First Balkan War: Difference between revisions

Kushtrim123 (talk | contribs) rv edit-warring |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

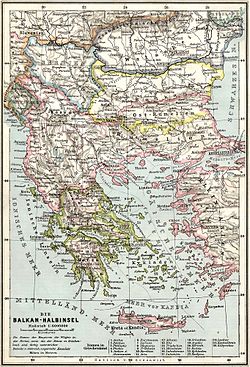

[[Image:Balkans-ethnique.JPG|right|thumb|250px|left|Ethnic composition of the Balkans according to the |

[[Image:Balkans-ethnique.JPG|right|thumb|250px|left|Ethnic composition of the Balkans according to the Atlas Général Vidal-Lablache, Librairie Armand Colin, Paris, 1898.]] |

||

[[Image:Edward Stanford 1877.jpg|right|thumb|250px|left|Ethnic composition map of the Balkans by the pro-Greek English cartographer [[Edward Stanford]], 1877.]] |

[[Image:Edward Stanford 1877.jpg|right|thumb|250px|left|Ethnic composition map of the Balkans by the pro-Greek English cartographer [[Edward Stanford]], 1877.]] |

||

Tensions among the [[Balkan]] states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]]-controlled [[Roumelia]], namely [[Eastern Roumelia]], [[Thrace]] and [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonia]], subsided somewhat following intervention by the [[Great Powers]] in the mid-19th century, aimed at securing both more complete protection for the provinces' [[Christian]] majority and protection of the [[status quo]]. By 1867, [[Serbia]] and [[Montenegro]] had all secured their independence, which was confirmed by the [[Treaty of Berlin (1878)|Treaty of Berlin]] a decade later. But the question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the [[Young Turk Revolution]] of July 1908 compelled the [[Sultan]] to restore the suspended Ottoman [[constitution]], and the significant developments in the years 1909-1911. |

Tensions among the [[Balkan]] states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]]-controlled [[Roumelia]], namely [[Eastern Roumelia]], [[Thrace]] and [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonia]], subsided somewhat following intervention by the [[Great Powers]] in the mid-19th century, aimed at securing both more complete protection for the provinces' [[Christian]] majority and protection of the [[status quo]]. By 1867, [[Serbia]] and [[Montenegro]] had all secured their independence, which was confirmed by the [[Treaty of Berlin (1878)|Treaty of Berlin]] a decade later. But the question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the [[Young Turk Revolution]] of July 1908 compelled the [[Sultan]] to restore the suspended Ottoman [[constitution]], and the significant developments in the years 1909-1911. |

||

Serbia's aspirations towards [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] were thwarted by the [[Austria-Hungary|Austrian]] annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then focused their attention to the south for expansion. After the annexation the [[Young Turks]] tried to induce the Muslim population of [[Bosnia]] to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. These immigrants were settled by the Ottoman authorities in those districts of north Macedonia where the Muslim population was weak. The experiment proved disastrous. Those elements of the population which could be induced to emigrate were largely considered to be ignorant, unruly, fanatical, and economically worthless. Their presence in Kosovo and north Macedonia proved to be a catastrophe for the Empire since they readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims in the series of Albanian uprisings before and during the spring of 1912. These Muslim revolutionaries were joined by some of the Ottoman troops, who had been operating against them, mostly of Albanian origin. In May 1912 the Albanian revolutionaries after driving out the Ottomans from [[Skopje]] continued towards [[Bitola]] forcing the [[Ottomans]] to recognize extented regions in western Balkans as Albanian, in June 1912. For Serbia this was also considered problematic. After its hopes of northern expansion were closed due to Austria's annexation of Bosnia it now found the last direction of possible expansion also closing due to the creation of Albania as a state. For Serbia it meant a struggle against time to avoid the creation of the Albanian state. |

Serbia's aspirations towards [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] were thwarted by the [[Austria-Hungary|Austrian]] annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then focused their attention to the south for expansion. After the annexation the [[Young Turks]] tried to induce the Muslim population of [[Bosnia]] to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. These immigrants were settled by the Ottoman authorities in those districts of north Macedonia where the Muslim population was weak. The experiment proved disastrous. Those elements of the population which could be induced to emigrate were largely considered to be ignorant, unruly, fanatical, and economically worthless. Their presence in Kosovo and north Macedonia proved to be a catastrophe for the Empire since they readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims in the series of Albanian uprisings before and during the spring of 1912. These Muslim revolutionaries were joined by some of the Ottoman troops, who had been operating against them, mostly of Albanian origin. In May 1912 the Albanian revolutionaries after driving out the Ottomans from [[Skopje]] continued towards [[Bitola]] forcing the [[Ottomans]] to recognize extented regions in western Balkans as Albanian, in June 1912. For Serbia this was also considered problematic. After its hopes of northern expansion were closed due to Austria's annexation of Bosnia it now found the last direction of possible expansion also closing due to the creation of Albania as a state. For Serbia it meant a struggle against time to avoid the creation of the Albanian state. |

||

Revision as of 23:07, 12 March 2010

| First Balkan War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkan Wars | |||||||

The territorial gains of the Balkan states after the 1st Balkan war and the line of expansion according to the prewar secret agreement between Serbia and Bulgaria. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Balkan League: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 336,742 men initially[1] |

Bulgaria 350,000+[2], Serbia 230,000 men[3], Greece 125,000 men[4], Montenegro 44,500 men[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

[6] |

[6] | ||||||

The First Balkan War, which lasted from October 1912 to May 1913, pitted the Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria) against the Ottoman Empire. The combined armies of the Balkan states overcame the numerically inferior and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies, and achieved rapid success. As a result of the war, almost all remaining European territories of the Ottoman Empire were captured and partitioned among the allies. Ensuing events also led to the creation of an independent Albanian state. Despite its success, Bulgaria was dissatisfied with the peace settlement and with the Ottoman threat gone, soon started a Second Balkan War against its former allies.

Background

Tensions among the Balkan states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of Ottoman-controlled Roumelia, namely Eastern Roumelia, Thrace and Macedonia, subsided somewhat following intervention by the Great Powers in the mid-19th century, aimed at securing both more complete protection for the provinces' Christian majority and protection of the status quo. By 1867, Serbia and Montenegro had all secured their independence, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin a decade later. But the question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the Young Turk Revolution of July 1908 compelled the Sultan to restore the suspended Ottoman constitution, and the significant developments in the years 1909-1911.

Serbia's aspirations towards Bosnia and Herzegovina were thwarted by the Austrian annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then focused their attention to the south for expansion. After the annexation the Young Turks tried to induce the Muslim population of Bosnia to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. These immigrants were settled by the Ottoman authorities in those districts of north Macedonia where the Muslim population was weak. The experiment proved disastrous. Those elements of the population which could be induced to emigrate were largely considered to be ignorant, unruly, fanatical, and economically worthless. Their presence in Kosovo and north Macedonia proved to be a catastrophe for the Empire since they readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims in the series of Albanian uprisings before and during the spring of 1912. These Muslim revolutionaries were joined by some of the Ottoman troops, who had been operating against them, mostly of Albanian origin. In May 1912 the Albanian revolutionaries after driving out the Ottomans from Skopje continued towards Bitola forcing the Ottomans to recognize extented regions in western Balkans as Albanian, in June 1912. For Serbia this was also considered problematic. After its hopes of northern expansion were closed due to Austria's annexation of Bosnia it now found the last direction of possible expansion also closing due to the creation of Albania as a state. For Serbia it meant a struggle against time to avoid the creation of the Albanian state.

The timetable of the creation of the Balkan League indicates that the increasing prewar understanding between Serbia and Bulgaria went on parallel to the success of the Albanian Uprising, making the uprising the triggering issue behind the Serbo-Bulgarian agreement and therefore the Balkan Wars. On the other hand, Bulgaria used the favorable timing in forcing Serbia to come to painful compromises regarding its aspirations toward Vardar Macedonia, since the party under time-pressure was Serbia[8]. The agreement provided that in the event of a victorious war against the Ottomans, Bulgaria would receive all of Macedonia south of the Kriva Palanka-Ohrid line. Serbia's expansion was to be to the north of this line, including Kosovo, and out to the coast of the Adriatic sea to the west. This includes the northern half of modern Albania, giving Serbia access to the sea. If Serbia intended to honour the treaty, then it had sold Macedonia to buy Albania.

Bulgaria had held a long-term policy regarding the Ottomans since restoring its independence during the Russo-Turkish War. After the successful coup d'état for the unification with Eastern Rumelia[9], it had orchestrated a methodical scenario of indirect expansion through the creation, in the multi-ethnic Ottoman-held Macedonia, of a revolutionary organization, the IMRO, allegedly without national colour. IMRO's rhetoric claimed to be speaking generally for liberation on behalf of the “Macedonian People”, declaring its anti-chauvinism. In fact it was a Bulgarian backed organization created with a secret agenda to facilitate the incorporation of Thrace (Eastern and Western) and Macedonia (Aegean and Vardar) into a new autonomous state, as an intermediate step before the unification with Bulgaria could take place in the same way as with Eastern Rumelia. After an initial success Serbia and especially Greece realized the true purpose of IMRO and consequently a vicious guerilla war (see Macedonian Struggle) broke out between Bulgarian and Greek backed groups within Macedonia, ending when the Young Turks movement came into power in the Ottoman Empire with its initially democratic and modernization agenda. Bulgaria then turned to the more orthodox method of expansion through winning a war, building a large army for that purpose and started to see itself as the "Prussia of the Balkans"[10]. But even so, it was clear that Bulgaria could not win a war against the Ottomans alone.

In Greece, Army officers had revolted in August 1909 and secured the appointment of a progressive government under Eleftherios Venizelos, which they hoped would resolve the Cretan issue in Greece's favour and reverse their defeat of 1897 at the hands of the Ottomans. An emergency military reorganization had begun for that purpose led by a French military mission, but its work interrupted at the outbreak of war. In the discussions that led Greece to join the League Bulgaria refused to commit to any agreement on the distribution of territorial gains, unlike the deal with Serbia over Macedonia. Bulgaria's diplomatic policy was to push Serbia into an agreement limiting its access to Macedonia[11], while at the same time refusing any such agreement with Greece, believing that its army would be able to occupy the larger part of Aegean Macedonia and the important port city of Thessaloniki before the Greeks.

In 1911, Italy had launched an invasion of Tripolitania, which was quickly followed by the occupation of the Dodecanese Islands. The Italians' decisive military victories over the Ottoman Empire greatly influenced the Balkan states towards the possibility of winning a war against the Ottomans. Thus in the spring and summer of 1912 these consultations between the various Christian Balkan nations had resulted in a network of military alliances which became known as the Balkan League.

The Great Powers, most notably France and Austria-Hungary, reacted to this diplomatic grouping by trying to dissuade the League from going to war, but failed. In late September, both the League and the Ottoman Empire mobilized their armies. Montenegro was the first to declare war, on September 25 (O.S.)/October 8. The other three states, after issuing an impossible ultimatum to the Porte on October 13, declared war on the Empire on October 17.

Order of battle and plans

The Ottoman order of battle when the war broke out constituted from a total of 12,024 officers 324,718 men, 47,960 animals, 2,318 artillery pieces and 388 machine guns. From these a total 920 officers and 42,607 men had been assigned in non-divisional units and services, the remained 293,206 officers and men being assigned into four Armies [12]. Opposing them and in continuation of their secret prewar settlements of expansion between them, the three Slavic allies (Bulgarian, Serbs and Montenegrins) had led out extensive plans to coordinate their war efforts: the Serbs and Montenegrins in the theater of Sandžak, the Bulgarians and Serbs in the Macedonian and Thracian theaters. The bulk of the Bulgarian forces (346,182 men) was targeting Thrace, pitted against the Thracian Ottoman Army of 96,273 men and about 26,000 garrison troops.[13] or about 115,000 in total, according to both Hall's, Erickson's and the Turkish Gen. Staff's study of 1993, books. The remaining Ottoman army of about 200,000[14] was located in Macedonia, pitted against the Serbian (234,000 Serbs and 48,000 Bulgarians under the Serbians orders) and Greek (115,000 men) armies, and divided into the Vardar and Macedonian Ottoman armies with independent static guards around the fortress cities of Ioannina (against the Greeks in Epirus) and Shkodër (against the Montenegrins in north Albania).

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was militarily the most powerful of the four states, with a large, well-trained and well-equipped army.[15] Bulgaria mobilized a total of 599,878 men out of a population of 4,300,000.[16] The Bulgarian field army counted for 9 infantry divisions, 1 cavalry division and 1116 artillery units.[15] Commander-in-Chief was Tsar Ferdinand, while the actual command was in the hands of his deputy, General Michail Savov. The Bulgarians also possessed a small navy of six torpedo boats, which were restricted to operations along the country's Black Sea coast.[17]

Bulgaria's war aims were focused on Thrace and Macedonia. It deployed its main force in Thrace, forming three armies. The First Army (79,370 men), under general Vasil Kutinchev with 3 infantry divisions, was deployed to the south of Yambol, with direction of operations along the Tundzha river. The Second Army (122,748 men), under general Nikola Ivanov, with 2 infantry divisions and 1 infantry brigade, was deployed west of the First and was assigned to capture the strong fortress of Edirne. According to the plans, the Third Army (94,884 men), under general Radko Dimitriev, was deployed east of and behind the First, and was covered by the cavalry division hiding it from the Turkish view. The Third Army had 3 infantry divisions and was assigned to cross the Stranja mountain and to take the fortress of Kirk Kilisse. The 2nd (49,180) and 7th (48,523 men) divisions were assigned independent roles, operating in Western Thrace and eastern Macedonia respectively.

Serbia

Serbia called upon about 230,000 men (out of a population of 2,912,000 people) with about 228 guns, grouped in 10 infantry divisions, two independent brigades and a cavalry division, under the effective command of former War Minister Radomir Putnik.[16] The Serbian High Command, in its pre-war wargames, had concluded that the likeliest site of the decisive battle against the Turkish Vardar Army would be on the Ovče Polje plateau, before Skopje. Hence, the main forces were formed in three armies for the advance towards Skopje, while a division and an independent brigade were to cooperate with the Montenegrins in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar.

The First Army (132,000 men) was commanded by General Petar Bojović, and was the strongest in number and force, forming the center of the drive towards Skopje. The Second Army (74,000 men) was commanded by General Stepa Stepanović, and consisted of one Serbian and one Bulgarian (7th Rila) division. It formed the left wing of the Army and advanced towards Stracin. The inclusion of a Bulgarian division was according to a pre-war arrangement between Serbian and Bulgarian armies, but that division ceased to obey orders of Gen. Stepanović as soon as the war began, followed only the orders of the Bulgarian High Command. The Third Army (76,000 men) was commanded by General Božidar Janković and, being the right-wing army, had the task to liberate Kosovo and then join the other armies in the expected battle at the Ovče Polje. There were also two other concentrations in northwestern Serbia across the Serbo-Austrohungarian borders, the Ibar Army (25,000 men) under General Mihail Zhivkovich and the Javor brigade (12,000 men) under Lt Colonel Milovoje Anđelković.

Greece

Greece (a state of 2,666,000 people) was considered the weakest of the three main allies, since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered an easy defeat against the Ottomans 16 years before in the Greco-Turkish War. However Greece had a strong navy, which was vital to the League, as was the only allied navy that could possibly prevent Turkish reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry in the League: "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between Salonica and Gallipoli."[17]

The army was still undergoing reorganization by a French military mission when the war began. Upon mobilization, it was grouped in two Armies. The Army of Thessaly, under Crown Prince Constantine, with Lt Gen Panagiotis Danglis as his chief of staff, but the real organizational and strategic mind behind the scene was major (later General) Ioannis Metaxas. It fielded 7 infantry divisions, a cavalry regiment and 4 independent Evzones battalions, equaling roughly 100,000 men. It was expected to overcome the fortified Turkish border positions and advance towards south and central Macedonia, aiming to take Thessaloniki and Bitola.

Further 10,000 to 13,000 men in eight battalions were assigned to the Army of Epirus under Lt Gen Konstantinos Sapountzakis, which was intended to advance into Epirus. As it had no hope of capturing its heavily fortified capital, Ioannina, its initial mission was simply to pin down the Turkish forces there until sufficient reinforcements could be sent from the Army of Thessaly after its successful conclusion of operations.

The Greeks had a relatively modern navy, strengthened by the purchase of numerous new units and undergoing reforms under the supervision of a British mission. The core unit of the fleet was the fast armoured cruiser Averof, built in 1910. There were also 8 modern destroyers built in 1912 and 8 more built in 1906. Although the Greeks' other main surface units were rather old, it was the possession of these well-crewed new ships that ensured naval supremacy in the Aegean Sea.[18] The bulk of the navy was assigned to the Fleet of the Aegean, placed under the command of Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis, a brilliant naval officer. Other small task forces of destroyers and torpedo boats were also assigned to scour the Aegean and Ionian seas of small Ottoman vessels.

Ottoman Empire

In 1912, the Ottomans found themselves in a difficult position. They had a large population of 26,000,000, but only 6,130,000 of them lived in the European part of the Empire, and of these only 2,300,000 were Muslims, the rest being Christians, considered unfit for conscription. The very poor transport network, especially in the Asian part, dictated that the only reliable way for a mass transfer of troops to the European theater was by sea, but that was under question due to the presence of the Greek fleet in the Aegean Sea. They were also still engaging in a protracted war with the Italians in Libya (and by now in the Dodecanese islands of the Aegean), which had dominated the Ottoman military effort for over a year and would last until 15 October, a few days after the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans. They were therefore unable to significantly reinforce their positions in the Balkans as the relations with the Balkan states deteriorated over the course of the year.[19]

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by domestic strife caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counter-revolutionary coup several months later (see Countercoup (1909) and 31 March Incident). An effort had been made to reorganize the army by a German mission, but its effects had not taken hold.[16] The regular army (Nizam) was composed of well-equipped and trained active divisions, but the reserve units (Redif) that reinforced it were ill-equipped, especially in artillery, and badly trained.

The Ottomans had three armies in Europe (the Macedonian, Vardar and Thracian Armies) with 1,203 pieces of mobile and 1,115 fixed artillery on fortified areas. Western Group of Armies in Macedonia fielded at least 200,000 men[14] detailed against the Greek and the Serbian-Montenegro Armies and the First Army in Thrace had at least 115,000 men detailed against the Bulgarian Army.[19]

The Thracian Army was deployed against the Bulgarians. It was commanded by Nazim Pasa and numbered seven corps of 11 Regular Infantry, 13 Redif and 1+ Cavalry divisions:

- I Corps with 3 divisions (2nd Infantry (minus regiment), 3rd Infantry and 1st Provisional divisions).

- II Corps with 3 divisions (4th (minus regiment) and 5th Infantry and Usak Redif divisions).

- III Corps with 4 divisions (7th, 8th and 9th Infantry Divisions, all minus a regiment, and the Afyonkarahisar Redif Division).

- IV Corps with 3 divisions (12th Infantry Division (minus regiment), Izmit and Bursa Redif divisions).

- XVII Corps with 3 divisions (Samsun, Ergli and Izmir Redif divisions).

- Edirne Fortified Area with 6+ divisions (10th and 11th Infantry, Edirne, Babaeski and Gumulcine Redif and the Fortress division, 4th Rifle and 12th Cavalry regiments).

- Kircaali Detachment with 2+ divisions (Kircaali Redif, Kircaali Mustahfiz division and 36th Infantry Regiment).

- An independent cavalry division and the 5th Light Cavalry Brigade

The Western Group of Armies (Macedonian and Vardar) was composed of ten corps with 32 infantry and two cavalry divisions.

Against the Serbs the Ottomans deployed the Vardar Army (HQ in Skopje under Halepli Zeki Pasa) with five Corps of 18 Infantry divisions, one cavalry division and two independent cavalry brigades under the:

- V Corps with 4 divisions (13th, 15th, 16th Infantry and the Istip Redif divisions)

- VI Corps with 4 divisions (17th, 18th Infantry and the Monastir and Drama Redif divisions)

- VII Corps with 3 division (19th Infantry and Skopje and Pristina Redif divisions)

- II Corps with 3 divisions (Usak, Denicli and Izmir Redif divisions)

- Sandžak Corps with 4 divisions (20th Infantry (minus regiment), 60th Infantry, Mitrovice Redif Division, Taslica Redif Regiment, Firzovik and Taslica Detachment)

- An independent Cavalry Division and the 7th and 8th Cavalry Brigades.

The Macedonian Army (HQ in Thessaloniki under Ali Riza Pasa) was composed of 14 divisions in five corps detailed against Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro.

Against Greece, 7+ divisions were deployed:

- VIII Corps with 3 divisions (22nd Infantry and Naslic and Aydin Redif divisions).

- Ioannina Corps with 3 divisions (23rd Infantry, Ioannina Redif and Bizani Fortress divisions).

- Thessaloniki Redif division and Karaburun Detachment as independent units.

Against Bulgaria in the South-Eastern Macedonia, 2 divisions forming the Ustruma Corps (14th Infantry and Serez Redif divisions, plus the Nevrekop Detachment) were deployed.

Against Montenegro, 4+ divisions were deployed:

- Shkodër Corps with 2+ divisions (24th Infantry, Elbasan Redif, Shkodër Fortified Area and Ipec Detachment)

- Independent Corps with 2 divisions (21st Infantry and Prizren Redif divisions)

According to the organizational plan the men of the Western Group had to number 598,000. But slow mobilization procedures and the poor railroad efficiency reduced drastically the available men, so that when war began, according to the Western Army Staff there were only 200,000 men available.[14] Although during the next period more men reached the units, due to the war casualties, the Western Group never came near its nominal strength. In time of war the Ottomans planned to bring more troops in from Syria, both Nizamiye and Redif.[14] Greek naval supremacy however prevented those reinforcements from arriving. Instead those soldiers had to deploy via the land route, and most never made it to the Balkans.

The Ottoman General Staff, assisted by the German Military Mission, developed 12 war plans, designed to counter various combinations of opponents. Work on plan #5, which was against a combination of Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro, was very advanced, and had been sent to the Army staffs for them to develop local plans.[20]

Operations

Montenegro started the First Balkan War by declaring war against the Ottomans on 8 October [O.S. 25 September] 1912.

The Bulgarian theater of operations

The western region of the Balkans, including Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia was less important to the resolution of the war and the survival of the Ottoman Empire than the Thracian theater, where the Bulgarians fought major battles against the Turks. But although the geography dictated that Thrace would be the major battlefield in a war with the Ottoman Empire[21], the position of the Ottoman Army there was jeopardized by erroneous intelligence estimates of their opponents' order of battle. Unaware of the secret prewar political and military settlement over Macedonia between Bulgaria and Serbia, the Ottoman leadership assigned the bulk of their forces there. The German ambassador Hans Baron von Wangenheim, one of the most influential people in the Ottoman capital, had reported to Berlin on October 21 that the Turks believed that the bulk of the Bulgarian army would deployed in Macedonia with the Serbs. Subsequently the Ottoman HQ under Abdullah Pasha expected to meet only three Bulgarian infantry divisions, accompanied by cavalry, east of Edirne.[22] According to E. J. Erickson this assumption possibly resulted from their analysis of the objectives of the Balkan Pact - but it had deadly consequences for the Ottoman Army in Thrace, which would have to defend the area against the bulk of the Bulgarian army against impossible odds.[23] This misappraisal was also the reason of the catastrophic aggressive Ottoman strategy at the start of the campaign in Thrace.

Bulgarian offensive and advance to Çatalca

In the Thracian front the Bulgarian army had placed 346,182 men against the Ottoman 1st Army with 105,000 men in eastern Thrace and the Kircaali detachment of 24,000 men in western Thrace. The Bulgarian forces were divided into the 1st (Lt. Gen. Vasil Kutinchev), 2nd (Lt. Gen. Nikola Ivanov) and 3rd (Lt. Gen. Radko Dimitriev) Bulgarian Armies of 297,002 men in the eastern part and 49,180 (33,180 regulars and 16,000 irregulars) under the 2nd Bulgarian Division (Gen. Stilian Kovachev) in the western part.[24] The first large-scale battle occurred against the Edirne-Kirk Kilisse defensive line, where the Bulgarian 1st and 3rd Armies (together 174,254 men) defeated the Ottoman East Army (of 96,273 combatants),[24][25] near Gechkenli, Seliolu and Petra. The Ottoman XV Corps urgently left the area to defend the Gallipoli peninsula against an expected Greek amphibious assault, which in the event never materialized[26]. The absence of this Corps created an immediate vacuum between Edirne and Demotika, and the Eastern Army's IV Corps was moved there to replace it. Thus two complete army corps were removed from the Eastern Army's order of battle, effectively splitting the Ottoman Thracian front in two[26]. As a consequence the Kirk Kilisse was taken without resistance under the pressure of the Bulgarian Third Army,[26] and the fortress of Edirne, with some 61,250 men, was isolated and besieged although for the time being no assault was possible due to the lack of siege equipment in the Bulgarian inventory[27]. Another consequence of the Greek naval supremacy in Aegean was that the Ottoman forces did not receive the reinforcements projected in the war plans, consisting of a further corps to be transferred by sea from Syria and Palestine.[28] Thus the Greek Navy played a crucial albeit indirect role in the Thracian campaign, by neutralizing three corps, a significant portion of the Ottoman Army, in the all-important opening round of the war.[28] Another, more direct role, was the emergency transportation of the of the Bulgarian 7th Rila Division from the Macedonian to the Thracian front after the termination of the operations there[29].

After the battle of Kirk Kilisse the Bulgarian high command decided to wait a few days, a decision which allowed the Turks to occupy a new defensive position on the Luleburgaz-Karaagach-Bunarhisar line. Despite this, the Bulgarian attack by First and Third Army which together accounted for 107,386 rifleman,3115 cavalry,116 machine guns and 360 artillery pieces defeated the reinforced Turkish Army consisting of 126,000 riflemen,3500 cavalry,96 machine guns and 342 artillery pieces[30] and reached the Sea of Marmara. In terms of forces engaged it was the largest battle fought in Europe between the end of the Franco-Prussian War and the beginning of the First World War[30].As a result of it the Turks were pushed to their final defensive position across the Çatalca Line protecting the peninsula on which Constantinople is located. There they succeeded in stabilizing the front with the help of fresh reinforcements from the Asian provinces. The line had been constructed during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8 under the directions of a German engineer in Ottoman service, von Bluhm Pasha, but was considered obsolete by 1912.[31].

Meanwhile the forces of the Bulgarian 2nd Thracian division, 49,180 men divided into the Haskovo and Rhodope detachments, advanced toward the Aegean Sea. The Ottoman Kircaali detachment (Kircaali Redif and Kircaali Mustahfiz Divisions and 36th Regiment with 24,000 men), tasked with defending a 400 km front across the Thessaloniki-Dedeagach railroad, failed to offer serious resistance and on 26 November their commander Yaver Pasha was captured together with 10,131 officers and men by Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps. After the occupation of Thessaloniki by the Greek army, his surrender completed the isolation of the Ottoman forces in Macedonia from those in Thrace.

On 17 November [O.S. 4 November] 1912, the offensive against the Çatalca Line began, despite clear warnings from Russia that if the Bulgarians occupied Constantinople it would attack them. This was an early evidence of the lack of realistic thinking of the Bulgarian leadership[32]. The Bulgarians launched their attack along the defensive line with 176,351 men and 462 artillery pieces against the Ottomans' 140,571 men and 316 artillery pieces,[33] but despite Bulgarian superiority, the Ottomans succeeded to repulse them. An armistice was consequently agreed on 3 December [O.S. 20 November] 1912 between the Ottomans and Bulgaria, the latter also representing Serbia and Montenegro, and peace negotiations began in London. Greece also participated in the conference, but refused to agree to a truce, continuing its operations in the Epirus sector. The negotiations were interrupted on 5 February [O.S. 23 January] 1913, when a Young Turk coup d'état in Constantinople under Enver Pasha overthrew the government of Kiamil Pasha. Upon expiration of the armistice, on February 16, hostilities recommenced.

The Ottoman counteroffensive, the fall of Edirne, and Serbo-Bulgarian friction

On 20 February Ottoman forces began their attack, both in Çatalca and south, at Gallipoli. There the Ottoman X Corps, with 19,858 men and 48 guns, landed at Şarköy, at the same time as an attack of around 15,000 men supported by 36 guns (part of the 30,000-strong Ottoman army isolated in the Gallipoli peninsula) at Bulair further south. Both attacks were supported by fire from Ottoman warships, and were intended in the long term to relieve pressure on Edirne. Confronting them were about 10,000 men with 78 guns.[34] The Ottomans were probably unaware of the presence in the area of the newly-formed 4th Bulgarian Army of 92,289 men under General Stiliyan Kovachev. The Ottoman attack in the thin isthmus, with a front of just 1,800m, was hampered by thick fog and strong Bulgarian artillery and machine gun fire. As a result the attack stalled, and was repulsed by a Bulgarian counterattack. By the end of the day both armies had returned to their original positions. Meanwhile the Ottoman X Corps, which had landed at Şarköy, advanced until by 23 February [O.S. 10 February] 1913 the reinforcements sent by General Kovachev succeeded in halting them. Casualties on both sides were light. After the failure of the frontal attack in Bulair, the Ottoman forces at Şarköy re-embarked into their ships on 11 February and were transported to Gallipoli.

The Ottoman attack at Çatalca, directed against the powerful Bulgarian First and Third Armies, was initially launched only as a diversion from the Gallipoli-Şarköy operation, pinning down the Bulgarian forces in situ. Nevertheless, it resulted in unexpected success. In the north the Bulgarians were forced to withdraw about 15 km and to the south over 20 km to their secondary defensive positions. With the end of the attack in Gallipoli the Ottomans cancelled the operation, reluctant to leave the Çatalca Line, but several days passed before the Bulgarians realized that the offensive was over. By February 15 the front had again stabilized but the fighting along the static lines continued until the armistice. The battle, which resulted in heavy Bulgarian casualties, could be characterized as an Ottoman victory at the tactical level, but strategically it was a failure, since it did nothing to prevent the failure of the Gallipoli-Şarköy operation or relieve the pressure on Edirne.

The failure of the Şarköy-Bulair operation and the deployment of the 2nd Serbian Army together with its much needed heavy siege artillery sealed Edirne's fate. On 11 March after a two weeks bombardment that destroyed much of the fortified structures around the city, the final assault started with Allied forces enjoying a crushing superiority over the Ottoman garrison. Under the command of General Nikola Ivanov, the Bulgarian 2nd Army with 106,425 men and two Serb divisions with 47,275 men eventually conquered the city, but at a high price: the Bulgarians suffering 8,093 and the Serbs 1,462 casualties.[35] The Ottoman casualties for the entire Adrianople campaign reached 13,000 killed. The number of prisoners is less clear. The Turks began the war with 61,250 men in the Adrianople fortress[36]. Richard Hall notes that 60,000 men were captured. Adding to the 13,000 killed, the modern Turkish General Staff History notes that 28,500 man survived captivity[37] leaving only 20,000 men unaccounted[38] as possibly captured (including the unspecified number of wounded). Bulgarian losses for the entire Adrianople campaign amounted to 18,282. According to both R.C. Hall and E.J. Erickson, the assault was an unnecessary bloodshed, it was more of a political decision and took place only to inflate the national pride of Tsar Ferdinand and some Bulgarian politicians, since the fortress would have to surrender anyhow by the end of the month due to starvation. The most important result however was that now the Ottoman command lost all hopes of regaining the initiative, which made any further fighting pointless[39].

The battle had major and key results in the Serbo-Bulgarian relations putting the seeds of the countries' confrontation some months later. The Bulgarian censor rigorously cut any references about the Serbian participation in the operation in the telegrams of the foreign correspondents and thus the public opinion in Sofia failed to realise the crucial services Serbia rendered in the battle. Accordingly the Serbs claimed that their troops of the 20th regiment there, were those who captured the Turk commander of the city and their Colonel Gavrilović was the allied officer who accepted Shukri's official surrender of the Ottoman guard of the fortress, a statement that Bulgarians disputed. Subsequently the Serbs officially protested pointing out among others that although they sent their troops in Edirne to win for Bulgaria territory the acquisition of which had never been foresee by their mutual treaty[40], the Bulgarians never fulfilled that clause of the treaty requiring Bulgaria to send 100,000 men to help Serbians in their Vardar front. In which the Bulgarians answered that their Staff had informed the Serbian about that in 23rd of August. The friction elevated some weeks later when the Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support of their Adriatic claims. In which the Serbs angrily answered that that was a clear withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion. The Bulgarians answered that to them the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement was active and thus the Serbs must surrender the area to them as agreed. [41] In which the Serbs answered by accusing the Bulgarians for maximalism pointing out that if they lose both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia their participation in the common war would had been virtually for nothing. The tension soon expressed to a series of hostile incidents between the two armies in their common line of occupation across the Vardar valley. The developments essentially ended the Serbo-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable.

The Greek theater of operations

Macedonian front

Ottoman intelligence had also disastrously misread Greek military intentions. In retrospect, it would appear that the Ottoman staffs believed that the Greek attack would be shared equally between the two major avenues of approach, Macedonia and Epirus. The 2nd Army staff had therefore evenly balanced the combat strength of the seven Ottoman divisions between the Yanya Corps and VIII Corps, in Epirus and southern Macedonia respectively. This was a fatal decision for the Western Group of Armies, since it led to the early loss of the strategic center of all three Macedonian fronts, the city of Thessaloniki, a fact that sealed their fate. The Greek Army also fielded seven divisions, but, having the initiative, concentrated all seven against VIII Corps, leaving only a number of independent battalions of scarcely divisional strength in the Epirus front.[42]. In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, the Army of Thessaly seized the city. The loss of this city was a strategic disaster for the Turks. In the absence of secure sea lines of communications, the retention of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople corridor was essential to the overall strategic posture of the Ottoman Empire. Once this was gone, the defeat of the Ottoman Army became inevitable. To be sure, the Bulgarians and the Serbs played an important role in the defeat of the main Ottoman armies. Their great victories at Kirkkilise, Luleburgaz, Kumanova, and Monastir shattered the Eastern and Vardar Armies. However, these victories were not decisive in the sense that they ended the war. The Ottoman field armies survived, and in Thrace, they actually grew stronger day by day. In the strategic point of view these victories were enabled partially by the weakened condition of the Ottoman armies brought about by the active presence of the Greek army and fleet[43].

With the declaration of war, the Greek Army of Thessaly under Crown Prince Constantine advanced to the north, successfully overcoming Ottoman opposition in the fortified Straits of Sarantaporo. After another victory at Giannitsa on 2 November [O.S. 20 October] 1912, Thessaloniki and its garrison of 26,000 men surrendered to the Greeks on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1912. Two Corps HQs (Ustruma and VIII), two Nizamiye divisions (14th and 22nd) and four Redif divisions (Salonika, Drama, Naslic and Serez) were thus lost to the Ottoman order of battle. Additionally, the Turks lost 70 artillery pieces, 30 machine guns and 70,000 rifles (Thessaloniki was the central arms depot for the Western Armies). The Turks estimated that 15,000 officers and men had been killed during the campaign in south Macedonia, bringing total losses up to 41,000 soldiers.[14] Another direct consequence was that the destruction of the Macedonian Army sealed the fate of the Ottoman Vardar Army, which was fighting the Serbs to the north. The fall of Thessaloniki left it strategically isolated, without logistical supply and depth to maneuver, ensuring its destruction.

Upon learning of the outcome of the battle of Gianitsa, the Bulgarian high command urgently dispatched their 7th Rila Division from the north in the direction of the city. The division arrived there a week later, the day after its surrender to the Greeks. Until November 10, the Greek-occupied zone had been expanded to the line from Lake Dojran to the Pangaion hills west to Kavalla. In western Macedonia however, the lack of coordination between the Greek and Serbian HQs cost the Greeks a setback in the Battle of Vevi on 15 November [O.S. 2 November] 1912, when the Greek 5th Division crossed its way with the VI Ottoman Corps (a part of the Vardar Army consisting of the 16th, 17th and 18th Nizamiye divisions), retreating to Albania following the battle of Prilep against the Serbs. The Greek division, surprised by the presence of the Ottoman Corps, isolated from the rest of Greek army and outnumbered by the now counterattacking Ottomans centered on Bitola, was forced to retreat. As a result, the Serbs beat the Greeks to Bitola.

Epirus front

In the Epirus front the Greek army was initially heavily outnumbered, but due to the passive attitude of the Ottomans succeeded in conquering Preveza (21 October 1912) and pushing north to the direction of Ioannina. On November 5, a small force from Corfu made a landing and captured the coastal area of Himarë without facing significant resistance,[44] and on November 20 Greek troops from western Macedonia entered Korce. However, Greek forces in the Epirote front had not the numbers to initiate an offensive against the German-designed defensive positions of Bizani that protected the city of Ioannina, and therefore had to wait for reinforcements from the Macedonian front.[45]

After the campaign in Macedonia was over, a large part of the Army was redeployed to Epirus, where Crown Prince Constantine himself assumed command. In the Battle of Bizani the Ottoman positions were breached and Ioannina taken on 6 March [O.S. 22 February] 1913. During the siege, on 8 February 1913, the Russian pilot N. de Sackoff, flying for the Greeks, became the first pilot ever shot down in combat, when his biplane was hit by ground fire following a bomb run on the walls of Fort Bizani. He came down near small town of Preveza, on the coast north of the Aegean island of Lefkas, secured local Greek assistance, repaired his plane and resumed flight back to base.[46] The fall of Ioannina allowed the Greek army to continue its advance into northern Epirus, the southern part of modern Albania, which it occupied. There its advance stopped, although the Serbian line of control was very close to the north.

At sea, the Greek fleet took action from the first day of the war. From 6 October until 20 December 1912, Greek naval and army detachments seized almost all islands of the Eastern and North Aegean sea, and established a forward base at Moudros Bay in Lemnos, controlling the exits of the Dardanelles. Lieutenant Nikolaos Votsis scored a major success for Greek morale on 8 November, when he sailed his torpedo boat under the cover of night into the harbor of Thessaloniki and sank the old Ottoman ironclad battleship Feth-i-Bulend. Other Greek torpedo boats attacked minor Ottoman war vessels throughout the Aegean and Ionian seas.

The main Ottoman fleet remained inside the Dardanelles for the early part of the war; but when the land war took a critical turn against the Ottoman army, necessitating the urgent reinforcement of the European theater, the Ottoman fleet tried to enter the Aegean. Its sortie on 16 December [O.S. 3 December] 1912 was defeated in the Naval Battle of Elli, largely through the tactical initiative of Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis and the superior speed of the Greek flagship, Georgios Averof. In preparation for the next attempt to break the Greek blockade, the Ottoman Admiralty then decided to create a diversion by sending the light cruiser Hamidiye, captained by Rauf Orbay, to raid Greek merchant shipping in Aegean. It was hoped that the Averof, the only major Greek unit fast enough to catch Hamidiye, would be drawn in pursuit and leave the remainder of the Greek fleet weakened. In the event, Hamidiye slipped through the Greek patrols and bombarded the harbor of the Greek island of Syros, damaging an anchored merchant ship before leaving the Aegean for the Eastern Mediterranean to finally take refuge in the Red Sea. Orders were indeed sent to Kountouriotis ordering him to hunt Hamidiye down; having guessed the Ottoman plan however, he refused, and four days later, on 18 January [O.S. 5 January] 1913, when the Ottoman fleet again sallied from the Straits, it was defeated for a second time in the Naval Battle of Lemnos. It was the last attempt of the Ottoman navy to leave the Dardanelles, thereby leaving the Greek navy dominant in the Aegean. General Ivanov, commander of the 2nd Bulgarian Army, acknowledged the role of the Greek fleet in the overall Balkan League victory by stating that "the activity of the entire Greek fleet was the chief factor in the general success of the allies".[47]

The Serb-Montenegrin theater of operations

The Serbian Army under General (later Marshal) Putnik dealt three decisive victories in Vardar Macedonia, its primary objective in the war, effectively destroying the Ottoman forces in the region and conquering north Macedonia. They also helped the Montenegrins to take the Sandžak and sent two divisions to help the Bulgarians at the siege of Edirne.

The last battle for Macedonia was the battle of Monastir, in which the remains of the Ottoman Vardar Army were forced to retreat to central Albania. After the battle, Prime Minister Pasic asked Gen. Putnik to take part in the race for Thessaloniki. Putnik declined and instead turned his army to the west, towards Albania, foreseeing that a future confrontation between the Greeks and Bulgarians over Thessaloniki could greatly help Serbia's own plans over Vardar Macedonia.

After the Great Powers applied pressure on them, the Serbs started to withdraw from northern Albania and the Sandžak, although they left behind their heavy artillery park to help the Montenegrins in the continuing siege of Shkodër. On 23 April 1913 the fortress' garrison was forced to surrender due to starvation.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Conclusion of the war and aftermath

The Treaty of London ended the First Balkan War on 30 May 1913. All Ottoman territory west of the Enez-Kıyıköy line was ceded to the Balkan League, according to the status quo at the time of the armistice. The treaty also declared Albania to be an independent state. Almost all of the territory that was designated to form the new Albanian state was currently occupied by either Greece or Serbia, which only reluctantly withdrew their troops. Having unresolved disputes with Serbia over the division of northern Macedonia and with Greece over southern Macedonia, Bulgaria was determined to solve the problems by force, so refused to demobilize its army. Seeing the omens Greece and Serbia settled their mutual differences and signed a military alliance on May 1, 1913, followed by a treaty of "mutual friendship and protection" on May 19/June 1, 1913. By this, the scene for the Second Balkan War was set.

Reactions among the Great Powers

The developments that led to the war did not go unnoticed by the Great Powers, but although there was an official consensus between the European Powers over the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which led to a stern warning to the Balkan states, unofficially each of them took a different diplomatic approach due to their conflicting interests in the area. As a result, any possible preventative effect of the common official warning was cancelled by the mixed unofficial signals, and failed to prevent or to stop the war:

- Russia was a prime mover in the establishment of the Balkan League and saw it as an essential tool in case of a future war against her rival, the Austro-Hungarian Empire[48]. But she was unaware of the Bulgarian plans over Thrace and Constantinople, territories on which she had long-held ambitions, and on which she had just secured a secret agreement of expansion from her allies France and Britain, as a reward in participating in the upcoming Great War against the Central Powers[1](for more, see Constantinople Agreement).

- France, not feeling ready for a war against Germany in 1912, took a totally negative position against the war, firmly informing her ally Russia that she would not take part in a potential conflict between Russia and Austro-Hungary if it resulted from the actions of the Balkan League. The French however failed to achieve British participation in a common intervention to stop the Balkan conflict.

- The British Empire, although officially a staunch supporter of the Ottoman Empire's integrity, took secret diplomatic steps encouraging the Greek entry into the League in order to counteract Russian influence. At the same time she encouraged the Bulgarian aspirations over Thrace, preferring a Bulgarian Thrace to a Russian one, despite the assurances she had given to the Russians in regard of their expansion there.

- Austria-Hungary, struggling for an exit from the Adriatic and seeking ways for expansion in the south at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, was totally opposed to any other nation's expansion in the area. At the same time, the Habsburg empire had its own internal problems with the significant Slav populations that campaigned against the German-Hungarian control of the multinational state. Serbia, whose aspirations in the direction of the Austrian-held Bosnia were no secret, was considered an enemy and the main tool of Russian machinations that were behind the agitation of Austria's Slav subjects. But failed to achieve German backup for firm reaction. Initially, Emperor Wilhelm II told the Archduke Franz Ferdinand that Germany was ready to support Austria in all circumstances - even at the risk of a world war, but Austro-Hungarians hesitated. Finally, in the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 the consensus was that Germany would not be ready for war until at least mid-1914 and notes about that passed to the Habsburgs. Consequently no actions could be taken when the Serbs acceded to the Austria ultimatum of October 18 and withdrawn from Albania.

- Germany, already heavily involved in the internal Ottoman politics, officially opposed a war against the Empire. But in her effort to win Bulgaria for the Central Powers, and seeing the inevitability of Ottoman disintegration, was playing with the idea to replace the Balkan positions of the Ottomans with a friendly Greater Bulgaria in her San Stefano borders. An idea that was based on the German origin of the Bulgarian King and his anti-Russian sentiments.

Finally, when Serb-Austrian tensions again grew hot in July 1914 when a Serbian backed organization assassinated the heir of the Austro-Hungarian throne, no one had strong reservations about the possible conflict and the First World War broke out.

| Battles of the First Balkan War | ||||||||

| Name | Attacking | Commander | Defending | Commander | Date | Winner | ||

| Battle of Kardzhali | Bulgarians | Col. Vasil Delov | Ottomans | Mehmed Yaver Pasha | Oct 21 1912 | Bulgarians | ||

| Battle of Sarantaporo | Greeks | Crown Prince Constantine | Ottomans | Oct 22 1912 | Greeks | |||

| Battle of Giannitsa | Greeks | Crown Prince Constantine | Ottomans | Hasan Tahsin Pasha | Nov 1 1912 | Greeks | ||

| Battle of Kumanovo | Serbs | Gen. Radomir Putnik (promoted to Vojvoda after the battle) | Ottomans | Gen. Zeki Pasha | Oct 23 1912 | Serbs | ||

| Battle of Kirk Kilisse | Bulgarians | Gen. Radko Dimitriev, Gen. Ivan Fichev | Ottomans | Mahmut Muhtar Pasha | Oct 24 1912 | Bulgarians | ||

| Battle of Pente Pigadia | Ottomans | Esat Pasha | Greeks | Lt. Gen. Konstantinos Sapountzakis | Nov 6-12 1912 | Greeks | ||

| Battle of Prilep | Serbs | Ottomans | Nov 3 1912 | Serbs | ||||

| Battle of Lule-Burgas | Bulgarians | Gen. Radko Dimitriev, Gen. Ivan Fichev | Ottomans | Abdullah Pasha | Oct 28-31 1912 | Bulgarians | ||

| Battle of Merhamli | Bulgarians | Gen. Nikola Genev, Col. Aleksandar Tanev | Ottomans | Mehmed Yaver Pasha (POW) | Nov 26 1912 | Bulgarians | ||

| Battle of Vevi | Greeks | Ottomans | Nov 15 1912 | Ottomans | ||||

| Battle of Bitola | Serbs | Gen. Petar Bojović | Ottomans | Zeki Pasha (Gen.) | Nov 16-19 1912 | Serbs | ||

| Naval Battle of Kaliakra | Bulgarians | Cap. Dimitar Dobrev | Ottomans | Hűseyin Rauf Bey (Rauf Orbay) | 21 Nov 1912 | Bulgarians | ||

| Naval Battle of Elli | Greeks | Rear Adm. Pavlos Kountouriotis | Ottomans | Adm Remzi Bey | Dec 16 1912 | Greeks | ||

| Battle of Bulair | Ottomans | Fethi Bey | Bulgarians | Gen. Georgi Todorov | Jan 26 1913 | Bulgarians | ||

| Battle of Şarköy | Ottomans | Enver Bey | Bulgarians | Gen. Stiliyan Kovachev | 26-28 Jan 1913 | Bulgarians | ||

| Naval Battle of Lemnos | Greeks | Rear Adm. Pavlos Kountouriotis | Ottomans | Jan 18 1913 | Greeks | |||

| Battle of Bizani | Greeks | Crown Prince Constantine | Ottomans | Esat Pasha | Mar 5-6 1913 | Greeks | ||

| Siege of Adrianople | Bulgarians & Serbs | Gen. Georgi Vazov, Gen. Stepa Stepanovic | Ottomans | Gen. Gazi Ṣűkrű Pasha | Mar 11-13 1913 | Bulgarians & Serbs | ||

See also

Notes

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

- ^ Turkish General Staff, Balkan Harbi (1912-1913) 1 Cilt, Harbin Sebepleri, Askeri Hazirliklar ve Osmanli Devletinin Harbi Girisi (Inkinci Baski), (Ankara: Generalkurmay Basimevi, 1993) p.100, as found in Erickson, 2003, p.52.

- ^ Hall, Richard C., The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913: prelude to the First World War, (Routledge, 2000), 16.

- ^ Hall, 18.

- ^ Erickson, 2003, p.70

- ^ Erickson, 2003, p.69

- ^ a b Erickson, 2003, p.329

- ^ Βιβλίο εργασίας 3, Οι Βαλκανικοί Πόλεμοι, ΒΑΛΕΡΙ ΚΟΛΕΦ and ΧΡΙΣΤΙΝΑ ΚΟΥΛΟΥΡΗ, translation by ΙΟΥΛΙΑ ΠΕΝΤΑΖΟΥ, CDRSEE, Thessaloniki 2005, page 120,(Greek). Retrieved from http://www.cdsee.org

- ^ The war correspondence of Leon Trotsky: The Balkan Wars 1912-13, 1980, p.221

- ^ Bismarck's Diplomacy at Its Zenith,Joseph Vincent Fulle, 2005 p.22

- ^ Emile Joseph Dillon, "The Inside Story of the Peace Conference", Ch. XV

- ^ The making of a new Europe, 1981, Hugh Seton-Watson & Christopher Seton-Watson p.116

- ^ Balkan Harbi (1912-1913) (1993). Harbin Sebepleri, Askeri Hazirliklar ve Osmani Devletinin Harbi Girisi. Genelkurmay Basimevi. p. 100.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912-1913, Volume II, Ministry of War 1928, pp. 659-663

- ^ a b c d e Erickson (2003), p. 170 Cite error: The named reference "Erickson2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 16

- ^ a b c Hall (2000), p. 18

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 17

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 70

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 19 Cite error: The named reference "Hall19" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 62

- ^ Hall (2000),p. 22

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 85

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 86

- ^ a b Hall (2000), pp. 22-24 Cite error: The named reference "HallThrace" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912-1913, Volume II Ministry of War 1928, p.660

- ^ a b c Erickson (2003), p. 82

- ^ The rise of nationality in Balkans, R.W. Senton-Watson, 238

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p. 333

- ^ The rise of nationality in Balkans, R.W.Senton-Watson p.202

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p.102

- ^ Hall (2000), p. 32

- ^ The rise of nationality in Balkans, R.W.Senton-Watson, p.235

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 131

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 262

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912-1913, Volume V, Ministry of War 1930, p.1057

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 281

- ^ Turkish General Staff, Edirne Kalesi Etrafindaki Muharebeler, p286

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 281

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912-1913, Volume V, Ministry of War 1930, p.1053

- ^ The rise of nationality in Balkans, R.W.Senton-Watson, p.210-238

- ^ The rise of nationality in Balkans, R.W.Senton-Watson, p.210-238

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 215

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 334

- ^ Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. M. V. Sakellariou. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 9789602133712, p. 367.

- ^ Albania's captives. Pyrros Ruches, Argonaut 1965, p. 65.

- ^ Baker, David, "Flight and Flying: A Chronology", Facts On File, Inc., New York, New York, 1994, Library of Congress card number 92-31491, ISBN 0-8160-1854-5, page 61.

- ^ Hall (2000), p. 65

- ^ Stowell, Ellery Cory (2009). The Diplomacy Of The War Of 1914: The Beginnings Of The War (1915). Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 94. ISBN 978-1104487584.

Sources

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912-1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275978885.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 0415229464.

- Schurman, Jacob Gould (2004). The Balkan Wars 1912 To 1913. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1419153455.