ß: Difference between revisions

Curryfranke (talk | contribs) →Adelung's and Heyse's rules: More exact translation, to explain why the German words are so long: they are compound words. |

|||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

== Similar letters == |

== Similar letters == |

||

===Lowercase beta=== |

===Lowercase beta=== |

||

"ß" should not be confused with the unrelated lower-case [[Greek alphabet|Greek]] letter [[beta (letter)|"β" (beta)]], which the so called [[#Alternative representations |

"ß" should not be confused with the unrelated lower-case [[Greek alphabet|Greek]] letter [[beta (letter)|"β" (beta)]], which the so called [[#Alternative representations in Antiqua|Sulzbacher form]] closely resembles, particularly to the eyes of non-German or non-Greek readers. Any typeset material should use the ß; where that letter is unavailable, the substitution of "ss" for "ß" is correct, and clearly preferable to the use of Greek "β". |

||

The differences between "ß" and "β" in most typefaces are: |

The differences between "ß" and "β" in most typefaces are: |

||

Revision as of 18:24, 29 January 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

In the German alphabet, ß (Unicode U+00DF) is a letter that originated as a ligature of ss or sz. Like double "s", it is pronounced as an [s] (see IPA), but in standard spelling, it is only used after long vowels and diphthongs, while ss is used after short vowels. Its German name is Eszett (IPA: [ʔɛsˈt͡sɛt], lexicalized expression for sz) or scharfes S (IPA: [ˈʃaʁfəs ˈʔɛs, ˈʃaːɐ̯fəs ˈʔɛs], sharp S).

History

Origin of long s and s as ligature in Roman type

In the late 18th and early 19th century, when more and more German texts were printed in Roman type, typesetters looked for a Roman counterpart for the blackletter ſz ligature, which did not exist in Roman fonts. Printers experimented with various solutions, mostly replacing blackletter ß in Roman type with either sz, ss, ſs, or some combination of these. Although there are early examples in Roman type of a ſs-ligature that looks like the letter ß, it was not commonly used as Eszett.[citation needed]

It was only with the First Orthographic Conference in Berlin in 1876 that printers and type foundries started to look for a common letter form to represent the Eszett in Roman type. In 1879, a proposal for various letter forms was published in the Journal für Buchdruckerkunst. A committee of the Typographic Society of Leipzig chose the so-called Sulzbacher Form. In 1903 it was proclaimed as the new standard for the Eszett in Roman type.[1]

Since then, German printing set in Roman type has used the letter ß. The Sulzbacher Form, however, did not find unanimous acceptance. It became the default form, but many type designers preferred (and still prefer) other forms. Some resemble a blackletter sz-ligature, others more a Roman ſs-ligature.

To the reader unfamiliar with German, the ß's "s" origin may be obscure or nearly undetectable, particularly in the Sulzbacher Form. Long s itself was frequently confused with "f," which led to its demise in English writing around 1800. Unlike German, ß per se has apparently never been used in English. Rather, various other forms are seen for ss in pre-modern literature and handwriting. A double long-s [ſſ] is seen in places such as scans of the original Geneva Bible of 1560. Scans of British census sheets of the 19th century may show a simple unligatured long-s short-s or something that looks to the modern eye as a long-ascendered p. Where the latter case is seen, the pre-modern English handwritten p differs from its ſs generally both by the p's shorter ascender as well as the p's bowl being drawn with a space left at the bottom versus the s of the ſs being drawn in more completely at the bottom.

Adelung's and Heyse's rules

Johann Christoph Adelung (1732–1806) and Johann Christian August Heyse (1764–1829) were two German lexicographers who tried to establish consistent rules on the application of the letter s.

In Austria Heyse's rule of 1829 prevailed from 1879 until the second orthographic conference of 1901, where it was decided to prefer Adelung's rule over Heyse's. The German orthography reform of 1996 reintroduced Heyse's variant, yet without the long s.[2]

| Fraktur according to Adelung | Waſſerschloſʒ | Floſʒ | Paſʒſtraſʒe | Maſʒſtab | Grasſoden | Hauseſel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraktur according to Heyse | Waſſerschloſs | Floſʒ | Paſsſtraſʒe | Maſʒſtab | Grasſoden | Hauseſel |

| Antiqua in 19th century | Wasserschloss | Floss | Paſsstrasse | Maſsstab | Grassoden | Hausesel |

| Antiqua in 20th century (Adelung) | Wasserschloß | Floß | Paßstraße | Maßstab | Grassoden | Hausesel |

| Antiqua in 21st century (Heyse) | Wasserschloss | Floß | Passstraße, Pass-Straße |

Maßstab | Grassoden | Hausesel |

| Translation | moated castle | raft | pass road | scale | (grass) sod | domestic donkey |

In order to display its elements correctly, the ligatures of the Fraktur typesetting are not shown. Therefore the modern Antiqua-ß was used for the Latin orthography since the 20th century.

Heyse's argument: Given that "ss" may appear at the end of a word, before a fugue and "s" being a common initial letter for words, "sss" is likely to appear in a large number of cases (the amount of these cases is even higher than all the possible triple consonant cases (e.g. "Dampfschifffahrt") together).[3] Critics point out that a triple "s" in words like "Missstand" feature less readability than spelling it "Mißstand". Even though the second word of a compound does not start with "s", "ß" should be used to improve the readability of the fugue (e.g. "Meßergebnis" over "Messergebnis" and "Meßingenieur" over "Messingenieur").[4]

This problem of Adelung's rule was solved by Heyse who distinguished between the long s ("ſ") and the round s ("s"). Only the round s could finish a word, therefore called terminal s (Schluss-s). The round s also indicates the fugue in compounds. Instead of "Missstand" and "Messergebnis" one wrote "Miſsſtand" and "Meſsergebnis". Back then a special ligature for Heyse's rule was introduced: ſs. Amongst the common ligatures of "ff", "ft", "ſſ" and "ſt", "ſs" and "ſʒ" were two different characters in the Fraktur typesetting if applying Heyse's rule.

Alternative representations in Antiqua

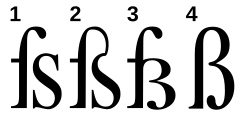

There have been four typographical solutions for the form of the Antiqua ß. Currently, most Antiqua ß are shaped according to the second or the fourth solution. The first and third solution are seldom found.

- letter combination ſs (not as a ligature, but as a single type)

- ligature of ſ and s

- ligature of ſ and a kind of blackletter z that looks similar to an "ʒ" (ezh) or a "3", though it might rather be described as a "Z with a hook" (ȥ) (this solution resembles the original blackletter ligature)

- The Sulzbacher Form

Current usage in German

Since the German spelling reform of 1996, both ß and ss are used to represent /s/ between two vowels as follows:

- ß is used after diphthongs (beißen [ˈbaɪ̯sən] ‘to bite’))

- ß is used after long vowels (grüßen [ˈɡʀyːsən] ‘to greet’)

- ss is used after short vowels (küssen [ˈkʰʏsən] ‘to kiss’)

Thus it helps to distinguish words like Buße (long vowel) 'penance, fine' and Busse (short vowel) 'buses'.

Note that in words where the stem changes, some forms may have an ß but others an ss, for instance sie beißen (‘they bite’) vs. sie bissen (‘they bit’).

The same rules apply at the end of a word or syllable, but are complicated by the fact that single s is also pronounced /s/ in those positions. Thus, words like groß ('large') require ß, while others, like Gras ('grass') use a single s. The correct spelling is not predictable out of context (in standard grammar), but is usually made clear by related forms, e.g., Größe ('size') and grasen ('to graze'), where the medial consonants are pronounced /s/ and /z/ respectively. Many dialects however have an even longer vowel, or an audibly less sharp s, in cases single s is used.

Usage before the spelling reform of 1996

Before the 1996 spelling reform, ß was always used at the end of a word or word-component, or before a consonant, even when the preceding vowel was short. For example, Fuß ('foot') has a long vowel, pronounced /fuːs/, and so was unaffected by the spelling reform; but Kuß ('kiss') has a short vowel, pronounced /kʊs/, and was reformed to Kuss. Other pre-1996 examples included Eßunlust ('loss of appetite'), and wäßrig ('watery'), but Wasser ('water').

The spelling reform affected some German-language forms of foreign place names, such as Rußland ("Russia"), now Russland, and Preßburg ("Bratislava"), now Pressburg.[5] The orthography of personal names (first names and family names) and of names for locations within Germany proper, Austria and Switzerland were not affected by the reform of 1996, however; these names often use irregular spellings that are otherwise impermissible under German spelling rules, not only in the matter of the ß but also in many other respects.

The pre-1996 orthography encouraged the use of SZ in place of ß in words with all letters capitalized where a usual SS would produce an ambiguous result. One possible ambiguity was between IN MASZEN (in limited amounts; Maß, "measure") and IN MASSEN (in massive amounts; Masse, "mass"). Such cases were rare enough that this rule was officially abandoned; however, it is still simply unimaginable for a non-Swiss to enjoy alcohol "in Massen", probably leading to old use where necessary. The German military still occasionally uses the capitalized SZ, even without any possible ambiguity, as SCHIESZGERÄT (“shooting materials”). Architectural drawings may also use SZ in capitalizations because capital letters and both MASZE and MASSE are frequently used. Military teleprinter operation within Germany still uses sz for ß (unlike German typewriters, German teleprinter machines never featured either umlauts or the ß letter).

Substitution and all caps

If no ß is available, ss or sz is used instead. (Sz especially in Hungarian-influenced eastern Austria.) This applies especially to all caps or small caps texts because ß does not have a generally accepted majuscule form. Excepted are all caps names in legal documents; they may retain an ß to prevent ambiguity, e.g., HANS STRAßER.

This ss that replaces an ß had to be hyphenated as a single letter before the 1996 reform. For instance STRA-SSE (‘street’); compare Stra-ße. After the reform, it was hyphenated like other double consonants: STRAS-SE.[6]

Switzerland and Liechtenstein

In Switzerland and Liechtenstein ss usually replaces every ß. This is officially sanctioned by the German orthography rules, which state in §25 E₂: In der Schweiz kann man immer „ss“ schreiben ("In Switzerland, one can always write 'ss'").

The ß has been gradually abolished since the 1930s, when most cantons decided not to teach it anymore and the Swiss postal service stopped using it in place names. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung was the last Swiss newspaper to give up the ß, in 1974. Today, Swiss publishing houses use ß only for books that address the entire German-speaking market.

More recently, ß has experienced a resurgence in use in these countries (as well as Hungary) for informal Internet and SMS communication (similar to the use of k in Italy for ch). For brevity's sake, ß (one character) becomes preferable to German ss or Hungarian sz (two characters). This usage is only passive, because autocompletion programs in mobile phones encourage users to this behaviour.[citation needed]

Upper case

ß is nearly unique among the letters of Latin alphabet in that it had no traditional upper case form. This is because it never occurs initially, and traditional German printing in blackletter never used all-caps.

However, there have been repeated attempts to introduce an upper case ß. Such letterforms can be found in some older German books and some modern signage and product design. Since April 4, 2008 Unicode 5.1.0 has included it ("ẞ") as U+1E9E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S.[7]

Similar letters

Lowercase beta

"ß" should not be confused with the unrelated lower-case Greek letter "β" (beta), which the so called Sulzbacher form closely resembles, particularly to the eyes of non-German or non-Greek readers. Any typeset material should use the ß; where that letter is unavailable, the substitution of "ss" for "ß" is correct, and clearly preferable to the use of Greek "β".

The differences between "ß" and "β" in most typefaces are:

- β reaches below the line while ß does not (except in some italic versions).

- β connects the vertical part on the left with the end of the horizontal near the bottom; ß does not.

- β is often slightly slanted to the right even in upright fonts, while ß is exactly vertical.

However, the reverse substitution of using German "ß" as a surrogate for Greek "β" once was common when describing beta test versions of application programs for older operating systems, whose character encodings, most notably Latin-1 and Windows-1252, did not support easy use of Greek letters. Also, the original IBM DOS code page, CP437 (aka OEM-US) conflates the two characters, assigning them the same codepoint (0xE1) and a glyph that minimises their differences. Though the difference between ß and β is usually obvious in some ornate serif and most sans-serif typefaces (where its "s" origins are more emphasized), a few fonts still use the Sulzbacher design, which renders both characters as near-homoglyphs, the only noticeable difference being the descender on beta: ß β.

Also note: in German handwriting and in Fraktur, the ß is written very similar to β, reaching below the line with the bottom loop connected to the vertical line.

Uppercase B

English speakers unfamiliar with German orthography may also confuse ß with B (the Latin letter which is derived from the Greek beta), which is also incorrect. This effect is used for comic value in the film National Lampoon's European Vacation, where Clark Griswold reads a sign for Dipplestraße as Dipplestrabe.

Keyboards

In Germany and Austria, the letter ß is present on computer and typewriter keyboards, normally to the right on the upper row. In other countries, the letter is not marked on the keyboard, but a combination of other keys can produce it. Often, the letter is input using a modifier and the s key. The details of the keyboard layout depend on the input language and operating system.

- Mac OS X

- Option+s on US, US-Extended, and UK keyboards, Option+b on French keyboard

- Microsoft Windows

- Alt+0223 or Alt+225 or Ctrl+s or (if not used otherwise) Ctrl+Alt+s, on some keyboards such as US-International also AltGr+s

- X-based systems

- AltGr+s or Compose, s, s

- GNU Emacs

- C-x 8 " s

- GNOME

- AltGr+s or Ctrl-Shift-DF or (in GNOME versions 2.15 and later) Ctrl-Shift-U, df

- AmigaOS

- Alt+S for all keymaps on native Amiga keyboards.

- Plan 9

- Alt or Compose, s, s.

- RISC OS

- Alt+s or AltGr+s

The Vim and GNU Screen digraph is ss.

Other languages

'ß' is used by some in romanizing the Sumerian language, to mean 'sh'. Some Sumerian scholars use 'sz' or '$' instead.

It was also in use for Latin during the Medieval and Renaissance time, until the 18th century. E.g.: clarißimus - clarissimus - the brightest; eße - ĕsse - to be; amavißet - amavisset and so on.

'ß' was used to mean 'š' in a German-influenced spelling system for the Lithuanian language which was used in Lithuania Minor in East Prussia: the page section Prussian Lithuanians#Personal names has some examples of Prussian Lithuanian surnames containing 'ß'.

Miscellaneous

In alphabetizing German words, the collation rules say to treat ß as a double "s". Thus, Ruß < Russe < rußen < Russland.

In word processing contexts, ß is sometimes associated with the umlaut, for a purely practical reason: both ß and the umlauted ä, ö, ü are not in ASCII. Thus they tend to cause the same kinds of problems in all sorts of legacy digital text processing applications. Historically, the development of ß is not related to the umlaut, and they are not associated outside of character encoding contexts.

ß is sometimes used in German writing to indicate a pronunciation of /s/ where /z/ would otherwise be usual (in Standard German, initial <s> is pronounced /z/). The novels NeuLand and OstWind by Luise Endlich, for example, use an initial ß to approximate the local dialect in Frankfurt (Oder); thus ßind ßie? ("Sind Sie?").

The HTML entity for ß is ß. Its codepoint in the ISO 8859 character encoding versions 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16 and identically in Unicode is 223, or DF in hexadecimal. In TeX and LaTeX, \ss produces ß.

Also, ß (as well as Ä, Ö, Ü) is widely not considered part of the standard alphabet. If asked how many letters in the alphabet, most Germans would answer 26 instead of 30. Sometimes even 29 may be heard, if it is forgotten that the dots of ä are an old e placed over the vowel, but ß is still remembered as a ligation of sz or ss.

See also

- Capital ß

- Greek letter β (Beta)

- Long s

- Sz (digraph)

- Ȥ

- de:Heysesche s-Schreibung Template:De icon

- de:Adelungsche s-Schreibung Template:De icon

References

- ^ Zeitschrift für Deutschlands Buchdrucker, Steindrucker und verwandte Gewerbe. Leipzig, 9. Juli 1903. Nr. 27, XV. Jahrgang. Faksimile in: Mark Jamra: The Eszett (no date) http://www.typeculture.com/academic_resource/articles_essays/ (checked 17. April 2008)

- ^ Busch, Wolf. "Heysesche s-Schreibung in Frakturschrift" (in German). Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Ickler, Theodor. "Laut-Buchstaben-Zuordnungen". Mein Rechtschreibtagebuch (in German). Forschungsgruppe Deutsche Sprache. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Theodor, Ickler (1997). "Die sogenannte Rechtschreibreform – Ein Schildbürgerstreich" (PDF) (in German). St. Goar: Leibnitz-Verlag. p. 14. ISBN 3-931155-09-9. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ (in German) Wortschatz, Uni Leipzig, Searches for 'Rußland' and 'Preßburg'. Accessed March 20, 2008

- ^ Peter Gallmann (1997): "Warum die Schweizer weiterhin kein Eszett schreiben. Zugleich: Eine Anmerkung zu Eisenbergs Silbengelenk-Theorie". In: Augst, Gerhard; Blüml, Karl; Nerius, Dieter; Sitta, Horst (Eds.) Die Neuregelung der deutschen Rechtschreibung. Begründung und Kritik. Tübingen: Niemeyer (= Reihe Germanistische Linguistik, Vol. 179) pages 135–140.[1], p. 5.

- ^ Unicode 5.1.0

External links

- James Mosley: Eszett or ß - January 31, 2008 on typefoundry.blogspot.com

- Mark Jamra: The Eszett