Clarence Thomas: Difference between revisions

m spacing |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Judge |

{{Infobox Judge |

||

|name = |

|name = George cloney |

||

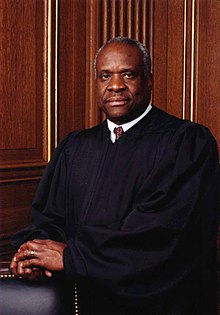

|image = Clarence Thomas official.jpg |

|image = Clarence Thomas official.jpg |

||

|imagesize = |

|imagesize = |

||

Revision as of 15:18, 4 February 2010

George cloney | |

|---|---|

Clarence Thomas | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Assumed office October 18, 1991[1] | |

| Nominated by | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Thurgood Marshall |

| Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit | |

| In office 1990–1991 | |

| Nominated by | George H.W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Robert Bork |

| Succeeded by | Judith Ann Wilson Rogers |

| 8th Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [2] | |

| In office 1982–1990 | |

| Preceded by | Eleanor Holmes Norton |

| Succeeded by | Evan J. Kemp, Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | Kate Ambush Thomas (divorced) Virginia Lamp Thomas |

| Children | Jamal Adeen Thomas |

| Alma mater | College of the Holy Cross Yale Law School |

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who has served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States since 1991. Thomas is the second African-American to serve on the Court, after Thurgood Marshall, whom he succeeded.

Thomas grew up in Georgia and was educated at the College of the Holy Cross and at Yale Law School. In 1974, he was appointed an Assistant Attorney General in Missouri and subsequently practiced law there in the private sector. In 1979, he became a legislative assistant to Missouri Senator John Danforth and in 1981 was appointed Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education. In 1982, Thomas was appointed Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and served in that position until 1990, when President George H. W. Bush nominated him for a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

After one year of service on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, Bush nominated Thomas to fill the seat on the United States Supreme Court being vacated by Thurgood Marshall. Thomas's confirmation hearings were bitter and intensely fought, centering around accusations that he had sexually harassed a subordinate at the EEOC, attorney Anita Hill. Thomas was ultimately confirmed by a vote of 52–48, the narrowest Supreme Court confirmation vote of the 20th century.[4]

Since joining the Court, Thomas has taken a textualist approach to judging, seeking to uphold what he sees as the original meaning of the United States Constitution and statutes. He is generally viewed as among the most conservative members of the Court. Thomas has often approached federalism issues in a way that limits the power of the federal government and expands power of state and local governments. At the same time, Thomas' opinions have generally supported a strong executive branch within the federal government.

Early life and education

Clarence Thomas was born in Pin Point, Georgia, a small, impoverished African-American community, which had no sewage system or paved roads. He was the second of three children born to M.C. Thomas, a farm worker, and Leola Williams, a domestic worker,[5][6] and is a descendant of American slaves. M.C. Thomas left his family when Thomas was two years old. Thomas' mother worked hard but was sometimes paid only pennies per day. She had difficulty putting food on the table and was forced to rely on charity.[7] After a house fire left them homeless, Thomas and his younger brother Myers were taken to Savannah, Georgia. (Thomas's sister Emma stayed behind with relatives in Pin Point).

When Thomas was seven, the family moved in with his maternal grandfather, Myers Anderson, and Anderson's wife, Christine (née Hargrove), in Savannah.[8] There, Thomas enjoyed indoor plumbing and regular meals for the first time in his life.[5] His grandfather, Myers Anderson, had little formal education, but had built a fuel oil business that also sold ice. Thomas calls his grandfather "the greatest man I have ever known."[8] When Thomas was 10, Anderson started taking the family to help at a farm every day from sunrise to sunset.[8] His grandfather believed in hard work and self-reliance; he would counsel Thomas to "never let the sun catch you in bed." Thomas's grandfather also impressed upon his grandsons the importance of getting a good education.[5]

Thomas was the only black person at his high school in Savannah, where he was an honor student.[9] Raised Roman Catholic (he later attended an Episcopal church with his wife but returned to the Catholic Church in the late 1990s). He considered entering the priesthood at the age of 16, becoming the first black student to attend St. John Vianney's Minor Seminary (Savannah) on the Isle of Hope.[8] He also briefly attended Conception Seminary College, a Roman Catholic seminary in Missouri. No one in Thomas's family had attended college and Thomas has said that during his first year in seminary he was one of only "three or four" blacks attending the school.[9] Thomas told interviewers that he left the seminary after overhearing a student say, in response to the shooting of Martin Luther King, Jr., "Good, I hope the son of a bitch died."[6][10] He did not think the church did enough to combat racism.[8]

At a nun's suggestion, Thomas attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where as a sophomore transfer student he had to adjust to a New England atmosphere very different from what he was used to in Savannah.[9] At Holy Cross, Thomas helped found the Black Student Union and once walked out after an incident in which black students were punished while white students were not for committing the same violation.[9] Some of the priests negotiated with the protesting black students to return to school,[9] and Thomas graduated in 1971 with an A.B. cum laude in English literature. Among Thomas's classmates at Holy Cross were future defense attorney Ted Wells and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Edward P. Jones.[11]

Thomas had a series of deferments from the military draft while in college at Holy Cross. Upon graduation, he was classified as 1-A and received a low lottery number, indicating that he might be drafted to serve in Vietnam. But Thomas failed his medical exam, reportedly due to curvature of the spine, and was not drafted.[12] Thomas then entered Yale Law School, from which he received a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree in 1974, graduating towards the middle of his class.[13]

Thomas has recollected that his Yale law degree was not taken seriously by law firms to which he applied after graduating, and potential employers assumed he obtained it because of affirmative action policies.[14] According to Thomas, he was "asked pointed questions, unsubtly suggesting that they doubted I was as smart as my grades indicated."[15]

Influences

In 1975, when Thomas read Race and Economics by economist Thomas Sowell, he found an intellectual foundation for this philosophy.[7][16] The book criticized social reforms by government and instead argued for individual action to overcome circumstances and adversity. He was also influenced by Ayn Rand,[17] particularly The Fountainhead, and would later require his staffers to watch the 1949 film version.[7] Thomas later said that novelist Richard Wright had been the most influential writer in his life; Wright's books Native Son and Black Boy "capture[d] a lot of the feelings that I had inside that you learn how to repress."[18]

Personal life

Thomas has one child, Jamal Adeen, from his first marriage. This marriage, to college sweetheart Kathy Grace Ambush, lasted from 1971 until their 1981 separation and 1984 divorce.[18][19] In 1987, Thomas married Virginia Lamp, a lobbyist, aide to Congressman Dick Armey, and subsequently an executive director at the conservative Heritage Foundation.[20] In 1997 they took in one of Thomas' great nephews.[21]

Since joining the Supreme Court, Thomas requested an annulment of his first marriage from the Roman Catholic Church, which was granted. He was reconciled to the Church in the mid-1990s and remains a practicing Catholic,[22][23] although he criticized the Church in his 2007 autobiography for its approach to racism in the 1960s, saying it was not as "adamant about ending racism then as it is about ending abortion now."[24] Thomas is one of thirteen Catholic justices—out of 110 justices total—in the history of the Supreme Court, and one of six currently on the Court.[25]

In 1994, Thomas performed the wedding ceremony for radio host Rush Limbaugh and his wife, Marta Fitzgerald.[26]

Career

Early career

From 1974 to 1977, Thomas was an Assistant Attorney General of Missouri under then State Attorney General John Danforth. When Danforth was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1976 to 1979, Thomas left to become an attorney with Monsanto Company in St. Louis, Missouri. He moved to Washington, D.C. and returned to work for Danforth from 1979 to 1981 as a Legislative Assistant. Both men shared a common bond in that both had studied to be ordained (although in different denominations). Danforth was to be instrumental in championing Thomas for the Supreme Court.

In 1981, he joined the Reagan administration. From 1981 to 1982, he served as Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office of Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. From 1982 to 1990 he was Chairman of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC"). Newsweek characterized Thomas as "openly ambitious for higher office" during his tenure at the EEOC. As Chairman, he promoted a doctrine of self-reliance, and halted the usual EEOC approach of filing class-action discrimination lawsuits, instead pursuing specific acts of individual discrimination.[27] He also asserted in 1984 that black leaders were "watching the destruction of our race" as they "bitch, bitch, bitch" about President Reagan instead of working with the Reagan administration to alleviate teenage pregnancy, unemployment and illiteracy.[28]

Federal judge

In June 1989, President George H. W. Bush appointed Thomas to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, despite Thomas's initial protestations that he would not like to be a judge.[29] Thomas gained the support of other African-Americans such as former Transportation Secretary William Coleman, but said that when meeting white Democratic staffers in the United States Senate, he was "struck by how easy it had become for sanctimonious whites to accuse a black man of not caring about civil rights."[29]

Thomas's confirmation hearing was uneventful,[30] and he developed warm relationships during his 19 months on the federal court, including with fellow federal judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[29][31]

Supreme Court nomination and confirmation

When Justice William Brennan stepped down in 1990, Bush wanted to nominate Thomas as Brennan's replacement; since he felt that replacing Marshall (who was expected to be retiring soon; leaving another open seat on the Court) with Thomas could imply that he received the appointment out of tokenism, but Bush then decided that Thomas had not yet had enough experience as a judge after only months on the federal bench.[29] Bush therefore nominated Judge David Souter of the First Circuit instead.[29]

After the appointment of David Souter and the ensuing disappointment of conservatives, White House chief of staff John H. Sununu promised that the president would fill the next Supreme Court vacancy with a "true conservative" and Sununu predicted a "knock-down, drag-out, bloody-knuckles, grass-roots fight" over confirmation.[32][33] On July 1, 1991 President Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to replace Thurgood Marshall, who had recently announced his retirement.[34] Marshall had been the only African-American justice on the Court. Legal author Jeffrey Toobin says Bush and others saw Thomas as "pretty much" the only qualified black candidate who would be a reliable conservative vote.[35]

President Bush said that Thomas was the "best qualified [nominee] at this time."[29] The American Bar Association's Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary rated Thomas "qualified" by a vote of 13 to 2.[36] Reagan nominee Robert Bork received twice as many “not qualified” votes as Thomas, and several nominees of Richard Nixon were rated as “not qualified” by a majority of that ABA committee.[37] However, the ABA rating of Thomas was the least favorable of any confirmed Supreme Court nominee dating back to the Eisenhower administration (most nominees receive unanimous "well qualified" evaluations).[36] Thomas had never argued a case in the high courts, though others have also been appointed without Supreme Court oral argument experience,[38] and prior to Thomas, forty Supreme Court justices had been appointed without any prior judicial service (though none have since).[39] Thomas had never written a legal book, article, or brief of any consequence, and had been a judge for only a year.[38]

Organizations including the NAACP, the Urban League and the National Organization for Women opposed the appointment based on Thomas's criticism of affirmative action and suspicions that Thomas might not be a supporter of the Supreme Court judgment in Roe v. Wade; NOW and the NAACP had also protested Bush's previous Court appointee, David Souter.[40] Under questioning during confirmation hearings, Thomas repeatedly asserted that he had not formulated a position on the Roe decision.[41]

Some of the public statements of Thomas's opponents foreshadowed the confirmation fight that would occur. One such statement came from activist Florynce Kennedy at a July 1991 conference of the National Organization for Women in New York City. Making reference to the failure of Ronald Reagan's nomination of Robert Bork, she said of Thomas, "We're going to 'bork' him."[42] The liberal campaign to defeat the Bork nomination served as a model for liberal interest groups opposing Thomas.[43] Likewise, in view of what had happened to Bork, Thomas's confirmation hearings were also approached as a political campaign by the White House and Senate Republicans.[44]

Clarence Thomas's formal confirmation hearings began on September 10, 1991.[35] Thomas was reticent when answering Senators' questions during the appointment process.[45] Four years earlier, Robert Bork, a law professor, had expounded on his judicial philosophy during his confirmation, and he had been refused confirmation.[38] Whereas Thomas' earlier writings had frequently referenced the legal theory of natural law, Thomas distanced himself from that controversial stance during his confirmation hearings, giving the impression that he had no views.[38][46][47] Thomas himself later asserted in his autobiography that in the course of his professional career, he had not developed a judicial philosophy.

Anita Hill allegations

Toward the end of the confirmation hearings, an FBI interview with Anita Hill was leaked. Hill, an attorney, had worked for Thomas at the Department of Education and the EEOC. After the leak, she was called to testify at Thomas's confirmation hearings, where she alleged that Thomas had subjected her to inappropriate comments of a sexual nature, stopping short of making a legal claim of sexual harassment, saying: "I did not bring the information forward to try to establish a legal claim for sexual harassment."[48] Hill's testimony included lurid details, and she was aggressively questioned by some Senators.[49]

Thomas denied the allegations, stating:

This is not an opportunity to talk about difficult matters privately or in a closed environment. This is a circus. It's a national disgrace. And from my standpoint, as a black American, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree.[50]

Hill was the only person to testify at the Senate hearings against Thomas. Angela Wright, who worked with Thomas at the EEOC before he fired her,[51] decided not to testify,[52] but alleged similar improprieties in a written statement, saying that Thomas had repeatedly made sexual comments to her, commenting on her body or pressuring her for dates.[53] {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)[10] Also, Sukari Hardnett, a former Thomas assistant, wrote to the Senate committee saying that although Thomas had not harassed her, "if you were young, black, female, reasonably attractive and worked directly for Clarence Thomas, you knew full well you were being inspected and auditioned as a female."[54][55]

Other former colleagues testified on Thomas's behalf. Nancy Altman, who shared an office with Thomas at the Department of Education, testified that she "could hear virtually every conversation for two years that Clarence Thomas had ... [and n]ot once in those two years did I ever hear Clarence Thomas make a sexist or offensive comment...." Altman said that it was "not credible that Clarence Thomas could have engaged in the kinds of behavior that Anita Hill alleges, without any of the women who he worked closest with—dozens of us, we could spend days having women come up, his secretaries, his chief of staff, his other assistants, his colleagues—without any of us having sensed, seen or heard something."[56] Senator Alan K. Simpson was puzzled about why Hill and Thomas met, dined, and spoke by phone on various occasions after they no longer worked together.[57]

According to the Oyez Project, there was a lack of convincing proof produced at the Senate hearings.[5] After extensive debate, the Judiciary Committee split 7–7 on September 27, sending the nomination to the full Senate without a recommendation. Thomas was confirmed by a 52–48 vote on October 15, 1991, the narrowest margin for approval in more than a century.[58] The final floor vote was mostly along party lines: 41 Republicans and 11 Democrats voted to confirm while 46 Democrats and two Republicans voted to reject the nomination.

Thomas' swearing-in was moved ahead of schedule and carried out informally, as the White House was concerned that additional stories about Thomas' private life might surface before he could be sworn in.[44] On October 23, 1991, Thomas took his seat as the 106th Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Shortly thereafter, the Washington Post received information potentially corroborating Hill's charges and contradicting some of Thomas' sworn testimony; however, as had already become a sitting Supreme Court Justice, the paper's editors decided not to proceed with additional investigation and reporting on the subject.[44]

The debate over who was telling the truth continues, and several books have been written about the original hearings and testimony that could have been presented. Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill have both written autobiographies that include their takes on the hearings. The conduct, meaning, and outcome of the hearings are still vigorously disputed by all sides.

Early years on the Court

Upon his appointment, Thomas was generally perceived as joining the conservative wing of the Court, voting most frequently with Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Scalia.[59] Though Thomas was immediately welcomed by most Justices, including Marshall, whom he was replacing, law clerks of some liberal justices viewed Thomas with contempt, questioning his qualifications and intellectual heft.[60] Legal reporter Jan Crawford Greenburg says that pundits' portrayal of Thomas as Antonin Scalia's understudy was grossly inaccurate - she says that from early on, it was more often Scalia changing his mind to agree with Thomas, rather than the other way around.[61][62] On the other hand, Greenburg suggests that the forcefulness of Thomas's views pushed Justices Souter, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Anthony Kennedy away.[61]

Judicial philosophy

Conservatism and originalism

Justice Thomas is often described as an originalist, as well as a member of the "far right" of the Supreme Court.[5][63][64] He is often described as the most conservative member of the Supreme Court,[13][65][66] although others give Justice Scalia that designation.[67][68][69] Scalia himself, contrasting his own judicial philosophy to Thomas' in 2005, said: "I am an originalist, but I am not a nut."[70]

Justice Thomas also acknowledges having some "libertarian leanings."[71]

Voting alignment

On average, from 1994 to 2004, Justices Scalia and Thomas had an 86.7% voting alignment, the highest on the Court, followed by Ginsburg and Souter (85.6%).[72] Scalia and Thomas's agreement rate peaked in 1996, at 97.7%.[72] More recently, in a given year, other pairs of justices have had alignments closer than Scalia and Thomas.[73]

The conventional wisdom that Thomas's votes follow Antonin Scalia's is reflected by Linda Greenhouse's observation that Thomas voted with Scalia 91 percent of the time during October Term 2006, and with Justice John Paul Stevens the least, 36% of the time.[74] Statistics compiled annually by Tom Goldstein of SCOTUSblog demonstrate that Greenhouse's count is methodology-specific, counting non-unanimous cases where Scalia and Thomas voted for the same litigant, regardless of whether they got there by the same reasoning.[75] Goldstein's statistics show that the two agreed in full only 74% of the time, and that the frequency of agreement between Scalia and Thomas is not as outstanding as is often implied by pieces aimed at lay audiences. For example, in that same term, Justices Souter and Ginsburg voted together 81% of the time by the method of counting that yields a 74% agreement between Thomas and Scalia; by the metric that produces the 91% Scalia/Thomas figure, Justices Ginsburg and Breyer agreed 90% of the time, and Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito agreed 94% of the time.[76]

Legal correspondent Jan Crawford Greenburg wrote in her book on the Supreme Court that Justice Thomas's forceful views moved moderates like Sandra Day O'Connor further to the left, but frequently attracted votes from former Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Scalia.[77] Mark Tushnet and Jeffrey Toobin both observe that Rehnquist rarely assigned important majority opinions to Thomas, because the latter's views made it difficult for him to persuade a majority of justices to join him.[78]

Number of dissenting opinions

From 1994 to 2004, on average, Justice Thomas was the third most frequent dissenter on the Court, behind Justices Stevens and Scalia.[72] Four other justices dissented as frequently in 2007.[79] Three other justices dissented as frequently in 2006.[80] One other justice dissented as frequently in 2005.[81]

Stare decisis

According to law professor Michael J. Gerhardt, Thomas has supported leaving a broad spectrum of constitutional decisions intact.[82] Justice Thomas supports statutory stare decisis.[83] During his confirmation hearings Thomas said: "[S]tare decisis provides continuity to our system, it provides predictability, and in our process of case-by-case decision making, I think it is a very important and critical concept."[84] Among the thirteen justices who served on the Rehnquist Court, Thomas ranked eleventh for the number of votes he cast overturning precedent (without accounting for length of Court service).[85] However, on a frequency basis, he urged overruling and joined in overruling precedents more frequently than any other justice.[85]

According to Justice Scalia, Justice Thomas is more willing to overrule constitutional cases: "If a constitutional line of authority is wrong, he would say let's get it right. I wouldn't do that."[86] Thomas's belief in originalism is strong; he has said, "When faced with a clash of constitutional principle and a line of unreasoned cases wholly divorced from the text, history, and structure of our founding document, we should not hesitate to resolve the tension in favor of the Constitution's original meaning."[87] Thomas believes that an erroneous decision can and should be overturned, no matter how old it is.[87]

Commerce Clause

Justice Thomas has consistently supported narrowing the Court's interpretation of the Constitution's Interstate Commerce Clause (which is often simply called the "Commerce Clause") so as to limit federal power and allow states more power to regulate intrastate commerce. At the same time, Thomas has broadly interpreted states' sovereign immunity from lawsuits under the Commerce Clause.[88]

In both United States v. Lopez and United States v. Morrison, the Court held that Congress lacked power under the Commerce Clause to regulate non-commercial activities. In both of those cases, Thomas wrote a separate concurring opinion arguing for the original meaning of the Commerce Clause. Subsequently, in Gonzales v. Raich, the Court interpreted the Interstate Commerce Clause combined with the Necessary and Proper Clause so as to empower the federal government to arrest, prosecute, and imprison patients who used marijuana grown at home for medicinal purposes. Thomas dissented in Raich, again arguing for the original meaning of the Commerce Clause.

Both Justices Thomas and Scalia have rejected the notion of a Dormant Commerce Clause, also known as the “Negative Commerce Clause.” That doctrine bars state commercial regulation even if Congress has not yet acted on the matter.[89]

In Lopez, Thomas expressed his view that any federal regulation of either manufacturing or agriculture is unconstitutional; he sees both as outside the scope of the Commerce Clause.[90][91] He believes federal legislators have overextended the Commerce Clause, while some of his critics argue that Thomas’s position about Congressional authority would invalidate much of the contemporary work of the federal government.[91] According to Justice Thomas, it is not the Court's job to update the Constitution, whereas proponents of broad national power such as Professor Michael Dorf deny that they are trying to update the Constitution, and instead say they are merely addressing a set of economic facts that did not exist when the Constitution was framed.[92]

Federalism

Federalism was a central part of the Rehnquist Court's constitutional agenda.[93] Justice Thomas consistently voted for outcomes that promoted state-governmental authority, in cases involving federalism-based limits on Congress’s enumerated powers.[93] According to law professor Ann Althouse, the Court has yet to move toward "the broader, more principled version of federalism propounded by Justice Thomas."[94]

In Foucha v. Louisiana, Justice Thomas dissented from the majority opinion which required the removal from a mental institution of a prisoner who had become sane.[95] The Court held that a Louisiana statute violated the Due Process Clause "because it allows an insanity acquittee to be committed to a mental institution until he is able to demonstrate that he is not dangerous to himself and others, even though he does not suffer from any mental illness."[96] Dissenting, Thomas cast the issue as a matter of federalism.[95] "Removing sane insanity acquittees from mental institutions may make eminent sense as a policy matter," he concluded, "but the Due Process Clause does not require the States to conform to the policy preferences of federal judges."[96]

Executive power

Thomas has argued that the executive branch has broad authority under the Constitution and federal statutes. In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, he was the only justice who agreed with the Fourth Circuit that Congress had power to authorize the President's detention of US citizens who are enemy combatants. Thomas granted the federal government the "strongest presumptions" and said "due process requires nothing more than a good-faith executive determination" to justify the imprisonment of Hamdi, a US citizen.[97]

Thomas also was one of three justices who dissented in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which held that the military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay required explicit congressional authorization, and held that the commissions conflicted with both the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) and "at least" Common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention.[98] Thomas argued that Hamdan was an illegal combatant and therefore not protected by the Geneva Convention, and he also agreed with Justice Scalia that the Court was "patently erroneous" in its declaration of jurisdiction in this case.

Free speech

Among the nine justices, Thomas was the second most likely to uphold free speech claims (tied with David Souter), as of 2002.[99] He has voted in favor of First Amendment claims in cases involving a wide variety of issues, including pornography, campaign contributions, political leafletting, religious speech, and commercial speech.

On occasion, however, he has disagreed with free speech claimants. For example, he dissented in Virginia v. Black, a case that struck down a Virginia statute that banned cross-burning. Concurring in Morse v. Frederick, he argued that students' free speech rights in public schools are limited.[100]

Thomas authored the decision in ACLU v. Ashcroft, which held that the Child Online Protection Act might (or might not) be constitutional. The government was enjoined from enforcing it, pending further proceedings in the lower courts.[101]

Fourth Amendment

In cases regarding the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, Thomas often favors police over defendants. For example, his opinion for the Court in Board of Education v. Earls upheld drug testing for students involved in extracurricular activities, and he wrote again for the Court in Samson v. California, permitting random searches on parolees. He dissented in the case Georgia v. Randolph, which prohibited warrantless searches that one resident approves and the other opposes, arguing that the case was controlled by the Court's decision in Coolidge v. New Hampshire. In Indianapolis v. Edmond, Thomas described the Court's extant case law as having held that "suspicionless roadblock seizures are constitutionally permissible if conducted according to a plan that limits the discretion of the officers conducting the stops." Although he expressed doubt that those cases were correctly decided, he concluded that since the litigants in the case at bar had not briefed or argued that the earlier cases be overruled, he believed that the Court should assume their validity and rule accordingly.[102] There are counterexamples, however: he was in the majority in Kyllo v. United States, which held that the use of thermal imaging technology to probe a suspect's home, without a warrant, violated the Fourth Amendment.

In cases involving schools, Thomas has advocated greater respect for the doctrine of in loco parentis, which he defines as "parents delegat[ing] to teachers their authority to discipline and maintain order."[103] His dissent in Safford Unified School District v. Redding illustrates his application of this postulate in the Fourth Amendment context. School officials in the Safford case had a reasonable suspicion that 13-year-old Savana Reading was illegally distributing prescription-only drugs. All of the justices concurred that it was therefore reasonable for the school officials to search Ms. Reading, and the main issue before the Court was only whether the search went too far by becoming a strip search or the like.[103] All justices but Thomas concluded that this search violated the Fourth Amendment. The majority required a finding of danger or reason to believe drugs were hidden in a student's underwear in order to justify a strip search. In contrast, Thomas said, "It is a mistake for judges to assume the responsibility for deciding which school rules are important enough to allow for invasive searches and which rules are not”[104] and that "reasonable suspicion that Redding was in possession of drugs in violation of these policies, therefore, justified a search extending to any area where small pills could be concealed." Thomas said, "There can be no doubt that a parent would have had the authority to conduct the search."[103]

Eighth Amendment and capital punishment

Justice Thomas was among the dissenters in both Atkins v. Virginia and Roper v. Simmons, which held that the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the application of the death penalty to certain classes of persons. In Kansas v. Marsh, his opinion for the Court indicated a belief that the Constitution affords states broad procedural latitude in imposing the death penalty, provided they remain within the limits of Furman v. Georgia and Gregg v. Georgia, the 1976 case in which the Court had reversed its 1972 ban on death sentences as long as states followed certain procedural guidelines.

In Hudson v. McMillian, a prisoner had been beaten, garnering a cracked lip, broken dental plate, loosened teeth, and cuts and bruises. Although these were not "serious injuries," the Court believed, it held that "[t]he use of excessive physical force against a prisoner may constitute cruel and unusual punishment even though the inmate does not suffer serious injury."[105] Dissenting, Thomas wrote that, in his view, "a use of force that causes only insignificant harm to a prisoner may be immoral, it may be tortious, it may be criminal, and it may even be remediable under other provisions of the Federal Constitution, but it is not 'cruel and unusual punishment.' In concluding to the contrary, the Court today goes far beyond our precedents.”[105] Thomas's vote - in one of his first cases after joining the Court - was an early example of his willingness to be the sole dissenter (Scalia later joined the opinion).[106] Thomas' opinion was criticized by the 7-member majority of the Court, which wrote that by comparing physical assault to other prison conditions such as poor prison food, Thomas' opinion ignored "the concepts of dignity, civilized standards, humanity, and decency that animate the Eighth Amendment."[105] According to historian David Garrow, Thomas's dissent in Hudson was a "classic call for federal judicial restraint, reminiscent of views that were held by Felix Frankfurter and John M. Harlan II a generation earlier, but editorial criticism rained down on him."[107] Thomas would later respond to the accusation "that I supported the beating of prisoners in that case. Well, one must either be illiterate or fraught with malice to reach that conclusion....no honest reading can reach such a conclusion."[107]

In Doggett v. United States, the defendant had been a fugitive since his indictment in 1980. After he was arrested in 1988, the Court held that the 8½ year delay between indictment and arrest violated Doggett's Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial.[108] Thomas dissented, arguing that the purpose of the Speedy Trial Clause was to prevent "'undue and oppressive incarceration' and the 'anxiety and concern accompanying public accusation'" and that the case implicated neither.[108] He cast the case as instead "present[ing] the question [of] whether, independent of these core concerns, the Speedy Trial Clause protects an accused from two additional harms: (1) prejudice to his ability to defend himself caused by the passage of time; and (2) disruption of his life years after the alleged commission of his crime." Thomas dissented from the Court's decision to, as he saw it, answer the former in the affirmative.[108] Thomas wrote that dismissing the conviction "invites the Nation's judges to indulge in ad hoc and result-driven second guessing of the government's investigatory efforts. Our Constitution neither contemplates nor tolerates such a role."[109]

In United States v. Bajakajian, Thomas joined with the Court's more liberal bloc to write the majority opinion declaring a fine unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. The fine was for failing to declare over $300,000 in a suitcase on an international flight. Under a federal statute, 18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(1), the passenger would have had to forfeit the entire amount. Thomas noted that the case required a distinction to be made between civil forfeiture and a fine exacted with the intention of punishing the respondent. He found that the forfeiture in this case was clearly intended as a punishment at least in part, was "grossly disproportional," and a violation of the Excessive Fines Clause.[110]

Church and state

Law professor and former Thomas clerk John Yoo says Justice Thomas supports allowing religious groups more participation in public life.[111] Thomas says the Establishment Clause ("Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion") "is best understood as a federalism provision –- it protects state establishments from federal interference but does not protect any individual right."[112]

In Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow[112] and Cutter v. Wilkinson,[113] Thomas wrote that he supported incorporation of the Free Exercise Clause, which he says "clearly protects an individual right." He said that any law that would violate the Establishment Clause might also violate the Free Exercise Clause.

Thomas says "it makes little sense to incorporate the Establishment Clause" vis-à-vis the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.[112] And in Cutter, he wrote: "The text and history of the Clause may well support the view that the Clause is not incorporated against the States precisely because the Clause shielded state establishments from congressional interference."

Equal protection

Thomas believes that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids any consideration of race, such as race-based affirmative action or preferential treatment. In Adarand Constructors v. Pena, for example, he wrote that "there is a 'moral [and] constitutional equivalence' between laws designed to subjugate a race and those that distribute benefits on the basis of race in order to foster some current notion of equality. Government cannot make us equal; it can only recognize, respect, and protect us as equal before the law. That [affirmative action] programs may have been motivated, in part, by good intentions cannot provide refuge from the principle that under our Constitution, the government may not make distinctions on the basis of race."[114]

In Gratz v. Bollinger, Thomas said that, in his view, "a State’s use of racial discrimination in higher education admissions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause."[115] In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, Thomas joined the opinion of Chief Justice Roberts, who concluded that "[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race."[116] Concurring, Thomas wrote that "if our history has taught us anything, it has taught us to beware of elites bearing racial theories," and charged that the dissent carried "similarities" to the arguments of the segregationist litigants in Brown v. Board of Education.[116] And in Grutter v. Bollinger, he approvingly quoted Justice Harlan's Plessy v. Ferguson dissent: “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”[117]

Abortion

Justice Thomas supports ending constitutional protections for abortion.[111] In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Court reaffirmed Roe v. Wade. Thomas along with Justice Byron White joined the dissenting opinions of Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia. Rehnquist wrote that "[w]e believe Roe was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases."[118] Scalia's opinion concluded that the right to obtain an abortion is not "a liberty protected by the Constitution of the United States."[118] "[T]he Constitution says absolutely nothing about it," Scalia wrote, "and [ ] the longstanding traditions of American society have permitted it to be legally proscribed."[118]

In Stenberg v. Carhart (2000) the Court struck down a state ban on partial-birth abortion, concluding that it failed the "undue burden" test established in Casey. Thomas dissented, writing: "Although a State may permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do so."[119] He went on to criticize the reasoning of the Casey and Stenberg majorities: "The majority’s insistence on a health exception is a fig leaf barely covering its hostility to any abortion regulation by the States -- a hostility that Casey purported to reject."

In Gonzales v. Carhart (2007), the Court rejected a facial challenge to a federal ban on partial-birth abortion.[120] Concurring, Thomas asserted that the Court's abortion jurisprudence had no basis in the Constitution, but that the Court had accurately applied that jurisprudence in rejecting the challenge.[120] Thomas added that the Court was not deciding the question of whether Congress had the power to outlaw partial birth abortions: [W]hether the Act constitutes a permissible exercise of Congress’ power under the Commerce Clause is not before the Court [in this case]....[T]he parties did not raise or brief that issue; it is outside the question presented; and the lower courts did not address it."[120]

Gay Rights

In Lawrence v. Texas (2004), Thomas issued a one page dissent where he called the Texas anti-gay sodomy statute "silly." He then said that if he were a member of the Texas legislature he would vote to repeal the law. But since he was not a member of the state legislature, but instead a federal judge, and the Due Process Clause did not (in his view) touch on the subject, he could not vote to strike it down. Accordingly, Justice Thomas saw the issue as a matter for the states to decide on their own.

Judicial review

Justice Thomas is the justice most willing to exercise judicial review. According to a New York Times editorial, “from 1994 to 2005....Justice Thomas voted to overturn federal laws in 34 cases and Justice Scalia in 31, compared with just 15 for Justice Stephen Breyer."[121]

In 2009's Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, Thomas was the sole dissenter, voting in favor of throwing out Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Section 5 requires states with a history of racial voter discrimination—mostly states from the old South—to get Justice Department clearance when revising election procedures. Though Congress had reauthorized Section 5 in 2006 for another 25 years, Thomas said the law was no longer necessary, pointing out that the rate of black voting in seven Section 5 states was higher than the national average. Thomas said "the violence, intimidation and subterfuge that led Congress to pass Section 5 and this court to uphold it no longer remains."[122]

Approach to oral arguments

Thomas is well-known for his reticence during the Court's oral arguments. In 2009, the New York Times noted that he had not asked a question from the bench in over 3 years.[123] Thomas gave some reasons during a question-and-answer session with high school students in 2000:

I have some very active colleagues who like to ask questions. Usually, if you wait long enough, someone will ask your question. The other thing, I was on that other side of the podium before, in my earlier life, and it's hard to stand up by yourself and to have judges who are going to rule on your case ask you tough questions. I don't want to give them a hard time.

In November 2007, Thomas said to an audience at Hillsdale College in Michigan: "My colleagues should shut up!" He later explained, "I don't think that for judging, and for what we are doing, all those questions are necessary."[124] Thomas is not the first quiet justice; in the 1970s and 1980s, justices such as William J. Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and Harry Blackmun were likewise generally quiet.[125][126] However, Thomas' silence stood out on the Court of the 1990s, on which the other eight justices engaged in active questioning during oral arguments.[126]

Thomas attributes his listening habit partly to his cultural environment; he spent his earliest years in the Gullah/Geechee cultural region of coastal Georgia and grew up speaking the Gullah language, a creole based on English and various West African languages.[127] Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson says that Thomas "erased his accent long ago" and therefore this cannot be an explanation for his silence from the bench.[128] CNN analyst Jeffrey Toobin also questions Thomas's explanation, writing that Thomas knew how to speak English well from an early age, because he lived with his English-speaking grandfather from the age of six, attended only English-speaking parochial schools, and earned excellent school grades.[129]

Public perception

Thomas has rarely given media interviews during his time on the Court. He said in 2007: "One of the reasons I don't do media interviews is, in the past, the media often has its own script."[9] In 2007, Justice Thomas received a $1.5 million advance for writing his memoir, My Grandfather's Son.[24] It became a bestseller.[130]

Writings

- Thomas, Clarence (2007). My Grandfather's Son: A Memoir, Harper, ISBN 0-06-056555-1.

- Thomas, Clarence. "Why Federalism Matters," Drake Law Review, Volume 48, Issue 2, page 234 (2000).

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by court composition

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by education

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by time in office

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Roman Catholic United States Supreme Court justices.

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Roberts Court

Footnotes and references

- ^ "Federal Judicial Center: Clarence Thomas". 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Biography, Clarence Thomas

- ^ Clarence Thomas bio from Notable Names Database

- ^ www.BlackPast.org, Online Reference Guide to African American History

- ^ a b c d e Oyez, The Oyez Project Supreme Court media, Clarence Thomas biography (2003).

- ^ a b Brady, Diane (2007-03-12). "The Holy Cross Fraternity". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ a b c Merida, Kevin; Fletcher, Michael A. (August 4, 2002), "Supreme Discomfort", Washington Post Magazine, pp. W08

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e Dolin, Monica (2007-10-03). "Anger Still Fresh in Clarence Thomas' Memoir". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ a b c d e f Brady, Diane. "Clarence Thomas Speaks Out", BusinessWeek (2007-03-12).

- ^ a b Margolick, David (1991-07-03). "Judge Portrayed as a Product Of Ideals Clashing With Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-19. Cite error: The named reference "nytimes" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Weeks, Linton (2007-02-21). "Ted Wells, Center Of the Defense". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Simon, Martin (September 16, 1991). "Supreme Mystery". Newsweek. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ a b Kroft, Steve, (Sept. 30, 2007) Clarence Thomas: The Justice Nobody Knows -- Supreme Court Justice Gives First Television Interview To 60 Minutes.

- ^ "Talk Radio Online::Radio Show". Townhall.com. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Lithwick, Dahlia. "From Clarence Thomas to Palin" (Opinion Column), Newsweek (2008-09-27).

- ^ Tumulty, Karen (1991-07-07). "Court Path Started in the Ashes: A fire launched Clarence Thomas on a path toward fierce personal drive-but not before the Supreme Court nominee journeyed through anger, self-hatred, confusion and doubt". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Bidinotto, Robert James,Celebrity "Rand Fans" — Clarence Thomas,, The Atlas Society.

- ^ a b Greenburg, Jan Crawford (2007-09-30). "Clarence Thomas: A Silent Justice Speaks Out: Part VII: 'Traitorous' Adversaries: Anita Hill and the Senate Democrats". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ Merida, Kevin (April 22, 2007). "Justice Thomas's Life A Tangle of Poverty, Privilege and Race". Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Toobin, Jeffrey (2007). The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-51640-2.

- ^ "Justice Thomas marches to own tune," Associated Press via USA Today (2001-09-03).

- ^ "Insight Scoop | The Ignatius Press Blog: Did Clarence Thomas just say he's not Catholic?". Insightscoop.typepad.com. 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ "The religion of Clarence Thomas, Supreme Court Justice". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ a b Robert Barnes, Michael A. Fletcher and Kevin Merida (2007-09-29). "Justice Thomas Lashes Out in Memoir". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after his retirement. James F. Byrnes was raised as Catholic, but converted to Episcopalianism before his confirmation as a Supreme Court Justice.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (May 30, 1994). "Wedding Announcements". New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ Thomas, Evan (July 15, 1991). "Where Does He Stand?". Newsweek. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ Williams, Juan (October 25, 1984). "EEOC Chairman Blasts Black Leaders". Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

The chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission says that black leaders are 'watching the destruction of our race' as they 'bitch, bitch, bitch' about President Reagan but fail to work with the administration to solve problems. Clarence Thomas said in an interview that, in his 3 1/2 years on the job, no major black leader has sought his help in influencing the Reagan administration. Black spokesmen should be working with the administration to solve such problems as teen-age pregnancy, unemployment or illiteracy instead of working against Reagan, Thomas said.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenburg, Jan Crawford (2007-09-30). "Clarence Thomas: A Silent Justice Speaks Out". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ The Library of Congress Presidential Nominations, Look up of Nomination: PN838-101. February 06, 1990 - Committee on Judiciary, hearings held. February 22, 1990 - Committee on Judiciary, ordered to be reported favorably, placed on Senate Executive Calendar. March 06, 1990 - floor action, confirmed by the Senate by voice vote.

- ^ Federal Judicial Center

- ^ Jefferson, Margo. “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; The Thomas-Hill Question, Answered Anew,” New York Times (1994-11-11).

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 21 (New York: Random House 2007). ISBN 9780739354599.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen. “The Supreme Court; Conservative Black Judge, Clarence Thomas, Is Named to Marshall’s Court Seat,” New York Times (1991-07-02).

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 30 (Random House 2007).

- ^ a b Merida, Kevin and Fletcher, Michael. Supreme Discomfort, page 398 (Random House 2008).

- ^ Hall, Kermit and McGuire, Kevin. The Judicial Branch, page 155 (Oxford University Press 2006).

- ^ a b c d Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 31 (Random House 2007).

- ^ "Supreme Court Justices Without Prior Judicial Experience Before Becoming Justices," Findlaw (c. 2009).

- ^ Yarbrough, Tinsley (2005). David Hackett Souter: Traditional Republican on the Rehnquist Court. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ It is routine for nominees, at all levels of the Federal judiciary, to refuse to discuss cases during their confirmation hearings that might come before them if they are confirmed. Clinton appointed Associate Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, who both refused to discuss Roe before the Judiciary Committee, even though Ginsburg has worked for years for the ACLU defending it. Despite this nearly universal refusal of nominees to discuss hot button issues such as Roe, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee nearly always try to draw the nominee's view out during confirmation hearings.

- ^ "The Borking Begins; Linda Chavez's mistake was she took a less fortunate person into her home" (Editorial), Wall Street Journal (2001-01-08).

- ^ Tushnet, Mark. A Court Divided, page 335 (Norton & Company 2005).

- ^ a b c Mayer, Jane (1994). Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-452-27499-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 25 (Random House 2007).

- ^ Woodward, Kenneth (September 23, 1991). "Natural Law, An Elusive Tradition". Newsweek. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ Epstein, Aaron (August 30, 1991). "The Natural Law According To Clarence Thomas". Seattle Times. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ “THE THOMAS NOMINATION; Excerpts From Senate's Hearings on the Thomas Nomination,” New York Times (1991-10-12): “SPECTER: So that you are not now drawing a conclusion that Judge Thomas sexually harassed you? MS. HILL: Yes, I am drawing that conclusion.”

- ^ In particular, the questioning by Senator Specter was intense. See Morrison, Toni. “Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power,” page 55 (Pantheon Books 1992). After the questioning, Specter said that, "the testimony of Professor Hill in the morning was flat out perjury", and that "she specifically changed it in the afternoon when confronted with the possibility of being contradicted." See transcript, page 230.

- ^ Hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library, October 11, 1991.

- ^ "The Thomas Nomination; On the Hearing Schedule: Eight Further Witnesses," The New York Times (1991-10-13)

- ^ See hearing record from October 13, 1991. Senator Biden wrote to Wright: "I wish to make clear, however, that if you want to testify at the hearing in person, I will honor that request." Wright responded to Biden: "I agree the admission of the transcript of my interview and that of Miss Jourdain's in the record without rebuttal at the hearing represents my position and is completely satisfactory to me."

- ^ "United States Senate, Transcript of Proceedings" (PDF). gpoaccess.gov. 1991-10-10. pp. 442–511. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Marcus, Ruth. "One Angry Man, Clarence Thomas Is No Victim" (Opinion Column) Washington Post (2007-10-30).

- ^ Press Release, FAIR's Reply to Limbaugh's Non-Response (10/17/94) Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

- ^ "Nomination of Judge Clarence Thomas to be Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States," Senate Hearing 102-1084, pt. 4, page 590. (See table of contents for hearing, here [1].)

- ^ “THE THOMAS NOMINATION; Questions to Those Who Corroborated Hill Account,” New York Times (1991-10-21).

- ^ Hall, Kermit (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, page 871, Oxford Press, 1992 ISBN 0195058356; ISBN 9780195058352.

- ^ Vanzo, John (October 12, 2007). "Clarence Thomas". Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, pp. 112-113 (Penguin Group 2007). ISBN 9781594201011

- ^ a b Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, pp. 115-116 (Penguin Group 2007).

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford (2007-01-28). "The Truth About Clarence Thomas". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Supreme Court Watch, Profile: Justice Clarence Thomas Public Broadcasting Service.

- ^ Cohen, Adam, Editorial Observer (June 3, 2007) New York Times.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 116 (Random House 2007).

- ^ Lazarus, Edward. “BOOK REVIEW - It seems Justice Thomas is still seeking confirmation - My Grandfather's Son A Memoir Clarence Thomas,” Los Angeles Times (2007-10-01).

- ^ Marshall, Thomas. Public Opinion and the Rehnquist Court, page 79 (SUNY Press, 2008).

- ^ Von Drehle, David. "Executive Branch Reined In", Washington Post (2004-06-29).

- ^ West, Paul. A president under siege throws down the gauntlet,” Hartford Courant (2005-11-01).

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey (2007). The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. Random House. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-385-51640-2.

- ^ Kauffman B., "Clarence Thomas", Reason Magazine, November 1987, Accessed May 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c “Nine Justices, Ten Years: A Statistical Retrospective,” Harvard Law Review, volume 118, page 510, 519 (2004). Cite error: The named reference "Harvard" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Baude, Will. Brothers in Law, The New Republic Online, (2004-06-30): "Justices Souter and Ginsburg were in complete agreement in 85 percent of the Court’s decisions. Chief Justice Rehnquist agreed with Justice O’Connor in 79 percent and Justice Kennedy in 77 percent. Justices Stevens and Souter agreed 77 percent of the time; so did Justices Ginsburg and Breyer. Thomas and Scalia agreed in only 73 percent of the cases. Thomas regularly breaks with Scalia, disagreeing on points of doctrine, finding a more measured and judicial tone, and calling for the elimination of bad law. Unless he is simply a very bad yes-man, Clarence Thomas is a more independent voice than most people give him credit for."

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. "In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court, Moved Right", The New York Times, July 1, 2007.

- ^ “SCOTUSblog Agreement Stats for OT06 … Non-Unanimous Cases”

- ^ “SCOTUSblog Agreement Stats for OT06….”

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, p. 166 (Penguin Group 2007).

- ^ Mark Tushnet, A Court Divided 85-6 (2006); Jeffrey Toobin, The Nine 119 (2008).

- ^ “The Statistics,” Harvard Law Review, volume 121, page 439 (2007).

- ^ “The Statistics,” Harvard Law Review, volume 120, page 372 (2006).

- ^ “The Statistics,” Harvard Law Review, volume 119, page 415 (2005).

- ^ Gerhardt, Michael. The Power of Precedent, page 188 (Oxford University Press 2008): Thomas "does not, at least statistically, urge more than three overrulings per term, thus indicating his willingness to leave a fairly broad spectrum of constitutional decisions intact".

- ^ Barrett, Amy. “Statutory Stare Decisis in the Courts of Appeals,” George Washington Law Review (2005).

- ^ "A Big Question About Clarence Thomas", The Washington Post, October 14, 2004. Accessed May 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Gerhardt, Michael. The Power of Precedent, pages 249 (ranked eleventh for overturning precedent) and 12 (most frequently urged overturning) (Oxford University Press 2008).

- ^ Ringel, Jonathan. “The Bombshell in the Clarence Thomas Biography”, Daily Report bvia Law.com (2004-08-05). Scalia also said that Thomas "doesn't believe in stare decisis, period."

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 120 (Random House 2007).

- ^ E.g., Seminole Tribe v. Florida 517 U.S. 44 (1996). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ United Haulers Assn. v. Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Mgmt. Auth. 550 U.S. 330 (2007). Full text opinion courtesy of Cornell University

- ^ United States v. Lopez 514 U.S. 549 (1995). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine. Page 100.

- ^ Dorf, Michael. “What California’s Trans Fat Ban Teaches Us About Federalism,” Findlaw’s Writ (2008-07-29): “Proponents of broad national power like myself do not say that the Court should update the Constitution to keep it in tune with the times. Rather, we argue —- or at least some of us argue —- that the growth of a national, indeed, global, economy, means that activities that might have been carried out in relatively discrete local markets in 1789 are now undoubtedly part of interstate and international commerce.”

- ^ a b Joondeph, Bradley “Federalism, the Rehnquist Court, and the Modern Republican Party,” Oregon Law Review, Volume 87 (2008): "Most scholars agree that federalism was central to the Rehnquist Court’s constitutional agenda."

- ^ Althouse, Ann. “Why Talking About States' Rights Cannot Avoid the Need for Normative Federalism Analysis: A Response to Professors Baker and Young,” Duke Law Journal, Volume 51, page 363 (2001).

- ^ a b Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, p. 117 (Penguin Group 2007).

- ^ a b Foucha v. Louisiana, 504 U.S. 71 (1992). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006).

- ^ Volokh, Eugene. "How the Justices Voted in Free Speech Cases, 1994-2000" (Updated), 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1191 (2001).

- ^ Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ American Civil Liberties Union v. Ashcroft, 535 U.S. 564 (2002), full text courtesy of Findlaw.

- ^ Indianapolis v. Edmond, 531 U.S. 32 (2000). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ a b c Safford Unified School District v. Redding, 557 U. S. __ (2009). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ “Court Says Strip Search of Ariz. Teenager Illegal,” Associated Press via NPR (2009-06-25).

- ^ a b c Hudson v. McMillian, 503 U.S. 1 (1992).

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, p. 119 (Penguin Group 2007).

- ^ a b Garrow, David. "Saving Thomas", The New Republic (2004-10-25).

- ^ a b c Doggett v. United States, 505 U.S. 647 (1992). Full text of opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, p. 123 (Penguin Group 2007).

- ^ United States v. Bajakajian, 524 U.S. 321 (1998).

- ^ a b Yoo, John, Opinion (October 9, 2007) The Real Clarence Thomas Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b c Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow, 542 U.S. 1 (2004). Thomas wrote: "It may well be the case that anything that would violate the incorporated Establishment Clause would actually violate the Free Exercise Clause, further calling into doubt the utility of incorporating the Establishment Clause."

- ^ Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005). Thomas wrote: "I note, however, that a state law that would violate the incorporated Establishment Clause might also violate the Free Exercise Clause."

- ^ Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, 515 U.S. 200 (1995).

- ^ Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003).

- ^ a b Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007).

- ^ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

- ^ a b c Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- ^ Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000).

- ^ a b c Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

- ^ “Activism Is in the Eye of the Ideologist” (Editorial), New York Times (2006-09-11).

- ^ Opinion of Thomas, J. NORTHWEST AUSTIN MUNICIPAL UTILITY DISTRICT NUMBER ONE v. ERIC H. HOLDER, Jr., ATTORNEY GENERAL (June 22, 2009) Full text courtesy of Cornell University Law School.

- ^ Bedard, Paul. "This Is Not Perry Mason," Washington Whispers, U.S. News & World Report (2007-11-29).

- ^ Garrow, David. "The Rehnquist Reins", New York Times Magazine (1996-10-06).

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey (2007). The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. Random House. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-385-51640-2.

- ^ "The 43rd President; In His Own Words," The New York Times (2000-12-14).

- ^ Patterson, Orlando. Thomas Agonistes (June 17, 2007). New York Times book review.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, p. 106 (Random House 2007).

- ^ Garner, Dwight. “TBR; TBR: Inside the List,” New York Times (2007-10-21).

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Brooks, Roy L. (2008) Structures of Judicial Decision Making from Legal Formalism to Critical Theory 2nd Ed., (Durham, N.C., (Carolina Academic Press), 308 pp. ISBN 1-59460-123-2; ISBN 978-1-59460-123-1.

- Carp, Dylan (1998, September). Out of Scalia's Shadow. Liberty.

- Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789-1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly Books, 2001) ISBN 1568021267; ISBN 9781568021263.

- Foskett, Ken (2004). Judging Thomas: The Life and Times of Clarence Thomas, William Morrow, ISBN 0-06-052721-8

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers, 1995) ISBN 0791013774, ISBN 978-0791013779.

- Gerber, Scott D. First Principles: The Jurisprudence of Clarence Thomas (January, 1999) New York University Press 281 pages, January 1999 ISBN 081473099X

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict (January, 2007). Penguin Group (USA) ISBN 9781594201011 368 pp.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0195058356; ISBN 9780195058352.

- Holzer, Henry Mark. Supreme Court Opinions of Clarence Thomas 1991-2006: A Conservative's Perspective (Hardcover) 332 pages Booklocker.com (February 28, 2006) ISBN 1591139112; ISBN 978-1591139119.

- Lazarus, Edward (2005, Jan. 6). Will Clarence Thomas Be the Court's Next Chief Justice? FindLaw.

- Mayer, Jane, and Jill Abramson (1994). Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas, Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-452-27499-0

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0871875543.

- Onwuachi-Willig, Angela (2005). Just Another Brother on the SCT?: What Justice Clarence Thomas Teaches Us About the Influence of Racial Identity. Iowa Law Review, 90.

- Presser, Stephen B. (2005, Jan.-Feb.) Touting Thomas: The Truth about America's Most Maligned Justice. Legal Affairs.

- Shils, Edward and Rheinstein, Max. (1964) Max Weber Law in Economy and Society, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) ISBN 0-674-55651-8; ISBN 0674556518; ISBN 9780674556515.

- Thomas, Andrew Peyton (2001). Clarence Thomas: A Biography, Encounter Books, ISBN 1-893554-36-8

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590 pp. ISBN 0815311761; ISBN 978-0815311768.

- Woodward, Robert (1979). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 9780380521838; ISBN 0380521830. ISBN 9780671241100; ISBN 0671241109; ISBN 0743274024; ISBN 9780743274029..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- About.com Quinn, Justin, A Profile of Clarence Thomas U.S. Conservative Politics.

- Clarence Thomas at the 2007 Annual National Lawyers Convention - November 2007.

- Cornell Law School Biography of Clarence Thomas.

- Michael Ariens, Clarence Thomas.

- Outline of the Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas Controversy

- Overview of Personal Memoir

- Oyez, Official Supreme Court media, Clarence Thomas biography.

- Supreme Court official biography (PDF format

- How to Read the Constitution Excerpt from Thomas's Walter B. Wriston Lecture to the Manhattan Institute in October 2008

- Transcripts of Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court

- Washington Post article about Thomas

- Coverage of Clarence Thomas from the New York Times

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2005-2006 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2006–2009 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2009-present Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- 1948 births

- African American judges

- African American memoirists

- Chairs of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

- College of the Holy Cross alumni

- Roman Catholics

- African American Catholics

- American Roman Catholics

- Roman Catholic jurists

- Conservatism in the United States

- Federalist Society members

- Georgia (U.S. state) lawyers

- Gullah

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- Living people

- People from McLean, Virginia

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by George H. W. Bush

- United States federal judges appointed by George H. W. Bush

- United States Supreme Court justices

- Yale Law School alumni