Lahaina, Hawaii: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 191.84.237.100 (talk) (HG) (3.4.12) |

→Pre-Western contact: Corrected heading Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

In [[ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi]] (Hawaiian language) the name {{lang|haw|Lā hainā}} means "cruel or merciless (''hainā'') sun (''lā'')", describing the [[Hawaiian tropical low shrublands|sunny dry climate]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://wehewehe.org/cgi-bin/hdict?a=q&j=pp&l=en&q=Lahaina&d=D48691 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120717190829/http://wehewehe.org/cgi-bin/hdict?a=q&j=pp&l=en&q=Lahaina&d=D48691 |url-status=dead |archive-date=2012-07-17 |title=lookup of Lā-hainā |work=on Place Names of Hawai'i |author=Pukui and Elbert |year=2004 |publisher=Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii |access-date=2009-12-31}}</ref><ref name="Clark" /><ref name="Keola" /> |

In [[ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi]] (Hawaiian language) the name {{lang|haw|Lā hainā}} means "cruel or merciless (''hainā'') sun (''lā'')", describing the [[Hawaiian tropical low shrublands|sunny dry climate]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://wehewehe.org/cgi-bin/hdict?a=q&j=pp&l=en&q=Lahaina&d=D48691 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120717190829/http://wehewehe.org/cgi-bin/hdict?a=q&j=pp&l=en&q=Lahaina&d=D48691 |url-status=dead |archive-date=2012-07-17 |title=lookup of Lā-hainā |work=on Place Names of Hawai'i |author=Pukui and Elbert |year=2004 |publisher=Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii |access-date=2009-12-31}}</ref><ref name="Clark" /><ref name="Keola" /> |

||

=== Pre-contact === |

=== Pre-Western contact === |

||

The name Lele was adopted during the reign of the ''mōʻī'' or ''aliʻi'' nui (supreme ruler) known as [[Kakaalaneo|Kakaʻalaneo]]. He held his court there during the joint rule with his brother, while living on a hill called Kekaʻa. It was this ruler who first planted the breadfruit trees.<ref>{{cite book |last= Beckwith|first= Martha Warren|author-link= |date= 1970|title= Hawaiian Mythology|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=BqElGaH4DiIC&dq=Kakaalaneo+ruled+over+Maui+in+Lele&pg=PA384|location= Hawaii|publisher= University of Hawaiʻi Press|page= 884|isbn= 9780870220623|oclc= 96119}}</ref> |

The name Lele was adopted during the reign of the ''mōʻī'' or ''aliʻi'' nui (supreme ruler) known as [[Kakaalaneo|Kakaʻalaneo]]. He held his court there during the joint rule with his brother, while living on a hill called Kekaʻa. It was this ruler who first planted the breadfruit trees.<ref>{{cite book |last= Beckwith|first= Martha Warren|author-link= |date= 1970|title= Hawaiian Mythology|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=BqElGaH4DiIC&dq=Kakaalaneo+ruled+over+Maui+in+Lele&pg=PA384|location= Hawaii|publisher= University of Hawaiʻi Press|page= 884|isbn= 9780870220623|oclc= 96119}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:39, 13 August 2023

This article may be affected by the following current event: 2023 Hawaii wildfires. Information in this article may change rapidly as the event progresses. Initial news reports may be unreliable. The last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (August 2023) |

Lahaina

Lāhainā | |

|---|---|

Downtown Lahaina lies on the waterfront | |

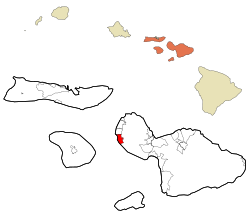

Location in Maui County and the state of Hawaii | |

| Coordinates: 20°52′26″N 156°40′39″W / 20.87389°N 156.67750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Hawaii |

| County | Maui |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.29 sq mi (24.07 km2) |

| • Land | 7.78 sq mi (20.15 km2) |

| • Water | 1.51 sq mi (3.92 km2) |

| Elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 12,702 |

| • Density | 1,632/sq mi (630.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (Hawaii-Aleutian) |

| ZIP Codes | 96761, 96767 |

| Area code | 808 |

| FIPS code | 15-42950 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0361678 |

Lahaina (Hawaiian: Lāhainā) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Maui County, Hawaii, United States, and includes the Kaanapali and Kapalua beach resorts. As of the 2020 census, Lahaina had a resident population of 12,702. The CDP encompasses the coast along Hawaii Route 30 from a tunnel at the south end, through Olowalu and to the CDPs of Kaanapali and Napili-Honokowai to the north.

In August 2023, a wildfire burned down the majority of Lahaina. As of August 13 at least 93 deaths had been confirmed with 1,000+ missing.[2][3]

History

Name

Lahaina's old name was Maluʻuluʻolele, the "breadfruit grove of Lele".[4][5][6] According to legend a bald aliʻi (chief) living in Kauaʻula Valley was walking without a hat and cursed up at the hot sun: He keu hoi keia o ka lā hainā ("What an unmerciful sun").[7][8] In ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) the name Lā hainā means "cruel or merciless (hainā) sun (lā)", describing the sunny dry climate.[9][7][8]

Pre-Western contact

The name Lele was adopted during the reign of the mōʻī or aliʻi nui (supreme ruler) known as Kakaʻalaneo. He held his court there during the joint rule with his brother, while living on a hill called Kekaʻa. It was this ruler who first planted the breadfruit trees.[10]

Western contact, post-contact

Before unification of the islands, the town was conquered by Kamehameha the Great. Lahaina was the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1820 to 1845.[11] King Kamehameha III, son of Kamehameha I, preferred the town to bustling Honolulu. He built a palace complex on a 1 acre (0.40 ha) island Mokuʻula surrounded by a pond called Moku Hina, said to be home to Kiwahine, a spiritual protector of Maui and the Pi'ilani royal line, near the center of town.[12]

In 1824, at the chiefs' request, Betsey Stockton started the first mission school open to the common people.[13] It was once an important destination for the 19th-century whaling fleet, whose presence at Lahaina frequently led to conflicts with the Christian missionaries living there. On more than one occasion the conflict was so severe that it led to sailor riots and even the shelling of Lahaina by the British whaler John Palmer in 1827.

In response, Maui Governor Hoapili built the Old Lahaina Fort in 1831 to protect the town from riotous sailors.[14][15]

In 1845 the capital of Hawaii was moved back to Honolulu. In the 19th century, Lahaina was the center of the global whaling industry, with many sailing ships anchoring at its waterfront; today pleasure craft make their home there. Lahaina's Front Street has been ranked one of the "Top Ten Greatest Streets" by the American Planning Association.[16]

In Lahaina, the focus of activity is along Front Street, which dates back to the 1820s. It is lined with stores and restaurants and often packed with tourists. The Banyan Court Park features an exceptionally large banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis) planted on the site of Kamehameha the Great's first palace by William Owen Smith on April 24, 1873, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of Christian missionaries.[17] The largest banyan tree in the United States, it is 60 ft (18m) tall and has 46 trunks covering an area of 1.94 acres (0.78 hectares).[18]

On January 1, 1919, a major fire destroyed more than thirty buildings in Lahaina before it was extinguished by residents.[19] The 1919 fire led to the creation of the island-wide Maui Fire Department and adoption of new fire safety standards in Lahaina.[19]

It is also the site of the reconstructed ruins of Lahaina Fort, originally built in 1832.[20]

2023 wildfire

In August 2023, much of Lahaina was destroyed by a wildfire amid dry and windy conditions[21] As of August 13 at least 93 people had been confirmed dead with 1,000+ missing.[2][3] At least 11,000 people were forced to evacuate.[22] FEMA estimated that over 2,000 buildings had been destroyed and set the damage estimate at $5.52 billion as of August 11, 2023.[23][24] The mayor of Maui County summarized the situation with this comment: "I'm telling you, none of it's there. It's all burned to the ground."[25] Among the structures destroyed were Waiola Church and Pioneer Inn.[26]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 9.3 square miles (24.1 km2), of which 7.8 square miles (20.2 km2) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.9 km2), or 16.26%, is water.[27]

Climate

Lahaina is one of the driest places in Hawaii because it is in the rain shadow of the West Maui Mountains. There are many different climates in the different districts of Lahaina. The historic district is the driest and calmest and hosts the small boat harbor. Kaanapali is north of a wind line and has double the annual rainfall and frequent breezes. The Kapalua and Napili areas have almost four times the annual rainfall compared to the historic district of Lahaina.

Lahaina has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh) with warm temperatures year-round.

| Climate data for Lahaina, Maui | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

82 (28) |

83 (28) |

84 (29) |

84 (29) |

86 (30) |

87 (31) |

88 (31) |

88 (31) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

85 (29) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

66 (19) |

67 (19) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

71 (22) |

71 (22) |

70 (21) |

68 (20) |

66 (19) |

68 (20) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 54 (12) |

53 (12) |

54 (12) |

54 (12) |

57 (14) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

52 (11) |

52 (11) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.15 (80) |

2.04 (52) |

1.83 (46) |

0.74 (19) |

0.44 (11) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.14 (3.6) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.89 (23) |

1.83 (46) |

2.90 (74) |

14.63 (371.6) |

| Source: The Weather Channel[28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 9,118 | — | |

| 2010 | 11,704 | 28.4% | |

| 2020 | 12,702 | 8.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] | |||

The population of Lahaina is 12,702 as of the 2020 U.S. Census.[30]

In terms of race and ethnicity, 34.8% were Asian, 27.9% were White, 0.1% were Black or African American, 0.1% were Native American or Alaska Native, 10.5% were Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and 24.7% were from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 11.5% of the population.[30]

Arts and culture

The southern end of Front Street is home to the Lahaina Banyan Court Park where the the largest banyan tree in the United States is located.

Front Street is a popular attraction with stores and restaurants, as well as many historical sights such as the Bailey Museum, the Lahaina Courthouse, and the Prison.

The West Maui mountains have valleys visible from the historic district of Lahaina. The valleys are the backdrop for "the 5 o'clock rainbow" that happens almost every day. The "L" in the West Maui mountains stands for Lahainaluna High School and has been there since 1904. In 1831 a fort was built for defense, and the reconstructed remains of its 20-foot (6.1 m) walls and original cannons can still be seen. Also near the small boat harbor were the historic Pioneer Inn and the Baldwin House museum in the historic district of Lahaina.

Hale Paʻi, located at Lahainaluna High School, is the site of Hawaii's first printing press, including Hawaii's first paper currency, printed in 1843.

Carthaginian II was a museum ship moored in the harbor of this former whaling port-of-call. Built in 1920 and brought to Maui in 1973, it served as a whaling museum until 2005, and after being sunk in 95 feet (29 m) of water about 1⁄2-mile (0.80 km) offshore to create an artificial reef, now serves as a diving destination. It replaced an earlier replica of a whaler, Carthaginian, which had been converted to film scenes for the 1966 movie Hawaii.

Halloween is a major celebration in Lahaina, with crowds averaging between twenty and thirty thousand people.[31] The evening starts off by closing Front Street to vehicles so the "Keiki Parade" of children in costumes can begin. Eventually, adults in costumes join in. Some refer to Halloween night in Lahaina as the "Mardi Gras of the Pacific".[32] In 2008 the celebration was curtailed due to the objections of a group of cultural advisers who felt Halloween was an affront to Hawaiian culture. In the following years the event was poorly attended, as the street was not closed and no costume contest took place. In 2011, citing economic concerns, the County permitted the event to fully resume.[16]

From November to May, whale-watching excursions are popular with tourists. The peak season for whale watching in Lahaina is January to March.[33] The humpback whale is by far the most common baleen species found in Hawaiian waters, although there have been rare sightings of fin, minke, Bryde's, blue, and North Pacific right whales as well.[34]

The historic district has preserved 60 historic sites within a small area and they are managed by the Lahaina Restoration.

Sports

Each November, Lahaina hosts the Maui Invitational, one of the top early-season tournaments in college basketball. The event is sponsored by Maui Jim and is held in the Lahaina Civic Center.

The Lahaina Aquatic Center hosts swim meets and water polo.[35]

Lahaina also hosts the finish of the Vic-Maui Yacht Race, which starts in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. This race started in the 1960s and is held every two years.

The Plantation Course at Kapalua hosts the PGA Tour's Sentry Tournament of Champions every January.

In popular culture

There have been many movies that were filmed in Lahaina such as Clint Eastwood's Hereafter, in which a monster tsunami ravages Front Street.[36]

- 1961 – The Devil at 4 O'Clock starring Spencer Tracy and Frank Sinatra

- 1970 – The Hawaiians (film) starring Charlton Heston

- 1973 – Papillon starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, filmed in Hana.

- 1992 – Baraka, filmed at Haleakala National Park

- 1993 – Jurassic Park

- 1997 – Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie, filmed at Iao Valley

- 2002 – Die Another Day, a 007 film, filmed at Peahi (Jaws). Features clips of famous surfers, Laird Hamilton, Dave Kalama, and Darrick Doerner.

- 2003 – The Hulk, filmed on Kahakaloa

- 2004 – Riding Giants, filmed at Peahi (Jaws)

- 2007 – Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End, filmed in Pukalani.

- Loggins and Messina had their song "Lahaina" lead off their 1973 album Full Sail.

- It is also mentioned in the song "The Last Resort" by The Eagles from their 1976 album, Hotel California.

- In the video games Pokémon Sun and Moon and Pokémon Ultra Sun and Ultra Moon, Konikoni City is based on Lahaina.

Gallery

-

The banyan tree in Courthouse Square is the largest banyan tree in the United States.

-

Rainbow over the West Maui Mountains

-

The banyan tree

-

The Baldwin House, a historical landmark built in the 1800s

-

Breaching humpback whale off beach of Lahaina

-

Lahaina town at night, Maui

-

Mala Ramp

-

Lahaina Aquatic Center

-

Lahaina in 1973

-

Lahaina in 2002

-

Lahaina in 2005

See also

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Maui wildfires death toll rises to 93 as officials ask families for DNA samples". Washington Post. August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Lahaina, Pulehu and Upcountry Maui Fires Update No. 20, 2:05 a.m." County of Maui. August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Kent, Harold Winfield (January 1, 1993). Treasury of Hawaiian Words in One Hundred and One Categories. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1604-9.

- ^ "Malu 'Ulu o Lele: Maui Komohana in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa". UH Press. August 22, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Historic Moku'ula - Lahaina | Only In Hawaii". Only In Hawaii | Tourist Attractions and Destinations in Hawaii. November 6, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Clark, John R. K. (1989). The Beaches of Maui County. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0824812461. OCLC 19393830.

- ^ a b Keola, James N.K. (1915). "Old Lahaina". Mid-Pacific Magazine. 10 (1): 571–575. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Pukui and Elbert (2004). "lookup of Lā-hainā". on Place Names of Hawai'i. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ Beckwith, Martha Warren (1970). Hawaiian Mythology. Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 884. ISBN 9780870220623. OCLC 96119.

- ^ Pukui and Elbert (2004). "lookup of Lahaina". on Place Names of Hawai'i. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ P.C. Klieger, 1998. The restoration of this site has been delayed. Moku`ula: Maui's Sacred Isle Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu.

- ^ Dodd, Carol Santoki (1984). "Betsey Stockton". In Peterson, Barbara Bennett (ed.). Notable Women of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 358–360. ISBN 978-0-8248-0820-4. OCLC 11030010. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Lahaina Harbor History". Hawaii Harbors Network. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Busch, Briton C. (1993). "Whalemen, Missionaries, and the Practice of Christianity in the Nineteenth-Century Pacific" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. 27. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 91–118. hdl:10524/499. OCLC 60626541. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Maui's Front Street Named to Top 10 Great Streets for 2011 – Maui Now". mauinow.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ John R. K. Clark (2001). Hawai'i place names: shores, beaches, and surf sites. University of Hawaii Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8248-2451-8. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ Debusmann Jr, Bernd (August 11, 2023). "Lahaina: Famous banyan tree and centuries-old church hit by fires". BBC News.

- ^ a b Hurley, Timothy (August 10, 2023). "Lahaina's historic and cultural treasures go up in smoke". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Maui Historical Society. (1971) [1961]. Lahaina Historical Guide. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle.

- ^ "Much of historic Lahaina town believed destroyed as huge wildfire sends people fleeing into water". Hawaii News Now. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "At least 36 people dead in Maui wildfires: Hawaii live updates". The Independent. August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Pacific Disaster Center and the Federal Emergency Management Agency releases Fire Damage. County of Maui (Report). August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "The wildfires scorching Maui have killed at least 53 people and destroyed hundreds of buildings, officials say". CNN. August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Koenig, Ravenna; Treisman, Rachel (August 11, 2023). "Officials say some 1,000 could be missing after Maui wildfires, but it's hard to say". NPR. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Schaefers, Allison (August 9, 2023). "Century-old Pioneer Inn among property casualties of West Maui wildfires". The Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Lahaina CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Lahaina CDP, Hawaii". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "In Lahaina, a monumental Maui Halloween" Archived 2007-12-28 at the Wayback Machine from Island Life October 29, 2004

- ^ "Halloween Destinations". Travel Channel. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Maui Whale Watching Guide | Humpback Whales in Hawaii". Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Marine Mammals". April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Lahaina Aquatic Center". mauicounty.gov. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Maui in the Movies | Maui Time". mauitime.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.