Homestead Acts: Difference between revisions

Triangle23 (talk | contribs) ←Replaced content with 'The homestead act of 1862 happened in 1862. People came from everywhere and lived in the west. People died and lived. They made sod houses. Haha, you thought...' |

Thirdright (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by Triangle23 (talk) to last revision by Lugia2453 (HG) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2012}} |

|||

The homestead act of 1862 happened in 1862. People came from everywhere and lived in the west. People died and lived. They made sod houses. Haha, you thought you'd actually get real information. lozer |

|||

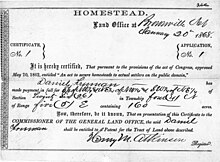

[[File:Freeman homestead-certificate.jpg|thumb|Certificate of homestead in Nebraska given under the Homestead Act, 1862.]] |

|||

The '''Homestead Acts''' were several [[United States federal law]]s that gave an applicant ownership of land, typically called a "homestead", at little or no cost. In the United States, this usually consisted of [[Land grants|grants]] totaling 160 acres (65 hectares, or one-fourth of a [[Section (United States land surveying)|section]]) of unappropriated (that is, reserved for no other purpose) [[federal land]] within the boundaries of the public land states. An extension of the ''[[Homestead principle|Homestead Principle]]'' in law, the United States Homestead Acts were originally proposed as an expression of the "[[Free Soil]]" policy of Northerners who wanted individual farmers to own and operate their own farms, as opposed to Southern slave-owners who could use gangs of [[slaves]] to economic advantage. |

|||

The first of the acts, the '''Homestead Act of 1862''', was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. government, including freed slaves; was 21 or older; or the head of a family, could file an application to claim a federal land grant. There was also a residency requirement. The '''[[Timber Culture Act]]''' granted 160 acres to a claimant who planted trees. The tract could be added to an existing homestead claim and had no residency requirement. The '''[[Kinkaid Act|Kincaid Amendment]]''' granted a full section (640 acres) to homesteaders in western Nebraska. The amended homestead act, the '''Enlarged Homestead Act''', was passed in 1909 and increased the acreage to 320. Another amended act, the '''Stock-Raising Homestead Act''', was passed in 1916 and again increased the land involved, this time to 640 acres. |

|||

==Background== |

|||

The first Homestead Act had originally been proposed by Northern Republicans, but had been repeatedly blocked for passage in Congress by Southern Democrats who wanted western lands open for slave-owners. After the Southern states seceded in 1861 and most of their representatives resigned from Congress, the [[History of the Republican Party (United States)|Republican Congress]] passed the long delayed bill. It was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862.<ref name="nps homestead">{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/home/faqs.htm|title=Homestead National Monument: Frequently Asked Questions|publisher=National Park Service|accessdate=May 26, 2009}}</ref> [[Daniel Freeman]] became the first person to file a claim under the new act. |

|||

Between 1862 and 1934, the federal government granted 1.6 million homesteads and distributed {{convert|270000000|acre|mi2}} of federal land for private ownership. This was a total of 10% of all land in the United States.<ref>[http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act/ The Homestead Act of 1862]. – Archives.gov</ref> Homesteading was discontinued in 1976, except in Alaska, where it continued until 1986. |

|||

About 40 percent of the applicants who started the process were able to complete it and obtain title to their homesteaded land.<ref>US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. [http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/bynumbers.htm “Homesteading by the Numbers”], accessed February 5, 2010.</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Wikisourcepar|Homestead Act}} |

|||

===Homestead Act of 1862=== |

|||

The "[[Yeoman|yeoman farmer]]" ideal of [[Jeffersonian democracy]] was still a powerful influence in American politics during the 1840–1850s, with many politicians believing a homestead act would help increase the number of "virtuous yeomen". The Free Soil Party of 1848–52, and the new Republican Party after 1854, demanded that the new lands opening up in the west be made available to independent farmers, rather than wealthy planters who would develop it with the use of slaves forcing the yeomen farmers onto marginal lands.<ref>Eric Foner; ''Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War''; 1970.</ref> Southern Democrats had continually fought (and defeated) previous homestead law proposals, as they feared free land would attract [[European]] immigrants and poor Southern whites to the west.<ref>Charles C. Bolton; ''Poor Whites of the Antebellum South: Tenants and Laborers in Central North Carolina and Northeast Mississippi''; 1993; p. 67.</ref><ref>Phillips; p. 2000.</ref><ref>McPherson; p. 193.</ref> After the South seceded and their delegates left Congress in 1861, the Republicans and other supporters from the upper South passed a homestead act.<ref name="mcpherson">McPherson; pp. 450–451.</ref> |

|||

The intent of the first Homestead Act, passed in 1862, was to liberalize the homesteading requirements of the [[Preemption Act of 1841]]. Its leading advocates were [[Andrew Johnson]],<ref>Trefousse; p. 42.</ref> [[George Henry Evans]] and [[Horace Greeley]].<ref>McElroy; p.1.</ref><ref>[http://www.tulane.edu/~latner/Greeley.html "Horace Greeley"]; Tulane University; August 13, 1999[ retrieved 11-22-2007.</ref> |

|||

The law (and those following it) required a three step procedure: file an application, [[Land improvement|improve]] the land, and file for [[deed]] of title. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. government (including freed slaves) and was at least 21 years old or the head of a household, could file an application to claim a federal land grant. The occupant had to reside on the land for five years, and show evidence of having made improvements. |

|||

===The Timber Culture Act of 1873=== |

|||

{{Main|Timber Culture Act}} |

|||

The Timber Culture Act granted up to 160 acres of land to a homesteader who would plant trees over a period of several years. This quarter-section could be added to an existing homestead claim, offering a total of 320 acres to a settler. |

|||

====Kinkaid Ammendment of 1904==== |

|||

{{Main|Kinkaid Act}} |

|||

Recognizing that arid lands west of the 100th meridian, which passes through central Nebraska, required more than 160 acres for a claimant to support a family, Congress passed the Kinkaid Act which granted larger homestead tracts, up to 640 acres, to homesteaders in western Nebraska. |

|||

===Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909=== |

|||

Because by the early 1900s much of the prime low-lying [[Alluvial plain|alluvial land]] along rivers had been homesteaded, the ''Enlarged Homestead Act'' was passed in 1909. To enable [[dryland farming]], it increased the number of acres for a homestead to {{convert|320|acre|km2}} given to farmers who accepted more marginal lands (especially in the Great Plains), which could not be easily irrigated.<ref name="blm06">[http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/wo/Minerals Realty and Resource Protection /bmps.Par.41235.File.dat/Split%20Estate%20Presentation%202006.pdf Split EstatePrivate Surface / Public Minerals: What Does it Mean to You?], a 2006 [[Bureau of Land Management]] presentation</ref> |

|||

A massive influx of these new farmers, combined with inappropriate cultivation techniques and misunderstanding of the ecology, led to immense land erosion and eventually the [[Dust Bowl]] of the 1930s.<ref>[http://www.publiclands.org/museum/story/story10.htm List of Laws about Lands]. – The Public Lands Museum</ref><ref>Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. – [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=286699 "U.S. Land Policy, Property Rights, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s"], Social Science Electronic Publishing, September 2001.</ref> |

|||

===The Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916=== |

|||

{{Main|Stock-Raising Homestead Act}} |

|||

In 1916, the ''Stock-Raising Homestead Act'' was passed for settlers seeking {{convert|640|acre}} of [[public land]] for [[ranch]]ing purposes.<ref name="blm06"/> |

|||

==Homesteading requirements== |

|||

The Homestead Acts had few qualifying requirements. A ''homesteader'' <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/homesteader|title= Homesteader|publisher= The Free Dictionary By Farlex|accessdate=2012-29-06}}</ref> had to be the head of the household or at least twenty-one years old. They had to live on the designated land, build a home, make improvements, and farm it for a minimum of five years.<ref>{{cite web| url= http://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-homestead.html|title= AMERICAN HISTORY The Homestead Act - Creating Prosperity in America |publisher= Legends of America |accessdate=2012-29-06}}</ref> The filing fee was eighteen dollars (or ten to temporarily hold a claim to the land).<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/abouthomesteadactlaw.htm |title= About the Homestead Act |publisher= National Park Service |accessdate=2012-29-06}}</ref> |

|||

Immigrants, farmers without their own land, single women, and former slaves could all qualify. |

|||

==End of homesteading== |

|||

[[File:Dugout home2.jpg|right|thumb|[[Dugout (shelter)|Dugout]] home from a homestead near [[Pie Town, New Mexico]], 1940.]] |

|||

The [[Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976]] ended homesteading;<ref name="florida">{{cite web|url=http://www.netside.net/~c3i/act.htm|title=The Florida Homestead Act of 1862|year=2006|accessdate=November 22, 2007|publisher=Florida Homestead Services}} (paragraphs.3,6&13) (Includes data '''on the U.S. Homestead Act)</ref><ref> |

|||

{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-3xliUQx6boC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=end+homesteading|title=Arctic Homestead: The True Story of a Family's Survival and Courage....|first=Norma|last=Cobb|publisher=St. Martin's Press|year=2000 |

|||

|accessdate=November 22, 2007|isbn=0-312-28379-2|pages=21}} |

|||

</ref> by that time, federal government policy had shifted to retaining control of western public lands. The only exception to this new policy was in [[Alaska]], for which the law allowed homesteading until 1986.<ref name="florida"/> |

|||

The last claim under this Act was made by Ken Deardorff for {{convert|80|acre|ha}} of land on the [[Stony River (Alaska)|Stony River]] in southwestern Alaska. He fulfilled all requirements of the homestead act in 1979 but did not receive his deed until May 1988. He is the last person to receive title to land claimed under the homestead acts.<ref name="kenneth">{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/lasthomesteader.htm|title=The Last Homesteader|publisher=National Park Service|year=2006 |

|||

|accessdate=November 22, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

==Criticism== |

|||

The homestead acts were much abused.<ref name="florida"/> Although the intent was to grant land for agriculture, in the arid areas east of the [[Rocky Mountains]], {{convert|640|acre|km2}} was generally too little land for a viable farm (at least prior to major federal public investments in irrigation projects). In these areas, people manipulated the provisions of the act to gain control of resources, especially water. A common scheme was for an individual, acting as a front for a large cattle operation, to file for a homestead surrounding a water source, under the pretense that the land was to be used as a farm. Once the land was granted, other cattle ranchers would be denied the use of that water source, effectively closing off the adjacent public land to competition. That method was also used by large businesses and speculators to gain ownership of timber and oil-producing land. The federal government charged royalties for extraction of these resources from public lands. On the other hand, homesteading schemes were generally pointless for land containing "locatable minerals," such as gold and silver, which could be controlled through mining claims under the [[Mining Act of 1872]], for which the federal government did not charge royalties. |

|||

The government developed no systematic method to evaluate claims under the homestead acts. Land offices relied on affidavits from witnesses that the claimant had lived on the land for the required period of time and made the required improvements. In practice, some of these witnesses were bribed or otherwise colluded with the claimant. |

|||

Although not necessarily fraud, it was common practice for the eligible children of a large family to claim nearby land as soon as possible. After a few generations, a family could build up a sizable estate.<ref name="Hansen">Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=460622 "Small Farms, Externalities, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s"], ''Journal of Political Economy'', Volume: 112(3). – pp.665–94. – 21 November 2003</ref> While the homesteads were criticized as too small for the environmental conditions on the Great Plains, a homesteader using 19th-century animal-powered tilling and harvesting could not have cultivated the 1500 acres later recommended for dry land farming. Some scholars believe the acreage limits were reasonable when the act was written, but reveal that no one understood the physical conditions of the plains.<ref name="Hansen"/> |

|||

According to [[Hugh Nibley]], much of the rain forest west of [[Portland, Oregon]] was acquired by the [[Oregon Lumber Company]] by illegal claims under the Act.<ref>See Nibley, Hugh. ''Approaching Zion'' (The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Vol 9), p. 469. Nibley's grandfather, [[Charles W. Nibley]] made his fortune in Oregon lumber, among other resourcesthings.</ref> |

|||

==Related acts in other countries== |

|||

Canada passed a similar act, with some modifications, in the form of the [[Dominion Lands Act]]. Similar acts{{spaced ndash}} usually termed the [[Selection (Australian history)|selection acts]]{{spaced ndash}}were passed in the various Australian colonies in the 1860s, beginning in 1861 in [[New South Wales]]. |

|||

== Popular culture == |

|||

* [[Laura Ingalls Wilder]]'s ''[[Little House on the Prairie]]'' series describes her father and family claiming a homestead in [[Kansas]], and later [[Dakota Territory]]. |

|||

* [[Willa Cather]]'s novels, ''[[O Pioneers!]]'' and ''[[My Ántonia]]'', feature families homesteading on the Great Plains. |

|||

* Kirby Larson's young adult novel, ''Hattie Big Sky'', explores one woman's attempts to "improve" on her family's homestead before the deadline to retain her rights. |

|||

* The [[Rodgers and Hammerstein]] musical ''[[Oklahoma]]'' is based in the [[Oklahoma land rush]]. |

|||

* The 1962 [[Elvis Presley]] musical film, ''[[Follow That Dream]]'', adapted from ''[[Pioneer, Go Home!]]'' (1959), features a family that homesteads in Florida. |

|||

* The movie ''[[Far and Away]],'' starring [[Tom Cruise]] and [[Nicole Kidman]], centers on the main characters' struggle to "obtain their 160 acres." |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Donation Land Claim Act of 1850]] |

|||

* [[Land Act of 1804]] |

|||

* [[Land run]] |

|||

* [[Military Tract of 1812]] |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

<div class="references-small"> |

|||

*Dick, Everett, 1970. ''The Lure of the Land: A Social History of the Public Lands from the Articles of Confederation to the New Deal''. |

|||

*Gates, Paul W., 1996. ''The Jeffersonian Dream: Studies in the History of American Land Policy and Development'. |

|||

*Hyman, Harold M., 1986. ''American Singularity: The 1787 Northwest Ordinance, the 1862 Homestead and Morrill Acts, and the 1944 G.I. Bill''. |

|||

* Lause, Mark A., 2005. ''Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community''. |

|||

* Phillips, Sarah T., 2000, "Antebellum Agricultural Reform, Republican Ideology, and Sectional Tension." ''Agricultural History 74(4)'': 799–822. ISSN 0002-1482 |

|||

* [[Stephen A. Douglas Puter|Puter, Stephen A. Douglas]]; Stevens, Horace – 1907 "Looters of the Public Domain". |

|||

* Richardson, Heather Cox, 1997. ''The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War''. |

|||

* Robbins, Roy M., 1942. ''Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain, 1776–1936''. |

|||

* Smith, Henry Nash. ''Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth''. New York: Vintage, 1959. |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Trefousse |first= Hans L. |title=Andrew Johnson: A Biography |year=1989 |ISBN= 0-393-31742-0 |publisher=Norton}} |

|||

</div> |

|||

==References and notes== |

|||

Specific references: |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

General references: |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.fff.org/freedom/0501e.asp|title=The Free-Soil Movement, Part 1|publisher=The Future of Freedom Foundation|first=Wendy|last=McElroy|year=2001|accessdate=November 22, 2007}} |

|||

* {{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-uuEA7xIUHUC&pg=PA194&lpg=PA194&dq=southern+opposition+homesteading|title=Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era|first=James M.|last=McPherson|year=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0-19-516895-X|pages=193–195}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{wikisource}} |

|||

* [http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Homestead.html Homestead Act]. – [[Library of Congress]] |

|||

* [http://www.nps.gov/home/index.htm Homestead National Monument of America]. – [[National Park Service]] |

|||

* [http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/abouthomesteadactlaw.htm "About the Homestead Act"]. – [[National Park Service]] |

|||

* [http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act/index.html Homestead Act of 1862]. – [[National Archives and Records Administration]] |

|||

* [http://content.lib.washington.edu/cmpweb/exhibits/homesteading/index.html Homesteaders and Pioneers on the Olympic Peninsula]. – Olympic Peninsula Community Museum. – [[University of Washington]]. – <small>Online museum exhibit that documents the history of several families who moved to the Olympic Peninsula following the Homestead Act of 1862</small> |

|||

*[http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/67hornbek/67hornbek.htm "Adeline Hornbek and the Homestead Act: A Colorado Success Story"]. – National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan. – [[National Park Service]] |

|||

* [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/H/HO022.html Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Homestead Act] |

|||

* [http://www.prairiepublic.org/television/prairie-public-on-demand/homesteading/ Homesteading] Documentary produced by [[Prairie Public Television]] |

|||

{{Wild West}} |

|||

[[Category:1862 in law]] |

|||

[[Category:1909 in law]] <!-- Enlarged Homestead Act --> |

|||

[[Category:Economic history of the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:American Old West]] |

|||

[[Category:United States federal public land legislation]] |

|||

[[Category:History of the United States (1849–1865)]] |

|||

[[Category:1862 in American politics]] |

|||

[[Category:37th United States Congress]] |

|||

[[Category:Aboriginal title in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:History of agriculture in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma]] |

|||

[[Category:Oklahoma Territory]] |

|||

[[de:Homestead Act]] |

|||

[[es:Ley de Asentamientos Rurales]] |

|||

[[fr:Homestead Act]] |

|||

[[ko:자영 농지법]] |

|||

[[it:Homestead Act of 1862]] |

|||

[[nl:Homestead act]] |

|||

[[ja:ホームステッド法]] |

|||

[[pl:Ustawa o gospodarstwach rolnych]] |

|||

[[pt:Lei da Propriedade Rural]] |

|||

[[ru:Закон о гомстедах]] |

|||

[[sv:Homestead]] |

|||

[[uk:Акт про гомстеди]] |

|||

[[zh:宅地法]] |

|||

Revision as of 22:56, 28 November 2012

The Homestead Acts were several United States federal laws that gave an applicant ownership of land, typically called a "homestead", at little or no cost. In the United States, this usually consisted of grants totaling 160 acres (65 hectares, or one-fourth of a section) of unappropriated (that is, reserved for no other purpose) federal land within the boundaries of the public land states. An extension of the Homestead Principle in law, the United States Homestead Acts were originally proposed as an expression of the "Free Soil" policy of Northerners who wanted individual farmers to own and operate their own farms, as opposed to Southern slave-owners who could use gangs of slaves to economic advantage.

The first of the acts, the Homestead Act of 1862, was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. government, including freed slaves; was 21 or older; or the head of a family, could file an application to claim a federal land grant. There was also a residency requirement. The Timber Culture Act granted 160 acres to a claimant who planted trees. The tract could be added to an existing homestead claim and had no residency requirement. The Kincaid Amendment granted a full section (640 acres) to homesteaders in western Nebraska. The amended homestead act, the Enlarged Homestead Act, was passed in 1909 and increased the acreage to 320. Another amended act, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act, was passed in 1916 and again increased the land involved, this time to 640 acres.

Background

The first Homestead Act had originally been proposed by Northern Republicans, but had been repeatedly blocked for passage in Congress by Southern Democrats who wanted western lands open for slave-owners. After the Southern states seceded in 1861 and most of their representatives resigned from Congress, the Republican Congress passed the long delayed bill. It was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862.[1] Daniel Freeman became the first person to file a claim under the new act.

Between 1862 and 1934, the federal government granted 1.6 million homesteads and distributed 270,000,000 acres (420,000 sq mi) of federal land for private ownership. This was a total of 10% of all land in the United States.[2] Homesteading was discontinued in 1976, except in Alaska, where it continued until 1986.

About 40 percent of the applicants who started the process were able to complete it and obtain title to their homesteaded land.[3]

History

Homestead Act of 1862

The "yeoman farmer" ideal of Jeffersonian democracy was still a powerful influence in American politics during the 1840–1850s, with many politicians believing a homestead act would help increase the number of "virtuous yeomen". The Free Soil Party of 1848–52, and the new Republican Party after 1854, demanded that the new lands opening up in the west be made available to independent farmers, rather than wealthy planters who would develop it with the use of slaves forcing the yeomen farmers onto marginal lands.[4] Southern Democrats had continually fought (and defeated) previous homestead law proposals, as they feared free land would attract European immigrants and poor Southern whites to the west.[5][6][7] After the South seceded and their delegates left Congress in 1861, the Republicans and other supporters from the upper South passed a homestead act.[8]

The intent of the first Homestead Act, passed in 1862, was to liberalize the homesteading requirements of the Preemption Act of 1841. Its leading advocates were Andrew Johnson,[9] George Henry Evans and Horace Greeley.[10][11]

The law (and those following it) required a three step procedure: file an application, improve the land, and file for deed of title. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. government (including freed slaves) and was at least 21 years old or the head of a household, could file an application to claim a federal land grant. The occupant had to reside on the land for five years, and show evidence of having made improvements.

The Timber Culture Act of 1873

The Timber Culture Act granted up to 160 acres of land to a homesteader who would plant trees over a period of several years. This quarter-section could be added to an existing homestead claim, offering a total of 320 acres to a settler.

Kinkaid Ammendment of 1904

Recognizing that arid lands west of the 100th meridian, which passes through central Nebraska, required more than 160 acres for a claimant to support a family, Congress passed the Kinkaid Act which granted larger homestead tracts, up to 640 acres, to homesteaders in western Nebraska.

Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909

Because by the early 1900s much of the prime low-lying alluvial land along rivers had been homesteaded, the Enlarged Homestead Act was passed in 1909. To enable dryland farming, it increased the number of acres for a homestead to 320 acres (1.3 km2) given to farmers who accepted more marginal lands (especially in the Great Plains), which could not be easily irrigated.[12]

A massive influx of these new farmers, combined with inappropriate cultivation techniques and misunderstanding of the ecology, led to immense land erosion and eventually the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.[13][14]

The Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916

In 1916, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act was passed for settlers seeking 640 acres (260 ha) of public land for ranching purposes.[12]

Homesteading requirements

The Homestead Acts had few qualifying requirements. A homesteader [15] had to be the head of the household or at least twenty-one years old. They had to live on the designated land, build a home, make improvements, and farm it for a minimum of five years.[16] The filing fee was eighteen dollars (or ten to temporarily hold a claim to the land).[17]

Immigrants, farmers without their own land, single women, and former slaves could all qualify.

End of homesteading

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 ended homesteading;[18][19] by that time, federal government policy had shifted to retaining control of western public lands. The only exception to this new policy was in Alaska, for which the law allowed homesteading until 1986.[18]

The last claim under this Act was made by Ken Deardorff for 80 acres (32 ha) of land on the Stony River in southwestern Alaska. He fulfilled all requirements of the homestead act in 1979 but did not receive his deed until May 1988. He is the last person to receive title to land claimed under the homestead acts.[20]

Criticism

The homestead acts were much abused.[18] Although the intent was to grant land for agriculture, in the arid areas east of the Rocky Mountains, 640 acres (2.6 km2) was generally too little land for a viable farm (at least prior to major federal public investments in irrigation projects). In these areas, people manipulated the provisions of the act to gain control of resources, especially water. A common scheme was for an individual, acting as a front for a large cattle operation, to file for a homestead surrounding a water source, under the pretense that the land was to be used as a farm. Once the land was granted, other cattle ranchers would be denied the use of that water source, effectively closing off the adjacent public land to competition. That method was also used by large businesses and speculators to gain ownership of timber and oil-producing land. The federal government charged royalties for extraction of these resources from public lands. On the other hand, homesteading schemes were generally pointless for land containing "locatable minerals," such as gold and silver, which could be controlled through mining claims under the Mining Act of 1872, for which the federal government did not charge royalties.

The government developed no systematic method to evaluate claims under the homestead acts. Land offices relied on affidavits from witnesses that the claimant had lived on the land for the required period of time and made the required improvements. In practice, some of these witnesses were bribed or otherwise colluded with the claimant.

Although not necessarily fraud, it was common practice for the eligible children of a large family to claim nearby land as soon as possible. After a few generations, a family could build up a sizable estate.[21] While the homesteads were criticized as too small for the environmental conditions on the Great Plains, a homesteader using 19th-century animal-powered tilling and harvesting could not have cultivated the 1500 acres later recommended for dry land farming. Some scholars believe the acreage limits were reasonable when the act was written, but reveal that no one understood the physical conditions of the plains.[21]

According to Hugh Nibley, much of the rain forest west of Portland, Oregon was acquired by the Oregon Lumber Company by illegal claims under the Act.[22]

Related acts in other countries

Canada passed a similar act, with some modifications, in the form of the Dominion Lands Act. Similar acts – usually termed the selection acts – were passed in the various Australian colonies in the 1860s, beginning in 1861 in New South Wales.

Popular culture

- Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie series describes her father and family claiming a homestead in Kansas, and later Dakota Territory.

- Willa Cather's novels, O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, feature families homesteading on the Great Plains.

- Kirby Larson's young adult novel, Hattie Big Sky, explores one woman's attempts to "improve" on her family's homestead before the deadline to retain her rights.

- The Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma is based in the Oklahoma land rush.

- The 1962 Elvis Presley musical film, Follow That Dream, adapted from Pioneer, Go Home! (1959), features a family that homesteads in Florida.

- The movie Far and Away, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, centers on the main characters' struggle to "obtain their 160 acres."

See also

Further reading

- Dick, Everett, 1970. The Lure of the Land: A Social History of the Public Lands from the Articles of Confederation to the New Deal.

- Gates, Paul W., 1996. The Jeffersonian Dream: Studies in the History of American Land Policy and Development'.

- Hyman, Harold M., 1986. American Singularity: The 1787 Northwest Ordinance, the 1862 Homestead and Morrill Acts, and the 1944 G.I. Bill.

- Lause, Mark A., 2005. Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community.

- Phillips, Sarah T., 2000, "Antebellum Agricultural Reform, Republican Ideology, and Sectional Tension." Agricultural History 74(4): 799–822. ISSN 0002-1482

- Puter, Stephen A. Douglas; Stevens, Horace – 1907 "Looters of the Public Domain".

- Richardson, Heather Cox, 1997. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War.

- Robbins, Roy M., 1942. Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain, 1776–1936.

- Smith, Henry Nash. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. New York: Vintage, 1959.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. Norton. ISBN 0-393-31742-0.

References and notes

Specific references:

- ^ "Homestead National Monument: Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ The Homestead Act of 1862. – Archives.gov

- ^ US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. “Homesteading by the Numbers”, accessed February 5, 2010.

- ^ Eric Foner; Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War; 1970.

- ^ Charles C. Bolton; Poor Whites of the Antebellum South: Tenants and Laborers in Central North Carolina and Northeast Mississippi; 1993; p. 67.

- ^ Phillips; p. 2000.

- ^ McPherson; p. 193.

- ^ McPherson; pp. 450–451.

- ^ Trefousse; p. 42.

- ^ McElroy; p.1.

- ^ "Horace Greeley"; Tulane University; August 13, 1999[ retrieved 11-22-2007.

- ^ a b Realty and Resource Protection /bmps.Par.41235.File.dat/Split%20Estate%20Presentation%202006.pdf Split EstatePrivate Surface / Public Minerals: What Does it Mean to You?, a 2006 Bureau of Land Management presentation

- ^ List of Laws about Lands. – The Public Lands Museum

- ^ Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. – "U.S. Land Policy, Property Rights, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s", Social Science Electronic Publishing, September 2001.

- ^ "Homesteader". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved 2012-29-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "AMERICAN HISTORY The Homestead Act - Creating Prosperity in America". Legends of America. Retrieved 2012-29-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "About the Homestead Act". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-29-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "The Florida Homestead Act of 1862". Florida Homestead Services. 2006. Retrieved November 22, 2007. (paragraphs.3,6&13) (Includes data on the U.S. Homestead Act)

- ^ Cobb, Norma (2000). Arctic Homestead: The True Story of a Family's Survival and Courage... St. Martin's Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-312-28379-2. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "The Last Homesteader". National Park Service. 2006. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. "Small Farms, Externalities, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s", Journal of Political Economy, Volume: 112(3). – pp.665–94. – 21 November 2003

- ^ See Nibley, Hugh. Approaching Zion (The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Vol 9), p. 469. Nibley's grandfather, Charles W. Nibley made his fortune in Oregon lumber, among other resourcesthings.

General references:

- McElroy, Wendy (2001). "The Free-Soil Movement, Part 1". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- McPherson, James M. (1998). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. pp. 193–195. ISBN 0-19-516895-X.

External links

- Homestead Act. – Library of Congress

- Homestead National Monument of America. – National Park Service

- "About the Homestead Act". – National Park Service

- Homestead Act of 1862. – National Archives and Records Administration

- Homesteaders and Pioneers on the Olympic Peninsula. – Olympic Peninsula Community Museum. – University of Washington. – Online museum exhibit that documents the history of several families who moved to the Olympic Peninsula following the Homestead Act of 1862

- "Adeline Hornbek and the Homestead Act: A Colorado Success Story". – National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan. – National Park Service

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Homestead Act

- Homesteading Documentary produced by Prairie Public Television

- 1862 in law

- 1909 in law

- Economic history of the United States

- American Old West

- United States federal public land legislation

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- 1862 in American politics

- 37th United States Congress

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- History of agriculture in the United States

- Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma

- Oklahoma Territory