Edward Carpenter: Difference between revisions

Jakeeveritt (talk | contribs) |

Added Category:Utopian socialists |

||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

[[Category:Social Democratic Federation members]] |

[[Category:Social Democratic Federation members]] |

||

[[Category:Socialist League (UK, 1885) members]] |

[[Category:Socialist League (UK, 1885) members]] |

||

[[Category:Utopian socialists]] |

|||

[[Category:Vegetarianism activists]] |

[[Category:Vegetarianism activists]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century LGBT people]] |

[[Category:20th-century LGBT people]] |

||

Revision as of 02:46, 21 September 2021

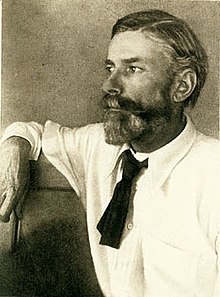

Edward Carpenter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Edward Carpenter 29 August 1844 |

| Died | 28 June 1929 (aged 84) |

| Occupations | |

| Partner | George Merrill (1891–1928) |

| Signature | |

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rights[1] and prison reform whilst advocating vegetarianism and taking a stance against vivisection.[2][3] As a philosopher he was particularly known for his publication of Civilisation: Its Cause and Cure. Here he described civilisation as a form of disease through which human societies pass.[4]

An early advocate of sexual liberation, he had an influence on both D. H. Lawrence[5] and Sri Aurobindo, and inspired E. M. Forster's novel Maurice.[6][7]

Early life

Born at 45 Brunswick Square, Hove in Sussex, Carpenter was educated at nearby Brighton College, where his father was a governor. His brothers Charles, George and Alfred also went to school there. When he was ten, Carpenter displayed a flair for the piano.[8]

His academic ability became evident relatively late in his youth, but was sufficient to earn him a place at Trinity Hall, Cambridge.[9] At Trinity Hall, Carpenter came under the influence of Christian Socialist theologian F. D. Maurice.[10] Whilst there he also began to explore his feelings for men. One of the most notable examples of this is his close friendship with Edward Anthony Beck (later Master of Trinity Hall), which, according to Carpenter, had "a touch of romance".[8] Beck eventually ended their friendship, causing Carpenter great emotional heartache. Carpenter graduated as 10th Wrangler in 1868.[11] After university, he was ordained as curate of the Church of England, "as a convention rather than out of deep Conviction",[12] and served as curate to Maurice at the parish of St Edward's, Cambridge.

In 1871 Carpenter was invited to become tutor to the royal princes George Frederick (later King George V) and his elder brother, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, but declined the position. His lifelong friend and fellow Cambridge student John Neale Dalton took the position.[13] Carpenter continued to visit Dalton while he was tutor. They were given photographs of the pair, taken by the princes.[14]

In the following years he experienced an increasing sense of dissatisfaction with his life in the church and university, and became weary of what he saw as the hypocrisy of Victorian society.[8] He found great solace in reading poetry, later remarking that his discovery of the work of Walt Whitman caused "a profound change" in him.[15] Five or six years later he visited Whitman in Camden, New Jersey, in 1877.

Move to the North of England

Carpenter was voluntarily released from the Anglican ministry and left the church in 1874 and moved to Leeds, becoming a lecturer as part of University Extension Movement, which was formed by academics who wished to widen access to education in deprived communities. He lectured in astronomy, the lives of ancient Greek women and music and had hoped to lecture to the working classes, but found his lectures were mostly attended by middle class people, many of whom showed little active interest in the subjects he taught. Disillusioned,[8] he moved to Chesterfield, but finding that town dull, moved to nearby Sheffield a year later.[9] Here he came into contact with manual workers, and he began to write poetry. His sexual preferences were for working men: "the grimy and oil-besmeared figure of a stoker" or "the thick-thighed hot coarse-fleshed young bricklayer with a strap around his waist".[16]

When his father Charles Carpenter died in 1882, Edward inherited the sum of £6,000 (equivalent to £760,000 in 2023[17]).[18] This enabled Carpenter to quit his lectureship to seek the simpler life, first on a small holding at Totley near Sheffield with Albert Ferneyhough, a scythe-maker, and his family in 1880; Albert and Edward became lovers and in 1883 moved to Millthorpe, Derbyshire together with Albert's family, where Carpenter built a large new house with outbuildings in 1883 constructed of local gritstone with a slate roof, in the style of the seventeenth century.[19] There they had a small market garden and made and sold leather sandals,[20] based on the design of sandals sent to him from India by Harold Cox on Carpenter's request.[20]

Carpenter popularised the phrase the "Simple Life" in his essay Simplification of Life in his England's Ideal (1887).[21] Sheffield architect Raymond Unwin was a frequent visitor to Millthorpe and the simple revival of vernacular English architecture at Millthorpe and Carpenter's 'simple life' there were powerful influences on Unwin's later Garden City architecture and ideals, suggesting as they did a coherent but radical new lifestyle.[20]

In Sheffield, Carpenter became increasingly radical.[20] Influenced by a disciple of Engels, Henry Hyndman, he joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in 1883 and attempted to form a branch in the city. The group instead chose to remain independent, and became the Sheffield Socialist Society.[22] While in the city he worked on a number of projects including highlighting the poor living conditions of industrial workers. In 1884, he left the SDF with William Morris to join the Socialist League. From there he stayed with William Harrison Riley while he was visiting Walt Whitman.[23]

In 1883, Carpenter published the first part of Towards Democracy, a long poem expressing Carpenter's ideas about "spiritual democracy" and how Carpenter believed humanity could move towards a freer and more just society. Towards Democracy was heavily influenced by Whitman's poetry, as well as the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita.[10][24] Expanded editions of Towards Democracy appeared in 1885, 1892, and 1902; the complete edition of Towards Democracy was published in 1905.[24]

In 1886-7 Carpenter was in a tender relationship with George Hukin, a razor grinder.[19] Carpenter lived with Cecil Reddie from 1888 to 1889 and in 1889 helped Reddie found Abbotsholme School in Derbyshire as a notably progressive alternative to the traditional public school, with the financial support of Robert Muirhead and William Cassels.[25]

In May 1889, Carpenter wrote a piece in the Sheffield Independent calling Sheffield the laughing-stock of the civilized world and said that the giant thick cloud of smog rising out of Sheffield was like the smoke arising from Judgment Day, and that it was the altar on which the lives of many thousands would be sacrificed. He said that 100,000 adults and children were struggling to find sunlight and air, enduring miserable lives, unable to breathe and dying of related illnesses.[26]

Travel in India

Drawn increasingly to Hindu philosophy, he travelled to India and Ceylon in 1890. Following conversations with the guru Ramaswamy (known as the Gnani) there, he developed the conviction that socialism would bring about a revolution in human consciousness as well as of economic conditions. His account of the travel was published in 1892 as From Adam's Peak to Elephanta: Sketches in Ceylon and India. The book's spiritual explorations would subsequently influence the Russian author Peter Ouspensky, who discusses it extensively in his own book, Tertium Organum (1912).

Life with George Merrill

On his return from India in 1891, he met George Merrill, a working-class man also from Sheffield, 22 years his junior, and after the Ferneyhoughs left Millthorpe in 1893 Merrill became Carpenter's companion. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives,[19] cohabiting from 1898.[9] Merrill, the son of an engine driver, had been raised in the slums of Sheffield and had little formal education.

Carpenter remarked in his work The Intermediate Sex:

Eros is a great leveller. Perhaps the true Democracy rests, more firmly than anywhere else, on a sentiment which easily passes the bounds of class and caste, and unites in the closest affection the most estranged ranks of society. It is noticeable how often Uranians of good position and breeding are drawn to rougher types, as of manual workers, and frequently very permanent alliances grow up in this way, which although not publicly acknowledged have a decided influence on social institutions, customs and political tendencies.[27]

Carpenter included among his friends the scholar, author, naturalist, and founder of the Humanitarian League, Henry S. Salt, and his wife, Catherine;[28] the critic, essayist and sexologist, Havelock Ellis, and his wife, Edith; actor and producer Ben Iden Payne; Labour activists Bruce and Katharine Glasier; writer and scholar, John Addington Symonds; and the writer and feminist, Olive Schreiner.[29]

E. M. Forster was a close friend and visited the couple regularly. He later recounted that it was a visit to Millthorpe in 1913 that inspired him to write his gay-themed novel, Maurice.[7][30] Forster wrote in his terminal note to the aforementioned novel that Merrill "touched my backside – gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most people's. The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long vanished tooth. He made a profound impression on me and touched a creative spring."[31][7]

The relationship between Carpenter and Merrill was an inspiration for the relationship between Maurice Hall and Alec Scudder, the gamekeeper in Maurice.[31][30] The author D. H. Lawrence read the manuscript of Maurice, which was published posthumously in 1971. Carpenter's rural lifestyle and the manuscript influenced Lawrence's 1928 novel Lady Chatterley's Lover which, though built around a central relationship between a man and a woman, involves a gamekeeper and a member of the upper-class.[32][33]

Later life

In 1902 Carpenter's anthology of verse and prose, Ioläus: An Anthology of Friendship, was published.[34][35][36] The book was published again in 1906 by William Swan Sonnenschein.[37]

In 1915, he published The Healing of Nations and the Hidden Sources of Their Strife, where he argued that the source of war and discontent in western society was class-monopoly and social inequality.

Carpenter became an advocate of the Christ myth theory.[38] His book Pagan and Christian Creeds was published by Harcourt, Brace and Howe in 1921.[39]

The death of George Hukin in 1917 at the age of 56 seems to have broken Carpenter's attachment to the North of England. In 1922 he & Merrill moved to Guildford, Surrey [40] and the two lived at 23 Mountside Rd.[41] On Carpenter's 80th birthday he was presented an album signed by every member of the then Labour Government, headed by Ramsay MacDonald, Prime Minister, who Carpenter had known since his teenage years.[42]

In January 1928, Merrill died suddenly, having become dependent on alcohol since moving to Surrey.[9] Carpenter was devastated and he sold their house and lodged for a short time, with his companion and carer Ted Inigan, at 17 Wodeland Avenue, just a short walk from Mountside. They then moved to a bungalow called 'Inglenook' in Josephs Road.[41] In May 1928, Carpenter suffered a paralytic stroke. He lived another 13 months before he died on 28 June 1929, aged 84.[9] He was interred in the same grave as Merrill at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford under a lengthy invocation written by Carpenter.[20]

His obituary in The Times was headed "Edward Carpenter, Author and Poet",[43] though the text did also refer to his political campaigns.

Influence

Carpenter corresponded with many leading figures in political and cultural circles, among them Annie Besant, Isadora Duncan, Havelock Ellis, Roger Fry, Mahatma Gandhi, Keir Hardie, Jack London, George Merrill, E. D. Morel, William Morris, Edward R. Pease, John Ruskin, and Olive Schreiner.[44]

Carpenter was a friend of Rabindranath Tagore, and of Walt Whitman.[45] Aldous Huxley recommended Carpenter's pamphlet Civilization: Its Cause and Cure in his book Science, Liberty and Peace.[46] Modernist art critic Herbert Read credited Carpenter's pamphlet Non-Governmental Society with converting him to anarchism.[47]

Leslie Paul was influenced by Carpenter's work; in turn he passed on Carpenter's ideas to the scouting group he founded, The Woodcraft Folk.[48] Algernon Blackwood was another devotee of Carpenter's work; Blackwood corresponded with Carpenter and included a quotation from Civilization: Its Cause and Cure in his 1911 novel The Centaur.[49]

Fenner Brockway, in a 1929 obituary of Carpenter, acknowledged him as an influence on Brockway and his associates when young. Brockway described Carpenter as "the greatest spiritual inspiration of our lives. Towards Democracy was our Bible."[50] Ansel Adams was an admirer of Carpenter's writings, especially Towards Democracy.[51] Emma Goldman cited Carpenter's books as an influence on her thought, and stated that Carpenter possessed "the wisdom of the sage."[52] Countee Cullen said about reading Carpenter's book Iolaus that "It opened up for me soul windows which had been closed".[53]

Carpenter was sometimes called "the English Tolstoy" and Tolstoy himself considered him "a worthy heir of Carlyle and Ruskin".[19]

Revival of reputation

Following his death, Carpenter's written works fell out of print and were largely forgotten except among devotees of British labour movement history. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, interest in his work was revived by historians such as Jeffrey Weeks and Sheila Rowbotham, and some of Carpenter's works were reprinted by the Gay Men's Press.[54] Carpenter's opposition to pollution and cruelty to animals have resulted in some historians arguing Carpenter's ideas anticipated the modern Green and animal rights movements.[55][56] Carpenter was described by Fiona MacCarthy as the "Saint in Sandals", the "Noble Savage" and, more recently, the "gay godfather of the British left".[57]

Written works

Chants of Labour was a songbook for socialists, contributions to which Carpenter had solicited in The Commonweal.[58] It comprised works by John Glasse, Edith Nesbit, John Bruce Glasier, Andreas Scheu, William Morris, Jim Connell, Herbert Burrows, and others.[58]

See also

References

- ^ Warren Allen Smith: Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-Theists, Barricade Books, New York, 2000, p. 186; ISBN 978-1-56980-158-1.

- ^ Rowbotham, Sheila (2008). Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love. Verso. p. 310. ISBN 9781844672950.

- ^ O'Neill, Charlotte (7 January 2019). "Edward Carpenter: A Nonhuman Bibliography, by Charlotte O'Neill – Sheffield Animal Studies Research Centre". Sheffield Animal Studies Research Centre. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Carpenter, Edward. Civilisation, Its Cause and Cure.

- ^ Delaveny, Emile (1971) D. H. Lawrence and Edward Carpenter: A Study in Edwardian Transition. New York: Taplinger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0800821807

- ^ Andrew Harvey, ed. (1997). The Essential Gay Mystics.

- ^ a b c Symondson, Kate (25 May 2016) E M Forster’s gay fiction . The British Library website. Retrieved 18 July 2020

- ^ a b c d "Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams, London: Unwin, 1916". Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Rowbotham 2009.

- ^ a b Birch, Dinah, The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780191030840 (p. 197).

- ^ "Carpenter, Edward (CRPR864E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Philip Taylor's Biography of Carpenter Archived 27 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Philip Taylor 1988

- ^ Aronson p.48.

- ^ Aronson p.50.

- ^ Carpenter, My Days and Dreams p. 64.

- ^ Aronson p.49 citing d'Arch Smith, Love in Earnest p. 192

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Rowbotham, Sheila (2008). Edward Carpenter: a life of liberty and love. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-295-0.

- ^ a b c d Tsuzuki, Chushichi (2012) [2004]. "Carpenter, Edward (1844–1929)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32300. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e "Millthorpe and Edward Carpenter". Historic England. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Delany 1987, p. 10.

- ^ "Edward Carpenter: Red, Green and Gay". SocialismToday. September 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ David Goodway, Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow, p.44

- ^ a b Robertson, Michael, Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples Princeton University Press, 2010 ISBN 0691146314 (pp. 179-180)

- ^ "The Edward Carpenter Archive". Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Edward Carpenter, Letter, Sheffield Independent (25 May 1889)

- ^ Edward Carpenter The Intermediate Sex, p.114-115

- ^ George and Willene Hendrick (1989). The Savour of Salt: A Henry Salt Anthology. Centaur Press. p. 153.

- ^ Gray, Stephen. 2013. Two Dissident Dream-Walkers: The Hardly Explored Reformist Alliance between Olive Schreiner and Edward Carpenter. English Academy Review: Southern African Journal of English Studies Volume 30, Issue 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Rowse, A. L. (1977). Homosexuals in History: A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature, and the Arts. New York, New York: Macmillan. pp. 282–283. ISBN 0-88029-011-0.

- ^ a b Sutherland, John; Fender, Stephen (2011) Love, Sex, Death & Words: Surprising Tales From a Year in Literature, p. 160. London: Icon Books. Retrieved 11 August 2020 (Google Books)

- ^ Smith, Helen (5 October 2015). Masculinity, Class and Same-Sex Desire in Industrial England, 1895-1957. Springer. ISBN 9781137470997 – via Google Books.

- ^ King, Dixie (1982) "The Influence of Forster's Maurice on Lady Chatterley's Lover" in Contemporary Literature Vol. 23, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 65-82

- ^ The 1917 New York edition is now available as a free e-book

- ^ "People with a History: An Online Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans* History". fordham.edu. 1997. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Carpenter, Edward; Corey, D. Steven (24 March 2018). "Ioläus : an anthology of friendship". London : Swan Sonnenschein ; Manchester: the author ; Boston : Goodspeed. Retrieved 24 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Carpenter, Edward (10 September 2017). Ioläus: an anthology of friendship. Swan Sonnenschein.

- ^ Larson, Martin Alfred. (1977). The Story of Christian Origins: Or, The Sources and Establishment of Western Religion. J. J. Binns. p. 304

- ^ Pagan & Christian creeds: Their origin and meaning. Harcourt, Brace and Howe. 1921.

- ^ Brighton Ourstory Project - Lesbian and Gay History Group at www.brightonourstory.co.uk

- ^ a b "Edward Carpenter (1844 – 1929)". exploringsurreyspast.org.uk. 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ The Times, 'Edward Carpenter,Democratic Author and Poet', June 29, 1929 p.14

- ^ The Times, Saturday June 29th, 1929 p.14.

- ^ "Fabian Economic and Social Thought Series One: The Papers of Edward Carpenter, 1844-1929", from Sheffield Archives Part 1: Correspondence and Manuscripts Archived 6 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine at www.adam-matthew-publications.co.uk

- ^ Excerpt from Gay Roots Vol. 1: THE GAY SUCCESSION The following document first appeared in Gay Sunshine Journal 35 (1978) and was reprinted as an appendix to the Allen Ginsberg interview in the book Gay Sunshine Interviews, Volume 1, Gay Sunshine Press, 1978. retrieved 16 September 2014

- ^ Rowbotham, 2008. (p. 449)

- ^ Goodway, David, "The Politics of Herbert Read", in Goodway (ed.), Herbert Read reassessed Liverpool : Liverpool University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780853238720 (p.177).

- ^ Wall, Derek, Green History : A Reader in Environmental Literature, Philosophy and Politics, London, Routledge, 1993. ISBN 041507925X (pp. 232-34)

- ^ Ashley, Michael, Algernon Blackwood : An Extraordinary Life. New York : Carroll & Graf, 2001. ISBN 9780786709281 (p. 172-173)

- ^ Fenner Brockway, "A Memory of Edward Carpenter", New Leader, 5 July 1929, (p.6). Quoted in Harris, Kirsten, Walt Whitman and British socialism: The Love of Comrades. Basingstoke : Taylor & Francis Ltd 2016. ISBN 9781138796270 (p.60)

- ^ Spaulding, Jonathan,Ansel Adams and the American Landscape: A Biography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 9780520216631 (p.49)

- ^ Haaland, Bonnie, Emma Goldman : sexuality and the impurity of the state. Montréal : Black Rose Books, 1993.ISBN 9781895431643 (p. 138)

- ^ Schwarz, A. B. Christa, Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press, 2003 (p.50)

- ^ "Edward Carpenter's role in rethinking sexual embodiment and theorizing homosexuality – or 'Uranism' as he termed it – has received welcome attention in the past few decades. The republication of his works by the Gay Men's Press and enlightening studies by the likes of Sheila Rowbotham and Jeffrey Weeks in the late 1970s and early 1980s coincided with the decline of Marxist orthodoxy as attention shifted to alternative radical histories- of gender and sexuality - within the academy and beyond." Livesey, Ruth, Socialism, Sex, and the Culture of Aestheticism in Britain, 1880-1914. Oxford University Press, 2009.ISBN 0197263984. (p. 112)

- ^ "Another prominent early green political activist was Edward Carpenter, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An openly gay man, an advocated of feminism and animal rights...he believed the "vast majority of mankind [sic] must live in direct contact with nature."" Wall, Derek, The No-Nonsense Guide to Green Politics. Oxford : New Internationalist, 2014. ISBN 9781906523398, (p.18).

- ^ "...Edward Carpenter, the Cambridge cleric who moved to the country for a simple life and became a key figure in a number of reform movements.Carpenter was a socialist, environmentalist and an advocate of prisons reform." (p.18) Clum, John M. The drama of marriage : gay playwrights/straight unions from Oscar Wilde to the present.Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. ISBN 9780230338401 (p.18)

- ^ MacCarthy, Fiona (November 2008). "Review: Edward Carpenter by Eliot Smith - Books - The Guardian". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Bowan 2017, p. 92.

Bibliography

- Aronson, Theo (1994). Prince Eddy and the Homosexual Underworld. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5278 8.

- Beith, Gilbert (ed), Edward Carpenter: In Appreciation, George Allen & Unwin, 1931.

- Bowan, Kate (2017). "Friendship, cosmopolitan connections, and Late Victorian Socialist songbook culture". In Watt, Paul; Scott, Derek B.; Spedding, Patrick (eds.). Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107159914.

- Brown, Tony, ed. (1990). Edward Carpenter and Late Victorian Radicalism. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-71463-400-5.

- Delany, Paul (1987). The Neo-pagans: Rupert Brooke and the ordeal of youth. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-908280-5.

- Greig, Noël: Dear Love of Comrades: London: Gay Men's Press, 1979.

- Lewis, Edward, Edward Carpenter: An Exposition and an Appreciation, Macmillan, 1915.

- Stanley Pierson, "Edward Carpenter, Prophet of a Socialist Millennium," Victorian Studies, vol. 13, no. 3 (March 1970), pp. 301–318.

- Rowbotham, Sheila (1980). "In search of Edward Carpenter". Radical America. 14 (4): 48–59.

- Rowbotham, Sheila (2009). Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love. London: Verso. ISBN 9781844674213.

- Toibin, Colm (29 January 2009). "Urning". London Review of Books. No. 29 January 2009. LRB. pp. 14–16.

- Tsuzuki, Chushchi, Edward Carpenter 1844-1929 Prophet of Human Fellowship, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Twigg, Julia The Vegetarian Movement in England 1847-1981, PhD (LSE) thesis, 1981, in particular Chapter Six e, i, as on the International Vegetarian Union website.

External links

![]() Media related to Edward Carpenter at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edward Carpenter at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by Edward Carpenter at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Edward Carpenter at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sheffield Archives. Edward Carpenter Collection

- Edward Carpenter Archive at marxists.org

- Millthorpe and Edward Carpenter, Historic England

- 1844 births

- 1929 deaths

- 19th-century LGBT people

- Animal rights activists

- Anti-vivisectionists

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- Anglican socialists

- Christ myth theory proponents

- English Christian socialists

- English male poets

- English pacifists

- Free love advocates

- Gay writers

- LGBT Anglicans

- LGBT rights activists from England

- Libertarian socialists

- Members of the Fabian Society

- People educated at Brighton College

- People from Hove

- People from North East Derbyshire District

- Social Democratic Federation members

- Socialist League (UK, 1885) members

- Utopian socialists

- Vegetarianism activists

- 20th-century LGBT people