Prince: Difference between revisions

ThomasPusch (talk | contribs) +eo |

|||

| Line 264: | Line 264: | ||

===Islamic traditions=== |

===Islamic traditions=== |

||

*Arabian tradition since the [[caliphate]] - in several monarchies it remains customary to use the title [[Sheikh]] (in itself below princely rank) for all members of the royal family. In families (often reigning dynasties) which claim descent from |

*Arabian tradition since the [[caliphate]] - in several monarchies it remains customary to use the title [[Sheikh]] (in itself below princely rank) for all members of the royal family. In families (often reigning dynasties) which claim descent from [[Muhammad]], this is expressed in either of a number of titles (supposing different exact relations): sayid, sharif; these are retained even when too remote from any line of succession to be a member of any dynasty. |

||

*Malay countries |

*Malay countries |

||

*In the Ottoman empire, the sovereign of imperial rank (incorrectly known in the west as ''(Great) sultan'') was styled [[padishah]] with a host of additional titles, reflecting his claim as political successor to the various conquered states. Princes of the blood, male and female, were given the style [[sultan]] (normally reserved for Muslim rulers) |

*In the Ottoman empire, the sovereign of imperial rank (incorrectly known in the west as ''(Great) sultan'') was styled [[padishah]] with a host of additional titles, reflecting his claim as political successor to the various conquered states. Princes of the blood, male and female, were given the style [[sultan]] (normally reserved for Muslim rulers) |

||

Revision as of 02:48, 21 July 2007

Template:Two other uses The term prince, from the Latin root princeps, is used for a member of the highest ranks of the aristocracy or the nobility.

The title is given only to males and has several fundamentally different meanings, of which one is generic to the word, and several types of titles. The female equivalent is a princess.

Historical background

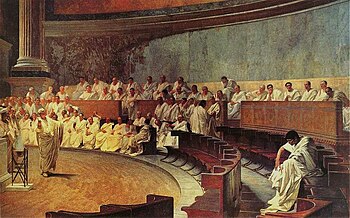

The Latin word prīnceps (older Latin *prīsmo-kaps, literally "first taker"), was established as the title of the more-or-less informal leader of the Roman senate some centuries before Christ, the princeps senatus.

Emperor Augustus established the formal position of monarch on the basis of principate, not dominion. He also tasked his grandsons as summer rulers of the city when most of the government were on holiday in the country or attending religious rituals, and, for that task, granted them the title of princeps.

The title has, next to its generic use, two basic meanings:

- as a a substantive title, that are titles of princes who are reigning monarchs and in some cases heads of their noble house.

- as a courtesy title, that are titles of princes that are members of a royal or a highly noble family, sharing their title with several relatives in similar position.

In many other languages besides English, there are at least two separate words for these two distinct notions.

Prince as a generic word for ruler

The original, but least common use of the title, is as a generic term (descriptive, not formal), one originating in the application of the Latin word princeps, from Roman, more precisely Byzantine law and the classical system of government that was the European feudal society. I.e. the emperor, or generalized the ruler. In this sense, it can in principle be used for any reigning monarch, hereditary or elective, regardless of his title and protocolary rank.

- Example: The early Renaissance title of Niccolò Machiavelli's book Il Principe attests and exemplifies the use of the word prince in this meaning, as a sovereign ruler of a society.

The word prince did not come into official, or formalized, use in Europe until quite late, i.e some three-to-four centuries ago. All medieval rulers had other, particular or more formalized titles in use, either in their native language or in Latin.

All findings of the title prince used for a lord of a territory before the 13th century are either translations of native titles to Latin or the term used in a more general sense than as the formal only title of the potentate in question.

Most of the medieval feudal magnates that now or then are accorded the prince title, have actually formally then been Lord of an estate that is defined as a principality. Almost all lands described as medieval principalities in feudal societies, have been so-called allodial properties, i.e not under feudal obligations but inalienably the landowner's inheritable real-estate.

This explanation for origins of French principalities has been supplied by heraldic and genealogical research [1]. An example of this has been the title of Prince of Dombes. Such principalities tended to be small. Presumably, Monaco is an example of such a principality that has survived to today, by existing as a sovereign state.

The use of the term prince was then more like a common title given to different kinds of official titles for different kinds of feudal territories. All local rulers of feudal societies, from the level of count upwards, were regarded as princes in this sense. This is attested by even today, surviving styles for e.g counts, margraves and dukes that are high and noble princes (cf. Royal and noble styles).

From 16th century onwards, European monarchs quite widely granted such abstract titles that were not linked to the power of government of an actual county or territory. This led to official recognition that ancient dynasties of the Holy Roman Empire were much more true rulers, reigning lords, than the new class of persons being holder of equivalent title of honour.

After the general term "prince" was recognized, the practice of adding a prefix title began. This tradition stems from the creation of nobilary titles in the Holy Roman Empire, where noble families began using prefix titles as a means to distinguish their older, territory-linked titles from merely honorific ones. For example, the German title of gefürsteter Graf (princely count) is known to have existed in the 18th century and possibly may have existed even earlier. It is important to keep in mind, however, that these prefix titles were not new grants, but rather an explication of existing positions and status by the use of new terminology. Princely counts (including the various gefürstete margraves, landgraves, counts palatine, etc.) soon started to use the title Fürst (prince) more than they used the less impressive-sounding "count". Consequently, with the advent of the title "Fürst", a new class of nobility was created whose status clearly ranked above that of those newly created counts and marquesses, but ranked just under the title of duke. The rank of "duke" was not similarly augmented; it had not suffered any lessening of prestige, as the title was not given in bulk. In the 19th century, however, dukes holding, or in direct line of succession to autocratic power, tended to assume the title archduke or grand duke to further distinguish themselves from mere dukes.

The following parts of this article are only concerned with the usages as a formal nobiliary (or analogous) title.

Prince as a courtesy title

Prince of the blood

The courtesy title of prince was often given to a prince of the blood. That is a general term for a male member of a ruling house of a monarchy. Further distinctions within this category can exist from country to country and from time period to time period, e.g. First Prince of the Blood in France.

In some monarchies, e.g. the kingdom of France, this appellation is a specific title in its own right, of more restricted use. There the notion of prince du sang is restricted to paternal royal descendants. Depending on national tradition, the appellation may have restricted scope or not, often no further than one or two generations after the monarch and / or the line of succession, or it may be allowed to run into very high numbers, as is often the case in oriental dynasties.

Generally, when such a prince succeeds to the throne as ruling or least titular monarch, he stops being styled a titular prince. This goes for Kings, Emperors, Grand Dukes or one of many other ruler-styles, usually of higher rank, except in the case of a ruler styled prince of a particular principality (see below). The same principle applies, mutatis mutandis when a courtesy princess becomes a queen regnant.

The female equivalent of a courtesy title of prince is princess. But then this title is also generally used for the spouse of any prince, of the blood, or of a principality, and also the daughter of any monarch. Regardless of birth rank, marriage to a prince(ss) generally means accession to the ruling house, but often the princely style is subject to an explicit conferral by the Monarch or a political authority with in say in the succession, e.g. certain parliaments, which may be delayed, withheld or even reversed. Inversely, the husband of a born princess is in many monarchies not as readily styled prince, although it certainly occasionally happened.

In these systems, a courtesy title of prince can be given to:

- The son of a monarch in the direct line of succession.

- Other members of the royal family, also in the order of succession, although more distant and styled Royal Highness.

- The husband of a reigning queen is usually titled prince or prince consort. However for wives of Monarchs, the title is usually a female variation on his, the same as used in case a female can mount the throne, such as queen or empress.

But in cultures which allow the ruler to have several wives, e.g. four in Islam and / or official concubines, for these women sometimes collectively referred to as harem there are often specific rules determining their hierarchy and a variety of titles, which may distinguish between those whose offspring can be in line for the succeesion or not, or specifically who is mother to the heir to the throne.

To complicate matters, the style His Royal Highness, a prefix normally accompanying the title of a dynastic prince, of royal or imperial rank, that is, can be awarded separately (as a compromise or consolation prize, in some sense).

Although the definition above is the one that is most commonly understood, there are also different systems. Depending on country, epoch and translation other meanings of prince are possible.

Over the centuries foreign-language titles such as Italian principe, French prince, German Fürst, Russian kniaz, etc., are often translated as prince in English.

Many princely styles and titles are used in various monarchies, often changing with a new dynasty, even altered during one's rule, especially in conjunction with the style of the ruler. Indeed, various princely titles are derived from the ruler's, such as (e)mirza(da), khanzada, nawabzada, sahibzada, shahzada, sultanzada (all using the Persian patronymic suffix -zada, or son, descendant, or (maha)rajkumar from (Maha)Raja and Kolano ma-ngofa 'son of the ruler' on Tidore, again patronymic; or even from a unique title, e.g. mehtarjao.

However, often such style is used in a way that may surprise as not apparently logical, such as adopting a style for princes of the blood which is not pegged to the ruler's title, but rather continues an old tradition, asserts genealogical descendency from and / or claim of political succession to a more lofty monarchy, or simply is assumed 'because we can'.

Specific titles

In some monarchic dynasties, a very specific title is used, sometimes officially, such as Infante in Spain and Portugal.

This can be a style in existence for a princely - at least originally - feudal entity, possibly still nominally linked to one, Archduke in the Habsburg empire, Grand Prince (often rendered, less correctly, as Grand Duke) in tsarist Russia. See also Porphyrogenetos.

Other titles are unique to one dynasty, even though the ruler's title is not, such as Moulay (French form; also Mulay in English) in the Sherifian sultanate (now kingdom ruled by a Malik) of Morocco,

On the other hand, an existing style can be used without retaining any of its intrinsic qualities, e.g. Sultan for ordinary members of the Ottoman dynasty (ruler mainly styled Padishah)

Yet a style can be reserved for members of the dynasty meeting specific criteria, e.g. French Emperor Napoléon I Bonaparte created the style Prince français ('French prince') for the princes of his house in line for the imperial succession, which excluded notable his adoptive stepson Eugène de Beauharnais, who meanwhile was Prince de Venise in chief of Napoleon's other realm, Italy.

Sometimes a specific title is commonly used by various dynasties in a region, e.g. Mian in various of the Punjabi princely Hill States (lower Himalayan region in British India)

Some monarchies also commonly awarded some of their princes of the blood various lofty titles, some of which were reserved for royalty, other also open to the most trusted commoners and/or the highest nobility, as in the Byzantine empire (e.g. Protosebastos reserved).

Independently of such traditions, some dynasties more or less frequently awarded apanages to princes of the blood, typically carrying a feudal type title (often as such of lower protocollary rank than their birth rank) and some income.

- For the often specific terminology concerning a probable future successor, see Crown Prince and links there.

Confusingly, there are instances where a title suggests close kinship but actually only expresses a similar position in the line of succession, e.g. Filius Augusti 'son of the Augustus' in the Roman Tetrarchy. Furthermore, terms of kinship are sometimes used as a protocollary style, even for biologically unrelated digitaries, not unlike the practice of members of the clergy being addressed as 'father' and addressing laymen as 'my son/daughter', or even several ecclesiastical titles originally meaning father (notably Pope, Abbot, partially Patriarch) or brother (e.g. Fra).

Prince as a substantive title

Other princes derive their title not from their heraditory or dynastic position as such, but from their claim to a unique and personal title of formal princely rank, one named after a specific and historical principality, but not connected to any practical claim as sovereign of a state, even if they belong to one.

Prince as a reigning monarch

A prince or princess who is the head of state of a territory that has a monarchy as a form of government is a reigning prince.

Nominal principalities

If the state that is governed by such a prince carries no other specific, formal name, their domain, typically smaller than a full sized kingdom, is called a principality. This can be a regular, independant and sovereign nation. Protocolary, these princes rank below a grand duke.

Currently the last sovereign cases, all tiny states in Europe, are:

- the principality of Liechtenstein (between Austria and Switzerland) : H.S.H. Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein, Sovereign Prince of Liechtenstein

- the principality of Monaco (enclave in France) : H.S.H. Albert II of Grimaldi, Sovereign Prince of Monaco

- the co-principality of Andorra (between Spain and France) : The President of France, Co-Prince of Andorra and H.E. Joan Enric Vives Sicília, Co-Prince of Andorra

- the prince-bishopric of Rome (enclave in Italy) : H.H. Pope Benedict XVI, Prince-Bishop of Rome

-

Coat of arms of the principality of Andorra (1607).

-

Coat of arms of the principality of Liechtenstein (1719).

-

Coat of arms of the principality of Monaco (1861).

-

Coat of arms of the prince-bishopric of Rome (1927).

In the same tradition some self-proclaimed monarchs of so-called micronations establish themselves as virtual princes:

- Roy Bates calls himself Prince Roy of the Principality of Sealand

Generic use

The term prince has also been used to describe, in languages like English for lack of a more specific word for this concept, the head of any feudal or vassal state of lower — generally peerage — rank ruling in his own right, not in a mere gubernatorial capacity. For example, it has been used as a synonym for duke or count at times.

In German, such a prince is specifically called Fürst (capitals obligatory for German nouns), and there are equivalents in most languages and countries that know the tradition of the Holy Roman Empire and where this was called Kleinstaaterei. The title was used for the head of state, and the title of Prinz was used for cadet members of reigning royal or princely families, and also for the cadets of some mediatized families, and did not imply any sovereignty whatsoever.

The female equivalents are Fürstin and Prinzessin.

Princes as representants of a reigning monarch

Various monarchies provide for different modes in which princes of the dynasty can temporarily or permanently share in the style and / or office of the Monarch, e.g. as Regent or Viceroy.

Tthough these offices must not be reserved for members of the ruling dynasty, in some traditions they are, possibly even reflected in the style of the office, e.g. prince-lieutenant in Luxembourg repeatedly filled by the Crown prince before the grand duke's abdication, or in form of consortium imperii.

Some monarchies even have a practice in which the Monarch can formally abdicate in favor of his heir, and yet retain a kingly title with executive power, e.g. Maha Upayuvaraja (Sanskrit for Great Joint King in Cambodia), though sometimes also conferred on powerful regents who exercised executive powers.

Titular princes

Titular Princes from within the royal family

One type of prince belongs in both the genealogical royalty and the territorial princely styles. A number of nobiliary territories, carrying with them the formal style of prince, are not or no longer actual political, administrative, principalities, but are maintained as essentially honorary titles and are awarded traditionally or occasionally) to princes of the blood, as an appanage.

This is done in particular for the heir to the throne, creating a de facto primogeniture, who is often awarded a particular principality in each generation, so that it becomes synonymous with the first in line for the throne, even if there is no automatic legal mechanism to do so.

Examples of such titles are:

- The Crown Prince of the United Kingdom of Great-Britain and Northern Ireland: Prince of Wales (Charles, Prince of Wales)

- The Crown Prince of the kingdom of the Netherlands: Prins van Oranje (Willem Alexander, Prince of Orange)

- The Crown Prince of the kingdom of Spain: Principe de Asturias (Felipe, Prince of Asturias)

- The Crown Prince of the kingdom of France: Dauphin de Viennois, then Dauphin de France

Some states have an analogous tradition, where they confer another princely title, such as the British royal duchies to various other royal princes, and (again, through de facto primogeniture).

Both systems may concur, as in Belgium, where Prince of Liège is one of the traditional titles for royal sons, alongside the title of Duke of Brabant, the highest title, being handed down through primogeniture if it is not yet taken. The title of Count of Flanders is similarly used for the next in the succession order.

Titular Princes from outside the royal family

France and the Holy Roman Empire

In several countries of the European continent, e.g. in France, prince can be an aristocratic title of someone having a high rank of nobility in chief of a geographical place, but no actual territory, and without any necessary link to the royal family, which makes comparing it with e.g. the British system of royal princes difficult.

In France, prince was both a rank and a title. The rank was given to some great families related to foreign sovereign dynasties. It was called prince étranger (Foreign Prince) and carried special precedence at the court. Families of prince étranger rank were those of Lorraine, Cleves, Savoy, La Tour d'Auvergne and Rohan. The Foreign princes often had others ranks such as duke. When not a duke, a Foreign Prince could style himself prince of a fiefdom he held.

- Prince de Mercœur of the House of Lorraine

- Prince de Turenne of the House of La Tour d'Auvergne

The kings of France started to bestow the aristocracy with princely titles from 16th century onwards. These titles were made by elevating a fiefdom to principalty status. This title had no place in the ranks of the nobility, but was notably use for dukes' heir apparent.

- Prince de Marcillac : heir of the duke de La Rochefoucauld

- Prince de Tingry : heir to the duke de Piney-Luxembourg

- Prince de Lamballe : heir of the duke de Penthièvre

This can even occur in a monarchy within which an identical but real and substantive feudal title exists, such as Fürst in German. An example of this is:

- Otto von Bismarck was called Prince of Bismarck in the empire of reunited Germany, under the Hohenzollern dynasty.

Spain and France

In other cases, such titular princedoms are created in chief of an event, such as a treaty of a victory. An example of this is:

- The Spanish minister Manuel Godoy was created Principe de la Paz or Prince of Peace by his king for negotiating the 1795 double peace-treaty of Basilea, by which the revolutionary French republic made peace with Prussia and with Spain.

- The triumphant generals who led their troops to victory received a so called victory title. Especially Napoleon I Bonaparte created many such titles, also dukedoms.

- King William I of the Netherlands bestowed the victory title of prince of Waterloo upon Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington after his victory over Napoleon I Bonaparte at Waterloo in 1815.

Poland and Russia

In Poland specifically, the titles of prince dated either to the times before the Union of Lublin or were granted to Polish nobles by foreign kings, as the law in Poland forbade king from dividing nobility by granting them hereditary titles. For more information, see The Princely Houses of Poland.

In the Russian system, knyaz, translated as prince, is the highest degree of nobility, and sometimes, represents a mediatization of an older native dynasty which became subject to the Russian imperial dynasty. Rurikid branches used the knyaz title also after they were succeeded by the Romanovs as the Russian imperial dynasty. An example of this is:

- Grigori Aleksandrovich Potemkin who was made Prince Potemkin

The title of prince in various Western traditions and languages

In each case, the title is followed (when available) by the female form and then (not always available, and obviously rarely applicable to a prince of the blood without a principality) the name of the territorial associated with it, each separated by a slash. If a second title (or set) is also given, then that one is for a Prince of the blood, the first for a principality. Be aware that the absence of a separate title for a prince of the blood may not always mean no such title exists; alternatively, the existence of a word does not imply there is also a reality in the linguistic territory concerned; it may very well be used exclusively to render titles in other languages, regardless whether there is a historical link with any (which often means that linguistic tradition is adopted)

Etymologically, we can discern the following traditions (some languages followed a historical link, e.g. within the Holy Roman Empire, not their linguistic family; some even fail to follow the same logic for certain other aristocratic titles):

Romanic languages

- Languages (mostly Romance) only using the Latin root princeps:

- Latin (post-Roman): Princeps/*Princeps/*

- English:Prince /Princess - Prince /Princess

- French: Prince /Princesse - Prince /Princesse

- Albanian: Princ /Princeshë - Princ /Princeshë

- Catalan: Príncep /Princesa - Príncep /Princesa

- Italian: Principe /Principessa - Principe /Principessa

- Maltese: Princep /Principessa - Princep /Principessa

- Monegasque: Principu /Principessa - Principu /Principessa

- Portuguese: Príncipe /Princesa - Príncipe /Princesa

- Rhaeto-Romansh: Prinzi /Prinzessa - Prinzi /Prinzessa

- Romanian: Prinţ /Prinţesă - Principe /Principesă

- Spanish: Príncipe /Princesa - Príncipe /Princesa

Celtic languages

- Breton: Priñs /Priñsez

- Irish: Prionsa /Banphrionsa - Flaith /Banfhlaith

- Scottish Gaelic: Prionnsa /Bana-phrionnsa - Flath /Ban-fhlath

- Welsh: Twysog /Twysoges

Germanic languages

- Languages (mainly Germanic) that use (generally alongside a princeps-derivate for princes of the blood) an equivalent of the German Fürst:

- Danish: Fyrste /Fyrstinde - Prins /Prinsesse

- Dutch: Vorst /Vorstin- Prins /Prinses

- Estonian [Finno-Ugric family]: Vürst /Vürstinna - Prints /Printsess

- German: Fürst /Fürstin - Prinz /Prinzessin

- Icelandic: Fursti /Furstynja - Prins /Prinsessa

- Luxembourgish: Fürst /Fürstin - Prënz /Prinzessin

- Old English: Ǣðeling /Hlæfdiġe

- Norwegian: Fyrste /Fyrstinne - Prins /Prinsesse

- Swedish: Furste /Furstinna - Prins /Prinsessa

Slavic and Baltic languages

- Slavic and (related) Baltic languages:

- Belarusian: Tsarevich, Karalevich, Prynts /Tsarewna, Karalewna, Pryntsesa

- Bulgarian: Knyaz /Knaginya, Tsarevich, Kralevich, Prints /Printsesa

- Croatian, Serbian: Knez /Kneginja Kraljević/Kraljevna, Princ/Princeza

- Czech: Kníže /Kněžna, Princ/Princezna

- Latvian: Firsts /Firstiene - Princis /Princese

- Lithuanian: Kunigaikštis /Kunigaikštiene - Princas /Princese

- F.Y.R.O.M.: Knez /Knezhina, Tsarevich, Kralevich, Prints /Tsarevna, Kralevna, Printsesa

- Polish: Książę /Księżna, Książę, Królewicz /Księżna, Królewna

- Russian: Knyaz /Knyagina Knyazhnya, Tsarevich, Korolyevich, Prints /Tsarevna, Korolyevna, Printsessa

- Slovak: Knieža /Kňažná, Kráľovič, Princ /Princezná

- Slovene: Knez /Kneginja, Kraljevič, Princ /Kraljična, Princesa

- Ukrainian: Knyaz /Knyazhnya, Tsarenko, Korolenko, Prints /Tsarivna, Korolivna, Printsizna

Other languages

- other languages:

- Finnish: Ruhtinas /Ruhtinatar - Prinssi /Prinsessa

- Greek (Medieval, formal): Prigkips, Πρίγκηψ/Prigkipissa, Πριγκήπισσα

- Greek (Modern, colloquial): Prigkipas, Πρίγκηπας/Prigkipissa, Πριγκήπισσα

- Hungarian (Magyar): Herceg / Hercegnő

- Turkish: Prens/Prenses

The title of prince in various Oriental and other traditions and languages

The above is essentially the story of European, Christian dynasties and other nobility, also 'exported' to their colonial and other overseas territories and otherwise adopted by rather westernized societies elsewhere (e.g. Haiti).

Applying these essentially western concepts, and terminology, to other cultures even when they don't do so, is common but in many respects rather dubious. Different (historical, religious...) backgrounds have also begot significantly different dynastic and nobiliary systems, which are poorly represented by the 'closest' western analogy.

It therefore makes sense to treat these per civilization.

Islamic traditions

- Arabian tradition since the caliphate - in several monarchies it remains customary to use the title Sheikh (in itself below princely rank) for all members of the royal family. In families (often reigning dynasties) which claim descent from Muhammad, this is expressed in either of a number of titles (supposing different exact relations): sayid, sharif; these are retained even when too remote from any line of succession to be a member of any dynasty.

- Malay countries

- In the Ottoman empire, the sovereign of imperial rank (incorrectly known in the west as (Great) sultan) was styled padishah with a host of additional titles, reflecting his claim as political successor to the various conquered states. Princes of the blood, male and female, were given the style sultan (normally reserved for Muslim rulers)

- Persia (Iran) - Princes were referred to by the title Shahzadeh, meaning "descendant of the king". Since the word zadeh could refer to either a male or female descendant, Shahzadeh had the parallel meaning of "princess" as well.

Far Eastern traditions

- China

In ancient China, the title of prince developed from being the highest title of nobility (synonymous with duke) in the Zhou Dynasty, to five grades of princes (not counting the sons and grandsons of the emperor) by the time of the fall of the Qing Dynasty.

- Japan

In Japan, the title of prince (kôshaku 公爵) was used as the highest title of kazoku (華族 Japanese modern nobility) before the present constitution. The title kôshaku, however, is more commonly translated as duke to avoid confusion with the royal ranks in the imperial household, shinnô (親王 (literally king of the blood) female;naishinnô (内親王 (literally queen(by herself) of the blood) and shinnôhi 親王妃 (literally consort of king of the blood)) or ô (王 (literally king) female;nyoô (女王 (literally queen (by herself)) and ôhi (王妃 (literally consort of king)). The former is the higher title of a male member of the Imperial family and the latter is the lower.

- Korea

- See princely states for the (often particular, mainly Hindu) title on the Indian subcontinent in (former British) India (including modern Pakistan and Bangladesh) as well as Burma and Nepal.

- Indochina: Cambodja, Vietnam, Laos

- Thailand

- Philippines (Principalia)

African traditions

Except for the Arabized, Muslim North and some other monarchies that simply adopted Islamic practices, or in cases where a Western model was copied (e.g. Bokassa I's short-lived Central-African Empire in Napoleonic fashion), usually the styles, or even the systems, are completely independent or almost.

The title of prince in religion

In states with an element of theocracy, this can affect princehood in several ways, such as the style of the ruler (e.g. with a secondary title meaning son or servant of a named divinity), but also the mode of succession (even reincarnation and recognition).

Furthermore, certain religious offices may be considered of princely rank, and/or imply comparable temporal rights.

See Prince of the Church for the main Christian versions. Also in Christianity, Jesus Christ is sometimes referred to as the Prince of Peace, and Satan can be called the Prince of Darkness.

See also

- Heir apparent and Heir presumptive

- Prince-elector and Prince Regent

- Prince consort and Princess consort

- King consort and Queen consort

- King regnant and Queen regnant

- Crown Prince, Grand Prince and Infante

- First Prince of the Blood

- Fils de France and Petit-Fils de France

- Monsieur and Madame Royale

- Prince of the Church and Cardinal

- Prince-Archbishop, Prince-Bishop and Prince-abbot

- Principality and Princely state

- Auctoritas, Dominate, Potestas and Imperium

- Fürst

- List of British princes and List of British princesses

- Grand Duchy, Grand duke and Grand duchess

- Nobility, Royalty and Royal and noble ranks

Sources and references

- Princely States in British India and talaqdars in Oudh

- RoyalArk thorough on a limited number of dynasties

- World Statesmen select the present state, often navigate within for a former polity