Causes of World War I: Difference between revisions

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

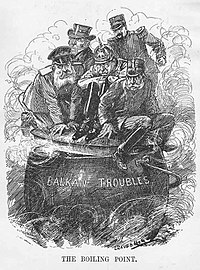

Fundamentally the war was sparked by tensions over territory in the Balkans. Austria-Hungary competed with Serbia and Russia for territory and influence in the region and they pulled the rest of the [[great power]]s into the conflict through their various alliances and treaties. |

Fundamentally the war was sparked by tensions over territory in the Balkans. Austria-Hungary competed with Serbia and Russia for territory and influence in the region and they pulled the rest of the [[great power]]s into the conflict through their various alliances and treaties. |

||

The topic of the causes of, or guilt for, the First World War is one of the most studied in all of world history. Scholars have differed significantly in their interpretations of the event. |

The topic of the causes of, or guilt for, the First World War is one of the most studied in all of world history. Scholars have differed significantly in their interpretations of the event. |

||

==Run-up== jackson is awesome why did they kill franz ferdinand, have fun. learn how to read and spell blahh |

|||

==Run-up== |

|||

{{POV-section|date=June 2009}} |

{{POV-section|date=June 2009}} |

||

From the time of the [[Balkan Wars]], which had increased the size of [[Serbia]], it had been the opinion of leading Austrian officials, most notably the Foreign Minister, Count [[Leopold von Berchtold]] that Austria would have to wage a “preventive war” to greatly weaken or destroy Serbia as a state in order to preserve the [[dual monarchy]] which held extensive Serb populated Balkan territories.<ref name=Fromkin260-62>{{Cite book | last=Fromkin | first=David | authorlink=David Fromkin | coauthors= | title=Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914? | date= | publisher=New York : Knopf : 2004. | location= | isbn=978-0375411564 | pages=260–62}}</ref>. Another important member of the War Party was the Chief of Staff, General [[Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf]], who first suggested a preventive war against Serbia in 1906, and again in 1908-09 (because of Serbian actions in the [[Bosnian Crisis]]), and 1912-13 as Serbia, now triumphant in the [[Second Balkan War]], became more aggressive regarding Austrian-Hungary's control of fellow Serbs in Bosnia.<ref name=Fromkin102>{{Cite book | last=Fromkin | first=David | authorlink=David Fromkin | coauthors= | title=Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914? | date= | publisher=New York : Knopf : 2004. | location= | isbn=978-0375411564 | pages=102}}</ref> Between January 1913 and January 1914, Conrad advocated a preventive war against Serbia twenty four times.<ref name="Fromkin102" />.[[File:Ww1-military alliances 1914.JPG|left|thumb|The alliance situation in central Europe in 1914]] |

From the time of the [[Balkan Wars]], which had increased the size of [[Serbia]], it had been the opinion of leading Austrian officials, most notably the Foreign Minister, Count [[Leopold von Berchtold]] that Austria would have to wage a “preventive war” to greatly weaken or destroy Serbia as a state in order to preserve the [[dual monarchy]] which held extensive Serb populated Balkan territories.<ref name=Fromkin260-62>{{Cite book | last=Fromkin | first=David | authorlink=David Fromkin | coauthors= | title=Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914? | date= | publisher=New York : Knopf : 2004. | location= | isbn=978-0375411564 | pages=260–62}}</ref>. Another important member of the War Party was the Chief of Staff, General [[Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf]], who first suggested a preventive war against Serbia in 1906, and again in 1908-09 (because of Serbian actions in the [[Bosnian Crisis]]), and 1912-13 as Serbia, now triumphant in the [[Second Balkan War]], became more aggressive regarding Austrian-Hungary's control of fellow Serbs in Bosnia.<ref name=Fromkin102>{{Cite book | last=Fromkin | first=David | authorlink=David Fromkin | coauthors= | title=Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914? | date= | publisher=New York : Knopf : 2004. | location= | isbn=978-0375411564 | pages=102}}</ref> Between January 1913 and January 1914, Conrad advocated a preventive war against Serbia twenty four times.<ref name="Fromkin102" />.[[File:Ww1-military alliances 1914.JPG|left|thumb|The alliance situation in central Europe in 1914]] |

||

Revision as of 02:48, 3 February 2010

The causes of the military conflict which began in central Europe in August, 1914, included many intertwined factors, including the conflicts and antagonisms of the four decades leading up to the war. Militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism played major roles in the conflict. The immediate origins of the war lay in the decisions taken by statesmen and generals during the July Crisis of 1914, the spark (or casus belli) for which was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by Gavrilo Princip, an irredentist Serb.[1] However, the crisis did not exist in a void; it came after a long series of diplomatic clashes between the Great Powers over European and colonial issues in the decade prior to 1914 which had left tensions high. In turn these diplomatic clashes can be traced to changes in the balance of power in Europe since 1870.[2] Fundamentally the war was sparked by tensions over territory in the Balkans. Austria-Hungary competed with Serbia and Russia for territory and influence in the region and they pulled the rest of the great powers into the conflict through their various alliances and treaties. The topic of the causes of, or guilt for, the First World War is one of the most studied in all of world history. Scholars have differed significantly in their interpretations of the event. ==Run-up== jackson is awesome why did they kill franz ferdinand, have fun. learn how to read and spell blahh

From the time of the Balkan Wars, which had increased the size of Serbia, it had been the opinion of leading Austrian officials, most notably the Foreign Minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold that Austria would have to wage a “preventive war” to greatly weaken or destroy Serbia as a state in order to preserve the dual monarchy which held extensive Serb populated Balkan territories.[3]. Another important member of the War Party was the Chief of Staff, General Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, who first suggested a preventive war against Serbia in 1906, and again in 1908-09 (because of Serbian actions in the Bosnian Crisis), and 1912-13 as Serbia, now triumphant in the Second Balkan War, became more aggressive regarding Austrian-Hungary's control of fellow Serbs in Bosnia.[4] Between January 1913 and January 1914, Conrad advocated a preventive war against Serbia twenty four times.[4].

As one of the victors in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, Serbia expanded its territory at the expense of the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria[5] under the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest. Regarding the expansion of Serbia as an unacceptable increase in the power of an unfriendly state and in order to weaken Serbia, the Austrian government threatened war in the autumn of 1912 if Serbs were to acquire a port from the Turks[5]. Austria appealed for German support, only to be rebuffed at first.[5]

In November 1912 Russia, humiliated by its inability to support Serbia during the Bosnian crisis of 1908 or the First Balkan War, announced a major reconstruction of its military.

On November 28, in partial reaction to the Russian move, German Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow told the Reichstag, the German parliament, that “If Austria is forced, for whatever reason, to fight for its position as a Great Power, then we must stand by her” [5]. As a result, British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey responded by warning Prince Karl Lichnowsky, the German Ambassador in London, that if Germany gave Austria a “blank cheque” for war in the Balkans, then “the consequences of such a policy would be incalculable” [5]. To reinforce this point, R. B. Haldane, the Germanophile Lord Chancellor, met with Prince Lichnowsky to offer an explicit warning that if Germany were to upset the balance of power in Europe by trying to destroy either France or Russia as powers, Britain would have no other choice, but to fight the Reich[5].

With the recently announced Russian military reconstruction and certain British communications, the possibility of war was a prime topic at the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 in Berlin, an informal meeting of some of Germany's top military leadership called on short notice by the Kaiser.[5]. Attending the conference were Wilhelm II, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz - the Naval State Secretary, Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, the Chief of the The German Imperial Naval Cabinet (Marinekabinett) , General von Moltke - the Army’s Chief of Staff, Admiral August von Heeringen - the Chief of the Naval General Staff and (probably) the Chief of the German Imperial Military Cabinet, General Moriz von Lyncker[5]. The presence of the leaders of both the German Army and Navy at this War Council attest to its importance. However, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and General Josias von Heeringen, the Prussian Minister of War, were not invited.[6]

Wilhelm II called British balance of power principles “idiocy”, but agreed that Haldane’s statement was a “desirable clarification” of British policy[5]. His opinion was that Austria should attack Serbia that December, and if “Russia supports the Serbs, which she evidently does…then war would be unavoidable for us, too,” [5] and that would be better than going to war after Russia completed the massive modernization and expansion of their army that they had just begun. Moltke agreed. In his professional military opinion “a war is unavoidable and the sooner the better” [5]. Moltke “wanted to launch an immediate attack”[7]

Both Wilhelm II and the Army leadership agreed that if a war were necessary it were best launched soon. Admiral Tirpitz, however, asked for a “postponement of the great fight for one and a half years” [5] because the Navy was not ready for a general war that included Britain as an opponent. He insisted that the completion of the construction of the U-boat base at Heligoland and the widening of the Kiel Canal were the Navy’s prerequisites for war[5]. As the British historian John Röhl has commented, the date for completion of the widening of the Kiel Canal was the summer of 1914”[7] Through Moltke objected to the postponement of the war as unacceptable, Wilhelm sided with Tirpitz[5]. Moltke “agreed to a postponement only reluctantly.”[7]

Historians more sympathetic to the government of Wilhelm II often reject the importance of this War Council as only showing the thinking, and recommendations of those present, with no decisions taken. They often cite the passage from Admiral Muller’s diary, which states: “That was the end of the conference. The result amounted to nothing.”[7] Certainly the only decision taken was to do nothing.

Historians more sympathetic to the Entente, such as British historian John Röhl, sometimes rather ambitiously interpret these words of Admiral Mueller (an advocate of launching a war soon) as saying that "nothing" was decided for 1912-13, but that war was decided on for the Summer of 1914.[7] Röhl is on safer ground when he argues that even if this War Council did not reach a binding decision - which it clearly was not - it does nonetheless offer a clear view of their intentions[7], or at least their thoughts, which were that if there was going to be a war, the German Army wanted it before the new Russian armaments program began to bear fruit.[7] Entente sympathetic historians such as Röhl see this conference in which "The result amounted to nothing.”[7] as setting a clear deadline when a war was to begin, namely the summer of 1914[7]

With the November 1912 announcement of the Russian Great Military Programme, the leadership of the German Army began clamoring even more strongly for a “preventive war” against Russia[3][5]. Moltke declared that Germany could not win the arms race with France, Britain and Russia, which she herself had began in 1911, because the financial structure of the German state, which gave the Reich government little power to tax, meant Germany would bankrupt herself in an arms race[5]. As such, Moltke from late 1912 onwards was the leading advocate for a general war, and the sooner the better[5].

Throughout May and June 1914, Moltke engaged in an “almost ultimative” demand for a German “preventive war” against Russia in 1914[7] The German Foreign Secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow reported on a discussion with Moltke at the end of May 1914:

“Moltke described to me his opinion of our military situation. The prospects of the future oppressed him heavily. In two or three years Russia would have completed her armaments. The military superiority of our enemies would then be so great that he did not know how he could overcome them. Today we would still be a match for them. In his opinion there was no alternative to making preventive war in order to defeat the enemy while we still had a chance of victory. The Chief of the General Staff therefore proposed that I should conduct a policy with the aim of provoking a war in the near-future” [7]

The new French President Raymond Poincaré, who took office in 1913, was favourable to improving relations with Germany.[8] In January 1914 Poincaré became the first French President to dine at the German Embassy in Paris[8]. Poincaré was more interested in the idea of French expansion in the Middle East than a war of revenge to regain Alsace-Lorraine [8]. Had the Reich been interested in improved relations with France before August 1914, the opportunity was available, but the leadership of the Reich lacked such interests, and preferred a policy of war to destroy France. Because of France’s smaller economy and population, by 1913, French leaders had largely accepted that France could never defeat Germany[9]

In May 1914, Serbian politics were polarized between two factions, one head by the Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, and the other by the radical nationalist chief of Military Intelligence, Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, known by his codename Apis[10]. In that month, due to Colonel Dimitrigjevic’s intrigues, King Peter dismissed Pašić’s government [10]. The Russian Minister in Belgrade intervened to have Pašić’s government restored[10]. Pašić, though he often talked tough in public, knew that Serbia was near-bankrupt and, having suffered heavy causalities in the Balkan Wars and in the suppression of a December 1913 Albanian revolt in Kosovo, needed peace[10]. Since Russia also favoured peace in the Balkans, from the Russian viewpoint it was desirable to keep Pašić in power[10]. It was in the midst of this political crisis that politically powerful members of the Serbian military armed and trained three Bosnian students as assassins and sent them into Austria-Hungary.[11]

Decisions For War

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, which Austria-Hungary had administered since 1878 and had annexed in 1908. They were shot by Gavrilo Princip, one of the three assassins sent from Belgrade. Princip was part of a group of six assassins (the three from Belgrade and three local recruits) under the coordination of Danilo Ilić. The assassins' goal was the violent separation of Bosnia-Herzegovina and possibly other provinces from Austria-Hungary, and attachment to Serbia to form a Greater Serbia or a Yugoslavia. The assassins' goals and methods are consistent with the movement that later became known as Young Bosnia.

Some scholars believe that ever since 1912, urged on by a “War Party”, of top officials, it had been the policy of Austria-Hungary to wage a war to destroy Serbia as a state [12]. However, they were restrained by a lack of German support and the fear of the Russian reaction to such a war.[12] Some members of the government, notably Archduke Franz Ferdinand, had remained much less favourably disposed toward war. In the opinion of the leaders of the “War Party”, especially the Foreign Minister Leopold von Berchtold the assassination in Sarajevo now offered the perfect excuse for the long-awaited war against Serbia.[12] Though the assassination of the very unpopular Franz Ferdinand was privately welcomed in Vienna, Berchtold argued that this was the perfect pretext to put into action the widely agreed plan for a war against Serbia.[3] On June 30, 1914 Berchtold called for a “final and fundamental reckoning” with the Serbs, and ordered his memo of June 14 to be rewritten in stronger language to take advantage of the new opportunities that Berchtold felt that the assassination of the Archduke had opened.[12] Rumours at the time that Russia was involved in the assassination have proven to be “baseless.”[3]

The news of the assassination of the Archduke, though widely greeted as a tragedy, was not generally seen as necessarily leading to a war.[13][14] In private, the Emperor Franz Josef expressed a certain degree of relief over the assassination - which rid him of an heir whom he deeply disliked - telling his daughter “For me, it is a great worry less”.[14] To an aide, the Emperor commented that “God will not be mocked. A higher power had put back the order I couldn’t maintain”.[14] An Austrian newspaper reported “the death of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand..came as a relief in wide political circles even to the highest official circles”.[14] A visitor to Vienna noted that “the event [the assassination of the Archduke] almost failed to make any impression whatever. On Sunday and Monday, the crowds in Vienna listened to music and drank wine…as if nothing had happened”.[14] The funeral of the Archduke and Archduchess were attended by all series of petty humiliations of the deceased couple, which as the historian David Fromkin noted, reflected the lack of outrage felt by the Austrian government over the asssassinations[15]. At a meeting of the French Cabinet, the assassination was “hardly mentioned”.[14]

In the aftermath of the assassinations, most of the conspirators had been arrested by July 2, 1914.[16] General Potiorek reported to the Finance Minister Bilinski that he believed that the assassins were supplied with weapons from Major Tanosic of Serbian Military Intelligence.[16] Another Austrian official reported “There is nothing to indicate that the Serbian government knew about the plot."[16] Prince M.A. Gagarin of the Russian Embassy was sent to investigate on behalf of the Russian government. Prince Gagarin commented that security for the Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been almost non-existent, that some of the suspects were Austrian subjects, and that he believed that Austrian officials were accusing the Serbian government of complicity in the assassination as a way of distracting attention from their incompetence.[16]

Those in the “War Party” in Vienna saw the assassination as an excellent excuse to execute their already pre-existing plans since 1912 for a war to destroy Serbia.[13] Berchtold used his memo of the June 14th, 1914 as the basis for the document that would be used as the basis for soliciting German support.[16] Conrad advised Berchtold that Austria-Hungary should “cut the knot’ and declare war on Serbia as soon as possible.[13] Counsels were badly divided in Vienna with Berchtold and Conrad supporting war. The Emperor Franz Josef, though receptive to the idea of a war, insisted upon German support as a prerequisite, and the Hungarian Prime Minister Count István Tisza opposed a war with Serbia under the grounds that any war with the Serbs was bound to trigger a war with Russia, and hence a general European war.[13]

Austria-Hungary immediately undertook a criminal investigation. Ilić and five of the assassins were promptly arrested and interviewed by an investigating judge. The three assassins who had come from Serbia told almost all they knew. Serbian Major Vojislav Tankosić had directly and indirectly given them six bombs (produced at the Serbian Arsenal), four pistols, training, money, suicide pills, a special map with the location of gendarmes marked, knowledge of an infiltration channel from Serbia to Sarajevo, and a card authorizing the use of that channel.

Overview

Although the war was triggered by the chain of events unleashed by the assassination, the war's origins go deeper, involving national politics, cultures, economics, and a complex web of alliances and counterbalances that had developed between the various European powers since 1870.

Some of the most important long term or structural causes are:

- The growth of nationalism across Europe

- Unresolved territorial disputes

- Intricate system of alliances

- The perceived breakdown of the balance of power in Europe

- Misperceptions of intent – e.g., the German belief the United Kingdom would remain neutral[17][18]

- Convoluted and fragmented governance

- Delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications

- Arms races of the previous decades

- Previous military planning[19]

- Imperial and colonial rivalry for wealth, power and prestige

- Economic and military rivalry in industry and trade

The various categories of explanation for World War I correspond to different historians' overall methods. Most historians and popular commentators include causes from more than one category of explanation to provide a rounded account of the causal circumstances behind the war. The deepest distinction among these accounts is that between stories which find it to have been the inevitable and predictable outcome of certain factors, and those which describe it as an arbitrary and unfortunate mistake[citation needed].

In attributing causes for the war, historians and academics had to deal with an unprecedented flood of memoirs and official documents, released as each country involved tried to avoid blame for starting the war. Early releases of information by governments, particularly those released for use by the "Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War" were shown to be incomplete and biased. In addition some documents, especially diplomatic cables between Russia and France, were found to have been doctored. Even in later decades however, when much more information had been released, historians from the same culture have been shown to come to differing conclusions on the causes of the war.[20]

Domestic Political Factors

German domestic politics

Left wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) made large gains in the 1912 German election. German government at the time was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers who feared the rise of these left wing parties. Fritz Fischer famously argued that they deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and whip up patriotic support for the government.[21] Russia was in the midst of a large scale military build-up and reform which was to be completed in 1916-17.

Other authors argue that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war, worrying that losing a war would have disastrous consequences, and even a successful war might alienate the population if it were lengthy or difficult.[22]

French domestic politics

The situation in France was quite different from Germany, but with the same results. More than a century after the French Revolution, there was still a fierce struggle between the left-wing French government and its right-wing opponents, including monarchists and "Bonapartists." A "good old war" was seen by both sides (with the exception of Jean Jaurès) as a way to solve this crisis thanks to a nationalistic reflex. For example, on July 29, after he had returned from the summit in St. Petersburg, President Poincaré was asked if war could be avoided. He is reported to have replied: "It would be a great pity. We should never again find conditions better."[23]

Everyone thought the war would be short and would lead to an easy victory.[citation needed] The left-wing government thought it would be an opportunity to implement social reforms[citation needed] (income tax was implemented in July 1914) and the right-wing politicians hoped that their connections with the army's leaders could give them the opportunity to regain power.[citation needed] Russian bribery under Poincaré's careful direction of the French press from July 1912 to 1914 played a role in creating the proper French political environment for the war.[24] Prime Minister and then President Poincaré was a strong hawk. In 1913 Poincaré predicted war for 1914.[25] In 1920 at the University of Paris, thinking back to his own student days, Poincaré remarked "I have not been able to see any reason for my generation living, except the hope of recovering our lost provinces (Alsace-Lorraine; Poincaré was born in Lorraine)." [26]

Changes in Austria

In 1867, the Austrian Empire fundamentally changed its governmental structure, becoming the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. For hundreds of years, the empire had been run in an essentially feudal manner with a German-speaking aristocracy at its head. However, with the threat represented by an emergence of nationalism within the empire's many component ethnicities, some elements, including Emperor Franz Joseph, decided that a compromise would have to be made in order to preserve the power of the German aristocracy. In 1867, the Ausgleich was agreed upon which made the Magyar elite in Hungary almost equal partners in the government of Austria-Hungary.

This arrangement fostered a tremendous degree of dissatisfaction amongst many in the traditional German ruling classes.[27] Some of them considered the Ausgleich to have been a calamity because it often frustrated their intentions in the governance of Austria-Hungary.[28] For example, it was extremely difficult for Austria-Hungary to form a coherent foreign policy that suited the interests of both the German and Magyar elite.[29]

Throughout the fifty years from 1867 to 1914, it proved difficult to reach adequate compromises in the governance of Austria-Hungary, leading many to search for non-diplomatic solutions. At the same time a form of social Darwinism became popular amongst many in the Austrian half of the government which emphasised the primacy of armed struggle between nations, and the need for nations to arm themselves for an ultimate struggle for survival.[30][31]

As a result, at least two distinct strains of thought advocated war with Serbia, often unified in the same people.

In order to deal with political deadlock, some reasoned that more Slavs needed to be brought into Austria-Hungary in order to dilute the power of the Magyar elite. With more Slavs, the South Slavs of Austria-Hungary could force a new political compromise in which the Germans would be able to play the Magyars against the South Slavs.[32] Other variations on this theme existed, but the essential idea was to cure internal stagnation through external conquest.

Another fear was that the South Slavs, primarily under the leadership of Serbia, were organizing for a war against Austria-Hungary, and even all of Germanic civilization. Some leaders, such as Conrad von Hötzendorf, argued that Serbia must be dealt with before it became too powerful to defeat militarily.[33]

A powerful contingent within the Austro-Hungarian government was motivated by these thoughts and advocated war with Serbia long before the war began. Prominent members of this group included Leopold von Berchtold, Alexander Hoyos, and Janós Forgách Graf von Ghymes und Gács. Although many other members of the government, notably Franz Ferdinand, Franz Joseph, and many Hungarian politicians did not believe that a violent struggle with Serbia would necessarily solve any of Austria-Hungary's problems, the hawkish elements did exert a strong influence on government policy, holding key positions.[32]

Samuel R. Williamson has emphasized the role of Austria-Hungary in starting the war. Convinced Serbian nationalism and Russian Balkan ambitions were disintegrating the Empire, Austria-Hungary hoped for a limited war against Serbia and that strong German support would force Russia to keep out of the war and weaken its Balkan prestige.[34]

International Relations

Imperialism

Some scholars have attributed the start of the war to imperialism.[35] Countries such as the United Kingdom and France accumulated great wealth in the late 19th century through their control of foreign resources, markets, territories, and people.[citation needed] Other empires, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Russia all hoped to do so as well. Their conflicting ambitions created tensions between them. In addition, the rapid exhaustion of natural resources in many European nations began to slowly upset the trade balance and make nations more eager to seek new territories rich in natural resources.[citation needed] Intense rivalries developed between the emerging economic powers and the incumbent great powers.

Rivalries among the great powers were exacerbated starting in the 1880s by the scramble for colonies which brought much of Africa and Asia under European rule in the following quarter-century, it also created great Anglo-French and Anglo-Russian tensions and crises that prevented a British alliance with either until the early twentieth century. Otto von Bismarck disliked the idea of an overseas empire, but pursued a colonial policy to court domestic political support. This started Anglo-German tensions since German acquisitions in Africa and the Pacific threatened to impinge upon British strategic and commercial interests. Bismarck supported French colonization in Africa because it diverted government attention and resources away from continental Europe and revanchism. In spite of all of Bismarck's deft diplomatic maneuvering, in 1890 he was forced to resign by the new Kaiser (Wilhelm II). His successor, Leo von Caprivi, was the last German Chancellor who was successful in calming Anglo-German tensions. After his loss of office in 1894, German policy led to greater conflicts with the other colonial powers.

The status of Morocco had been guaranteed by international agreement, and when France attempted to greatly expand its influence there without the assent of all the other signatories Germany opposed it prompting the Moroccan Crises, the Tangier Crisis of 1905 and the Agadir Crisis of 1911. The intent of German policy was to drive a wedge between the British and French, but in both cases produced the opposite effect and Germany was isolated diplomatically, most notably lacking the support of Italy despite Italian membership in the Triple Alliance. The French protectorate over Morocco was officially established in 1912.

In 1914 there were no outstanding colonial conflicts, Africa having been essentially fully claimed, apart from Ethiopia, for several years. However, the competitive mentality, as well as a fear of "being left behind" in the competition for the world's resources may have played a role in the decisions to begin the conflict.[citation needed]

Web of alliances

A loose web of alliances around the European nations (many of them requiring participants to agree to collective defense if attacked):

- Treaty of London, 1839, about the neutrality of Belgium,

- German-Austrian treaty (1879) or Dual Alliance,

- Italy joining Germany and Austria in 1882,

- Franco-Russian Alliance (1894),

- "Entente" (less formal) between Britain and France (1904) and Britain and Russia (1907) forming the Triple Entente,

This complex set of treaties binding various players in Europe together prior to the war is sometimes thought to have been misunderstood by contemporary political leaders. The traditionalist theory of "Entangling Alliances" has been shown to be mistaken; The Triple Entente between Russia, France and the United Kingdom did not in fact force any of those powers to mobilize because it was not a military treaty. Mobilization by a relatively minor player would not have had a cascading effect that could rapidly run out of control, involving every country. The crisis between Austria-Hungary and Serbia could have been a localized issue. This is how Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against Serbia resulted in Britain declaring war on Germany:

- June 28, 1914: Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria is assassinated by Serbian irredentists.

- July 23: Austro-Hungarian demarche made to Serbia.

- July 25: Russia enters period preparatory to war, mobilization begins on all frontiers. Government decides on partial mobilization in principal to begin on July 29.

- July 25: Serbia mobilizes its army; responds to Austro-Hungarian demarche with less than full acceptance; Austria-Hungary breaks diplomatic relations with Serbia.

- July 26: Serbia reservists accidentally violate Austro-Hungarian border at Temes-Kubin.[36]

- July 28: Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia and mobilizes against Serbia only.

- July 29: Russian general mobilization ordered, then changed to partial mobilization.

- July 30: Russian general mobilization reordered at 5PM.

- July 31: Austrian general mobilization is ordered.

- July 31: Germany enters period preparatory to war.

- July 31: Germany demands a halt to Russian military preparations within 12 hours.

- August 1: French general mobilization is ordered.

- August 1: German general mobilization is ordered.

- August 1: Germany declares war against Russia.

- August 2: Germany and The Ottoman Empire sign a secret treaty[37] entrenching the Ottoman-German Alliance

- August 3: Germany, after France declines (See Note) its demand to remain neutral,[38] declares war on France.

- August 4: Germany invades Belgium according to the modified Schlieffen Plan.

- August 4: Britain declares war on Germany.

- August 6: Austria-Hungry declares war on Russia.

- August 23: Japan, honoring the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, declares war on Germany.

Note: French Prime Minister Rene Viviani merely replied to the German ultimatum that "France will act in accordance with her interests".[38] Had the French agreed to remain neutral, the German Ambassador was authorized to ask the French to temporarily surrender the Fortresses of Toul and Verdun as a guarantee of neutrality.

Arms Race

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2009) |

As David Stevenson has put it, "A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness ... was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster ... The armaments race ... was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities". David Herrmann goes further, arguing that the fear that "windows of opportunity for victorious wars" were closing, "the arms race did precipitate the First World War". If Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, Herrmann speculates, there might have been no war; it was "the armaments race ... and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars" which made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.[39]

| The naval strength of the powers in 1914 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Personnel | Large

Naval Vessels (Dreadnoughts) |

Tonnage |

| Russia | 54,000 | 4 | 328,000 |

| France | 68,000 | 10 | 731,000 |

| Britain | 209,000 | 29 | 2,205,000 |

| TOTAL | 331,000 | 43 | 3,264,000 |

| Germany | 79,000 | 17 | 1,019,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 16,000 | 4 | 249,000 |

| TOTAL | 95,000 | 21 | 1,268,000 |

| (Source: Ferguson 1999, p. 85) | |||

The German naval buildup is seen by some historians as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations.

The overwhelming British response, however, proved to Germany that its efforts were unlikely to equal the Royal Navy. In 1900, the British had a 3.7:1 tonnage advantage over Germany; in 1910 the ratio was 2.3:1 and in 1914, 2.1:1. Ferguson argues that "so decisive was the British victory in the naval arms race that it is hard to regard it as in any meaningful sense a cause of the First World War".[40] This ignores the fact that the Kaiserliche Marine had narrowed the gap by nearly half, and that the Royal Navy had long felt (reasonably enough) a need to be stronger than any two potential opponents; the United States Navy was in a period of growth, making the German gains very ominous.

The Russian Czar had originally proposed The Hague peace conference of 1899 and also the second conference of 1907 for the purpose of disarmament, which was supported by all the signatories except for Germany. Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation. The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed.

Anglo–German naval race

Motivated by Wilhelm II’s enthusiasm for an expanded German navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz championed four Fleet Acts from 1898 to 1912 and from 1903 to 1910, the Royal Navy embarked on its own massive expansion to keep ahead of the Germans. This competition came to focus on the revolutionary new ships based on the Dreadnought, which was launched in 1906.

By 1913 there was intense internal debate about new ships due to the growing influence of John Fisher's ideas and increasing financial constraints. It is now generally accepted by historians that in early-mid 1914 the British adopted a policy of building submarines instead of new dreadnoughts and destroyers, effectively abandoning the two power standard, but kept this new policy secret so that other powers would be delayed in following suit[41].

Although the naval race as such was abandoned by the British before the war broke out, it had been one of the chief factors in England’s joining the Triple Entente and therefore important in the formation of the alliance system as a whole.

Technical/Military Factors

Over by Christmas

The belief that a war in Europe would be swift, decisive and "over by Christmas" is often considered a tragic underestimation;[42] if it had been widely thought beforehand that the war would open such an abyss under European civilization, it would not likely have been prosecuted.

This account is less plausible on a review of the available military theory at the time, especially the work of Ivan Bloch, an early candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize.[citation needed] Bloch's predictions of industrial warfare leading to bloody stalemate, attrition, and even revolution, were widely known in both military and pacifist circles. Some authors such as Niall Ferguson argue that the belief in a swift war has been greatly exaggerated since the war.[22] He argues that the military planners, especially in Germany, were aware of the potential for a long war, as shown by the famous Willy-Nicky telegraphic correspondence between the emperors of Russia and Germany. He also argues that most informed people considered a swift war unlikely. However, it was in the belligerent governments' interests to convince their populaces that the war would be brief through skillful use of propaganda, since such a message encouraged men to join the offensive, made the war seem less serious and promoted general high spirits.

Primacy of the offensive and war by timetable

Template:Associated main Military theorists of the time generally held that seizing the offensive was extremely important. This theory encouraged all belligerents to strike first in order to gain the advantage. The window for diplomacy was shortened by this attitude. Most planners wanted to begin mobilization as quickly as possible to avoid being caught on the defensive.

Some analysts have argued that mobilization schedules were so rigid that once it was begun, they could not be cancelled without massive disruption of the country and military disorganization and so diplomatic overtures conducted after the mobilizations had begun were ignored[43]. However in practice these timetables were not always decisive. The Czar ordered general mobilization canceled on July 29 despite his chief of staff's objections that this was impossible[44], a similar cancellation was made in Germany by the Kaiser on August 1 over the same objections,[45] although in theory Germany should have been the country most firmly bound by its mobilization schedule.

Schlieffen Plan

Germany's strategic vulnerability, sandwiched between its allied rivals, led to the development of the audacious Schlieffen Plan. Its aim was to knock France instantly out of contention, before Russia had time to mobilize its gigantic human reserves. It aimed to accomplish this task within 6 weeks. Germany could then turn her full resources to meeting the Russian threat. Although Count Alfred von Schlieffen initially conceived the plan prior to his retirement in 1906, Japan's defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 exposed Russia's organizational weakness and added greatly to the plan's credibility.

The plan called for a rapid German mobilization, sweeping through the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Belgium, into France. Schlieffen called for overwhelming numbers on the far right flank, the northernmost spearhead of the force with only minimum troops making up the arm and axis of the formation as well as a minimum force stationed on the Russian eastern front.

Schlieffen was replaced by Helmuth von Moltke, and in 1907–08 Moltke adjusted the plan, reducing the proportional distribution of the forces, lessening the crucial right wing in favor of a slightly more defensive strategy. Also, judging Holland unlikely to grant permission to cross its borders, the plan was revised to make a direct move through Belgium and an artillery assault on the Belgian city of Liège. With the rail lines and the unprecedented firepower the German army brought, Moltke did not expect any significant defense of the fortress.

The significance of the Schlieffen Plan is that it forced German military planners to prepare for a pre-emptive strike when war was deemed unavoidable; otherwise Russia would have time to mobilize, and Germany would be crushed by Russia's massive army. On August 1, Kaiser Wilhelm II briefly became convinced that it might be possible to ensure French and British neutrality and cancelled the plan despite the objections of the Chief of Staff that this could not be done and resuming it only when the offer of a neutral France and Britain was withdrawn[45].

It appears that no war planners in any country had prepared effectively for the Schlieffen Plan. The French were not concerned about such a move because they were confident that their offensive, Plan XVII, would break the German center and cut off the German right wing moving through Belgium and because German forces were expected to be tied down by an early Russian offensive in East Prussia.

Specific events

Franco–Prussian War (1870–1871)

Many of the direct origins of World War I can be seen in the results and consequences of the Franco-Prussian War. This conflict brought the establishment of a powerful and dynamic Germany, causing what was seen as a displacement or unbalancing of power: this new and prosperous nation had the industrial and military potential to threaten Europe, and particularly the already established European powers. Germany’s nationalism, its natural resources, its economic strengths and its ambitions sparked colonial and military rivalries with other nations, particularly the Anglo-German naval arms race.

A legacy of animosity grew between France and Germany following the German annexation of parts of the formerly French territory of Alsace-Lorraine. The annexation caused widespread resentment in France, giving rise to the desire for revenge, known as revanchism. French sentiments wanted to avenge military and territorial losses, and the displacement of France as the pre-eminent continental military power. French defeat in the war had sparked political instability, culminating in a revolution and the formation of the French Third Republic. Bismarck was wary of this during his later years and tried to placate the French by encouraging their overseas expansion. However, anti-German sentiment remained. A Franco–German colonial entente that was made in 1884 in protest of an Anglo–Portuguese agreement in West Africa proved short-lived after a pro-imperialist government under Jules Ferry in France fell in 1885.

War in Sight crisis

France quickly recovered from its defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. France paid its war remunerations and began to build its military strength again. Bismarck allowed the idea that Germany was planning a preventative war against France to be leaked via a German newspaper so that this recovery could not be realized. However, the Dreikaiserbund sided with France rather than Germany, humiliatingly forcing Bismarck to back down.

Bosnian Annexation Crisis

Austria-Hungary, desirous of solidifying its position in Bosnia-Herzegovina, annexed the provinces on October 6, 1908.[46] The annexation set off a wave of protests and diplomatic maneuvers that became known as the Bosnian crisis, or annexation crisis. The crisis continued until April 1909, when the annexation received grudging international approval through amendment of the Treaty of Berlin. During the crisis, relations between Austria-Hungary, on the one hand, and Russia and Serbia, on the other, were permanently damaged.

After an exchange of letters outlining a possible deal, Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Aehrenthal met privately at Buchlau Castle in Moravia on September 16, 1908. At Buchlau the two agreed that Austria-Hungary could annex the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which Austria-Hungary occupied and administered since 1878 under a mandate from the Treaty of Berlin. In return, Austria-Hungary would withdraw its troops from the Ottoman Sanjak of Novibazar and support Russia in its efforts to amend the Treaty of Berlin to allow Russian war ships to navigate the Straits of Constantinople during times of war. The two jointly agreed not to oppose Bulgarian independence.

While Izvolsky moved slowly from capital to capital vacationing and seeking international support for opening the Straits, Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary moved swiftly. On October 5 Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The next day, Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina. On October 7, Austria-Hungary announced its withdrawal from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. Russia, unable to obtain Britain's assent to Russia's Straits proposal, joined Serbia in assuming an attitude of protest. Britain lodged a milder protest, taking the position that annexation was a matter concerning Europe, not a bilateral issue, and so a conference should be held. France fell in line behind Britain. Italy proposed the conference be held in Italy. German opposition to the conference and complex diplomatic maneuvering scuttled the conference. On February 20, 1909, the Ottoman Empire, acquiesced to the annexation and received ₤2.2 million from Austria-Hungary.[47]

Austria-Hungary began releasing secret documents in which Russia, since 1878, had repeatedly stated that Austria-Hungary had a free hand in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novibazar. At the same time, Germany stated it would only continue its active involvement in negotiations if Russia accepted the annexation. Under these pressures, Russia agreed to the annexation,[48] and persuaded Serbia to do the same. The Treaty of Berlin was then amended by correspondence between capitals from April 7 to April 19, 1909 to reflect the annexation.

The Balkan Wars 1912-1913

The Balkan Wars in 1912-1913 led to increased international tension between Russia and Austria as well as a strengthening of Serbia and a weakening of Turkey and Bulgaria which might otherwise have kept Serbia in check thus disrupting the balance of power in Europe in favor of Russia.

Russia initially agreed to avoid territorial changes, but later in 1912 supported Serbia's demand for an Albanian port. An international conference was held in London in 1912-1913 where it was agreed to create an independent Albania , however both Serbia and Montenegro refused to comply. After an Austrian, and then an international naval demonstration in early 1912 and Russia's withdrawal of support Serbia backed down. Montenegro was not as compliant and on May 2 the Austrian council of ministers met and decided to give Montenegro a last chance to comply and if it would not then to resort to military action, however seeing the Austrian military preparations the Montenegrins requested the ultimatum be delayed and complied[49].

The Serbian government having failed to get Albania now demanded the other spoils of the First Balkan War be reapportioned, and Russia failed to pressure it to back down. Serbia and Greece allied against Bulgaria, which responded with a pre-emptive strike against their forces beginning the Second Balkan War[50]. The Bulgarian army however crumpled quickly when Turkey and Romania joined the war.

The Balkan Wars strained the German/Austro-Hungarian alliance. The attitude of the German government to Austrian requests of support against Serbia was initially both divided and inconsistent. However, after the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912, it was clear that Germany was not ready to support Austria-Hungary in a war against Serbia and her likely allies.

Also, German diplomacy before, during, and after the Second Balkan War was pro-Greek and pro-Romanian and in opposition with Austria-Hungary's increasingly pro-Bulgarian views. The result was tremendous damage to Austro-German relations. Austrian foreign minister Leopold von Berchtold remarked to German ambassador Heinrich von Tschirschky in July 1913 that "Austria-Hungary might as well belong ‘to the other grouping’ for all the good Berlin had been"[51].

In September 1913 it was learned that Serbia was moving into Albania and Russia was doing nothing to restrain it while the Serbian government would not guarantee to respect Albania's territorial integrity and suggested there would be some frontier modifications. In October 1913 it was decided by the council of ministers that Serbia be sent a warning followed by an ultimatum, that Germany and Italy be notified that there would be some action and asked for support, and that spies be sent to ascertain if there was an actual withdrawal. Serbia responded to the warning with defiance and the Ultimatum was dispatched on October 17 and received on the 18th demanding Serbia evacuate Albanian territory within eight days. Serbia complied and the Kaiser made a congratulatory visit to Vienna try to fix some of the damage done earlier in the year[52].

The conflicts demonstrated that a localized war in the Balkans could alter the balance of power without provoking general war and reinforced the attitude in the Austrian government that had been developing since the Bosnian annexation crisis that ultimatums were the only effective means of influencing Serbia and that Russia would not back its refusal with force. They also dealt catastrophic damage to the Hapsburg economy.

Historiography

1920s–1930s

During the period immediately following the end of hostilities, Allied historians argued that Germany was solely responsible for the start of the war; a view heavily influenced by the inclusion of 'war guilt' clauses within the Treaty of Versailles. In 1916 Prince Lichnowsky had also circulated his views within Germany on the mishandling of the situation in July 1914.

In 1919, the German diplomat Bernhard von Bülow (not to be confused with his more famous uncle, the former Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow) went through the German archives to suppress any documents that might show that Germany was responsible for the war, and to ensure that only documents that were exculpatory might be seen by historians.[53] As a result of Bülow's efforts, between 1923–27 the German Foreign Ministry published forty volumes of documents, which as the German-Canadian historian Holger Herwig noted were carefully edited to promote the idea that the war was not the fault of any one nation, but were rather the result of the break-down of international relations in general.[53] In addition, certain documents such as some of the papers of the Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, which did not support this interpretation were simply destroyed.[53] Those few German historians in the 1920s such as Hermann Kantorowicz, who argued that Germany was responsible for the war found that the Foreign Ministry went out of its way to stop their work from being published, and attempted to have him fired from his post at Kiel University.[53] After 1933, Kantorowicz who as a German Jew would have been banned from publishing anyhow, was forced to leave Germany for his "unpatriotic" writings.[53] With the exceptions of the work of scholars such Kantorowicz, Herwig has concluded that the majority of the work published on the subject of World War I's origins in Germany prior to Fritz Fischer's book Griff nach der Weltmacht was little more than a pseudo-historical "sham".[53]

However, academic work in the English-speaking world in the later 1920s and 1930s blamed all participants more or less equally. Starting in the early-1920s, several American historians opposed to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles such as Sidney Bradshaw Fay, Tyler Barchek, Charles Beard and Harry Elmer Barnes produced works that claimed that Germany was not responsible for war, and as such, Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which had seemingly assigned all responsibility for the war to Germany and thus justified the Allied claim to reparations, was invalid.[53] A recurring feature of the American "revisionist" historians of the 1920s was a tendency to treat Germany as a victim of the war, and the Allies as the aggressors[54] The objective of Fay and Barnes was to put an end to reparations imposed on Germany by attempting to prove what they regarded as the moral invalidity of Article 231. The exiled Wilhelm praised Barnes upon meeting him in 1926. According to Barnes, Wilhelm "was happy to know that I did not blame him for starting the war in 1914. He disagreed with my view that Russia and France were chiefly responsible. He held that the villains of 1914 were the international Jews and Free Masons, who he alleged, desired to destroy national states and the Christian religion"[55]

The German Foreign Ministry lavished special "care" upon the efforts of both Fay and Barnes with generous use of the German archives and in the case of Barnes, research funds provided by the German government.[53] The German government liked Fay's book so much that it purchased hundreds of copies of Fay's The Origin of the War in various languages to hand out for free at German embassies and consulates all around the world.[53] Likewise, the German government allowed books that were pro-German in their interpretation such as Barnes's The Genesis of the World War to be translated into German while books such as Bernadotte Schmitt's The Coming of War 1914 that were critical of German actions in 1914 were not permitted to be published in Germany.[53]

Chapter 10 of the William II's Memoirs is entitled "The Outbreak of War." In it the Kaiser lists 12 "proofs," from the more extensive "Comparative Historical Tables" that he had compiled, which demonstrate the preparations for war by the Entente Powers made in the spring and summer of 1914.[56] In particular he alleged:

- (5) According to the memoirs of the then French Ambassador at St. Petersburg, M. Paléologue, published in 1921 in the Revue des Deux Mondes, The Grand Duchesses Anastasia and Militza told him, on July 22, 1914, at Tsarskoe Selo, that their father, the King of Montenegro, had informed them in a cipher telegram, "we shall have war before the end of the month [that is, before the 13th of August, Russian style] ... nothing will be left of Austria. ... You will take Alsace-Lorraine. ... Our armies will meet at Berlin. ... Germany will be annihilated."

In a different approach, Lenin in his pamphlet Imperialism — the Highest Stage of Capitalism portrayed the war as imperialist, caused by rivalries triggered by highly organised financial monopolies, that frenzied competition for markets and raw materials had inevitably brought about the war. Evidence of secret deals between the Tsar and British and French governments to split the spoils of war was released by the Soviets in 1917–18. In the 1920s and 1930s, more socialist works built on this theme, a line of analysis which is still to be found today, although vigorously disputed on the grounds that wars occurred before the capitalist era.[57] Lenin argued that the private ownership of the means of production in the hands of a limited number of capitalist monopolies would inevitably lead to war. He identified railways as a 'summation' of the basic capitalist industries, coal, iron and steel, and that their uneven development summed up capitalist development on a worldwide scale.[58]

The National Socialist approach to the question of the war's origins were summed up in a pamphlet entitled Deutschkunde uber Volk, Staat, Leibesubungen. In 1935, the British ambassador to Germany, Sir Eric Phipps summed up the contents of Deutschkunde uber Volk, Staat, Leibesubungen which described the origins of the war thus

"Not Germany, but England, France and Russia prepared for war soon after the death of Bismarck. But Germany has also guilt to bear. She could have prevented the world war on three fronts, if she had not waited so long. The opportunity presented itself often-against England in the Boer War, against Russia when she was engaged against Japan...That she did not do so is Germany's guilt, though a proof that she was peaceful and wanted no war".[59]

In the inter-war period, various factors such as the network of secret alliances, emphasis on speed of offence, rigid military planning, Darwinian ideas, and the lack of resolution mechanisms were blamed by many historians. These ideas have maintained some currency in the decades since then. Famous proponents include Joachim Remak and Paul Kennedy. At the same time, many one sided works were produced by politicians and other participants often trying to clear their own names. In Germany these tended to deflect blame, while in Allied countries they tended to blame Germany or Austria-Hungary.

The Fischer Controversy

In 1961, the German historian Fritz Fischer published the very controversial Griff nach der Weltmacht, in which Fischer argued that the German government had expansionist foreign policy goals, formulated in the aftermath of Social Democratic gains in the election of 1912, and had deliberately started a war of aggression in 1914. Fischer was the first historian to draw attention to the War Council held by the Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Reich's top military-naval leadership on December 8, 1912 in which it was declared that Germany would start a war of aggression in the summer of 1914.[60] Both the Kaiser and the Army leadership wanted to start a war at once in December 1912, but objections from Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who while supporting the idea of starting a world war, argued that the German Navy needed more time to prepare, and asked that the war be put off until the summer of 1914.[61] The Kaiser agreed to Tirpitz's request.[62] In 1973, the British historian John Röhl noted that in view of what Fischer had uncovered, especially the War Council meeting of December 8, 1912 that the idea that Germany bore the main responsibility for the war was no longer denied by the vast majority of historians[63], although Fischer himself later denied ever having maintained that the war was decided upon at that meeting.[64] Annika Mombauer in contrast to Röhl observed in her work on Helmuth von Moltke that despite a great deal of research and debate "there is no direct evidence to prove that military decision-makers understood December 1912 as a decisive moment at which a future war had been agreed upon".[65]

Fischer's discovery of Imperial German government documents calling for the ethnic cleansing of Russian Poland and the subsequent German colonization in order to provide Germany with Lebensraum (living space) as a war aim, has also led to the widespread acceptance within the historians' community of a basic continuity between the foreign policies of Germany in 1914 and 1939.[66][67]

Fischer alleged the German government hoped to use external expansion and aggression to check internal dissent and democratization. Some of his work is based on Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg's Septemberprogramm which laid out Germany's war aims. Moreover, and even more controversially, Fischer asserted a version of the Sonderweg thesis that drew a connection between aggression in 1914 and 1939. Fischer was later to call Bethmann-Hollweg the "Hitler of 1914". Fischer spawned a whole school of analysis in a similar vein known as the Primat der Innenpolitik ("primacy of domestic politics") school, emphasizing domestic German political factors. Some prominent scholars in this school include Imanuel Geiss, Hans-Ulrich Wehler,Wolfgang Mommsen, and Volker Berghahn.

The "Berlin War Party" thesis and variants of it, blaming domestic German political factors, became something of an orthodoxy in the years after publication. However, many authors have attacked it. At first, the idea prompted a strong response, especially from German conservative historians such as Gerhard Ritter who felt the thesis was dishonest and inaccurate. Ritter believed that Germany displayed all the same traits as other countries and could not be singled out as particularly responsible. In a 1962 essay, Ritter contended that Germany's principal goal in 1914 was to maintain Austria-Hungary as a great power, and thus German foreign policy was largely defensive as opposed to Fischer's claim that it was mostly aggressive.[68] Ritter claimed that the significance that Fischer attached to the highly bellicose advice about waging a "preventive war" in the Balkans offered in July 1914 to the Chief of Cabinet of the Austro-Hungarian foreign ministry, Count Alexander Hoyos by the German journalist Viktor Naumann was unwarranted.[68] Ritter charged that Naumann was speaking as a private individual, and not as Fischer claimed on behalf of the German government.[68] Likewise, Ritter felt that Fischer had been dishonest in his portrayal of Austro-German relations in July 1914.[68] Ritter charged that it was not true that Germany had pressured a reluctant Austria-Hungary into attacking Serbia.[68] Ritter argued that the main impetus for war within Austria-Hungary was internally driven, and though there were divisions of opinion about the best course to pursue in Vienna and Budapest, it was not German pressure that led to war being chosen as the best option.[68] In Ritter's opinion, the most Germany can be criticized for in July 1914 was a mistaken evaluation of the state of European power politics.[68] Ritter claimed that the German government had underrated the state of military readiness in Russia and France, falsely assumed that British foreign policy was more pacific than what it really was, overrated the sense of moral outrage caused by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on European opinion, and above all, overestimated the military power and political common sense of Austria-Hungary.[68] Ritter felt that in retrospect that it was not necessary from the German point of view to maintain Austria-Hungary as a great power, but claimed that at the time, most Germans regarded the Dual Monarchy as a "brother empire", and viewed the prospect of the Balkans being in the Russian sphere of influence as an unacceptable threat.[68] Ritter argued that through the Germans supported the idea of an Austrian-Hungarian invasion of Serbia, this was more of an ad hoc response to the crisis gripping Europe as opposed to Fischer's claim that Germany was deliberately setting off a war of aggression.[68] Finally, Ritter complained that Fischer relied too much on the memories of Austro-Hungarian leaders such as the Count István Tisza and Count Ottokar Czernin who sought to shift all of the responsibility for the war on German shoulders.[68] Ritter ended his essay by writing he felt profound "sadness" over the prospect that the next generation of Germans would not be as nationalistically-minded as previous generations as a result of reading Fischer.[68]

The so-called "Fischer Controversy" witnessed savage attacks on Fischer, with Ritter writing to Karl Dietrich Erdmann on May 25, 1962 stating: "I am ready for any form of cooperaton with you, in the hope that we will slay the monster of the new historical legend!"[69] In private, Ritter admitted that the documenatary evidence supported Fischer. In a letter to Hans Rothfels on March 26, 1962, just before publishing an article attacking Fischer, Ritter wrote:

"I am alarmed and dismayed by your letter of 21 March. If Bethmann, as you write, in July 1914 had the 'desire' [Wunsch] to bring about war with Russia, then either he played without conscience with the fate of the German people, or he had simply incredible illusions about our military capablilities. In any case, Fischer would then be completely in the right when he denies that Bethmann seriously wanted to avoid war...If what in your view, Riezler's diary reveals is correct, I would have to discard my article, instead of publishing it...In any case we are dealing here with a most ominous [unheimlichen] state secret, and all historical perspectives are displaced [verschieben sich], since...Bethmann Hollweg's September Program then appears in a wholly different light".[70]

Later Works

In the 1960s, two new rival theories emerged to explain the causes of World War I. The first, championed by the West German historian Andreas Hillgruber argued that in 1914, a "calculated risk" on the part of Berlin had gone awry.[71] Hillgruber argued that what the Imperial German government had attempted to do in 1914 was to break the informal Triple Entente of Russia, France and Britain, by encouraging Austria-Hungary to invade Serbia and thus provoke a crisis in an area that would concern only St. Petersburg. Hillgruber argued that the Germans hoped that both Paris and London would decide the crisis in the Balkans did not concern them and that lack of Anglo-French support would lead the Russians to reach an understanding with Germany. Hillgruber argued that when the Austrian attack on Serbia caused Russia to mobilize instead of backing down as expected, the German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg under strong pressure from a hawkish General Staff led by General Motke the Younger panicked and ordered the Schlieffen Plan to be activated, thus leading to a German attack on France. In Hillgruber’s opinion, the German government had pursued a high-risk diplomatic strategy of provoking a war in the Balkans that had inadvertently caused a world war.[72]

Another theory was A.J.P. Taylor's "Railway Thesis" in his 1969 book War by Timetable. In Taylor's opinion, none of the great powers wanted a war, but all of the great powers wished to increase their power relative to the others. Taylor argued that by engaging in an arms race and having the general staffs develop elaborate railway timetables for mobilization, the continental powers hoped to develop a deterrent that would lead the other powers to see the risk of war as being too dangerous. When the crisis began in the summer of 1914, Taylor argued, the need to mobilize faster than one's potential opponent made the leaders of 1914 prisoners of their own logistics. The railway timetables forced invasion (of Belgium from Germany) as an unavoidable physical and logistical consequence of German mobilization. In this way, Taylor argued, the mobilization that was meant to serve as a threat and deterrent to war instead relentlessly caused a world war by forcing invasion. Many have argued that Taylor, who was one of the leaders of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, developed his Railway Thesis to serve as a thinly veiled admonitory allegory for the nuclear arms race.

Other authors such as the American Marxist historian Arno J. Mayer, in 1967, agreed with some aspects of the "Berlin War Party" theory, but felt that what Fischer said applied to all European states. In a 1967 essay "The Primacy of Domestic Politics", Mayer made a Primat der Innenpolitik ("primacy of domestic politics") argument for the war's origins. Mayer rejected the traditional Primat der Außenpolitik ("primacy of foreign politics") argument of traditional diplomatic history under the grounds that it failed to take into account that in Mayer's opinion, all of the major European countries were in a "revolutionary situation" in 1914.[73] In Mayer's opinion, in 1914, Britain was on the verge of civil war and massive industrial unrest, Italy had been rocked by the Red Week of June 1914, France and Germany were faced with ever-increasing political strife, Russia was facing a huge strike wave, and Austria-Hungary was confronted with rising ethnic and class tensions.[73] Moreover, Mayer insists that liberalism was disintegrating in face of the challenge from the extreme right and left in Britain, France and Italy while being a non-existent force in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia.[73] Mayer ended his essay by arguing that World War I should be best understood as a pre-emptive "counterrevolutionary" strike by ruling elites in Europe to preserve their power.[73]

In a 1972 essay "World War I As A Galloping Gertie", the American historian Paul W. Schroeder blamed Britain for the First World War. Schroeder argued that the war was a "Gallopoing Gertie", in events escalated out of control, sucking in all of the Great Powers into an unwanted war.[74] Schroeder that the key factor in the European situation was what he claimed was Britain's “encirclement" policy directed at Austria-Hungary.[74] Schroeder argued that British foreign policy was fundamentally anti-German, and even more so, anti-Austrian.[74] Schroeder argued that because Britain never took Austria-Hungary serioulsly, it was British policy to always force concessions on the Dual Monarchy with no regard to the balance of power in Central Europe.[74] Schroeder claimed that 1914 was a "preventive war" forced on Germany to maintain Austria as a power, which faced with a crippling British "encirclement policy" aimed at the break-up of that state.[74]

The American historian Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. lays most of the blame with the Austro-Hungarian elites rather than the Germans in his 1990 book, Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. Another recent work is Niall Ferguson's The Pity of War which completely rejects the Fischer thesis, laying most of the blame on diplomatic bumbling from the British.

Recently, American historian David Fromkin has allocated blame for the outbreak of war entirely to elements in the military leadership of Germany and Austria-Hungary in his 2004 book Europe's Last Summer. Fromkin's thesis is that there were two war plans; a first formulated by Austria-Hungary and the German Chancellor to initiate a war with Serbia, to reinvigorate a fading Austro-Hungarian Empire; the second secret plan was that of the German Military leadership, to provoke a wider war with France and Russia. He thought that the German military leadership, in the midst of a European arms race, believed that they would be unable to further expand the German army without extending the officer corps beyond the traditional Prussian aristocracy. Rather than allowing that to happen, they manipulated Austria-Hungary into starting a war with Serbia in the expectation that Russia would intervene, giving Germany a pretext to launch what was in essence a preventive war. Part of his thesis is that the German military leadership were convinced that by 1916–18, Germany would be too weak to win a war with France, England and Russia. Notably, Fromkin suggests that part of the war plan was the exclusion of Kaiser Wilhelm II from knowledge of the events, because the Kaiser was regarded by the German General Staff as inclined to resolve crisis short of war. Fromkin also argues that in all countries, but particularly Germany and Austria documents were widely destroyed and forged to distort the origins of the war.

See also

- History of Europe

- History of the Balkans

- Causes of World War II

- European Civil War

- Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

References

- ^ Henig, Ruth B. (2002). The origins of the First World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26205-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lieven, D. C. B. (1983). Russia and the origins of the First World War. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-69608-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 260–62. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. p. 102. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 88–92. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Kaiser and His Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany by John C. G. Röhl; Translated byTerence F. Cole, Cambridge University Press; 288 pages. p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Röhl, John C G. 1914: Delusion or Design. Elek. pp. 29–32. ISBN 0236154664.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Howard, Michael “Europe on the Eve of the First World War’ pages 21-34 from The Outbreak of World War I edited by Holger Herwig, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997 page 26

- ^ a b c d e Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 124–25. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1966, p 398

- ^ a b c d Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 153–55. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Fischer, Fritz (1967). Germany's aims in the First World War. New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-393-05347-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 138–43. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fromkin, David Europe’s Last Summer, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 pages 144-145

- ^ a b c d e Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 147–55. ISBN 978-0375411564.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Van Evera, Stephen. "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War." (Summer 1984), p. 62.

- ^ Fischer, Fritz. "War of Illusions: German Policies from 1911 to 1914." trans. (1975), p. 69.

- ^ Sagan, Scott D. 1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability (1986)

- ^ Albertini (1965) page viii

- ^ * Fischer, Fritz Germany's Aims In the First World War, W. W. Norton; 1967 ISBN 0-393-05347-4

- ^ a b Ferguson, Niall The Pity of War Basic Books, 1999 ISBN 0-465-05712-8

- ^ Michael Balfour, The Kaiser and his Times, Houghton Mifflin (1964) p. 434

- ^ Owen, Robert Latham. The Russian Imperial Conspiracy, 1892-1914, A and C Boni, New York, 1927, pp 78-81

- ^ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Oxford University Press, London, 1953, Vol II, pg. 197

- ^ Owen, Robert Latham. The Russian Imperial Conspiracy, 1892-1914, A and C Boni, New York, 1927, pp 93

- ^ Wank, Soloman (1997). "The Habsburg Empire". In Karen Barkey and Mark von Hagen (ed.). After Empire: Multiethnic Societies and Nation-Building. Oxford: Oxford Univesity Press.

- ^ Garland, John (1997). "The Strenth of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1914 (Part 1)". New Perspective.

- ^ Williamson, Samuel R. (1991). Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. p. 15. ISBN ISBN 0-312-05239-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Bridge, F.R. (2002). "The Foreign Policy of the Monarchy". In Mark Cornwall (ed.). The Last years of Austria-Hungary. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. p. 26.

- ^ Fellner, Fritz (1995). "Austria-Hungary". In Keith Wilson (ed.). Decisions for War. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ a b Leslie, John (1993). Elisabeth Springer and Leopold Kammerhofer (ed.). "The Antecedents of Austria-Hungary's War Aims". Wiener Beiträge zur Geschichte der Neuzeit. 20: 307–394.

- ^ Sked, Alan (1989). The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire 1815-1918. Burnt Mill: Longman Group. p. 254.

- ^ Williamson, Samuel R. (1991). Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-05239-1.

- ^ Bukharin, N., (1972), Imperialism and World Economy, (London).

- ^ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Oxford University Press, London, 1953, Vol II pp 461-462, 465

- ^ The Treaty of Alliance Between Germany and Turkey August 2, 1914

- ^ a b Taylor, A. J. P. (1954). The Struggle For Mastery In Europe 1848-1918. Oxford University Press. p. 524. ISBN 0-19-881270-1.

- ^ Ferguson 1999, p. 82.

- ^ Ferguson 1999, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Lambert, Nicholas A. "British Naval Policy, 1913-1914: Financial Limitation and Strategic Revolution" The Journal of Modern History, 67, no.3 (1995), pages 623-626.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara (1962). The Guns of August. New York: Random House.

- ^ Taylor, A. J. P. "War by Timetable: How the First World War Began" (London, 1969)