Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany: Difference between revisions

Selfstudier (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1102176475 by EricSpokane (talk) A senior project is no use, minimum WP level is a PHD |

there are multiple sources for that Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

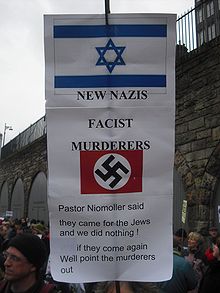

[[File:Protests Edinburgh 10 1 2009 5.JPG|thumb|This poster shown within a 2009 demonstration inside the Scottish city of [[Edinburgh]] points at Israel as a nation of "fascist murderers".]] |

[[File:Protests Edinburgh 10 1 2009 5.JPG|thumb|This poster shown within a 2009 demonstration inside the Scottish city of [[Edinburgh]] points at Israel as a nation of "fascist murderers".]] |

||

'''Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany''' have been made since the [[1940s]], taking place first within the larger context of the [[aftermath of World War II]]. Such comparisons are a rhetorical staple of [[anti-Zionism]] in relation to the [[Israeli–Palestinian conflict]].<ref name="Klaff">{{cite news|title=Holocaust Inversion and contemporary antisemitism|url=https://fathomjournal.org/holocaust-inversion-and-contemporary-antisemitism/|accessdate=4 May 2022|work=Fathom|first=Lesley|last=Klaff}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Gerstenfeld|first=Manfred|date=2008-01-28|title=Holocaust Inversion|language=en-US|work=Wall Street Journal|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB120147388696520647|access-date=2021-06-11|issn=0099-9660}}</ref> Whether comparisons between [[Israel]] and [[Nazi Germany]] are intrinsically [[antisemitic]] is disputed.{{sfn|Rosenfeld|2019|p=175-178, 186}} |

'''Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany''', also referred to as '''Holocaust inversion''',<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zehnder |first=Lauren |date=2017 |title=Intersectionality : Holocaust Inversion, Omar Barghouti, and Campus Antisemitism |url=https://cache.kzoo.edu/handle/10920/37303 |journal=Political Science Senior Integrated Projects}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=January 25, 2022 |title=Antisemitism defined: Why drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to the Nazis is antisemitic |url=https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/news/antisemitism-defined-why-drawing-comparisons-of-contemporary-israeli-policy-to-the-nazis-is-antisemitic}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Klaff |first=Lesley |date=Winter 2014 |title=Holocaust Inversion and contemporary antisemitism |url=https://fathomjournal.org/holocaust-inversion-and-contemporary-antisemitism/ |journal=Fathom Journal}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Fruchter |first=Noam |date=April 25, 2022 |title=Holocaust Inversion: Unmasking the False Comparisons of Palestinians to the Holocaust |work=The Algemeiner Journal |url=https://www.algemeiner.com/2022/04/25/holocaust-inversion-unmasking-the-false-comparisons-of-palestinians-to-the-holocaust/}}</ref> have been made since the [[1940s]], taking place first within the larger context of the [[aftermath of World War II]]. Such comparisons are a rhetorical staple of [[anti-Zionism]] in relation to the [[Israeli–Palestinian conflict]].<ref name="Klaff">{{cite news|title=Holocaust Inversion and contemporary antisemitism|url=https://fathomjournal.org/holocaust-inversion-and-contemporary-antisemitism/|accessdate=4 May 2022|work=Fathom|first=Lesley|last=Klaff}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Gerstenfeld|first=Manfred|date=2008-01-28|title=Holocaust Inversion|language=en-US|work=Wall Street Journal|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB120147388696520647|access-date=2021-06-11|issn=0099-9660}}</ref> Whether comparisons between [[Israel]] and [[Nazi Germany]] are intrinsically [[antisemitic]] is disputed.{{sfn|Rosenfeld|2019|p=175-178, 186}} |

||

Scholarly analysis has taken place in the broader context of the frequent comparisons made in international [[popular culture]] comparing widely various entities to the historical [[Nazis]]. British academic [[David Feldman (historian)|David Feldman]], director of the [[Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism]], commented that comparisons frequently do not become antisemitic because they take place in the context of a commonly deployed [[rhetorical]] device "used in many arguments about many subjects, often light-mindedly, lacking any specifically antisemitic content", as vastly different entities get compared to the Nazis.{{sfn|Rosenfeld|2019|p=175-178, 186}} The [[Anti-Defamation League]] argued in a statement that antisemitism takes place through what it sees as measures "purposefully directed at Jews in an effort to associate the victims of Nazi crimes with the Nazi perpetrators ... [which] serves to diminish the significance and uniqueness of the Holocaust."<ref name="ADL"/> |

Scholarly analysis has taken place in the broader context of the frequent comparisons made in international [[popular culture]] comparing widely various entities to the historical [[Nazis]]. British academic [[David Feldman (historian)|David Feldman]], director of the [[Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism]], commented that comparisons frequently do not become antisemitic because they take place in the context of a commonly deployed [[rhetorical]] device "used in many arguments about many subjects, often light-mindedly, lacking any specifically antisemitic content", as vastly different entities get compared to the Nazis.{{sfn|Rosenfeld|2019|p=175-178, 186}} The [[Anti-Defamation League]] argued in a statement that antisemitism takes place through what it sees as measures "purposefully directed at Jews in an effort to associate the victims of Nazi crimes with the Nazi perpetrators ... [which] serves to diminish the significance and uniqueness of the Holocaust."<ref name="ADL"/> |

||

Revision as of 01:24, 4 August 2022

Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany, also referred to as Holocaust inversion,[1][2][3][4] have been made since the 1940s, taking place first within the larger context of the aftermath of World War II. Such comparisons are a rhetorical staple of anti-Zionism in relation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[5][6] Whether comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany are intrinsically antisemitic is disputed.[7]

Scholarly analysis has taken place in the broader context of the frequent comparisons made in international popular culture comparing widely various entities to the historical Nazis. British academic David Feldman, director of the Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, commented that comparisons frequently do not become antisemitic because they take place in the context of a commonly deployed rhetorical device "used in many arguments about many subjects, often light-mindedly, lacking any specifically antisemitic content", as vastly different entities get compared to the Nazis.[7] The Anti-Defamation League argued in a statement that antisemitism takes place through what it sees as measures "purposefully directed at Jews in an effort to associate the victims of Nazi crimes with the Nazi perpetrators ... [which] serves to diminish the significance and uniqueness of the Holocaust."[8]

According to political scientist Ian S. Lustick, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, such comparisons are "a natural if unintended consequence of the immersion of Israeli Jews in Holocaust imagery".[9] A wide variety of political figures and governments have made the comparison historically, an example being the administration of the Soviet Union in the context of the Six-Day War within 1960s era Cold War divisions.[10] Politicians in the 21st century who have done so include the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,[11] and British parliamentarian David Ward.[5]

Historical examples

An early example of comparison between Israel and Nazi Germany was a 1948 open letter to the U.S. publication New York Times describing the Herut party as "closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties." The letter was signed by researchers Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt.[12]

Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz introduced the term "Judeo-Nazis." He argued that continued military occupation of the Palestinian territories would lead to the moral degradation of Israeli Defense Force (IDF), with individuals committing atrocities for state security interests.[13][14] In 1988, Holocaust survivor Yehuda Elkana warned that the tendency in Israel to see all potential threats as existential and all opponents as Nazis would lead to Nazi-like behavior by Jews.[15] During the First Intifada, historian Omer Bartov was enraged by Yitzhak Rabin's call to "break the bones" of Palestinians and wrote him a letter arguing that, based on Bartov's research, the IDF could be similarly brutalized as the German Army was during World War II.[16] One Israeli nationalist told Amos Oz that he did not care if Israel was called a Judeo-Nazi state, it was "better [to be] a living Judeo-Nazi than a dead saint."[17] In 2018, Noam Chomsky cited Leibowitz, arguing that he was right in his prediction that the occupation was producing Judeo-Nazis.[18]

According to political scientist Ian S. Lustick, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, such comparisons are "a natural if unintended consequence of the immersion of Israeli Jews in Holocaust imagery", and the term "Holocaust inversion" for Nazi comparisons is used by those who see the Holocaust as a template for Jewish life.[9]

In the context of the Six-Day War, the Soviet Union compared Israeli tactics to those of Nazi Germany during the Second World War in official commentary.[10] After the victory of Likud in the 1977 Israeli legislative election, Holocaust metaphors began to be used by the Israeli right-wing to describe their left-wing opponents.[19] During the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, some settlers donned yellow stars to compare themselves to Holocaust victims, protesting the government's measures.[14] In 2016, Yair Golan, the Israeli general and deputy chief of staff of the IDF, sparked a controversy during a speech at Yom HaShoah. Golan stated: "If there is something that frightens me about the memory of the Holocaust, it is seeing the abhorrent processes that took place in Europe, and Germany in particular, some 70, 80 or 90 years ago, and finding manifestations of these processes here among us in 2016."[20] These remarks were condemned by the prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.[20]

Debate on whether comparisons are antisemitic

The subject of comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany and whether or not such comparisons are antisemitic has received much commentary by academics worldwide who have studied history and politics,[21] including those who have deemed it to be a form of Holocaust trivialization called "Holocaust inversion" due to the potential implication it minimizes the scope of Nazi crimes.[22]

According to Kenneth L. Marcus, the aim of those who employ Holocaust inversion is to "shock, silence, threaten, insulate, and legitimize. ... No one tells Holocaust survivors – or a nation of Holocaust survivors and their children – that they are Nazis without expecting to shock." Even when it is frequently used, the use of Holocaust inversion is still shocking, which facilitates its repeated use. He asserts that the tying together of Nazi motifs with Jewish conspiracy stereotypes has a chilling effect on Jewish supporters of Israel. He also says that by implying guilt, this discourse is threatening because it implies a required punishment. As this discourse is performed in the context of political criticism of Israel, it insulates those who use it from the resistance that most forms of racism face in post-World War II society. Finally, he states that inversion not only legitimizes anti-Israel activities but also legitimizes anti-Jewish activities that would otherwise be hard to conduct.

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (July 2022) |

According to Bernard-Henri Lévy, this erodes societal safeguards allowing "people to feel once again the desire and, above all, the right to burn all the synagogues they want, to attack boys wearing yarmulkes, to harass large number of rabbis... in order for anti-Semitism to be reborn on a large scale."[23]

According to historian Bernard Lewis, the belief that the Nazis were no worse than Israel is has "brought welcome relief to many who had long borne a burden of guilt for the role which they, their families, their nations, or their churches had played in Hitler's crimes against the Jews, whether by participation or complicity, acquiescence or indifference."[22] In Austria, while overt antisemitism has been limited following the Holocaust, the Freedom Party of Austria is associated with using comparisons between Nazi Germany and Israel to delegitimize political opponents.[24]

According to Lustick, many Israelis are "already repelled by actions against Palestinians they cannot help but associate with Nazi persecution of Jews."[20] British scholar David Feldman argued that comparisons in relation to the 2014 Gaza War have not been motivated by a broader anti-Jewish subjectivity but by targeted criticism of Israeli policy in military actions.[7]

The Working Definition of Antisemitism, which was adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the U.S. Department of State, and other organizations, has offered several examples in which criticism of Israel may be antisemitic, including "drawing comparison of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis."[25] This definition is controversial because of concerns that it could be seen as defining legitimate criticisms of Israel as antisemitic and has been used to censor pro-Palestinian activism. Alternative definitions such as the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism have been proposed.[12]

In an official statement, the Anti-Defamation League, an American social activist organization involved with the U.S. Jewish community, has declared that "[a]bsolutely no comparison can be made between the complex Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the atrocities committed by the Nazis against the Jews" given that "[w]hile one can criticize Israel's treatment of the Palestinians, in contrast to the Holocaust, there is not now, nor has there been, a significant Israeli ideology, movement, policy or plan to exterminate the Palestinian population." The statement also labeled comparisons inherently antisemitic.[8]

21st-century discussions and commentary

In the United Kingdom, the-then Member of Parliament for Bradford East, Liberal Democrats politician David Ward, created controversy after signing the ceremonial Book of Remembrance in the Houses of Parliament on Holocaust Memorial Day, with him writing: "I am saddened that the Jews, who suffered unbelievable levels of persecution during the Holocaust, could within a few years of liberation from the death camps be inflicting atrocities on Palestinians in the new state of Israel and continue to do so on a daily basis in the West Bank and Gaza." He later responded to criticism of his statement by alleging that "a huge operation out there" had distorted what he meant.[5] As a result of the scrutiny over the January 2013 controversy, the Liberal Democrats' leadership threatened Ward with formal disciplinary action over his arguments.[26]

In July 2018, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, asserted publicly in Ankara that the "spirit of Hitler" lives on in Israel, commenting specifically that he believes "no difference [exists] between Hitler's obsession with a pure race and the understanding that these ancient lands are just for the Jews." He additionally called the nation-state both "fascist" and "racist". In response, the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, condemned the statements and remarked that he viewed Turkey's government as a "dark dictatorship".[11]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Zehnder, Lauren (2017). "Intersectionality : Holocaust Inversion, Omar Barghouti, and Campus Antisemitism". Political Science Senior Integrated Projects.

- ^ "Antisemitism defined: Why drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to the Nazis is antisemitic". January 25, 2022.

- ^ Klaff, Lesley (Winter 2014). "Holocaust Inversion and contemporary antisemitism". Fathom Journal.

- ^ Fruchter, Noam (April 25, 2022). "Holocaust Inversion: Unmasking the False Comparisons of Palestinians to the Holocaust". The Algemeiner Journal.

- ^ a b c Klaff, Lesley. "Holocaust Inversion and contemporary antisemitism". Fathom. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Gerstenfeld, Manfred (2008-01-28). "Holocaust Inversion". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ a b c Rosenfeld 2019, p. 175-178, 186.

- ^ a b "Allegation: Israel's Actions Against the Palestinians Can be Compared to the Nazis". ADL.org. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b Lustick 2019, p. 52.

- ^ a b Druks, Herbert (2001). The Uncertain Alliance: The U.S. and Israel from Kennedy to the Peace Process. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780313314247.

- ^ a b c "Turkish president calls Israel fascist and racist over nation state law". ITV.com. 24 July 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b Neve Gordon and Mark LeVine (March 26, 2021). "The problems with an increasingly dominant definition of anti-Semitism (opinion)". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Feldhay, Rivka (2013). "The Fragile Boundary between the Political and the Academic". Israel Studies Review. 28 (1): 1–7. doi:10.3167/isr.2013.280102.

- ^ a b Elkad-Lehman, Ilana (2020). "'Judeo-Nazis? Don't talk like this in my house' voicing traumas in a graphic novel – an intertextual analysis". Israel Affairs. 26 (1): 59–79. doi:10.1080/13537121.2020.1697072. S2CID 212958444.

- ^ Bartov 2018, p. 192.

- ^ Bartov 2018, p. 191.

- ^ Oz, Amos (1983). ""Better a Living Judeo-Nazi Than a Dead Saint"". Journal of Palestine Studies. 12 (3): 202–209. doi:10.2307/2536162. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 2536162.

- ^ "i24NEWS". i24news. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Steir-Livny 2019, p. 284.

- ^ a b c Lustick 2019, p. 143.

- ^ Rosenfeld 2019, p. 175–178, 186.

- ^ a b Jewish Identity and Civil Rights in America, Cambridge University Press, Kenneth L. Marcus, page 56

- ^ Jewish Identity and Civil Rights in America, Cambridge University Press, Kenneth L. Marcus, pages 63–64

- ^ Stoegner, Karin (2016). "'We are the new Jews!' and 'The Jewish Lobby'–antisemitism and the construction of a national identity by the Austrian Freedom Party". Nations and Nationalism 22 (3): 484–504.

- ^ Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: The Dynamics of Delegitimization, chapter by Alan Johnson, page 177

- ^ "Lib-Dem David Ward MP censured over Israel criticism". BBC News. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

Bibliography

- Bartov, Omer (2018). "National Narratives of Suffering and Victimhood: Methods and Ethics of Telling the Past as Personal Political History". The Holocaust and the Nakba. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54448-1.

- Lustick, Ian S. (2019). Paradigm Lost: From Two-State Solution to One-State Reality. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-5195-1.

- Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (9 January 2019). Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: The Dynamics of Delegitimization. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-03872-2.

- Marcus, Kenneth L. (30 August 2010). Jewish Identity and Civil Rights in America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49119-8.

- Steir-Livny, Liat (2019). "'Kristallnacht in Tel Aviv': Nazi Associations in the Contemporary Israeli Socio-Political Debate". New Perspectives on Kristallnacht: After 80 Years, the Nazi Pogrom in Global Comparison. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-61249-616-0.

External links

- "Former Pink Floyd frontman sparks fury by comparing Israelis to Nazis" by Vanessa Thorpe and Edward Helmore at The Guardian

- "Israel's 'nation-state law' parallels the Nazi Nuremberg Laws" by Susan Abulhawa at Al Jazeera

- "The Rights and Wrongs of Comparing Israel to Nazi Germany" by Daniel Blatman at Haaretz