Ahura Mazda: Difference between revisions

m →Nomenclature: fixed <ref> |

Added citation ''Equivalence from Ahura to Ashur |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

'Mazda', or rather the Avestan stem-form ''Mazdā-'', nominative ''Mazdå'', reflects Proto-Iranian ''*Mazdāh''. It is generally taken to be the proper name of the deity, and like its [[Sanskrit]] cognate ''medhā'', means "[[intelligence]]" or "[[wisdom]]". Both the Avestan and Sanskrit words reflect [[Proto-Indo-Iranian language|Proto-Indo-Iranian]] *mazdhā-, from Proto-Indo-European {{unicode|*mn̩sdʰeh<sub>1</sub>}}, literally meaning "placing ({{unicode|*dʰeh<sub>1</sub>}}) one's mind ({{unicode|*mn̩-s}})", hence "wise". |

'Mazda', or rather the Avestan stem-form ''Mazdā-'', nominative ''Mazdå'', reflects Proto-Iranian ''*Mazdāh''. It is generally taken to be the proper name of the deity, and like its [[Sanskrit]] cognate ''medhā'', means "[[intelligence]]" or "[[wisdom]]". Both the Avestan and Sanskrit words reflect [[Proto-Indo-Iranian language|Proto-Indo-Iranian]] *mazdhā-, from Proto-Indo-European {{unicode|*mn̩sdʰeh<sub>1</sub>}}, literally meaning "placing ({{unicode|*dʰeh<sub>1</sub>}}) one's mind ({{unicode|*mn̩-s}})", hence "wise". |

||

'Ahura' was originally an adjective meaning ''[[Ahura|ahuric]]'', characterizing a specific Indo-Iranian entity named ''*asura''<!-- do not link, not same as [[asura]] -->.<ref name="Thieme_1960_308">{{harvnb|Thieme|1960|p=308}}.</ref><ref name="Gershevitch_1964_23">{{harvnb|Gershevitch|1964|p=23}}.</ref><ref name="Kuiper_1983_682">{{harvnb|Kuiper|1983|p=682}}.</ref> Although traces of this figure are still evident in the oldest texts of both India and Iran,<ref name="Thieme_1960_308_309">{{harvnb|Thieme|1960|pp=308-309}}.</ref> in both cultures the word eventually appears as the epithet of other divinities. There are also speculations that the term ''Ahura'' infact equated to the Persian variety of the [[Assyrian]] God ''[[Ashur_(god)|Ashur]]'' as the [[Behistun Inscription]] referred to the Assyrians as ''Ahura'' by historians today.<ref> |

'Ahura' was originally an adjective meaning ''[[Ahura|ahuric]]'', characterizing a specific Indo-Iranian entity named ''*asura''<!-- do not link, not same as [[asura]] -->.<ref name="Thieme_1960_308">{{harvnb|Thieme|1960|p=308}}.</ref><ref name="Gershevitch_1964_23">{{harvnb|Gershevitch|1964|p=23}}.</ref><ref name="Kuiper_1983_682">{{harvnb|Kuiper|1983|p=682}}.</ref> Although traces of this figure are still evident in the oldest texts of both India and Iran,<ref name="Thieme_1960_308_309">{{harvnb|Thieme|1960|pp=308-309}}.</ref> in both cultures the word eventually appears as the epithet of other divinities. There are also speculations that the term ''Ahura'' infact equated to the Persian variety of the [[Assyrian]] God ''[[Ashur_(god)|Ashur]]'' as the [[Behistun Inscription]] referred to the Assyrians as ''Ahura'' by historians today.<ref name="Sweeney_2008_105">{{harvnb|Sweeney|2008|p=105}}.</ref> |

||

In the [[Gathas]] (Gāθās), the hymns thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself, the two halves of the name are not necessarily used together, or are used interchangeably, or are used in reverse order. However, in the younger texts of the [[Avesta]], both Ahura and Mazda are integral parts of the name Ahura Mazda, and which are conjoined in other old [[Iranian languages]]. |

In the [[Gathas]] (Gāθās), the hymns thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself, the two halves of the name are not necessarily used together, or are used interchangeably, or are used in reverse order. However, in the younger texts of the [[Avesta]], both Ahura and Mazda are integral parts of the name Ahura Mazda, and which are conjoined in other old [[Iranian languages]]. |

||

Revision as of 18:07, 23 November 2009

Ahura Mazda(Ahura Mazdā) is the Avestan language name for a divinity exalted by Zoroaster as the one uncreated Creator.

The Zoroastrian faith is described by its adherents as Mazdayasna, the worship of Mazda. In the Avesta, "Ahura Mazda is the highest object of worship"[1], the first and most frequently invoked divinity in the Yasna liturgy. In Zoroastrian cosmogony and tradition, all the lesser divinities are also creations of Mazda. (e.g., Bundahishn III)

Ahura Mazda is 𐏉 'Auramazdā'[2] in Old Persian, 'Aramazd' in Parthian[3] and Armenian, and 'Armazi' (არმაზი) in Georgian (cf. also Aramazd). Middle- and New Persian language usage varies, but 'Hourmazd', 'Hormizd', 'Hormuzd', 'Ohrmazd' and 'Ormazd/Ōrmazd' (Persian: اورمزد/ارمزد) are common transliterations.

Nomenclature

'Mazda', or rather the Avestan stem-form Mazdā-, nominative Mazdå, reflects Proto-Iranian *Mazdāh. It is generally taken to be the proper name of the deity, and like its Sanskrit cognate medhā, means "intelligence" or "wisdom". Both the Avestan and Sanskrit words reflect Proto-Indo-Iranian *mazdhā-, from Proto-Indo-European

- mn̩sdʰeh1, literally meaning "placing (

- dʰeh1) one's mind (

- mn̩-s)", hence "wise".

'Ahura' was originally an adjective meaning ahuric, characterizing a specific Indo-Iranian entity named *asura.[4][5][6] Although traces of this figure are still evident in the oldest texts of both India and Iran,[7] in both cultures the word eventually appears as the epithet of other divinities. There are also speculations that the term Ahura infact equated to the Persian variety of the Assyrian God Ashur as the Behistun Inscription referred to the Assyrians as Ahura by historians today.[8]

In the Gathas (Gāθās), the hymns thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself, the two halves of the name are not necessarily used together, or are used interchangeably, or are used in reverse order. However, in the younger texts of the Avesta, both Ahura and Mazda are integral parts of the name Ahura Mazda, and which are conjoined in other old Iranian languages.

Perceived origin

Although Ahura Mazda is thought to represent a proto-Indo-Iranian divinity, the details are a matter of speculation and debate. Scholarly consensus identifies a connection to the prototypical *vouruna and *mitra, but whether Ahura Mazda is one of these two, or both together, or even a superior of the two has not been conclusively established.

One view[9] is that the proto-Indo-Iranian divinity is the nameless "Father Asura", Varuna of the Rigveda. In this view, Zoroastrian mazda is the equivalent of the Vedic medhira, described in Rigveda 8.6.10 as the "(revealed) insight into the cosmic order" that Varuna grants his devotees. It has also been suggested[10] that Ahura Mazda could be an Iranian development of the dvandvah expression *mitra-*vouruna, with *mitra being the otherwise nameless 'Lord' (Ahura) and *vouruna being mazda/medhira as noted above. In this instance, Ahura Mazda is then a compound divinity in which the favorable characteristics of *mitra negate the unfavorable qualities of *vouruna.

Another interpretation, Ahura Mazda is seen as the Ahura par excellence, superior to both *vouruna and *mitra, and the nameless "Father Asura" of the RigVeda is a distinct divinity (see etymology above) to whom Ahura Mazda may or may not be related. In a development of this view,[11] the dvandvah expression *mitra-*vouruna is none other than the archaic 'Mithra-Baga' of the Avesta. But while in the Vedas Bhaga is a minor divinity in its own right, in proto-Indo-Iranian times this was an epithet of *vouruna's concept and in Greater Iran continued to be a cult title for *vouruna and eventually replaced it.[12] It has also been noted that on Persepolis fortification tablet #337, Ahura Mazda is distinct from both Mithra and the Baga.[13]

In Zoroaster's revelation

Although the principle of a creator divinity was not new to the two Indo-Iranian cultures, Zoroaster gives Ahura Mazda an entirely new dimension by characterizing the Creator as the one uncreated God (Yasna 30.3, 45.2). "No satisfactory evidence has yet been adduced to show that, before Zoroaster, the concept of a supreme god existed among the Iranians."[14]

Central to Zoroaster's perception of Ahura Mazda is the concept of asha, literally "truth", and in the extended sense, the equitable law of the universe, which governed the life of Zoroaster's people, the nomadic herdsmen of the Central Asian steppes.[15] For these, asha was the course of everything observable, the motion of the planets and astral bodies, the progression of the seasons, the pattern of daily nomadic herdsman life, governed by regular metronomic events such as sunrise and sunset. All physical creation (geti) was thus a product of - and ran according to - a master plan, inherent to Ahura Mazda, and violations of the order (druj) were violations against creation, and thus violations against Ahura Mazda.

This concept of asha versus the druj should not be confused with the good-versus-evil battle evident in western religions, for although both forms of opposition express moral conflict, the asha versus druj concept is more subtle and nuanced, representing, for instance, chaos (that opposes order); or 'uncreation', evident as natural decay (Avestan: nasu) that opposes creation; or more literally 'the Lie' of Yasna 31.1 (that opposes truth, righteousness).

In Zoroaster's perception of Ahura Mazda's role as the one uncreated Creator of all (Yasna 44.7), the Creator is then not also the creator of 'druj', for as anti-creation, the druj are not created (or not creatable, and thus - like Ahura Mazda - uncreated). "All" is therefore the "supreme benevolent providence" (Yasna 43.11), and Ahura Mazda as the benevolent Creator of all is consequently the Creator of only the good (Yasna 31.4). In Zoroaster's revelation, Ahura Mazda will ultimately triumph (Yasna 48.1), but cannot (or will not) control the druj in the here and now. As such, Zoroaster did not perceive Ahura Mazda to be omnipotent. Zoroaster did not hypostasize either good or evil (see asha for details).

Throughout the Gathas Zoroaster emphasizes deeds and actions, for it is only through "good thoughts, good words, good deeds" that order can be maintained, and in Zoroaster's revelation indeed the purpose of humankind is to assist in maintaining the order. In Yasna 45.9, Ahura Mazda "has left to men's wills" to choose between doing good (that is, good thoughts, good words and good deeds) and doing evil (bad thoughts, bad words and bad deeds). This concept of a free will is perhaps Zoroaster's greatest contribution to religious philosophy.

In Zurvanite Zoroastrianism

In Zurvanism, Ahura Mazda was not the transcendental God, but one of two equal-but-opposite divinities under the supremacy of Zurvan, 'Time'.

Although Zurvanism appears to have thrived during the Sassanid era (226–651), no traces of it remain beyond the 10th century. Accounts of typically Zurvanite beliefs were the first traces of Zoroastrianism to reach the west, which misled European scholars to conclude that Zoroastrianism was a monist faith.

In present-day Zoroastrianism

In 1884, Martin Haug proposed a new interpretation of Yasna 30.3 that subsequently influenced Zoroastrian doctrine to a significant extent. According to Haug's interpretation, the "twin spirits" of 30.3 were Angra Mainyu and Spenta Mainyu, the former being literally the 'Destructive Spirit'[n 1] and the latter being the 'Bounteous Spirit' (of Mazda). Further, in Haug's scheme Angra Mainyu was now not Ahura Mazda's binary opposite, but—like Spenta Mainyu—an emanation of Him. Haug also interpreted the concept of a free will of Yasna 45.9 as an accommodation to explain where Angra Mainyu came from since Ahura Mazda created only good. The free will, so Haug, made it possible for Angra Mainyu to choose to be evil.

Although these latter conclusions were not substantiated by Zoroastrian tradition[13] (and are today rejected by the academic community), at the time Haug's interpretation was gratefully accepted by the Parsis of Bombay since it provided a defense against Christian missionary rhetoric,[n 2] particularly the attacks on the Zoroastrian idea of an uncreated Evil that was as uncreated as God was. For the polemicists it followed that Zoroastrianism did not have a supreme God.

Following Haug, the Bombay Parsis began to defend themselves in the English language press; the argument being that Angra Mainyu was not Mazda's binary opposite, but His subordinate, and who—as in Zurvanism also—chose to be evil. Consequently, Haug's theories were disseminated as a Parsi interpretation, also in the West, where they appeared to be corroborating Haug. Reinforcing themselves, Haug's ideas came to be iterated so often that they are today almost universally accepted as doctrine.[16][17][n 3]

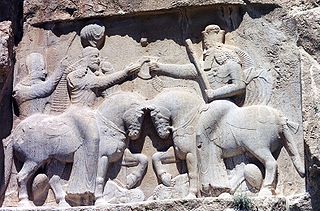

In West-Iranian iconography

From the reign of Cyrus the Great down to Darius III, it was apparently customary for an empty chariot drawn by white horses to accompany the Persian army. According to Herodotus, who first described the practice, this chariot was sacred to "Zeus" who was presumably believed to position himself at the head of the army. (Ahura Mazda was frequently named Zeus by the Greeks; Aristotle refers to Zeus-Oromasdes being opposed by Hades-Aremainius.)

The earliest reference to the use of an image to accompany devotion to Ahura Mazda is from "the 39th year of the reign of Artaxerxes Mnemon" (c. 365 BCE) in which a Satrap of Lydia raised a statue (according to the Greek commentator) to "Zeus" the Lawgiver.

The worship of Ahura Mazda with accompanying images is known to have occurred during the Arsacid era (250 BCE–226 CE), but by the beginning of the Sassanid period (226–651), the custom appears to have fallen out of favor. A few images from Sassanid times that depict "Ohrmazd", reveal a male figure wearing a high crown.

In other religions

In Manichaeism, the name Ohrmazd Bay ("god Ahura Mazda") was used for the primal figure Nāšā Qaḏmāyā, the "original man" and emmination of the Father of Greatness (in Manicheism called Zurvan) through who after he sacrificed himself to defend the world of light was consumed by the forces of darkness. Although Ormuzd is freed from the world of darkness his "sons" often called his garments or weapons remain. His sons known later known as the World Soul after a series of events will for the most part escape from matter and return again to the world of light where they came from. Manicheans often identified many of Mani's cosmological figures with Zoroastrian ones. This may be in part Mani was born in the greatly Zoroastrian Parthian Empire. However another reason for why this may be is that in Manicheism the religions of Zoroastrianism, Christianity and Buddhism were in fact deviations of the true religion that Mani taught and in a way they were the same religion, hence making it easier to identify the cosmological figures of Mani with the cosmological figures of Zoroastrianism.

In Sogdian Buddhism, Xwrmztʔ (Sogdian was written without a consistent representation of vowels) was the name used for the Buddhist ruler-deity Śakra. Via contacts with Turkic-speaking peoples like the Uyghurs, this Sogdian name came to the Mongols, who still name this deity Qormusta Tengri; Qormusta (or Qormusda) is now a popular enough deity to appear in many contexts that are not explicitly Buddhist.

Notes

- ^ For an explanation of the approximation of mainyu as "spirit", see Angra Mainyu.

- ^ Most prominent of these voices was that of the Scottish Presbyterian minister Dr. John Wilson, whose church was by coincidence next door to the K. R. Cama Athornan Institute, the premier school for Zoroastrian priests. That the opinions of the Zoroastrian priesthood is barely represented in the debates that ensued was to some extent due to the fact that the priesthood spoke Gujarati and not English, but also because they were (at the time) poorly equipped to debate with a classically-trained theologian on his footing. Wilson had even taught himself Avestan.

- ^ For a scholastic review of the theological developments in Indian Zoroastrianism, particularly with respect to the devaluation of Angra Mainyu to a position where the (epitome of) pure evil became viewed as a creation of Mazda (and so compromised their figure of pure good), see Maneck 1997.

References

- ^ Dhalla 1938, p. 154.

- ^ Kent 1945, p. 229ff.

- ^ Boyce 1983, p. 684.

- ^ Thieme 1960, p. 308.

- ^ Gershevitch 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Kuiper 1983, p. 682.

- ^ Thieme 1960, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Sweeney 2008, p. 105.

- ^ cf. Kuiper 1976, pp. 33ff.

- ^ Kuiper 1983, p. 683.

- ^ Boyce 2001, pp. 239–257.

- ^ Boyce 2001, pp. 243–244.

- ^ a b Boyce 1983, p. 685.

- ^ Boyce 2001, p. 243, n.18.

- ^ Boyce 1975, pp. 1ff

- ^ Boyce 1983, p. 686.

- ^ Maneck 1997, pp. 182ff.

Bibliography

- Boyce, Mary (1975), History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. I, The early period, Leiden: Brill

- Boyce, Mary (1982), History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. II, Under the Achamenians, Leiden: Brill

- Boyce, Mary (1983), "Ahura Mazdā", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 1, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 684–687

- Boyce, Mary (2001), "Mithra the King and Varuna the Master", Festschrift für Helmut Humbach zum 80., Trier: WWT, pp. 239–257

- Dhalla, Maneckji Nusservanji (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, New York: OUP

- Humbach, Helmut (1991), The Gathas of Zarathushtra and the other Old Avestan texts, Heidelberg: Winter

- Kent, Roland G. (1945), "Old Persian Texts", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 4 (4): 228–233

- Kuiper, Bernardus Franciscus Jacobus (1983), "Ahura", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 1, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 682–683

- Kuiper, Bernardus Franciscus Jacobus (1976), "Ahura Mazdā 'Lord Wisdom'?", Indo-Iranian Journal, 18 (1–2): 25–42

- Maneck, Susan Stiles (1997), The Death of Ahriman: Culture, Identity and Theological Change Among the Parsis of India, Bombay: K. R. Cama Oriental Institute

- Schlerath, Bernfried (1983), "Ahurānī", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 1, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 683–684