Leap year: Difference between revisions

→Folk traditions: minor changes |

|||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

==Folk traditions== |

==Folk traditions== |

||

In the British Isles, it is a [[tradition]] that women may [[Proposal of marriage|propose marriage]] only on leap years. While it has been claimed that the tradition was initiated by [[Saint Patrick]] or [[Brigid of Kildare]] in 5th century [[Ireland]], this is dubious, as the tradition has not been attested before the 19th century.<ref>Mikkelson, B. & Mikkelson, D.P. (2010). [http://www.snopes.com/oldwives/february29.asp The Privilege of Ladies by Barbara Mikkelson]. ''The Urban Legends Reference Pages''. snopes.com.</ref> Supposedly, a 1288 law by Queen [[Margaret, Maid of Norway|Margaret of Scotland]] (then age five and living in Norway), required that fines be levied if a marriage proposal was refused by the man; compensation ranged from a kiss to £1 to a silk gown, in order to soften the blow.<ref>Virtually no laws of Margaret survive. Indeed, none concerning her subjects are recorded in the twelve volume ''Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland'' (1814–75) covering the period 1124–1707 (two laws concerning young Margaret herself are recorded on pages 424 & 441–2 of volume I).</ref> In some places the tradition was tightened to restricting female proposals to the modern leap day, February 29, or to the medieval (bissextile) leap day, February 24. |

|||

According to Felten: "A play from the turn of the 17th century, 'The Maydes Metamorphosis,' has it that 'this is leape year/women wear breeches.' A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn't do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat—fair warning, if you will."<ref> |

According to Felten: "A play from the turn of the 17th century, 'The Maydes Metamorphosis,' has it that 'this is leape year/women wear breeches.' A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn't do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat—fair warning, if you will."<ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:16, 16 February 2012

A leap year (or intercalary or bissextile year) is a year containing one extra day (or, in the case of lunisolar calendars, a month) in order to keep the calendar year synchronized with the astronomical or seasonal year.[1] Because seasons and astronomical events do not repeat in a whole number of days, a calendar that had the same number of days in each year would, over time, drift with respect to the event it was supposed to track. By occasionally inserting (or intercalating) an additional day or month into the year, the drift can be corrected. A year that is not a leap year is called a common year.

For example, in the Gregorian calendar (a common solar calendar), February in a leap year has 29 days instead of the usual 28, so the year lasts 366 days instead of the usual 365. Similarly, in the Hebrew calendar (a lunisolar calendar), a 13th lunar month is added seven times every 19 years to the twelve lunar months in its common years to keep its calendar year from drifting through the seasons too rapidly.

Gregorian calendar

In the Gregorian calendar, the current standard calendar in most of the world, most years that are evenly divisible by 4 are leap years. In each leap year, the month of February has 29 days instead of 28. Adding an extra day to the calendar every four years compensates for the fact that a period of 365 days is shorter than a solar year by almost 6 hours.

Some exceptions to this rule are required since the duration of a solar year is slightly less than 365.25 days. Years that are evenly divisible by 100 are not leap years, unless they are also evenly divisible by 400, in which case they are leap years.[2][3] For example, 1600 and 2000 were leap years, but 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not. Similarly, 2100, 2200, 2300, 2500, 2600, 2700, 2900 and 3000 will not be leap years, but 2400 and 2800 will be. Therefore, in a duration of two millennia, there will be 485 leap years. By this rule, the average number of days per year will be 365 + 1/4 − 1/100 + 1/400 = 365.2425, which is 365 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes, and 12 seconds. The Gregorian calendar was designed to keep the vernal equinox on or close to March 21, so that the date of Easter (celebrated on the Sunday after the 14th day of the Moon—i.e. a full moon—that falls on or after March 21) remains correct with respect to the vernal equinox.[4] The vernal equinox year is about 365.242374 days long (and increasing).

The marginal difference of 0.000125 days between the Gregorian calendar average year and the actual year means that, in 8,000 years, the calendar will be about one day behind where it is now. But in 8,000 years, the length of the vernal equinox year will have changed by an amount that cannot be accurately predicted (see below [vague]). Therefore, the current Gregorian calendar suffices for practical purposes, and the correction suggested by John Herschel of making 4000 a non-leap year will probably not be necessary.

This graph shows the variations in date and time of the June Solstice due to unequally spaced 'leap day' rules. See Iranian calendar to contrast with a calendar based on 8 leap days every 33 years. |

Algorithm

Pseudocode to determine whether a year is a leap year or not in either the Gregorian calendar since 1582 or in the proleptic Gregorian calendar before 1582:

if year modulo 4 is 0 then if year modulo 100 is 0 then if year modulo 400 is 0 then is_leap_year else not_leap_year else is_leap_year else not_leap_year

or as a boolean expression

is_leap_year = ( year modulo 4 is 0 ) and ( ( year modulo 100 is not 0 ) or ( year modulo 400 is 0 ) )

Leap day

February 29 is a date that usually occurs every four years, and is called leap day. This day is added to the calendar in leap years as a corrective measure, because the earth does not orbit around the sun in precisely 365 days.

The Gregorian calendar is a modification of the Julian calendar first used by the Romans. The Roman calendar originated as a lunisolar calendar and named many of its days after the syzygies of the moon: the new moon (Kalendae or calends, hence "calendar") and the full moon (Idus or ides). The Nonae or nones was not the first quarter moon but was exactly one nundinae or Roman market week of nine days before the ides, inclusively counting the ides as the first of those nine days. In 1825, Ideler believed that the lunisolar calendar was abandoned about 450 BC by the decemvirs, who implemented the Roman Republican calendar, used until 46 BC. The days of these calendars were counted down (inclusively) to the next named day, so February 24 was ante diem sextum Kalendas Martii ("the sixth day before the calends of March") often abbreviated a. d. VI Kal. Mar. The Romans counted days inclusively in their calendars, so this was actually the fifth day before March 1 when counted in the modern exclusive manner (not including the starting day).[5]

The Republican calendar's intercalary month was inserted on the first or second day after the Terminalia (a. d. VII Kal. Mar., February 23). The remaining days of Februarius were dropped. This intercalary month, named Intercalaris or Mercedonius, contained 27 days. The religious festivals that were normally celebrated in the last five days of February were moved to the last five days of Intercalaris. Because only 22 or 23 days were effectively added, not a full lunation, the calends and ides of the Roman Republican calendar were no longer associated with the new moon and full moon.

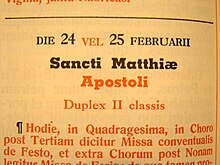

The Julian calendar, which was developed in 46 BC by Julius Caesar, and became effective in 45 BC, distributed an extra ten days among the months of the Roman Republican calendar. Caesar also replaced the intercalary month by a single intercalary day, located where the intercalary month used to be. To create the intercalary day, the existing ante diem sextum Kalendas Martii (February 24) was doubled, producing ante diem bis sextum Kalendas Martii. Hence, the year containing the doubled day was a bissextile (bis sextum, "twice sixth") year. For legal purposes, the two days of the bis sextum were considered to be a single day, with the second half being intercalated, but common practice by 238, when Censorinus wrote, was that the intercalary day was followed by the last five days of February, a. d. VI, V, IV, III and pridie Kal. Mar. (which would be those days numbered 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28 from the beginning of February in a common year), i.e. the intercalated day was the first half of the doubled day. All later writers, including Macrobius about 430, Bede in 725, and other medieval computists (calculators of Easter), continued to state that the bissextum (bissextile day) occurred before the last five days of February.

Until 1970, the Roman Catholic Church always celebrated the feast of Saint Matthias on a. d. VI Kal. Mar., so if the days were numbered from the beginning of the month, it was named February 24 in common years, but the presence of the bissextum in a bissextile year immediately before a. d. VI Kal. Mar. shifted the latter day to February 25 in leap years, with the Vigil of St. Matthias shifting from February 23 to the leap day of February 24. This shift did not take place in pre-Reformation Norway and Iceland; Pope Alexander III ruled that either practice was lawful (Liber Extra, 5. 40. 14. 1). Other feasts normally falling on February 25–28 in common years are also shifted to the following day in a leap year (although they would be on the same day according to the Roman notation). The practice is still observed by those who use the older calendars.

Julian, Coptic and Ethiopian calendars

The Julian calendar adds an extra day to February in years evenly divisible by four.

The Coptic calendar and Ethiopian calendar also add an extra day to the end of the year once every four years before a Julian 29-day February.

This rule gives an average year length of 365.25 days. However, it is 11 minutes longer than a vernal equinox year. This means that the vernal equinox moves a day earlier in the calendar about every 131 years.

Revised Julian calendar

The Revised Julian calendar adds an extra day to February in years divisible by four, except for years divisible by 100 that do not leave a remainder of 200 or 600 when divided by 900. This rule agrees with the rule for the Gregorian calendar until 2799. The first year that dates in the Revised Julian calendar will not agree with those in the Gregorian calendar will be 2800, because it will be a leap year in the Gregorian calendar but not in the Revised Julian calendar..

This rule gives an average year length of 365.242222… days. This is a very good approximation to the mean tropical year, but because the vernal equinox year is slightly longer, the Revised Julian calendar does not do as good a job as the Gregorian calendar of keeping the vernal equinox on or close to March 21.

Chinese calendar

The Chinese calendar is lunisolar, so a leap year has an extra month, often called an embolismic month after the Greek word for it. In the Chinese calendar the leap month is added according to a complicated rule, which ensures that month 11 is always the month that contains the northern winter solstice. The intercalary month takes the same number as the preceding month; for example, if it follows the second month (二月) then it is simply called "leap second month" (simplified Chinese: 闰二月; traditional Chinese: 閏二月; pinyin: rùn'èryuè).

Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar is also lunisolar with an embolismic month. This extra month is called Adar Alef (first Adar) and is added before Adar, which then becomes Adar Bet (second Adar). According to the Metonic cycle, this is done seven times every nineteen years (specifically, in years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 19). This is to ensure that Pesah (Passover) is always in the spring as required by the Torah (Pentateuch) in many verses[6] relating to Pesah.

In addition, the Hebrew calendar has postponement rules that postpone the start of the year by one or two days. These postponement rules reduce the number of different combinations of year length and starting days of the week from 28 to 14, and regulate the location of certain religious holidays in relation to the Sabbath. In particular, the first day of the Hebrew year can never be Sunday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as "lo adu rosh" (לא אד"ו ראש), i.e. "Rosh [ha-Shanah, first day of the year] is not Sunday, Wednesday or Friday" (as the Hebrew word adu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Sunday, Wednesday and Friday). Accordingly, the first day of Pesah (Passover) is never Monday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as "lo badu Pesah" (לא בד"ו פסח), which has a double meaning — "Pesah is not a legend", but also "Pesah is not Monday, Wednesday or Friday" (as the Hebrew word badu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Monday, Wednesday and Friday).

One reason for this rule is that Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Hebrew calendar and the tenth day of the Hebrew year, now must never be adjacent to the weekly Sabbath (which is Saturday), i.e. it must never fall on Friday or Sunday, in order not to have two adjacent Sabbath days. (Ironically, if the belief that man was created on Rosh Hashanah and on Friday are both correct, then the Yom Kippur of that year would have been on a Sunday.) However, Yom Kippur can still be on Saturday.

Years consisting of 12 months have between 353 and 355 days. In a k'sidra ("in order") 354-day year, months have alternating 30 and 29 day lengths. In a chaser ("lacking") year, the month of Kislev is reduced to 29 days. In a malei ("filled") year, the month of Cheshvan is increased to 30 days. 13-month years follow the same pattern, with the addition of the 30-day Adar Alef, giving them between 383 and 385 days.

Islamic calendar

The observed and calculated versions of the Islamic calendar do not have regular leap days, even though both have lunar months containing 29 or 30 days each in no apparent order. However, the tabular Islamic calendar used by Islamic astronomers during the Middle Ages and still used by some Muslims does have a regular leap day added to the last month of the lunar year in 11 years of a 30-year cycle.

Calendars with leap years synchronized with Gregorian

The Indian National Calendar and the Revised Bangla Calendar of Bangladesh organise their leap years so that the leap day is always close to February 29 in the Gregorian calendar. This makes it easy to convert dates to or from Gregorian.

The Bahá'í calendar is structured such that the leap day always falls within Ayyám-i-Há, a period of four or five days corresponding to Gregorian February 26 – March 1. Because of this, Baha'i dates consistently line up with exactly one Gregorian date.

The Thai solar calendar uses the Buddhist Era (BE), but has been synchronized with the Gregorian since AD 1941.

Hindu calendar

In the Hindu calendar, which is a lunisolar calendar, the embolismic month is called adhika maasa (extra month). It is the month in which the sun is in the same sign of the stellar zodiac on two consecutive dark moons. Adhika maasa occurs once every two or three years, compensating for the approximately eleven fewer days per year in twelve lunar months than the solar calendar. Thus, Hindu festivals tend to occur within a given span of the Gregorian calendar. For example: the No Moon during Diwali festival tends to occur between October 22 and November 15. Buddhist calendars in several related forms (each a simplified version of the Hindu calendar) are used on mainland Southeast Asia in the countries of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar (formerly Burma) and Sri Lanka.

The Hindu Calendar also known as Vikram Samvat is used in Nepal as National Calendar. All the official work is done based on this calendar.

The calendar followed in some parts of South India (mainly in Tamil Nadu) is solar. It has a leap year every four years.

Iranian calendar

The Iranian calendar also has a single intercalated day once in every four years, but every 33 years or so the leap years will be five years apart instead of four years apart. The system used is more accurate and more complicated, and is based on the time of the March equinox as observed from Tehran. The 33-year period is not completely regular; every so often the 33-year cycle will be broken by a cycle of 29 or 37 years.[7]

Folk traditions

In the British Isles, it is a tradition that women may propose marriage only on leap years. While it has been claimed that the tradition was initiated by Saint Patrick or Brigid of Kildare in 5th century Ireland, this is dubious, as the tradition has not been attested before the 19th century.[8] Supposedly, a 1288 law by Queen Margaret of Scotland (then age five and living in Norway), required that fines be levied if a marriage proposal was refused by the man; compensation ranged from a kiss to £1 to a silk gown, in order to soften the blow.[9] In some places the tradition was tightened to restricting female proposals to the modern leap day, February 29, or to the medieval (bissextile) leap day, February 24.

According to Felten: "A play from the turn of the 17th century, 'The Maydes Metamorphosis,' has it that 'this is leape year/women wear breeches.' A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn't do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat—fair warning, if you will."[10]

In Denmark, the tradition is that women may propose on the bissextile leap day, February 24, and that refusal must be compensated with 12 pairs of gloves.[11]

In Finland, the tradition is that if a man refuses a woman's proposal on leap day, he should buy her the fabrics for a skirt.[citation needed]

In Greece, marriage in a leap year is considered unlucky.[12] One in five engaged couples in Greece will plan to avoid getting married in a leap year.[13]

Birthdays

A person born on February 29 may be called a "leapling" or a "leaper".[14] In common years they usually celebrate their birthdays on February 28 or March 1. In some situations, March 1 is used as the birthday in a non-leap year since it is the day following February 28.

Technically, a leapling will have fewer birthday anniversaries than their age in years. This phenomenon is exploited when a person claims to be only a quarter of their actual age, by counting their leap-year birthday anniversaries only. In Gilbert and Sullivan's 1879 comic opera The Pirates of Penzance, Frederic the pirate apprentice discovers that he is bound to serve the pirates until his 21st birthday rather than until his 21st year.

For legal purposes, legal birthdays depend on how local laws count time intervals.

Republic of China

The Civil Code of the Republic of China since 10 October 1929[15] implies that the legal birthday of a leapling is February 28 in common years:

If a period fixed by weeks, months, and years does not commence from the beginning of a week, month, or year, it ends with the ending of the day which precedes the day of the last week, month, or year which corresponds to that on which it began to commence. But if there is no corresponding day in the last month, the period ends with the ending of the last day of the last month.[16]

Hong Kong

Since 1990 non-retroactively, Hong Kong considers the legal birthday of a leapling March 1 in common years:

(1) The time at which a person attains a particular age expressed in years shall be the commencement of the anniversary corresponding to the date of his birth.

(2) Where a person has been born on 29 February in a leap year, the relevant anniversary in any year other than a leap year shall be taken to be 1 March.

(3) This section shall apply only where the relevant anniversary falls on a date after the date of commencement of this Ordinance.

Major events

These events are or were held every four years during leap years.

- UEFA European Football Championship

- Summer Olympic Games (1900 was not a leap year)

- Republic of China presidential election, 1996 in Taiwan and subsequent elections

- United States presidential election (1800 and 1900 were not leap years)

- Winter Olympic Games until 1992

See also

- Century leap year

- Leap week calendar

- Leap second

- Zeller's congruence

- Sansculottides

- List of leap years

- Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar

References

- ^ Meeus. Astronomical Algorithms. Willmann-Bell. p. 62. ISBN 0943396611.

- ^ Royal Observatory, Greenwich. (2002). Leap years. Author.

- ^ United States Naval Observatory. (n.d.). Leap Years. Author. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ E.G. Richards, E.G. (1998). Mapping time: The calendar and its history. Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-19-286205-7.

- ^ Thomas Hewitt Key, Calendarium (1875)[dead link]

- ^ Exodus 23,15 ; Exodus 34,18 ; Deuteronomy 15,1 ; Deuteronomy 15, 13

- ^ M. Heydari-Malayeri, A concise review of the Iranian calendar, Paris Observatory, 2004.

- ^ Mikkelson, B. & Mikkelson, D.P. (2010). The Privilege of Ladies by Barbara Mikkelson. The Urban Legends Reference Pages. snopes.com.

- ^ Virtually no laws of Margaret survive. Indeed, none concerning her subjects are recorded in the twelve volume Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1814–75) covering the period 1124–1707 (two laws concerning young Margaret herself are recorded on pages 424 & 441–2 of volume I).

- ^ Felten, E. (February 23, 2008). The bissextile beverage. Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Roberts, S. (March 11, 2011). Denmark + Leap Years. Retrieved March 12, 2011 from https://openlearning.cse.unsw.edu.au/Comp1917/2011s1/discuss/Student/CourseContent/Posts/ToRichardFactAboutDenmarkLeapY.

- ^ A Greek Wedding Anagnosis Books Retrieved 12 January, 2012.

- ^ Teaching Tips 63 Developing Teachers Retrieved 12 January, 2012.

- ^ Hall, C. (February 29, 2008). Leap year babies hop through hoops of joy, pain of novelty birthday. Detroit Free Press. Retrieved February 29, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Legislative history of the Civil Code of the Republic of China now in effect in Taiwan

- ^ Article 121 of the Civil Code Part I General Principles of the Republic of China now in effect in Taiwan

- ^ http://www.legislation.gov.hk/blis_ind.nsf/E1BF50C09A33D3DC482564840019D2F4/22F10EC537B1BEBAC825648300339AA3?OpenDocument Section 5 of the Age of Majority (Related Provisions) Ordinance enacted in 1990

External links