taiwan. Deriving from ideas of historical scientific racism, the theory reached Japan in a 1927 psychologist's report, and the militarist government of the time commissioned a study aimed at breeding better soldiers.[39] The fad faded in the 1930s due to its lack of scientific basis and ultimately the discovery of DNA in the following decades which it later became clear had a vastly more complex and important role in both heredity generally and personality specifically. No evidence has been found to support the theory by scientists, but it was revived in the 1970s by Masahiko Nomi, a broadcaster with a background in law who had no scientific or medical background.[39] Despite these facts, the myth still persists widely in Japanese and South Korean popular culture.[40]

See also

References

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ "Table of blood group systems v4.0" (PDF). International Society of Blood Transfusion. November 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ a b E.A. Letsky; I. Leck; J.M. Bowman (2000). "Chapter 12: Rhesus and other haemolytic diseases". Antenatal & neonatal screening (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-262826-8.

- ^ a b "Table of blood group systems". International Society of Blood Transfusion. October 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ a b "American Red Cross Blood Services, New England Region, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont". American Red Cross Blood Services – New England Region. 2001. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

there are more than 600 known antigens besides A and B that characterize the proteins found on a person's red cells

- ^ Dean 2005, The ABO blood group "... A number of illnesses may alter a person's ABO phenotype ..."

- ^ Stayboldt C, Rearden A, Lane TA (1987). "B antigen acquired by normal A1 red cells exposed to a patient's serum". Transfusion. 27 (1): 41–4. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27187121471.x. PMID 3810822.

- ^ Matsushita S, Imamura T, Mizuta T, Hanada M (November 1983). "Acquired B antigen and polyagglutination in a patient with gastric cancer". The Japanese Journal of Surgery. 13 (6): 540–2. doi:10.1007/BF02469500. PMID 6672386.

- ^ Kremer Hovinga I, Koopmans M, de Heer E, Bruijn J, Bajema I (2007). "Change in blood group in systemic lupus erythematosus". Lancet. 369 (9557): 186–7, author reply 187. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60099-3. PMID 17240276.

- ^ Chown B.; Lewis M.; Kaita K. (October 1957). "A new Kell blood-group phenotype". Nature. 180 (4588): 711. doi:10.1038/180711a0. PMID 13477267.

- ^ Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH (August 1976). "The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 295 (6): 302–4. doi:10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. PMID 778616.

- ^ Kwiatkowski DP (August 2005). "How Malaria Has Affected the Human Genome and What Human Genetics Can Teach Us about Malaria". American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (2): 171–92. doi:10.1086/432519. PMC 1224522. PMID 16001361.

The different geographic distributions of α thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, ovalocytosis, and the Duffy-negative blood group are further examples of the general principle that different populations have evolved different genetic variants to protect against malaria

- ^ a b Schmidt, P; Okroi, M (2001), "Also sprach Landsteiner – Blood Group 'O' or Blood Group 'NULL'", Infus Ther Transfus Med, 28 (4): 206–8, doi:10.1159/000050239

- ^ "Your blood – a textbook about blood and blood donation" (PDF). p. 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Talaro, Kathleen P. (2005). Foundations in microbiology (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 510–1. ISBN 0-07-111203-0.

- ^ Moise KJ (July 2008). "Management of rhesus alloimmunization in pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 112 (1): 164–76. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817d453c. PMID 18591322.

- ^ "Rh血型的由來". Hospital.kingnet.com.tw. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Joshua E. Brown (22 February 2012). "Blood Mystery Solved". University Of Vermont. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Possible Risks of Blood Product Transfusions from American Cancer Society. Last Medical Review: 03/08/2008. Last Revised: 01/13/2009

- ^ 7 adverse reactions to transfusion Pathology Department at University of Michigan. Version July 2004, Revised 11/5/08

- ^ Nickel RG; Willadsen SA; Freidhoff LR; et al. (August 1999). "Determination of Duffy genotypes in three populations of African descent using PCR and sequence-specific oligonucleotides". Human Immunology. 60 (8): 738–42. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00039-7. PMID 10439320.

- ^ Bruce, MG (May 2002). "BCF – Members – Chairman's Annual Report". The Blood Care Foundation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

As Rhesus Negative blood is rare amongst local nationals, this Agreement will be of particular value to Rhesus Negative expatriates and travellers

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Daniels G, Finning K, Martin P, Summers J (September 2006). "Fetal blood group genotyping: present and future". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1075: 88–95. doi:10.1196/annals.1368.011. PMID 17108196.

- ^ "Use of Anti-D Immunoglobulin for Rh Prophylaxis". Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. May 2002. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pregnancy – routine anti-D prophylaxis for D-negative women". NICE. May 2002.

- ^ a b American Association of Blood Banks (24 April 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Association of Blood Banks, retrieved 25 July 2014, which cites

- The Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee (c. 2008). "The appropriate use of group O RhD negative red cells" (PDF). National Health Service. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "RBC compatibility table". American National Red Cross. December 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ a b Blood types and compatibility bloodbook.com

- ^ "Blood Component ABO Compatibility Chart Red Blood Cells and Plasma". Blood Bank Labsite. University of Michigan. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S.; Eugene Braunwald; Kurt J. Isselbacher; Jean D. Wilson; Joseph B. Martin; Dennis L. Kasper; Stephen L. Hauser; Dan L. Longo (1998). Harrison's Principals of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill. p. 719. ISBN 0-07-020291-5.

- ^ "Universal acceptor and donor groups". Webmd.com. 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Anstee DJ (2009). "Red cell genotyping and the future of pretransfusion testing". Blood. 114 (2): 248–56. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-11-146860. PMID 19411635.

- ^ Avent ND (2009). "Large-scale blood group genotyping: clinical implications". Br J Haematol. 144 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07285.x. PMID 19016734.

- ^ Landsteiner K (1900). "Zur Kenntnis der antifermentativen, lytischen und agglutinierenden Wirkungen des Blutserums und der Lymphe". Zentralblatt Bakteriologie. 27: 357–62.

- ^ Farr AD (April 1979). "Blood group serology—the first four decades (1900–1939)". Medical History. 23 (2): 215–26. doi:10.1017/s0025727300051383. PMC 1082436. PMID 381816.

- ^ Landsteiner K, Wiener AS (1940). "An agglutinable factor in human blood recognized by immune sera for rhesus blood". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 43: 223–4. doi:10.3181/00379727-43-11151.

- ^ Coombs RR, Mourant AE, Race RR (1945). "A new test for the detection of weak and incomplete Rh agglutinins". Br J Exp Pathol. 26: 255–66. PMC 2065689. PMID 21006651.

- ^ Johnson P, Williams R, Martin P (2003). "Genetics and Forensics: Making the National DNA Database". Science Studies. 16 (2): 22–37. PMC 1351151. PMID 16467921.

- ^ a b c "Despite scientific debunking, in Japan you are what your blood type is". MediResource Inc. Associated Press. 2009-02-01. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nuwer, Rachel. "You are what you bleed: In Japan and other east Asian countries some believe blood type dictates personality". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 Feb 2011.

Further reading

- Dean, Laura (2005). Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens, a guide to the differences in our blood types that complicate blood transfusions and pregnancy. Bethesda MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. ISBN 1-932811-05-2. NBK2261.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mollison PL, Engelfriet CP, Contreras M (1997). Blood Transfusion in Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Oxford UK: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-86542-881-6.

External links

- www.BloodGroupBank.com Know Blood Group Information of your friends

- BGMUT Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database at NCBI, NIH has details of genes and proteins, and variations thereof, that are responsible for blood types

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): ABO Glycosyltransferase; ABO - 110300

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Rhesus Blood Group, D Antigen; RHD - 111680

- "Blood group test, Gentest.ch". Gentest.ch GmbH. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- "Blood Facts – Rare Traits". LifeShare Blood Centers. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- "Modern Human Variation: Distribution of Blood Types". Dr. Dennis O'Neil, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marcos, California. 2001-06-06. Archived from the original on 2006-02-21. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- "Racial and Ethnic Distribution of ABO Blood Types – BloodBook.com, Blood Information for Life". bloodbook.com. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- "Molecular Genetic Basis of ABO". Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- Blood types – intuitive explanation using Venn diagrams