Origins of the American Civil War: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 359: | Line 359: | ||

*[http://www.geocities.com/pes1248 Fields Of Conflict] Collection of source material |

*[http://www.geocities.com/pes1248 Fields Of Conflict] Collection of source material |

||

* American Civil War Research & Discussion Group - [http://groups.yahoo.com/group/FieldsOfConflict/ Fields Of Conflict] - Containing 1500+ Links And 400+ Articles. |

* American Civil War Research & Discussion Group - [http://groups.yahoo.com/group/FieldsOfConflict/ Fields Of Conflict] - Containing 1500+ Links And 400+ Articles. |

||

*[http://antislavery.eserver.org/ Antislavery Literature Project] Contains extensive primary source documents on antebellum history. |

|||

*[http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/civwar.htm Civil War and Reconstruction: Jensen's Guide to WWW Resources] |

*[http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/civwar.htm Civil War and Reconstruction: Jensen's Guide to WWW Resources] |

||

*[http://www.multied.com/elections/1860Pop.html State by state popular vote for president in 1860 election] |

*[http://www.multied.com/elections/1860Pop.html State by state popular vote for president in 1860 election] |

||

Revision as of 19:53, 20 April 2006

The origins of the American Civil War lay in the complex issues of politics, competing understandings of federalism, slavery, expansionism, sectionalism, economics, modernization, and competing nationalism of the Antebellum period. After the Mexican-American War the issue of slavery in the new territories led to the Compromise of 1850. While the Compromise of 1850 averted a political crisis, it did not permanently resolve the issue of the power of slaveholders in national politics. Many Northerners, especially the new Republican Party considered slavery a great national evil, and believed that a small number of Southern owners of large plantations controlled the national government. Southerners denied there was a "slave power conspiracy" and worried instead about the relative political decline of their region as the North grew much faster in terms of population and industrial output. For a chronology of events leading to the American Civil War, see Origins of the American Civil War timeline.

As the North and the South developed divergent societies, two separate regional identities seemed to be emerging. On the eve of the Civil War, the United States was a nation divided into three distinct regions: New England and the Northeast had a rapidly growing industrial and commercial economy and an increasing density of population, fed by large numbers of European immigrants, especially Irish, British and German. The Midwest ("Northwest") was a rapidly expanding region of free farmers tied to the East by railroads, and to the South by the Mississippi riverboats. South had a settled plantation system based on slavery, with rapid growth taking place in Texas. The economic systems were based on free labor in the North and on slave labor in the South.

Moral arguments against slavery had long existed, but, in the interest of maintaining unity, party loyalties had mostly moderated opposition to slavery, resulting in compromises, such as the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850. Heightened moralism meant that people would not compromise their principles. It was all or nothing. The "house divided cannot stand," said Lincoln. Amid the emergence of increasingly virulent and hostile sectional ideologies in national politics, the breakdown of the old Second Party System in the 1850s hampered efforts of the country's politicians to reach sectional compromises. In the 1850s, with the rise of the Republican Party, the nation's first major political party with only sectional appeal, along with its skilled politicians and activists, the industrializing North became committed to the economic ethos of free-labor industrial capitalism. In 1860, the election of Abraham Lincoln, whom slave owners could not abide even though he had married into a slaveowning family, triggered Southern secession from the union.

The rise of anti-slavery

The rise of abolitionism

In the North, anti-slavery movements gained momentum in the 1830s and 1840s, a period of rapid transformation of Northern society that inspired a fervor of social and political reformism. Northern society was experiencing the early stages of industrial development and urbanization, processes that went along with stark changes in American life. Often, reformers were inspired by nostalgia for a bygone era. Nevertheless, many reformers inspired efforts to create or streamline new institutions of social order and control suited to the changing realities of a new era. For example, reform movements were the impetus for the building of prisons and asylums during the era.

To understand the rise of anti-slavery, along with other reform movements of the era, it is thus important to note the context of the changing structures of the American society and economy. The structural changes of the era included the rise of an integrated economic and political structure, the shift from labor-intensive toward capital-intensive production, and the spread of market-oriented capitalist relations. As the Industrial Revolution advanced--not just in the United States, but worldwide--property rights, consumer goods, and laborers were gradually breaking free from the traditional bonds and restraints of their old agrarian societies (e.g., aristocratic traditions, quasi-feudal arrangements, and personalistic and other multi-bonded relations). The socio-economic pressures reaching the surface required a value system viewing continuous social change as natural and desirable. Strongly intertwined with the era's economic development was the growing emphasis of notions of individual liberty, social mobility, and free labor.

The reformers of the 1830s and 1840s provided this emphasis. Many reform movements of the era focused attention in one way or another on a loose set of principles that attempted to transform the lifestyle and work habits of labor, helping workers respond to the new demands of an industrializing, capitalistic society. Their views were strongly anchored in the legacy of the Second Great Awakening, a period of religious revival in the new country stressing the reforms of individuals still relatively fresh in the American memory.

Thus, the principal reform movements in the North were tinged with the Great Awakening ethos of Yankee Protestantism. While including many conflicting ideologies, the reformism of the second quarter of the nineteenth century largely focused on transforming the human personality by internalizing a sense of discipline, order, and restraint. To many reformers, central to the ideal of transforming the human personality was the promise of free labor and upward social mobility (opportunities for advancement, rights to own property, and to control one's own labor), which they considered central to American democracy.

In the 1830s and 1840s, the rise of the anti-slavery movement coincided with the height of Jacksonian democracy, feeding on the same "anti-aristocratic" and egalitarian ethos. Anti-slavery men exalted "free labor," meaning labor working because of incentive instead of coercion, labor with education, skill, the desire for advancement, and also the freedom to move from job to job according to the changing demands of the marketplace. Behind such expectations, the changing economic structures of the era helped to encourage the growing appeal of "free labor" ideals.

The abolitionists of the era shared the fervent enthusiasm for opportunity and "free labor" of other leading reform movements. According to the same principles of self-improvement, industry, and thrift, most abolitionists— William Lloyd Garrison, the most influential among them—condemned slavery as a lack of control over one's own destiny and the fruits of one's labor, but also defined freedom as more than a simple lack of restraint. The truly free man, in the eyes of antebellum reformers, was one who imposed restraints upon himself.

Instead, mainstream abolitionists were more often cordial with reform movements with another vision of society, such as the creation of prisons and asylums, temperance, and relief for the "deserving poor" (with the caveat distinguishing them from the "undeserving poor"). According to most abolitionists and members of related crusades, this was to be done through the purification of society from sins, such as drunkenness, prostitution, ignorance, and--above all--slavery.

The rise of the "free soil" movement

The assumptions, tastes, and cultural aims of the reformers of the thirties and forties anticipated the political and ideological ferment of the 1850s. A surge of working class Irish and German Catholic immigration provoked reactions among many Northern Whigs, as well as Democrats. Growing fears of labor competition for white workers and farmers due to the growing number of free blacks-- known as "Negrophobia"-- prompted several northern states to adopt discriminatory "Black Codes."

In the Northwest, although farm tenancy was increasing, the number of free farmers was still double that of farm laborers and tenants. Moreover, although the expansion of the factory system was undermining the economic independence of the small craftsman and artisan, industry in this region, still one largely of small towns, was still concentrated in small-scale enterprises. Arguably, social mobility was on the verge of contracting in the urban centers of the North, but long-cherished ideas of opportunity, "honest industry," and "toil" were at least close enough in time to lend plausibility to the free labor ideology.

In the rural and small-town North, the picture of Northern society (framed by the ethos of "free labor") corresponded to a large degree with reality. Propelled by advancements in transportation and communication, especially steam navigation, railroads, and telegraphs, the two decades before the Civil War saw the rapid expansion of the population and economy of the Northwest. Combined with the rise of Northeastern and export markets for their products, the social standing of farmers in the region substantially improved. The small towns and villages that emerged as the Republican Party's heartland showed every sign of vigorous expansion. Their vision for an ideal society was of small-scale capitalism, with white American laborers entitled to the chance of upward mobility opportunities for advancement, rights to own property, and to control their own labor. Many free-soilers demanded that the slave labor system and free black settlers (and in places such as California, Chinese immigrants) should be excluded from the Western plains to guarantee the predominance there of the free white laborer.

Opposition to the 1847 Wilmot Proviso helped to consolidate the "free-soil" forces. Next year, Radical New York Democrats known as Barnburners, members of the Liberty Party, and anti-slavery Whigs held a convention at Buffalo, New York in August, forming the Free-Soil party. The party supported former president Martin Van Buren and Charles Francis Adams, Sr. for president and vice president, respectively. The party opposed the expansion of slavery into territories where it had not yet existed, such as Oregon and the ceded Mexican territory.

Relating Northern and Southern positions on slavery to basic differences in labor systems, but insisting on the role of culture and ideology in coloring these differences, Eric Foner's book Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men (1970) went beyond the economic determinism of Charles Beard (a leading historian of the 1930s). Foner emphasized the importance of free labor ideology to Northern opponents of slavery, pointing out that the moral concerns of the abolitionists were not necessarily the dominant sentiments in the North. Many Northerners (including Lincoln) opposed slavery also because they feared that black labor might spread to the North and threaten the position of free white laborers. In this sense, Republicans and the abolitionists were able to appeal to powerful emotions in the North through a broader commitment to "free labor" principles. The "Slave Power" idea had a far greater appeal to Northern self-interest than arguments based on the plight of black slaves in the South. As Frederick Douglass noted, "The cry of Free Man was raised, not for the extension of liberty to the black man, but for the protection of the liberty of the white." If the free labor ideology of the 1830s and 1840s depended on the transformation of Northern society, its entry into politics depended on the rise of mass democracy, in turn propelled by far-reaching social change. Its chance would come by the mid-1850s with the collapse of the traditional two-party system, which had long suppressed sectional conflict.

Sectional tensions and the emergence of mass politics

The politicians of the 1850s were acting in a society in which the traditional restraints that suppressed sectional conflict in the 1820s and 1850s — the most important of which being the stability of the two-party system — were being eroded as this rapid extension of mass democracy went forward in the North.

This was an era when the mass political party galvanized voter participation to an unprecedented degree, and in which politics formed an essential component of American mass culture. Historians specializing in the antebellum years agree that political involvement was a larger concern to the average American in the 1850s than today. With the growth of the American middle class, and rapid growth and change in the economy and society in general, mass participation in politics was much more pronounced, allowing astute politicians to mobilize support by focusing on the expansion of slavery in the West. Politics was, in one of its functions, a form of mass entertainment, a spectacle with rallies, parades, and colorful personalities. Leading politicians, moreover, very often served as a focus for popular interests, aspirations, and values.

Historian Allan Nevins, for instance, writes of political rallies in 1856 with turnouts of anywhere from twenty to fifty thousand men and women. Don E. Fehrenbacher notes that voter turnouts even ran as high as 84 percent for the North by 1860. Religious revivalism reached a new peak in the 1850s. Hysterical fears and paranoid suspicions marked this shift of Americans. The 1850s were fertile ground for propagandists, agitators, and extremists. A plethora of new parties emerged by 1854, including the Republicans, People's party men, Anti-Nebraskaites, Fusionists, Know-Nothings, Know-Somethings (anti-slavery nativists), Maine Lawites, Temperance men, Rum Democrats, Silver Gray Whigs, Hindoos, Hard Shell Democrats, Soft Shells, Half Shells and Adopted Citizens.

Meanwhile, controversy over the so-called Ostend Manifesto (which proposed U.S. annexation of Cuba) and the return of fugitive slaves kept sectional tensions alive before the issue of slavery in the West would preoccupy the country's politics in the mid-to-late fifties. Opposition among some groups in the North intensified after the Compromise of 1850, when Southerners began appearing in Northern states to pursue fugitives or often to claim as slaves free African Americans who had resided there for years. Meanwhile, some abolitionists openly sought to prevent enforcement of the law. Violation of the Fugitive Slave Act was often open and organized. In Boston — a city from which it was boasted that no fugitive had ever been returned — Theodore Parker and other members of the city's elite helped form mobs to prevent enforcement of the law as early as April 1851. A pattern of public resistance emerged in city after city, notably in Syracuse in 1851 (culminating in the Jerry Rescue incident late that year), and Boston again in 1854. But, as mentioned, the issue did not lead to a crisis until revived by the same issue underlying the Missouri Compromise of 1820: slavery in the territories.

It is interesting to note that many Southern states held constitutional conventions in 1851 to consider the questions of nullification and secession. With the exception of South Carolina, whose convention election did not even offer the option of "no secession" but rather "no secession without the collaboration of other states," the Southern conventions were dominated by Unionists who voted down articles of secession. Mississippi's convention even went so far as to deny that the right to secede existed, an extremely interesting position in light of the fact that Mississippi was one of the first states to follow South Carolina's lead in 1861, a scant ten years later.

The question of slavery in the West

Territorial acquisitions

In the 1850s, sectional tensions were revived by the same issue that had produced them dating back to the Missouri Compromise of 1820: slavery in the territories. Northerners and Southerners, in effect, were coming to define "Manifest Destiny" in different ways, undermining nationalism as a unifying force.

By the 1850s, the line of frontier settlement had extended beyond the western boundaries of Iowa, Minnesota, and Missouri to encompass the Great Plains. Just a generation earlier this area had been known as "the Great American Desert," and most Americans had been unaware of the vast areas of arable land beyond the great bend of the Missouri River. Thus, in the states of the Old Northwest (between the Appalachians and the Mississippi) pressure began to build for efforts to extend settlement westward once again. Moreover, on February 2, 1848, Mexico was forced to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding vast tracts of land to the United States. Free Northern farmers did not want to compete against slave labor, thus bringing up debates on whether slavery should be permitted in the newly gained Western territories. Whig politicians did not want the war with Mexico and, as the Wilmot Proviso shows, opposed the extension of slavery in the new lands.

Not only did the territorial acquisitions of the Mexican Cession bring up the old issue of upsetting the balance between slave states and free states in the Senate, they also placed the federal government at the center of sectional conflict. After all, settlers expected something from the federal government: providing territorial governments, and protection from the indigenous population. In addition, the problems of communication and transportation between the older states and areas west of the Mississippi naturally became salient. The interest in further settlement was thus one factor serving to strengthen the federal government. Washington was no longer the remote, unthreatening power that it once had been. It was a power needed to resolve the status of territories and deal directly with sectional disputes.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

The rise of railroads in the 1840s gave added support for those advocating government subsidies to promote transportation. Stephen A. Douglas proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Bill with the intention of building a railroad hub in his home state of Illinois. Douglas—along with many throughout the Mississippi valley—naturally wanted the railroad for his own region, which could allow Chicago to emerge as a great terminal for traffic with the Pacific coast. To garner Southern support, the Kansas-Nebraska Act provided that popular sovereignty, through the territorial legislatures, should decide "all questions pertaining to slavery", thus effectively repealing the Missouri Compromise. While the idea of a transcontinental railroad gained favor in Congress, it quickly became entangled with sectionalism.

Of greater importance than the opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act in Congress was the ensuing public reaction against it in the Northern states. Perhaps no other piece of legislation in congressional history produced so many immediate, sweeping, and ominous changes. It was seen as an effort to repeal the Missouri Compromise, a measure that many Northerners believed had a special sanctity, almost as if it were a part of the Constitution. However, the surprisingly mute popular reaction in the first month after the bill's introduction would fail to foreshadow the gravity of the situation. As Northern papers initially ignored the story, Republican leaders lamented the lack of a popular response.

Eventually, the popular reaction did come, but the leaders had to spark it. Chase's "Appeal of the Independent Democrats" did much to arouse popular opinion. In New York, William Seward finally took it upon himself to organize a rally against the Nebraska bill, since none had arisen spontaneously. Press such as the National Era, the New York Tribune, and local free-soil journals, condemned the bill right away.

The founding of the Republican Party

Convinced that Northern society was superior to that of the South, and increasingly persuaded of the South's ambitions to extend slave power beyond its existing borders, Northerners were embracing a viewpoint that made conflict likely; but conflict required the ascendancy of the Republican Party. The Republican Party – harkening on the popular, emotional issue of "free soil" in the frontier – would capture the White House after just six years of existence, cultivating a coherent ideological message playing on sectional discontent in the rapidly developing North with Democratic leaders.

The Republican Party grew out of the controversy over the Kansas-Nebraska legislation. Once the Northern reaction against the Kansas-Nebraska Act took place, its leaders swung into action to advance another political reorganization. Henry Wilson declared the Whig party dead, and vowed to oppose any efforts to resurrect it. Horace Greeley's Tribune called for the formation of a new Northern party, and Wade, Chase, Sumner, and others spoke out for the union of all opponents of the Nebraska act. The Tribune's Gamaliel Bailey was involved in calling a caucus of anti-slavery Whig and Democratic Party Congressmen in May.

Meeting in a Ripon Wisconsin Congregational Church on February 28, 1854, some thirty opponents of the Nebraska act called for the organization of a new political party and suggested that "Republican" would be the most appropriate name (to link their cause with the Declaration of Independence). These founders also took a leading role in the creation of the Republican Party in many northern states during the summer of 1854. While conservatives and many moderates were content merely to call for the restoration of the Missouri Compromise or a prohibition of slavery extension, radicals advocated repeal of the Fugitive Slave Laws and rapid abolition in existing states. The term "radical" has also been applied to those who objected to the Compromise of 1850, which extended slavery in the territories.

But without the benefit of hindsight, the 1854 elections would seem to indicate the possible triumph of Know-Nothingism rather than anti-slavery, with the Catholic/immigrant question replacing slavery as the issue capable of mobilizing mass appeal. Know-Nothings, for instance, captured the mayoralty of Philadelphia with a majority of over 8,000 votes in 1854. Even after opening up immense discord with his Kansas-Nebraska Act, Senator Douglas began speaking of the Know-Nothings, rather than the Republicans, as the principal danger to the Democratic Party.

After the establishment of the party, when Republicans spoke of themselves as a party of "free labor," they appealed to a rapidly growing, primarily middle class base of support, not permanent wage earners or the unemployed (the working class). When they extolled the virtues of free labor, they were merely reflecting the experiences of millions of men who had "made it" and millions of others who had a realistic hope of doing so. Like the Tories in England, the Republicans in the United States would emerge as the nationalists, homogenizers, imperialists, and cosmopolitans. Intolerant of social diversity, they attempted to impose their values on all groups – including temperance and abolition – while the party of the regional and ethnic minorities (Democrats in America, Liberals in Britain), called for cultural pluralism and local autonomy.

Those who had not yet "made it" included Irish immigrants: a large, growing proportion of Northern factory workers. Republicans often saw the Catholic working class as lacking the qualities of self-discipline, temperance, and sobriety essential for their vision of ordered liberty. Republicans insisted that there was a high correlation between education, religion, and hard work—the values of the "Protestant work ethic"—and Republican votes. "Where free schools are regarded as a nuisance, where religion is least honored and lazy unthrift is the rule," read an editorial of the pro-Republican Chicago Democratic Press after Buchanan's defeat of Frémont in the U.S. presidential election, 1856, "there Buchanan has received his strongest support."

Ethnoreligious, socio-economic, and cultural fault lines ran throughout American society, but were becoming increasingly sectional, pitting Yankee Protestants with a stake in the emerging industrial capitalism and American nationalism increasingly against those tied to Southern slaveholding interests. For example, acclaimed historian Don E. Fehrenbacher, in his Prelude to Greatness, Lincoln in the 1850s, noticed how Illinois was a microcosm of the national political scene, pointing out voting patterns that bore striking correlations to regional patterns of settlement. Those areas settled from the South were staunchly Democratic, while those by New Englanders were staunchly Republican. In addition, a belt of border counties were known for their political moderation, and traditionally held the balance of power. Intertwined with religious, ethnic, regional, and class identities, the issues of free labor and free soil were thus easy to play on.

Events during the next two years in "Bleeding Kansas" sustained the popular fervor originally aroused among some elements in the North by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Those from the North were encouraged by press and pulpit and the powerful organs of abolitionist propaganda. Often they received financial help from such organizations as the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company. Those from the South often received financial contributions from the communities they left. Southerners sought to uphold their constitutional rights in the territories and to maintain sufficient political strength to repulse 'hostile and ruinous legislation.'

While the Great Plains were largely unfit for the cultivation of cotton, informed Southerners demanded that the West be open to slavery, often—perhaps most often—with minerals in mind. Brazil, for instance, was an example of the successful use of slave labor in mining. In the middle of the eighteenth century, diamond mining supplemented gold mining in Minas Gerais and accounted for a massive transfer of masters and slaves from Brazil's Northeastern sugar region. Southern leaders knew a good deal about this experience. It was even promoted in the pro-slavery DeBow's Review as far back as 1848.

"Bleeding Kansas" and the elections of 1856

In Kansas, around 1855, the slavery issue reached a condition of intolerable tension and violence for the first time. But this was in an area where an overwhelming proportion of settlers were merely land-hungry Westerners indifferent to the great public issues looming large in the 1850s. The majority of the inhabitants were not concerned with sectional tensions or the issue of slavery. Instead, the tension in Kansas began as a contention between rival claimants. During the first wave of settlement, no one held titles to the land he was squatting, and settlers rushed to occupy newly open land fit for cultivation. While the tension and violence did emerge as a pattern pitting Yankee and Missourian settlers against each other, there is little evidence of any lofty ideological divides on the questions of slavery. Instead, the Missouri claimants, thinking of Kansas as their own domain--just to the west of their home state, regarded the Yankee squatters as invaders, while the Yankees hated the Missourians for grabbing the best land without honestly settling on it, and stigmatized them as half-savage "pukes."

However, the 1855-56 violence in "Bleeding Kansas" did reach an ideological climax after John Brown— regarded by followers as the instrument of God's will to destroy slavery— entered the melee. His assassination of five proslavery settlers (the so-called "Pottawatomie Massacre", during the night of May 24, 1856) resulted in some irregular, guerrilla-style strife. Aside from John Brown's fervor, the strife in Kansas often involved only armed bands more interested in land claims or loot.

Of greater importance than the civil strife in Kansas, however, was the reaction against it nationwide and in Congress. In both North and South, the belief was widespread that the aggressive designs of the other section were epitomized by (and responsible for) what was happening in Kansas. Whether or not such beliefs were entirely correct is less important than that they became passionately held articles of faith in both sections. Consequently, "Bleeding Kansas" would emerge as a symbol of this sectional controversy.

Even before news of the Kansas skirmishes reached the East coast, a related violent escapade occurred in Washington on May 19 and 20. Charles Sumner's speech before the Senate entitled "The Crime Against Kansas," which condemned the Pierce administration and the institution of slavery, singled out in particular Senator Andrew P. Butler of South Carolina, a strident defender of slavery. Its markedly sexual innuendo cast the South Carolinian as the "Don Quixote" of slavery, who has "chosen a mistress [the harlot slavery]...who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him, though polluted in the sight of the world is chaste in his sight." Several days later, Sumner fell victim to the Southern gentleman's code, which instructed retaliation for impugning the honor of an elderly kinsman. Bleeding and unconsciousness after a nearly fatal assault with a heavy cane by Butler's nephew, U.S. Representative Preston Brooks—and unable to return to the Senate for three years—the Massachusetts Senator emerged as another symbol of sectional tensions. For many in the North, he illustrated the barbarism of slave society.

Indignant over the developments in Kansas, the Republicans—the first entirely sectional major party in U.S. history—entered their first presidential campaign with confidence. Their nominee, John C. Frémont, was a generally safe candidate for the new party. Although his nomination upset some of their Nativist Know-Nothing supporters (his mother was a Catholic), the nomination of the famed explorer of the Far West with no political record was an attempt to woo ex-Democrats. The other two Republican contenders, William Seward and Salmon P. Chase, were seen as too radical.

Nevertheless, the campaign of 1856 was waged almost exclusively on the slavery issue—pitted as a struggle between democracy and aristocracy—focusing on the question of Kansas. The Republicans condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the expansion of slavery, but advanced a program of internal improvements combining the idealism of anti-slavery with the economic aspirations of the North. The new party rapidly developed a powerful partisan culture, and energetically cultivated armies of activists driving voters to the polls in unprecedented numbers. People reacted with fervor. Young Republicans organized the "Wide Awake" clubs and chanted the catchphrase "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men, Frémont!" With Southern fire-eaters and even some moderates uttering threats of secession if Frémont won, the Democratic candidate, Buchanan, benefited from apprehensions about the future of the Union.

Allan Nevins, in his eight-volume Ordeal of the Union, argued that the Civil War was an "irrepressible" conflict. Nevins synthesized contending accounts emphasizing moral, cultural, social, ideological, political, and economic issues. In doing so, he brought the historical discussion back to an emphasis on social and cultural factors. Nevins correctly pointed out that the North and the South were rapidly becoming two different peoples. At the root of these cultural differences was the problem of slavery, but fundamental assumptions, tastes, and cultural aims of the regions were diverging in other ways as well. In many ways, these differences have remained, even into the Twenty-First Century.

The Antebellum South and the Union

Unifying forces

Before the Civil War, a number of factors helped mitigate the sectional tensions, enabling the union to survive episodes such as the Nullification Crisis. The fundamental reason was the dominance of the increasingly pro-Southern Democratic party, which helped secure Southern interests in the federal government.

The Democrats, meanwhile, were the nation's majority party, usually controlling Congress, the presidency, the courts, and many state offices, and the party fostered alliances between Southern planters and Northern Democrats. As a result, until the watershed election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, slaveholders were able to prevail in more and more of the nation's territories and to garner a great deal of influence over national policy.

The expansion of the nation westward made it seem for the time, under President Jackson in the 1830s, that agrarian principles ("Jeffersonian democracy" and "Jacksonian democracy")— in practice an absolute minimum of central authority and a tendency to favor debtors over creditors— had won a permanent victory over those of Alexander Hamilton.

On economic policy, for example, Southerners hailed Jackson's work to dismantle the Bank of the United States, which had been originally introduced in 1791 by Alexander Hamilton as a way of providing for national debt and increasing the power of the federal government. Another example of strong Southern influence was the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which ended the Nullification crisis.[1] Moreover, the South's sway over the judicial branch was perhaps even greater. In 1835, Roger Taney succeeded John Marshall as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. For roughly three decades, the Taney Court asserted the principle of social responsibility for private property— the basis for upholding fugitive slave laws. Finally, even in the realm of foreign policy, the Wilmot Proviso (1847) and the Ostend Manifesto (1854) were examples of strong Southern influence.

Divisive forces

Resistance to centralization and nullification

There had been a continuing contest between the states and the national government over the power of the latter, and over the loyalty of the citizenry, almost since the founding of the republic. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, for example, had defied the Alien and Sedition Acts, and, at the Hartford Convention, New England voiced its opposition to President Madison, the War of 1812, and discussed secession from the Union.

A major and continuous strain on these unifying forces, from roughly 1820 through the Civil War, was the issue of trade and tariffs. Heavily dependent upon trade, the almost entirely agricultural and export-oriented South imported most of its manufactured needs from Europe or obtained them from the North. The North, by contrast, had a growing domestic industrial economy that viewed foreign trade as competition. Trade barriers, especially protective tariffs, were viewed as harmful to the Southern economy, which depended on exports. In 1828, the Congress passed protective tariffs to benefit trade in the northern states, but were detrimental to the South. Southerners vocally expressed their tariff opposition in documents such as the "South Carolina Exposition and Protest" in 1828, written in response to the "Tariff of Abominations."

Having waited four years for Congress to repeal the "Tariff of Abominations," South Carolinians reacted with anger as Congress enacted a new tariff in 1832 that offered them little relief, resulting in the most dangerous sectional crisis since the Union was formed. Some militant South Carolinians even hinted at withdrawing from the Union in response. The state's leading statesman, John C. Calhoun, however, persuaded the most ardent opponents of the tariff to adopt the doctrine of nullification — not secession — as their strategy. The newly elected South Carolina legislature then quickly called for the election of delegates to a state convention. Once assembled, the convention voted to declare null and void the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 within the state. President Andrew Jackson responded firmly, declaring nullification an act of treason. He then took steps to strengthen federal forts in the state.

Violence seemed a real possibility early in 1833 as Jacksonians in Congress were introducing a "force bill" authorizing the president to use the army and navy in order to enforce acts of Congress. No other state had come forward to support South Carolina; and the state itself was divided on willingness to continue the showdown with the federal government. The crisis ended when Henry Clay and Calhoun worked to devise a compromise tariff. Both sides later claimed victory. Calhoun and his supporters in South Carolinia claimed a victory for nullification, insisting that it, a single state, had forced the revision of the tariff. Jackson's followers, however, saw the episode as a demonstration that no single state could assert its rights by independent action. Calhoun, in turn, devoted his efforts to building up a sense of Southern solidarity so that when another standoff should come, the whole section might be prepared to act as a bloc in resisting the federal government.

South Carolina dealt with the tariffs by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within South Carolina state borders. The legislature also passed laws to enforce the ordinance, including authorization for raising a military force and appropriations for arms. In response to South Carolina's threat, Congress passed a "Force Bill" and President Andrew Jackson sent seven naval vessels and a man-of-war into Charleston harbor in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers.

The issue appeared again after 1842's Black Tariff. A period of relative free trade after 1846's Walker Tariff reduction followed until 1860, when the protectionist Morrill Tariff was introduced by the Republicans, fueling Southern anti-tariff sentiments once again.

Diverging cultures

On the slavery issue, growing free labor movements in the North were seen as threats to the Southern plantation system. At the center of these tensions were differences in the labor system. The plantation system, in effect, determined the structure of Southern society. By 1850, there may have been fewer than 350,000 slaveholders in a total free population of about six million--representing approximately 36 percent of white households. There was sufficient social mobility in free southern society that an even larger proportion of free southerners might expect at some point to own slaves. However, the proportion of slaveowning households would decline, by 1860, to approximately 25 percent, and the distribution of slave ownership was highly concentrated within a small minority of slaveowners that owned the majority of slaves. Perhaps seven percent of slaveholders owned roughly three-quarters of the slave population. This plantation-owning elite, known as "slave magnates," was small enough as to be comparable to the millionaires of the following century. Poor whites or "plain folk" (who resorted at times to eating clay) were outside the market economy. Many of the small farmers with a few slaves and yeomen were on its periphery.[2]

Although those who had a proprietary interest in slavery (i.e. the plantation and slave owners) were a very small minority, slave labor was not on the brink of internal collapse due to any moves for democratic change initiated from the region itself. Small free farmers in the South generally accepted the political leadership of the slave magnates and embraced hysterical racism; they were thus unlikely agents for internal democratic reforms in the South.[3] Moreover, even poor whites and "plain folk" would often rally to the cause of slavery's most militant defenders. In the economy, small farmers depended on local planter elites for access to cotton gins, for markets for their feed and livestock, and for loans. In many areas, there were also extensive networks of kinship linking whites of varying social castes. The poorest resident of a county might easily be a cousin of the richest aristocrat, thus explaining why the South would come to defend its "peculiar" institution as the cornerstone of its way of life. Many non-slaveowners also perceived a possibility that they, too, might own slaves at some point in their life.[4]

By the 1850s, Southern slaveholders felt increasingly encircled psychologically and politically. Increasingly dependent on the North for manufactured goods, for commercial services, and for loans, and increasingly cut off from the flourishing agricultural regions of the Northwest, they now faced the prospects of a growing free labor and abolitionist movement in the North.

The militant defense of slavery

With the outcry over developments in Kansas strong in the North, defenders of slavery— increasingly committed to a way of life that much of the rest of the nation considered obsolete or immoral— shifted to a militant pro-slavery ideology that would lay the groundwork for secession upon the emergence of Lincoln.

Southerners waged a vitriolic response to political change in the North. Slaveholding interests sought to uphold their constitutional rights in the territories and to maintain sufficient political strength to repulse "hostile" and "ruinous" legislation.

Behind this shift was the growth of the cotton industry, which left slavery more important than ever to the Southern economy. Coloring this shift and heightening its intensity, it was imbued with a pattern of ideological response and counter-response between the two sections.

Reactions to the popularity of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1851), and the growth of the abolitionist movement (pronounced after the founding of the Liberator in 1831 by William Lloyd Garrison) inspired an elaborate intellectual defense of slavery. Increasingly vocal (and sometimes violent) abolitionist movements, culminating in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 were viewed as a serious threat and, in the minds of many Southerners, abolitionists were attempting to foment violent slave revolts as seen in Haiti in the 1790s and as attempted by Nat Turner some three decades prior.

J. D. B. DeBow established De Bow's Review in 1846, It grew to became the leading Southern magazine, warning the planter class about the dangers of depending on the North economically. De Bow's Review also emerged as the leading voice for secession. The magazine emphasized the South's economic inequality, relating it to the concentration of manufacturing, shipping, banking, and international trade in the North. Frantically searching for Biblical passages endorsing slavery, and conjuring up economic, sociological, historical, and scientific arguments, slavery went from being a "necessary evil" to a "positive good." Foreshadowing modern totalitarian thought, especially Nazism, Dr. J.H. Van Evrie's book Negroes and Negro slavery: The First an Inferior Race: The Latter Its Normal Condition — setting out the arguments the title would suggest — was an attempt to apply scientific analysis.

Latent sectional divisions suddenly activated derogatory sectional imagery, which would emerge into full-blown sectional ideologies. As industrial capitalism gained momentum in the North, Southern writers emphasized whatever aristocratic traits they valued (but often did not practice) in their own society: courtesy, grace, chivalry, the slow pace of life, orderly life, and leisure. This supported their argument that slavery provided a more humane society than industrial labor. The most influential exponent of this argument was undoubtedly George Fitzhugh. In his Cannibals All!, Fitzhugh argued that the antagonism between labor and capital in a free society would result in "robber barons" and "pauper slavery," while in a slave society such antagonisms were avoided. He advocated enslaving Northern factory workers, for their own benefit. Lincoln, on the other hand, denounced such Southern insinuations that Northern wage earners were fatally fixed in that condition for life. To free soilers, the stereotype of the South was one of a diametrically opposite, static society in which the slave system maintained an entrenched anti-democratic aristocracy.

The fragmentation of the American party system

The strains of the Dred Scott decision and the Lecompton constitution

Before the Civil War, the stability of the two-party system was traditionally a unifying force. In the past, the old party-system created links and alliances between parochial interests and political networks of elites in various parts of the country, and kept divisive issues out of the way. The American institutional structure had been able to cope with sectional problems and disagreements; before the 1850s, after all, the nation had already seen sectional disputes centered on the issue of slavery in the West. These disputes did not lead to civil war, but rather the Missouri Compromise in 1820 and the Compromise of 1850.

However, as the Industrial Revolution was gaining momentum in the North, the pro-Southern Democratic party was increasingly seen as a barrier to progress in the areas of transportation, tariffs, schooling, and banking policy. Moreover, as modern capitalist development transformed the economy and society in the North, the corresponding rise of mass politics undermined the stability of the old two-party system. Sectional ideologies grew more and more vitriolic after 1856, and the growth of mass politics allowed these sentiments to enter politics with the help of the pamphlets, speeches, and newspaper articles by the Republican radicals. Sectional tensions – once merely an elite concern – were now increasingly tinged by mass ideologies of free-soil and free-labor. Even the Constitution was now emerging as a source of division; in 1857, the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford highlighted the ambiguity of the Constitution, undermining the unifying force that the nationalistic veneration of Constitution had provided.

Although indispensable mechanisms for regulating the balance of power between sectional interests in politics were being considerably eroded, revisionist historians, such as Randall and Craven, have argued that their repair would not have been out of the question had the nation been led by a more able generation of politicians. Most notably, the controversy over the Lecompton constitution, in 1858, offered the best opportunity for an alliance between the moderate-to-conservative wing of the Republican Party and anti-administration Southerners.

The Republicans and anti-administration Democrats

President Buchanan decided to end the troubles in Kansas by urging Congress to admit Kansas as a slave state under the Lecompton constitution. Kansas voters, however, soundly rejected this constitution— at least with a measure of widespread fraud on both sides— by more than 10,000 votes. As Buchanan directed his presidential authority to this goal, he further angered the Republicans and alienated members of his own party. Prompting their break with the administration, the Douglasites saw this scheme as an attempt to pervert the principle of popular sovereignty on which the Kansas-Nebraska Act was based. Nationwide, conservatives were incensed, feeling as though the principles of states' rights had been violated. Even in the South, ex-Whigs and border states Know-Nothings— most notably John Bell and John J. Crittenden (key figures in the event of sectional controversies)— urged the Republicans to oppose the administration's moves and take up the demand that the territories be given the power to accept or reject sovereignty.

As the schism in the Democratic party deepened, moderate Republicans argued that an alliance with anti-administration Democrats, especially Stephen Douglas, would be a key advantage in the 1860 elections. Some Republican observers saw the controversy over the Lecompton constitution as an opportunity to peel off Democratic support in the border states, where Frémont picked up little support. After all, the border states had often gone for Whigs with a Northern base of support in the past without prompting threats of Southern withdrawal from the Union.

Among the proponents of this strategy was the New York Times, which called on the Republicans to downplay opposition to popular sovereignty in favor of a compromise policy calling for "no more slave states" in order to quell sectional tensions. The Times maintained that for the Republicans to be competitive in the 1860 elections, they would need to broaden their base of support to include all voters who for one reason or another were upset with the Buchanan administration.

Indeed, pressure was strong for an alliance that would unite the growing opposition to the Democratic administration. But such an alliance was no novel idea; it would essentially entail transforming the Republicans into the national, conservative, Union party of the country. In effect, this would be a successor to the Whig party.

Republican leaders, however, staunchly opposed any attempts to modify the party position on slavery, appalled by what they considered a surrender of their principles when, for example, all the ninety-two Republican members of Congress voted for the Crittenden-Montgomery bill in 1858. Although this compromise measure blocked Kansas' entry into the union as a slave state, the fact that it called for popular sovereignty, rather than outright opposition to the expansion of slavery, was deeply troubling to the party leaders.

In the end, the Crittenden-Montgomery bill did not forge a grand anti-administration coalition of Republicans, ex-Whig Southerners in the border states, and Northern Democrats. Instead, the Democratic Party merely split along sectional lines. In a desperate move to reassert control over his party, Buchanan applied the patronage whip ruthlessly. Anti-Lecompton Democrats complained that a new, pro-slavery test had been imposed upon the party. The Douglasites, however, refused to yield to administration pressure. Like the anti-Nebraska Democrats, who were now members of the Republican Party, the Douglasites insisted that they— not the administration— commanded the support of most northern Democrats.

As the Southern planter class saw its stranglehold over the executive, legislative, and judicial apparatus of the central government wane, and as it grew increasingly difficult for Southern Democrats to manipulate power in many of the Northern states through their allies in the Democratic Party, extremist sentiment in the region hardened dramatically.

The internal structure and character of the Republican Party

Despite their significant loss in the election of 1856, Republican leaders realized that even though they appealed only to Northern voters, they need win only two more states, such as Pennsylvania and Illinois, to win the presidency in 1860.

As the Democrats were grappling with their own troubles, leaders in the Republican party fought to keep elected members focussed on the issue of slavery in the West, which allowed them to mobilize a great deal of popular support. Chase wrote Sumner that if the conservatives succeeded, it might be necessary to recreate the Free Soil party. He was also particularly disturbed by the tendency of many Republicans to eschew moral attacks on slavery for political and economic arguments.

As a caveat, it is important to note that the controversy over slavery in the West was still not creating a fixation on the issue of slavery. Although the old restraints on the sectional tensions were being eroded with the rapid extension of mass politics and mass democracy in the North, the perpetuation of conflict over the issue of slavery in the West still required the efforts of radical Democrats in the South and radical Republicans in the North. They had to ensure that the sectional conflict would remain at the center of the political debate.

William Seward, in fact, contemplated this potential as far back as the 1840s, when the Democrats were the nation's majority party, usually controlling Congress, the presidency, and many state offices. At the time, the country's institutional structure and party system allowed slaveholders to prevail in more and more of the nation's territories and to garner a great deal of influence over national policy. With growing popular discontent with the unwillingness of many Democratic leaders to take a stand against slavery, and growing consciousness of the party's increasingly pro-Southern stance, Seward became convinced that the only way for the Whig party to counteract the Democrats' strong monopoly of the rhetoric of democracy and equality was for the Whigs to embrace anti-slavery as a party platform. Once again, to increasing numbers of Northerners, the Southern labor system was increasingly seen as contrary to the ideals of American democracy.

Republicans believed in the existence of "the Slave Power Conspiracy," which had seized control of the federal government and was attempting to pervert the Constitution for its own purposes. The "Slave Power" idea gave the Republicans the anti-aristocratic appeal with which men like Seward had long wished to be associated politically. By fusing older anti-slavery arguments with the idea that slavery posed a threat to Northern free labor and democratic values, it enabled the Republicans to tap into the egalitarian outlook which lay at the heart of Northern society.

In this sense, during the 1860 Presidential campaign, Republican orators even cast "Honest Abe" as an embodiment of these principles, repeatedly referring to him as "the child of labor" and "son of the frontier," who had proved how "honest industry and toil" were rewarded in the North. Although Lincoln had been a Whig, the "Wide Awakes" (members of the Republican clubs), used replicas of rails that he had split to remind voters of his humble origins.

In almost every northern state, organizers attempted to have a Republican party or an anti-Nebraska fusion movement on ballots in 1854. In areas where the radical Republicans controlled the new organization, the comprehensive radical program became the party policy. Just as they helped organize the Republican Party in the summer of 1854, the radicals played an important role in the national organization of the party in 1856. Republican conventions in New York, Massachusetts, Illinois adopted radical platforms. These radical platforms in such states as Wisconsin, Michigan, Maine, and Vermont usually called for the divorce of the government from slavery, the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Laws, and no more slave states, as did platforms in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Massachusetts when radical influence was high.

Conservatives at the Republican 1860 nominating convention in Chicago were able to block the nomination of William Seward, who had an earlier reputation as a radical (but by 1860 had been criticized by Horace Greeley as being too moderate). Other candidates had earlier joined or formed parties opposing the Whigs and had thereby made enemies of many delegates. Lincoln was selected on the third ballot. However, conservatives were unable to bring about the resurrection of "Whiggery." The convention's resolutions regarding slavery were roughly the same as they had been in 1856, but the language appeared less radical. In the following months, even Republican conservatives like Thomas Ewing and Edward Baker embraced the platform language that "the normal condition of territories was freedom". All in all, the organizers had done an effective job of shaping the official policy of the Republican Party.

Southern slaveholding interests now faced the prospects of a Republican president and the entry of new free states that would alter the nation's balance of power between the sections. To many Southerners, the resounding defeat of the Lecompton constitution foreshadowed the entry of more free states into the Union. Dating back to the Missouri Compromise, the Southern region desperately sought to maintain an equal balance of slave states and free states so as to be competitive in the Senate. Since the last slave state was admitted in 1845, five more free states had entered. The likelihood of continuing the tradition of balance was growing more and more unlikely.

Sectional battles over federal policy in the late 1850s

Background

Dating back to the conflicts pitting Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson against each other, there had been a tug-of-war between agrarians and urban and financial interests over banking, trade, land grants, and internal improvements. Not until the 1920s, however, had the idea of the war as an irrepressible economic conflict, rather than a moral conflict, received full expression in the historical literature on the subject.

In The Rise of American Civilization (1927), Charles and Mary Beard argue that slavery was not so much a social or cultural institution as an economic one (i.e. a labor system). The Beards, along with Louis Hacker in his The Triumph of American Capitalism: The Development of Forces in American History to the End of the Nineteenth Century (1940), cite inherent conflicts between Northeastern finance, manufacturing, and commerce and Southern plantations, which competed to control the federal government so as to protect their own interests. According to the economic determinists of the era, both groups used arguments over slavery and states' rights as a cover.

Recent historians do not accept the so-called Beard-Hacker thesis wholeheartedly. But their economic determinism has influenced subsequent historians in important ways. Modernization theorists, such as Raimondo Luraghi, have argued that as the Industrial Revolution was expanding on a worldwide scale, the days of wrath were coming for a series of agrarian, pre-capitalistic, "backward" societies throughout the world, from the Italian and American South to India. Luraghi relates the expansion of capitalism on a world scale to the emergence of an anti-slavery movement in the United States, placing the Civil War in the context of the general abolition of unfree labor systems in the nineteenth century, from slavery in the Western hemisphere, to serfdom in Russia and robot in the Austro-Hungarian empire

Barrington Moore, in Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (1966), however, disagrees, arguing that whether there was conflict or compromise depended on the set of historical conditions at a certain time. Using a comparative historical framework, Moore stresses how landed aristocracies were able to maintain their political and economic power into the modern era in certain societies. In this regard, the German historical record is suggestive. The political and economic links were there for an agreement between the German landed aristocracy and the nation's rising bourgeois classes. Unlike the Southern planter class, the Prussian Junkers, under the tutelage of Reichskanzler Otto von Bismarck, managed to draw the independent farmers under their influence and to form an alliance with sections of big industry that were happy to receive their assistance in order to keep the trade unions and the socialists (see Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands) in their place with a combination of repression and paternalism. Special historical circumstances, thus, had to be present in order to prevent agreement between an agrarian society based on unfree labor and a rising industrial capitalism. Unlike in Germany, Northern capitalists— at least comparatively— were able to align with other groups in American society.

The Panic of 1857 and sectional realignments

Specifically, the serious financial panic of 1857, and economic difficulties leading up to it, strengthened the Republican Party and sectional tensions. Before the panic, strong economic growth was being achieved under relatively low tariffs. Hence much of the nation concentrated on growth and prosperity. For example, for the few years after the Compromise of 1850, sectional conflict abated until the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Against this backdrop, however, the iron and textile industries were facing acute, worsening trouble each year after 1850. By 1854, stocks of iron were accumulating in each world market. Iron prices fell, forcing many American iron mills to shut down. Soon afterwards, Western farmers emerged as another distressed group. The Crimean War had propped up demand for American exports of food, but when the conflict ended in 1856, demand for food fell, resulting in a steep decline in prices.

Western farmers and Northern manufacturers would come to blame the depression on the domination of the low-tariff economic policies of Southern-controlled Democratic administrations. But at least when the panic started, the depression revived latent, deep-seated suspicion of Northeastern banking and trading interests not only in just the South, but also in the West. As a result of spiraling interest payments to lenders, many settlers in the West who lost their land through foreclosures cursed "Boston plutocrats" and "New York Shylocks." In the South, where the impact of the panic was relatively slight, commercial centers in the North were the objects of similar derision. Some Southern commentators even regarded the plight of Northern manufacturers as evidence of the superiority of Southern economic institutions.

Instead, a deepening chasm would arise between slave states and free states. Eastern demand for Western farm products changed this situation, shifting the West closer to the North. As the "transportation revolution" (canals and railroads) and advancements in communication (especially telegraphs) went forward, an increasingly large share and absolute amount of wheat, corn, and other staples of Western producers went to markets in the Northeast— once difficult to haul across the Appalachians.

However, the high cost of transportation caused wheat bought for $.70 in the West to be sold at a price of $1.20 in New York. In this context, the depression raised demands in the West for federal subsidies and internal improvements in transportation (e.g., roads, canals, and harbor facilities). Improvements in transportation would drive down prices of wheat transported by rail to the East. Above all, the depression suggested to industrialists and traders that nothing was more important than the rapid development of Western markets for Eastern goods— and homesteaders who would furnish markets and respectable profits.

The panic calmed the fear of Northern manufacturers of future labor shortages resulting from westward migration, thus bolstering the case made by advocates of free land— and hostile Southern reactions to these prospects. Meanwhile, the free soil press and the Republican Party encouraged a strong popular reaction. Noting that Southern plantation interests in the Senate had killed the Homestead Bill of 1852, free soil newspapers in the West often promulgated the dubious claim that had it not been for the defeat of the Homestead Bill, the price of land sold by the government would have been lower, and that somehow this would have prevented the depression.

The existence of free land in the United States united workers and capitalists in the United States. Not threatened by the revolutionary sentiments of an urban proletariat and uprising peasantry, industrial and agrarian elites lacked the incentives to unite as in Germany or Italy. Instead, the connection between Northern capitalism and Western farming meant it was unnecessary for the elites of North and South to unite in common interest--a union which could have averted the war.

As a point of comparison, less than a decade earlier, unemployed workers across the Atlantic, with the emphatic cry of "bread or lead!" hoisted the red flag— the first time that the red flag emerged as a symbol of the proletariat— and erected barricades to overthrow the French Second Republic.

Although bread lines and soup kitchens emerged in the North after the panic of 1857, U.S. cities were not teeming with unemployed artisans and sans-culottes; nor were there European-style peasant wars. While Europe was seeing the rise of radical movements, trade unions, and revolutionary programs, the United States saw schemes designed to provide free farms to needy Eastern workers after 1857. In sum, the American frontier strengthened the forces of early competitive and individualist capitalism by spreading the interest in property ownership.

Aside from the land issue, economic difficulties strengthened the Republican case for higher tariffs for industries in response to the depression. Republican proclamations that the backward, agrarian, and feudalistic South dominated the national government, of course, played well with many constituencies across the North. It was during the Democratic Polk administration, after all, that Southern votes had been chiefly responsible for the low Walker tariff of 1846.

The Southern response

Meanwhile, many Southerners grumbled over "radical" notions of giving land away to farmers that would "abolitionize" the area. While the ideology of Southern sectionalism was well-developed before the Panic of 1857 by figures like J.D.B DeBow, the panic helped convince even more cotton barons that they had grown too reliant on Eastern financial interests. Thomas Prentice Kettell, former editor of the Democratic Review, was another commentator popular in the South to enjoy a great degree of prominence between 1857 and 1860. Kettell gathered an array of statistics in his book on Southern Wealth and Northern Profits, to show that the South produced vast wealth, while the North, with its dependence on raw materials, siphoned off up the wealth of the South.[5] Arguing that sectional inequality resulted from the concentration of manufacturing in the North, and from the North's supremacy in communications, transportation, finance, and international trade, his ideas paralleled old physiocratic doctrines that all profits of manufacturing and trade come out of the land.[6] Political sociologists, such as Barrington Moore, have noted that these forms of romantic nostalgia tend to crop up whenever industrialization takes hold.[7]

Such Southern hostility to the free farmers gave the North an opportunity for an alliance with Western farmers. After the political realignments of 1857-1858, manifested by the emerging strength of the Republican Party and their networks of local support nationwide, almost every issue would now become entangled with the controversy over the expansion of slavery in the West. While questions of tariffs, banking policy, public land, and subsidies to railroads did not always unite all elements in the North and the Northwest against the interests of slaveholders in the South under the pre-1854 party system, they would now get translated in terms of sectional conflict—with the expansion of slavery in the West involved.

As the depression strengthened the Republican Party, slaveholding interests were becoming convinced that the North had aggressive and hostile designs on the Southern way of life. The South was thus increasingly fertile ground for secessionist extremism.

While the Republicans' Whig-style personality-driven "hurrah" campaign certainly helped whip up hysteria in the slave states upon the emergence of Lincoln and intensify divisive tendencies, Southern "fire eaters" certainly gave credence to notions of the slave power conspiracy among Republican constituencies in the North and West. And new Southern demands to re-open the African slave trade certainly did not help to assuage sectional tensions.

From the early 1840s, until the outbreak of the Civil War, the cost of slaves had been rising steadily. Meanwhile, the price of cotton was experiencing marked fluctuations (typical of raw commodities). After the Panic of 1857, the price of cotton fell, while the price of slaves had continued its steep rise. At the next year's Southern commercial convention, William L. Yancey of Alabama called for the reopening of the African slave trade. Only the delegates from the states of the Upper South, who profited from the domestic trade, opposed the reopening of the slave trade — a potential form of competition to them. The convention in 1858 wound up voting to recommend the repeal of all laws against slave imports, despite some reservations

The emergence of Lincoln

Elections of 1860

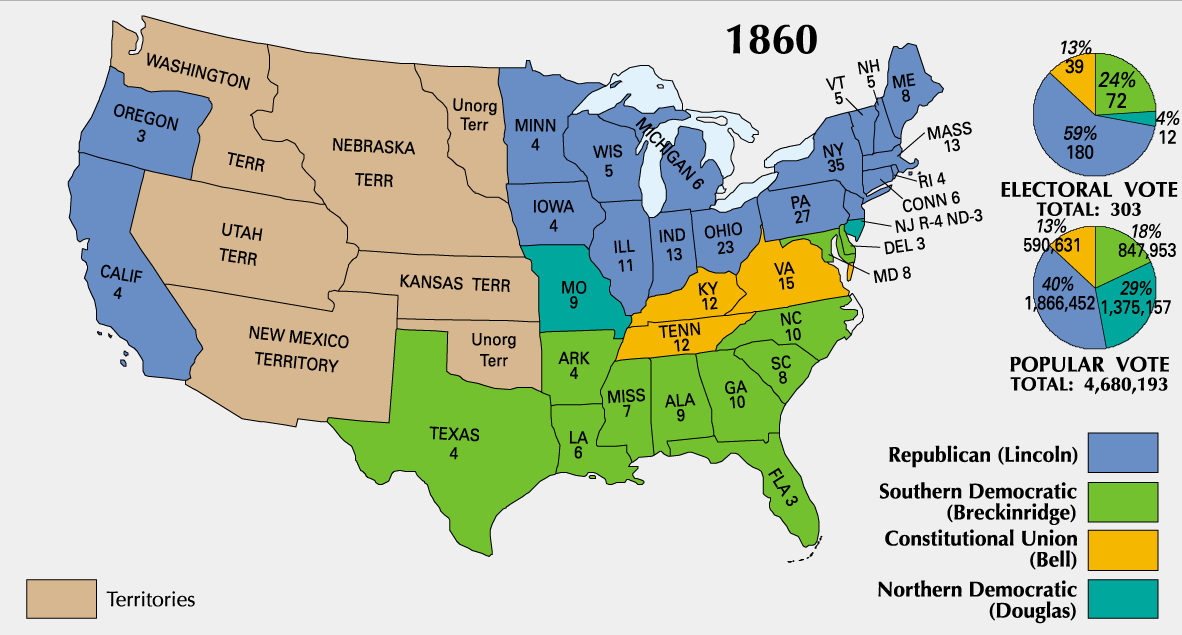

Initially, William H. Seward of New York, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania were the leading contenders for the Republican presidential nomination. But Abraham Lincoln, a former one-term House member who gained fame amid the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 had fewer political opponents within the party and out-maneuvered the other contenders. On May 16, he received the Republican nomination at their convention in Chicago, Illinois.

The schism in the Democratic Party over the Lecompton constitution caused Southern "fire-eaters" to oppose frontrunner Stephen A. Douglas' bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. Southerners left the party and, in June, nominated John C. Breckinridge, while Northern Democrats supported Douglas. As a result, the Southern planter class lost a considerable measure of sway in national politics. Because of the Democrats' division, the Republican nominee would face a divided opposition.

Adding to Lincoln's advantage, ex-Whigs from the border states had earlier formed the Constitutional Union Party, nominating John C. Bell for president. Thus, party nominees waged regional campaigns. Douglas and Lincoln competed for Northern votes, while Bell, Douglas and Breckinridge competed for Southern votes.

"Vote yourself a farm— vote yourself a tariff" could have been a slogan for the Republicans in 1860. In sum, business was to support the farmers' demands for land (popular also in industrial working-class circles) in return for support for a higher tariff. The Civil War has been called a "second American revolution." To an extent, after all, the elections of 1860 bolstered the political power of new social forces unleashed by the Industrial Revolution. In February 1861, after the seven states had departed the Union (four more would depart in April-May 1861; in late April, Maryland was unable to secede because it was put under martial law) , Congress had a strong northern majority and passed and Buchanan signed the Morrill Tariff Act, which increased duties and provided the government with funds needed for the war.

Southern secession

With the emergence of the Republicans as the nation's first major sectional party by the mid-1850s, politics became the stage on which sectional tensions were played out. Although much of the West— the focal point of sectional tensions— was unfit for cotton cultivation, Southern secessionists read the political fallout as a sign that their power in national politics was rapidly weakening. Before, the slave system had been buttressed to an extent by the Democratic Party, which was increasingly seen as representing a more pro-Southern position that unfairly permitted Southerners to prevail in more and more of the nation's territories and to dominate national policy before the Civil War. But they suffered a significant reverse in the electoral realignment of the mid-1850s. 1860 was a critical election that marked a stark change in existing patterns of party loyalties among groups of voters; Abraham Lincoln's election was a watershed in the balance of power of competing national and parochial interests and affiliations.

Once the election returns were certain, a special South Carolina convention declared "that the Union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states under the name of the 'United States of America' is hereby dissolved," heralding the secession of ten more Southern states by May 21, 1861. With Southern opposition removed in Congress, the Republicans did not attempt to satisfy Southern demands in a way that could have produced a compromise.

The onset of the Civil War and the question of compromise

The question of compromise (especially Abraham Lincoln's rejection of the Crittenden Compromise and the failure to secure the ratification of the Corwin amendment in 1861) opens up one of the enduring debates in Civil War historiography. Even as the war was going on, William Seward and James Buchanan were outlining a debate over the question of inevitability that would continue among historians for more than a century to come.

Two competing explanations of the sectional tensions inflaming the nation emerged even before the war. Buchanan believed the sectional hostility to be the accidental, unnecessary work of self-interested or fanatical agitators. He also singled out the "fanaticism" of the Republican Party. Seward, on the other hand, believed there to be an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces.

The irrepressible conflict argument was the first to dominate historical discussion. In the first decades after the fighting, histories of the Civil War generally reflected the views of Northerners who had participated in the conflict. The war appeared to be a stark moral conflict in which the South was to blame, a conflict that arose as a result of the designs of slave power. Henry Wilson's History of the Rise and Fall of Slave Power (1872-1877) is the foremost representative of this moral interpretation, which argued that Northerners had fought to preserve the union against the aggressive designs of "slave power." Later, in his seven-volume History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Civil War, (1893-1900), James Ford Rhodes identified slavery as the central, and virtually only, cause of the Civil War. The North and South had reached positions on the issue of slavery that were both irreconcilable and unalterable. The conflict had become inevitable.

But the idea of the war as avoidable did not gain ground among historians until the 1920s, when the "revisionists" began to offer new accounts of the prologue to the conflict. Revisionist historians, such as James G. Randall and Avery Craven saw in the social and economic systems of the South no differences so fundamental as to require a war. Randall blamed the ineptitude of a "blundering generation" of leaders. He also saw slavery as essentially a benign institution, crumbling in the presence of nineteenth century tendencies. Craven, the other leading revisionist, placed more emphasis on the issue of slavery than Randall, but argued roughly the same points. In The Coming of the Civil War (1942), Craven argued that slave laborers were not much worse off than Northern workers, that the institution was already on the road to ultimate extinction, and that the war could have been averted by skillful and responsible leaders in the tradition of the great Congressional statesmen Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Two of the most important figures in US politics in the first half of the 19th century, Clay and Webster, arguably in contrast to the 1850s generation of leaders, shared a predisposition to compromises marked by a passionate patriotic devotion to the Union.

But it is still possible that the politicians of the 1850s were not unusually inept after all. More recent studies have kept elements of the revisionist interpretation alive, emphasizing the role of political agitation (i.e. the efforts of Democratic politicians of the South and Republican politicians in the North to keep the sectional conflict at the center of the political debate). The leading historian in the field until his death, David Herbert Donald argued in 1960 that the politicians of the 1850s were not unusually inept but that they were operating in a society in which traditional restraints were being eroded in the face of the rapid extension of democracy. In short, the stability of the two-party system kept the union together, but would collapse in the 1850s, thus reinforcing, rather than suppressing, sectional conflict.

Reinforcing this interpretation, political sociologists have pointed out that the stable functioning of a political democracy requires a setting in which parties represent broad coalitions of varying interests, and that peaceful resolution of social conflicts takes place most easily when the major parties share fundamental values. Before the 1850s, the second American two party system (i.e. competition between the Democrats and the Whigs) conformed to this pattern, largely because sectional ideologies and issues were kept out of politics to maintain cross-regional networks of political alliances. However, in the 1840s and 1850s ideology made its way into the heart of the political system, despite the best efforts of the conservative Whig Party and the Democratic Party to keep it out.

References

- ^ Freehling, William V. (1966). Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina., is a narrative account of the crisis. A broader study is Syndor, Charles S. (1948). The Development of Southern Sectionalism 1819-1848.. Peterson, Merrill D. (1983). Olive Branch and the Sword: The Compromise of 1833., examines the resolution of the crisis.

- ^ North, Douglas C. (1961). The Economic Growth of the United States 1790-1860. Englewood Cliffs. p. 130.

- ^ Moore, Barrington (1966). Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York: Beacon Press. p. 117.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (1986). American History: A Survey. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 328.

- ^ Donald, David (1961). The Civil War and Reconstruction. Boston: D.C. Health and Company. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Allan, Nevins (1947). Ordeal of the Union (vol. 3). Vol. III. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 218.

- ^ Moore, Barrington. p. 122.

Secondary Sources

Historiography

- Beale, Howard K., "What Historians Have Said About the Causes of the Civil War," Social Science Research Bulletin 54, 1946.

- Boritt, Gabor S. ed. Why the Civil War Came (1996)