Charles Manson: Difference between revisions

KolbertBot (talk | contribs) m Bot: HTTP→HTTPS |

Fishnagles (talk | contribs) m reverted manually potential vandalism |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| children = 3 |

| children = 3 |

||

| imprisoned = [[California State Prison, Corcoran|Corcoran State Prison]] |

| imprisoned = [[California State Prison, Corcoran|Corcoran State Prison]] |

||

| website = |

| website = {{URL|charlesmanson.com}} |

||

| module = {{Infobox musical artist|embed=yes |

| module = {{Infobox musical artist|embed=yes |

||

| background = solo_singer |

| background = solo_singer |

||

Revision as of 10:58, 25 August 2017

This article needs attention from an expert in Criminal Biography. The specific problem is: Cleanup and summarize. (July 2016) |

Charles Manson | |

|---|---|

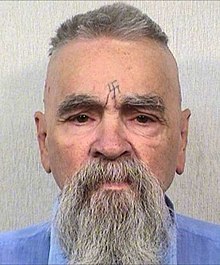

Manson in 2014 | |

| Born | Charles Milles Maddox November 12, 1934 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) |

Rosalie Willis

(m. 1955; div. 1958)Leona Stevens

(m. 1959; div. 1963) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Criminal charge | Murder, conspiracy |

| Penalty | Death (reduced to life imprisonment when death penalty was abolished in California) |

| Imprisoned at | Corcoran State Prison |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | Folk rock[1] |

| Occupation | Singer-songwriter |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1968–1970 |

| Labels | Awareness |

| Website | charlesmanson |

Charles Milles Manson (born Charles Milles Maddox, November 12, 1934)[2]: 136–7 is an American criminal, convicted mass murderer, and former cult leader who led what became known as the Manson Family, a quasi-commune that arose in California in the late 1960s. Manson's followers committed a series of nine murders at four locations in July and August 1969. In 1971 he was found guilty of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of seven people – most notably of the actress Sharon Tate – all of which were carried out by members of the group at his instruction. Manson also received first-degree murder convictions for two other deaths. He is currently serving multiple life sentences at California State Prison in Corcoran.

Manson believed in what he called "Helter Skelter", a term he took from the Beatles' song of the same name. Manson believed Helter Skelter to be an impending apocalyptic race war, which he described in his own version of the lyrics to the Beatles' song. He believed the murders would help precipitate that war. From the beginning of his notoriety, a pop culture arose around him in which he ultimately became an emblem of insanity, violence and the macabre.

At the time the Family began to form, Manson was an unemployed former convict, who had spent half of his life in correctional institutions for a variety of offenses. Before the murders, he was a singer-songwriter on the fringe of the Los Angeles music industry, chiefly through a chance association with Dennis Wilson, drummer and founding member of the Beach Boys. After Manson was charged with the crimes of which he was later convicted, recordings of songs written and performed by him were released commercially. Various musicians have covered some of his songs.

Early life

Childhood

Born to unmarried 16-year-old Kathleen Maddox (1918–1973),[3] in the General Hospital, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Manson was first named "no name Maddox."[2]: 136–7 [4][5] Within weeks, he was called Charles Milles Maddox.[2]: 136–7 [6][7]

For a period after his birth, his mother was married to laborer William Eugene Manson (May 2, 1909 – April 15, 1961).[7] His biological father appears to have been Colonel Walker Scott (May 11, 1910 – December 30, 1954)[8] against whom Kathleen Maddox filed a paternity suit that resulted in an agreed judgment in 1937. Possibly, Manson never knew his biological father.[2]: 136–7 [5]

Several statements in Manson's 1953 case file from the seven months he would later spend at the National Training School for Boys in Washington, D.C., allude to the possibility that "Colonel Scott" was black.[2]: 555 These include the first two sentences of his family background section, which read: "Father: unknown. He is alleged to have been a colored cook by the name of Scott, who got promiscuous with Charles's mother at the time of her pregnancy."[2]: 556 When asked about these official records by attorney Vincent Bugliosi in 1971, Manson emphatically denied that his biological father had black ancestry.[2]: 588 In addition, the 1920 and 1930 census list Colonel Scott and his father as white.

In the biography Manson in His Own Words, Colonel Scott is said to have been "a young drugstore cowboy ... a transient laborer working on a nearby dam project." It is not clear what "nearby" means. The description is in a paragraph that indicates Kathleen Maddox gave birth to Manson "while living in Cincinnati", after she had run away from her own home, in Ashland, Kentucky.[9]

There is much about Manson's early life that is in dispute because of the varying stories he has offered to interviewers, many of which were untrue. Manson's mother was allegedly a heavy drinker.[2]: 136–7 According to Manson, she once sold her son for a pitcher of beer to a childless waitress, from whom his uncle retrieved him some days later.[10]

When Manson's mother and her brother were sentenced to five years' imprisonment for robbing a Charleston, West Virginia, service station in 1939 by brandishing a ketchup bottle, Manson was placed in the home of an aunt and uncle in McMechen, West Virginia.[11] Upon her 1942 parole, Manson's mother retrieved her son and lived with him in a series of run-down hotel rooms.[2]: 136–7 Manson himself later characterized her physical embrace of him on the day she returned from prison as his sole happy childhood memory.[10] In 1947, Kathleen Maddox tried to have her son placed in a foster home but failed because no such home was available. The court placed Manson in the Gibault School for Boys in Terre Haute, Indiana. After 10 months, he fled from there to his mother, who rejected him.[2]: 136–7

First offenses

By burglarizing a liquor store, Manson obtained money that enabled him to rent a room.[2]: 136–7 He committed a string of burglaries of other stores, including one from which he stole a bicycle, but was eventually caught in the act and sent to an Indianapolis juvenile center. He escaped after one day, but was recaptured and placed in Boys Town. Four days after his arrival there, he escaped with another boy. The pair committed two armed robberies on their way to the home of the other boy's uncle.[2]: 137–146

Caught during the second of two subsequent break-ins of grocery stores, Manson was sent, at age 13, to the Indiana Boys School, where, he would later claim, he was brutalized sexually and otherwise.[10] After many failed attempts, he escaped with two other boys in 1951.[2]: 137–146

In Utah, the three were caught driving to California in cars they had stolen. They robbed several filling stations along the way. For the federal crime of taking a stolen car across a state line, in violation of the Dyer Act, Manson was sent to Washington, D.C.'s National Training School for Boys. Despite four years of schooling and an IQ of 109 (later tested at age 21),[2]: 137–146 he was illiterate. A caseworker deemed him aggressively antisocial.[2]: 137–146

First imprisonment

In October 1951, on a psychiatrist's recommendation, Manson was transferred to Natural Bridge Honor Camp, a minimum security institution. Manson was transferred to the Federal Reformatory, Petersburg, Virginia, where he was considered "dangerous."[2]: 137–146 In September 1952, a number of other serious disciplinary offenses resulted in his transfer to the Federal Reformatory at Chillicothe, Ohio, a more secure institution.[2]: 137–146 About a month after the transfer, he became almost a model resident. Good work habits and a rise in his educational level from the lower fourth to the upper seventh grade won him a May 1954 parole.[2]: 137–146

After temporarily honoring a parole condition that he live with his aunt and uncle in West Virginia, Manson moved in with his mother in that same state. In January 1955, he married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis, with whom, by his own account, he found genuine, if short-lived, marital happiness.[10] He supported their marriage through small-time jobs and auto theft.[2]: 137–146

Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in Los Angeles in a car he had stolen in Ohio, Manson was again charged with a federal crime, specifically another Dyer Act violation, for taking the vehicle across state lines. After a psychiatric evaluation, he was given five years' probation. His subsequent failure to appear at a Los Angeles hearing on an identical charge filed in Florida resulted in his March 1956 arrest in Indianapolis. His probation was revoked; he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment at Terminal Island, San Pedro, California.[2]: 137–146

While Manson was in prison, Rosalie gave birth to their son Charles Manson, Jr. During his first year at Terminal Island, Manson received visits from Rosalie and his mother, who were now living together in Los Angeles. In March 1957, when the visits from his wife ceased, his mother informed him Rosalie was living with another man. Less than two weeks before a scheduled parole hearing, Manson tried to escape by stealing a car. He was subsequently given five years probation, and his parole was denied.[2]: 137–146

Second imprisonment

Manson received five years' parole in September 1958, the same year in which Rosalie received a decree of divorce. By November, he was pimping a 16-year-old girl and was receiving additional support from a girl with wealthy parents. In September 1959, he pleaded guilty to a charge of attempting to cash a forged U.S. Treasury check, which he claimed to have stolen from a mailbox; the latter charge was later dropped. He received a 10-year suspended sentence and probation after a young woman with an arrest record for prostitution made a "tearful plea" before the court that she and Manson were "deeply in love ... and would marry if Charlie were freed."[2]: 137–146 Before the year's end, the woman did marry Manson, possibly so testimony against him would not be required of her.[2]: 137–146

The woman's name was Leona. As a prostitute, she had used the name Candy Stevens. After Manson took her and another woman from California to New Mexico for purposes of prostitution, he was held and questioned for violation of the Mann Act. Though he was released, he evidently suspected, rightly, that the investigation had not ended. When he disappeared, in violation of his probation, a bench warrant was issued. An April 1960 indictment for violation of the Mann Act followed.[2]: 137–146 Arrested in Laredo, Texas, in June, when one of the women was arrested for prostitution, Manson was returned to Los Angeles. For violation of his probation on the check-cashing charge, he was ordered to serve his 10-year sentence.[2]: 137–146

In July 1961, after a year spent unsuccessfully appealing the revocation of his probation, Manson was transferred from the Los Angeles County Jail to the United States Penitentiary at McNeil Island. There, he took guitar lessons from Barker-Karpis gang leader Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and obtained a contact name of someone at Universal Studios in Hollywood from another inmate, Phil Kaufman.[12] According to Jeff Guinn's 2013 biography of Manson, Charlie's mother Kathleen moved from California to Washington state to be closer to him during his McNeil Island incarceration, working nearby as a waitress.[13]

Although the Mann Act charge had been dropped, the attempt to cash the Treasury check was still a federal offense. His September 1961 annual review noted he had a "tremendous drive to call attention to himself," an observation echoed in September 1964.[2]: 137–146 In 1963, Leona was granted a divorce, in the pursuit of which she alleged that she and Manson had a son, Charles Luther.[2]: 137–146

In June 1966, Manson was sent, for the second time in his life, to Terminal Island, in preparation for early release. By March 21, 1967, his release day, he had spent more than half of his 32 years in prisons and other institutions. This was mainly because he had broken a number of federal laws. Then as now, federal sentences were much more severe than state sentences for many of the same offenses.[2]: 137–146 Telling the authorities that prison had become his home, he requested permission to stay,[2]: 137–146 a fact mentioned in a 1981 television interview with Tom Snyder.[14]

1968–69: Manson Family crimes

This section should include a summary of Manson Family. (December 2016) |

1971–present: third imprisonment

Vincent Bugliosi headed the prosecution team which argued People v. Manson, Charles Milles et al. and People v. Watson, Charles, the two major court cases that involved the Manson Family's crimes, and in Helter Skelter, he explained[where?] to his co-author, Curt Gentry, "...I was only sending him home. Only this time it won't be the same." He noted that one of the crimes of which Manson had been convicted, killing a pregnant woman, did not allow Manson to rank very high in prison social structures (Bugliosi cited an informant[who?] whom he quoted as saying that "it's like being a child molester...guys like that are gonna do hard time wherever they are") and that Manson's notoriety had become his own worst enemy, with any convict seeking a reputation being willing to attack, and kill, Manson. As noted below, in September 1984, at least one such convict did indeed so attack Manson, with intent to kill.

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring and Leno and Rosemary La Bianca. He was sentenced to death. When the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, he was resentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His original death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson received a first-degree murder conviction from Los Angeles County for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman and another first-degree murder conviction for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea.

Since 1989, Manson has been housed in the Protective Housing Unit at California State Prison, Corcoran, in Kings County. The unit houses inmates whose safety would be endangered by general population housing. He has also been housed at San Quentin State Prison, California Medical Facility in Vacaville, Folsom State Prison and Pelican Bay State Prison.

Manson is single-celled.

1980s–1990s

In the 1980s, Manson gave four notable interviews. The first, recorded at California Medical Facility and aired June 13, 1981, was by Tom Snyder for NBC's The Tomorrow Show. The second, recorded at San Quentin Prison and aired March 7, 1986, was by Charlie Rose for CBS News Nightwatch; it won the national news Emmy Award for "Best Interview" in 1987.[15] The third, with Geraldo Rivera in 1988, was part of that journalist's prime-time special on Satanism.[16] At least as early as the Snyder interview, Manson's forehead bore a swastika, in the spot where the X carved during his trial had been.[17]

In 1989, Nikolas Schreck conducted an interview with Manson, cutting the interview up for material in his documentary Charles Manson Superstar. Schreck concluded that Manson was not insane, but merely acting that way out of frustration.[18][19]

On September 25, 1984, while imprisoned at the California Medical Facility at Vacaville, Manson was severely burned by a fellow inmate who poured paint thinner on him and set him alight. The other prisoner, Jan Holmstrom, explained that Manson had objected to his Hare Krishna chants and verbally threatened him. Despite suffering second- and third-degree burns on over 20 percent of his body, Manson recovered from his injuries.[2]: 497

In June 1997, Manson was found to have been trafficking in drugs by a prison disciplinary committee.[20] That August, he was moved from Corcoran State Prison to Pelican Bay State Prison.[20]

In a 1998–99 interview in Seconds magazine, Bobby Beausoleil rejected the view that Manson ordered him to kill Gary Hinman.[21] He stated that Manson did come to Hinman's house and slash Hinman with a sword. In a 1981 interview with Oui magazine, he denied this. Beausoleil stated that when he read about the Tate murders in the newspaper, "I wasn't even sure at that point – really, I had no idea who had done it until Manson's group were actually arrested for it. It had only crossed my mind and I had a premonition, perhaps. There was some little tickle in my mind that the killings might be connected with them ..." In the Oui magazine interview, he had stated, "When the Tate-LaBianca murders happened, I knew who had done it. I was fairly certain."[22]

2000s–2010s

On September 5, 2007, MSNBC aired The Mind of Manson, a complete version of a 1987 interview at California's San Quentin State Prison. The footage of the "unshackled, unapologetic, and unruly" Manson had been considered "so unbelievable" that only seven minutes of it had originally been broadcast on The Today Show, for which it had been recorded.[23]

In a January 2008 segment of the Discovery Channel's Most Evil, Barbara Hoyt said that the impression that she had accompanied Ruth Ann Moorehouse to Hawaii just to avoid testifying at Manson's trial was erroneous. Hoyt said she had cooperated with the Family because she was "trying to keep them from killing my family." She stated that, at the time of the trial, she was "constantly being threatened: 'Your family's gonna die. [The murders] could be repeated at your house.'"[24]

On March 15, 2008, the Associated Press reported that forensic investigators had conducted a search for human remains at Barker Ranch the previous month. Following up on longstanding rumors that the Family had killed hitchhikers and runaways who had come into its orbit during its time at Barker, the investigators identified "two likely clandestine grave sites ... and one additional site that merits further investigation."[25] Though they recommended digging, CNN reported on March 28 that the Inyo County sheriff, who questioned the methods they employed with search dogs, had ordered additional tests before any excavation.[26] On 9 May, after a delay caused by damage to test equipment,[27] the sheriff announced that test results had been inconclusive and that "exploratory excavation" would begin on 20 May.[28] In the meantime, Charles "Tex" Watson had commented publicly that "no one was killed" at the desert camp during the month-and-a-half he was there, after the Tate-LaBianca murders.[29][30] On 21 May, after two days of work, the sheriff brought the search to an end; four potential gravesites had been dug up and had been found to hold no human remains.[31][32] In March 2009, a photograph taken of a 74-year-old Manson, showing a receding hairline, grizzled gray beard and hair and the swastika tattoo still prominent on his forehead, was released to the public by California corrections officials.[33]

In November 2009, a Los Angeles DJ and songwriter named Matthew Roberts released correspondence and other evidence indicating he may have been biologically fathered by Manson. Roberts' biological mother claims to have been a member of the Manson Family who left in the summer of 1967 after being raped by Manson; she returned to her parents' home to complete the pregnancy, gave birth on March 22, 1968, and subsequently put Roberts up for adoption. Manson himself has stated that he "could" be the father, acknowledging the biological mother and a sexual relationship with her during 1967; this was nearly two years before the Family began its murderous phase.[34][35]

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times reported that Manson was caught with a cell phone in 2009, and had contacted people in California, New Jersey, Florida and British Columbia. A spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections stated that it was not known if Manson had used the phone for criminal purposes.[36]

On November 17, 2014, it was announced that Manson was engaged to 26-year-old Afton Elaine "Star" Burton while still in prison, and had obtained a marriage license on November 7.[37] Burton had been visiting Manson in prison for at least nine years, and maintained several websites that claimed his innocence.[38] The wedding license expired on February 5, 2015, without a marriage ceremony taking place.[39] It was later reported that, according to journalist Daniel Simone, the wedding was cancelled after it was discovered that Burton only wanted to marry Manson so she and a friend, Craig "Gray Wolf" Hammond, could use his corpse as a tourist attraction after his death.[39][40] According to Simone, Manson believes he will never die, and may just be using the possibility of marriage as a way to encourage Burton and Hammond to continue visiting him and bringing him gifts.[39] Together with a co-author Heidi Jordan Ley and with the assistance of some of Manson's fellow prisoners, Simone has written a book about Manson and is seeking a publisher for it.[39] Burton said on her web site that the reason the marriage did not take place is merely logistical – that Manson is suffering from an infection and has been in a prison medical facility for two months, and cannot receive visitors.[39] She said she still hoped the marriage license will be renewed and the marriage will take place.[39]

On January 1, 2017, Manson was rushed from California State Prison, Corcoran, to Mercy Hospital in downtown Bakersfield suffering from gastrointestinal bleeding. A source told the Los Angeles Times Manson was seriously ill. [41] Some reports suggest Manson was too weak for surgery.[42] He was returned to prison by January 6; any treatment he had received was not disclosed.[43]

Parole hearings

A footnote to the conclusion of California v. Anderson, the 1972 decision that neutralized California's death sentences, stated that, "any prisoner now under a sentence of death … may file a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the superior court inviting that court to modify its judgment to provide for the appropriate alternative punishment of life imprisonment or life imprisonment without possibility of parole specified by statute for the crime for which he was sentenced to death."[44]

This made Manson eligible to apply for parole after seven years' incarceration.[2]: 488 Accordingly, his first parole hearing took place on November 16, 1978, at California Medical Facility in Vacaville, and his petition was rejected.[2]: 498 [45]

Manson was denied parole for the 12th time on April 11, 2012. Manson did not attend the hearing. In fact, the last parole hearing he had attended was March 27, 1997. The panel noted at his April 2012 hearing that Manson had a "history of controlling behavior" and "mental health issues" including schizophrenia and paranoid delusional disorder and was too great a danger to be released.[46] The panel also noted that Manson had received 108 rules violation reports, has no indication of remorse, no insight into the causative factors of the crimes, lacks understanding of the magnitude of the crimes, has an exceptional, callous disregard for human suffering and has no parole plans. [47] It was determined that Manson would not be reconsidered for parole for another 15 years, i.e. not before 2027,[48] at which time he would be 92 years old.

On October 4, 2012, Bruce Davis, who had been convicted of the murder of Shorty Shea and the attempted robbery by Manson Family members of a Hawthorne gun shop in 1971, was recommended for parole by the California Department of Corrections' parole board at his 27th parole hearing. In 2010, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger had reversed the board's previous finding in favor of Davis, denying him parole for two more years.[49] On March 1, 2013, and again on August 8, 2014, Governor Jerry Brown also denied parole for Davis.[50], as he did again on June 23, 2017.[51]

In July 2016, former Manson follower Leslie Van Houten's petition for parole was endorsed by the parole board and forwarded to California governor Jerry Brown who rejected it.[52]

Legacy

Recordings

On March 6, 1970, the day the court vacated Manson's status as his own attorney,[2]: 258–269 LIE, an album of Manson music, was released.[53][54][55] This included "Cease to Exist", a Manson composition the Beach Boys had recorded with modified lyrics and the title "Never Learn Not to Love".[56][57] Over the next couple of months, only about 300 of the album's 2,000 copies sold.[58]

Since that time, there have been several releases of Manson recordings – both musical and spoken.[59] One of these, The Family Jams, includes two compact discs of Manson's songs recorded by the Family in 1970, after Manson and the others had been arrested. Guitar and lead vocals are supplied by Steve Grogan;[2]: 125–127 additional vocals are supplied by Lynette Fromme, Sandra Good, Catherine Share, and others.[59][60] One Mind, an album of music, poetry, and spoken word, new at the time of its release, in April 2005,[59] was put out under a Creative Commons license.[61][62]

American rock band Guns N' Roses recorded Manson's "Look at Your Game, Girl", included as an unlisted 13th track on their 1993 album "The Spaghetti Incident?"[2]: 488–491 [63][64] "My Monkey", which appears on Portrait of an American Family by Marilyn Manson (no relation, as is explained below), includes the lyrics "I had a little monkey / I sent him to the country and I fed him on gingerbread / Along came a choo-choo / Knocked my monkey cuckoo / And now my monkey's dead."[65] These lyrics are from Manson's "Mechanical Man",[66] which is heard on LIE. Crispin Glover covered "Never Say 'Never' To Always" on his album The Big Problem ≠ The Solution. The Solution = Let It Be released in 1989. Transgressive punk rock performance artist GG Allin covered "Garbage Dump" (from LIE) on his album You Give Love A Bad Name.

Several of Manson's songs, including "I'm Scratching Peace Symbols on Your Tombstone" (a.k.a. "First They Made Me Sleep in the Closet"), "Garbage Dump", and "I Can't Remember When", are featured in the soundtrack of the 1976 TV-movie Helter Skelter, where they are performed by Steve Railsback, who portrays Manson.

According to a popular urban legend, Manson unsuccessfully auditioned for the Monkees in late 1965; this is refuted by the fact that Manson was still incarcerated at McNeil Island at that time.[67]

Cultural influence

Beginning in January 1970, Manson was embraced by the underground newspapers Los Angeles Free Press and Tuesday's Child, with the latter proclaiming him "Man of the Year."[68] In June 1970, he was the subject of a Rolling Stone cover story, "Charles Manson: The Incredible Story of the Most Dangerous Man Alive."[68] When a Rolling Stone writer visited the Los Angeles District Attorney's office in preparing that story,[69] he was shocked by a photograph of the bloody "Healter [sic] Skelter" that would bind Manson to popular culture.[70] Bugliosi pointed out the dispute in the underground press over whether Manson was "Christ returned" or "a sick symbol of our times"[where?] to his Helter Skelter co-author, Curt Gentry.

Bernardine Dohrn, a leader of the Weather Underground reportedly said about the Tate murders: "Dig it, first they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, then they even shoved a fork into a victim's stomach. Wild!"[71]

Manson has been a presence in fashion,[72][73] graphics,[74][75] music,[76] and movies, as well as on television and the stage. In an afterword composed for the 1994 edition of the non-fiction book Helter Skelter, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi quoted a BBC employee's assertion that a "neo-Manson cult" existing then in Europe was represented by, among other things, approximately 70 rock bands playing songs by Manson and "songs in support of him".[2]: 488–491

Manson has even influenced the names of musical performers such as Kasabian, Spahn Ranch, and Marilyn Manson, the last a stage name which Brian Warner (his real name) assembled from "Charles Manson" and "Marilyn Monroe." The story of the Family's activities inspired John Moran's opera The Manson Family and Stephen Sondheim's musical Assassins, the latter of which has Lynette Fromme as a character.[77][78] The tale has been the subject of several movies such as the 1984 film Manson Family Movies,[79] including two television dramatizations of Helter Skelter. In the South Park episode "Merry Christmas, Charlie Manson," Manson is a comical character whose inmate number is 06660, an apparent reference to 666, the Biblical "number of the beast."[80][81]

The 2002 novel The Dead Circus by John Kaye includes the activities of the Manson Family as a major plot point.[82]

In 2015, J. Davis released the American indie comedy Manson Family Vacation portraying two brothers traveling through to California, retracing Manson's steps. The movie deals with Manson present-day followers such as Grey Wolf. The movie was independently released and later released on Netflix.

In 2015, NBC premiered the crime drama Aquarius, with Gethin Anthony playing Manson. The series was set in 1967 and included storylines that were inspired by actual events which involved Manson.[83]

Documentaries

- Manson (1973), directed by Robert Hendrickson and Laurence Merrick

- Charles Manson Superstar (1989), directed by Nikolas Schreck

- Life After Manson (2014), directed by Olivia Klaus

See also

- Doomsday cult

- Helter Skelter (Manson scenario)

- Trials of the Century

- List of United States death row inmates

References

Notes

- ^ Johnson, Bruce; Martin Cloonan (2013). Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence. Ashgate. p. 83. ISBN 1-4094-9392-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Bugliosi, Vincent with Gentry, Curt. Helter Skelter – The True Story of the Manson Murders 25th Anniversary Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-393-08700-X. oclc=15164618.

- ^ "Internet Accuracy Project: Charles Manson, a website dedicated to providing accurate information on the web". Accuracyproject.org. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Emmons, Nuel. Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press, New York; 1988. ISBN 0-8021-3024-0, p. 28. (If link does not go directly to page 28, scroll to it; "no name Maddox" is highlighted.)

- ^ a b Smith, Dave. Mother Tells Life of Manson as Boy. 1971 article; retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ Reitwiesner, William Addams. Provisional ancestry of Charles Manson; retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Photocopy of Manson birth certificate Archived August 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine MansonDirect.com; retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ "Internet Accuracy Project: Charles Manson". Accuracyproject.org. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Emmons, Nuel. Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press, New York (1988); ISBN 0-8021-3024-0, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c d Emmons, Nuel. Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press, New York (1988); ISBN 0-8021-3024-0

- ^ "Long Before Little Charlie Became the Face of Evil". The New York Times. August 7, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Short Bits 2 – Charles Manson and the Beach Boys". Lost in the Grooves. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ Rule, Ann (August 18, 2013). "There Will Be Blood". The New York Times Book Review (August 18, 2013): 14.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 1981 Tom Snyder interview with Charles Manson Part 1 through 7. OneMansBlog.com. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Joynt, Carol. Diary of a Mad Saloon Owner Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. April–May 2005.

- ^ "Rivera's 'Devil Worship' was TV at its Worst." Review by Tom Shales. San Jose Mercury News, October 31, 1988.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (July 31, 2007). "Hearts and Souls Dissected, in 12 Minutes or Less". New York Times. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Appraisal of Tom Snyder, upon his death. Includes photograph of Manson with swastika on forehead during 1981 interview.

- ^ Charles Manson Superstar, 1989.

- ^ Interano Radio "Interview with Nikolas Schreck," August 1988.

- ^ a b "Manson moved to a tougher prison after drug charge". Sun Journal. Lewiston, Maine. AP. August 22, 1997. p. 7A. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "Beausoleil Seconds interviews". beausoleil.net. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Beausoleil Oui interview". charliemanson.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Transcript, MSNBC Live. September 5, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ "Charles Manson Murders". Most Evil. Season 3. Episode 1. January 31, 2008. Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "AP Exclusive: On Manson's trail, forensic testing suggests possible new grave sites". Archived March 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ More tests at Manson ranch for buried bodies. CNN.com. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Authorities delay decision on digging at Manson ranch Associated Press report, mercurynews.com. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Authorities to dig at old Manson family ranch cnn.com. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Letter from Manson lieutenant. CNN. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Monthly View – May 2008. Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Aboundinglove.org. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Four holes dug, no bodies found ... Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine iht.com. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ Dig turns up no bodies at Manson ranch site CNN.com, May 21, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ "New prison photo of Charles Manson released". CNN. March 20, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ Borland, Huw, "Man Finds His Long-Lost Dad Is Charles Manson Archived November 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine http://news.sky.com/story/1100003/youngest-manson-family-member-denied-parole",, Sky News Online, November 23, 2009. http://news.sky.com/story/1100003/youngest-manson-family-member-denied-parole

- ^ Samson, Peter, "I traced my dad ... and discovered he is Charles Manson", The Sun, November 23, 2009 (membership required for access).

- ^ Wilson, Greg (December 3, 2010). ""Cell" Phone: Charles Manson Busted with a Mobile". Nbclosangeles.com. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ 5 Things to Know About the 26-Year-Old Woman Charles Manson Might Marry time.com. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Deutsch, Linda. "Charles Manson Gets Marriage License". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Sanderson, Bill (February 8, 2015). "Charles Manson's fiancee wanted to marry him for his corpse: Source". The New York Post. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Hooton, Christopher (February 9, 2015). "Charles Manson wedding off after it emerges that fiancee Afton Elaine Burton 'just wanted his corpse for display'". The Independent. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Hamilton, Matt; Branson-Potts, Hailey (January 4, 2017). "Killer Charles Manson's failing health renews focus on cult murder saga". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "US killer Manson 'too weak' for surgery". RTÉ. January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Christensen, Kim (January 7, 2017). "Charles Manson is returned to prison after stay at Bakersfield hospital". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ People v. Anderson, 493 P.2d 880, 6 Cal. 3d 628 (Cal. 1972), footnote (45) to final sentence of majority opinion. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ "Charles Manson Family and Sharon Tate-Labianca Murders – Cielodrive.com". Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Charles Manson Quickly Denied Parole". LA Times. April 11, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ http://cielodrive.com/charles-manson-parole-hearing-2012.php

- ^ Jones, Kiki (April 11, 2012). "Murderer Charles Manson Denied Parole – Central Coast News KION/KCBA". Kionrightnow.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)http://www.pressherald.com/2012/04/11/manson-skips-12th-parole-hearing-may-be-his-last/ - ^ "Bruce Davis, Manson Follower, Gets Cleared For Release By California Parole Board". Huffingtonpost.com. October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "Governor denies parole to ex-Manson follower". seattlepi. Retrieved March 1, 2013.[dead link]https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/03/01/bruce-davis-manson-release-denied/1957737/

- ^ Jacey Fortin, "Bruce Davis, a Charles Manson Follower, Has Parole Blocked for Fifth Time", The New York Times, June 24, 2017

- ^ "California Governor Denies Parole for Manson Ex-Follower Leslie Van Houten", NBC, July 23, 2016

- ^ Sanders 2002, 336.

- ^ Lie: The Love And Terror Cult Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. ASIN: B000005X1J. Amazon.com. Access date: November 23, 2007.

- ^ Syndicated column re LIE release Mike Jahn, August 1970.

- ^ Sanders 2002, 64–65.

- ^ Dennis Wilson interview Circus magazine, October 26, 1976. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ Rolling Stone story on Manson, June 1970 Archived November 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine https://www.rollingstone.com/coverwall/1970 CharlieManson.com. Retrieved May 2, 2007. https://www.rollingstone.com/coverwall/1970

- ^ a b c List of Manson recordings mansondirect.com. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ The Family Jams. ASIN: B0002UXM2Q. 2004. Amazon.com.

- ^ Charles Manson Issues Album under Creative Commons pcmag.com. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ Yes it's CC! Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Photo verifying Creative Commons license of One Mind. blog.limewire.com. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ Review of The Spaghetti Incident? allmusic.com. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Guns N' Roses Biography http://www.themusichype.com/guns-n-roses-biography/ themusichype.com. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Manson related music." Archived August 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine charliemanson.com. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Lyrics of "Mechanical Man" Archived August 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine http://www.lyricsmania.com/mechanical_man_lyrics_charles_manson.html charliemanson.com. Retrieved January 22, 2008. http://www.lyricsmania.com/mechanical_man_lyrics_charles_manson.html

- ^ "The Music Manson." snopes.com. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Charles Manson: The Incredible Story of the Most Dangerous Man Alive rollingstone.com. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ Manson on cover of Rolling Stone Archived April 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine rollingstone.com. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ Dalton, David. If Christ Came Back as a Con Man. [1] gadflyonline.com. Retrieved September 30, 2007. Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Seeds of Terror". The New York Times. November 22, 1981. p. 5. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Bant Shirts Manson T-shirt". Bant-shirts.com. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "Prank Place Manson T-shirt". Prankplace.com. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "No Name Maddox" Archived November 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Manson portrait in marijuana seeds. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Poster of Manson on cover of Rolling Stone Archived August 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Manson-related music Archived August 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine charliemanson.com. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "Will the Manson Story Play as Myth, Operatically at That?" New York Times. July 17, 1990. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ "Assassins". Sondheim.com. November 22, 1963. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ David Kerekes, David Slater (1996). Killing for Culture. Creation Books. pp. 222–223, 225, 268. ISBN 1-871592-20-8. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Merry Christmas Charlie Manson http://shop.southparkstudios.com/Christmas-Time-In-South-Park/A/B000UAE7UE.htm Video clips at southpark.comedycentral.com Archived August 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Beast Number WolframMathWorld. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- ^ Stephanie Zacharek (August 18, 2002). "Bad Vibrations". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Aquarius Official Website NBC

Bibliography

- Atkins, Susan with Bob Slosser. Child of Satan, Child of God. Logos International; Plainfield, New Jersey; 1977. ISBN 0-88270-276-9.

- Bugliosi, Vincent with Curt Gentry. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders. (Norton, 1974; Arrow books, 1992 edition, ISBN 0-09-997500-9; W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, ISBN 0-393-32223-8)

- Emmons, Nuel, as told to. Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8021-3024-0.

- Sanders, Ed The Family. Thunder's Mouth Press. rev. update edition 2002. ISBN 1-56025-396-7.

- Watkins, Paul with Guillermo Soledad. My Life with Charles Manson. Bantam, 1979. ISBN 0-553-12788-8.

- Watson, Charles. Will you die for me?. F. H. Revell, 1978. ISBN 0-8007-0912-8.

Further reading

- George, Edward and Dary Matera. Taming the Beast: Charles Manson's Life Behind Bars. St. Martin's Press, 1999. ISBN 0-312-20970-3.

- Emmons, Nuel. Manson in his Own Words. Grove Press. 1994. ISBN 0-8021-3024-0

- Gilmore, John. Manson: The Unholy Trail of Charlie and the Family. Amok Books, 2000. ISBN 1-878923-13-7.

- Gilmore, John. The Garbage People. Omega Press, 1971.

- Guinn, Jeff. Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. Simon & Schuster, 2013. ISBN 1451645163

- LeBlanc, Jerry and Ivor Davis. 5 to Die. Holloway House Publishing, 1971. ISBN 0-87067-306-8.

- Pellowski, Michael J. The Charles Manson Murder Trial: A Headline Court Case. Enslow Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-7660-2167-X.

- Schreck, Nikolas. The Manson File Amok Press. 1988. ISBN 0-941693-04-X.

- Schreck, Nikolas. The Manson File, Myth and Reality of an Outlaw Shaman World Operations. 2011. ISBN 978-3-8442-1094-1

- Udo, Tommy. Charles Manson: Music, Mayhem, Murder. Sanctuary Records, 2002. ISBN 1-86074-388-9.

External links

- Dalton, David. If Christ Came Back as a Con Man http://www.gadflyonline.com/archive/october98/archive-manson.html. 1998 article by coauthor of 1970 Rolling Stone story on Manson. gadflyonline.com. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- Linder, Douglas. Famous Trials – The Trial of Charles Manson. University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School. 2002. April 7, 2007.

- Noe, Denise. "The Manson Myth" CrimeMagazine.com December 12, 2004

- FBI file on Charles Manson

- Decision in appeal by Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten from Tate-LaBianca convictionsPeople v. Manson, 61 Cal. App. 3d 102 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, August 13, 1976). Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- Decision in appeal by Manson from Hinman-Shea conviction People v. Manson, 71 Cal. App. 3d 1 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, June 23, 1977).

- Horrific past haunts former cult members San Francisco Chronicle August 12, 2009

- 20th-century American criminals

- 1934 births

- American folk rock musicians

- American people convicted of murder

- American prisoners and detainees

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American singer-songwriters

- Apocalypticists

- Criminals from California

- Criminals from Ohio

- Former Scientologists

- History of Los Angeles

- Living people

- Manson Family

- Outsider musicians

- People associated with the Beach Boys

- People convicted of murder by California

- People from Cincinnati

- People with antisocial personality disorder

- People with schizophrenia

- Prisoners sentenced to death by California

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by California

- Self-declared messiahs

- American people of German descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of English descent