Masculinity: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Irrelevant information. |

Re- added link to Heavy Metal. Ms. Blake, I do not mean to imply that only certain people can participate in metal, but only to add a reference to the undeniably masculine atmosphere, lyrical themes, and culture of the genre. |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

*[[Raewyn Connell]] |

*[[Raewyn Connell]] |

||

*[[Emasculation]] |

*[[Emasculation]] |

||

*[[Heavy Metal Music]] |

|||

=== Books === |

=== Books === |

||

Revision as of 20:20, 2 August 2012

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Masculinity is possessing qualities or characteristics considered typical of or appropriate to a man. The term can be used to describe any human, animal or object that has the quality of being masculine. When masculine is used to describe men, it can have degrees of comparison—more masculine, most masculine. The opposite can be expressed by terms such as unmanly or epicene.[1] A typical near-synonym of masculinity is virility (from Latin vir, man).

Constructs of masculinity vary across historical and cultural contexts. The dandy, for instance, was regarded as an ideal of masculinity in the 19th century, but is considered "effeminate" by modern standards.[2]

Origins

The extent to which masculinity is due to socialization versus inborn factors has been the subject of much debate. Some have argued that it is based largely on biology as masculinity is inextricably linked with the male body. In this view, masculinity is something that is associated with the biological male sex and having male genitalia, for instance, is regarded as a natural aspect of masculinity.[4] Others have suggested that while masculinity may be influenced by biological factors, it is also culturally constructed. As such, masculinity is not restricted to men and can, in fact, be female as women frequently display behavior, traits and physical attributes that are considered "masculine" in a given historical and social context.[4] Proponents of this view point out that women can become men hormonally and physically[5] and that many aspects that are assumed to be natural are linguistically and therefore culturally driven. Facial hair, for instance, has been linked to masculinity through language in such forms as stories about boys becoming men when they start to shave.[6]

Masculinity does not have a single source of origin or creator such as the media, certain institutions, or certain groups of people. While the military, for example, has a vested interest in constructing and promoting a specific form of masculinity, it does not create it from scratch and masculinity has influenced the creation of the military in the first place.[7]

History

Ancient

"a man's chief quality is courage." - Cicero

"Viri autem propria maxime est fortitudo." Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1:11:18.</ref>

Ancient literature goes back to about 3000 BC. It includes both explicit statements of what was expected of men in laws, and implicit suggestions about masculinity in myths involving gods and heroes. In 1000 BCE, The Hebrew Bible states King David of Israel told his son "Be strong, and be a man" upon David's death. Men throughout history have gone to meet exacting cultural standards of what is considered attractive. Kate Cooper, writing about ancient understandings of femininity, suggests that, "Wherever a woman is mentioned a man's character is being judged – and along with it what he stands for."[8] One well-known representative of this literature is the Code of Hammurabi (from about 1750 BC).

- Rule 3: "If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death."

- Rule 128: "If a man takes a woman to wife, but has no intercourse with her, this woman is no wife to him."[9]

Scholars suggest integrity and equality as masculine values in male-male relationships,[10] and virility in male-female relationships. Legends of ancient heroes include: The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Such narratives are considered to reveal qualities in the hero that inspired respect, like wisdom or courage, the knowing of things that other men do not know and the taking of risks that other men would not dare.

Medieval

Jeffrey Richards describes a European, "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric."[11] Again ethics, courage and generosity are seen as characteristic of the portrayal of men (=niela) in literary history. Anglo Saxon Beowulf, Hengest and Horsa are famous examples of medieval ideals of masculinity.

Multiple masculinities

Masculinity is not a conscious process; it is perpetuated through social institutions and is enforced and policed through individual interactions. R.W. Connell introduced the idea of multiple masculinities rather than a single category that every man fits into. She recognizes that there are intersections and variations of masculinity based on race, location, culture, time period, age, ability, etc. and developed four classifications: hegemony, subordination, complicity, and marginalization.

Hegemonic masculinity is the norm, something that men are expected to aspire to and that women are discouraged from associating with. “Hegemonic masculinity can be defined as the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees the dominant position of men and the subordination of women.” (Connell, 2001) The military, top levels of businesses, and government agencies provide leading examples of this facet of masculinity within society. It is an expectation of what a “real man” should act and look like, but in reality no one can successfully achieve hegemony.

Connell's idea of hegemonic masculinity is not only seen in men but it is clear among young children in school as well. This concept invokes a leading way of doing gender relations that implements the gender order status quo by raising the general status of masculine qualities over feminine qualities. The idea of hegemonic masculinity in the context of young boys is used to re-create gender order in childhood play where the general ideas of men's dominance are learned and reinforced.[citation needed]

Subordinate masculinity is the cultural authority of heterosexual men and subordination of homosexual men. “Gayness” is viewed as the polar opposite of what masculinity entitles a man to be; therefore it is associated with femininity and is politically, economically, and culturally attacked. Heterosexual men view gay men in the same light that they view women[citation needed], meaning that there is an innate need for dominance. This leads to the subordination of men who present their masculinity in the “wrong” way and are seen as having a failed hegemonic masculinity.[citation needed]

Complicit masculinity is the categorization of men who connect with hegemony but do not fully represent hegemonic masculinity. “A great many men who draw the patriarchal dividend also respect their wives and mothers, are never violent towards women, do their accustomed share of the housework, bring home the family wage, and can easily convince themselves that feminists must be bra-burning extremists.” (Connell, 2001) Men that fall into this category do not receive the same benefits and privileges as those who are seen as purely hegemonic.

Marginalized masculinity is the authorization of the hegemonic masculinity. Men who fall into this category benefit less from the hegemonic ideal because of traits other than their gender behavior. “Race relations may also become integral part of the dynamic between masculinities. In a white-supremacist context, black masculinities play symbolic roles for white gender construction.” (Connell, 2001) In other words, the hegemonic masculinity among whites maintains the oppression against the masculinity among blacks.

Though these concepts have been discussed in context to men, masculinity affects everyone. Both men and women can benefit from or be oppressed by the expectations of masculinity that are meant to be lived up to in society.[citation needed]

Masculine physical attributes

Some researchers argue that a large number[clarification needed] of women are aroused mostly by broad chins and shoulders and high cheekbones, though there are cultural differences in those preferences, and arousal may be an indication of socialized notions of attractiveness. Other research suggests that women unconsciously recognize a sculpted physique as indicative of "masculine" discipline, focus and self-control.[citation needed]

Biology and culture

Some gender studies scholars will use the phrase "hegemonic masculinity" to refer to an ideal of male behavior which men are strongly encouraged to aim for, which is calculated to guarantee the dominant position of some men over others.

Western trends

According to a paper submitted by Tracy Tylka to the American Psychological Association (APA), in contemporary America: "Instead of seeing a decrease in objectification of women in society, there has just been an increase in the objectification of both sexes. And you can see that in the media today." Men and women restrict their food intake in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively thin body, in extreme cases leading to eating disorders.[12] Thomas Holbrook, also a psychiatrist, cites a recent Canadian study indicating as many as one in six of those with eating disorders were men.[13]

"Younger men and women who read fitness and fashion magazines could be psychologically harmed by the images of perfect female and male physiques," according to recent research in the United Kingdom. Some young women and men exercise excessively in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively fit and muscular body, which in extreme cases can lead to body dysmorphic disorder or muscle dysmorphia.[14][15][16]

Although the actual stereotypes may have remained relatively constant, the value attached to the masculine and feminine stereotypes have changed over the past few decades.

Those associated with recent work in the study of masculinity from a philosophical perspective view masculinity as an unstable phenomenon and never ultimately achieved.[17]

Notion of "masculinity in crisis"

A mounting discourse of "masculinity in crisis" has emerged recently from newspapers and books arguing that masculinity is in a state of crisis.[18] For instance, Australian archeologist Peter McAllister stated, "I have a strong feeling that masculinity is in crisis. Men are really searching for a role in modern society; the things we used to do aren't in much demand anymore".[19] Others see the changing labor market as a source of the alleged crisis. Deindustrialization and the replacement of old smokestack industries with new technologies has allowed more women to enter the labor force and reduced the demand for great physical strength.[20] The supposed crisis has also been frequently attributed to feminism. Men's dominance over women and the "rights" which were granted to men solely on the basis of their sex have been called into question.[21] British sociologist John MacInnes argued that "masculinity has always been in one crisis or another" and suggested that the crises arise from the "fundamental incompatibility between the core principle of modernity that all human being are essentially equal (regardless of their sex) and the core tenet of patriarchy that men are naturally superior to women and thus destined to rule over them."[22]

Academic John Beynon examined the discourse surrounding the notion of masculinity in crisis and found that masculinity and men are often confused and conflated so that it remains unclear whether masculinity, men, or both are supposed to be in crisis.[23] He further argues that the alleged crisis is not a recent phenomenon and points out several periods of masculine crisis throughout history, many of which predate the women's movement and post-industrial societies. He suggests that due to the fact that masculinity is always changing and redefined, "crisis is constitutive of masculinity itself."[24] Film scholar Leon Hunt contends in the same vein, "Whenever masculinity's 'crisis' actually started, it certainly seems to have been in place by the 1970s".[25]

Development

This section possibly contains original research. (December 2007) |

A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics and the process of sexual differentiation specific to the reproductive system of Homo sapiens. The SRY gene on the Y chromosome interferes with the process of creating a female, causing a chain of events that leads to testes formation, androgen production, and a range of both natal and post-natal hormonal effects. There is an extensive debate about how children develop gender identities.

In many cultures, displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Within sociology such labeling and conditioning is known as gender assumptions, and is a part of socialization to better match a culture's mores. Among men, some non-standard behaviors may be considered a sign of homosexuality, which frequently runs contrary to cultural notions of masculinity. When sexuality is defined in terms of object choice, as in early sexology studies, male homosexuality is interpreted as "feminine" sexuality. The corresponding social condemnation of excessive masculinity may be expressed in terms such as machismo or testosterone poisoning.

The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While social conditioning obviously plays a role, some[who?] hold that certain aspects of the feminine and masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures, though this has not been thoroughly substantiated[citation needed].

The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as behavioral genetics, evolutionary psychology, human ecology, anthropology and sociology. All human cultures seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through literature, costume and song. Some examples of this might include the epics of Homer, Hengest and Horsa tales in English, the normative commentaries of Confucius. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the Bhagavad Gita or bushidō's Hagakure.

Another term for a masculine woman is butch, which is associated with lesbianism. Butch is also used within the lesbian community, without a negative connotation, but with a more specific meaning (Davis and Lapovsky Kennedy, 1989).

Downside and failure of concept

It is a subject of debate whether masculinity concepts followed historically should still be applied. Researchers such as Care International have argued that there is a harmful downside due to considerations such as the following:

- The relationship between masculinity and gender-based violence[26]

- The disempowerment and impoverishment of women and the persistence of gender inequalities through men’s violence[26]

- The loss of men's dignity and self-esteem when they are taught to behave violently

The images of boys and young men presented in the media may lead to the persistence of harmful concepts of masculinity. Men's rights activists argue that the media does not pay serious attention to men's rights issues and that men are often portrayed in a negative light, particularly in advertising.[27]

Pressures associated

In 1987, Eisler and Skidmore did studies on masculinity and created the idea of 'masculine stress'. They found four mechanisms of masculinity that accompany masculine gender role often result in emotional stress. They include:

- The emphasis on prevailing in situations requiring body and fitness

- Being perceived as emotional

- The need to feel adequate in regard to sexual matters and financial status

Because of social norms and pressures associated with masculinity, Men with spinal cord injuries have to adapt their self identity to the losses associated with SCI which may “lead to feelings of decreased physical and sexual prowess with lowered self-esteem and a loss of male identity. Feelings of guilt and overall loss of control are also experienced.”[28]

Masculinity is something that some fear is becoming increasingly challenged, especially in the last century, with the emergence of Women's rights and the development of the role of women in society. In recent years many 'Man Laws' and similar masculinist manifestos have been published, as a way for men to re-affirm their masculinity. A popular example is the Miller Lite Man Laws, and other various sites on the internet offering rules such as: "15. A real man does not need instruction manuals." [29] Although many of these rules are offered in a humorous fashion, they attempt to define masculinity, and indicate that proper gender is taught and performed rather than intuited.

Research also suggests that men feel social pressure to endorse traditional masculine male models in advertising. Research by Martin and Gnoth (2009) found that feminine men preferred feminine models in private, but stated a preference for the traditional masculine models when their collective self was salient. In other words, when concerned about being classified by other men as feminine, feminine men endorsed traditional masculine models. The authors suggested this result reflected the social pressure on men to endorse traditional masculine norms [30]

Risk-taking

The driver crash rate per vehicle miles driven is higher for women than for men; although, men are much more likely to cause deaths in the accidents they are involved in.[31] Men drive significantly more miles than women, so, on average, they are more likely to be involved in motor vehicle accidents. Even in the narrow category of young (16-20) driver fatalities with a high blood alcohol content (BAC), a male's risk of dying is higher than a female's risk at the Same BAC level.[32] That is, young women drivers need to be more drunk to have the same risk of dying in a fatal accident as young men drivers.

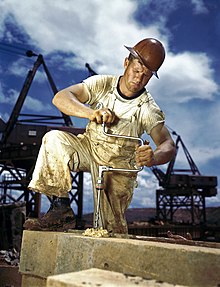

Men are three times more likely to die in all kinds of accidents than women. In the United States, men make up 92% of workplace deaths, indicating either a greater willingness to perform dangerous work, a societal expectation to perform this work, or that women are not hired for this work.[33]

Health care

A growing body of evidence is pointing toward the deleterious impact of masculinity (and hegemonic masculinity in particular) on men's health help-seeking behaviour.[34] American men make 134.5 million fewer physician visits than American women each year. In fact, men make only 40.8% of all physician visits, that is, if women's visits for pregnancy are included, childbirth and associated obstetrical and gynecological visits. A quarter of the men who are 45 to 60 do not have a personal physician. Many men should go to annual heart checkups with physicians but do not, increasing their risk of death from heart disease. Men between the ages of 25 and 65 are four times more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than women. Men are more likely to be diagnosed in a later stage of a terminal illness because of their reluctance to go to the doctor.

Reasons men give for not having annual physicals and not visiting their physician include fear, denial, embarrassment, a dislike of situations out of their control, or not worth the time or cost.

Media encouragement

According to Arran Stibbe (2004), men's health problems and behaviors can be linked to the socialized gender role of men in our culture. In exploring magazines, he found that they promote traditional masculinity and claims that, among other things, men's magazines tend to celebrate "male" activities and behavior such as admiring guns, fast cars, sexually libertine women, and reading or viewing pornography regularly. In men's magazines, several "ideal" images of men are promoted, and that these images may even entail certain health risks.

Alcohol consumption behavior

Research on beer commercials by Strate (Postman, Nystrom, Strate, And Weingartner 1987; Strate 1989, 1990) and by Wenner (1991) show some results relevant to studies of masculinity. In beer commercials, the ideas of masculinity (especially risk-taking) are presented and encouraged. The commercials often focus on situations where a man is overcoming an obstacle in a group. The men will either be working hard or playing hard. For instance the commercial will show men who do physical labor such as construction workers, or farm work, or men who are cowboys. Beer commercials that involve playing hard have a central theme of mastery (over nature or over each other), risk, and adventure. For instance, the men will be outdoors fishing, camping, playing sports, or hanging out in bars. There is usually an element of danger as well as a focus on movement and speed. This appeals to and emphasizes the idea that real men overcome danger and enjoy speed (i.e. fast cars/driving fast). The bar serves as a setting for the measurement of masculinity (skills like pool, strength and drinking ability) and serves as a center for male socializing.

Traditional masculinity

Traditional avenues for men to gain honor were that of providing adequately for their families and exercising leadership.[35] The traditional family structure consisted of the father as the bread-winner and the mother as the homemaker. During World War II, women entered the workforce in droves to replace the soldiers who were sent overseas. While some returned home to resume their positions as homemakers if their husbands survived the war, others remained in the workplace. Over the decades since, women have risen to high political and corporate positions. This shift has caused an increase in women becoming the primary income-earners and men the primary care-givers[35]—a process author Jeremy Adam Smith calls "the daddy shift" in his 2009 book of that title.[36] As of 2007, 159,000 dads were primary care-givers and this number is increasing.[37] Dubbed stay-at-home dads, these men are performing duties in the home which are not being done by women. Regardless of age or nationality, men more frequently rank good health, harmonious family life and good relationships with their spouse or partner as important to their quality of life.[38]

See also

- Philandry

- Model of masculinity under fascist Italy

- Victorian masculinity

- Hypermasculinity

- Masculism

- Men's spaces

- International Men's Day

- Male bonding

- Masculine psychology

- Raewyn Connell

- Emasculation

- Heavy Metal Music

Books

- Manliness (book) (2006)

References

- Notes

- ^ Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus, 3rd. ed., Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

- ^ Reeser 2010, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Reeser 2010, p. 11.

- ^ a b Reeser 2010, pp. 3, 11–13.

- ^ Reeser 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Reeser 2010, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Reeser 2010, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Kate Cooper, The Virgin and The Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 19.

- ^ The Code of Hammurabi, translated by LW King, 1910.

- ^ Karen Bassi, ['Acting like Men: Gender, Drama, and Nostalgia in Ancient Greece', Classical Philology 96 (2001): 86-92.]

- ^ Richards Jeffrey (1999). "From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of 'Medieval' Masculinity". Cultural Values. 3: 213–234.

- ^ Pressure To Be More Muscular May Lead Men To Unhealthy Behaviors

- ^ Goode, Erica (2000-06-25). "Thinner: The Male Battle With Anorexia". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Magazines 'harm male body image'". BBC News. 2008-03-28. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Muscle dysmorphia – AskMen.com

- ^ Men Muscle in on Body Image Problems | LiveScience

- ^ Reeser, T. Masculinities in Theory, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- ^ Beynon 2002, pp. 75–97.

- ^ Rogers, Thomas (November 14, 2010). "The dramatic decline of the modern man". Salon. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ Beynon 2002, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Beynon 2002, pp. 83–86.

- ^ MacInnes, John (1998). The end of masculinity: the confusion of sexual genesis and sexual difference in modern society. Philadelphia: Open University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-335-19659-3.

- ^ Beynon 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Beynon 2002, pp. 89–93.

- ^ Hunt, Leon (1998). British low culture: from safari suits to sexploitation. London, New York: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-415-15182-5.

- ^ a b UNIFEM GENDER FACT SHEET No.5

- ^ Farrell, W. & Sterba, J. P. (2008) Does Feminism Discriminate Against Men: A Debate (Point and Counterpoint), New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hutchinson, Susan L "Heroic masculinity following spinal cord injury: Implications for therapeutic recreation practice and research". Therapeutic Recreation Journal. FindArticles.com. 07 Apr, 2009

- ^ "List of Man Law Rules/Rules for Men". Fucking Manly. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ Martin, Brett A. S. and Juergen Gnoth (2009), "Is the Marlboro Man the Only Alternative? The Role of Gender Identity and Self-Construal Salience in Evaluations of Male Models", Marketing Letters, 20, 353–367.

- ^ Johns Hopkins School Of Public Health (1998, June 18). Women Not Neccessarily Better Drivers Than Men. ScienceDaily.

- ^ Crash Data and Rates for Age-Sex Groups of Drivers, 1996, Ezio C. Cerrelli, January 1998, National Center for Statistics & Analysis - Research & Development

- ^ CFOI Charts, 1992–2006

- ^ Galdas P.M., Cheater F. & Marshall P. (2005) Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49, 616-23

- ^ a b George, A., “Reinventing honorable masculinity” Men and Masculinities

- ^ Smith, Jeremy Adam. The Daddy Shift. Boston: Beacon Press, 2009.

- ^ Stay-at-Home Dads, By Dawn Rosenberg McKay, About.com Guide

- ^ Men defy stereotypes in defining masculinity, August 26, 2008, Tri-City Psychology Services

- Bibliography

- Beynon, John (2002). "Chapter 4: Masculinities and the notion of 'crisis'". Masculinities and culture. Philadelphia: Open University Press. pp. 75–97. ISBN 978-0-335-19988-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reeser, Todd W. (2010). Masculinities in theory: an introduction. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6859-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Connell, R.W. (2001). "3". The Social Organization of Masculinity. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: Polity. ISBN 978-0-520-24698-0.

- Levine, Martin P. (1998). Gay Macho. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-4694-2.

- Stibbe, Arran. (2004). "Health and the Social Construction of Masculinity in Men's Health Magazine." Men and Masculinities; 7 (1) July, pp. 31–51.

- Strate, Lance "Beer Commercials: A Manual on Masculinity" Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

Further reading

- Present situation

- Arrindell, Willem A., Ph.D. (1 October 2005) "Masculine Gender Role Stress" Psychiatric Times Pg. 31

- Ashe, Fidelma (2007) The New Politics of Masculinity, London and New York: Routledge.

- Broom A. and Tovey P. (Eds) Men’s Health: Body, Identity and Social Context London; John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Burstin, Fay "What's Killing Men". Herald Sun (Melbourne, Australia). October 15, 2005.

- Canada, Geoffrey "Learning to Fight" Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

- Raewyn Connell: Masculinities (as Robert W. Connell), Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995 ISBN 0-7456-1469-8

- Courtenay, Will "Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health" Social Science and Medicine, yr: 2000 vol: 50 iss: 10 pg: 1385–1401

- bell hooks, We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, Taylor & Francis 2004, ISBN 0-415-96927-1

- Galdas P.M. and Cheater F.M. (2010) Indian and Pakistani men’s accounts of seeking medical help for angina and myocardial infarction in the UK: Constructions of marginalised masculinity or another version of hegemonic masculinity? Qualitative Research in Psychology

- Levant & Pollack (1995) A New Psychology of Men, New York: BasicBooks

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (2005): Why guys throw bombs. About terror and masculinity (pdf)

- Kaufman, Michael "The Construction of Masculinity and the Triad of Men's Violence". Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

- Mansfield, Harvey. Manliness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-10664-5

- Reeser, T. Masculinities in Theory, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Robinson, L. (October 21, 2005). Not just boys being boys: Brutal hazings are a product of a culture of masculinity defined by violence, aggression and domination. Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, Ontario).

- Stephenson, June (1995). Men are Not Cost Effective: Male Crime in America. ISBN 0-06-095098-6

- Walsh, Fintan. Male Trouble: Masculinity and the Performance of Crisis. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Williamson P. "Their own worst enemy" Nursing Times: 91 (48) 29 November 95 p 24–7

- Wray Herbert "Survival Skills" U.S. News & World Report Vol. 139, No. 11; Pg. 63 September 26, 2005

- "Masculinity for Boys"; published by UNESCO, New Delhi, 2006;

- Smith, Bonnie G., Hutchison, Beth. Gendering Disability. Rutgers University Press, 2004.

- History

- Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America, New York [etc.]: The Free Press 1996

- A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Mens History and Masculinity, edited by Earnestine Jenkins and Darlene Clark Hine, Indiana University press vol1: 1999, vol. 2: 2001

- Gary Taylor, Castration: An Abbreviated History of Western Manhood, Routledge 2002

- Klaus Theweleit, Male fantasies, Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1987 and Polity Press, 1987

- Peter N. Stearns, Be a Man!: Males in Modern Society, Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1990

- Shuttleworth, Russell. "Disabled Masculinity." Gendering Disability. Ed. Bonnie G. Smith and Beth Hutchison. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2004. 166-178.

External links

Bibliographic

- The Men's Bibliography, a comprehensive bibliography of writing on men, masculinities, gender and sexualities, listing over 16,700 works. (mainly from a constructionist perspective)

- Boyhood Studies, features a 2200+ bibliography of young masculinities.

Other

- Practical Manliness, A manly blog that applies "historical ideals to modern men".

- The ManKind Project of Chicago, supporting men in leading meaningful lives of integrity, accountability, responsibility, and emotional intelligence

- NIMH web pages on men and depression, talks about men and their depression and how to get help.

- Article entitled "Wounded Masculinity: Parsifal and The Fisher King Wound" The symbolism of the story as it relates to the Wounded Masculinity of Men by Richard Sanderson M.Ed., B.A.

- BULL, Print and online literary journal specializing in masculine fiction for a male audience.

- Art of Manliness, An online web magazine/blog dedicated to "reviving the lost art of manliness".

- The Masculinity Conspiracy, An online book critiquing constructions of masculinity.