Qin Shi Huang: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 71.103.179.215 to last revision by ClueBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

===Economy=== |

===Economy=== |

||

Qin Shi Huang and [[Li Si]] unified China economically by |

Qin Shi Huang and [[Li Si]] unified China economically by standardizing the [[Chinese units of measurement]]s such as weights and [[Units of measurement|measures]], the [[currency]], the length of the [[axle]]s of [[cart]]s to facilitate transport on the road system.<ref name="Veeck" /> The emperor also developed an extensive network of roads and canals connecting the provinces to improve trade between them.<ref name="Veeck" /> The currency of the different states were also standardized to the [[Banliang|Ban liang coin]] (半兩).<ref name="Chang" /> Perhaps most importantly, the [[Chinese character|Chinese script]] was unified. Under Li Si, the [[seal script]] of the state of Qin was standardized through removal of variant forms within the Qin script itself. This newly standardized script was then made official throughout all the conquered regions, thus doing away with all the regional scripts to form one language, one communication system for all of China.<ref name="Chang" /> |

||

===Identification=== |

===Identification=== |

||

Revision as of 02:59, 11 February 2009

| Qin Shi Huang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reign | July 246 BCE–221 BCE |

| Reign | 221 BCE–, 210 BCE |

Qin Shi Huang (Chinese: 秦始皇; pinyin: Qín Shǐhuáng; Wade–Giles: Ch'in Shih-huang) (259 BCE – 210 BCE),[1][2] personal name Ying Zheng (Chinese: 嬴政; pinyin: Yíng Zhèng), was king of the Chinese State of Qin from 246 BCE to 221 BCE during the Warring States Period.[3] He became the first emperor of a unified China in 221 BCE.[3] He ruled until his death in 210 BCE at the age of 50.[4]

Qin Shi Huangdi remains a controversial figure in Chinese history. After unifying China, he and his chief adviser Li Si passed a series of major economical and political reforms.[3] He undertook gigantic projects, including the first version of the current Great Wall of China, the now famous city-sized mausoleum guarded by a life-sized Terracotta Army, and a massive national road system, all at the expense of many lives. To ensure stability, Qin Shi Huang outlawed Confucianism and buried alive many scholars.[4] All books other than those officially decreed were banned and burned. Despite the tyranny of his autocratic rule, Qin Shi Huang is regarded as a pivotal figure.

Name

Shǐ Huángdì

"First Emperor"

(small seal script

from 220 BCE)

Title meaning

After conquering the last independent Chinese state in 221 BCE as the king over all of China. He created a new title calling himself the First Emperor (Chinese: 始皇帝; pinyin: Shǐ Huáng Dì; Wade–Giles: Shih Huang-Ti), shortened as (皇帝).

- The character (始) - means first.[5] The first emperor's heirs would then be successively called "Second Emperor", "Third Emperor" and so on down the generations.[6]

- The characters (皇帝) - Comes from the previous mythical Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors (三皇五帝), where the two characters (皇帝) are extracted.[7] By adding such a title, he hoped to appropriate some of the previous Yellow Emperor's (黃帝) divine status and prestige.[8]

Usage

Both the name Qin Shi Huangdi (秦始皇帝) and Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) appears in the Records of the Grand Historian written by Sima Qian. The longer name Qin Shi Huangdi (秦始皇帝) appear first in chapter 5.[9] Though the shorter name Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) was the name of Chapter 6 (秦始皇本紀).[10][11]

Youth

Birth

A rich merchant in the state of Han named Lü Buwei met Master Yiren (公子異人). Lü Buwei's manipulation helped Yiren become King Zhuangxiang of Qin.[4] At the time, King Zhuangxiang of Qin was a prince of blood Qin, who took residence in the court of Zhao as hostage to guarantee armistice between the two states.[12]

According to the Records of the Grand Historian Ying Zheng, first emperor, was born in 259 BCE as the eldest son of King Zhuangxiang of Qin.[2][13] King Zhaoxiang of Qin saw a concubine belonging to Lü Buwei, and she bore the first emperor.[13] At first birth he was given the personal name Zheng (政).[13] Because Zheng was born in Handan, capital of the enemy state of Zhao (趙), he had the name Zhao Zheng.[13] Ying Zheng's ancestors are said to have come from Gansu province.[2]

Birth controversy

The first emperor may not have been the actual son of King Zhaoxiang of Qin. By the time Lü Buwei introduced the woman Zhao Ji (趙姬) to King Zhuangxiang of Qin, she was already pregnant.[12] According to translated texts of Annals of Lü Buwei the woman bore the emperor in Handan 259 BCE in the first month of the 48th year of King Zhaoxiang of Qin.[14] There was some inconsistency between the date of birth and the theory that Lü Buwei was the real father of the first emperor.[14] In the view of some scholars, the length of the pregnancy was irregular, lasting a full year, impossible according to modern medicine.[14] Though some scholars believe the passage inserted into the Grand Records about him being Lü Buwei's son added to the negative image of the emperor, which persisted for over 2,000 years.[5] Because of this, there is a great deal of controversy regarding the first emperor's identity. Different sources have pointed to the different theories.

King of Qin state

Teenage years

In 246 BCE, when King Zhuangxiang of Qin died after a short term of just 3 years, he was succeeded to the throne by his 13 year old son.[15] At the time Ying Zheng was still young, Lü Buwei acted as the regent prime minister of Qin state, which was still waging war against the neighboring seven states.[16]

Lao Ai's attempted coup

As King Zheng grew older, Lü Buwei became fearful that the boy king would discover his liaison with his mother Zhao Ji (趙姬). He decided to distance himself and look for a king replacement. He found a man named Lao Ai (嫪毐), who had a reputation of having a large penis.[17] The Record of Grand historian said Lao Ai was disguised as a eunuch by plucking his beard. Later Lao Ai and queen Zhao Ji got along so well they secretly had two sons together.[17] Lao Ai then became ennobled as Marquis Lao Ai, and was showered with riches. Lü Buwei's plot was supposed to replace King Zheng with one of the hidden sons. But during a dinner party drunken Lao Ai was heard bragging about being the young king's step father.[17] In 238 BCE the king was traveling away to the ancient capital of Yong (雍). Lao Ai seized the queen mother's Chinese seal and mobilized an army in an attempt to start a coup and rebel.[17]

A price of 1 million copper coins were already placed on Lao Ai's head if he was taken alive or half a million if dead.[17] Lao Ai's supporters were captured and beheaded.[17] Lao Ai was tied up and torn to two pieces by horse carriages, while his entire family was executed to the third degree.[17] The two hidden sons were also killed, while mother Zhao Ji was placed under house arrest until her death many years later. Lü Buwei drank a cup of poison wine and committed suicide in 235 BCE.[17][16] Ying Zheng then assumed full power as the King of Qin state. Replacing Lü Buwei, Li Si was also now the new chancellor.

Jing Ke's assassination mission

King Zheng and his troops continued to take over different states. The state of Yan was small, weak and frequently harassed by soldiers. It was no match for Qin state.[18] So Crown Prince Dan of Yan plotted an assassination attempt to get rid of King Zheng, begging Jing Ke to go on the mission in 227 BCE.[18][4] Jing Ke was accompanied by Qin Wuyang in the plot. Each were supposed to present two gifts to King Zheng, a map of Dukang and the decapitated head of Fan Yuqi.[18]

Qin Wuyang first tried to present the map case gift, but was soon trembling in fear. He did not move any further. Jing Ke continued to advance toward the king, while explaining his partner "has never set eyes on the Son of Heaven", which is why he is trembling. Jing Ke had to present both gifts by himself.[18] While unrolling the map, a dagger was revealed. The king drew back, stood on his feet, but struggled to draw the sword to defend himself.[18] At the time other palace officials were not allowed to carry weapons. Jing Ke continued to pursue the king, he took a stab and missed. King Zheng then drew out his sword and cut Jing Ke's thigh. Jing Ke then threw the dagger, but missed again. Jing Ke, suffering 8 wounds from the king's sword, realised his attempt had failed. Both he and Qin Wuyang would be killed afterwards.[18] Yan state would then be conquered by Qin state 5 years later.[18]

Gao Jianli's assassination mission

Gao Jianli was a close friend of Jing Ke, who tried to avenge his death.[19] As a famous lute player, one day he was summoned by King Zheng to play the instrument. Someone in the palace who had known him in the past exclaimed, "This is Gao Jianli".[20] The emperor, unable to bring himself to kill such a skilled musician, ordered his eyes put out.[20] But the king allowed Gao Jianli to play in his presence.[20] He praised the playing and even allowed Gao Jianli to get closer. As part of the plot, the lute was fastened with a heavy piece of lead. He raised the lute and struck at the king. He missed and his assassination attempt failed. Gao Jianli was later executed.[20]

First unification of China

In 230 BCE, King Zheng unleashed the final campaign of the Warring States Period. The state of Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan were already occupied by Qin.[21] One notable natural disaster was the 229 BCE Zhao state earthquake, which Qin state took advantage of to invade the Zhao territory.[22][23] By 221 BCE Qin state defeated the last independent state of Qi. He had completed his quest by annihilating all Chinese states to create one. In that same year, king Zheng proclaimed himself the "First Emperor" (始皇帝).[21] In the South region, the military expansion continued during his reign, annexing regions to what is now Guangdong province and part of today's Vietnam.[23]

First Emperor of Qin dynasty

Division and politics

In an attempt to avoid a recurrence of the political chaos of the Warring States Period, Qin Shi Huang and his prime minister Li Si completely abolished feudalism.[23] He abolished the use of states (國).[24] This prevented the previously conquered states to be referred to as independent nations or states. The empire was then divided into 36 commanderies (郡). It was later increased to more than 40 commanderies.[23] The whole of China now divided into administrative units of commendary, then districts (縣), counties (鄉) and hundred-family units (里).[24] This system was different from the previous dynasties, which had loose alliances and federations before.[25] People could no longer be identified by their native region of former feudal state. For example a person from Chu was called Chu people (楚人) before.[24][26] The administration was now based on merit instead of hereditary rights.[24]

Economy

Qin Shi Huang and Li Si unified China economically by standardizing the Chinese units of measurements such as weights and measures, the currency, the length of the axles of carts to facilitate transport on the road system.[25] The emperor also developed an extensive network of roads and canals connecting the provinces to improve trade between them.[25] The currency of the different states were also standardized to the Ban liang coin (半兩).[24] Perhaps most importantly, the Chinese script was unified. Under Li Si, the seal script of the state of Qin was standardized through removal of variant forms within the Qin script itself. This newly standardized script was then made official throughout all the conquered regions, thus doing away with all the regional scripts to form one language, one communication system for all of China.[24]

Identification

Qin Shi Huang also followed the school of the five elements, earth, wood, metal, fire and water. It was believed that the royal house of the previous dynasty Zhou had ruled by the power of fire, which was the color red. Thus the new Qin dynasty must be ruled by the next element on the list, which is water, presented by the color black. Thus black became the colour for garments, flags, pennants.[27] Other associations include north as the cardinal direction, winter season and the number six.[28] Tallies and official hats were six inches long, carriages six feet wide, one pace (步) was 6 feet.[27]

Zhang Liang's assassination mission

In 230 BCE Qin state had defeated Han state. Coming from an aristocratic Han family Zhang Liang sold all the valuables he had to make way for revenge. He hired a strongman assassin and built him a heavy metal cone weighting 120 jin.[17] The two men hid among the mountain bushes along the emperor's route. At a signal the muscular assassin hurled the cone at the carriage and shattered it. However the emperor was actually in the second carriage as he was traveling with two identical carriages. The assassin ambushed the wrong carriage and the attempt failed in 218 BCE.[21] Both men were able to escape.[17]

North: Great wall

The Qin fought nomadic tribes to the north and northwest. The Xiongnu tribes were subdued, but the campaign was essentially inconclusive, and to prevent the Xiongnu from encroaching on the northern frontier any longer, the emperor ordered the construction of an immense defensive wall.[23][29] This wall, for whose construction hundreds of thousands of men were mobilized, and an unknown number died, is a precursor to the current Great Wall of China. Very little survives today of the great wall built by the first emperor as the original wall sections went to ruins centuries ago.[30]

South: Ling canal

A famous South China quote once famously said "North have the Great wall, South have the Ling canal" (北有長城、南有靈渠).[31] In 214 BCE the Emperor began the project of a major canal to transport supplies to the army.[32] The canal allow water transport between north and south China.[32] The 34 km canal links the xiang river which flows into the Yangtze and the Li Jiang, which flows into the Pearl river.[32] The canal connected two of China's major waterways and aided Qin's expansion to the southwest territory.[32] The construction is considered one of the three great feats of Chinese engineering, the others being the Great Wall and the Sichuan Dujiangyan Irrigation System.[32]

End of hundred schools of thought

While the previous Warring States era was war torn between the states, it was also considered the golden age of free thoughts.[33] Qin Shi Huang eliminated the Hundred Schools of Thought which incorporated Confucianism and other philosophies.[33][34] After the unification of China, with all other schools of thought banned, legalism became the endorsed ideology of the Qin dynasty.[24] Legalism was basically a system that require the people to follow the laws or be punished accordingly.

Book burning period

Beginning in 213 BCE Qin Shi Huang also ordered most previously existing books burned, where written records not related to his former Qin state were burnt.[35] Owning the Book of songs and Book of history as well as texts of the hundred schools handed down severe punishments. In the following year some 460 scholars were buried alive.[35] Some medical and agricultural texts held in the palace archives.[36] The emperor's oldest son Fusu criticised him for this act.[37]

Other achievements

After the unification, Qin Shi Huang moved out of Xianyang palace (咸陽宮), and began building the gigantic Epang palace (阿房宫) south of Wei river.[38] Other achievements such as the 12 bronze colossi were also made from the collected weapons.

Death and aftermath

Elixir of life

Later in his life, Qin Shi Huang feared death and desperately sought the fabled elixir of life, which supposedly allow him to live forever. He was obsessed with acquiring immortality and fell prey to many who offered him supposedly elixirs.[39] He visited Zhifu Island three times in order to achieve this end.[40] In one case he sent Xu Fu, a Zhifu islander, with ships carrying hundreds of young men and women in search of the mystical Penglai mountain.[21] These people never returned, because they knew that if they returned without the promised elixir, they would surely be executed. Legends claim that they reached Japan and colonized it.[39]

Death

In 211 BCE a large meteor stone is said to have fallen in Dongjun (東郡) at the lower reach of the Yellow river. On it an unknown person inscribed the words "The First Emperor will die and his land will be divided."[41] When the emperor heard of this, he sent an imperial secretary to investigate this prophecy. No one would confess to the deed and all people living in the vicinity of the stone was put to death. The stone was then burned and pulverized.[13]

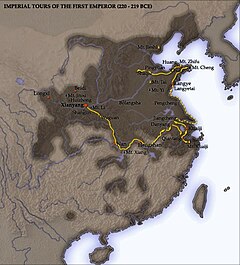

The emperor did die while on one of his tours of Eastern China, on September 10, 210 BCE (Julian Calendar) at the palace in Shaqiu prefecture (沙丘平台), about two months away by road from the capital Xianyang.[42][18][43][18] Reportedly, he died of swallowing mercury (poison) pills, made by his court scientists and doctors, which contained too much mercury.[44] Ironically, these pills were meant to make Qin Shi Huang immortal.[44]

After the emperor's death Prime Minister Li Si, who accompanied him, was extremely worried that the news of his death could trigger a general uprising in the empire.[18] It would take two months for the government to reach the capital, and it would not be possible to stop the uprising. Li Si decided to hide the death of the emperor, and return to Xianyang.[18] Most of the imperial entourage accompanying the emperor was left uninformed of the emperor's death, only son Ying Huhai, eunuch Zhao Gao and five or six favorite eunuchs knew of the death.[18] Li Si also ordered that two carts containing rotten fish be carried immediately before and after the wagon of the emperor.[18] The idea behind this was to prevent people from noticing the foul smell emanating from the wagon of the emperor, where his body was starting to decompose severely.[18]

Second emperor conspiracy

Eventually, after about two months, Li Si and the imperial court were back in Xianyang, where the news of the death of the emperor was announced.[18] Qin Shi Huang did not like to talk about death and he never really wrote a will. After his death, the eldest son Fusu was supposed to be the next emperor.[45]

Li Si and the chief eunuch Zhao Gao conspired to kill Fusu. The reason being, Fusu's favorite general was Meng Tian, whom they disliked.[45] They were afraid that if Fusu was enthroned, they would lose their power.[45] So Li Si and Zhao Gao forged a fake letter from Qin Shi Huang saying that both Fusu and General Meng must commit suicide.[45] The plan worked, and the younger son Huhai became the Second Emperor later known as Qin Er Shi.[18]

Qin Er Shi, however, was not as capable as his father. Revolts against him quickly erupted. His reign was a time of extreme civil unrest, and everything that worked for the First Emperor had crumbled away within a short period.[23] One of the immediate revolt attempts was the 209 BCE Chen Sheng Wu Guang Uprising led by Chen She and Wu Guang.[41]

Legacy

Mausoleum of the First emperor

The Chinese historian Sima Qian, writing a century after the First emperor's death, wrote that it took 700,000 men to construct it. The British historian John Man points out that this figure is larger than any city of the world at that time and calculates that the foundations could have been built by 16,000 men in two years.[46] While Sima Qian never mentioned the terracotta army, the statues were discovered by a team of well diggers in 1974.[47] The soldiers were created with a series of mix-and-match clay molds and then further individualized by the artists' hand.

Qin Shi Huang tomb

One of the first projects the young king accomplished while he was alive was the construction of his own tomb. In 215 BCE Qin Shi Huang ordered General Meng Tian with 300,000 men to begin construction.[36] Other sources suggested he ordered 720,000 non-paid laborers to build his tomb to specification.[15] The main tomb (located at 34°22′52.75″N 109°15′13.06″E / 34.3813194°N 109.2536278°E) containing the emperor has yet to be opened and there is evidence suggesting that it remains relatively intact.[48] Sima Qian's description of the tomb includes replicas of palaces and scenic towers, 'rare utensils and wonderful objects', 100 rivers made with mercury, representations of 'the heavenly bodies', and crossbows rigged to shoot anyone who tried to break in.[49] The tomb was built on Li Mountain which is only 30 kilometers away from Xi'an.[50] Modern archaeologists have located the tomb, and have inserted probes deep into it. The probes revealed abnormally high quantities of mercury, some 100 times the naturally occurring rate, suggesting at least part of the legend can be trusted.[44] Secrets were maintained, as most of the workmen who built the tomb were killed.[51][44]

Family of Qin Shi Huang

The following are some family members in relation to Qin Shi Huang:

- Great great grandfather Huiwen of Qin (秦惠文王)

- Great grandfather Zhaoxiang of Qin (秦昭襄王)

- Grandfather Xiaowen of Qin (秦孝文王)

- Father King Zhuangxiang of Qin (秦庄襄王)

- Mother Zhao Ji (趙姬)

- Brother: Changan jun (長安君成蟜)[10]

- Qin shi huang himself

- Son: Fusu

- Son: Qin Er Shi

Historiography of Qin Shi Huang

In traditional Chinese historiography, the First Emperor of the Chinese unified states was almost always portrayed as a brutal tyrant who had obsessive fear of assassination. Ideological prejudices against the Legalist State of Qin were established as early as 266 BCE, when Confucian philosopher Xun Zi disparaged it. Later Confucian historians condemned the emperor who had burned the classics and buried Confucian scholars alive. They eventually compiled a list of the Ten Crimes of Qin to highlight his tyrannical actions.

The famous Han poet and statesman Jia Yi concluded his essay The Faults of Qin (過秦論), with what was to become the standard Confucian judgment of the reasons for Qin's collapse. Jia Yi's essay, admired as a masterpiece of rhetoric and reasoning, was copied into two great Han histories and has had a far-reaching influence on Chinese political thought as a classic illustration of Confucian theory.[52] He explained that the Qin disintegrated because it failed to display humanity and righteousness or to realise there is a difference between the power to attack and the power to consolidate.[53]

Only in modern times were historians able to penetrate beyond the limitations of traditional Chinese historiography. The political rejection of the Confucian tradition as an impediment to China's entry into the modern world opened the way for changing perspectives to emerge.

In the time when he was writing, when Chinese territory was encroached upon by foreign nations, leading Kuomintang historian Xiao Yishan emphasized the role of Qin Shi Huang in repulsing the northern barbarians, particularly in the construction of the Great Wall.

Another historian, Ma Feibai (馬非百), published in 1941 a full-length revisionist biography of the First Emperor entitled Qin Shi Huangdi Zhuan (秦始皇帝傳), calling him "one of the great heroes of Chinese history". Ma compared him with the contemporary leader Chiang Kai-shek and saw many parallels in the careers and policies of the two men, both of whom he admired. Chiang's Northern Expedition of the late 1920s, which directly preceded the new Nationalist government at Nanjing was compared to the unification brought about by Qin Shi Huang.

With the coming of the Communist Revolution in 1949, new interpretations again surfaced. The establishment of the new, revolutionary regime meant another re-evaluation of the First Emperor, this time following Marxist theory. The new interpretation given of Qin Shi Huang was generally a combination of traditional and modern views, but essentially critical. This is exemplified in the Complete History of China, which was compiled in September 1955 as an official survey of Chinese history. The work described the First Emperor's major steps toward unification and standardisation as corresponding to the interests of the ruling group and the merchant class, not the nation or the people, and the subsequent fall of his dynasty as a manifestation of the class struggle. The perennial debate about the fall of the Qin Dynasty was also explained in Marxist terms, the peasant rebellions being a revolt against oppression — a revolt which undermined the dynasty, but which was bound to fail because of a compromise with "landlord class elements".

Since 1972, however, a radically different official view of Qin Shi Huang has been given prominence throughout China. The re-evaluation movement was launched by Hong Shidi's biography Qin Shi Huang. The work was published by the state press as a mass popular history, and it sold 1.85 million copies within two years. In the new era, Qin Shi Huang was seen as a farsighted ruler who destroyed the forces of division and established the first unified, centralized state in Chinese history by rejecting the past. Personal attributes, such as his quest for immortality, so emphasized in traditional historiography, were scarcely mentioned. The new evaluations described how, in his time (an era of great political and social change), he had no compunctions against using violent methods to crush counter-revolutionaries, such as the "industrial and commercial slave owner" chancellor Lü Buwei. Unfortunately, he was not as thorough as he should have been and after his death, hidden subversives, under the leadership of the chief eunuch Zhao Gao, seized power and used it to restore the old feudal order.

To round out this re-evaluation, a new interpretation of the precipitous collapse of the Qin Dynasty was put forward in an article entitled "On the Class Struggle During the Period Between Qin and Han" by Luo Siding, in a 1974 issue of Red Flag, to replace the old explanation. The new theory claimed that the cause of the fall of Qin lay in the lack of thoroughness of Qin Shi Huang's "dictatorship over the reactionaries, even to the extent of permitting them to worm their way into organs of political authority and usurp important posts."

Qin Shi Huang was ranked #17 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.[54]

Mao Zedong, chairman of the People's Republic of China, was reviled for his persecution of intellectuals. Being compared to the First Emperor, Mao responded: "He buried 460 scholars alive; we have buried forty-six thousand scholars alive... You [intellectuals] revile us for being Qin Shi Huangs. You are wrong. We have surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold."[55]

Qin Shi Huang in fiction

- During the Korean War, the play Song of the Yi River was produced. The play was based on the attempted assassination of the king by Jing Ke. In the play Ying Zheng was portrayed as a cruel tyrant and an aggressor and invader of other states. Jing Ke, in contrast, was a chivalrous warrior who said that "tens of thousands of injured people are all my comrades." A huge newspaper ad for this play proclaimed: "Invasion will definitely end in defeat; peace must be won at a price." The play portrayed an underdog fighting against a cruel, powerful foreign invader with help from a sympathetic foreign volunteer.

- Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986), the Argentine writer, wrote an acclaimed essay on Qin Shi Huang, The Wall and the Books (La muralla y los libros) in the 1952 collection Other Inquisitions (Otras Inquisiciones). It muses on the opposition between large-scale construction of the Great Wall and destruction book-burning that defined his reign.[56]

- The 1956 book Lord of the East is a historical romance about the favourite daughter of Qin Shihuang, who runs away with her lover. The story uses Qin Shihuang to create the barrier for the young couple.[57]

- The 1984 book Bridge of Birds (by Barry Hughart) portrays the emperor as a power-hungry megalomaniac who achieved immortality by having his heart removed by an "Old Man of the mountain."

- The Chinese Emperor, by Jean Levi, appeared in 1984. This work of historical fiction moves from discussions of politics and law in the Qin state to fantasy, in which the First Emperor's terracotta army were actually robots created to replace fallible humans.

- In the Area 51 book series, Qin Shi Huang is revealed to be an alien exile stranded on Earth during an interstellar civil war. The Great Wall is actually designed to display the symbol for 'help' in his language, and he orders it built in the hope that a passing spaceship would notice it and rescue him.

- In Hydra's Ring, the 39th novel in the Outlanders series, Shi Huang Di is revealed to be still alive in the early 23rd century through extraterrestrial nano-technology that has bestowed a form of immortality.

- In the Magic Tree House book series, one book is titled "Day of the Dragon King." The Dragon King is Qin Shi Huangdi.

- Ten Dragon Tails by Candy Taylor Tutt contains "The Wall", a historical fiction short story based on the building of the Great Wall.

- "Emperor!: A Romance of Ancient China" by Lanny Fields centers around Qin Shi Huangdi and a former Roman soldier named Marcus Lucius Scipio, whom Qin Shi Huangdi befriends after Marcus Scipio saves his life on multiple occasions. This fictional account is told through the eyes of the historian Sima Qian, who writes about Marcus Scipio after he travels from Rome to China.

Film and television

- The 1963 Japanese movie Shin No Shikoutei portrays Qin Shi Huang as a battle-hardened emperor with his roots in the military. Despite his rank, he is shown lounging around a campfire with common men. A female character, Lady Chu, serves as a foil who questions whether the emperor's cause is just. He converts her from an enemy to a loyal concubine.[58]

- The 1985 Hong Kong Asia Television Limited (ATV) channel drama series called "The Rise of the Great Wall - Emperor Qin Shi Huang" (秦始皇) was one of ATV's most expensive projects with 63 episodes chronicling Qin Shi Huang's life from his birth to his death. The title song summed up most of the storyline: "The land shall be under my foot; nobody shall be equal to me."[59]

- The 1996 movie The Emperor's Shadow uses legends about Qin Shi Huang to focus on his relationship with the rebellious musician Gao Jianli, known historically as a friend of the would-be assassin Jing Ke. Gao plays a song for the assassin before he sets out to kill the emperor.[60]

- The 1999 movie The Emperor and the Assassin focuses on the identity of the emperor's father, his supposed heartless treatment of his officials, and a betrayal by his childhood lover, paving the way for Jing Ke's assassination attempt. The director of the film, Chen Kaige, sought to question whether the emperor's motives were meritorious. A major theme in this movie is the conflict between the Emperor's dedication to his vows and to his lover, Lady Zhao.[61]

- In the animated series Histeria, Pepper Mills wanted Shi Huang Di's autograph, thinking he was Scooby Doo.

- The 2001 Hong Kong TVB serial drama A Step into the Past, based on a book with the same title, stars Raymond Lam Fung as Zhao Pan, a man from the Kingdom of Zhao who takes over the identity of the emperor and rises to power. He is unwittingly helped by Hong Siu Lung, a time traveller from the 21st century.[62]

- The 2002 Mainland China CCTV serial drama Qin Shi Huang, stars Zhang Fengyi as Qin Shi Huang. It features the fictionalised story of the emperor, from his childhood to his death.[63]

- The 2002 movie Hero, starring Jet Li, tells the story of assassination attempts on Qin Shi Huang (played by renowned Chinese actor Chen Daoming) by legendary warriors. It portrays him as a powerful ruler willing to take any steps to bring unification to his people.

- In The Myth (2005), Jackie Chan plays both a modern-day archaeologist and a general under Qin Shi Huang. Kim Hee-sun starred alongside Jackie Chan as a Korean Princess who was forced to marry Qin Shi Huang.[64]

- Bob Bainborough portrayed Qin Shi Huang in an episode of History Bites.

- In the animated Martin Mystery series, the hero finds that the Terracotta Army was actually created to keep the First Emperor inside his tomb and not to help him in the spiritual world.

- In My Date With A Vampire series 2, a flashback shows that Qin Shi Huang was the Emperor who was deceived into believing that to find immortality was to turn into a vampire.

- In 2006 The Discovery Channel ran a drama-documentary special on Qin Shi Huang called First Emperor: The Man Who Made China, featuring James Pax as the emperor. It was shown on the UK Channel 4 in 2006.

- In 2006 "National Geographic" made a documentary called "Secrets of China's First Emperor, Tyrant and Visionary" an in depth look at the magnificent and controversial ruler.[65]

- In 2006 The History Channel made a special 3 hour documentary called "China's First Emperor" in which Qin Shi Huang was played by Xu Peng Kai.[66]

- In the 2008 film The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor the tomb is unearthed and he is the villious ressurected mummy in this film. However he is highly fictionalised here, incorrectly called the "Han Emperor", having the power to control fire, and turn into a dragon.

Music

- Emperor Qin is the protagonist in the opera The First Emperor by Tan Dun and has been sung by Plácido Domingo on its world premiere.

Video games

- The 1995 computer game Qin: Tomb of the Middle Kingdom depicts a fictional archaeological mission to explore the First Emperor's burial site. The emperor is featured in several voiceovers in Mandarin Chinese.

- The 2003 video game Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb portrays Indiana Jones entering the tomb of Qin Shi Huang to recover "The Heart of the Dragon".

- In the 2002 computer game Prince Of Qin, the user plays Qin Shi Huang's first son Fusu, who was forced to commit suicide. But in this game, Fusu does not die, he will fight for his birth right to inherit the throne and seek the truth of Qin Shi Huang's death.

- In the 2005 computer game Civilization IV, Qin Shi Huang is one of the two playable leaders of China.[68]

- In the computer game Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom, the Qin Dynasty campaign has the player as the head architect of Qin Shi Huang, in charge of overseeing the construction of the capital, the great wall, as well as his tomb and the terracotta army, although the game takes liberties with the timeframes in which these events actually took place.

- The Playstation title Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix deals heavily with the myths of the emperor's tomb, and The Eight Immortals.

References

- ^ "Emperor Qin Shi Huang -- First Emperor of China". TravelChinaGuide.com. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ a b c Wood, Frances Wood. [2008] (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0312381123, 9780312381127. p 2.

- ^ a b c Duiker, William J. Spielvogel, Jackson J. Edition: 5, illustrated. [2006] (2006). World History: Volume I: To 1800. Thomson Higher Education publishing. ISBN 0495050539, 9780495050537. pg 78.

- ^ a b c d Ren, Changhong Ren. Wu, Jingyu. [2000] (2000). Rise and Fall of Qin Dynasty. Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. ISBN 9812291725, 9789812291721.

- ^ a b Wood, Frances Wood. [2008] (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0312381123, 9780312381127. p 26. Cite error: The named reference "Wood2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hardy, Grant. Kinney, Anne Behnke. [2005] (2005). The Establishment of the Han Empire and Imperial China. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 031332588X, 9780313325885. p 10.

- ^ The Great Wall. [1981] (1981). Luo, Zhewen Luo. Lo, Che-wen. Wilson, Dick Wilson. Drege, J. P. Contributor Che-wen Lo. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070707456, 9780070707450. pg 23.

- ^ Fowler, Jeaneane D. [2005] (2005). An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1845190866, 9781845190866. pg 132.

- ^ Wikisource Records of the Grand Historian Chapter 5

- ^ a b Wikisource Records of the Grand Historian Chapter 6

- ^ Book.sina.com.cn. "Sina." 帝王相貌引起的歷史爭議. Retrieved on 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Huang, Ray. China: A Macro History Edition: 2, revised. [1987] (1987). M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1563247305, 9781563247309. pg 32.

- ^ a b c d e Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty in English translated. [1996] (1996). Ssu-Ma, Ch'ien. Sima, Qian. Burton Watson as translator. Edition: 3, reissue, revised. Columbia. University Press. ISBN 0231081693, 9780231081696. pg 35. pg 59.

- ^ a b c Lü, Buwei. Translated by Knoblock, John. Riegel, Jeffrey. The Annals of Lü Buwei: Lü Shi Chun Qiu : a Complete Translation and Study. [2000] (2000). Stanford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0804733546, 9780804733540.

- ^ a b Donn, Lin. Donn, Don. Ancient China. [2003] (2003). Social Studies School Service. Social Studies. ISBN 1560041633, 9781560041634. pg 49.

- ^ a b Wood, Frances Wood. [2008] (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0312381123, 9780312381127. p 24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mah, Adeline Yen. [2003] (2003). A Thousand Pieces of Gold: Growing Up Through China's Proverbs. Published by HarperCollins. ISBN 0060006412, 9780060006419. p 32-34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Sima Qian. Dawson, Raymond Stanley. Brashier, K. E. [2007] (2007). The First Emperor: Selections from the Historical Records. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199226342, 9780199226344. pg 15 - 20, pg 82, pg 99.

- ^ Elizabeth, Jean. Ward, Laureate. [2008] (2008). The Songs and Ballads of Li He Changji. ISBN 1435718674, 9781435718678. p 51

- ^ a b c d Wu, Hung. The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art. Stanford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0804715297, 9780804715294. p 326.

- ^ a b c d Wintle, Justin Wintle. [2002] (2002). China. Rough Guides publishing. ISBN 1858287642, 9781858287645. p 61. p 71.

- ^ Hk.chiculture.net. "HKChinese culture." 破趙逼燕. Retrieved on 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Haw, Stephen G. [2007] (2007). Beijing a Concise History. Routledge. ISBN 978041539906-7. p 22 -23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chang, Chun-shu Chang. [2007] (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, CA. 1600BC - 8AD. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472115332, 9780472115334. p 43-44.

- ^ a b c Veeck, Gregory. Pannell, Clifton W. [2007] (2007). China's Geography: Globalization and the Dynamics of Political, Economic, and Social Change. Rowman & Littlefield publishing. ISBN 0742554023, 9780742554023. p57-58.

- ^ The source also mention ch'ien-shou was the new name of the Qin people. Maybe wade giles romanization is (秦受) "subjects of the Qin empire"?

- ^ a b Wood, Frances Wood. [2008] (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0312381123, 9780312381127. p 27.

- ^ Murowchick, Robert E. [1994] (1994). China: Ancient Culture, Modern Land. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. ISBN 0806126833, 9780806126838. p105.

- ^ Li, Xiaobing. [2007] (2007). A History of the Modern Chinese Army. University Press of Kentucky, 2007.ISBN 0813124387, 9780813124384. p.16

- ^ Huang, Ray. [1997] (1997). China: A Macro History. Edition: 2, revised, illustrated. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1563247313, 9781563247316. p 44

- ^ Sina.com. "Sina.com." 秦代三大水利工程之一:灵渠. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ a b c d e Mayhew, Bradley. Miller, Korina. English, Alex. South-West China: lively Yunnan and its exotic neighbours. Lonely Planet. ISBN 186450370X, 9781864503708. pg 222.

- ^ a b Goldman, Merle. [1981] (1981). China's Intellectuals: Advise and Dissent. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674119703, 9780674119703. pg 85.

- ^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam. [2004] (2004). History of Modern China. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 8126903155, 9788126903153. pg 317.

- ^ a b Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee. Ames, Roger T. [2006] (2006). Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation. SUNY Press. ISBN 079146749X, 9780791467497. p 25.

- ^ a b Wood, Frances Wood. [2008] (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0312381123, 9780312381127. p 33.

- ^ Twitchett, Denis. Fairbank, John King. Loewe, Michael. The Cambridge History of China: The Ch'in and Han Empires 221 B.C.-A.D. 220. Edition: 3. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0521243270, 9780521243278. p 71.

- ^ Chang, Kwang-chih. Xu, Pingfang. Lu, Liancheng. Allan, Sarah. [2005] (2005). The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300093829, 9780300093827. pg 258.

- ^ a b Ong, Siew Chey. Marshall Cavendish. [2006] (2006). China Condensed: 5000 Years of History & Culture. ISBN 9812610677, 9789812610676. p 17.

- ^ Aikman, David. [2005] (2005). Qi. Publishing Group. ISBN 0805432930, 9780805432930. p 91.

- ^ a b Liang, Yuansheng. [2007] (2007). The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Chinese University Press. ISBN 962996239X, 9789629962395. pg 5.

- ^ O'Hagan Muqian Luo, Paul. [2006] (2006). 讀名人小傳學英文: famous people. 寂天文化. publishing. ISBN 9861840451, 9789861840451. p16.

- ^ Xinhuanet.com. "Xinhuanet.com." 中國考古簡訊:秦始皇去世地沙丘平臺遺跡尚存. Retrieved on 2009-01-28.

- ^ a b c d The History of China. [2001] (2001). Wright, David Curtis. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 031330940X, 9780313309403. pg 49.

- ^ a b c d Tung, Douglas S. Tung, Kenneth. [2003] (2003). More Than 36 Stratagems: A Systematic Classification Based On Basic Behaviours. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1412006740, 9781412006743.

- ^ Man, John. The Terracotta Army, Bantam Press 2007 p125. ISBN 978-0593059296.

- ^ Huang, Ray. [1997] (1997). China: A Macro History. Edition: 2, revised, illustrated. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1563247313, 9781563247316. p 37

- ^ Jane Portal and Qingbo Duan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Arm, British Museum Press, 2007, p. 207

- ^ Man, John. The Terracotta Army, Bantam Press 2007 p170. ISBN 978-0593059296.

- ^ "Tomb of Qin Shi Huang".

- ^ Leffman, David. Lewis, Simon. Atiyah, Jeremy. Meyer, Mike. Lunt, Susie. [2003] (2003). China. Edition: 3, illustrated. Rough Guides publishing. ISBN 1843530198, 9781843530190. pg 290.

- ^ Loewe, Michael. Twitchett, Denis. (1986). The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521243270.

- ^ Lovell, Julia. [2006] (2006). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC-AD 2000. Grove Press. ISBN 0802118143, 9780802118141. pg 65.

- ^ Adherents.com. "Adherents.com." Michael Hart top 100. Retrieved on 2009-01-31.

- ^ Mao Zedong sixiang wan sui! (1969), p. 195. Referenced in Governing China (2nd ed.) by Kenneth Lieberthal (2004).

- ^ Southerncrossreview.org. "Southerncrossreview.org." The Wall and the Books. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ Openlibrary.org. "Openlibrary.org." The Lord of the East. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ Samuraidvd. "Samuraidvd." Shin No Shikoutei. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ Sina.com. "Sina.com.cn." 历史剧:正史侠说. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ NYTimes.com. "NYtimes.com." Film review. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ IMDB.com. "IMDB.com." Emperor and the Assassin. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ TVB. "TVB." A Step to the Past TVB. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ CCTV. "CCTV." List the 30 episode series. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ IMDB.com. "IMDB.com." San wa. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ Blockbuster. "Blockbuster." Secrets of China's First emperor. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ Historychannel.com. "Historychannel.com." China's First emperor. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ "The Mummy: Tomb Of The Dragon Emperor - After this, I want my Mummy!". Daily Mail. 2008-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gamefaqs. "Gamefaqs." Civilization IV. Retrieved on 2009-02-03.

Further reading

- Wood, Frances (2007). The First Emperor of China. Profile. ISBN 1846680328.

- Portal, Jane (2007). The First Emperor, China's Terracota Army. British Museum Press. ISBN 9781932543254&9781932543261.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)