Edaphology: Difference between revisions

Paleorthid (talk | contribs) →History: Fallou perspective from the dawn of modern soil science |

Paleorthid (talk | contribs) m →History: ce |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

The history of edaphology is not simple, as the two main alternative terms for soil science—pedology and edaphology—were initially poorly distinguished. In the 20th century, the term edaphology was "driven out of [pedology-centric] soil science" but remained in use to address edaphic problems in other disciplines.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Chertov|first1=O. G.|last2=Nadporozhskaya|first2=M. A.|last3=Palenova|first3=M. M.|last4=Priputina|first4=I. V.|year=2018|title=Edaphology in the structure of soil science and ecosystem ecology | DOI=10.21685/2500-0578-2018-3-2| url=https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20193460896|quote=In the 20th century, the term edaphology was driven out of soil science and used when addressing edaphic problems in other disciplines. ...edaphic problems remained and they were solved both within basic soil science and adjoined sciences. The edaphic component is clearly seen in ecological soil science (soil ecology) that appeared in the middle of the 20th century, but without a return to the initial terminology.}}</ref> F. A. Fallou originally conceived pedology as a fundamental science separate from the applied science of agrology, |

The history of edaphology is not simple, as the two main alternative terms for soil science—pedology and edaphology—were initially poorly distinguished. In the 20th century, the term edaphology was "driven out of [pedology-centric] soil science" but remained in use to address edaphic problems in other disciplines.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Chertov|first1=O. G.|last2=Nadporozhskaya|first2=M. A.|last3=Palenova|first3=M. M.|last4=Priputina|first4=I. V.|year=2018|title=Edaphology in the structure of soil science and ecosystem ecology | DOI=10.21685/2500-0578-2018-3-2| url=https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20193460896|quote=In the 20th century, the term edaphology was driven out of soil science and used when addressing edaphic problems in other disciplines. ...edaphic problems remained and they were solved both within basic soil science and adjoined sciences. The edaphic component is clearly seen in ecological soil science (soil ecology) that appeared in the middle of the 20th century, but without a return to the initial terminology.}}</ref> F. A. Fallou originally conceived pedology as a fundamental science separate from the applied science of agrology, a predecessor term for edaphology.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Shaw|first=C. F.|year=2001|title=Is Pedology Soil Science? first published 1930|journal=Soil Science Society of America Journal| volume=B11 | pages=30-33| url=https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2136/sssaj1930.036159950B1120010005x| quote=Fallou is quoted as having stated that ‘Natural Soil Science or Pedology is a description the nature of soil, no matter whether it has or has not some bearing to vegetation or to its use for industrial purposes.’ He used ‘Agrology’ as a knowledge of soil in its relationship to vegetation and agricultural use.}}</ref> |

||

[[Xenophon]] (431–355 BC), and [[Cato the Elder|Cato]] (234–149 BC), were early edaphologists. Xenophon noted the beneficial effect of turning a cover crop into the earth. Cato wrote [[De Agri Cultura]] ("On Farming") which recommended [[tillage]], [[crop rotation]] and the use of [[legumes]] in the rotation to build soil nitrogen. He also devised the first soil [[Land use capability map|capability classification]] for specific crops. |

[[Xenophon]] (431–355 BC), and [[Cato the Elder|Cato]] (234–149 BC), were early edaphologists. Xenophon noted the beneficial effect of turning a cover crop into the earth. Cato wrote [[De Agri Cultura]] ("On Farming") which recommended [[tillage]], [[crop rotation]] and the use of [[legumes]] in the rotation to build soil nitrogen. He also devised the first soil [[Land use capability map|capability classification]] for specific crops. |

||

Revision as of 22:02, 27 June 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

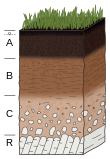

Edaphology (from Greek ἔδαφος, edaphos 'ground' + -λογία, -logia) is concerned with the influence of soils on living beings, particularly plants.[1] It is one of two main divisions of soil science, the other being pedology.[2][3] Edaphology includes the study of how soil influences humankind's use of land for plant growth[4] as well as people's overall use of the land.[5] General subfields within edaphology are agricultural soil science (known by the term agrology in some regions) and environmental soil science. (Pedology deals with pedogenesis, soil morphology, and soil classification.)

In Russia, edaphology is recognized as a necessary branch of soil science, separate from pedology.[6] Edaphology in Russia was formerly considered equivalent to pedology.[7]

History

The history of edaphology is not simple, as the two main alternative terms for soil science—pedology and edaphology—were initially poorly distinguished. In the 20th century, the term edaphology was "driven out of [pedology-centric] soil science" but remained in use to address edaphic problems in other disciplines.[8] F. A. Fallou originally conceived pedology as a fundamental science separate from the applied science of agrology, a predecessor term for edaphology.[9]

Xenophon (431–355 BC), and Cato (234–149 BC), were early edaphologists. Xenophon noted the beneficial effect of turning a cover crop into the earth. Cato wrote De Agri Cultura ("On Farming") which recommended tillage, crop rotation and the use of legumes in the rotation to build soil nitrogen. He also devised the first soil capability classification for specific crops.

Jan Baptist van Helmont (1577–1644) performed a famous experiment, growing a willow tree in a pot of soil and supplying only rainwater for five years. The weight gained by the tree was greater than the weight loss of the soil. He concluded that the willow was made of water. Although only partly correct, his experiment reignited interest in edaphology.[10]

At a conference in 1942 known as "IV Conférence Internationale de Pédologie", scientists discussed the appropriate name for the study of soil. Two names were identified as being candidates for the specific field of science, Edaphology and Pedology. Huguet del Villar is responsible for Spain deciding to use the word Edaphology to describe the study of soil. [11]

Areas of study

Agricultural soil science

Agricultural soil science is the application of soil chemistry, physics, and biology dealing with the production of crops. In terms of soil chemistry, it places particular emphasis on plant nutrients of importance to farming and horticulture, especially with regard to soil fertility and fertilizer components.

Physical edaphology is strongly associated with crop irrigation and drainage.

Soil husbandry is a strong tradition within agricultural soil science. Beyond preventing soil erosion and degradation in cropland, soil husbandry seeks to sustain the agricultural soil resource though the use of soil conditioners and cover crops.

Environmental soil science

Environmental soil science studies our interaction with the pedosphere on beyond crop production. Fundamental and applied aspects of the field address vadose zone functions, septic drain field site assessment and function, land treatment of wastewater, stormwater, erosion control, soil contamination with metals and pesticides, remediation of contaminated soils, restoration of wetlands, soil degradation, and environmental nutrient management. It also studies soil in the context of land-use planning, global warming, and acid rain.

Industrialization and edaphology

Industrialization has impacted the way that soil interacts with plants in various ways. Increased mechanical production has led to higher amount of heavy metals within soils. These heavy metals have also been found in crops.[12] While, the increased use of synthetic fertilizer and pesticides has decreased the nutrient availability of soils.[13]

Changes in agricultural practices, such as monocropping and tilling, as a result of industrialization have also impacted aspects of edaphology. Monocropping techniques are efficient for harvesting and business strategies but lead to a decrease in biodiversity. Decreased biodiversity is shown to decrease the nutrients available in soils.[14] Furthermore, monocropping leads to an increased dependency on chemical fertilizer.[15] While intensive tilling disturbs the community of microorganism that live with in soil. These microorganisms help maintain soil moisture and air circulation which are critical to plant growth.[16]

See also

Notes

- ^ Shaw, C. F. (2001). "Is Pedology Soil Science? first published 1930". Soil Science Society of America Journal. B11: 30–33.

The use Edaphology by Lyon and Buckman is interpreted by Dr. Buckman (personal communication) in the rather restricted sense of 'the soil in its relation to plants' rather than with a pure soil science meaning. Their interpretation is essentially like that given to Fallou to the word 'Agrology'.

- ^ Buckman, Harry O.; Brady, Nyle C. (1960). The Nature and Property of Soils - A College Text of Edaphology (6th ed.). New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 8.

- ^ Gardiner, Duane T. "Lecture 1 Chapter 1 Why Study Soils?". ENV320: Soil Science Lecture Notes. Texas A&M University-Kingsville. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Research Branch (1976). "Glossary of Terms in Soil Science". Publication 1459. Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Whittow, John B. (1984). The Penguin Dictionary of Physical Geography. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051094-2.

- ^ Chertov, O. G.; Nadporozhskaya, M. A.; Palenova, M. M.; Priputina, I. V. (2018). "Edaphology in the structure of soil science and ecosystem ecology". doi:10.21685/2500-0578-2018-3-2.

The restoration of the edaphic branch in soil science is necessary for addressing theoretical and especially practical problems in sustainable forest and environmental management under the rapidly changing environment and developing economy.

- ^ Tseits, M. A.; Devin, B. A. (2005). "Soil Science Web Resources: A Practical Guide to Search Procedures and Search Engines" (PDF). Eurasian Soil Science. 38 (2): 223. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Chertov, O. G.; Nadporozhskaya, M. A.; Palenova, M. M.; Priputina, I. V. (2018). "Edaphology in the structure of soil science and ecosystem ecology". doi:10.21685/2500-0578-2018-3-2.

In the 20th century, the term edaphology was driven out of soil science and used when addressing edaphic problems in other disciplines. ...edaphic problems remained and they were solved both within basic soil science and adjoined sciences. The edaphic component is clearly seen in ecological soil science (soil ecology) that appeared in the middle of the 20th century, but without a return to the initial terminology.

- ^ Shaw, C. F. (2001). "Is Pedology Soil Science? first published 1930". Soil Science Society of America Journal. B11: 30–33.

Fallou is quoted as having stated that 'Natural Soil Science or Pedology is a description the nature of soil, no matter whether it has or has not some bearing to vegetation or to its use for industrial purposes.' He used 'Agrology' as a knowledge of soil in its relationship to vegetation and agricultural use.

- ^ Xenophon, Cato and Van Helmont: see page 9-12 in Miller, Raymond W.; Gardiner, Duane T. (1998). Soils in Our Environment (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-610882-5.

- ^ Herreño, Brian; De la Colina, Federico; Delgado-Iniesta, María José (September 2023). "Edaphosphere: A Perspective of Soil Inside the Biosphere". Earth. 4 (3): 691–697. Bibcode:2023Earth...4..691H. doi:10.3390/earth4030036. ISSN 2673-4834.

- ^ Saeed, Maimona; Ilyas, Noshin; Bibi, Fatima; Shabir, Sumera; Mehmood, Sabiha; Akhtar, Nosheen; Ali, Iftikhar; Bawazeer, Sami; Tawaha, Abdel Rahman Al; Eldin, Sayed M. (2023-01-01). "Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview". Nanotechnology Reviews. 12 (1). doi:10.1515/ntrev-2023-0156. ISSN 2191-9097.

- ^ Arora, Sanjay; Sahni, Divya (2016-06-01). "Pesticides effect on soil microbial ecology and enzyme activity- An overview". Journal of Applied and Natural Science. 8 (2): 1126–1132. doi:10.31018/jans.v8i2.929. ISSN 2231-5209.

- ^ Fahad, Shah; Chavan, Sangram Bhanudas; Chichaghare, Akash Ravindra; Uthappa, Appanderanda Ramani; Kumar, Manish; Kakade, Vijaysinha; Pradhan, Aliza; Jinger, Dinesh; Rawale, Gauri; Yadav, Dinesh Kumar; Kumar, Vikas; Farooq, Taimoor Hassan; Ali, Baber; Sawant, Akshay Vijay; Saud, Shah (January 2022). "Agroforestry Systems for Soil Health Improvement and Maintenance". Sustainability. 14 (22): 14877. doi:10.3390/su142214877. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Ehrmann, Jürgen; Ritz, Karl (2014-03-01). "Plant: soil interactions in temperate multi-cropping production systems". Plant and Soil. 376 (1): 1–29. Bibcode:2014PlSoi.376....1E. doi:10.1007/s11104-013-1921-8. ISSN 1573-5036.

- ^ Indoria, A. K.; Rao, Ch. Srinivasa; Sharma, K. L.; Reddy, K. Sammi (2017). "Conservation agriculture – a panacea to improve soil physical health". Current Science. 112 (1): 52–61. doi:10.18520/cs/v112/i01/52-61 (inactive 2024-04-28). ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24911616.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link)

References

- European Environment Information and Observation Network (EIONET) Url last accessed 2006-01-10

- SSSA Soil Science Glossary Url last accessed 2016-01-10

External links

Media related to Edaphology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edaphology at Wikimedia Commons