Unicorn: Difference between revisions

added image |

|||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* The [[Invisible Pink Unicorn]] |

* The [[Invisible Pink Unicorn]] |

||

* [[The Unicorns]] |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

Revision as of 07:40, 24 January 2006

The unicorn is a legendary creature embodied like a horse, but slender and with a single — usually spiral — horn growing out of its forehead. Though the popular image of the unicorn is that of a white horse differing only in the horn, the traditional unicorn has a billy-goat beard, a lion's tail, and cloven hoofs, which distinguish him from a horse. Interestingly, these modifications make the horned ungulate more realistic, since only cloven-hoofed animals have horns. Marianna Mayer has observed (The Unicorn and the Lake), "The unicorn is the only fabulous beast that does not seem to have been conceived out of human fears. In even the earliest references he is fierce yet good, selfless yet solitary, but always mysteriously beautiful. He could be captured only by unfair means, and his single horn was said to neutralize poison."

In medieval lore, the alicorn is the spiraled horn of the unicorn and is said to be able to heal and neutralize poisons. This is derived from Ctesias's reports on the unicorn in India, where it was used by the rulers of that place for anti-toxin purposes so as to avoid assassination.

The qilin (麒麟, Chinese), a creature in Chinese myth, is sometimes called "the Chinese unicorn", but it is not directly related to the classical Western unicorn, having the body of a deer, the head of a lion, green scales and a long forth-curved horn. Currently, the word "kirin", in Japan, written with the same Chinese ideograms, is used to designate the giraffe as well as the mythical creature. Curiously, the Japanese mythological creature is usually portrayed as more closely resembling the Western Unicorn than the Chinese qilin, even though based on the Chinese myth.

Unicorns in prehistory

A prehistoric cave painting in Lascaux, France depicts an animal with two straight horns emerging from its forehead. The simple perspective of the painting makes these two horns appear to be a single straight horn; since the species of the figure is otherwise unknown, it has received the moniker "the Unicorn". Richard Leakey suggests that it, like the Sorcerer found at Trois-Frères, is a therianthrope, a blend of animal and human; its head, in his interpretation, is that of a bearded man.[1]

There have been unconfirmed reports of aboriginal paintings of unicorns at Namaqualand in southern Africa. [2]. A passage of Bruce Chatwin's travel journal In Patagonia (1977) relates Chatwin's meeting a South American scientist who believed that unicorns were among South America's extinct megafauna of the Late Pleistocene, and that they were hunted out of existence by man in the 5th or 6th millennium BC. He told Chatwin, who later sought them out, about two aboriginal cave paintings of "unicorns" at Lago Posadas (Cerro de los Indios). One Western legend also speaks of a beautiful young woman named Elly being found by a unicorn, who cried its tears for her and healed the wounds of her heart. Such possibilities, unconfirmed by fossils, would not have affected European legends.

Unicorns in antiquity

According to an interpretation of seals carved with an animal which resembles a bull (and which may in fact be a way of depicting bulls in profile), it has been claimed that the unicorn was a common symbol during the Indus Valley civilization, appearing on many seals. It may have symbolized a powerful group.

An animal called the re'em is mentioned in several places in the Bible, often as a metaphor representing strength; in the King James translation (and some other translations), this word is translated as "unicorn", producing phrases such as "His strength is as the strength of a unicorn". "The allusions to the re'em as a wild, untamable animal of great strength and agility, with mighty horns (Job xxxix. 9-12; Ps. xxii. 21, xxix. 6; Num. xxiii. 22, xxiv. 8; Deut. xxxiii. 17; comp. Ps. xcii. 11), best fit the aurochs (Bos primigenius). This view is supported by the Assyrian rimu, which is often used as a metaphor of strength, and is depicted as a powerful, fierce, wild, or mountain bull with large horns." (Jewish Encyclopedia: "unicorn") This animal was often depicted with only one horn visible in ancient Mesopotamian art.

The unicorn does not appear in early Greek mythology, but in Greek natural history, for Greek writers on natural history were convinced of the reality of the unicorn, which they located in India, a distant and fabulous realm for them. The Encyclopædia Britannica collects classical references to unicorns: the earliest description is from Ctesias, who described in Indica white wild asses, fleet of foot, having on the forehead a horn a cubit and a half in length, colored white, red and black; from the horn were made drinking cups which were a preventive of poisoning. Aristotle must be following Ctesias when he mentions two one-horned animals, the oryx, a kind of antelope, and the so-called "Indian ass" (in Historia anim. ii. I and De part. anim. iii. 2). In Roman times Pliny the Elder's Natural History (viii: 30 and xl: 106) mentions the oryx and an Indian ox (the rhinoceros, perhaps) as one-horned beasts, as well as the Indian ass, "a very ferocious beast, similar in the rest of its body to a horse, with the head of a deer, the feet of an elephant, the tail of a boar, a deep, bellowing voice, and a single black horn, two cubits in length, standing out in the middle of its forehead." Pliny adds that "it cannot be taken alive." Aelian (De natura. anim. iii. 41; iv. 52), quoting Ctesias, adds that India produces also a one-horned horse, and says (xvi. 20) that the "monoceros" was sometimes called carcazonon, which may be a form of the Arabic "carcadn", meaning "rhinoceros". Strabo (book xv) says that in India there were one-horned horses with stag-like heads.

Medieval unicorns

Medieval knowledge of the fabulous beast stems from biblical and ancient sources, and the creature was variously represented as a kind of wild ass, goat, or horse. By A.D. 200, Tertullian had called the unicorn a small fierce kidlike animal, a symbol of Christ. Ambrose, Jerome, and Basil agreed.

The predecessor of the medieval bestiary, compiled in Late Antiquity and known as Physiologus popularized an elaborate allegory in which a unicorn, trapped by a maiden (representing the Virgin Mary) stood for the Incarnation. As soon as the unicorn sees her it lays its head on her lap and falls asleep. This became a basic emblematic tag that underlies medieval notions of the unicorn, justifying its appearance in every form of religious art.

The unicorn was also found in courtly terms: for some 13th century French authors such as Thibaut of Champagne and Richard of Fournival, the lover is as attracted to his lady as the unicorn is to the virgin. This version of salvation provided an alternative to God's love and was called heretical.

With the rise of humanism, the unicorn also acquired positive secular meanings, including chaste love and faithful marriage. It plays this role in Petrarch's Triumph of Chastity. It was a heraldic motif, appearing on the national arms and coins of Scotland. The royal throne of Denmark was made of "unicorn horns" (actually narwhal tusks). The same material was used for ceremonial cups because the unicorn's horn was believed to neutralize poison.

The translators of the King James Version of the Bible (1611) employed unicorn to translate re'em in Book of Job 39:9–12, providing an animal that was proverbial for its untamable nature for the unanswerable rhetorical questions:

"Will the unicorn be willing to serve thee, or abide by thy crib? Canst thou bind the unicorn with band in the furrow? or will he harrow the valleys after thee? Wilt thou trust him, because his strength is great? or wilt thou leave thy labour to him? Wilt thou believe him, that he will bring home thy seed, and gather it into thy barn?"

The unicorn, tamable only by a virgin woman, was well established in medieval lore by the time Marco Polo described them as:

"scarcely smaller than elephants. They have the hair of a buffalo and feet like an elephant's. They have a single large black horn in the middle of the forehead... They have a head like a wild boar's… They spend their time by preference wallowing in mud and slime. They are very ugly brutes to look at. They are not at all such as we describe them when we relate that they let themselves be captured by virgins, but clean contrary to our notions."

It is clear that Polo was describing a rhinoceros.

In German, since the 16th century, the name unicorn ("Einhorn") has become attached to the various rhinoceros.

In popular belief, examined wittily and at length by Sir Thomas Browne in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica unicorn horns could neutralize poisons (book III, ch. xxiii). Therefore, people who feared poisoning sometimes drank from goblets made of "unicorn horn". Alleged aphrodisiac qualities and other purported medicinal virtues also drove up the cost of "unicorn" products such as milk, hide, and offal. Unicorns were also said to be able to determine whether or not a woman was a virgin; in some tales, they could only be mounted by virgins.

One traditional method of hunting unicorns involved entrapment by a virgin. Another involved angering a unicorn, fleeing from it toward a tree when it charged, and diving out of the way just before the tree, causing the unicorn to strike the tree, rendering it dead, unconscious, or stuck, held by its horn in the wood.

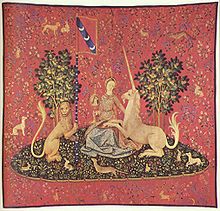

The famous late Gothic series of seven tapestry hangings, The Hunt of the Unicorn is a high point in European tapestry manufacture, combining both secular and religious themes. In the series, richly dressed noblemen, accompanied by huntsmen and hounds, pursue a unicorn against millefleurs backgrounds or buildings and gardens. They bring the animal to bay with the help of a maiden who traps it with her charms, appear to kill it, and bring it back to a castle; in the last and most famous panel, “The Unicorn in Captivity,” the unicorn is shown bloody but now alive and happy, chained to a tree surrounded by a fence, in a field of flowers. Scholars continue to hunt the meaning of the resurrected Unicorn. The series was woven about 1500 in the Low Countries, probably Brussels or Liège, for an unknown patron. A set of six called the Dame á la licorne (Lady with the unicorn) at the Musée de Cluny, Paris, woven in the Southern Netherlands about the same time, pictures the five senses, the gateways to temptation, and finally Love ("A mon seul desir" the legend reads), with unicorns in each hanging.

Heraldry

In heraldry, a unicorn is depicted as a horse with a goat's cloven hooves and beard, a lion's tail, and a slender, spiral horn on its forehead. Whether because it was an emblem of the Incarnation or of the fearsome animal passions of raw nature, the unicorn was not widely used in early heraldry, but became popular from the fifteenth century, usually collared, an indication that its nature had been tempered.

It is probably best known from the royal arms of Scotland and the United Kingdom: two unicorns support the Scottish arms; a lion and a unicorn support the UK arms. The arms of the Society of Apothecaries in London has two golden unicorn supporters.

Sources of the myth

Alleged skeletal evidence

A unicorn skeleton was supposedly found at Einhornhöhle ("Unicorn Cave") in Germany's Harz Mountains in 1663. Claims that the so-called unicorn had only two legs (and was constructed from fossil bones of mammoths and other animals) are contradicted or explained by accounts that souvenir-seekers plundered the skeleton; these accounts further claim that, perhaps remarkably, the souvenir-hunters left the skull, with horn. The skeleton was examined by Leibniz, who had previously doubted the existence of the unicorn, but was convinced thereby.

Baron Georges Cuvier maintained that as the unicorn was cloven-hoofed it must therefore have a cloven skull (making impossible the growth of a single horn), but this was later disproved by Dr. W. Franklin Dove, a University of Maine professor, who artificially fused the horn buds of a calf together, creating a one-horned bull. [3]

P.T. Barnum once exhibited a unicorn skeleton that was exposed as a hoax.

The rhinoceros

Since the rhinoceros is the only land animal to possess a single horn, it has often been supposed that the unicorn legend originated from encounters between Europeans and rhinoceroses. The Woolly Rhinoceros would have been quite familiar to Ice-Age people.

Elasmotherium

One suggestion is that the unicorn myth is based on an extinct animal sometimes called the "Giant Unicorn" but known to scientists as Elasmotherium, a huge Eurasian rhinoceros native to the steppes, south of the range of the woolly rhinoceros of Ice Age Europe. Elasmotherium looked little like a horse, but it had a large single horn in its forehead. It seems to have become extinct about the same time as the rest of the glacial age megafauna, but it may have survived into historic times.

Elasmotherium probably died out in prehistoric times. However, according to the Nordisk familjebok and to space scientist Willy Ley, the animal may have survived long enough to be remembered in the legends of the Evenk people of Russia as a huge black bull with a single horn in the forehead.

There is also a testimony by the medieval traveller Ibn Fadlan, who is usually considered a reliable source, which indicates that Elasmotherium may have survived into historical times.

Ibn Fadlan's account states:

- There is nearby a wide steppe, and there dwells, it is told, an animal smaller than a camel, but taller than a bull. Its head is the head of a ram, and its tail is a bull’s tail. Its body is that of a mule and its hooves are like those of a bull. In the middle of its head it has a horn, thick and round, and as the horn goes higher, it narrows (to an end), until it is like a spearhead. Some of these horns grow to three or five ells, depending on the size of the animal. It thrives on the leaves of trees, which are excellent greenery. Whenever it sees a rider, it approaches and if the rider has a fast horse, the horse tries to escape by running fast, and if the beast overtakes them, it picks the rider out of the saddle with its horn, and tosses him in the air, and meets him with the point of the horn, and continues doing so until the rider dies. But it will not harm or hurt the horse in any way or manner.

- The locals seek it in the steppe and in the forest until they can kill it. It is done so: they climb the tall trees between which the animal passes. It requires several bowmen with poisoned arrows; and when the beast is in between them, they shoot and wound it unto its death. And indeed I have seen three big bowls shaped like Yemen seashells, that the king has, and he told me that they are made out of that animal’s horn.

Even if Elasmotherium is not the source, ordinary rhinoceroses may have some relation to the unicorn. In support of this claim, it has been noted that the 13th century traveller Marco Polo claimed to have seen a unicorn in Java, but his description (quoted above) makes it clear to the modern reader that he actually saw a Javanese rhinoceros.

A mutant goat

The connection that is sometimes made with a single-horned goat derives from the vision of Daniel recorded in Book of Daniel 8:5:

- And as I was considering, behold, a he-goat came from the west over the face of the whole earth, and touched not the ground: and the goat had a notable horn between his eyes.

which is soon exchanged for four horns, as a symbol of a great kingdom giving place to four monarchies.

In the domestic goat, a rare deformity of the generative tissues can cause the horns to be joined together; such an animal could be another possible inspiration for the legend. A farmer and a circus owner also produced fake unicorns, remodelling the "horn buttons" of goat kids, in such a way their horns grew deformed and joined in a grotesque seemingly single horn.[4]

The narwhal

Relics ornamented with supposed unicorn horns can be found in museums in Vienna and elsewhere in central Europe. However, these horns are in fact the spiral tusks of an Arctic cetacean known as the narwhal (Monodon monoceros), as Danish zoologist Ole Worm established in 1638[5]. Presumably they were brought to central Europe as a trade item by Vikings or other northern mariners and sold as genuine unicorn horns, passing the various tests intended to spot fake unicorn horns.

The oryx

The oryx is an antelope with two long, thin horns projecting from its forehead. Some have suggested that seen from the side and from a distance, the oryx looks something like a horse with a single horn (although the 'horn' projects backward, not forward as in the classic unicorn). Conceivably, travellers in Arabia could have derived the tale of the unicorn from these animals. However, classical authors seem to distinguish clearly between oryxes and unicorns.

Fiction

Modern fantasy fiction tends to perpetuate the medieval notion of a unicorn as a beast with magical qualities or powers.

Unicorns notably appear in:

- Piers Anthony's Apprentice Adept series

- Peter S. Beagle's The Last Unicorn

- Terry Brooks's The Black Unicorn

- Bruce Coville's A Glory of Unicorns

- Madeline L'Engle's A Swiftly Tilting Planet and Many Waters

- Timothy Findley's Not Wanted on the Voyage

- Neil Gaiman's Stardust

- C. S. Lewis's The Last Battle

- Anne McCaffrey's Acorna, The Unicorn Girl series.

- J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series

- Ridley Scott's Legend and Blade Runner (movies)

- Roger Zelazny's Amber novels

Although the animal does not appear, unicorn skulls have magical properties in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Haruki Murakami.

See also

External links

- Medieval bestiary: unicorn bibliography

- Jewish Encyclopedia: "Unicorn"

References

- Beer, Rüdiger Robert, Unicorn: Myth and Reality (1977). (Editions: ISBN 0884055833; ISBN 090406915X; ISBN 0442805837.)

- Chatwin, Bruce. 1977. In Patagonia. New York: Summit.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911: "Unicorn"

- Gotfredsen, Lise, The Unicorn (1999). (Editions: ISBN 0789205955; ISBN 1860462677.) A richly illustrated cultural history.