Enoch Powell: Difference between revisions

Tom Morris (talk | contribs) m clean up, replaced: due to the fact that → because using AWB |

m spelling mistake |

||

| Line 293: | Line 293: | ||

Powell wrote an article for ''The Times'' on 29 June in which he said: "The Falklands have brought to he surface of the British mind our latent perception of ourselves as a sea animal...No assault on a landward possession would have evoked the same automatic defiance, tinged with a touch of that self sufficiency which belongs to all nations". The United States' response was "very different but just as deep an instinctual reaction...the United States have an almost neurotic sense of vulnerability...its two coastlines, its two theatres, its two navies are separated by the entire length of the New World...she lives with...the nightmare of having one day to fight a decisive sea battle without the benefit of concentration, the perpetual spectre of naval “war on two fronts”." Powell added: "The Panama Canal from 1914 onwards could never quite exorcise the spectre...It was the position of the Falkland Islands in relation to that route which gave and gives them their significance—for the United States above all. The British people have become uneasily aware that their American allies would prefer the Falkland Islands to pass out of Britain's possession into hands which, if not wholly American, might be amenable to American control. In fact, the American struggle to wrest the islands from Britain has only commenced in earnest now that the fighting is over". Powell then said there was "the Hispanic factor": "If we could gather together all the anxieties for the future which in Britain cluster around race relations...and then attribute them, translated into Hispanic terms, to the Americans, we would have something of the phobias which haunt the United States and addressed itself to the aftermath of the Falklands campaign".<ref>''The Times'' (29 June 1982), p. 10.</ref> |

Powell wrote an article for ''The Times'' on 29 June in which he said: "The Falklands have brought to he surface of the British mind our latent perception of ourselves as a sea animal...No assault on a landward possession would have evoked the same automatic defiance, tinged with a touch of that self sufficiency which belongs to all nations". The United States' response was "very different but just as deep an instinctual reaction...the United States have an almost neurotic sense of vulnerability...its two coastlines, its two theatres, its two navies are separated by the entire length of the New World...she lives with...the nightmare of having one day to fight a decisive sea battle without the benefit of concentration, the perpetual spectre of naval “war on two fronts”." Powell added: "The Panama Canal from 1914 onwards could never quite exorcise the spectre...It was the position of the Falkland Islands in relation to that route which gave and gives them their significance—for the United States above all. The British people have become uneasily aware that their American allies would prefer the Falkland Islands to pass out of Britain's possession into hands which, if not wholly American, might be amenable to American control. In fact, the American struggle to wrest the islands from Britain has only commenced in earnest now that the fighting is over". Powell then said there was "the Hispanic factor": "If we could gather together all the anxieties for the future which in Britain cluster around race relations...and then attribute them, translated into Hispanic terms, to the Americans, we would have something of the phobias which haunt the United States and addressed itself to the aftermath of the Falklands campaign".<ref>''The Times'' (29 June 1982), p. 10.</ref> |

||

Writing in ''The Guardian'' on 18 October Powell asserted that due to the Falklands War "Britain |

Writing in ''The Guardian'' on 18 October Powell asserted that due to the Falklands War "Britain no longer looked upon itself and the world through American spectacles" and the view was "more rational; and it was more congenial; for, after all, it was our own view". He quoted an observation that Americans thought their country was "a unique society...where God has put together all nationalities, races and interests of the globe for one purpose – to show the rest of the world how to live". He denounced the "manic exaltation of the American illusion" and compared it to the "American nightmare". Powell also disliked the American belief that "they are authorised, possibly by the deity, to intervene, openly or covertly, in the internal affairs of other countries anywhere in the world". Britain should dissociate herself from American intervention in the Lebanon: "It is not in Britain's self-interest alone that Britain should once again assert her own position. A world in which the American myth and the American nightmare go unchallenged by question or by contradiction is not a world as safe or as peaceable as human reason, prudence and realism can make it".<ref>Heffer, pp. 861–862.</ref> |

||

Speaking to the Aldershot and North Hants Conservative Association on 4 February 1983, Powell blamed the United Nations for the Falklands War due to the General Assembly resolution of December 1967 which stated "its gratitude for the continuous efforts made by the Government of Argentina to facilitate the process of decolonisation" and further called on Britain and Argentina to negotiate. Powell said "it would be difficult to imagine a more cynically wicked or criminally absurd or insultingly provocative action". As 102 had voted for this resolution with only Britain voting against it (with 32 abstentions), he claimed it was not surprising that Argentina had continually threatened Britain until this threatening turned into aggression: "It is with the United Nations that the guilt lies for the breach of the peace and the bloodshed". The UN knew that no international forum had ruled against British possession of the Falklands but had voted its gratitude to Argentina who wanted to annexe the Islands from their rightful owners. It was therefore "disgraceful" for Britain to belong to such a body that engaged in "pure spite for spite's sake against the United Kingdom": "We were, and are, the victims of our own insincerity. For over thirty years we have sanctimoniously and dishonestly pretended respect, if not awe, for an organisation which all the time we knew was a monstrous and farcical humbug...The moral is to cease to engage in humbug, which almost all have happily and self-righteously engaged in for a generation".<ref>''The Times'' (5 February 1983), p. 2.</ref> |

Speaking to the Aldershot and North Hants Conservative Association on 4 February 1983, Powell blamed the United Nations for the Falklands War due to the General Assembly resolution of December 1967 which stated "its gratitude for the continuous efforts made by the Government of Argentina to facilitate the process of decolonisation" and further called on Britain and Argentina to negotiate. Powell said "it would be difficult to imagine a more cynically wicked or criminally absurd or insultingly provocative action". As 102 had voted for this resolution with only Britain voting against it (with 32 abstentions), he claimed it was not surprising that Argentina had continually threatened Britain until this threatening turned into aggression: "It is with the United Nations that the guilt lies for the breach of the peace and the bloodshed". The UN knew that no international forum had ruled against British possession of the Falklands but had voted its gratitude to Argentina who wanted to annexe the Islands from their rightful owners. It was therefore "disgraceful" for Britain to belong to such a body that engaged in "pure spite for spite's sake against the United Kingdom": "We were, and are, the victims of our own insincerity. For over thirty years we have sanctimoniously and dishonestly pretended respect, if not awe, for an organisation which all the time we knew was a monstrous and farcical humbug...The moral is to cease to engage in humbug, which almost all have happily and self-righteously engaged in for a generation".<ref>''The Times'' (5 February 1983), p. 2.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:39, 29 March 2011

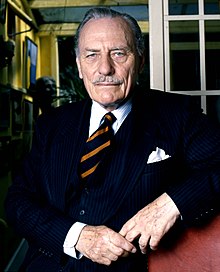

John Enoch Powell | |

|---|---|

Portrait taken by Allan Warren | |

| Minister of Health | |

| In office 27 July 1960 – 18 October 1963 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Derek Walker-Smith |

| Succeeded by | Anthony Barber |

| Financial Secretary to the Treasury | |

| In office 1957–1958 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Henry Brooke |

| Succeeded by | Jack Simon |

| Shadow Defence Secretary | |

| In office July 1965 – 21 April 1968 | |

| Leader | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Peter Thorneycroft |

| Succeeded by | Reginald Maudling |

| Member of Parliament for South Down | |

| In office 10 October 1974 – 11 June 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Lawrence Orr |

| Succeeded by | Eddie McGrady |

| Member of Parliament for Wolverhampton South West | |

| In office 23 February 1950 – 28 February 1974 | |

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Budgen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 June 1912 Birmingham, England |

| Died | 8 February 1998 (aged 85) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative (1950–1974) Ulster Unionist (1974–1987) |

| Spouse(s) | Miss Pamela Wilson, from 1952 to 1998 (46 years) |

| Children | 2 Girls |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge SOAS |

| Occupation | • Member of Parliament 1950–1987 • Conservative Research Department 1945–50 • Professor of Greek at Sydney University 1937–39 |

| Profession | • Politician • Classical scholar, • Poet published works, 1937, 1939, 1951. |

| Awards | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | • Royal Warwickshire Regiment • General Service Corps • Intelligence Corps |

| Years of service | 1939–1945 |

| Rank | • Private in 1939 • Brigadier by 1945 |

| Battles/wars | World War II • North African Campaign • India |

John Enoch Powell, MBE (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, who served as a Conservative Party MP from 1950-1974. He was an early advocate of monetarism and served as Minister of Health (1960–1963) but attained most prominence in 1968, when he made the controversial Rivers of Blood speech, warning on the alleged dangers of mass immigration from Commonwealth nations. For this, he was sacked from his position as Shadow Defence Secretary (1965–1968) in the shadow cabinet of Edward Heath.

However, his supporters claim that the large public following[1][2] which Powell attracted may have helped the Conservatives to win the 1970 General Election,[3] and perhaps cost them the February 1974 General Election [4] at which Powell endorsed a vote for Labour. He returned to the House of Commons in October 1974 as the Ulster Unionist Party MP for the Northern Irish constituency of South Down until he was defeated in the 1987 General Election.

Before entering politics he had been a classical scholar, becoming a full Professor of Ancient Greek at the age of twenty-five. During the Second World War he served in staff and intelligence positions, reaching the rank of brigadier in his early thirties. He was also known for his talents as a writer and a poet.

Early years and education

Enoch Powell was born in Stechford, Birmingham, England. He lived there for the first six years of his life before moving, in 1918, to King's Norton, where he lived until 1930. He was the only child of Albert Enoch Powell (1872–1956), primary school headmaster, and his wife, Ellen Mary (1886–1953). Ellen was the daughter of Henry Breese, a Liverpool policeman and his wife Eliza, who had given up her own teaching career after marrying. The Powells were of Welsh descent, having moved to the developing Black Country during the early 19th century. His great-grandfather was a coal miner, and his grandfather had been employed in the iron trade.[5]

Powell was a pupil at King's Norton Boys' School before moving to King Edward's School, Birmingham, where he studied classics (which would later influence his 'Rivers of Blood' speech), and was one of the few pupils in the school's history to attain 100% in an end-of-year English examination. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1930 to 1933, during which time he fell under the influence both of the poet A. E. Housman, then Professor of Latin at the university, and of the writings of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. He took no part in politics at university.

It was while at Cambridge that Powell is recorded as having enjoyed one of his first close relationships.[6] Indeed, according to John Evans, Chaplain of Trinity and Extra Preacher to the Queen,[7] instructions were left with him to reveal after Powell's death that at least one of the romantic affairs of his life had been homosexual. Powell had particularly drawn the Chaplain's attention to lines in his First Poems (published 1937). Biographers such as Simon Heffer dispute this however, and have argued that this did not mean that he was homosexual; merely that he had not yet met any girls.[8]

Whilst at University, in one Greek prose examination lasting three hours, he was asked to translate a passage into Greek. Powell walked out after one and a half hours, having produced translations in the styles of Plato and Thucydides. For his efforts, he was awarded a double starred first in Latin and Greek, this grade being the best possible and extremely rare. As well as his education at Cambridge, Powell took a course in Urdu at the School of Oriental Studies, now the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, because he felt that his long-cherished ambition of becoming Viceroy of India would be unattainable without knowledge of an Indian language.[8]

Pre-war career

After graduating from Cambridge, Powell stayed on at Trinity College as a Fellow, spending much of his time studying ancient manuscripts in Rome and producing academic works in Greek and Welsh.[9][10] In 1937 he was appointed Professor of Greek at Sydney University aged 25 (failing in his aim of beating Nietzsche's record of becoming a professor at 24). Amongst his pupils was the future Prime Minister of Australia Gough Whitlam. He revised Stuart-Jones's edition of Thucydides' Historiae for the Oxford University Press in 1938, and his most lasting contribution to classical scholarship was his Lexicon to Herodotus, published the same year.

Soon after arrival in Sydney, Australia he was appointed Curator of the Nicholson Museum at Sydney University. He stunned the vice-chancellor by informing him that war would soon begin in Europe, and that when it did he would be heading home to enlist in the army.[11] By the time Powell left King Edward's School in 1930 he had confirmed his instinctive belief that the Armistice was merely temporary and that Britain would be at war with Germany again.[12] During his time in Australia as a professor, he grew increasingly angry at the appeasement of Nazi Germany and what he saw as a betrayal of British national interests. After Neville Chamberlain's first visit to Adolf Hitler at Berchtesgaden Powell wrote in a letter to his parents of 18 September 1938:

I do here in the most solemn and bitter manner curse the Prime Minister of England [sic] for having cumulated all his other betrayals of the national interest and honour, by his last terrible exhibition of dishonour, weakness and gullibility. The depths of infamy to which our accurst "love of peace" can lower us are unfathomable.[13]

In another letter to his parents in June 1939, before the beginning of war, Powell wrote: "It is the English, not their Government; for if they were not blind cowards, they would lynch Chamberlain and Halifax and all the other smarmy traitors".[14] At the outbreak of war, Powell immediately returned to Britain, although not before buying a Russian dictionary, since he thought "Russia would hold the key to our survival and victory, as it had in 1812 and 1916".[15]

War years

During October 1939, almost a month after returning home, Powell enlisted in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as an Australian. During later years he recorded his appointment from private to lance-corporal in his Who's Who entry, on other occasions describing it as a greater promotion than entering the Cabinet. He was trained for a commission after, whilst working in a kitchen, answering the question of an inspecting officer with a Greek proverb. He was commissioned on the General List in 1940, but almost immediately transferred to the Intelligence Corps. During October 1941, as a Lieutenant, Powell was posted to Cairo and transferred back to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He was soon promoted to the rank of Major. He helped plan the attack on Rommel's supply lines, as well as the Battle of El Alamein, and was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in August 1942. The following year, he was honoured as a member of the Order of the British Empire for his military service.

In August 1943, Powell was posted to Delhi. Though he had served in Africa with the Desert Rats, Powell himself never actually experienced combat, serving for most of his military career as a staff officer. It was in Algiers that the beginning of Powell's dislike of the United States was planted. After talking with some senior American officials, he became convinced that one of America's main war aims was to destroy the British Empire. Writing home on 16 February 1943, Powell stated: "I see growing on the horizon the greater peril than Germany or Japan ever were... our terrible enemy, America...."[16] Powell's conviction of the anti-British attitude of the Americans continued during the war. Powell cut out and retained all his life an article from the New Statesman newspaper of 13 November 1943, in which the American Clare Boothe Luce said in a speech that Indian independence would mean that the "USA will really have won the greatest war in the world for democracy".[17]

Powell desperately wanted to go to the Far East to help the fight against Japan because "the war in Europe is won now, and I want to see the Union Flag back in Singapore" before, Powell thought, the Americans beat Britain to it.[18] He attempted to join the Chindits, and jumped into a taxicab to bring the matter up with Orde Wingate,[19] but his duties and rank precluded the assignment.

Having begun the war as the youngest professor in the Commonwealth, Powell ended it as the youngest Brigadier in the British army, one of the very few men of the entire war to rise from Private to Brigadier (another being Fitzroy Maclean). Powell felt guilty for having survived when many of those he had met during his journey through the ranks had not. When once asked how he would like to be remembered, he at first answered "Others will remember me as they will remember me", but when pressed he replied "I should like to have been killed in the war."[20]

Political career

Joining the Conservative Party

Though he voted for the Labour Party in their 1945 landslide victory, because he wanted to punish the Conservative Party for the Munich agreement, after the war he joined the Conservatives and worked for the Conservative Research Department under Rab Butler, where his colleagues included Iain Macleod and Reginald Maudling.[21]

Powell's ambition to be Governor-General of India crumbled in February 1947, when Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that Indian independence was imminent. Powell was so shocked by the change of policy that he spent the whole night after it was announced walking the streets of London.[22] He came to terms with it by becoming fiercely anti-imperialist, believing that once India had gone the whole empire should follow it. This logical absolutism explained his later indifference to the Suez crisis, his contempt for the Commonwealth, and his urging that Britain should end any remaining pretence that it was a world power.

Election to Parliament

After unsuccessfully contesting the Labour Party's ultra-safe seat of Normanton at a by-election in 1947 (when the Labour majority was 62%),[23] he was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Wolverhampton South West in the 1950 general election.

First years as a Backbench MP

On 16 March 1950 Powell made his maiden speech.

On 3 March 1953 Powell spoke against the Royal Titles Bill in the House of Commons. He said he found three major changes to the style of the United Kingdom, "all of which seem to me to be evil". The first one was "that in this title, for the first time, will be recognised a principle hitherto never admitted in this country, namely, the divisibility of the crown". Powell said that the unity of the realm had evolved over centuries and included the British Empire: "It was a unit because it had one Sovereign. There was one Sovereign: one realm". He feared that by "recognising the division of the realm into separate realms, are we not opening the way for that other remaining unity – the last unity of all – that of the person, to go the way of the rest?"[24]

The second change he objected to was "the suppression of the word 'British', both from before the words 'Realms and Territories' where it is replaced by the words 'her other' and from before the word 'Commonwealth', which, in the Statute of Westminster, is described as the 'British Commonwealth of Nations'":

To say that he is Monarch of a certain territory and his other realms and territories is as good as to say that he is king of his kingdom. We have perpetrated a solecism in the title we are proposing to attach to our Sovereign and we have done so out of what might almost be called an abject desire to eliminate the expression 'British'. The same desire has been felt... to eliminate this word before the term 'Commonwealth'.... Why is it, then, that we are so anxious, in the description of our own Monarch, in a title for use in this country, to eliminate any reference to the seat, the focus and the origin of this vast aggregate of territories? Why is it that this 'teeming womb of royal Kings', as Shakespeare called it, wishes now to be anonymous?[25]

Powell claimed that the answer was that because the British Nationality Act 1948 had removed allegiance to the crown as the basis of citizenship and replaced that with nine separate citizenships combined together by statute. Therefore if any of these nine countries became republics the law would not change, as happened with India when it became a republic. Furthermore, Powell went on, the essence of unity was "that all the parts recognise they would sacrifice themselves to the interests of the whole". He denied that there was in India that "recognition of belonging to a greater whole which involves the ultimate consequence in certain circumstances of self-sacrifice in the interests of the whole". Therefore the title 'Head of the Commonwealth', the third major change, was "essentially a sham. They are essentially something which we have invented to blind ourselves to the reality of the position".[26]

These changes were "greatly repugnant" to Powell but:

... if they are changes which were demanded by those who in many wars had fought with this country, by nations who maintained an allegiance to the Crown, and who signified a desire to be in the future as were in the past; if it were our friends who had come to us and said: 'We want this,' I would say: 'Let it go. Let us admit the divisibility of the Crown. Let us sink into anonymity and cancel the word 'British' from our titles. If they like the conundrum 'Head of the Commonwealth' in the Royal style, let it be there'. However, the underlying evil of this is that we are doing it for the sake not of our friends but of those who are not our friends. We are doing this for the sake of those to whom the very names 'Britain' and 'British' are repugnant.... We are doing this for the sake of those who have deliberately cast off their allegiance to our common Monarchy.[27]

For the rest of his life Powell regarded this speech as the finest he ever delivered.[28][29]

In mid-November 1953 Powell secured a place on the 1922 Committee's executive after the third time of trying. Rab Butler also invited him onto the committee which reviewed party policy for the general election, which he attended until 1955.[30] Powell was a member of the Suez Group of MPs who were against the removal of British troops from the Suez Canal because such a move would demonstrate, Powell argued, that Britain could no longer maintain a position there and that any claim to the Suez Canal would therefore be illogical. However, after the troops had left in 1954 and the Egyptians nationalised the Canal in 1956, Powell opposed the British attempts to retake the Canal in the Suez Crisis because he thought the British no longer had the resources to be a world power.[31]

Junior Housing Minister

On 21 December 1955, he was made parliamentary secretary to Duncan Sandys at the Ministry of Housing. Powell called it "the best ever Christmas box".[32] In early 1956 he spoke for the Housing Subsidies Bill in the Commons and argued for the rejection of an amendment that would have hindered slum clearances. He also spoke in support of the Slum Clearances Bill which provided entitlement for full compensation for those who purchased a house after August 1939 and still occupied it in December 1955 if this property would be compulsory purchased by the government if it was deemed unfit for human habitation.[33] In the spring Powell attended a sub-committee on immigration control as a housing minister and advocated immigration controls. In August he gave a speech at a meeting of the Institute of Personnel Management and was asked a question about immigration. He answered that limiting immigration would require a change in the law and "There might be circumstances in which such a change of the law might be the lesser of two evils". But he added: "There would be very few people who would say the time had yet come when it was essential that so great a change should be made". Powell later told Paul Foot that the statement was made "out of loyalty to the Government line".[34] Powell also spoke for the Rent Bill which ended wartime rent controls, but only when existing tenants had moved out, thereby phasing out regulation.[35]

Financial Secretary to the Treasury

At a meeting of the 1922 committee on 22 November Rab Butler made a speech appealing for party unity in the aftermath of the Suez Crisis. His speech did not go down well and Harold Macmillan, whom Butler had taken along for moral support, addressed them and was a great success. In Powell's view this was "one of the most horrible things that I remember in politics...seeing the way in which Harold Macmillan, with all the skill of the old actor-manager, succeeded in false-footing Rab. The sheer devilry of it verged upon the disgusting". After Macmillan's death in 1986 Powell said "Macmillan was a Whig, not a Tory...he had no use for the Conservative loyalties and affections; they interfered too much with the Whig's true vocation of detecting trends in events and riding them skilfully so as to preserve the privileges, property and interests of his class".[36] However when Macmillan replaced Eden as Prime Minister Powell was offered the office of Financial Secretary to the Treasury on 14 January 1957. This office was the Chancellor of the Exchequer's deputy and the most important job outside the Cabinet.[37]

But in January 1958 he resigned, along with the Chancellor of the Exchequer Peter Thorneycroft and his Treasury colleague Nigel Birch, in protest at government plans for increased expenditure; he was a staunch advocate of disinflation, or in modern terms a monetarist, and a believer in market forces.[38] (Powell was also a member of the Mont Pelerin Society.) The by-product of this expenditure was the printing of extra money to pay for it all, which Powell believed to be the cause of inflation, and in effect a form of taxation, as the holders of money find their money is worth less. Inflation rose to 2.5% – a high figure for the era, especially in peacetime.

During the late 1950s Powell promoted control of the money supply to prevent inflation and during the 1960s was an advocate of free market policies which at the time were seen as extreme and unworkable, as well as unpopular. Powell advocated the privatisation of the Post Office and the telephone network as early as 1964, over 20 years before the latter actually took place;[39] and he both scorned the idea of "consensus politics" and wanted the Conservative Party to become a modern businesslike party, freed from its old aristocratic and "old boy network" associations.[40] Perhaps most notably of all, in his 1958 resignation over public spending and what he saw as an inflationary economic policy, he anticipated almost exactly the views that during the 1980s came to be described as "monetarism".[41]

Backbenches

On 27 July 1959 Powell gave his speech on Hola Camp of Kenya, where eleven Mau Mau were killed after refusing work in the camp. Powell noted that some MPs had described the eleven as "sub-human" but Powell responded by saying: "In general, I would say that it is a fearful doctrine, which must recoil upon the heads of those who pronounce it, to stand in judgement on a fellow human being and to say, 'Because he was such-and-such, therefore the consequences which would otherwise flow from his death shall not flow'."[42] Powell also disagreed with the notion that because it was in Africa then different methods were acceptable:

Nor can we ourselves pick and choose where and in what parts of the world we shall use this or that kind of standard. We cannot say, 'We will have African standards in Africa, Asian standards in Asia and perhaps British standards here at home'. We have not that choice to make. We must be consistent with ourselves everywhere. All Government, all influence of man upon man, rests upon opinion. What we can do in Africa, where we still govern and where we no longer govern, depends upon the opinion which is entertained of the way in which this country acts and the way in which Englishmen act. We cannot, we dare not, in Africa of all places, fall below our own highest standards in the acceptance of responsibility.[43]

Denis Healey, MP from 1952 to 1992, later said this speech was "the greatest parliamentary speech I ever heard...it had all the moral passion and rhetorical force of Demosthenes".[44] The Daily Telegraph report of the speech said that "as Mr Powell sat down, he put his hand across his eyes. His emotion was justified, for he had made a great and sincere speech".[45]

Minister of Health

Powell returned to the government in July 1960, when he was appointed Health Minister,[46] albeit outside the Cabinet, but this changed in 1962.[47] During a meeting with parents of babies that had been born with deformities caused by the drug thalidomide, he was unsympathetic to the victims, refusing to meet any babies deformed by the drug and saying that "anyone who took so much as an aspirin put himself at risk." Powell also refused to launch a public inquiry, resisted calls to issue a warning against any left-over thalidomide pills that might remain in people's medicine cabinets (as U.S. President John F. Kennedy had done), and said "I hope you're not going to sue the Government ... No one can sue the Government."[48]

In this job he was responsible for promoting an ambitious ten-year programme of general hospital building and for beginning the neglect of the huge psychiatric institutions. In his famous 1961 "Water Tower" speech, he said:

There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside – the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day. Do not for a moment underestimate their powers of resistance to our assault. Let me describe some of the defences which we have to storm.[49]

The speech catalysed a debate that was one of several strands leading to the Care in the Community initiative of the 1980s. In 1993 however Powell claimed that his policy could have worked but had not. He claimed the criminally insane should have never been released and that the problem was one of funding. He said the new way of caring for the mentally ill would cost more, not less, than the old way because community care was decentralised and intimate as well as being "more human". His successors had not, Powell claimed, provided the money for local authorities to spend on mental health care and therefore institutional care had been neglected whilst at the same time there was not any investment in community care.[50]

Later, he oversaw the employment of a large number of Commonwealth immigrants by the understaffed National Health Service.[51] Prior to this, many non-white immigrants who held full rights of citizenship in Britain were obliged to take the jobs that no one else wanted (e.g. street cleaning, night-shift assembly production lines), often paid considerably less than their white counterparts.[citation needed]

Backbenches

Along with Iain Macleod, Powell refused to serve in the Cabinet following the appointment of Alec Douglas-Home as Prime Minister. This refusal was not based on antipathy to Home personally but was in protest against what Macleod and Powell saw as Macmillan's underhand manipulation of colleagues during the process of choosing a new leader.[52]

During the 1964 general election Powell said in his election address that "in my opinion it was essential, for the sake not only of our own people but of the immigrants themselves, to introduce control over the numbers allowed in. I am convinced that strict control must continue if we are to avoid the evils of a “colour question” in this country, for ourselves and for our children".[53] Norman Fowler, then a reporter for The Times, interviewed Powell during the election and asked him what the biggest issue was: "I expected to be told something about the cost of living but not a bit of it. “Immigration,” replied Enoch. I duly phoned in my piece but it was never used. After all, who in 1964 had ever heard of a former Conservative cabinet minister thinking that immigration was an important political issue?"[53]

Following the Conservatives' defeat in the election, he agreed to return to the front bench as Transport spokesman.[54] In 1965 he stood in the first-ever party leadership election, but came a distant third to Edward Heath, who appointed him Shadow Secretary of State for Defence.[55]

Shadow Defence Secretary

In his first speech to the Conservative Party conference as Shadow Secretary of State for Defence on 14 October 1965, Powell outlined a fresh defence policy, jettisoning what he saw as outdated global military commitments left-over from Britain's imperial past and stressing that Britain was a European power and therefore an alliance with Western European states from possible attack from the East was central to Britain's safety. He defended Britain's nuclear weapons (he did not yet advocate unilateral nuclear disarmament) and argued that it was "the merest casuistry to argue that if the weapon and the means of using it are purchased in part, or even altogether, from another nation, therefore the independent right to use it has no reality. With a weapon so catastrophic, it is possession and the right to use which count".[56] Also, Powell called into question Western military commitments East of Suez:

However much we may do to safeguard and reassure the new independent countries in Asia and Africa, the eventual limits of Russian and Chinese advance in those directions will be fixed by a balance of forces which will itself be Asiatic and African. The two Communist empires are already in a state of mutual antagonism; but every advance or threat of advance by one or the other calls into existence countervailing forces, sometimes nationalist in character, sometimes expansionist, which will ultimately check it. We have to reckon with the harsh fact that the attainment of this eventual equilibrium of forces may at some point be delayed rather than hastened by Western military presence.[57]

The Daily Telegraph journalist David Howell remarked to Andrew Alexander that Powell had "just withdrawn us from East of Suez, and received an enormous ovation because no-one understood what he was talking about".[57] However the Americans were worried by Powell's speech as they wanted British military commitments in South-East Asia as they were still fighting in Vietnam. A transcript of the speech was sent to Washington and the American embassy requested to talk to Heath about the "Powell doctrine". The New York Times said Powell's speech was "a potential declaration of independence from American policy".[58] During the election campaign of 1966 Powell claimed that the British government had contingency plans to send at least a token British force to Vietnam and that, under Labour, Britain "has behaved perfectly clearly and perfectly recognisably as an American satellite". President Johnson had indeed asked Wilson for some British forces for Vietnam, and when it was later suggested to Powell that the view in Washington—that the public reaction to Powell's allegations had made Wilson realise he would not have favourable public opinion and so could not go through with it—Powell responded: "The greatest service I have performed for my country, if that is so".[59] Labour was returned with a large majority, and Powell was retained by Heath as Shadow Defence Secretary as he believed Powell "was too dangerous to leave out".[60]

In a controversial speech on 26 May 1967, Powell criticised Britain's post-war world role:

In our imagination the vanishing last vestiges... of Britain's once vast Indian Empire have transformed themselves into a peacekeeping role on which the sun never sets. Under God's good providence and in partnership with the United States, we keep the peace of the world and rush hither and thither containing Communism, putting out brush fires and coping with subversion. It is difficult to describe, without using terms derived from psychiatry, a notion having so few points of contact with reality.[61]

In 1967, Powell spoke of his opposition to the influx of Kenyan Asians to the United Kingdom after the African country's leader Jomo Kenyatta's discriminatory policies led to the flight of Asians from that country.[62] The biggest argument Powell and Heath had during his time in the Shadow Cabinet was over a dispute on Black Rod. Black Rod would go to the Commons to summon them to the Lords to hear the Royal Assent of Bills. In November 1967 he arrived during a debate on the EEC and was met with cries of "Shame" to "’Op it". At the next Shadow Cabinet meeting Heath said this "nonsense" must be stopped. Powell replied that Heath did not mean it should be ended, surely? He added that did not he realise that the words Black Rod used went back to the 1307 Parliament of Carlisle and were ancient even then? Heath reacted furiously, saying that the British people "were tired of this nonsense and ceremonial and mummery. He would not stand for the perpetuation of this ridiculous business etc.".[63]

"Rivers of Blood" speech

Powell was noted for his oratorical skills, and for being a maverick. On Saturday 20 April 1968 he made a controversial speech in Birmingham, in which he warned his audience of what he believed would be the consequences of continued unchecked immigration from the Commonwealth to Britain. It was an allusion to Virgil towards the end of the speech which has been remembered and gave the speech its common title:

As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see 'the River Tiber foaming with much blood'. That tragic and intractable phenomenon which we watch with horror on the other side of the Atlantic but which there is interwoven with the history and existence of the States itself, is coming upon us here by our own volition and our own neglect. Indeed, it has all but come. In numerical terms, it will be of American proportions long before the end of the century. Only resolute and urgent action will avert it even now.

The Times declared it "an evil speech", stating "This is the first time that a serious British politician has appealed to racial hatred in this direct way in our postwar history."[64]

The main political issue addressed by the speech was not immigration as such, however. It was the introduction by the Labour Government of the Race Relations Act 1968, which Powell found offensive and immoral. The Act would prohibit discrimination on the grounds of race in certain areas of British life, particularly housing, where many local authorities had been refusing to provide houses for immigrant families until they had lived in the country for a certain number of years.

One feature of his speech was the extensive quotation of a letter he claimed to have received detailing the experiences of one of his constituents in Wolverhampton. The writer described the fate of an elderly woman who was supposedly the last white person living in her street. She had repeatedly refused applications from non-whites requiring rooms-to-let, which resulted in her being called a racist outside her home and receiving excrement through her letterbox.

Heath sacked Powell from his Shadow Cabinet the day after the speech, and he never held another senior political post. Powell received almost 120,000 (predominantly positive) letters and a Gallup poll at the end of April showed that 74% of those asked agreed with his speech. After The Sunday Times branded his speeches "racialist", Powell sued it for libel, but withdrew when he was required to provide the letters he had quoted from.

Powell had issued an advance copy of his speech to media personnel and their appearance at the speech may have been because they realised the content was explosive.[65]

During July 1965 he had come third in the Conservative Party leadership contest, obtaining only 15 votes, just below the result Hugh Fraser gained. After the 'Rivers of Blood' speech, however, Powell was transformed into a national public figure and won huge support across Britain. Three days after the speech, on 23 April, as the Race Relations Bill was being debated in the House of Commons, 1,000 dockers marched on Westminster protesting against Powell's "victimisation", and the next day 400 meat porters from Smithfield market handed in a 92-page petition in support of Powell.

"Morecambe Budget"

Powell made a speech in Morecambe on 11 October 1968 on the economy, setting out alternative, radical free-market policies which would later be called the 'Morecambe Budget'. Powell used the financial year of 1968–9 to show how income tax could be halved from 8s 3d to 4s 3d in the pound (basic rate cut from 41% to 21%)[66][67] and how capital gains tax and selective employment tax could be abolished without reducing expenditure on defence or the social services. These tax reductions required a saving of £2,855 million, and this would be funded by eradicating losses in the nationalised industries and denationalising the profit-making state concerns; ending all housing subsidies except for those who could not afford their own housing; ending all foreign aid; ending all grants and subsidies in agriculture; ending all assistance to development areas; ending all investment grants;[68] abolishing the National Economic Development Council and abolishing the Prices and Incomes Board.[69] The cuts in taxation would also allow the state to borrow from the public to spend on capital projects such as hospitals and roads and spend on the firm and humane treatment of criminals.[70]

House of Lords reform

During the summer of 1968 The House of Lords in the Middle Ages was published after 20 years' work. At the press conference for its publication, Powell said if the government introduced a Bill to reform the Lords he would be its "resolute enemy".[71] Later in 1968, when the government published its Bills for the new session, Powell was angry at Heath's acceptance of the plan drawn up by the Conservative MP Iain Macleod and Labour's Richard Crossman to reform the Lords, titled the Parliament (No. 2) Bill.[72] Crossman, opening the debate on 19 November, said the government would reform the Lords in five ways: removing the voting rights of hereditary peers; making sure no party had a permanent majority; in normal circumstances the government of the day would have a working majority; to weaken the Lords' powers to delay laws; and to abolish their power to refuse to consent to subordinate legislation if it had been voted for by the Commons.[73]

Powell spoke in the debate, opposing these plans. He said the reforms were "unnecessary and undesirable" and that there was no weight in the claim that the Lords could "check or frustrate the firm intentions" of the Commons. He claimed that only election or nomination could replace the hereditary nature of the Lords. If they were elected it would pose the dilemma of which House was truly representative of the electorate. He also had another objection: "How can the same electorate be represented in two ways so that the two sets of representatives can conflict and disagree with one another?" Those nominated would be bound to the Chief Whip of their party through a sort of oath and Powell asked "what sort of men and women are they to be who would submit to be nominated to another chamber upon condition that they will be mere dummies, automatic parts of a voting machine?" The inclusion of 30 cross-benchers was "a grand absurdity" because they would have been chosen "upon the very basis that they have no strong views of principle on the way in which the country ought to be governed".[74] Powell claimed the Lords derived their authority not from a strict hereditary system but from its prescriptive nature: "It has long been so, and it works". He then added that there was not any widespread desire for reform: he indicated a recent survey of working-class voters which showed only a third of them wanted to reform or abolish the Lords, with another third believing the Lords were an "intrinsic part of the national traditions of Britain". Powell deduced from this that "As so often the ordinary rank and file of the electorate have seen a truth, an important fact, which has escaped so many more clever people – the underlying value of that which is traditional, that which is prescriptive".[75]

After more speeches against the Bill during early 1969, and with left-wing Labour MPs against Lords reform as well (they wanted abolition), Harold Wilson announced on 17 April that the Bill was being rescinded. Wilson's statement was brief, with Powell intervening: "Don't eat them too quickly", which provoked much laughter in the House.[76] Later that day Powell said in a speech to the Primrose League:

There was an instinct, inarticulate but deep and sound, that the traditional, prescriptive House of Lords posed no threat and injured no interests, but might yet, for all its illogicalities and anomalies, make itself felt on occasion to useful purpose. The same sound instinct was repelled by the idea of a new-fashioned second chamber, artificially constructed by power, party and patronage, to function in a particular way. Not for the first time, the common people of this country proved the surest defenders of their traditional institutions.[76]

Powell's biographer Simon Heffer has described the defeat of Lords reform as "perhaps the greatest triumph of Powell's political career".[76]

During 1969, when it was first suggested that the United Kingdom would join the European Economic Community, Powell spoke openly of his opposition to such a move.

Departure from the Conservative Party

Powell's supporters claim that he contributed to the Conservatives' surprise victory in the 1970 general election, which showed a late surge in Tory support. In "exhaustive research" on the election, the American pollster Douglas Schoen and University of Oxford academic R.W. Johnson believed it "beyond dispute" that Enoch Powell had attracted 2.5 million votes to the Conservatives, although the Tory vote had only increased by 1.7 million since 1966.[3] A February 1969 Gallup poll showed Powell the 'most admired person' in British public opinion.[1] A Daily Express poll in 1972 showed Powell being the most popular politician in the country.[2]

In a defence debate in March 1970 he claimed that "the whole theory of the tactical nuclear weapon, or the tactical use of nuclear weapons, is an unmitigated absurdity" and that it was "remotely improbable" that any group of nations engaged in war would "decide upon general and mutual suicide", and advocated enlargement of Britain's continental army. However when fellow Conservative Julian Amery later in the debate criticised Powell for his anti-nuclear pronouncements, Powell responded: "I have always regarded the possession of the nuclear capability as a protection against nuclear blackmail. It is a protection against being threatened with nuclear weapons. What it is not a protection against is war".[77] However, Powell would later criticise this theory of nuclear deterrence.

Powell had voted against the Schuman plan during 1950 and had supported entry only because he believed that the Common Market was simply a means to secure free trade. During March 1969 he opposed Britain's joining the European Economic Community. Opposition to entry had hitherto been confined largely to the Labour Party but now, he said, it was clear to him that the sovereignty of Parliament was in question, as was Britain's very survival as a nation. This nationalist analysis attracted millions of middle-class Conservatives and others, and as much as anything else made Powell the implacable enemy of Heath, a fervent pro-European, but there was already enmity between the two.

The Conservatives had promised at the 1970 election[78] that in relation to the Common Market "Our sole commitment is to negotiate; no more, no less". When Heath signed an accession treaty before Parliament had even debated the issue, when the second reading of the Bill to put the Treaty into law passed by just eight votes on second reading, and when it became clear that the British people would have no further say in the matter, he declared hostility to his party's line. He voted against the government on every one of the 104 divisions in the course of the European Communities Bill. When finally he lost this struggle, he decided he could no longer sit in a parliament that he believed was no longer sovereign. During the summer of 1972 he prepared to resign, and changed his mind only because of fears of a renewed wave of immigration from Uganda after the accession of Idi Amin, who had expelled Uganda's Asian residents.

During 1972, the same year that he spoke publicly of his opposition to the immigration of Ugandan Asians, Powell was also defeated in his struggle against the European Communities Bill, which helped prepare the United Kingdom to join the common market, which he had spent three years campaigning to prevent from happening.

However, during February 1974 Powell left the Conservative Party, mainly because it had taken the UK into the EEC and because it abandoned its manifesto commitments and he therefore could not advocate it at the election. The monetarist economist Milton Friedman sent Powell a letter praising him as principled.[79] Powell had his friend Andrew Alexander talk with Labour Party leader Harold Wilson's press secretary, Joe Haines, on Powell's timing of his speeches against Heath. Powell had been talking with Wilson irregularly since June 1973 during chance meetings in the gentlemen's toilets of the aye lobby in the House of Commons.[80] Wilson and Haines had ensured that Powell would dominate the newspapers of the Sunday and Monday before election day by having no Labour front bencher give a major speech on 23 February, the day of Powell's speech.[81] Powell gave this speech at the Mecca Dance Hall in the Bull Ring, Birmingham to an audience of 1,500, with some press reports estimating that 7,000 had to be turned away. Powell said the issue of British membership of the EEC was one where "if there be a conflict between the call of country and that of party, the call of country must come first":

Curiously, it so happens that the question 'Who governs Britain?' which at the moment is being frivolously posed, might be taken, in real earnest, as the title of what I have to say. This is the first and last election at which the British people will be given the opportunity to decide whether their country is to remain a democratic nation, governed by the will of its own electorate expressed in its own Parliament, or whether it will become one province in a new European superstate under institutions which know nothing of the political rights and liberties that we have so long taken for granted.[82]

Powell went on to criticise the Conservative Party for obtaining British membership despite promising at the general election that they would "negotiate: no more, no less" and that Britain needed "the full-hearted consent of Parliament and people" if Britain were to join. He also denounced Heath for accusing his political opponents of lacking respect for Parliament whilst being "the first Prime Minister in three hundred years who entertained, let alone executed, the intention of depriving Parliament of its sole right to make the laws and impose the taxes of this country".[83] He then advocated a vote for the Labour Party:

The question is: can they now be prevented from taking back into their own hands the decision about their identity and their form of government which truly was theirs all along? I do not believe they can be prevented: for they are now, at a general election, provided with a clear, definite and practicable alternative, namely, a fundamental renegotiation directed to regain free access to world food markets and recover or retain the powers of Parliament, a renegotiation to be followed in any event by a specific submission of the outcome to the electorate, a renegotiation protected by an immediate moratorium or stop on all further integration of the UK into the Community. This alternative is offered, as such an alternative must be in our parliamentary democracy, by a political party capable of securing a majority in the House of Commons and sustaining a Government.[84]

This call to vote Labour surprised some of Powell's supporters who were more concerned with beating socialism than the loss of national independence.[85] On 25 February he made another speech at Shipley urging a vote for Labour and saying he did not believe the claim that Wilson would renege his commitment to renegotiation, which to Powell was ironic considering Heath's premiership: "In acrobatics Harold Wilson, for all his nimbleness and skill, is simply no match for the breathtaking, thoroughgoing efficiency of the present Prime Minister". At this moment a heckler shouted "Judas!" Powell responded: "Judas was paid! Judas was paid! I am making a sacrifice!"[86] Later in the speech Powell said: "I was born a Tory, am a Tory and shall die a Tory. It is part of me... it is something I cannot alter".[87] During 1987 Powell said there was no contradiction between urging people to vote Labour whilst proclaiming to be a Tory: "Many Labour members are quite good Tories".[88]

Powell, in an interview on 26 February, said he would be voting for Helene Middleweek, the Labour candidate, rather than the Conservative Nicholas Budgen.[89] Powell did not stay up on election night to watch the results on television and when on 1 March Powell picked up his copy of The Times from his letterbox and saw the headline "Mr Heath's general election gamble fails", he reacted by singing the Te Deum. He later said: "I had had my revenge on the man who had destroyed the self-government of the United Kingdom".[90] The election result was a "hung parliament". Although the Tories had won the most votes, Labour finished five seats ahead of the Conservatives. The national swing to Labour was 1 per cent; 4 per cent in Powell's heartland, the West Midlands conurbation; and 16 per cent in his old constituency (although Budgen won the seat).[91] According to Telegraph journalist Simon Heffer, Both Powell and Heath believed that Powell was responsible for the Conservatives losing the election.[91]

Ulster Unionist Party

In a sudden general election in October 1974, Powell returned to Parliament as Ulster Unionist MP for South Down, having rejected an offer to stand as a candidate for the National Front . He repeated his call to vote Labour due to their policy on the EEC.[92]

Since 1968 Powell had been an increasingly frequent visitor to Northern Ireland, and in keeping with his general British nationalist viewpoint he sided strongly with the Ulster Unionists in their desire to remain a constituent part of the United Kingdom. From early 1971 he opposed, with increasing vehemence, Heath's approach to Northern Ireland, the greatest breach with his party coming over the imposition of direct rule in 1972. He was a strong believer in the United Kingdom, and he believed that it would survive only if the Unionists strove to integrate completely with the United Kingdom by abandoning the devolved rule that Northern Ireland had exercised until recently. He refused to join the Orange Institution – the first Ulster Unionist MP at Westminster never to be a member (and to date only one of three, the others being Ken Maginnis and Lady Hermon), and he was an outspoken opponent of the more extremist Unionism espoused by the Reverend Ian Paisley and his supporters.

In the aftermath of the Birmingham pub bombings by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) on 21 November 1974, the government passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act. During its second reading Powell warned of passing legislation "in haste and under the immediate pressure of indignation on matters which touch the fundamental liberties of the subject; for both haste and anger are ill counsellors, especially when one is legislating for the rights of the subject". He said terrorism was a form of warfare which could not be prevented by laws and punishments but by the aggressor's certainty that the war was impossible to win.[93]

When Heath called a leadership election at the end of 1974, Powell claimed they would have to find someone who was not a member of the Cabinet "which, without a single resignation or public dissent, not merely swallowed but advocated every single reversal of election pledge or party principle".[94] During February 1975, after winning the leadership election, Margaret Thatcher refused to offer Powell a Shadow Cabinet place because "he turned his back on his own people" by leaving the Conservative Party exactly 12 months earlier and telling the electorate to vote Labour. Powell replied she was correct to exclude him because, "In the first place I am not a member of the Conservative Party and secondly, until the Conservative Party has worked its passage a very long way it will not be rejoining me".[95] Powell also attributed Thatcher's success to luck, saying that she was faced with "supremely unattractive opponents at the time".[96]

During the 1975 referendum on British membership of the EEC, Powell campaigned for a 'No' vote. However, the electorate voted 'Yes' by a margin of more than two to one. Powell was the second most prominent supporter of the 'No' camp, after Tony Benn.[97]

On 23 March 1977, in a vote of confidence against the minority Labour government, Powell, along with a few other Ulster Unionists, abstained. The government won by 322 votes to 298, and remained in power for another two years.

Powell claimed that the only way to stop the PIRA was for Northern Ireland to be an integral part of the United Kingdom, treated no differently from any other of its constituent parts. He claimed the ambiguous nature of the province's status, with its own parliament and prime minister, gave hope to the PIRA that it could be detached from the rest of the UK:

Every word or act which holds out the prospect that their unity with the rest of the United Kingdom might be negotiable is itself, consciously or unconsciously, a contributory cause to the continuation of violence in Northern Ireland.[98]

Nonetheless in the 1987 general election which he lost, Powell campaigned in Bangor for James Kilfedder, the devolutionist North Down Popular Unionist Party MP, and against Robert McCartney who was standing as a Real Unionist on a policy of integration and equal citizenship for Northern Ireland.[99]

In Powell's later career as an Ulster Unionist MP he continued to criticise the United States, and claimed that the Americans were trying to persuade the British to surrender Northern Ireland into an all-Irish state because the condition for Irish membership of NATO, Powell claimed, was Northern Ireland. The Americans wanted to close the 'yawning gap' in NATO defence that was the southern Irish coast to northern Spain. Powell had a copy of a State Department Policy Statement[100] from 15 August 1950 in which the American government said that the 'agitation' caused by partition in Ireland "lessens the usefulness of Ireland in international organisations and complicates strategic planning for Europe". "It is desirable", the document continued, "that Ireland should be integrated into the defence planning of the North Atlantic area, for its strategic position and present lack of defensive capacity are matters of significance.[101]

Though he voted with the Conservatives in a vote of confidence that brought down the Labour government on 28 March, Powell did not welcome the victory of Margaret Thatcher in the May 1979 election. "Grim" was Powell's response when he was asked what he thought of Thatcher's victory, because he believed she would renege like Heath did in 1972. During the election campaign, Thatcher, when questioned, again repeated her vow that there would be no position for Powell in her cabinet if the Conservatives won the forthcoming general election. Powell wrote to Callaghan after the general election, expressing his sincere sorrow.[citation needed]

After a riot in Bristol in 1980, Powell claimed the media of ignoring similar events in south London and Birmingham and claimed that "Far less than the foreseeable New Commonwealth and Pakistan ethnic proportion would be sufficient to constitute a dominant political force in the United Kingdom able to extract from a government and the main parties terms calculated to render its influence still more impregnable. Far less than this proportion would provide the bases and citadels for urban terrorism, which would in turn reinforce the overt political leverage of simple numbers". He attacked "the false nostrums and promises of those who apparently monopolise the channels of communication. Who then is likely to listen, let alone to respond, to the proof that nothing short of major movements of population can shift the lines along which we are being carried towards disaster?"[102]

In 1980 Powell described the boycott of the Moscow Olympics – following the Russian invasion of Afghanistan – as 'pathetic to the point of farce'.[103] In the 1980s Powell began espousing the policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. In a debate on the nuclear deterrent on 3 March 1981 Powell claimed that the debate was now more political than military; that Britain did not possess an independent deterrent and that through NATO Britain was tied to the nuclear deterrence theory of the United States.[104] In the debate on the address shortly after the general election of 1983, Powell picked up on Thatcher's willingness, when asked, to use nuclear weapons as a "last resort". Powell presented a scenario of what he thought the last resort would be, namely that the Soviet Union would be ready to invade Britain and had used a nuclear weapon on somewhere such as Rockall to demonstrate their willingness to use it:

What would the United Kingdom do? Would it discharge Polaris, Trident or whatever against the main centres of population of the Continent of Europe or in European Russia? If so, what would be the consequence? The consequence would not be that we should survive, that we should repel our antagonist – nor would it be that we should escape defeat. The consequence would be that we would make certain, as far as is humanly possible, the virtual destruction and elimination of the hope of the future in these islands.... I would much sooner that the power to use it was not in the hands of any individual in this country at all.[105]

Powell went on to say that if the Soviet invasion had already begun and Britain resorted to a retaliatory strike the results would be the same: "We should be condemning, not merely to death, but as near as may be the non-existence of our population". To Powell an invasion would take place with or without Britain's nuclear weapons and therefore there was no point in retaining them. He said that after years of consideration he had come to the conclusion that there were no "rational grounds on which the deformation of our defence preparations in the United Kingdom by our determination to maintain a current independent nuclear deterrent can be justified".[106]

On 28 March 1981 Powell gave a speech to Ashton-under-Lyne Young Conservatives where he attacked the "conspiracy of silence" between the government and the opposition over the prospective growth through births of the immigration population and added: "‘We have seen nothing yet’ is a phrase that we could with advantage repeat to ourselves whenever we try to form a picture of that future". He also criticised those who believed it was "too late to do anything" and that "there lies the certainty of violence on a scale which can only adequately be described as civil war".[107] He also said that the solution was "a reduction in prospective numbers as would represent re-emigration hardly less massive than the immigration which occurred in the first place". The Shadow Home Secretary, Labour MP Roy Hattersley, criticised Powell for using "Munich beer-hall language".[108] Then on 11 April occurred a riot in Brixton and when on 13 April Thatcher was quoted Powell's remark that "We have seen nothing yet" by an interviewer she replied: "I heard him say that and I thought it was a very very alarming remark. And I hope with all my heart that it isn't true".[108]

In July a riot took place in Toxteth, Liverpool. On 16 July Powell gave a speech in the Commons in which he said the riots could not be understood unless one takes into consideration the fact that in some large cities between a quarter and a half of those under 25 were immigrant or descended from immigrants. He read out a letter he had received from a member of the public about immigration which included the line: "As they continue to multiply and as we can't retreat further there must be conflict". A Labour MP Martin Flannery intervened, saying Powell was making "a National Front speech". Powell predicted "inner London becoming ungovernable or violence which could only effectively be described as civil war" and Flannery intervened again to ask what Powell knew about inner cities. He replied: "I was a Member for Wolverhampton for a quarter of a century. What I saw in those early years of the development of this problem in Wolverhampton has made it impossible for me ever to dissociate myself from this gigantic and tragic problem". He also criticised the view that the causes of the riots were economic: "Are we seriously saying that so long as there is poverty, unemployment and deprivation our cities will be torn to pieces, that the police in them will be the objects of attack and that we shall destroy our own environment? Of course not". Dame Judith Hart attacked his speech as "an evil incitement to riot". Powell replied: "I am within the judgment of the House, as I am within the judgment of the people of this country, and I am content to stand before either tribunal".[109] After the Scarman Report on the riots was published, Powell gave a speech on 10 December in the Commons. Powell disagreed with Scarman when he said that the black community was alienated because it was economically disadvantaged: the black community was alienated because it was alien. He claimed tensions would worsen because the non-white population was growing: whereas in Lambeth it was 25%, of those of secondary school age it was 40%. Powell said that the government should be honest to the people by telling them in thirty years time the black population of Lambeth would have doubled in size.[110]

John Casey records an exchange between Powell and Thatcher during a meeting of the Conservative Philosophy Group:

Edward Norman (then Dean of Peterhouse) had attempted to mount a Christian argument for nuclear weapons. The discussion moved on to ‘Western values’. Mrs Thatcher said (in effect) that Norman had shown that the Bomb was necessary for the defence of our values. Powell: ‘No, we do not fight for values. I would fight for this country even if it had a communist government.’ Thatcher (it was just before the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands): ‘Nonsense, Enoch. If I send British troops abroad, it will be to defend our values.’ ‘No, Prime Minister, values exist in a transcendental realm, beyond space and time. They can neither be fought for, nor destroyed.’ Mrs Thatcher looked utterly baffled. She had just been presented with the difference between Toryism and American Republicanism.[111]

When Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in April 1982 Powell was given secret briefings on Privy Councillor terms on behalf of his party. On 3 April Powell said in the Commons that the time for inquests on the government's failure to protect the Falkland Islands would come later and that although it was right to put the issue before the United Nations, Britain should wait upon that organisation to deliberate but use forceful action now. He then turned to face Thatcher: "The Prime Minister, shortly after she came into office, received a soubriquet as the “Iron Lady”. It arose in the context of remarks which she made about defence against the Soviet Union and its allies; but there was no reason to suppose that the right hon. Lady did not welcome and, indeed, take pride in that description. In the next week or two this House, the nation and the right hon. Lady herself will learn of what metal she is made".[112] According to Thatcher's friends this had a "devastating impact" on her and encouraged her resolve.[113]

On 14 April in the Commons Powell claimed "it is difficult to fault the military and especially the naval measures which the Government have taken". He added: "We are in some danger of resting our position too exclusively upon the existence, the nature and the wishes of the inhabitants of the Falkland Islands...if the population of the Falkland Islands did not desire to be British, the principle that the Queen wishes no unwilling subjects would long ago have prevailed; but we should create great difficulties for ourselves in other contexts, as well as in this context, if we rested our action purely and exclusively on the notion of restoring tolerable, acceptable conditions and self-determination to our fellow Britons on the Falkland Islands...I do not think that we need be too nice about saying that we defend our territory as well as our people. There is nothing irrational, nothing to be ashamed of, in doing that. Indeed, it is impossible in the last resort to distinguish between the defence of territory and the defence of people". Powell also criticised the United Nations Security Council's resolution calling for a "peaceful solution". He said whilst he wanted a peaceful solution the resolution's meaning "seems to be of a negotiated settlement or compromise between two incompatible positions—between the position which exists in international law, that the Falkland Islands and their dependencies are British sovereign territory and some other position altogether...It cannot be meant that one country has only to seize the territory of another country for the nations of the world to say that some middle position must be found...If that were the meaning of the resolution of the Security Council, the charter of the United Nations would not be a charter of peace; it would be a pirates' charter. It would mean that any claim anywhere in the world had only to be pursued by force, and points would immediately be gained and a bargaining position established by the aggressor".[114]

On 28 April Powell spoke in the Commons against the Northern Ireland Secretary's (Jim Prior) plans for devolution to a power-sharing assembly in Northern Ireland: "We assured the people of the Falkland Islands that there should be no change in their status without their agreement. Yet at the very same time that those assurances were being repeated, the actions of the Government and their representatives elsewhere were belying or contradicting those assurances and showing that part at any rate of the Government was looking to a very different outcome that could not be approved by the people of the islands. Essentially, exactly the same has happened over the years to Northern Ireland". He further claimed that power-sharing was a negation of democracy.[115]

The next day Powell disagreed with the Labour Party leader Michael Foot's claim that the British government was acting under the authority of the United Nations: "The right of self-defence—to repel aggression and to expel an invader from one's territory and one's people whom he has occupied and taken captive—is, as the Government have said, an inherent right. It is one which existed before the United Nations was dreamt of".[116]

On 13 May Powell said the task force was sent "to repossess the Falkland Islands, to restore British administration of the islands and to ensure that the decisive factor in the future of the islands should be the wishes of the inhabitants" but the Foreign Secretary (Francis Pym) desired an "interim agreement": "So far as I understand that interim agreement, it is in breach, if not in contradiction, of each of the three objects with which the task force was dispatched to the South Atlantic. There was to be a complete and supervised withdrawal of Argentine forces...matched by corresponding withdrawal of British forces. There is no withdrawal of British force that “corresponds” to the withdrawal from the territory of the islands of those who have unlawfully occupied them. We have a right to be there; those are our waters, the territory is ours and we have the right to sail the oceans with our fleets whenever we think fit. So the whole notion of a “corresponding withdrawal”, a withdrawal of the only force which can possibly restore the position, which can possibly ensure any of the objectives which have been talked about on either side of the House, is in contradiction of the determination to repossess the Falklands".[117]

After British forces successfully recaptured the Falklands, Powell asked Thatcher in the Commons on 17 June, recalling his statement to her of 3 April: "Is the right hon. Lady aware that the report has now been received from the public analyst on a certain substance recently subjected to analysis and that I have obtained a copy of the report? It shows that the substance under test consisted of ferrous matter of the highest quality, that it is of exceptional tensile strength, is highly resistant to wear and tear and to stress, and may be used with advantage for all national purposes?" She replied that "I think that I am very grateful indeed to the right hon. Gentleman. I agree with every word that he said".[118] Their mutual friend Ian Gow printed and framed this and the original question and presented it to Thatcher, who hung it in her office.[119]

Powell wrote an article for The Times on 29 June in which he said: "The Falklands have brought to he surface of the British mind our latent perception of ourselves as a sea animal...No assault on a landward possession would have evoked the same automatic defiance, tinged with a touch of that self sufficiency which belongs to all nations". The United States' response was "very different but just as deep an instinctual reaction...the United States have an almost neurotic sense of vulnerability...its two coastlines, its two theatres, its two navies are separated by the entire length of the New World...she lives with...the nightmare of having one day to fight a decisive sea battle without the benefit of concentration, the perpetual spectre of naval “war on two fronts”." Powell added: "The Panama Canal from 1914 onwards could never quite exorcise the spectre...It was the position of the Falkland Islands in relation to that route which gave and gives them their significance—for the United States above all. The British people have become uneasily aware that their American allies would prefer the Falkland Islands to pass out of Britain's possession into hands which, if not wholly American, might be amenable to American control. In fact, the American struggle to wrest the islands from Britain has only commenced in earnest now that the fighting is over". Powell then said there was "the Hispanic factor": "If we could gather together all the anxieties for the future which in Britain cluster around race relations...and then attribute them, translated into Hispanic terms, to the Americans, we would have something of the phobias which haunt the United States and addressed itself to the aftermath of the Falklands campaign".[120]