User:PaleoGeekSquared/sandbox: Difference between revisions

Starting work on Spinosauridae GAN |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<!-- EDIT BELOW THIS LINE --> |

<!-- EDIT BELOW THIS LINE --> |

||

{{In use|a short while. A ''lot'' of new sections, information, and references will be added as well as multiple minor changes in order to prepare the article for a more in-depth [[Wikipedia:Good_articles|GA]] review. Visit the [[Talk:Spinosauridae/GA1|GAN talk page]] for more information}} |

|||

{{Automatic taxobox |

{{Automatic taxobox |

||

| name = Spinosaurids |

| name = Spinosaurids |

||

| Line 32: | Line 33: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Spinosauridae''' (meaning '[[Neural spine|spined]] lizards') is a [[Family (taxonomy)|family]] of [[Megalosauroidea|megalosauroidean]] [[theropod]] [[dinosaur]]s |

'''Spinosauridae''' (meaning '[[Neural spine|spined]] lizards') is a [[Family (taxonomy)|family]] of [[Megalosauroidea|megalosauroidean]] [[theropod]] [[dinosaur]]s, it contains the eponymous ''[[Spinosaurus]]'', which is currently one of if not the largest terrestrial [[Predation|predator]] known from the [[fossil record]], and might have measured up to 15 m (49 ft) in length.<ref name="Ibrahim_et_al_2014">{{cite journal|last1=Ibrahim|first1=Nizar|last2=Sereno|first2=Paul C.|last3=Dal Sasso|first3=Cristiano|last4=Maganuco|first4=Simone|last5=Fabri|first5=Matteo|last6=Martill|first6=David M.|last7=Zouhri|first7=Samir|last8=Myhrvold|first8=Nathan|last9=Lurino|first9=Dawid A.|date=2014|title=Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6204/1613.abstract|journal=Science|volume=345|issue=6204|pages=1613–6|bibcode=2014Sci...345.1613I|doi=10.1126/science.1258750|pmid=25213375}} [http://www.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2014/09/10/science.1258750.DC1/Ibrahim.SM.pdf Supplementary Information]</ref> Most spinosaurids lived during the [[Cretaceous period]], and [[fossil]]s of them have been recovered worldwide, including [[Africa]], [[Europe]], [[South America]], [[Asia]] and [[Australia]]. |

||

They were large [[Bipedalism|bipedal]] [[Carnivore|carnivores]] with elongated, [[crocodile]]-like [[Skull|skulls]], sporting conical teeth with no or only very tiny [[Serration|serrations]]. The teeth in the front end of the lower jaw |

They were large [[Bipedalism|bipedal]] [[Carnivore|carnivores]] with elongated, [[crocodile]]-like [[Skull|skulls]], sporting conical teeth with no or only very tiny [[Serration|serrations]], and oftentimes small [[Sagittal crest|crests]] on top of their heads. The teeth in the front end of the lower jaw fanned out into a structure called a [[Rosette (design)|rosette]], which gave the animal a characteristic look. Their shoulder blades were robust and hook-shaped, bearing relatively large forelimbs with enlarged claws on the first digit of their hands. Some genera also had unusually elongated [[neural spines]], which might have supported [[Neural spine sail|sails]] or humps made of skin and fat tissue. |

||

[[Sediment]] analysis has revealed that most spinosaurids inhabited [[Fresh water|fresh]]-to-[[Brackish water|brackish]] shallow water habitats in [[Tropics|tropical]] regions, often near [[Lagoon|lagoons]], [[Marsh|marshes]], and [[Mudflat|mudflats.]] These environments would have been optimal for a [[List of semiaquatic tetrapods|semi-aquatic]] lifestyle, which has also been corroborated by [[isotope]] and [[osteological]] (bone) analyses done on several taxa in this clade. Coupled with their conical teeth, designed for gripping prey instead of ripping flesh, this would have made them [[Specialist (biology)|specialists]], hunting mostly [[fish]], while feeding opportunistically on other animals. |

|||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

| Line 44: | Line 47: | ||

==== Dorsal sails ==== |

==== Dorsal sails ==== |

||

''[[Spinosaurus Aegyptiacus|Spinosaurus aegyptiacus]]'', the type species for the family and [[subfamily]], is known for the vertebrae with [[Neural spine sail|elongated neural spines]], some over a meter tall, which have been reconstructed as a [[Dorsal sail|sail]] or hump running down its back.<ref name="Hecht1998">Hecht, Jeff. 1998. “Fish Swam in Fear.” New Scientist. November 21. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg16021610-300-fish-swam-in-fear/. |

''[[Spinosaurus Aegyptiacus|Spinosaurus aegyptiacus]]'', the type species for the family and [[subfamily]], is known for the vertebrae with [[Neural spine sail|elongated neural spines]], some over a meter tall, which have been reconstructed as a [[Dorsal sail|sail]] or hump running down its back.<ref name="Hecht1998">Hecht, Jeff. 1998. “Fish Swam in Fear.” New Scientist. November 21. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg16021610-300-fish-swam-in-fear/. |

||

</ref> [[File:Spinosauridae_"Sails"_Comparison_by_PaleoGeek.png|thumb|left|180px|Variation of neural spines in 3 different spinosaurid species]] In ''[[Ichthyovenator]],'' this sail is a half a meter at its highest and split into two at the [[Sacral vertebra|sacral]] vertebrae.<ref name="AXRK12">{{Cite journal|last1=Allain|first1=R.|last2=Xaisanavong|first2=T.|last3=Richir|first3=P.|last4=Khentavong|first4=B.|year=2012|title=The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos|journal=Naturwissenschaften|volume=99|issue=5|pages=369–377|bibcode=2012NW.....99..369A|doi=10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7|pmc=|pmid=22528021}}</ref> ''[[Suchomimus]]'' also has a low, ridge-like sail over its hips, smaller than that of ''Spinosaurus''.<ref name="Hecht1998" /> [[Baryonyx|''Baryonyx'']], however, lacks a sail.<ref name="charigmilner19972">{{Cite journal|last=Charig|first=A. J.|last2=Milner|first2=A. C.|year=1997|title=''Baryonyx walkeri'', a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey|url=http://biostor.org/reference/110558|journal=Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London|series=|volume=53|pages=11–70}}</ref> Because of [[phylogenetic bracketing]], other spinosaurids such as ''Irritator'' might have also had extended neural spines, but sufficient fossil vertebra are needed to know for certain. |

|||

| ⚫ | These structures have had many proposed functions over the years, such as [[thermoregulation]],<ref name="LBH75">{{cite book|title=The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs|last=Halstead|first=L.B.|publisher=Eurobook Limited|year=1975|isbn=0-85654-018-8|location=London|pages=1–116|authorlink=Beverly Halstead}}</ref> to aid in swimming,<ref name=":0" /> to store energy or insulate the animal, or for display purposes, such as intimidating rivals and predators, or attracting mates.<ref name="JBB972">{{cite journal|last=Bailey|first=J.B.|year=1997|title=Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=71|issue=6|pages=1124–1146|jstor=1306608}}</ref><ref name="Stromer15" /> |

||

==== Bony crests ==== |

==== Bony crests ==== |

||

Another feature that makes spinosaurid skulls unique from most other theropods, is that they often feature relatively large [[Sagittal crest|sagittal crests]] formed from their [[Nasal bone|nasal bones]]. These crests have been present in ''Spinosaurus'' as a ridge-shaped structure, and in ''Suchomimus'' and ''Baryonyx'' as smaller bumps on top of the skull.<ref name="charigmilner1997">{{Cite journal|last=Charig|first=A. J.|last2=Milner|first2=A. C.|year=1997|title=''Baryonyx walkeri'', a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey|url=http://biostor.org/reference/110558|journal=Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London|series=|volume=53|pages=11–70}}</ref> They have also been seen (to a smaller degree) in ,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Sues|first1=H. D.|last2=Frey|first2=E.|last3=Martill|first3=D. M.|last4=Scott|first4=D. M.|year=2002|title=Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=22|issue=3|pages=535–547|doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> and ''[[Cristatusaurus]]''.<ref name="TaquetRussell">Taquet, P. and Russell, D.A. (1998). "New data on spinosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of the Sahara". ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes'' 327: 347-353</ref> |

Another feature that makes spinosaurid skulls unique from most other theropods, is that they often feature relatively large [[Sagittal crest|sagittal crests]] formed from their [[Nasal bone|nasal bones]]. These crests have been present in ''Spinosaurus'' as a ridge-shaped structure, and in ''Suchomimus'' and ''Baryonyx'' as smaller bumps on top of the skull.<ref name="charigmilner1997">{{Cite journal|last=Charig|first=A. J.|last2=Milner|first2=A. C.|year=1997|title=''Baryonyx walkeri'', a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey|url=http://biostor.org/reference/110558|journal=Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London|series=|volume=53|pages=11–70}}</ref> They have also been seen (to a smaller degree) in ,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Sues|first1=H. D.|last2=Frey|first2=E.|last3=Martill|first3=D. M.|last4=Scott|first4=D. M.|year=2002|title=Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=22|issue=3|pages=535–547|doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> and ''[[Cristatusaurus]]''.<ref name="TaquetRussell">Taquet, P. and Russell, D.A. (1998). "New data on spinosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of the Sahara". ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes'' 327: 347-353</ref> |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

=== Phylogeny === |

=== Phylogeny === |

||

The subfamily Spinosaurinae was named by Sereno in 1998, and defined by [[Thomas R. Holtz Jr.|Holtz]] ''et al.'' (2004) as all [[taxa]] closer to ''Spinosaurus aegyptiacus'' than to ''Baryonyx walkeri''. And the subfamily Baryonychinae was named by [[Alan J. Charig|Charig]] & [[Angela C. Milner|Milner]] in 1986. They erected both the subfamily and the family Baryonychinae for the newly discovered ''Baryonyx'', before it was referred to the Spinosauridae. Their subfamily was defined by Holtz ''et al.'' in 2004, as the complementary clade of all taxa closer to ''Baryonyx walkeri'' than to ''Spinosaurus aegyptiacus''. Examinations by Marcos Sales and Cesar Schultz ''et al.'' indicate that the South American spinosaurids ''Angaturama'', ''Irritator'', and ''Oxalaia'' were intermediate between Baronychinae and Spinosaurinae based on their craniodental features and cladistic analysis. This indicates that Baryonychinae may in fact be non-monophyletic. Their [[cladogram]] can be seen below.<ref name="salesschultz"/> |

The subfamily Spinosaurinae was named by Sereno in 1998, and defined by [[Thomas R. Holtz Jr.|Holtz]] ''et al.'' (2004) as all [[taxa]] closer to ''Spinosaurus aegyptiacus'' than to ''Baryonyx walkeri''. And the subfamily Baryonychinae was named by [[Alan J. Charig|Charig]] & [[Angela C. Milner|Milner]] in 1986. They erected both the subfamily and the family Baryonychinae for the newly discovered ''Baryonyx'', before it was referred to the Spinosauridae. Their subfamily was defined by Holtz ''et al.'' in 2004, as the complementary clade of all taxa closer to ''Baryonyx walkeri'' than to ''Spinosaurus aegyptiacus''. Examinations by Marcos Sales and Cesar Schultz ''et al.'' indicate that the South American spinosaurids ''Angaturama'', ''Irritator'', and ''Oxalaia'' were intermediate between Baronychinae and Spinosaurinae based on their craniodental features and cladistic analysis. This indicates that Baryonychinae may in fact be non-monophyletic. Their [[cladogram]] can be seen below.<ref name="salesschultz"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{clade| style=font-size:85%; line-height:85% |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

|1=''[[Condorraptor]]'' [[File:Condorraptor (Flipped).jpg|50px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|2=''[[Marshosaurus]]'' [[File:Marshosaurus restoration.jpg|80px]] |

|||

|1=''[[Baryonyx]]''[[File:Baryonyx_walkeri_restoration.jpg|80px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

|3=''[[Suchomimus]]''[[File:Suchomimustenerensis_(Flipped).png|80px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|2=''[[Dubreuillosaurus]]'' [[File:Dubreuillosaurus NT Flipped.png|80px]] |

|||

| |

|1=''[[Angaturama]]''[[File:Irritator_Life_Reconstruction.jpg|80px]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

|4=''[[Eustreptospondylus]]'' [[File:Eustrept1DB1 (Flipped).jpg|80px]] |

|||

| |

|1='''''Oxalaia''''' |

||

| |

|2=''[[Spinosaurus]]'' [[File:Spinosaurus by Joschua Knüppe.png|80px]] }} }} }} }} |

||

|7=''[[Megalosaurus]]'' [[File:Megalosaurus silhouette by Paleogeek.svg|80px]] |

|||

|8=''[[Piveteausaurus]]'' |

|||

|9=''[[Torvosaurus]]'' [[File:Torvosaurus tanneri Reconstruction (Flipped).png|80px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|10={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Baryonyx]]'' [[File:Baryonyx_walkeri_restoration.jpg|80px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|3=''[[Suchomimus]]''[[File:Suchomimustenerensis_(Flipped).png|80px]] |

|||

|4={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Angaturama]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Oxalaia]]'' |

|||

|2=MSNM V4047 (referred to ''[[Spinosaurus]]'') [[File:Spinosaurus by Joschua Knüppe.png|80px]] }} }} }} }} }}|style=font-size:85%; line-height:85%|label1=[[Megalosauroidea]]}} |

|||

The next cladogram displays an analysis of [[Tetanurae]] simplified to show only Spinosauridae from Allain <i>et al.</i> (2012):<ref name="AXRK122">{{Cite journal|last1=Allain|first1=R.|last2=Xaisanavong|first2=T.|last3=Richir|first3=P.|last4=Khentavong|first4=B.|year=2012|title=The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos|journal=Naturwissenschaften|volume=99|issue=5|pages=369–377|bibcode=2012NW.....99..369A|doi=10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7|pmc=|pmid=22528021}}</ref>{{clade|{{clade |

The next cladogram displays an analysis of [[Tetanurae]] simplified to show only Spinosauridae from Allain <i>et al.</i> (2012):<ref name="AXRK122">{{Cite journal|last1=Allain|first1=R.|last2=Xaisanavong|first2=T.|last3=Richir|first3=P.|last4=Khentavong|first4=B.|year=2012|title=The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos|journal=Naturwissenschaften|volume=99|issue=5|pages=369–377|bibcode=2012NW.....99..369A|doi=10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7|pmc=|pmid=22528021}}</ref>{{clade|{{clade |

||

|label1=[[Spinosaurinae]] |

|label1=[[Spinosaurinae]] |

||

| Line 122: | Line 110: | ||

==Paleobiology== |

==Paleobiology== |

||

===Lifestyle and hunting=== |

===Lifestyle and hunting=== |

||

====Teeth==== |

|||

[[File:Baryonyx_BW.jpg|thumb|right|Life restoration of ''Baryonyx'' with a fish in its jaws]] |

[[File:Baryonyx_BW.jpg|thumb|right|Life restoration of ''Baryonyx'' with a fish in its jaws]] |

||

Spinosaurid teeth resemble those of crocodiles, which are used for piercing and holding prey. Therefore, teeth with small or no serrations, such as in spinosaurids, were not good for cutting or ripping into flesh but instead to ensure a strong grip on a struggling prey animal.<ref name="suesetal2002">Sues, Hans-Dieter, Eberhard Frey, David M. Martill, and Diane M. Scott. 2002. “Irritator Challengeri, a Spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 535–47. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.</ref> Spinosaur jaws were likened by Vullo ''et al.'' to those of the [[pike conger eel]], in what they hypothesized was [[convergent evolution]] for aquatic feeding.<ref name=Vulloetal.2016>{{cite journal|last1=Vullo|first1=R.|last2=Allain|first2=R.|last3=Cavin|first3=L.|title=Convergent evolution of jaws between spinosaurid dinosaurs and pike conger eels|journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica|date=2016|volume=61|doi=10.4202/app.00284.2016}}</ref> Both kinds of animals have some teeth in the end of the upper and lower jaws that are larger than the others and an area of the upper jaw with smaller teeth, creating a gap into which the enlarged teeth of the lower jaw fit, with the full structure called a terminal rosette.<ref name="Vulloetal.2016" /> |

Spinosaurid teeth resemble those of crocodiles, which are used for piercing and holding prey. Therefore, teeth with small or no serrations, such as in spinosaurids, were not good for cutting or ripping into flesh but instead to ensure a strong grip on a struggling prey animal.<ref name="suesetal2002">Sues, Hans-Dieter, Eberhard Frey, David M. Martill, and Diane M. Scott. 2002. “Irritator Challengeri, a Spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 535–47. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.</ref> Spinosaur jaws were likened by Vullo ''et al.'' to those of the [[pike conger eel]], in what they hypothesized was [[convergent evolution]] for aquatic feeding.<ref name=Vulloetal.2016>{{cite journal|last1=Vullo|first1=R.|last2=Allain|first2=R.|last3=Cavin|first3=L.|title=Convergent evolution of jaws between spinosaurid dinosaurs and pike conger eels|journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica|date=2016|volume=61|doi=10.4202/app.00284.2016}}</ref> Both kinds of animals have some teeth in the end of the upper and lower jaws that are larger than the others and an area of the upper jaw with smaller teeth, creating a gap into which the enlarged teeth of the lower jaw fit, with the full structure called a terminal rosette.<ref name="Vulloetal.2016" />[[File:Spinosaurus_skull_en.svg|thumb|right|Annotated skull diagram of ''Spinosaurus'']] |

||

====Skull==== |

|||

[[File:Spinosaurus_skull_en.svg|thumb|right|Annotated skull diagram of ''Spinosaurus'']] |

|||

Spinosaurids have in the past often been considered mainly fish-eaters ([[Piscivore|piscivores]]), based on comparisons of their jaws with those of modern [[Crocodilia|crocodilians]].<ref name=Rayfield2011>Rayfield, Emily J. 2011. “Structural Performance of Tetanuran Theropod Skulls, with Emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae.” Special Papers in Palaeontology 86 (November). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250916680_Structural_performance_of_tetanuran_theropod_skulls_with_emphasis_on_the_Megalosauridae_Spinosauridae_and_Carcharodontosauridae.</ref> Rayfield and colleagues, in 2007, conducted biomechanical studies on the skull of the European spinosaurid ''Baryonyx'', which has a long, laterally compressed skull, comparing it to [[gharial]] (long, narrow, tubular) and [[alligator]] (flat and wide) skulls.<ref name="rayfieldetal2007">Rayfield, Emily J., Angela C. Milner, Viet Bui Xuan, and Philippe G. Young. 2007. “Functional Morphology of Spinosaur ‘crocodile-Mimic’ Dinosaurs.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 892–901. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[892:FMOSCD]2.0.CO;2.</ref> They found that the structure of baryonychine jaws converged on that of gharials, in that the two taxa showed similar response patterns to stress from simulated feeding loads, and did so with and without the presence of a (simulated) secondary palate. The gharial, exemplar of a long, narrow, and tubular snout, is a fish specialist. However, this snout anatomy doesn’t preclude other options for the spinosaurids. While the gharial is the most extreme example and a fish specialist, and [[Australian Freshwater Crocodile|Australian freshwater crocodiles]] (''Crocodylus johnstoni''), which have similarly shaped skulls to gharials, also specialize more on fish than sympatric, broad snouted crocodiles. And are opportunistic feeders which eat all manner of small aquatic prey, including [[Insect|insects]] and [[Crustacean|crustaceans]].<ref name="rayfieldetal2007" /> Thus, their aptly shaped snouts correlate with fish-eating, this is consistent with hypotheses of this diet for spinosaurids, in particular baryonychines, but it does not indicate that they were solely piscivorous. |

Spinosaurids have in the past often been considered mainly fish-eaters ([[Piscivore|piscivores]]), based on comparisons of their jaws with those of modern [[Crocodilia|crocodilians]].<ref name=Rayfield2011>Rayfield, Emily J. 2011. “Structural Performance of Tetanuran Theropod Skulls, with Emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae.” Special Papers in Palaeontology 86 (November). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250916680_Structural_performance_of_tetanuran_theropod_skulls_with_emphasis_on_the_Megalosauridae_Spinosauridae_and_Carcharodontosauridae.</ref> Rayfield and colleagues, in 2007, conducted biomechanical studies on the skull of the European spinosaurid ''Baryonyx'', which has a long, laterally compressed skull, comparing it to [[gharial]] (long, narrow, tubular) and [[alligator]] (flat and wide) skulls.<ref name="rayfieldetal2007">Rayfield, Emily J., Angela C. Milner, Viet Bui Xuan, and Philippe G. Young. 2007. “Functional Morphology of Spinosaur ‘crocodile-Mimic’ Dinosaurs.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 892–901. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[892:FMOSCD]2.0.CO;2.</ref> They found that the structure of baryonychine jaws converged on that of gharials, in that the two taxa showed similar response patterns to stress from simulated feeding loads, and did so with and without the presence of a (simulated) secondary palate. The gharial, exemplar of a long, narrow, and tubular snout, is a fish specialist. However, this snout anatomy doesn’t preclude other options for the spinosaurids. While the gharial is the most extreme example and a fish specialist, and [[Australian Freshwater Crocodile|Australian freshwater crocodiles]] (''Crocodylus johnstoni''), which have similarly shaped skulls to gharials, also specialize more on fish than sympatric, broad snouted crocodiles. And are opportunistic feeders which eat all manner of small aquatic prey, including [[Insect|insects]] and [[Crustacean|crustaceans]].<ref name="rayfieldetal2007" /> Thus, their aptly shaped snouts correlate with fish-eating, this is consistent with hypotheses of this diet for spinosaurids, in particular baryonychines, but it does not indicate that they were solely piscivorous. |

||

[[File:Spinosaurus_skull_steveoc.jpg|thumb|right|Life restoration of the head of ''Spinosaurus'']] |

[[File:Spinosaurus_skull_steveoc.jpg|thumb|right|Life restoration of the head of ''Spinosaurus'']] |

||

A further study by Cuff and Rayfield (2013) on the skulls of ''Spinosaurus'' and ''Baryonyx'' did not recover similarities in the skulls of ''Baryonyx'' and the gharial that the previous study did. ''Baryonyx'' had, in models where the size difference of the skulls was corrected for, greater resistance to torsion and dorsoventral bending than both ''Spinosaurus'' and the gharial, while both spinosaurids were inferior to the gharial, alligator, and [[slender-snouted crocodile]] in resisting torsion and medio-lateral bending.<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013>Cuff, Andrew R., and Emily J. Rayfield. 2013. “Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians.” PLOS ONE 8 (5): e65295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065295.</ref> When the results from the modeling were not scaled according to size, then both spinosaurids performed better than all the crocodilians in resistance to bending and torsion, due to their larger size.<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013 /> Thus, Cuff and Rayfield suggest that the skulls are not efficiently built to deal well with relatively large, struggling prey, but that the spinosaurids may overcome prey simply by their size advantage, and not skull build<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013 /> Sues and colleagues studied the construction of the spinosaurid skull, and concluded that their mode of feeding was to use extremely quick, powerful strikes to seize small prey items using their jaws, whilst employing the powerful neck muscles in rapid up-and-down motion. Due to the narrow snout, vigorous side-to-side motion of the skull during prey capture is unlikely.<ref name="suesetal2002" /> Based the size and positions of their nostrils, Sales & Schultz (2017) suggested that ''Spinosaurus'' possessed a greater reliance on its sense of smell and |

A further study by Cuff and Rayfield (2013) on the skulls of ''Spinosaurus'' and ''Baryonyx'' did not recover similarities in the skulls of ''Baryonyx'' and the gharial that the previous study did. ''Baryonyx'' had, in models where the size difference of the skulls was corrected for, greater resistance to torsion and dorsoventral bending than both ''Spinosaurus'' and the gharial, while both spinosaurids were inferior to the gharial, alligator, and [[slender-snouted crocodile]] in resisting torsion and medio-lateral bending.<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013>Cuff, Andrew R., and Emily J. Rayfield. 2013. “Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians.” PLOS ONE 8 (5): e65295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065295.</ref> When the results from the modeling were not scaled according to size, then both spinosaurids performed better than all the crocodilians in resistance to bending and torsion, due to their larger size.<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013 /> Thus, Cuff and Rayfield suggest that the skulls are not efficiently built to deal well with relatively large, struggling prey, but that the spinosaurids may overcome prey simply by their size advantage, and not skull build<ref name=CuffandRayfield2013 /> Sues and colleagues studied the construction of the spinosaurid skull, and concluded that their mode of feeding was to use extremely quick, powerful strikes to seize small prey items using their jaws, whilst employing the powerful neck muscles in rapid up-and-down motion. Due to the narrow snout, vigorous side-to-side motion of the skull during prey capture is unlikely.<ref name="suesetal2002" /> Based the size and positions of their nostrils, Sales & Schultz (2017) suggested that ''Spinosaurus'' possessed a greater reliance on its sense of smell and a more piscivorous lifestyle than ''Irritator'' and baryonychines.<ref name="salesschultz">{{cite journal|first1=M.A.F. |last1=Sales |first2=C.L. |last2=Schultz |year=2017 |title=Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=12 |issue=11 |pages=e0187070 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0187070 |url=http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0187070}}</ref> |

||

=== Dorsal sails === |

|||

| ⚫ | This has been compared to the dorsal fin of a [[sailfish]].<ref name=":0">{{cite journal|title=Gimsa, J., Sleigh, R., Gimsa, U., (2015) : "The riddle of ''Spinosaurus aegyptiacus'' ' dorsal sail". University of Rostock, Chair for Biophysics, Gertrudenstr. 11A, 18057 Rostock, Germany}}</ref> These structures have had many proposed functions over the years, such as [[thermoregulation]],<ref name="LBH75">{{cite book|title=The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs|last=Halstead|first=L.B.|publisher=Eurobook Limited|year=1975|isbn=0-85654-018-8|location=London|pages=1–116|authorlink=Beverly Halstead}}</ref> to aid in swimming,<ref name=":0" /> to store energy or insulate the animal, or for display purposes, such as intimidating rivals and predators, or attracting mates.<ref name="JBB972">{{cite journal|last=Bailey|first=J.B.|year=1997|title=Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=71|issue=6|pages=1124–1146|jstor=1306608}}</ref><ref name="Stromer15" /> |

||

== Paleoecology == |

== Paleoecology == |

||

[[File:Spinosaurus_durbed.jpg|thumb|right|''Spinosaurus'' spent much of its time in or around water.]] |

|||

===Habitat |

=== Habitat === |

||

For example: ''Spinosaurus,'' from the Cenomanian of North Africa, lived in a humid, tropical environment of [[tidal flats]] and channels with [[mangrove]] forests.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Smith|first=J. B.|date=2001-06-01|title=A Giant Sauropod Dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous Mangrove Deposit in Egypt|url=http://sci-hub.tw/10.1126/science.1060561|journal=Science|volume=292|issue=5522|pages=1704–1706|doi=10.1126/science.1060561|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> Similarly to the Brazilian spinosaurine ''Oxalaia'', which also lived in the tropics, in large forests of [[conifers]], [[Fern|ferns]], and [[horsetails]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|date=2014-08-01|title=The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895981114000364|journal=Journal of South American Earth Sciences|language=en|volume=53|pages=50–58|doi=10.1016/j.jsames.2014.04.002|issn=0895-9811}}</ref> ''Oxalaia,'' from the Cenomanian [[Alcântara Formation]] and, ''Irritator,'' from the Aptian-Albian [[Santana Formation]] lived in arid to semi-arid regions, experiencing short, intense rainfall followed by long dry periods.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Naish|first=Darren|last2=Martill|first2=David M.|last3=Frey|first3=Eberhard|date=17 May 2006|title=Ecology, Systematics and Biogeographical Relationships of Dinosaurs, Including a New Theropod, from the Santana Formation (?Albian, Early Cretaceous) of Brazil|url=http://sci-hub.tw/10.1080/08912960410001674200|journal=Historical Biology|volume=16|issue=2-4|pages=57–70|doi=10.1080/08912960410001674200|issn=0891-2963|via=}}</ref><ref name=":2" /> Much of the vegetation from ''Irritator''<nowiki/>'s habitat could survive long periods without water.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

From this it is apparent that Cenomanian Northern Africa and northeastern Brazil, inhabited by ''Spinosaurus'' and ''Oxalaia'' respectively, shared an extremely similar climate and many of the same biota. This is a probable result of [[Gondwana]], a prehistoric [[supercontinent]] comprising most of the modern southern hemisphere, as South America and Africa drifted apart from each other during the [[Middle Jurassic]], the flora and fauna on either continent would have continued to evolve separately from each other, contributing to small anatomical differences between taxa.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|date=2015-08-01|title=Middle Cretaceous dinosaur assemblages from northern Brazil and northern Africa and their implications for northern Gondwanan composition|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895981114001424|journal=Journal of South American Earth Sciences|language=en|volume=61|pages=147–153|doi=10.1016/j.jsames.2014.10.005|issn=0895-9811}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{Cite journal|last=William Elliott HONE|first=David|last2=Richard HOLTZ|first2=Thomas|date=2017-06-01|title=A Century of Spinosaurs - A Review and Revision of the Spinosauridae with Comments on Their Ecology|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318228524_A_Century_of_Spinosaurs_-_A_Review_and_Revision_of_the_Spinosauridae_with_Comments_on_Their_Ecology|journal=Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition|volume=91|pages=1120–1132|doi=10.1111/1755-6724.13328}}</ref> [[File:Spinosaurus_durbed.jpg|thumb|right|''Spinosaurus'' spent much of its time in or around water.]] |

|||

====Bone histology==== |

|||

A 2010 publication by Romain Amiot and colleagues found that [[isotopes of oxygen|oxygen isotope]] ratios of spinosaurid bones indicates semiaquatic lifestyles. Isotope ratios from teeth from ''Baryonyx'', ''Irritator'', ''Siamosaurus'', and ''Spinosaurus'' were compared with isotopic compositions from contemporaneous theropods, turtles, and crocodilians. The study found that, among theropods, spinosaurid isotope ratios were closer to those of turtles and crocodilians. ''Siamosaurus'' specimens tended to have the largest difference from the ratios of other theropods, and ''Spinosaurus'' tended to have the least difference. The authors concluded that spinosaurids, like modern crocodilians and hippopotamuses, spent much of their daily lives in water. The authors also suggested that semiaquatic habits and piscivory in spinosaurids can explain how spinosaurids coexisted with other large theropods: by feeding on different prey items and living in different habitats, the different types of theropods would have been out of direct competition.<ref name="RMetal10" /> |

A 2010 publication by Romain Amiot and colleagues found that [[isotopes of oxygen|oxygen isotope]] ratios of spinosaurid bones indicates semiaquatic lifestyles. Isotope ratios from teeth from ''Baryonyx'', ''Irritator'', ''Siamosaurus'', and ''Spinosaurus'' were compared with isotopic compositions from contemporaneous theropods, turtles, and crocodilians. The study found that, among theropods, spinosaurid isotope ratios were closer to those of turtles and crocodilians. ''Siamosaurus'' specimens tended to have the largest difference from the ratios of other theropods, and ''Spinosaurus'' tended to have the least difference. The authors concluded that spinosaurids, like modern crocodilians and hippopotamuses, spent much of their daily lives in water. The authors also suggested that semiaquatic habits and piscivory in spinosaurids can explain how spinosaurids coexisted with other large theropods: by feeding on different prey items and living in different habitats, the different types of theropods would have been out of direct competition.<ref name="RMetal10" /> |

||

In 2018, an osteological analysis on a fragmentary [[tibia]], (designated LPP-PV-0042) revealed [[osteosclerosis]] (high bone density) was present in the specimen, this condition had previously only been seen in ''Spinosaurus,'' |

|||

===Feeding=== |

===Feeding=== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:2013-03_Naturkundemuseum_Berlin_Dickschupperfisch_Lepidotes_maximus_anagoria.JPG|thumb|right|A fossil of the fish ''[[Scheenstia]]'', prey of ''Baryonyx'']] |

||

Direct fossil evidence shows that spinosaurids fed on fish as well as a variety of other small to medium-sized animals, including small dinosaurs. ''Baryonyx'' was found with scales of the prehistoric fish, ''[[ |

Direct fossil evidence shows that spinosaurids fed on fish as well as a variety of other small to medium-sized animals, including small dinosaurs. ''Baryonyx'' was found with scales of the prehistoric fish, ''[[Scheenstia]]'', in its body cavity, and these were abraded, hypothetically by gastric juices.<ref name="Buffetautetal.2004" /><ref name=Rayfield2011 /> Bones of a young Iguanodon, also abraded, were found alongside this specimen.<ref name="suesetal2002" /> If these represent ''Baryonyx''’s meal, ''Baryonyx'' was, whether in this case a hunter, or a scavenger, an eater of more diverse fare than fish.<ref name=Buffetautetal.2004 /> Moreover, there is a documented example of a spinosaurid having eaten a [[pterosaur]], as spinosaurid teeth were found embedded within the fossil vertebrae of one found in the Santana Formation of Brazil.<ref name=Buffetautetal.2004 /> This may represent a predation event, but Buffetaut ''et al.'' consider it more likely that the spinosaurid scavenged the pterosaur carcass after its death. |

||

==Timeline of genera== |

==Timeline of genera== |

||

Revision as of 23:32, 7 May 2018

| This user page is actively undergoing a major edit for a short while. A lot of new sections, information, and references will be added as well as multiple minor changes in order to prepare the article for a more in-depth GA review. Visit the GAN talk page for more information. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. This page was last edited at 23:32, 7 May 2018 (UTC) (6 years ago) – this estimate is cached, . Please remove this template if this page hasn't been edited for a significant time. If you are the editor who added this template, please be sure to remove it or replace it with {{Under construction}} between editing sessions. |

| Spinosaurids | |

|---|---|

| |

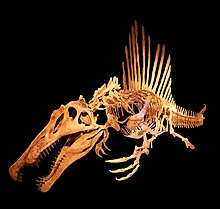

| Skeletal reconstruction of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | PaleoGeekSquared/sandbox |

| Type species | |

| Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915

| |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

Spinosauridae (meaning 'spined lizards') is a family of megalosauroidean theropod dinosaurs, it contains the eponymous Spinosaurus, which is currently one of if not the largest terrestrial predator known from the fossil record, and might have measured up to 15 m (49 ft) in length.[1] Most spinosaurids lived during the Cretaceous period, and fossils of them have been recovered worldwide, including Africa, Europe, South America, Asia and Australia.

They were large bipedal carnivores with elongated, crocodile-like skulls, sporting conical teeth with no or only very tiny serrations, and oftentimes small crests on top of their heads. The teeth in the front end of the lower jaw fanned out into a structure called a rosette, which gave the animal a characteristic look. Their shoulder blades were robust and hook-shaped, bearing relatively large forelimbs with enlarged claws on the first digit of their hands. Some genera also had unusually elongated neural spines, which might have supported sails or humps made of skin and fat tissue.

Sediment analysis has revealed that most spinosaurids inhabited fresh-to-brackish shallow water habitats in tropical regions, often near lagoons, marshes, and mudflats. These environments would have been optimal for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, which has also been corroborated by isotope and osteological (bone) analyses done on several taxa in this clade. Coupled with their conical teeth, designed for gripping prey instead of ripping flesh, this would have made them specialists, hunting mostly fish, while feeding opportunistically on other animals.

Description

Anatomical characteristics

Spinosaurids have relatively large forearms and an enlarged claw on the first digit of the hand.[2] They have a hook shaped coracoid, external nares which are at least behind the teeth of the premaxillae or even further posterior on the skull, a long secondary palate, a terminal rosette of enlarged teeth at the front of both the upper and lower jaws, and subconical teeth with small denticles or no denticles.[2][3]

Dorsal sails

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, the type species for the family and subfamily, is known for the vertebrae with elongated neural spines, some over a meter tall, which have been reconstructed as a sail or hump running down its back.[4]

In Ichthyovenator, this sail is a half a meter at its highest and split into two at the sacral vertebrae.[5] Suchomimus also has a low, ridge-like sail over its hips, smaller than that of Spinosaurus.[4] Baryonyx, however, lacks a sail.[6] Because of phylogenetic bracketing, other spinosaurids such as Irritator might have also had extended neural spines, but sufficient fossil vertebra are needed to know for certain.

Bony crests

Another feature that makes spinosaurid skulls unique from most other theropods, is that they often feature relatively large sagittal crests formed from their nasal bones. These crests have been present in Spinosaurus as a ridge-shaped structure, and in Suchomimus and Baryonyx as smaller bumps on top of the skull.[7] They have also been seen (to a smaller degree) in ,[8] and Cristatusaurus.[9]

Evolutionary history

Timespan

The spinosaurids are known to exist from as early as the Late Jurassic, through characteristic teeth which were found in Tendaguru, Tanzania, and attributed to Ostafrikasaurus,[10] 15 Million years prior to Siamosaurus. Baryonychines were common, as represented by Baryonyx, which lived during the Barremian of England and Spain. Baryonyx-like teeth are found from the earlier Hauterivian and later Aptian sediments of Spain, as well as the Hauterivian of England, and the Aptian of Niger. The earliest record of spinosaurines is from Africa; they are present in Albian sediments of Tunisia and Algeria, and in Cenomanian sediments of Egypt and Morocco. Spinosaurines are also found in Hauterivian and Aptian-Albian sediments of Thailand, and Southern China. In Africa, baronychines were common in the Aptian, and then replaced by spinosaurines in the Albian and Cenomanian.[11]

Some intermediate specimens extend the known range of spinosaurids past the youngest dates of named taxa. A single baryonychine tooth was found from the mid-Santonian, in the Majiacun Formation of Henan, China.[12] Possible spinosaur remains were also reported from the late Maastrichtian Maevarano Formation.[13]

Localities

Confirmed spinosaurids have been found on every continent except for North America and Antarctica. The first of which was discovered in 1912 at the Bahariya Formation in Egypt and described in 1915 as Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.[14] Over the years Africa has shown a great abundance in spinosaurid discoveries,[15] such as in the Kem Kem beds of Morocco, which housed an ecosystem full of many large coexisting predators.[16][17] A fragment of a spinosaurine lower jaw from the Early Cretaceous was also reported from Tunisia, and referred to Spinosaurus.[11]

Spinosaurinae's range has also extended to South America, particularly Brazil, with the discoveries of Irritator, Angaturama, and Oxalaia.[19][20] There was also a fossil tooth in Argentina which has been referred to spinosauridae by Salgado et al.[21] This referral is doubted by Tanaka, who offers Hamadasuchus, a crocodilian, as the most likely animal of origin for these teeth.[22]

Baryonychines have been found in Africa, with Suchomimus and Cristatusaurus,[11][23][9] as well as in Europe, with Baryonyx and Suchosaurus.[24] Baryonyx-like teeth are also reported from the Ashdown Sands of Sussex, in England, and the Burgos Province, in Spain. A partial skeleton and many fossil teeth also hint at the possibility of spinosaurids being widespread in Asia. As of 2012, three have been named: Ichthyovenator; a baryonychine,[5] and Siamosaurus and "Sinopliosaurus" fusuiensis; two indeterminate spinosaurids.[11][12] At la Cantalera-1, a site in the Early Barremanian Blesa Formation in Treul, Spain, two types of spinosaurid teeth were found, and they were assigned, tentatively, as indeterminate spinosaurine and baryonychine taxa.[25]

An intermediate spinosaurid was discovered in the Early Cretaceous Eumeralla Formation, Australia.[26] It is known from a single 4 cm long partial cervical vertebra, designated P221081. It is missing most of the neural arch. The specimen is from a juvenile estimated to be about 2 to 3 meters long (6-9 ft). Out of all spinosaurs it most closely resembles Baryonyx.[27]

Classification

The family Spinosauridae was named by Ernst Stromer in 1915 to include the single genus Spinosaurus. The clade was expanded as more close relatives of Spinosaurus were uncovered. The first cladistic definition of spinosauridae was provided by Paul Sereno in 1998 (as "All spinosaurids closer to Spinosaurus than to Torvosaurus).

Taxonomy

Traditionally, spinosauridae is divided into two subfamilies: spinosaurinae, which contains the genera Irritator, Oxalaia, and Spinosaurus,[11] is marked by unserrated, straight teeth, and external nares which are further back on the skull than in baryonychinae.[2][3] And baryonychinae, which contains the genera Baryonyx and Suchomimus,[11] is marked by serrated, slightly curved teeth, smaller size, and more teeth in the lower jaw behind the terminal rosette than in spinosaurines.[2][3] Others such as Siamosaurus, may belong to either Suchomimus or Spinosaurus, but are too incompletely known to be assigned with confidence.[11]

Phylogeny

The subfamily Spinosaurinae was named by Sereno in 1998, and defined by Holtz et al. (2004) as all taxa closer to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus than to Baryonyx walkeri. And the subfamily Baryonychinae was named by Charig & Milner in 1986. They erected both the subfamily and the family Baryonychinae for the newly discovered Baryonyx, before it was referred to the Spinosauridae. Their subfamily was defined by Holtz et al. in 2004, as the complementary clade of all taxa closer to Baryonyx walkeri than to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Examinations by Marcos Sales and Cesar Schultz et al. indicate that the South American spinosaurids Angaturama, Irritator, and Oxalaia were intermediate between Baronychinae and Spinosaurinae based on their craniodental features and cladistic analysis. This indicates that Baryonychinae may in fact be non-monophyletic. Their cladogram can be seen below.[28]

The next cladogram displays an analysis of Tetanurae simplified to show only Spinosauridae from Allain et al. (2012):[29]

| Spinosauridae | |

Paleobiology

Lifestyle and hunting

Spinosaurid teeth resemble those of crocodiles, which are used for piercing and holding prey. Therefore, teeth with small or no serrations, such as in spinosaurids, were not good for cutting or ripping into flesh but instead to ensure a strong grip on a struggling prey animal.[30] Spinosaur jaws were likened by Vullo et al. to those of the pike conger eel, in what they hypothesized was convergent evolution for aquatic feeding.[31] Both kinds of animals have some teeth in the end of the upper and lower jaws that are larger than the others and an area of the upper jaw with smaller teeth, creating a gap into which the enlarged teeth of the lower jaw fit, with the full structure called a terminal rosette.[31]

Spinosaurids have in the past often been considered mainly fish-eaters (piscivores), based on comparisons of their jaws with those of modern crocodilians.[3] Rayfield and colleagues, in 2007, conducted biomechanical studies on the skull of the European spinosaurid Baryonyx, which has a long, laterally compressed skull, comparing it to gharial (long, narrow, tubular) and alligator (flat and wide) skulls.[32] They found that the structure of baryonychine jaws converged on that of gharials, in that the two taxa showed similar response patterns to stress from simulated feeding loads, and did so with and without the presence of a (simulated) secondary palate. The gharial, exemplar of a long, narrow, and tubular snout, is a fish specialist. However, this snout anatomy doesn’t preclude other options for the spinosaurids. While the gharial is the most extreme example and a fish specialist, and Australian freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni), which have similarly shaped skulls to gharials, also specialize more on fish than sympatric, broad snouted crocodiles. And are opportunistic feeders which eat all manner of small aquatic prey, including insects and crustaceans.[32] Thus, their aptly shaped snouts correlate with fish-eating, this is consistent with hypotheses of this diet for spinosaurids, in particular baryonychines, but it does not indicate that they were solely piscivorous.

A further study by Cuff and Rayfield (2013) on the skulls of Spinosaurus and Baryonyx did not recover similarities in the skulls of Baryonyx and the gharial that the previous study did. Baryonyx had, in models where the size difference of the skulls was corrected for, greater resistance to torsion and dorsoventral bending than both Spinosaurus and the gharial, while both spinosaurids were inferior to the gharial, alligator, and slender-snouted crocodile in resisting torsion and medio-lateral bending.[33] When the results from the modeling were not scaled according to size, then both spinosaurids performed better than all the crocodilians in resistance to bending and torsion, due to their larger size.[33] Thus, Cuff and Rayfield suggest that the skulls are not efficiently built to deal well with relatively large, struggling prey, but that the spinosaurids may overcome prey simply by their size advantage, and not skull build[33] Sues and colleagues studied the construction of the spinosaurid skull, and concluded that their mode of feeding was to use extremely quick, powerful strikes to seize small prey items using their jaws, whilst employing the powerful neck muscles in rapid up-and-down motion. Due to the narrow snout, vigorous side-to-side motion of the skull during prey capture is unlikely.[30] Based the size and positions of their nostrils, Sales & Schultz (2017) suggested that Spinosaurus possessed a greater reliance on its sense of smell and a more piscivorous lifestyle than Irritator and baryonychines.[28]

Dorsal sails

This has been compared to the dorsal fin of a sailfish.[34] These structures have had many proposed functions over the years, such as thermoregulation,[35] to aid in swimming,[34] to store energy or insulate the animal, or for display purposes, such as intimidating rivals and predators, or attracting mates.[36][14]

Paleoecology

Habitat

For example: Spinosaurus, from the Cenomanian of North Africa, lived in a humid, tropical environment of tidal flats and channels with mangrove forests.[37] Similarly to the Brazilian spinosaurine Oxalaia, which also lived in the tropics, in large forests of conifers, ferns, and horsetails.[38] Oxalaia, from the Cenomanian Alcântara Formation and, Irritator, from the Aptian-Albian Santana Formation lived in arid to semi-arid regions, experiencing short, intense rainfall followed by long dry periods.[39][38] Much of the vegetation from Irritator's habitat could survive long periods without water.[39]

From this it is apparent that Cenomanian Northern Africa and northeastern Brazil, inhabited by Spinosaurus and Oxalaia respectively, shared an extremely similar climate and many of the same biota. This is a probable result of Gondwana, a prehistoric supercontinent comprising most of the modern southern hemisphere, as South America and Africa drifted apart from each other during the Middle Jurassic, the flora and fauna on either continent would have continued to evolve separately from each other, contributing to small anatomical differences between taxa.[38][40]

Bone histology

A 2010 publication by Romain Amiot and colleagues found that oxygen isotope ratios of spinosaurid bones indicates semiaquatic lifestyles. Isotope ratios from teeth from Baryonyx, Irritator, Siamosaurus, and Spinosaurus were compared with isotopic compositions from contemporaneous theropods, turtles, and crocodilians. The study found that, among theropods, spinosaurid isotope ratios were closer to those of turtles and crocodilians. Siamosaurus specimens tended to have the largest difference from the ratios of other theropods, and Spinosaurus tended to have the least difference. The authors concluded that spinosaurids, like modern crocodilians and hippopotamuses, spent much of their daily lives in water. The authors also suggested that semiaquatic habits and piscivory in spinosaurids can explain how spinosaurids coexisted with other large theropods: by feeding on different prey items and living in different habitats, the different types of theropods would have been out of direct competition.[17]

In 2018, an osteological analysis on a fragmentary tibia, (designated LPP-PV-0042) revealed osteosclerosis (high bone density) was present in the specimen, this condition had previously only been seen in Spinosaurus,

Feeding

Direct fossil evidence shows that spinosaurids fed on fish as well as a variety of other small to medium-sized animals, including small dinosaurs. Baryonyx was found with scales of the prehistoric fish, Scheenstia, in its body cavity, and these were abraded, hypothetically by gastric juices.[19][3] Bones of a young Iguanodon, also abraded, were found alongside this specimen.[30] If these represent Baryonyx’s meal, Baryonyx was, whether in this case a hunter, or a scavenger, an eater of more diverse fare than fish.[19] Moreover, there is a documented example of a spinosaurid having eaten a pterosaur, as spinosaurid teeth were found embedded within the fossil vertebrae of one found in the Santana Formation of Brazil.[19] This may represent a predation event, but Buffetaut et al. consider it more likely that the spinosaurid scavenged the pterosaur carcass after its death.

Timeline of genera

References

- ^ Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. Supplementary Information

- ^ a b c d Sereno, Paul C., Allison L. Beck, Didier B. Dutheil, Boubacar Gado, Hans C. E. Larsson, Gabrielle H. Lyon, Jonathan D. Marcot, et al. 1998. “A Long-Snouted Predatory Dinosaur from Africa and the Evolution of Spinosaurids.” Science 282 (5392): 1298–1302. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298.

- ^ a b c d e Rayfield, Emily J. 2011. “Structural Performance of Tetanuran Theropod Skulls, with Emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae.” Special Papers in Palaeontology 86 (November). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250916680_Structural_performance_of_tetanuran_theropod_skulls_with_emphasis_on_the_Megalosauridae_Spinosauridae_and_Carcharodontosauridae.

- ^ a b Hecht, Jeff. 1998. “Fish Swam in Fear.” New Scientist. November 21. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg16021610-300-fish-swam-in-fear/.

- ^ a b Allain, R.; Xaisanavong, T.; Richir, P.; Khentavong, B. (2012). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–377. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..369A. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7. PMID 22528021.

- ^ Charig, A. J.; Milner, A. C. (1997). "Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London. 53: 11–70.

- ^ Charig, A. J.; Milner, A. C. (1997). "Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London. 53: 11–70.

- ^ Sues, H. D.; Frey, E.; Martill, D. M.; Scott, D. M. (2002). "Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 535–547. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Taquet, P. and Russell, D.A. (1998). "New data on spinosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of the Sahara". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes 327: 347-353

- ^ Buffetaut, Eric. 2008. “Spinosaurid Teeth from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania, with Remarks on the Evolutionary and Biogeographical History of the Spinosauridae.” https://www.academia.edu/3101178/Spinosaurid_teeth_from_the_Late_Jurassic_of_Tendaguru_Tanzania_with_remarks_on_the_evolutionary_and_biogeographical_history_of_the_Spinosauridae

- ^ a b c d e f g Buffetaut, Eric, and Mohamed Ouaja. 2002. “A New Specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with Remarks on the Evolutionary History of the Spinosauridae.” Bulletin de La Société Géologique de France 173 (5): 415–21. doi:10.2113/173.5.415.

- ^ a b Hone, Dave, Xing Xu, Deyou Wang, and Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 2010. “A Probable Baryonychine (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) Tooth from the Upper Cretaceous of Henan Province, China (PDF Download Available).” ResearchGate. January. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271967379_A_probable_Baryonychine_Theropoda_Spinosauridae_tooth_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_of_Henan_Province_China.

- ^ Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loueff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth M. P.; Noto, Christopher N. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 624. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b Stromer, E. (1915). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 3. Das Original des Theropoden Spinosaurus aegyptiacus nov. gen., nov. spec". Abhandlungen der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-physikalische Klasse (in German). 28 (3): 1–32.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Benyoucef, Madani, Emilie Läng, Lionel Cavin, Kaddour Mebarki, Mohammed Adaci, and Mustapha Bensalah. 2015. “Overabundance of Piscivorous Dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) in the Mid-Cretaceous of North Africa: The Algerian Dilemma.” Cretaceous Research 55 (July): 44–55. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.02.002.

- ^ Hendrickx, Christophe, Octávio Mateus, and Eric Buffetaut. 2016. “Morphofunctional Analysis of the Quadrate of Spinosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the Presence of Spinosaurus and a Second Spinosaurine Taxon in the Cenomanian of North Africa.” PLOS ONE 11 (1): e0144695. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144695.

- ^ a b Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..139A. doi:10.1130/G30402.1.

- ^ Farke, Andrew A.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Rich, Thomas H.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Hall, Mike (2012). "Theropod Fauna from Southern Australia Indicates High Polar Diversity and Climate-Driven Dinosaur Provinciality". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e37122. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037122. ISSN 1932-6203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Buffetaut, Eric, David Martill, and François Escuillié. 2004. “Pterosaurs as Part of a Spinosaur Diet.” Nature 430. doi:10.1038/430033a.

- ^ Kellner, Alexander W.A.; Sergio A.K. Azevedeo; Elaine B. Machado; Luciana B. Carvalho; Deise D.R. Henriques (2011). "A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100006. ISSN 0001-3765.

- ^ Salgado, Leonardo, José I. Canudo, Alberto C. Garrido, José I. Ruiz-Omeñaca, Rodolfo A. García, Marcelo S. de la Fuente, José L. Barco, and Raúl Bollati. 2009. “Upper Cretaceous Vertebrates from El Anfiteatro Area, Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina.” Cretaceous Research 30 (3): 767–84. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.01.001.

- ^ Tanaka, Gengo. 2017. “Fine Sculptures on a Tooth of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco.” Bulletin of Gunma …. Accessed May 30. https://www.academia.edu/1300482/Fine_sculptures_on_a_tooth_of_Spinosaurus_Dinosauria_Theropoda_from_Morocco.

- ^ Sereno, P.C.; Beck, A.L.; Dutheil, D.B.; Gado, B.; Larsson, H.C.E.; Lyon, G.H.; Marcot, J.D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Sadleir, R.W.; Sidor, C.A.; Varricchio, D.D.; Wilson, G.P; Wilson, J.A. (1998). "A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids". Science. 282 (5392): 1298–1302. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.1298S. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298. PMID 9812890. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ Mateus, O.; Araújo, R.; Natário, C.; Castanhinha, R. (2011). "A new specimen of the theropod dinosaur Baryonyx from the early Cretaceous of Portugal and taxonomic validity of Suchosaurus" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2827: 54–68.

- ^ Alonso, Antonio, and José Ignacio Canudo. 2016. “On the Spinosaurid Theropod Teeth from the Early Barremian (Early Cretaceous) Blesa Formation (Spain).” Historical Biology 28 (6): 823–34. doi:10.1080/08912963.2015.1036751.

- ^ "Australian 'Spinosaur' unearthed". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ Barrett, P. M.; Benson, R. B. J.; Rich, T. H.; Vickers-Rich, P. (2011). "First spinosaurid dinosaur from Australia and the cosmopolitanism of Cretaceous dinosaur faunas". Biology Letters. 7 (6): 933–936. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0466. ISSN 1744-9561.

- ^ a b Sales, M.A.F.; Schultz, C.L. (2017). "Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil". PLoS ONE. 12 (11): e0187070. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Allain, R.; Xaisanavong, T.; Richir, P.; Khentavong, B. (2012). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–377. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..369A. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7. PMID 22528021.

- ^ a b c Sues, Hans-Dieter, Eberhard Frey, David M. Martill, and Diane M. Scott. 2002. “Irritator Challengeri, a Spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 535–47. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Vullo, R.; Allain, R.; Cavin, L. (2016). "Convergent evolution of jaws between spinosaurid dinosaurs and pike conger eels". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00284.2016.

- ^ a b Rayfield, Emily J., Angela C. Milner, Viet Bui Xuan, and Philippe G. Young. 2007. “Functional Morphology of Spinosaur ‘crocodile-Mimic’ Dinosaurs.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 892–901. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[892:FMOSCD]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c Cuff, Andrew R., and Emily J. Rayfield. 2013. “Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians.” PLOS ONE 8 (5): e65295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065295.

- ^ a b "Gimsa, J., Sleigh, R., Gimsa, U., (2015) : "The riddle of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus ' dorsal sail". University of Rostock, Chair for Biophysics, Gertrudenstr. 11A, 18057 Rostock, Germany".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Halstead, L.B. (1975). The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs. London: Eurobook Limited. pp. 1–116. ISBN 0-85654-018-8.

- ^ Bailey, J.B. (1997). "Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?". Journal of Paleontology. 71 (6): 1124–1146. JSTOR 1306608.

- ^ Smith, J. B. (2001-06-01). "A Giant Sauropod Dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous Mangrove Deposit in Egypt". Science. 292 (5522): 1704–1706. doi:10.1126/science.1060561. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ a b c "The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 53: 50–58. 2014-08-01. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2014.04.002. ISSN 0895-9811.

- ^ a b Naish, Darren; Martill, David M.; Frey, Eberhard (17 May 2006). "Ecology, Systematics and Biogeographical Relationships of Dinosaurs, Including a New Theropod, from the Santana Formation (?Albian, Early Cretaceous) of Brazil". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 57–70. doi:10.1080/08912960410001674200. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ "Middle Cretaceous dinosaur assemblages from northern Brazil and northern Africa and their implications for northern Gondwanan composition". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 61: 147–153. 2015-08-01. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2014.10.005. ISSN 0895-9811.

- ^ William Elliott HONE, David; Richard HOLTZ, Thomas (2017-06-01). "A Century of Spinosaurs - A Review and Revision of the Spinosauridae with Comments on Their Ecology". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 91: 1120–1132. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.13328.

External links

- Spinosauridae

- Spinosauridae on the Theropod Database

- Spinosaurids

- Kimmeridgian first appearances

- Kimmeridgian taxonomic families

- Tithonian taxonomic families

- Berriasian taxonomic families

- Valanginian taxonomic families

- Hauterivian taxonomic families

- Barremian taxonomic families

- Aptian taxonomic families

- Albian taxonomic families

- Cenomanian taxonomic families

- Cenomanian extinctions

- Fossil taxa described in 1915

- Taxa named by Ernst Stromer