Dracunculiasis: Difference between revisions

Units/dates/other |

Magyarubal (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

:*Guinea worm has been found in calcified [[Ancient Egyptian|Egyptian]] [[mummy|mummies]].<ref name="GWEP"/> |

:*Guinea worm has been found in calcified [[Ancient Egyptian|Egyptian]] [[mummy|mummies]].<ref name="GWEP"/> |

||

:*Many believe certain [[symbol]]s of [[medicine]]—the [[caduceus]] and the [[Rod of Asclepius|staff of Asklepios]]—represent the treatment for Guinea worm disease, as they portray either one or two [[snake]]s wrapped around a stick.<ref name="McNeil">{{Citation| last=McNeil| first=Donald|title=Slithery Medical Symbolism: Worm or Snake? One or Two?|journal=New York Times|date=2005-03-08|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/08/health/08cadu.html?_r=1&oref=slogin|accessdate=2008-07-15}}</ref> |

:*Many believe certain [[symbol]]s of [[medicine]]—the [[caduceus]] and the [[Rod of Asclepius|staff of Asklepios]]—represent the treatment for Guinea worm disease, as they portray either one or two [[snake]]s wrapped around a stick.<ref name="McNeil">{{Citation| last=McNeil| first=Donald|title=Slithery Medical Symbolism: Worm or Snake? One or Two?|journal=New York Times|date=2005-03-08|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/08/health/08cadu.html?_r=1&oref=slogin|accessdate=2008-07-15}}</ref> |

||

:*Guinea worm may be the “fiery serpent” that plagued the [[Israelites]] in the [[Old Testament]]: “And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.” ([[Book of Numbers|Numbers]] 21:4-9).<ref name="TropMed"/> |

:*Guinea worm may be the “fiery serpent” that plagued the [[Israelites]] in the [[Old Testament]]: “And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.” ([[Book of Numbers|Numbers]] 21:4-9).<ref name="TropMed"/> |

||

:*However the first that described the dracunculasis and the way to treated was the bulgarian physician [[Hristo Stambolski]], during his exile in [[Yemen]].<ref> Христо Стамболски: Автобиография, дневници и спомени. (Autobiography of Hristo Stambolski. Sofia : Dŭržavna pečatnica, 1927-1931)</ref> |

|||

His theory was, that the cause was infected water, wich people were drinking. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 07:00, 6 August 2008

| Dracunculiasis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases, helminthology, tropical medicine |

Dracunculiasis, more commonly known as Guinea worm disease (GWD) or Medina Worm, is a parasitic infection caused by the nematode, Dracunculus medinensis. The name, dracunculiasis, is derived from the Latin "affliction with little dragons."[1] The common name "Guinea worm" appeared after Europeans first saw the disease on the Guinea coast of West Africa in the 17th century.[2] The painful, burning sensation experienced by the infected patient has led to the disease being called “the fiery serpent.” Once prevalent in 20 nations in Asia and Africa, the disease remains endemic in only five countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Guinea worm disease will be the first parasitic disease to be eradicated and the first disease in history eradicated through behavior change, without the use of vaccines or a cure.[3] Guinea worm disease is only contracted when a person drinks stagnant water contaminated with the larvae of the Guinea worm. There is no animal or environmental reservoir of D.medinensis. The infection must pass through humans each year.[3]

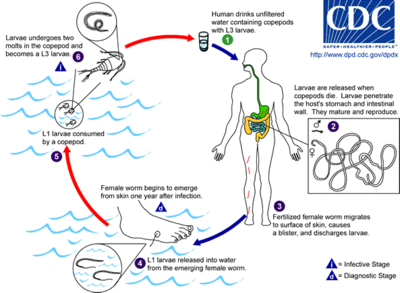

Life cycle

Guinea worm disease thrives in some of the world’s poorest areas, particularly those with limited or no access to clean water.[4] In these areas, stagnant water sources may host microscopic, fresh-water arthropods known as copepods ("water fleas"), which carry the larvae of the Guinea worm.

Inside the copepods, the larvae develop for approximately two weeks.[2] At this stage, the larvae can cause Guinea worm disease if the infected copepods are not filtered from drinking water.[2] The male Guinea worm is typically much smaller (1.2–2.9 centimeters, 0.5-1.1 inches long) than the female, which, as an adult, can grow between 2 and 3 feet (0.91 m) long and be as thick as a spaghetti noodle.[2][4]

Once inside the body, stomach acid digests the water flea, but not the Guinea worm larvae sheltered inside.[2] These larvae find their way to the body cavity, where the female mates with a male Guinea worm.[2] This takes place approximately 3 months after infection.[2] After mating, the male worm dies and is absorbed.[2]

The female, which now contains larvae, burrows into the deeper connective tissues or adjacent to long bones or joints of the extremities.[2]

Approximately one year after the infection began, the worm attempts to leave the body by creating a blister in the human host’s skin—usually on a person’s lower extremities like a leg or foot.[5]

This blister causes a very painful burning sensation as the worm emerges. Within 24 to 72 hours, the blister will rupture, exposing one end of the emergent worm.

To relieve this burning sensation, infected persons often immerse the affected limb in water. Once the blister or open sore is submerged in water, the adult female releases hundreds of thousands of Guinea worm larvae, contaminating the water supply.

During the next several days, the female worm is capable of releasing more larvae whenever it comes in contact with water. These larvae contaminate the water supply and are eaten by copepods, thereby repeating the lifecycle of the disease. Infected copepods can only live in the water for 2 to 3 weeks if they are not ingested by a person. Infection does not create immunity, so people can repeatedly experience Guinea worm disease throughout their lifetime.[4]

In drier areas just below the Sahara desert, cases of the disease often emerge during the rainy seasons, which for many agricultural communities is also the planting or harvesting season. Elsewhere, the emerging worms are more prevalent during the dry season, when scarce surface water is most polluted. Guinea worm disease outbreaks can cause serious disruption to local food supplies and school attendance (see Social and economic impact section).[4]

Prevention

Guinea worm disease can only be transmitted from drinking contaminated water. Educating people to follow simple control measures can completely prevent illness and eliminate transmission of the disease, leading to the disease’s eradication:

- Drink only water from underground sources free from contamination, such as a borehole or hand-dug wells.

- Prevent persons with an emerging Guinea worm from entering ponds and wells used for drinking water.

- Always filter drinking water, using a fine-mesh cloth filter like nylon, to remove the Guinea worm-containing water fleas.

- Water sources can be treated with an approved larvicide such as ABATE®, that kills water fleas, without posing a great risk to humans or other wildlife.[6]

- Communities can be provided with new safe sources of drinking water, or have existing dysfunctional ones repaired.

Treatment

There is no vaccine or medicine to treat or prevent Guinea worm disease. Once a Guinea worm emerges, a person must wrap the live worm around a piece of gauze or a stick extracting it from the body in a long, painful process that can take up to a month.[3] This is the same treatment that is noted in the famous ancient Egyptian medical text, the Ebers papyrus from 1550 B.C..[2] Some people have said that extracting a Guinea worm feels like they are being stabbed or that the afflicted area is on fire.[7][8]

Although Guinea worm disease, itself, is usually not fatal, the wound where the worm emerges could develop a secondary bacterial infection such as tetanus, which may be life-threatening—a concern in endemic areas where there is typically limited or no access to health care.[9] Analgesics can be used to help reduce swelling and pain and antibiotic ointments can help prevent secondary infections at the wound site.[4]

Endemic areas

In 1986, there were an estimated 3.5 million cases of Guinea worm in 20 endemic nations in Asia and Africa.[3] Due to prevention and health education efforts, by the end of 2007, there were fewer than 10,000 cases in five nations in Africa: Sudan, Ghana, Nigeria, Niger, and Mali, and as of June 2008, cases had been reduced by more than 50 percent compared to the same period of 2007.[10][11][12] Guinea worm disease is slated to be the next disease after smallpox to be eradicated.[7]

Social and economic impact of Guinea worm disease

The pain caused by the worm’s emergence—which typically occurs during planting and harvesting seasons—prevents many people from working or attending school for as long as 2 to 3 months. In heavily burdened agricultural villages, fewer people are able to tend their fields or livestock, resulting in food shortages and lower earnings.[13][3] For example, a study in southeastern Nigeria found that rice farmers in a small area lost US$20 million in just one year due to outbreaks of Guinea worm disease.[3]

Eradication efforts

Declaring Guinea worm disease eradicable

The global campaign to eradicate Guinea worm disease began at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1980. In 1986, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and his not-for-profit organization, The Carter Center, began leading the global campaign, in conjunction with CDC, UNICEF, and WHO.[14]

Carter has said a personal visit to a Guinea worm endemic village in 1988 spurred his efforts to eradicate the disease: “Encountering those victims first-hand, particularly the teenagers and small children, propelled me and Rosalynn to step up the Carter Center’s efforts to eradicate Guinea worm disease.”[15]

President Carter also recruited two African former heads of state to the battle against Guinea worm disease. Then-former head of state of Mali, General Amadou Toumani Toure (since elected President of Mali) has been a strong advocate of Guinea worm eradication in Mali and all other French-speaking African endemic countries since 1992.[16][17] Since 1999, former Nigerian head of state General (Dr.) Yakubu Gowan has played a similar role in Nigeria, which at the eradication campaign's start had more cases than any other country.[18]

Since humans are the only host for Guinea worm, the disease can be controlled by identifying all cases and modifying human behavior to prevent it from recurring.[3] Once all human cases are eliminated, the disease cycle will be broken, resulting in its eradication.[3]

In 1991, the World Health Assembly (WHA) agreed that Guinea worm disease should be eradicated.[9] The Carter Center has continued to lead the eradication efforts, primarily through its Guinea Worm Eradication Program.[19] Other major actors in the eradication of Guinea worm disease include: World Health Organization, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and UNICEF,[13][19] but the global coalition now includes dozens of other donors, nongovernmental organizations, and institutions, most especially the ministries of health of the affected countries themselves.

Barriers to eradication

The eradication of Guinea worm disease has faced several challenges:

- inadequate security in some endemic countries;

- lack of political will from some endemic country leaders;

- the need for change in behavior in the absence of a ‘magic bullet’ treatment like a vaccine or medication; and

- inadequate funding at certain times.[1]

One of the most significant challenges facing Guinea worm eradication has been the civil war in southern Sudan, which was largely inaccessible to health workers due to violence.[1][20] To address some of the humanitarian needs in southern Sudan, in 1995, the longest ceasefire in the history of the war was achieved through negotiations by Jimmy Carter.[1][20] Commonly called the “Guinea worm cease-fire,” both warring parties agreed to halt hostilities for nearly six months to allow public health officials to immunize children and begin Guinea worm eradication programming, among other interventions.[20]Hopkins, Donald R.; Withers, P. Craig, Jr., "Sudan's war and eradication of dracunculiasis", The Lancet, 360: s21–s22{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Public health officials cite the formal end of the war in 2005, as a turning point in Guinea worm eradication because it has allowed health care workers greater access to southern Sudan’s endemic areas.[13] One remaining area in West Africa outside of Ghana remains challenging to ending Guinea worm: northern Mali, where Tuareg rebels have made some affected areas unsafe for health workers.

Status of eradication efforts

The World Health Organization is the international body that certifies whether a disease has been eliminated from a country or eradicated from the world. Endemic countries must report to the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication and document the absence of indigenous cases of Guinea worm disease for at least 3 consecutive years to be certified as Guinea worm-free by the World Health Organization.[21]

List of countries that have stopped transmission of Guinea worm or been WHO-certified as having eliminated the disease:[22]

Stopped Transmission in

- Benin - 2004

- Burkina Faso - 2006

- Chad - 1998

- Cote d'lvoire - 2006

- Ethiopia - 2006

- Kenya - 1994

- Mauritania - 2004

- Togo - 2006

- Uganda - 2003

WHO Certified

Guinea worm through history

- The unusually high incidence of dracunculiasis in the city of Medina led to it being included in part of the disease’s scientific name “medinensis.” A similar high incidence along the Guinea coast of West Africa gave the disease its more commonly used name.[2] Guinea worm is no longer endemic in either location.

- The 2nd century B.C., Greek writer Agatharchides, described this affliction as being endemic amongst certain nomads in what is now Sudan and along the Red Sea.[2]

- Guinea worm has been found in calcified Egyptian mummies.[3]

- Many believe certain symbols of medicine—the caduceus and the staff of Asklepios—represent the treatment for Guinea worm disease, as they portray either one or two snakes wrapped around a stick.[23]

- Guinea worm may be the “fiery serpent” that plagued the Israelites in the Old Testament: “And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.” (Numbers 21:4-9).[2]

- However the first that described the dracunculasis and the way to treated was the bulgarian physician Hristo Stambolski, during his exile in Yemen.[24]

His theory was, that the cause was infected water, wich people were drinking.

See also

- Infectious disease in the 20th century

- List of infectious diseases

- Tropical disease

- Neglected disease

- Waterborne diseases

- Eradication of infectious disease

- Parasitism

- Smallpox

- Polio

Notes

- ^ a b c d Barry, Michele (2007-06-21), "The Tail End of Guinea Worm — Global Eradication without a Drug or a Vaccine", New England Journal of Medicine, 356 (25): 2561–2564, retrieved 2008-07-15

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, "Dracunculiasis", Tropical Medicine Central Resource, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The Carter Center, "Guinea Worm Eradication Program", The Carter Center, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ a b c d e U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dracunculiasis, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007-08-15), "Progress Toward Global Eradication of Dracunculiasis January 2005—May 2007", Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report, 56 (32): 813–817, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ BASF, Public Health: Products in Action, ABATE®, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2007-03-27), World moves closer to eradicating ancient worm disease, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ "Dose of Tenacity Wears Down a Horrific Disease", New York Times, 2006-03-26, retrieved 2008-07-15

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|author first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|author last=ignored (help) - ^ a b US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1993-12-31), "Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication", Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report, 42 (RR16): 1–25, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ The Carter Center, Guinea Worm Cases Drop to Fewer Than 10,000, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ The Carter Center, Distribution of 1,385 Indigenous Cases of Dracunculiasis Reported, Jan – May 2008* (PDF), retrieved 2008-07-21

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2007-06-25), Guinea Worm Wrap-UP#173 (PDF), p. 1, retrieved 2008-07-21

- ^ a b c "Dracunculiasis Eradication: The Final Inch", American Journal of Tropical Medicine, 73 (4): 669–675, retrieved 2008-07-15

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|author first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|author last=ignored (help) - ^ The Carter Center, "International Task Force for Disease Eradication - Original Members (1989 - 1992)", retrieved 2008-07-17

- ^ Carter, Jimmy; Lodge, Michelle (2008-03-31), "A Village Woman's Legacy" (PDF), TIME, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ Carter, Carter (2004-05-19), "Remarks of Mr Jimmy Carter, former President of the United States of America, at the World Health Assembly", retrieved 2008-07-17

- ^ The Carter Center, Carter (2008-04-02), "Mali's President Touré, Southern Sudan Program Director Logora Honored With The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Award", retrieved 2008-07-17

- ^ The Carter Center, Carter (2008-04-02), "Jimmy Carter and General Dr. Yakubu Gowon Encourage Nigerian Officials to Control Schistosomiasis, Other Diseases", retrieved 2008-07-17

- ^ a b Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (2006), 2006 Gates Award for Global Health: The Carter Center, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ a b c The Carter Center, Sudan, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000-10-11), "Progress Toward Global Dracunculiasis Eradication, June 2000", Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report, 49: 731–735, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ The Carter Center, "Activities by Country - Guinea Worm Eradication Program", The Carter Center, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ McNeil, Donald (2005-03-08), "Slithery Medical Symbolism: Worm or Snake? One or Two?", New York Times, retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ Христо Стамболски: Автобиография, дневници и спомени. (Autobiography of Hristo Stambolski. Sofia : Dŭržavna pečatnica, 1927-1931)