Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham: Difference between revisions

RetiredDuke (talk | contribs) m typo |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m Alter: pages, template type, doi, doi-broken-date. Add: doi-broken-date, doi. Removed parameters. | You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | User-activated. |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

* {{cite book|title=Henry V|last=Allmand|first=C. T.|date=2014|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-30021-293-8|location=New Haven, CT|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=Henry V|last=Allmand|first=C. T.|date=2014|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-30021-293-8|location=New Haven, CT|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Armstrong |first1=C. A. J. |title=Politics and the Battle of St. Albans, 1455 |journal=Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research |date=1960 |volume=33 |pages=1–72 |ref=harv |oclc=1001092266}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Armstrong |first1=C. A. J. |title=Politics and the Battle of St. Albans, 1455 |journal=Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research |date=1960 |volume=33 |pages=1–72 |ref=harv |oclc=1001092266}} |

||

* {{cite journal|last= Baugh|first= A. C. |

* {{cite journal|last= Baugh|first= A. C.|year=1933|title=Documenting Sir Thomas Malory|journal= Speculum|volume=8|pages= 3–29|oclc=504113521|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=From Lord to Patron: Lordship in Late Medieval England|last=Bean|first=J. M. W.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1989|isbn=978-0-71902-855-7|location=Manchester|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=From Lord to Patron: Lordship in Late Medieval England|last=Bean|first=J. M. W.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1989|isbn=978-0-71902-855-7|location=Manchester|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=Memorials of the Order of the Garter, from Its Foundation to the Present Time<!-- full title: Memorials of the Order of the Garter, from Its Foundation to the Present Time: Including the History of the Order; Biographical Notices of the Knights in the Reigns of Edward III, and Richard II, the Chronological Succession of the Members, and Many Curious Particulars Relating to English and French History from Hitherto Unpublished Documents-->|last=Beltz|first=G. F.|publisher=W. Pickering|year=1841|oclc=4706731|location=London|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=Memorials of the Order of the Garter, from Its Foundation to the Present Time<!-- full title: Memorials of the Order of the Garter, from Its Foundation to the Present Time: Including the History of the Order; Biographical Notices of the Knights in the Reigns of Edward III, and Richard II, the Chronological Succession of the Members, and Many Curious Particulars Relating to English and French History from Hitherto Unpublished Documents-->|last=Beltz|first=G. F.|publisher=W. Pickering|year=1841|oclc=4706731|location=London|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Tudor Nobility|last=Bernard|first=G. W.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-71903-625-5|location=Manchester|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Tudor Nobility|last=Bernard|first=G. W.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-71903-625-5|location=Manchester|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Fee Tail and the Common Recovery in Medieval England: 1176–1502|last=Biancalana|first=J.|date=2001|publisher=Cambridge University Press |

* {{cite book|title=The Fee Tail and the Common Recovery in Medieval England: 1176–1502|last=Biancalana|first=J.|date=2001|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-13943-082-1|location=Cambridge |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Wars of the Roses|last=Britnell|first=R. H.|publisher=St. Martin's Press|year=1995|isbn=978-0-31212-699-5|editor-last=Pollard|editor-first=A. J.|location=London|pages=41–64|chapter=The Economic Context|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Wars of the Roses|last=Britnell|first=R. H.|publisher=St. Martin's Press|year=1995|isbn=978-0-31212-699-5|editor-last=Pollard|editor-first=A. J.|location=London|pages=41–64|chapter=The Economic Context|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, c.1437–1509|last=Carpenter|first=C.|date=1997|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-52131-874-7|location=Cambridge|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, c.1437–1509|last=Carpenter|first=C.|date=1997|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-52131-874-7|location=Cambridge|ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

* {{cite book|title=The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant|last=Cokayne|first= G. E.|publisher=St Catherine Press|year=1913|volume=3|location=London|oclc=312790481|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant|last=Cokayne|first= G. E.|publisher=St Catherine Press|year=1913|volume=3|location=London|oclc=312790481|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant|last=Cokayne|first= G. E.|publisher=St Catherine Press|year=1959|volume=12|location=London|oclc=312826326|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant|last=Cokayne|first= G. E.|publisher=St Catherine Press|year=1959|volume=12|location=London|oclc=312826326|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal|last2=Carpenter|first2= D. A. |

* {{cite journal|last2=Carpenter|first2= D. A.|year=1991|title= Bastard feudalism Revised|journal=Past & Present|volume=131|pages=165–189|oclc=664602455|ref=harv|last1=Crouch|first1= D.}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Hundred Years War|date=2003|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-0-23062-969-1|last=Curry|first=A.|location=London|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Hundred Years War|date=2003|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-0-23062-969-1|last=Curry|first=A.|location=London|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite |

* {{cite journal |last1=Davies |first1=C. |title=Stafford, Henry, Second Duke of Buckingham (1455–1483), Magnate and Rebel |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26204 |website=OxfordDictionary of National Biography |accessdate=11 January 2019 |ref=harv |archiveurl=https://archive.is/fVOjj |archivedate=11 January 2019 |date=2004|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001 |doi-broken-date=2019-01-15 }} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare|last2=Wells|first2=S.|last3=Sullivan|first3=E.|date=2015|publisher=Oxford University Press |

* {{cite book|title=The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare|last2=Wells|first2=S.|last3=Sullivan|first3=E.|date=2015|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19870-873-5|location=Oxford|ref=harv|last1=Dobson|first1=M.}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Dunham|first=I. W.|title=Dunham Genealogy: English and American Branches of the Dunham Family|year=1907|publisher=Bulletin Print|location=Norwich, CT|oclc=10378604|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Dunham|first=I. W.|title=Dunham Genealogy: English and American Branches of the Dunham Family|year=1907|publisher=Bulletin Print|location=Norwich, CT|oclc=10378604|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces|last2=Stevenson|first2=J.|publisher=Boydell Press|year=2012|isbn=978-1-84383-697-1|location=Woodbridge|ref=harv|last1=Gertsman|first1=E.}} |

* {{cite book|title=Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces|last2=Stevenson|first2=J.|publisher=Boydell Press|year=2012|isbn=978-1-84383-697-1|location=Woodbridge|ref=harv|last1=Gertsman|first1=E.}} |

||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

* {{cite book|last=Harris|first=P.|title=Income Tax in Common Law Jurisdictions: From the Origins to 1820|volume=I|year=2006|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge |isbn= 978-0-51149-548-9|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Harris|first=P.|title=Income Tax in Common Law Jurisdictions: From the Origins to 1820|volume=I|year=2006|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge |isbn= 978-0-51149-548-9|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=Cardinal Beaufort: A Study of Lancastrian Ascendancy and Decline|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|publisher=Clarendon Press|year=1988|isbn=978-0-19820-135-9|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=Cardinal Beaufort: A Study of Lancastrian Ascendancy and Decline|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|publisher=Clarendon Press|year=1988|isbn=978-0-19820-135-9|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{Cite |

* {{Cite journal|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1859|title=Beaufort, Henry (1375?–1447)|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|date=2004a|website=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|archive-url=https://archive.vn/IHfF9|archive-date=5 January 2019|ref=harv|dead-url=no|access-date=5 January 2019|subscription=Yes|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001|doi-broken-date=2019-01-15}} |

||

* {{Cite |

* {{Cite journal|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1861|title=Beaufort, John, marquess of Dorset and marquess of Somerset (c. 1371–1410)|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|date=2004b|website=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|archive-url=https://archive.vn/kugdh|archive-date=9 January 2018|dead-url=no|access-date=9 January 2018|subscription=yes|ref=harv|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001|doi-broken-date=2019-01-15}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|date=2006|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19921-119-7|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461|last=Harriss|first=G. L.|date=2006|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19921-119-7|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Hicks|first=M. A.|title=Warwick the Kingmaker|year=2002|publisher=Blackwell|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-47075-193-0|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Hicks|first=M. A.|title=Warwick the Kingmaker|year=2002|publisher=Blackwell|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-47075-193-0|ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 170: | Line 170: | ||

* {{cite book|title=Fifteenth-century England, 1399–1509: Studies in Politics and Society|last=Pugh|first=T. B.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1972|isbn=978-0-06491-126-9|location=Manchester |pages=86–128|chapter=The Magnates, Knights and Gentry|ref=harv|editor1-last=Chrimes|editor1-first=S. B.|editor2-last=Ross|editor2-first=C. D.|editor3-last=Griffiths|editor3-first=R. A.}} |

* {{cite book|title=Fifteenth-century England, 1399–1509: Studies in Politics and Society|last=Pugh|first=T. B.|publisher=Manchester University Press|year=1972|isbn=978-0-06491-126-9|location=Manchester |pages=86–128|chapter=The Magnates, Knights and Gentry|ref=harv|editor1-last=Chrimes|editor1-first=S. B.|editor2-last=Ross|editor2-first=C. D.|editor3-last=Griffiths|editor3-first=R. A.}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=The Staffords, Earls of Stafford and Dukes of Buckingham: 1394–1521|last=Rawcliffe|first=C.|date=1978|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-52121-663-0|location=Cambridge|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|title=The Staffords, Earls of Stafford and Dukes of Buckingham: 1394–1521|last=Rawcliffe|first=C.|date=1978|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-52121-663-0|location=Cambridge|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{Cite |

* {{Cite journal|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26207;jsessionid=1EB205D43F2F9221C2F2666C6E9359B9|title=Stafford, Humphrey, first duke of Buckingham (1402–1460)|last=Rawcliffe|first=C.|date=2004|website=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|archive-url=https://archive.vn/P2GRF|archive-date=5 January 2019|dead-url=no|access-date=5 January 2019|ref=harv|subscription=Yes|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001|doi-broken-date=2019-01-15}} |

||

* {{cite journal|last=Reeves|first= A. C.|year=1972|title=Some of Humphrey Stafford's Military Indentures|journal=Nottingham Medieval Studies|volume=16|pages=80–91|oclc=941877294|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal|last=Reeves|first= A. C.|year=1972|title=Some of Humphrey Stafford's Military Indentures|journal=Nottingham Medieval Studies|volume=16|pages=80–91|oclc=941877294|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Ross|first=C. D.|title=The Yorkshire Baronage, 1399–1436|date=1952|degree=Unpublished D.phil|publisher=University of Oxford|url=|doi=|ref=harv}} |

* {{Cite thesis|last=Ross|first=C. D.|title=The Yorkshire Baronage, 1399–1436|date=1952|degree=Unpublished D.phil|publisher=University of Oxford|url=|doi=|ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

* {{cite book|title=British Drama 1533–1642: A Catalogue, 1609–1616|volume=VI|last2=Richardson|first2=C.|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2015|isbn=978-0-19873-911-1|location=Oxford|ref=harv|last1=Wiggins|first1=M.}} |

* {{cite book|title=British Drama 1533–1642: A Catalogue, 1609–1616|volume=VI|last2=Richardson|first2=C.|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2015|isbn=978-0-19873-911-1|location=Oxford|ref=harv|last1=Wiggins|first1=M.}} |

||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Stansfield|first=M. M. N.|title=The Holland family, Dukes of Exeter, Earls of Kent and Huntingdon, 1352–1475|date=1987|degree=D.Phil|publisher=University of Oxford|ref=harv}} |

* {{Cite thesis|last=Stansfield|first=M. M. N.|title=The Holland family, Dukes of Exeter, Earls of Kent and Huntingdon, 1352–1475|date=1987|degree=D.Phil|publisher=University of Oxford|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{Cite |

* {{Cite journal|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-13518|title=Holland, Edmund, seventh earl of Kent (1383–1408)|last=Stansfield|first=M. M. N.|date=2004|website=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|subscription=yes|archiveurl=https://archive.today/20180303133130/http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-13518|access-date=3 March 2017|archive-date=3 March 2018|deadurl=no|ref=harv|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001|df=|doi-broken-date=2019-01-15}} |

||

* {{Cite book|title=Dictionary of National Biography|last=Tait|first=J.|publisher=Smith, Elder & co.|year=1898|oclc=1070754020|editor-last=Lee|editor-first=S.|volume=53|location=London|chapter=Stafford, Humphrey, first Duke of Buckingham (1402–1460)|pages=451–454|ref=harv}} |

* {{Cite book|title=Dictionary of National Biography|last=Tait|first=J.|publisher=Smith, Elder & co.|year=1898|oclc=1070754020|editor-last=Lee|editor-first=S.|volume=53|location=London|chapter=Stafford, Humphrey, first Duke of Buckingham (1402–1460)|pages=451–454|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{Cite book|title=The Bones of a King: Richard III|author-last1=The Greyfriars Research Team|author-last2=Kennedy|author-last3=Foxhall|author-first2=M.|author-first3=L.|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|year=2015|isbn=978-1-11878-314-6|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

* {{Cite book|title=The Bones of a King: Richard III|author-last1=The Greyfriars Research Team|author-last2=Kennedy|author-last3=Foxhall|author-first2=M.|author-first3=L.|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|year=2015|isbn=978-1-11878-314-6|location=Oxford|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=H. M. |title=An Upwardly Mobile Medieval Woman: Juliana of Warwick |journal=Medieval Prosopography |date=1997 |volume=18 |pages=109122 |ref=harv |oclc=956033208}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=H. M. |title=An Upwardly Mobile Medieval Woman: Juliana of Warwick |journal=Medieval Prosopography |date=1997 |volume=18 |pages=109122 |ref=harv |oclc=956033208}} |

||

* {{cite journal|last=Walker|first= S. |

* {{cite journal|last=Walker|first= S.|year=1976|title=Widow and Ward: The Feudal Law of Child Custody in Medieval England|journal=Feminist Studies|volume=3|pages=107–118|oclc= 972063595|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Wolffe|first=B. P.|title=The Royal Demesne in English History: The Crown Estate in the Governance of the Realm from the Conquest to 1509|year=1971|publisher=Ohio University Press|location=Athens|oclc=277321|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Wolffe|first=B. P.|title=The Royal Demesne in English History: The Crown Estate in the Governance of the Realm from the Conquest to 1509|year=1971|publisher=Ohio University Press|location=Athens|oclc=277321|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Zimbalist|first=B.|editor-last1=Cotter-Lynch|editor-first1=M.|editor-last2=Herzog|editor-first2=B.|title=Reading Memory and Identity in the Texts of Medieval European Holy Women|date=14 March 2012|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|location=New York|isbn=978-1-13706-483-7|pages=105–134|chapter=Imitating the Imagined: Clemence of Barking's Life of St. Catherine|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Zimbalist|first=B.|editor-last1=Cotter-Lynch|editor-first1=M.|editor-last2=Herzog|editor-first2=B.|title=Reading Memory and Identity in the Texts of Medieval European Holy Women|date=14 March 2012|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|location=New York|isbn=978-1-13706-483-7|pages=105–134|chapter=Imitating the Imagined: Clemence of Barking's Life of St. Catherine|ref=harv}} |

||

Revision as of 06:21, 15 January 2019

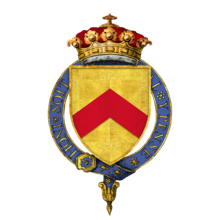

Humphrey Stafford | |

|---|---|

| The Duke of Buckingham | |

Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, by William Bond, after Joseph Allen. | |

| Born | December 1402 |

| Died | 10 July 1460 (aged 57) |

| Buried | Gray Friars, Northampton |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Anne Neville |

| Issue | Humphrey Stafford, Earl of Stafford Sir Henry Stafford Edward Stafford Katherine Stafford George Stafford William Stafford John Stafford, 1st Earl of Wiltshire Joan (or Joanna) Stafford Anne Stafford Margaret Stafford |

| Father | Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford |

| Mother | Anne of Gloucester |

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 6th Earl of Stafford, KG (1402 –10 July 1460) was an English nobleman and a military commander in both the Hundred Years' War and the Wars of the Roses. Through his mother he had royal blood as a great-grandson of King Edward III, and from his father, he inherited the earldom of Stafford at an early age. By his marriage to a daughter of Ralph, Earl of Westmorland, Humphrey was not only related to the powerful Neville family but many of the leading aristocratic houses of the time. He joined the English campaign in France with King Henry V in 1420, and following Henry V's death two years later he became a councillor for the new King, the nine-month-old Henry VI. Stafford acted as a peacemaker during the partisan, factional politics of the 1430s, when Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester vied with Cardinal Beaufort for political supremacy. Stafford also took part in the eventual arrest of Gloucester in 1447.

Stafford returned to the French campaign during the 1430s, and, as a result of his loyalty and years of service, he was elevated from Earl of Stafford to Duke of Buckingham. Around the same time, his mother died. As much of his estate—as her dower—had previously been in her hands, Humphrey went from having a reduced income in his early years to being one of the wealthiest and most powerful landowners in England. His lands stretched across much of the country, ranging from East Anglia to the Welsh border. Being such an important figure in the localities was not without its dangers, and for some time he feuded violently with Sir Thomas Malory in the the Midlands.

Following his return from France, Stafford remained in England for the rest of his life, serving King Henry. He acted as both King's bodyguard and chief negotiator Jack Cade's rebellion of 1450 and helped suppress it. Similarly, when the King's cousin, Richard, Duke of York, rebelled two years later, Stafford investigated York's followers. In 1453, the King became ill and sank into a catatonic state; law and order broke down further, and the country slid towards civil war. When armed conflict broke out in 1455 Stafford fought for the King in the first battle of the Wars of the Roses, at St Albans in 1455, where they were both captured by the Yorkists. Stafford spent much of the last few years of his life attempting to mediate between the Yorkist and Lancastrian factions, the latter by now headed by Henry's Queen, Margaret of Anjou. Partly due to a personal feud with a leading Yorkist—the Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick—Stafford eventually declared for his King. The weight Stafford could throw behind the royal campaign was responsible for Richard, Duke of York's defeat in 1459, which drove York into exile. On the rebels' return the following year they attacked the royal army at Northampton. Acting as the King's personal guard, in the ensuing struggle Stafford was killed, and the King was again taken prisoner. Stafford's eldest son had died of plague two years earlier, so the Buckingham dukedom descended to Stafford's five-year-old grandson, Henry, a ward of the King until he came of age in 1473.

Background and youth

Humphrey Stafford was born in Stafford sometime in December 1402.[1] He was the only son of Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford, and Anne of Gloucester, who was the daughter of Edward III's youngest son Thomas of Woodstock.[1] This gave Humphrey royal blood, and made him a second cousin to the then-King, Henry IV.[2]

When Humphrey was less than a year old, his father was killed fighting for King Henry against the rebel Henry Hotspur at the Battle of Shrewsbury, on 21 July 1403,[1] and Humphrey became 6th Earl of Stafford.[3] With the earldom came a large estate with lands in more than a dozen counties. Before his mother Anne had married Edmund she had previously been married to his older brother, Thomas. As a result, she had accumulated two dowries,[note 1] each comprising a third of the Stafford estates. She occupied these lands for the next twenty years.[7] Humphrey, therefore, received a reduced income of less than £1,260 a year until he was sixteen. His mother could not, by law, be his guardian,[8] so Humphrey became a royal ward on his father's death, and was put under the guardianship of Henry IV's queen, Joan of Navarre.[1] His minority was to be a long one, lasting the next twenty years.[9]

Early career

Although Stafford received a reduced inheritance, as historian Carol Rawcliffe has put it, "fortunes were still to be made in the French wars"; and, like generations of Staffords before him, he assumed the profession of arms.[1] He fought with Henry V on the 1420 campaign and was knighted on 22 April the following year.[1] Henry V caught a fatal dose of dysentery—still on campaign—on 31 August 1422, and Stafford was present as he died.[10] He joined the entourage that returned to England with the royal corpse.[11] When Stafford was later asked by the royal council if the King had left any final instructions regarding the governance of Normandy, Stafford claimed that he had been too upset at the time to be able to remember.[12] Stafford was himself still a minor at this time,[12] although parliament soon granted him livery of his father's estate,[note 2] which allowed him full possession. They did so based on Stafford's claim that Henry V had verbally promised him this before Henry died, and Stafford did not have to pay a fee into the Exchequer on attaining his inheritance as was the norm.[16]

The new King, Henry VI, was still only a baby, so the lords decided that the dead King's brothers—John, Duke of Bedford and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester—would have to be prominent in this minority government. Bedford, it was decided, would rule as regent in France, whilst Gloucester would be chief councillor (although not protector) in England. Stafford became a member of the new royal council on its formation.[17] It first met in November 1422[18] and Stafford was to be an assiduous attender for the next three years.[19] By 1424, the rivalry between Gloucester—who had made repeated claim to deserve the title of Protector—and the Bishop of Winchester, Henry Beaufort,[20] as the de facto head of council had become outright and frequent conflict. Although Stafford seems to have personally favoured the interests of Gloucester in the latter's struggle for supremacy over Beaufort,[12] the earl attempted to be a moderating influence.[1] For example, in October 1425, Stafford, with the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Portuguese Duke of Coimbra, helped to negotiate an end to a burst of violence that had erupted in London between the two rivals' followers.[21] However, in 1428, when Gloucester again demanded an increase in his power, Stafford was one of the councillors who personally signed an "outspoken statement"[12] to the effect that Gloucester's position had been formulated six years earlier, would not change now, and that in any case the King would attain his majority within a few years.[12] Stafford was also chosen by the council to inform Beaufort—now a Cardinal—that he was to absent himself from Windsor until it was decided if he could carry out his traditional duty of Prelate to the Order of the Garter now that the Pope had promoted.[12]

Stafford himself was made a knight of the Order of the Garter in April 1429,[22] and the following year travelled to France with the King for French coronation, escorting him through the war-torn countryside.[23] The earl was appointed Lieutenant-General of Normandy,[24] Governor of Paris, and Constable of France over the course of his next two years of service there.[1] Apart from one occasion in November 1430 when he and Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter took the English army to support Philip, Duke of Burgundy, Stafford's primary military role at this time was carrying out defending Paris and its environs.[25] He also attended the interrogation of Joan of Arc in Rouen in 1431; at some point during these proceedings, a contemporary alleged, Stafford attempted to stab her and had to be physically restrained.[26][1]

On 11 October 1431 the King created Stafford Count of Perche, which was a province in English-occupied Normandy; he was to hold the title until the English finally withdrew from Normandy in 1450.[27][28] The county was valued at 800 marks per annum,[29][note 3] although the historian Michael Jones has suggested that as this was an area of almost constant warfare, in real terms "the amount of revenue that could be extracted ... must have been considerably lower".[27] Since Perche was a frontier region, in a state of almost constant conflict,[31] whatever income the estate generated was probably immediately re-invested in its defence.[32]

In England, the King's minority ended in 1436. In preparation for his personal rule, the council reorganised Henry's Lancastrian estates to be under the control of local magnates. This gave Stafford responsibility for much of the north Midlands and Derbyshire, the largest single chunk of the duchy that to be delegated among the nobility.[33] This put the royal affinity—those men retained directly by the Crown in order to provide a direct link between the King and the localities[34]—at his command.[35]

Estates

The centrepiece of Stafford's estates, and his own caput, was Stafford Castle. Here he maintained a permenant staff of at least forty people, as well as a large stable, and it was perfectly placed for recruiting retainers in the Welsh Marches, Staffordshire, and Cheshire.[36] He also had manor houses at Writtle and Maxstoke, which he had purchased as part of most of the estates of John, Lord Clinton;[37] they were useful when the royal court was in Coventry.[38] Likewise, he made his base at Tonbridge Castle when he was acting as Warden of the Cinque Ports or on commission in Kent.[39] His marcher castles—Caus, Hay, Huntingdon, and Bronllys—had, by the 1450s, generally fallen into disrepair, and his other border castles, such as Brecon and Newport, he rarely used.[39] Stafford's Thornbury manor was convenient for Bristol and was a stopping point to and from London.[39]

Stafford's mother's death in 1438 transformed his fiscal position. He now received the remainder of his father's estates—worth about £1,500—and his mother's half of the de Bohun inheritance, which was worth another £1,200. The latter also included the earldom of Buckingham, itself worth £1,000, and, overall, Stafford had become one of the greatest landowners in England overnight.[1] "His landed resources matched his titles", explained Albert Compton-Reves, scattered as they were throughout England, Wales and Ireland,[40] and it is likely that only the King and the Richard, Duke of York were wealthier.[41] One assessment of his estates suggests that, by the late 1440s, his income was over £5,000 per annum,[42] and K.B. McFarlane estimated Stafford's total potential income from land to have been £6,300 gross annually, at its peak between 1447 and 1448.[43][44] On the other hand, the actual yield may have been far lower; possibly as low as £3,700:[45] Rents, for example, were often difficult to collect. Even a lord of the status of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, for example, owed Stafford over £100 in unpaid rent for the manor of Drayton Bassett in 1458.[46] In the 1440s and 1450s, Stafford's Welsh estates were particularly notable for both their rent arrears and public disorder.[47] Further—and like most nobles of the period—he substantially overspent, possibly by as much as £300 a year.[48]

Affinity and problems in the localities

In the late medieval period, all great lords created an affinity between themselves and groups of supporters, who often lived and travelled with them for purposes of mutual benefit and defence,[49] and Humphrey Stafford was no exception. These men were generally his estate tenants, who could be called upon when necessary for soldiering, as well as other duties,[50] and often retained by indenture.[note 4] In the late 1440s his immediate affinity was at least ten knights and twenty-seven esquires, mainly drawn from Cheshire.[44] By the 1450s—a period beginning with political tension and ending with civil war—Stafford retained men specifically "to sojourn and ride" with him.[52] His affinity was probably composed along the lines laid out by royal ordinance at the time which dictated the nobility should be accompanied by 240 men, including "forty gentlemen, eighty yeomen and a variety of lesser individuals",[44] suggested T. B. Pugh, although in peacetime Stafford would have required far fewer. It was directly due to the political climate that this increased, especially after 1457.[53] Stafford's household more generally has been estimated at around 150 people by about 1450.[54] It has been estimated that maintaining both his affinity and household cost the duke over £900 a year.[44]

Along with Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, Stafford was the major magnatial influence in Warwickshire,[55] so when Warwick left for a lengthy tour of duty in France, in 1437, Stafford became the centre of regional power stretching from Warwickshire to Derbyshire.[37] He was sufficiently involved in the royal court and government that he was often unable to attend to the needs of his region.[1] This caused him local difficulties; on 5 May 1430 a Leicestershire manor of Stafford's was attacked[56] and he faced problems in Derbyshire in the 1440s, although there, Helen Castor has said, Stafford "made no attempt to restore peace, nor made any attempt to intervene at all".[57] Stafford also had major estates on the Welsh Marches. This area was prone to regular lawlessness and particularly occupied his time as a royal justice.[1] One of the most well-known disputes Stafford had with his local gentry was in his midlands heartlands. This was with Sir Thomas Malory. On 4 January 1450, Malory, with twenty-six other armed men, waited for Stafford near Coombe Abbey woods—near the duke's Newbold estate—intending to ambush him.[58] Stafford fought back, repelling Malory's small force with sixty yeomenry.[59] In another episode, Malory stole deer from the duke's park at Caludon.[60] Stafford personally arrested Malory on 25 July 1451.[61] The duke also ended up in a dispute with William Ferrers of Staffordshire, even though the region was the centre of Stafford's authority and where he may have expected to be strongest. Ferrers had recently been appointed to the county King's Bench and attempted to assert political control over the county as a result.[62] Following Cade's rebellion in 1450, his park at Penshurst was attacked by men "concealing their faces with long beards and charcoal-blackened faces, calling themselves servants of the queen of the fairies".[63] Towards the end of the decade, not only was Stafford unable to prevent feuding amongst the local gentry, but his own affinity was in discord.[64] This may in part be due to the fact that at this time Stafford was not spending much of his time in the Midlands. Rather, he preferred to stay close to London and the King, dwelling either at his manors of Tonbridge or Writtle.[65]

Later career

In July 1436, Stafford, accompanied by Gloucester, the Duke of Norfolk, and the Earls of Huntingdon, Warwick, Devon, and Ormond, returned to France again with an army of nearly 8,000 men.[66] Although the expedition's purpose was to end the siege of Calais by Philip, Duke of Burgundy, the Burgundian's had withdrawn before they arrived,[67] leaving behind a quantity of cannon for the English to seize.[68] Subsequent peace talks in France occupied Stafford throughout 1439, and in 1442 he was appointed Captain of Calais[1] and Risbanke, and was indented to serve for the next decade.[69] Prior to his departure for Calais in September 1442, the garrison had revolted and seized the Staple's wool in lieu of unpaid wages. Stafford received a pledge from the council that if such a situation arose again during his tenure, he would not be held responsible.[70] In light of the secrecy that cloaked Stafford's appointment in 1442, suggests David Grummitt, it is possible that the revolt had actually been staged by his servants to ensure that Stafford "had entry [to Calais] on favourable terms".[71] Stafford himself emphasised the need to restore order there in his original application for the office.[72] He also received another important allowance, being granted permission to export gold and jewels (up to the value of £5,000 per trip) for his use in France, even though the export of bullion was illegal at the time.[73] He served the full term of his appointment as Calais captain, leaving office in 1451[1]

Around 1435, Buckingham had been granted the Honour of Tutbury, which he held until 1443. Then, says Ralph Griffiths, he proceeded to "hand it over to the son of one of his own councillors".[74] Other offices he held around this time included Seneschal of Halton from 1439, and Lieutenant of the Marches from 1442 to 1451. Stafford became less active on the council around the same time.[75] He became Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Constable of Dover Castle and Constable of Queenborough, on the Isle of Sheppey, in 1450. He again represented the Crown during further peace talks with the French in 1445 and 1446.[1]

Buckingham rarely visited Calais, however. Factional strife had continued intermittently between Beaufort and Gloucester, and Buckingham—who had also been appointed Constable of England—was by now firmly in the Beaufort camp.[48][76] In 1442, he had been on the committee that investigated and convicted Gloucester's wife, Eleanor Cobham, of witchcraft,[48] and five years later he arrested the duke at Bury St Edmunds on 18 February 1447 for treason.[1] Like many others, Buckingham profited substantially from Gloucester's fall: when the latter's estates were divided up, the "major prizes"[77] went to the court nobility.[77]

In September 1444, as reward for his loyal and continuous service to the Crown, he was created Duke of Buckingham.[78] By then he was already describing himself as "the Right Mighty Prince Humphrey Earl of Buckingham, Hereford, Stafford, Northampton and Perche, Lord of Brecknock and Holdernesse".[79] Three years later he was granted precedence over all English dukes not of royal blood.[80] Despite his income and titles he was consistently heavily out of pocket. Although rarely in Calais, he was responsible for ensuring the garrison was paid, and it has been estimated that when he resigned and returned from the post in 1450, he was owed over £19,000 in back wages.[81] This was such a large amount that he was granted the wool trade tax from the port of Sandwich, Kent until it was paid off.[73] Hs other public offices also forced him to spend over his annual income, and he had household costs of over £2,000.[1] He was also a substantial creditor to the government, which was perennially short of cash.[82]

With the outbreak of Jack Cade's rebellion, Buckingham summoned about seventy of his tenants from Staffordshire to accompany him whilst he was in London in May 1450.[83] He was one of the lords commissioned to arrest the rebels as part of a forceful government response on 6 June 1450, and he acted as a negotiator with the insurgents at Blackheath ten days later.[84] However, the promises that Buckingham made on behalf of the government were not kept, and Cade's army invaded London.[85] After the eventual defeat of the rebellion, Buckingham headed an investigatory commission designed to "placate" rebellious Kent,[86] and in November that year he rode noisily through London—with a retinue of around 1,500 armed men—with the King and other peers, in a "demonstration of official power"[87] intended to deter potential troublemakers in the future.[87] Following the rebellion, Buckingham and his retinue often acted as a bodyguard to the King.[88]

Wars of the Roses

From 1451, the King's favourite, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, had become chief councillor,[89] and Buckingham supported Somerset's government.[90] At the same time, he tried to maintain peace between Somerset and York, who by now was Somerset's bitter enemy.[91] When York rebelled in 1452 and confronted the King with a large army at Dartford, Buckingham was again a voice of compromise, and, since he had contributed heavily towards the size of the King's army, his voice was heeded.[92] Buckingham took part in a peace commission on 14 February that month in Devon, which prevented Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon from joining York at Dartford.[93] A year later, in August 1453, King Henry became ill, and slipped into a catatonic state; government slowly broke down. At Christmas, Buckingham personally presented the King's son—the newly-born Edward, Prince of Wales—to the King. But Henry "gave no manner answer".[94] Buckingham took part in the council meeting which resulted in the arrest and subsequent year-long imprisonment of the Duke of Somerset.[91] In the February 1454 parliament Buckingham was appointed Steward of England, although Griffiths has called this position "largely honorific".[95] This parliament also appointed York Protector of the Realm from 27 March 1454.[96] Buckingham supported York's protectorate, attending York's councils more frequently than most of his fellow councillors.[97] The King recovered his health in January 1455, and, soon after, Somerset was released—or may have escaped—from the Tower. A contemporary commented how Buckingham "straungely conveied" Somerset from prison,[97] but it is uncertain whether this was as a result of the King ordering his release or whether Somerset escaped with Buckingham's connivance.[98] Buckingham may well by now have been expecting war to break out, because the same year he ordered the purchase of 2,000 cognizances—the 'Stafford knot'[99]—even though strictly the distribution of livery was illegal.[100]

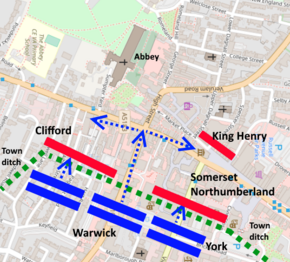

Battle of St Albans

Following the King's recovery, York was either dismissed from or resigned his Protectorship, and together with his Neville allies, withdrew from London to their northern estates. Somerset—in charge of government once again—summoned a Great Council to meet in Leicester on 22 May 1455. The Yorkists believed they would be arrested or attainted at this meeting. As a result, they gathered a small force and marched south. The King, with a smaller force[101] that nonetheless included important nobles such as Somerset, Northumberland, Clifford and Buckingham and his son Humphrey, Earl of Stafford,[102] was likewise marching from Westminster to Leicester, and in the early morning of 22 May, royal scouts reported the Yorkists as being only a few hours away. Buckingham urged that they push on to St Albans—in order that the King might dine[103]—which was not, however, particularly easy to defend.[note 5] Buckingham also assumed that York would want to parley before launching an assault on the King, as he had in 1452. The decision to head for the town and not make a stand straight away may have been a tactical error.[101] The Lancastrians "strongly barred and arrayed for defence".[101] The King was lodged in the town and York, with the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick, encamped to the south.[104] Negotiations commenced immediately. York demanded that Somerset be released into his custody, and possibly because of this, the King replaced Somerset as Lord High Constable with Buckingham,[105] making Somerset his subordinate.[103] In that capacity, Buckingham became the King's personal negotiator—Armstrong suggests because he was well known to be able to "concede but not capitulate"[102]—and received and responded to the Yorkists' messengers.[106] His strategy was to play for time,[107] both to prepare the town's defences[108] and to await the arrival of loyalist bishops, who could be counted on to bring the moral authority of the church to bear on the Yorkists.[108] Buckingham received at least three Yorkist embassies, but the King—or Buckingham—refused to give in to the main Yorkist demand, that Somerset be surrendered to them.[109] Buckingham may have hoped that repeated negotiations would deplete the Yorkists' zest for battle, and likewise delay long enough for reinforcements to arrive;[110] his confidence in how reasonable the Yorkists would be[111] was misplaced.[102] To achieve this, Buckingham made what John Gillingham described as an "insidiously tempting suggestion"[112] that the Yorkists mull over the King's responses in Hatfield or Barnet overnight.[112]

The Yorkists realised what Buckingham—"prevaricating with courtesy", says Armstrong[113]—was trying to do and battle commenced while negotiations were still taking place: Richard, Earl of Warwick launched a surprise attack at around ten o'clock in the morning.[114][110] Buckingham commanded the King's army of 2,500 men, although his coordination of the town's defence was problematic, giving the initiative to the Yorkists.[112] Although the defences that Buckingham had organised successfully checked the Yorkists' initial advance,[115] Warwick took his force through gardens and houses to attack the Lancastrians in the rear. The battle was soon over, and had lasted between half an hour[110] to an hour[115] with only about 50 casualties. However, among the dead were senior Lancastrian captains, and included Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland and Lord Clifford.[note 6] Buckingham himself was wounded[106]—hit three times "in the vysage"[119] by arrow fire[116]—and sought sanctuary in the abbey.[120][note 7] His son had been badly wounded.[note 8] A chronicler reported that some Yorkist soldiers, intent on looting, entered the abbey to kill Buckingham, but that the duke was saved by York's personal intervention.[102] In any case, Buckingham was probably captured with the King,[122] although he was still able to reward ninety of his retainers from Kent, Sussex[85] and Surrey. It is not known for certain whether these men had actually fought with him at St Albans; as K. B. McFarlane points out, many retinues did not arrive in time to fight.[123]

Last years

York now had the political upper hand, made himself Constable of England and kept the King as a prisoner, returning to the role of Protector when Henry became ill again.[96] Buckingham swore to "draw the lyne" with York,[124] and supported his second protectorate, although losing Queen Margaret's favour as a result. A contemporary wrote that in April 1456 the duke returned to his Writtle manor, not looking "well plesid".[97] Buckingham played an important role at the October 1456 Great Council in Leicester.[125] Here, with other lords, he tried to persuade the King to impose a settlement, and at the same time declared that anyone who resorted to violence would receive "ther deserte"[126]—which included any who attacked York.[1]

In 1459, with other lords, he renewed his oath of loyalty to the King and Prince of Wales.[127] Until this point he had been a voice of restraint within the King's faction–possibly even on the queen herself.[128] But he had been restored to her favour that year and—as she was the de facto leader of the party—his realignment was decisive enough that it ultimately hastened the outbreak of hostilities again. Buckingham may also have been partially motivated by financial needs,[129] and encouraged to do so by those retainers reliant on him.[130] He had a bigger retinue than almost any other noble in England[129] and was still the only one who could match York in power and income.[131] This was demonstrated at the Battle of Ludford Bridge in October 1459, where his army played a decisive part in the defeat of the Yorkist forces.[132][129] Following their defeat, York and the Neville earls fled Ludlow and went into exile; York to Ireland, the earls to Calais. They were attainted at the Coventry parliament later that year, and their estates distributed amongst the Crown's supporters. Buckingham was rewarded by the King with extensive grants from the estates of Sir William Oldhall,[1] probably worth over £800 per annum.[133] With York in exile, Buckingham was granted custody of York's wife, Cecily, Duchess of York, whom, a chronicler reports, he treated harshly in her captivity.[133]

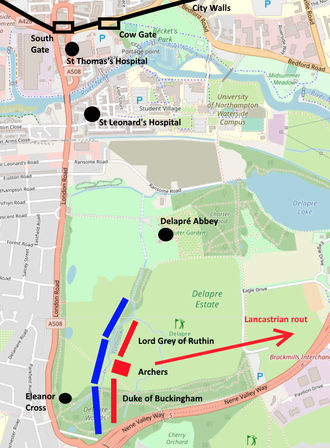

Death at Northampton

From the moment the Duke of York and the Neville earls left England it was obvious to the government that they would return; the only question was when. After a series of false alarms in early 1460, they eventually did so in June, landing at Sandwich, Kent.[134] They immediately marched on, and entered, London; the King, with Buckingham and other lords, was in Coventry, and on hearing of the earls' arrival, moved the court to Northampton.[135] The Yorkists left London and marched to the King; they were accompanied by the Papal legate Francesco Coppini. In the lead up to the Battle of Northampton, the Earls of Warwick and March sent envoys to negotiate,[135] but Buckingham—once again the King's chief negotiator,[136] and backed by his son-in-law, the Earl of Shrewsbury and Lords Beaumont and Egremont[135]—was no longer conciliatory.[135] Buckingham denied the Yorkists' envoys' repeated requests for an audience with Henry,[137] denouncing the earls: "the Earl of Warwick shall not come to the King's presence and if he comes he shall die".[138] Buckingham condemned the bishops who had accompanied the Yorkist army as well, telling them that they were not men of peace, but men of war, and there could now be no peace with Warwick.[138] Personal animosity as much as political judgment was probably responsible for Buckingham's attitude, possibly the result of Warwick's earlier rent evasion.[132] Buckingham's influential voice was chief among those demanding a military response to Warwick and March;[139] the duke may also have misinterpreted the Yorkists' requests to negotiate as a sign of weakness,[140] and probably saw the coming battle as an opportunity to settle scores with Warwick. But Buckingham misjudged both the size of the Yorkist army—which outnumbered that of the King[135]—and the loyalty of the Lancastrian army.[140] Whatever plans Buckingham had, says Carol Rawcliffe, they "ended abruptly" on the battlefield.[132]

Buckingham's men dug in outside Northampton's southern walls, and fortified behind a tributary of the River Nene, close to Delapré Abbey.[141] Battle was joined early on 10 July 1460. Although it was expected to be a drawn-out affair—due to the near-impregnability of the royal position— it was shortened considerably when Lord Grey of Ruthin turned traitor to the King.[140] Grey "welcomed the Yorkists over the barricades" on the Lancastrian left wing[136] and ordered his men to lay down arms, allowing the Yorkists access to the King's camp. Within half an hour, the battle was over.[140] By 2:00 pm, Buckingham, the Earl of Shrewsbury, Lord Egremont and Viscount Beaumont, had all been killed, possibly by a force of Kentishmen.[140] The duke was buried shortly after at Grey Friars Abbey in the Northampton.[1]

Buckingham had named his wife Anne sole executrix of his will. She was instructed to provide 200 marks to any clergy who attended his funeral, with the remainder being distributed as poor relief. She was also to organise the establishment of two chantries in his memory, and, says G. L. Harriss, he left "exceedingly elaborate" instructions for the foundation of a college in Pleshy.[142]

Character

Humphrey Stafford has been described as something of a hothead in his youth,[143] and later in life he was a staunch anti-Lollard. It was probably connected to this that Sir Thomas Malory attempted his assassination[144] around 1450—if indeed he did, as the charge was never proved. Buckingham did not lack the traits traditionally expected of the nobility in this period of the time, particularly, in dispute resolution, that of resorting to violence as a first rather than last resort. For instance, in September 1429, following an altercation with his brother-in-law the Earl of Huntingdon, he arrived at parliament "armed to the teeth".[145] On the other hand, he was also a literary patron: Lord Scrope presented him with a copy of Christine de Pizan's Epistle of Othea, demonstrating his position as a "powerful and potentially powerful patron",[146] and its dedicatory verse to Buckingham is particularly laudatory.[147] On Buckingham's estates—especially on the Welsh marches—he has been described as a "harsh and exacting landlord" in the lengths he went to in maximising his income.[148] He was also competent in his land deals, and seems never—unlike some contemporaries—to have had to sell land to stay solvent.[149]

G. L. Harriss noted that, although he died a staunch Lancastrian, he never showed any personal dislike of York in the 1450s, and that his personal motivation throughout the decade was loyalty to the Crown and keeping the peace between his peers.[150] Rawcliffe has suggested that although he was inevitably going to be involved in the high politics of the day, Buckingham "lacked the necessary qualities ever to become a great statesman or leader ... [he] was in many ways an unimaginative and unlikeable man".[151] On the latter quality, Rawcliffe points to his reputation as a harsh taskmaster on his estates and his "offensive behaviour"[151] towards Joan of Arc. Further, she says, his political judgement could be clouded by his attitude.[151] His temper, she says, was "ungovernable".[1]

Aftermath

Michael Hicks has noted that Buckingham was one of the few Lancastrian loyalists who was never accused by the Yorkists of being an "evil councillor",[152] even though he was—in Hicks's words—"the substance and perhaps the steel within the ruling regime".[152] Buckingham's eldest son and heir Humphrey predeceased his father, dying of plague in 1458. As such, the Stafford titles, wealth and lands descended to his son—Buckingham's grandson—Henry Stafford.[132] Although Buckingham was not attainted when the Duke of York's son, the Earl of March, took the throne as King Edward IV in 1461, Buckingham's grandson Henry became a royal ward, which gave the King control of the Stafford estates during the young duke's minority.[153] Henry Stafford entered into his estates in 1473 but was executed by Edward's brother Richard—by then King, and against whom Henry had rebelled—in November 1483.[154]

Family

Humphrey Stafford married Lady Anne Neville, daughter of Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland and Lady Joan Beaufort (Westmorland's second wife), at some point prior to 18 October 1424.[1] Anne Neville was a literary patron in her own right, also receiving a dedication in a copy of Scrope's translated Othea,[146] and on her death in 1480 left many books in her will.[155] They probably had twelve children, possibly consisting of seven sons (only three of whom survived to adulthood) and five daughters.[1] At least three sons died young (Edward, George and William, the latter two twins). The seventh son has gone unremarked in the sources.[156] Elizabeth and Margret are known not to have married.[157] However, sources conflict over the precise details of the Staffords' progeny; as Harald Kleinschmidt has noted, "determining the precise age of a person was difficult because birth dates were rarely recorded before the nineteenth century and because baptism was usually dated in terms of the day and the month, but not of the year in which it had occurred".[158] Further, says Hugh M. Thomas, there is an "inherent difficulty of calculating birth dates from life events" such as marriages.[159][note 9]

The marriages Buckingham arranged for his children were structured around strengthening his ties to the Lancastrian royal family. Of particular importance were the marriages of two of his sons. They married into the Beaufort family, who were descended from the illegitimate children of John of Gaunt[164] and thus of royal blood.[165] His eldest son, Humphrey had married Margaret Beaufort. She was the daughter of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, and Eleanor Beauchamp. Margaret and Humphrey's son was thus Buckingham's eventual heir.[1] A second link to the Beaufort family was between Buckingham's second son, Sir Henry Stafford (c. 1425–1471), who was to be the third husband of Lady Margaret Beaufort, daughter of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, and Margaret Beauchamp. Margaret Beaufort had previously been married to Edmund Tudor, the eldest half-brother of Henry VI, and had given birth to the future King Henry VII two months after Edmund's death. She and Henry were childless.[166] Buckingham's third surviving son, John (died 8 May 1473) married Constance Green of Drayton,[166] who had previously been the duke's ward.[167] Humphrey Stafford assigned them the manor of Newton Blossomville at the time of their marriage.[168] John was created Earl of Wiltshire in 1470.[169]

The Duke of Buckingham's daughters made good (but for their father, expensive) marriages.[1] They married the heirs of the Earl of Oxford, Viscount Beaumont and of the Earl of Shrewsbury.[170] One daughter—possibly Anne (1446–1472)—had been proposed as the future consort to Louis XI of France,[1] which would have linked the French Crown again with the Lancastrian regime,[171] although she married Aubrey de Vere, son of John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, instead.[172] This marriage cost Buckingham 2,300 marks, and he "took a long even time to pay that".[173] In 1452, Joan (1442–1484) married William Beaumont. Margaret (1437–1476), married John Talbot. Buckingham had apparently promised to give them £1,000 but died before acting on the promise.[1][note 10]

Cultural references and portrayals

Buckingham was depicted, during his son's lifetime, as "mounted in battle array"—during the 1436 campaign against Burgundy—in the pictorial genealogy Beauchamp Pageant, which was probably compiled by Anne, Countess of Warwick, Warwick's widow, in 1480.[66]

T. L. Lustig has suggested that Thomas Malory, in his Morte d'Arthur, based the character of his Gawaine on Buckingham. Lustig suggests that Malory may have viewed the duke as being "peacemaker and warlord, warrior and judge"—qualities which the writer later ascribed to his Arthurian character.[143] Buckingham appears in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2 (c. 1591), in which his character conspires in the downfall and disgrace of Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester.[175]

Buckingham was probably the eponymous subject character of the early-seventeenth-century play, Duke Humphrey, which is now lost.[176]

Notes

- ^ The legal concept of dower had existed since the late twelfth century as a means of protecting a woman from being left landless if her husband died first. He would, when they married, assign certain estates to her—a dos nominata, or dower—usually a third of everything he was seised of. By the fifteenth century, the widow was deemed entitled to her dower.[4] Stafford's situation was not uncommon in the late middle ages: when the last Holland Earl of Kent Edmund inherited the title from his brother Thomas (who died childless), in 1404, the estates had to support the dowers of Edmund's mother Alice, his brother's widow, Joan Stafford, and his aunt, Elizabeth of Lancaster, Duchess of Exeter.[5] Edmund died in 1408; his wife then became the fourth dowager on the inheritance, and, there being no male heirs, it was broken up and divided amongst them and Edmund's five sisters.[6]

- ^ The feudal system was based on the premise that all land belonged to the king. What he held directly was the royal demesne, and that which was granted away was held on his behalf by tenants-in-chief.[13] If he then died without leaving an adult heir who could immediately receive his inheritance, the estates escheated (returned to the king).[14] The king would hold the estates until the heir (if any) reached his majority, at which point he would apply for livery of seisin: the right to enter his estates. Possession was usually obtained by paying a fine to the exchequer.[15]

- ^ A medieval English mark was an accounting unit equivalent to two-thirds of a pound.[30]

- ^ K. B. McFarlane uses the example of John of Gaunt to illustrate the wide variety of staff that could be indentured; Gaunt contracted with, among others, his surgeons, chaplains, clerk, falconer, cook, minstrels, heralds, and legal counsels.[51]

- ^ For example, it had no walls, only a defensible ditch, and access to the south of the main street was easily accessible.[101]

- ^ A contemporary chronicler observed how "when the said lords were dead, the battle was ceased".[116] The historian C. A. J. Armstrong suggested that this may indicate that the Lancastrian lords' deaths were less an accident of war and more an "act of private revenge on a few prominent individuals" by York and the Nevilles.[117][118]

- ^ The Earl of Wiltshire had also taken refuge with the King and Buckingham, but escaped as the Yorkists approached; he was reported to have fled dressed in the garb of a monk, discarding his armour as he went.[117][118]

- ^ Indeed, there were persistent rumours at the time that he had died either on the field or soon after of his wounds; however, he lived another three years, dying of plague in 1458.[121]

- ^ The children of the Buckinghams are a case in point. The American antiquarian, I. W. Dunham, writing in 1907, listed them as: Humphrey, Henry, John (later Earl of Wiltshire), Anne (married Aubrey de Vere), Joana (married Viscount Beaumont prior to 1461), Elizabeth, Margaret (born about 1435 and married Robert Dinham), Catherine (married John Talbot before 1467). However, Dunham does also place Humphrey as dying 1455 at the battle of St. Albans.[160] James Tait on the other hand, in his Dictionary of National Biography entry, agrees that they had 12 children ("seven sons (four of whom died young) and five daughters").[161] Tait lists the surviving sons as Humphrey (who was "gretly hurt" at St Albans "and died not long after"),[161] Henry and John. Tait lists daughters as Anne, Joanna, Elizabeth, Margaret and Catherine. Tait also notes that "about 1450 there was some talk of marrying one of Buckingham's daughters, probably the eldest, to the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XI".[161] Spellings too differed, as during this period, written English was intended to reflect the spoken language;[162] for instance—in the case of Buckingham's daughter—between the Anglo-Norman "Catherine" and the later medieval "Katherine".[163]

- ^ Anne lists her still-living children in her will of 1480: her "son Buckingham"—meaning her grandson Henry—and "my daughter Beaumond", "my son of Wiltshire", "my daughter of Richmond" and "my daughter Mountjoy".[174]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Rawcliffe 2004.

- ^ Griffiths 1979, p. 20.

- ^ Cokayne 1912, p. 389.

- ^ Kenny 2003, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Stansfield 1987, pp. 151–161.

- ^ Stansfield 2004.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 12.

- ^ Walker 1976, p. 104.

- ^ Harriss 2006, p. 524.

- ^ Matusiak 2012, p. 234.

- ^ Allmand 2014, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f Jacob 1993, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Wolffe 1971, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Lawler & Lawler 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Harriss 1988, p. 123.

- ^ Jacob 1993, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Harriss 2004a.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 76.

- ^ Beltz 1841, p. 419.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 40.

- ^ Jones 1983, p. 76.

- ^ Jones 1983, p. 80.

- ^ de Lisle 2014, p. 469 n.26.

- ^ a b Jones 1983, p. 285.

- ^ Curry 2003, p. 154.

- ^ McFarlane 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Harding 2002, p. xiv.

- ^ Allmand 1983, p. 71.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Castor 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Gundy 2002, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Carpenter 1997, p. 109.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 66.

- ^ a b Castor 2000, p. 254.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c Rawcliffe 1978, p. 67.

- ^ Reeves 1972, p. 80.

- ^ Hicks 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Bernard 1992, p. 83.

- ^ McFarlane 1980, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d Pugh 1972, p. 105.

- ^ Britnell 1995, p. 55.

- ^ McFarlane 1980, p. 223.

- ^ Britnell 1995, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Harris 1986, p. 15.

- ^ Hicks 2013, pp. 104–109.

- ^ Crouch & Carpenter 1991, p. 178.

- ^ McFarlane 1981, p. 29.

- ^ Hicks 2013, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 68.

- ^ Harriss 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Lustig 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 142.

- ^ Castor 2000, p. 264.

- ^ Baugh 1933, p. 4.

- ^ Hicks 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Ross 1986, p. 165.

- ^ Baugh 1933, p. 6.

- ^ Castor 2000, pp. 261–263.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 643.

- ^ Carpenter 1997, p. 126.

- ^ Castor 2000, p. 277.

- ^ a b Grummitt 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Jones 1983, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Grummitt 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Harris 1986, p. 14.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, pp. 470–471.

- ^ Grummitt 2008, p. 68.

- ^ Grummitt 2008, p. 98.

- ^ a b Grummitt 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 343.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 281.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 21.

- ^ a b Harriss 2006, p. 614.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 11.

- ^ McFarlane 1980, p. 153.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 358.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 527.

- ^ McFarlane 1981, p. 234.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, pp. 610–611.

- ^ a b Harris 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 641.

- ^ a b Griffiths 1981, p. 648.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 24.

- ^ Carpenter 1997, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Hicks 2014, p. 86.

- ^ a b Griffiths 1981, p. 721.

- ^ Storey 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Gillingham 2001, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 716.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 723.

- ^ a b Johnson 1991, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Rawcliffe 1978, p. 25.

- ^ Lander 1981, p. 194.

- ^ Hicks 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Bean 1989, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Goodman 1990, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong 1960, p. 24.

- ^ a b Armstrong 1960, p. 23.

- ^ Carpenter 1997, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Grummitt 2014, p. 45.

- ^ a b Hicks 2014, p. 110.

- ^ Harriss 2006, p. 632.

- ^ a b Armstrong 1960, p. 31.

- ^ Lander 1981, p. 195.

- ^ a b c Goodman 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Armstrong 1960, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Goodman 1990, p. 25.

- ^ Armstrong 1960, p. 5.

- ^ Gillingham 2001, p. 88.

- ^ a b Armstrong 1960, p. 41.

- ^ a b Hicks 2002, p. 116.

- ^ a b Armstrong 1960, p. 46.

- ^ a b Grummitt 2015, p. 179.

- ^ Armstrong 1960, p. 42 n.3.

- ^ Gillingham 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Armstrong 1960, pp. 69–70 n.5.

- ^ Harris 1986, p. 19.

- ^ McFarlane 1981, p. 235.

- ^ Armstrong 1960, p. 56.

- ^ Hicks 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Grummitt 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Lander 1981, p. 218.

- ^ Pollard 1995, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Pugh 1972, p. 106.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Ross 1986, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d Rawcliffe 1978, p. 27.

- ^ a b Rawcliffe 1978, p. 26.

- ^ Gillingham 2001, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman 1990, p. 37.

- ^ a b Hicks 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Gillingham 2001, p. 124.

- ^ a b Lewis 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Ross 1986, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman 1990, p. 38.

- ^ Harriss 2006, p. 642.

- ^ Harris 2002, p. 154.

- ^ a b Lustig 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Lustig 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Griffiths 1981, p. 135.

- ^ a b Gertsman & Stevenson 2012, p. 105.

- ^ McFarlane 1981, p. 218.

- ^ Harris 1986, p. 1.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 121.

- ^ Harris 1986, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Rawcliffe 1978, p. 19.

- ^ a b Hicks 2014, p. 154.

- ^ Ross 1972, p. 55.

- ^ Davies 2004.

- ^ Charlton 2002, p. 185.

- ^ The Greyfriars Research Team, Kennedy & Foxhall 2015, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Tait 1898, p. 453.

- ^ Kleinschmidt 2000, p. 296.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 112.

- ^ Dunham 1907, p. xviii.

- ^ a b c Tait 1898, pp. 452–453.

- ^ Logan 1979, p. 93.

- ^ Zimbalist 2012, p. 132 n.2.

- ^ Harriss 2004b.

- ^ Ross 1952.

- ^ a b McFarlane 1980, p. 206.

- ^ Harris 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Biancalana 2001, p. 436.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 735.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1978, p. 23.

- ^ Griffiths 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Cokayne 1913, p. 355.

- ^ McFarlane 1980, p. 87.

- ^ Nicolas 1826, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Dobson, Wells & Sullivan 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Wiggins & Richardson 2015, p. 203.

Bibliography

- Allmand, C. T. (1983). Lancastrian Normandy, 1415–1450: The History of Medieval Occupation. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19822-642-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allmand, C. T. (2014). Henry V. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30021-293-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Armstrong, C. A. J. (1960). "Politics and the Battle of St. Albans, 1455". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. 33: 1–72. OCLC 1001092266.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baugh, A. C. (1933). "Documenting Sir Thomas Malory". Speculum. 8: 3–29. OCLC 504113521.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bean, J. M. W. (1989). From Lord to Patron: Lordship in Late Medieval England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71902-855-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beltz, G. F. (1841). Memorials of the Order of the Garter, from Its Foundation to the Present Time. London: W. Pickering. OCLC 4706731.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernard, G. W. (1992). The Tudor Nobility. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71903-625-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Biancalana, J. (2001). The Fee Tail and the Common Recovery in Medieval England: 1176–1502. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13943-082-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Britnell, R. H. (1995). "The Economic Context". In Pollard, A. J. (ed.). The Wars of the Roses. London: St. Martin's Press. pp. 41–64. ISBN 978-0-31212-699-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carpenter, C. (1997). The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, c.1437–1509. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52131-874-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Castor, H. (2000). The King, the Crown, and the Duchy of Lancaster: Public Authority and Private Power, 1399–1461. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19154-248-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Charlton, K. (2002). Women, Religion and Education in Early Modern England. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13467-659-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cokayne, G. E. (1912). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant. Vol. 2. London: St Catherine Press. OCLC 926878974.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cokayne, G. E. (1913). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant. Vol. 3. London: St Catherine Press. OCLC 312790481.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cokayne, G. E. (1959). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant. Vol. 12. London: St Catherine Press. OCLC 312826326.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crouch, D.; Carpenter, D. A. (1991). "Bastard feudalism Revised". Past & Present. 131: 165–189. OCLC 664602455.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curry, A. (2003). The Hundred Years War. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23062-969-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, C. (2004). "Stafford, Henry, Second Duke of Buckingham (1455–1483), Magnate and Rebel". OxfordDictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001 (inactive 15 January 2019). Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2019 (link) - Dobson, M.; Wells, S.; Sullivan, E. (2015). The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19870-873-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunham, I. W. (1907). Dunham Genealogy: English and American Branches of the Dunham Family. Norwich, CT: Bulletin Print. OCLC 10378604.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gertsman, E.; Stevenson, J. (2012). Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-697-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillingham, J. (2001). The Wars of the Roses: Peace and Conflict in 15th Century England. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-274-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goodman, A. (1990). The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–1497. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-41505-264-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffiths, R. A. (1979). "The Sense of Dynasty in the Reign of Henry VI". In Ross, C. D. (ed.). Patronage, Pedigree, and Power in Later Medieval England. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 13–31. ISBN 978-0-84766-205-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffiths, R. A. (1981). The Reign of King Henry VI: The Exercise of Royal Authority, 1422–1461. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52004-372-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grummitt, D. (2008). The Calais Garrison: War and Military Service in England, 1436–1558. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84383-398-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grummitt, D. (2014). A Short History of the Wars of the Roses. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-303-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grummitt, D. (2015). Henry VI. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31748-260-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gundy, A. K. (2002). "The Earl of Warwick and the Royal Affinity in the Politics of the West Midlands, 1389-99". In Hicks, M. A. (ed.). Revolution and Consumption in Later Medieval England. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 57–70. ISBN 978-0-85115-832-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harding, V. (2002). The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500-1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52181-126-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, B. J. (1986). Edward Stafford, Third Duke of Buckingham, 1478–1521. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80471-316-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, B. J. (2002). English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19515-128-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, P. (2006). Income Tax in Common Law Jurisdictions: From the Origins to 1820. Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-51149-548-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harriss, G. L. (1988). Cardinal Beaufort: A Study of Lancastrian Ascendancy and Decline. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19820-135-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harriss, G. L. (2004a). "Beaufort, Henry (1375?–1447)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001 (inactive 15 January 2019). Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2019 (link) - Harriss, G. L. (2004b). "Beaufort, John, marquess of Dorset and marquess of Somerset (c. 1371–1410)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001 (inactive 15 January 2019). Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2019 (link) - Harriss, G. L. (2006). Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19921-119-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hicks, M. A. (2002). Warwick the Kingmaker. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-47075-193-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hicks, M. A. (2013). Bastard Feudalism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31789-896-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hicks, M. A. (2014). The Wars of the Roses: 1455–1485. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47281-018-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jacob, E. F. (1993). The Fifteenth Century, 1399–1485. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19285-286-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, P. A. (1991). Duke Richard of York 1411–1460. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19820-268-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, M. K. (1983). The Beaufort Family and the War in France 1421–1450 (Doctoral thesis). University of Bristol.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kenny, G. (2003). "The Power of Dower: The Importance of Dower in the Lives of Medieval Women in Ireland". In Meek, C.; Lawless, C. (eds.). Studies on Medieval and Early Modern Women: Pawns Or Players?. Dublin: Four Courts. pp. 59–74. ISBN 978-1-85182-775-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kleinschmidt, H. (2000). Understanding the Middle Ages: The Transformation of Ideas and Attitudes in the Medieval World. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-770-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lander, J. R. (1981). Government and Community: England, 1450–1509. New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67435-794-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lawler, J. J.; Lawler, G. G. (2000) [1940]. A Short Historical Introduction to the Law of Real Property (repr. ed.). Washington: Beard Books. ISBN 978-1-58798-032-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, M. (2015). The Wars of the Roses: The Key Players in the Struggle for Supremacy. Gloucester: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-44564-636-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - de Lisle, L. (2014). Tudor: The Family Story. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09955-528-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Logan, H. M. (1979). "KLIC: A Computer Aid to Graphological Analysis". In Gilmour-Bryson A. (ed.). Medieval Studies and the Computer: Computers and The Humanities. New York, NY: Elsevier Science. p. 93–96. ISBN 978-1-48313-636-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lustig, T. L. (2014). Knight Prisoner: Thomas Malory Then and Now. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-78284-118-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matusiak, J. (2012). Henry V. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13616-251-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McFarlane, K. B. (1980). The Nobility of Later Medieval England: The Ford Lectures for 1953 and Related Studies. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19822-657-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McFarlane, K. B. (1981). England in the Fifteenth Century: Collected Essays. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-82644-191-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nicolas, N. H. (1826). Testamenta Vetusta. Vol. I. London: Nichols & son. OCLC 78175058.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pollard, A. J. (1995). The Wars of the Roses. London: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-31212-699-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pugh, T. B. (1972). "The Magnates, Knights and Gentry". In Chrimes, S. B.; Ross, C. D.; Griffiths, R. A. (eds.). Fifteenth-century England, 1399–1509: Studies in Politics and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 86–128. ISBN 978-0-06491-126-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rawcliffe, C. (1978). The Staffords, Earls of Stafford and Dukes of Buckingham: 1394–1521. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52121-663-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rawcliffe, C. (2004). "Stafford, Humphrey, first duke of Buckingham (1402–1460)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001 (inactive 15 January 2019). Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.