Pomerania in the Early Middle Ages: Difference between revisions

→Religion: + |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History of Pomerania}}'''Pomerania during the Early Middle Ages''' covers the [[Pomerania#History|History of Pomerania]] from the [[Migration Period]] to the 11th century. |

{{History of Pomerania}}'''Pomerania during the Early Middle Ages''' covers the [[Pomerania#History|History of Pomerania]] from the [[Migration Period]] to the 11th century. |

||

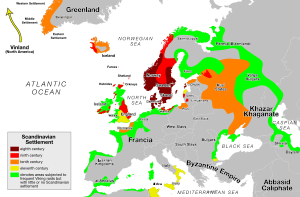

During the second half of the first millenium, [[West Slavs|West Slavic tribes]] settled in [[Pomerania]]. [[Pomeranians (Slavic tribe)|Pomeranian tribes]] settled between [[Oder]] and [[Vistula]] rivers, [[Veleti]] (later "Liuticians") west of the [[Oder]], and [[Rani (Slavic tribe)|Rani]] on the island of [[Rügen]] and the adjacted mainland. [[Viking]] settlements were set up along the coastline for primarily trade and military purposes (e.g. [[Altes Lager Menzlin]] and [[Jomsborg]], respectively). |

During the second half of the first millenium, [[West Slavs|West Slavic tribes]] it's an absurd !!!!!! what evidences you have for such claims???????? the name of the land and the people and many places in that region are of Balts origin!!!!!!! don't put slavs propaganda as a well known fact!!!!!!!!!!!!! settled in [[Pomerania]]. [[Pomeranians (Slavic tribe)|Pomeranian tribes]] settled between [[Oder]] and [[Vistula]] rivers, [[Veleti]] (later "Liuticians") west of the [[Oder]], and [[Rani (Slavic tribe)|Rani]] on the island of [[Rügen]] and the adjacted mainland. [[Viking]] settlements were set up along the coastline for primarily trade and military purposes (e.g. [[Altes Lager Menzlin]] and [[Jomsborg]], respectively). |

||

In the 10th century, the [[Holy Roman Empire]] set up the [[Billung march|Billung]] and [[Northern march]]es west of the Oder, which were divided by the [[Peene]] river. The Liutician federation in an uprising of 983 managed to regain independence, but broke apart in the course of the 11th century due to internal conflicts. In the east, [[Poland|Polish]] [[Piasts]] managed to acquire parts of Pomerania during the late 960s, where the short-lived [[Diocese of Kolberg]] (Kolobrzeg) was installed in 1000 AD. The Pomeranians regained independence during the Pomeranian uprising of 1005. |

In the 10th century, the [[Holy Roman Empire]] set up the [[Billung march|Billung]] and [[Northern march]]es west of the Oder, which were divided by the [[Peene]] river. The Liutician federation in an uprising of 983 managed to regain independence, but broke apart in the course of the 11th century due to internal conflicts. In the east, [[Poland|Polish]] [[Piasts]] managed to acquire parts of Pomerania during the late 960s, where the short-lived [[Diocese of Kolberg]] (Kolobrzeg) was installed in 1000 AD. The Pomeranians regained independence during the Pomeranian uprising of 1005. |

||

Revision as of 16:11, 24 December 2008

| History of Pomerania |

|---|

|

|

|

Pomerania during the Early Middle Ages covers the History of Pomerania from the Migration Period to the 11th century.

During the second half of the first millenium, West Slavic tribes it's an absurd !!!!!! what evidences you have for such claims???????? the name of the land and the people and many places in that region are of Balts origin!!!!!!! don't put slavs propaganda as a well known fact!!!!!!!!!!!!! settled in Pomerania. Pomeranian tribes settled between Oder and Vistula rivers, Veleti (later "Liuticians") west of the Oder, and Rani on the island of Rügen and the adjacted mainland. Viking settlements were set up along the coastline for primarily trade and military purposes (e.g. Altes Lager Menzlin and Jomsborg, respectively).

In the 10th century, the Holy Roman Empire set up the Billung and Northern marches west of the Oder, which were divided by the Peene river. The Liutician federation in an uprising of 983 managed to regain independence, but broke apart in the course of the 11th century due to internal conflicts. In the east, Polish Piasts managed to acquire parts of Pomerania during the late 960s, where the short-lived Diocese of Kolberg (Kolobrzeg) was installed in 1000 AD. The Pomeranians regained independence during the Pomeranian uprising of 1005.

Migration period

The pattern of settlement in Pomerania started to change in the 3rd century. The prospering material cultures of the Roman Iron Age decayed. Only in some areas a continuity of these cultures is observed until the 5th and 6th centuries.[1]

These changes are associated with the Migration period, when Germanic tribes migrated towards the Roman Empire.[1]

Slavic Pomeranians

The 5th century marks the climax of an era that is characterized by a gap between the latest Germanic and the earliest Slavic archaeological findings in Pomerania, that researchers until today cannot explain sufficiently.[1]

Origin debate

There has been a debate concerning the origins of the Slavic tribes in Pomerania.[2] Most German researchers saw the origins of these Slavs east of the Vistula and postulated a westward migration during the 6th and 7th centuries.[2] This hypothesis however lacks a sufficient explaination for the enormous increase in both the inhabited area and the numbers of the settlers.[2] On the other hand, most Polish researchers tried to proof an archeological continuity from the cultures of the Roman Iron Age to the medieval Slavic culture.[2] A third hypothesis is that parts of the Veneti were assimilated by the Germanic tribes, while others became Slavs.[2] Until today, no consensus has been reached by the researchers.[2]

First appearance of Slavic cultures

The first archeological traces of Slavs in Southern Pomerania are ceramics of the Deetz type, found at the lower Oder river, and dated back to the 6th or the beginning 7th century.[3] These findings are associated with a first wave of immigrants coming from what is now Southwestern Poland.[3] Farther Pomerania and Pomerelia seem to have been unsettled in this period, yet archeological research in Pomerelia is still on a low level compared to Farther Pomerania.[3]

Slavic Feldberg type ceramics, found in a region comprising the Oder area and the adjacent eastern areas up to the Persante (Parseta) river, are dated back to the 7th and 8th century.[3] The Feldberg type by some researchers is associated with a second wave of immigrantion from Silesia, Bohemia and Lesser Poland.[3]

Pomerelia has also been settled by Slavs in the 7th and 8th century.[3] Based on archeological and linguistic findings, it has been postulated that these settlers moved northward along the Vistula river.[3] This however contradicts another hypothesis supported by some researchers saying the Veleti moved westward from the Vistula delta.[3]

Slavic settlement reached Western Pomerania in the 9th century, probably already in the eighth.[4]

Tribal and territorial organization

By the 9th to 11th century the region was recorded as inhabited by various tribes belonging to the Lechitic group of the West Slavs, known collectively as Veleti, later Liutizian tribes dwelling west and Pomeranian tribes dwelling east of the Oder river.[5] The Rani lived on the island of Rügen and the adjacted mainland. The tribes spoke Polabian (Veleti, Rani) and closely related Pomeranian (Pomeranians) dialects. A Frankish document entitled Bavarian Geographer (ca 845) mentions the tribes of Volinians[5] (Velunzani), Pyritzans[5] (Prissani), Ukrani (Ukri) and Veleti[5] (Wiltzi) around the lower Oder.[6]

From the 9th to the 11th century, at least ten Pomeranian tribes dwelled between the Oder and Vistula river. They are not known by name except for the Volinians and Pyritzans. It is uncertain if these tribes ever formed a tribal union, or if they were split in western and eastern tribes from the beginning, with the western tribes oriented towards the Veleti.[5]

The settlements of the distinct tribes were separated from each other and from their neighbors by vast woodlands. In 1124, it took Otto of Bamberg three days to cross the woods separating the Pomeranians from the neighboring Poles.[6]

The territorial extension and population density differed significantly between the tribes. The Volinians' tribal area was rather small, but densely populated. The center of the Volinian territory was a town-like settlement located at the site of the modern town of Wolin (Wollin) on Wolin (Wollin) island. Russian, Saxon, and Scandinavian merchants lived in this settlement. The rest of the tribal area was densely populated with about one settlement every foure square kilometers in 1000 AD. In contrast, the Pyritzans's tribal area was larger, comprising the area around Pyritz and Stargard, but the settlement density was only one settlement every twenty square kilometers.[7]

The Veleti tribes in 983 formed the Liutizian federation, comprising the Circipanes, Kessinians, Redarians, and Tollensians, probably also the Hevelli and Rani. The Volinians also played an important role.[8] They were at various times both ally and military target of the Holy Roman Empire and Poland. The federation declined in the 1050s due to internal struggles.[9]

There are sparse records of dukes in this area, but no records about the extension of their duchies or any dynastic relations. The first written record of any local Pomeranian ruler is the 1046 mention of Zemuzil[6][10] (in Polish literature also called Siemomysł) at an imperial meeting. Another chronicle written in 1113 by Gallus Anonymus mentions several dukes of Pomerania: Swantibor, Gniewomir, and an unnamed duke besieged in Kołobrzeg (Kolberg).

Religion

The Middle Ages' Pomeranians, Liutizians and Rani believed in numerous gods of the Slavic mythology.

The gods were worshipped in temples, sacred groves, sacred trees and sacred springs. The priesthood was a powerful class of the society. The elders held their assemblies in the sacred places. Important decisions were made only after asking an oracle.[11]

Important oracles were horse oracles in Stettin and Arkona.

Major temple sites were

- Arkona (Swantewit temple)

- Charenza (numerous temples, e.g. Porenut, Rugievit)

- Gützkow

- Wolgast (Jarovit temple)

- Wollin (worship an idol referred to as "The iron lance of Caesar")[12]

- Stettin (two to four temples,[12] most notably the temple of Triglaw, a three-headed god[12] and a sacred walnut tree[11])

Billung and Northern marches (936-983)

In 936, the area west of the Oder River was incorporated in the March of the Billungs (north of the Peene River) and the Northern March (south of the Peene River) of the Holy Roman Empire. The respective bishoprics were the Diocese of Hamburg-Bremen and Diocese of Magdeburg. In 983, the area regained independence in an uprising initiated by the Liutizian federation.[9] The margraves and bishops upheld their claims, but were not able to reinforce them despite various expeditions.[13]

Polish gains and the Diocese of Kolobrzeg (Kolberg, 1000 - 1005)

The first Polish duke Mieszko I invaded Pomerania and subdued the burgh of Kolberg (Kolobrzeg) and the adjacent areas in the 960s.[14] He also fought the Volinians, but despite a won battle in 967, he did not succeed in expanding his Pomeranian gains.[8] His son and successor Boleslaw I continued to campaign in Pomerania, but also failed to subdue the Volinians and the lower Oder areas.[14]

During the Congress of Gniezno in 1000 AD, Boleslaw created the first, yet short-lived bishopric in Pomerania Diocese of Kolberg, subordinate to the Archdiocese of Gniezno, headed by Saxon bishop Reinbern, which was destroyed when Pomeranians revolted in 1005.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] Of all Liutizians, the Volinians were especially devoted to participation in the wars between the Holy Roman Empire and Poland from 1002 to 1018 to prevent Boleslaw I from reinstating his rule in Pomerania.[10]

Jomsvikings, Scandinavian settlements

Canute the Great was the son of sea-king Sweyn Forkbeard, also reputed to be a member of the Jomsburg Vikings, a military organization of mercenary warriors with a fortress based in Pomerania. There is some dispute among historians, however, over the existence of the "Jomsvikings." Canute's mother was Gunhild (formerly Swiatoslawa, daughter of Mieszko I of Poland). In about 1020, Canute made a deal with Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II, and the emperor gave Canute the Mark of Schleswig and Pomerania to govern. Nevertheless, Pomerania or parts thereof may or may not have been part of that deal. In any event, Boleslaus sent his troops to help Canute in his successful conquest of England.

Other Viking Age Scandinavian settlements at the Pomeranian coast besides Jomsborg (which is believed today to be identical with Vinata, Jumne and Wolin) include Ralswiek (on the isle of Rügen) and Altes Lager Menzlin (at the lower Peene river).[25]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.26, ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b c d e f Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, pp.26,27 ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.29 ISBN 839061848

- ^ Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.21, ISBN 3931185567

- ^ a b c d e Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.30 ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b c Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.22,23, ISBN 3886802728

- ^ Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, pp.30,31, ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.31, ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b Joachim Herrmann, Die Slawen in Deutschland, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985, pp.261,345ff

- ^ a b Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.33, ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.47, ISBN 839061848

- ^ a b c Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.45, ISBN 839061848

- ^ Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.28,29, ISBN 3886802728

- ^ a b Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.32, ISBN 839061848

- ^ Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.32, ISBN 839061848:pagan reaction of 1005

- ^ Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.25, ISBN 3886802728: pagan uprising that also ended the Polish suzerainity in 1005

- ^ Jürgen Petersohn, Der südliche Ostseeraum im kirchlich-politischen Kräftespiel des Reichs, Polens und Dänemarks vom 10. bis 13. Jahrhundert: Mission, Kirchenorganisation, Kultpolitik, Böhlau, 1979, p.43, ISBN 3412045772: 1005/13

- ^ Oskar Eggert, Geschichte Pommerns, Pommerscher Buchversand, 1974: 1005-1009

- ^ Roderich Schmidt, Das historische Pommern: Personen, Orte, Ereignisse, Böhlau, 2007, p.101, ISBN 341227805X: 1005/13

- ^ A. P. Vlasto, Entry of Slavs Christendom, CUP Archive, 1970, p.129, ISBN 0521074592: abandoned 1004 - 1005 in face of violent opposition

- ^ Nora Berend, Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus' C. 900-1200, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p.293, ISBN 0521876168, 9780521876162

- ^ David Warner, Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg, Manchester University Press, 2001, p.358, ISBN 0719049261, 9780719049262

- ^ Michael Borgolte, Benjamin Scheller, Polen und Deutschland vor 1000 Jahren: Die Berliner Tagung über den"akt von Gnesen", Akademie Verlag, 2002, p.282, ISBN 3050037490, 9783050037493

- ^ Michael Müller-Wille, Rom und Byzanz im Norden: Mission und Glaubenswechsel im Ostseeraum während des 8.-14. Jahrhunderts: internationale Fachkonferenz der deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Verbindung mit der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz: Kiel, 18.-25. 9. 1994, 1997, p.105, ISBN 3515074988, 9783515074988

- ^ Joachim Herrmann, Die Slawen in Deutschland, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985, pp.pp.237ff,244ff