Leadership: Difference between revisions

KhabarNegar (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 209: | Line 209: | ||

{{Main|Narcissistic leadership}} |

{{Main|Narcissistic leadership}} |

||

[[Narcissism|Narcissistic]] leadership is a leadership style in which the leader is only interested in him/herself. Their priority is themselves - at the expense of their people/group members. This leader exhibits the characteristics of a narcissist: arrogance, dominance and hostility. It is a common leadership style. The [[narcissism]] may range from anywhere between healthy and destructive. To [[critics]], "narcissistic leadership (preferably destructive) is driven by unyielding arrogance, self-absorption, and a personal [[egotistic]] need for [[Power (social and political)|power]] and [[Narcissistic supply|admiration]]."<ref>Linda L. Neider/Chester A. Schriesheim, ''The Dark Side of Management'' (2010) p. 29</ref> |

[[Narcissism|Narcissistic]] leadership is a leadership style in which the leader is only interested in him/herself. Their priority is themselves - at the expense of their people/group members. This leader exhibits the characteristics of a narcissist: arrogance, dominance and hostility. It is a common leadership style. The [[narcissism]] may range from anywhere between healthy and destructive. To [[critics]], "narcissistic leadership (preferably destructive) is driven by unyielding arrogance, self-absorption, and a personal [[egotistic]] need for [[Power (social and political)|power]] and [[Narcissistic supply|admiration]]."<ref>Linda L. Neider/Chester A. Schriesheim, ''The Dark Side of Management'' (2010) p. 29</ref> |

||

where does it happens |

|||

===Toxic leadership=== |

===Toxic leadership=== |

||

Revision as of 14:39, 5 April 2013

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Leadership has been described as “a process of social influence in which one person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task".[1] Other in-depth definitions of leadership have also emerged.

Leadership is "organizing a group of people to achieve a common goal". The leader may or may not have any formal authority. Studies of leadership have produced theories involving traits,[2] situational interaction, function, behavior, power, vision and values,[3] charisma, and intelligence, among others. Somebody whom people follow: somebody who guides or directs others.

Theories

Early western history

The search for the characteristics or traits of leaders has been ongoing for centuries. History's greatest philosophical writings from Plato's Republic to Plutarch's Lives have explored the question "What qualities distinguish an individual as a leader?" Underlying this search was the early recognition of the importance of leadership and the assumption that leadership is rooted in the characteristics that certain individuals possess. This idea that leadership is based on individual attributes is known as the "trait theory of leadership".

The trait theory was explored at length in a number of works in the 19th century. Most notable are the writings of Thomas Carlyle and Francis Galton, whose works have prompted decades of research.[4] In Heroes and Hero Worship (1841), Carlyle identified the talents, skills, and physical characteristics of men who rose to power. In Galton's Hereditary Genius (1869), he examined leadership qualities in the families of powerful men. After showing that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when moving from first degree to second degree relatives, Galton concluded that leadership was inherited. In other words, leaders were born, not developed. Both of these notable works lent great initial support for the notion that leadership is rooted in characteristics of the leader.

Rise of alternative theories

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, however, a series of qualitative reviews of these studies (e.g., Bird, 1940;[5] Stogdill, 1948;[6] Mann, 1959[7]) prompted researchers to take a drastically different view of the driving forces behind leadership. In reviewing the extant literature, Stogdill and Mann found that while some traits were common across a number of studies, the overall evidence suggested that persons who are leaders in one situation may not necessarily be leaders in other situations. Subsequently, leadership was no longer characterized as an enduring individual trait, as situational approaches (see alternative leadership theories below) posited that individuals can be effective in certain situations, but not others. This approach dominated much of the leadership theory and research for the next few decades.

Reemergence of trait theory

New methods and measurements were developed after these influential reviews that would ultimately reestablish the trait theory as a viable approach to the study of leadership. For example, improvements in researchers' use of the round robin research design methodology allowed researchers to see that individuals can and do emerge as leaders across a variety of situations and tasks.[8] Additionally, during the 1980s statistical advances allowed researchers to conduct meta-analyses, in which they could quantitatively analyze and summarize the findings from a wide array of studies. This advent allowed trait theorists to create a comprehensive picture of previous leadership research rather than rely on the qualitative reviews of the past. Equipped with new methods, leadership researchers revealed the following:

- Individuals can and do emerge as leaders across a variety of situations and tasks.[8]

- Significant relationships exist between leadership and such individual traits as:

While the trait theory of leadership has certainly regained popularity, its reemergence has not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in sophisticated conceptual frameworks.[16]

Specifically, Zaccaro (2007)[16] noted that trait theories still:

- focus on a small set of individual attributes such as Big Five personality traits, to the neglect of cognitive abilities, motives, values, social skills, expertise, and problem-solving skills;

- fail to consider patterns or integrations of multiple attributes;

- do not distinguish between those leader attributes that are generally not malleable over time and those that are shaped by, and bound to, situational influences;

- do not consider how stable leader attributes account for the behavioral diversity necessary for effective leadership.

Attribute pattern approach

Considering the criticisms of the trait theory outlined above, several researchers have begun to adopt a different perspective of leader individual differences—the leader attribute pattern approach.[15][17][18][19][20] In contrast to the traditional approach, the leader attribute pattern approach is based on theorists' arguments that the influence of individual characteristics on outcomes is best understood by considering the person as an integrated totality rather than a summation of individual variables.[19][21] In other words, the leader attribute pattern approach argues that integrated constellations or combinations of individual differences may explain substantial variance in both leader emergence and leader effectiveness beyond that explained by single attributes, or by additive combinations of multiple attributes.

Behavioral and style theories

In response to the early criticisms of the trait approach, theorists began to research leadership as a set of behaviors, evaluating the behavior of successful leaders, determining a behavior taxonomy, and identifying broad leadership styles.[22] David McClelland, for example, posited that leadership takes a strong personality with a well-developed positive ego. To lead, self-confidence and high self-esteem are useful, perhaps even essential.[23]

Kurt Lewin, Ronald Lipitt, and Ralph White developed in 1939 the seminal work on the influence of leadership styles and performance. The researchers evaluated the performance of groups of eleven-year-old boys under different types of work climate. In each, the leader exercised his influence regarding the type of group decision making, praise and criticism (feedback), and the management of the group tasks (project management) according to three styles: authoritarian, democratic, and laissez-faire.[24]

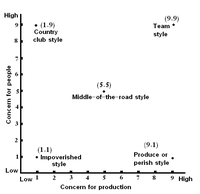

The managerial grid model is also based on a behavioral theory. The model was developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton in 1964 and suggests five different leadership styles, based on the leaders' concern for people and their concern for goal achievement.[25]

Positive reinforcement

B.F. Skinner is the father of behavior modification and developed the concept of positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement occurs when a positive stimulus is presented in response to a behavior, increasing the likelihood of that behavior in the future.[26] The following is an example of how positive reinforcement can be used in a business setting. Assume praise is a positive reinforcer for a particular employee. This employee does not show up to work on time every day. The manager of this employee decides to praise the employee for showing up on time every day the employee actually shows up to work on time. As a result, the employee comes to work on time more often because the employee likes to be praised. In this example, praise (the stimulus) is a positive reinforcer for this employee because the employee arrives at work on time (the behavior) more frequently after being praised for showing up to work on time.

The use of positive reinforcement is a successful and growing technique used by leaders to motivate and attain desired behaviors from subordinates. Organizations such as Frito-Lay, 3M, Goodrich, Michigan Bell, and Emery Air Freight have all used reinforcement to increase productivity.[27] Empirical research covering the last 20 years suggests that reinforcement theory has a 17 percent increase in performance. Additionally, many reinforcement techniques such as the use of praise are inexpensive, providing higher performance for lower costs.

Situational and contingency theories

Situational theory also appeared as a reaction to the trait theory of leadership. Social scientists argued that history was more than the result of intervention of great men as Carlyle suggested. Herbert Spencer (1884) (and Karl Marx) said that the times produce the person and not the other way around.[28] This theory assumes that different situations call for different characteristics; according to this group of theories, no single optimal psychographic profile of a leader exists. According to the theory, "what an individual actually does when acting as a leader is in large part dependent upon characteristics of the situation in which he functions."[29]

Some theorists started to synthesize the trait and situational approaches. Building upon the research of Lewin et al., academics began to normalize the descriptive models of leadership climates, defining three leadership styles and identifying which situations each style works better in. The authoritarian leadership style, for example, is approved in periods of crisis but fails to win the "hearts and minds" of followers in day-to-day management; the democratic leadership style is more adequate in situations that require consensus building; finally, the laissez-faire leadership style is appreciated for the degree of freedom it provides, but as the leaders do not "take charge", they can be perceived as a failure in protracted or thorny organizational problems.[30] Thus, theorists defined the style of leadership as contingent to the situation, which is sometimes classified as contingency theory. Four contingency leadership theories appear more prominently in recent years: Fiedler contingency model, Vroom-Yetton decision model, the path-goal theory, and the Hersey-Blanchard situational theory.

The Fiedler contingency model bases the leader's effectiveness on what Fred Fiedler called situational contingency. This results from the interaction of leadership style and situational favorability (later called situational control). The theory defined two types of leader: those who tend to accomplish the task by developing good relationships with the group (relationship-oriented), and those who have as their prime concern carrying out the task itself (task-oriented).[31] According to Fiedler, there is no ideal leader. Both task-oriented and relationship-oriented leaders can be effective if their leadership orientation fits the situation. When there is a good leader-member relation, a highly structured task, and high leader position power, the situation is considered a "favorable situation". Fiedler found that task-oriented leaders are more effective in extremely favorable or unfavorable situations, whereas relationship-oriented leaders perform best in situations with intermediate favorability.

Victor Vroom, in collaboration with Phillip Yetton (1973)[32] and later with Arthur Jago (1988),[33] developed a taxonomy for describing leadership situations, which was used in a normative decision model where leadership styles were connected to situational variables, defining which approach was more suitable to which situation.[34] This approach was novel because it supported the idea that the same manager could rely on different group decision making approaches depending on the attributes of each situation. This model was later referred to as situational contingency theory.[35]

The path-goal theory of leadership was developed by Robert House (1971) and was based on the expectancy theory of Victor Vroom.[36] According to House, the essence of the theory is "the meta proposition that leaders, to be effective, engage in behaviors that complement subordinates' environments and abilities in a manner that compensates for deficiencies and is instrumental to subordinate satisfaction and individual and work unit performance".[37] The theory identifies four leader behaviors, achievement-oriented, directive, participative, and supportive, that are contingent to the environment factors and follower characteristics. In contrast to the Fiedler contingency model, the path-goal model states that the four leadership behaviors are fluid, and that leaders can adopt any of the four depending on what the situation demands. The path-goal model can be classified both as a contingency theory, as it depends on the circumstances, and as a transactional leadership theory, as the theory emphasizes the reciprocity behavior between the leader and the followers.

The situational leadership model proposed by Hersey and Blanchard suggests four leadership-styles and four levels of follower-development. For effectiveness, the model posits that the leadership-style must match the appropriate level of follower-development. In this model, leadership behavior becomes a function not only of the characteristics of the leader, but of the characteristics of followers as well.[38]

Functional theory

Functional leadership theory (Hackman & Walton, 1986; McGrath, 1962; Adair, 1988; Kouzes & Posner, 1995) is a particularly useful theory for addressing specific leader behaviors expected to contribute to organizational or unit effectiveness. This theory argues that the leader's main job is to see that whatever is necessary to group needs is taken care of; thus, a leader can be said to have done their job well when they have contributed to group effectiveness and cohesion (Fleishman et al., 1991; Hackman & Wageman, 2005; Hackman & Walton, 1986). While functional leadership theory has most often been applied to team leadership (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001), it has also been effectively applied to broader organizational leadership as well (Zaccaro, 2001). In summarizing literature on functional leadership (see Kozlowski et al. (1996), Zaccaro et al. (2001), Hackman and Walton (1986), Hackman & Wageman (2005), Morgeson (2005)), Klein, Zeigert, Knight, and Xiao (2006) observed five broad functions a leader performs when promoting organization's effectiveness. These functions include environmental monitoring, organizing subordinate activities, teaching and coaching subordinates, motivating others, and intervening actively in the group's work.

A variety of leadership behaviors are expected to facilitate these functions. In initial work identifying leader behavior, Fleishman (1953) observed that subordinates perceived their supervisors' behavior in terms of two broad categories referred to as consideration and initiating structure. Consideration includes behavior involved in fostering effective relationships. Examples of such behavior would include showing concern for a subordinate or acting in a supportive manner towards others. Initiating structure involves the actions of the leader focused specifically on task accomplishment. This could include role clarification, setting performance standards, and holding subordinates accountable to those standards.

Integrated psychological theory

The Integrated Psychological theory of leadership is an attempt to integrate the strengths of the older theories (i.e. traits, behavioral/styles, situational and functional) while addressing their limitations, largely by introducing a new element – the need for leaders to develop their leadership presence, attitude toward others and behavioral flexibility by practicing psychological mastery. It also offers a foundation for leaders wanting to apply the philosophies of servant leadership and “authentic leadership”.[39]

Integrated Psychological theory began to attract attention after the publication of James Scouller’s Three Levels of Leadership model (2011).[40] Scouller argued that the older theories offer only limited assistance in developing a person’s ability to lead effectively.[41] He pointed out, for example, that:

- Traits theories, which tend to reinforce the idea that leaders are born not made, might help us select leaders, but they are less useful for developing leaders.

- An ideal style (e.g. Blake & Mouton’s team style) would not suit all circumstances.

- Most of the situational/contingency and functional theories assume that leaders can change their behavior to meet differing circumstances or widen their behavioral range at will, when in practice many find it hard to do so because of unconscious beliefs, fears or ingrained habits. Thus, he argued, leaders need to work on their inner psychology.

- None of the old theories successfully address the challenge of developing “leadership presence”; that certain “something” in leaders that commands attention, inspires people, wins their trust and makes followers want to work with them.

Scouller therefore proposed the Three Levels of Leadership model, which was later categorized as an “Integrated Psychological” theory on the Businessballs education website.[42] In essence, his model summarizes what leaders have to do, not only to bring leadership to their group or organization, but also to develop themselves technically and psychologically as leaders.

The three levels in his model are Public, Private and Personal leadership:

- The first two – public and private leadership – are “outer” or behavioral levels. These are the behaviors that address what Scouller called “the four dimensions of leadership”. These dimensions are: (1) a shared, motivating group purpose; (2) action, progress and results; (3) collective unity or team spirit; (4) individual selection and motivation. Public leadership focuses on the 34 behaviors involved in influencing two or more people simultaneously. Private leadership covers the 14 behaviors needed to influence individuals one to one.

- The third – personal leadership – is an “inner” level and concerns a person’s growth toward greater leadership presence, knowhow and skill. Working on one’s personal leadership has three aspects: (1) Technical knowhow and skill (2) Developing the right attitude toward other people – which is the basis of servant leadership (3) Psychological self-mastery – the foundation for authentic leadership.

Scouller argued that self-mastery is the key to growing one’s leadership presence, building trusting relationships with followers and dissolving one’s limiting beliefs and habits, thereby enabling behavioral flexibility as circumstances change, while staying connected to one’s core values (that is, while remaining authentic). To support leaders’ development, he introduced a new model of the human psyche and outlined the principles and techniques of self-mastery.[43]

Transactional and transformational theories

Eric Berne[44] first analyzed the relations between a group and its leadership in terms of transactional analysis.

The transactional leader (Burns, 1978)[45] is given power to perform certain tasks and reward or punish for the team's performance. It gives the opportunity to the manager to lead the group and the group agrees to follow his lead to accomplish a predetermined goal in exchange for something else. Power is given to the leader to evaluate, correct, and train subordinates when productivity is not up to the desired level, and reward effectiveness when expected outcome is reached. Idiosyncrasy Credits, first posited by Edward Hollander (1971) is one example of a concept closely related to transactional leadership.

Leader–member exchange theory

Another theory that addresses a specific aspect of the leadership process is the leader–member exchange (LMX) theory, which evolved from an earlier theory called the vertical dyad linkage (VDL) model. Both of these models focus on the interaction between leaders and individual followers. Similar to the transactional approach, this interaction is viewed as a fair exchange whereby the leader provides certain benefits such as task guidance, advice, support, and/or significant rewards and the followers reciprocate by giving the leader respect, cooperation, commitment to the task and good performance. However, LMX recognizes that leaders and individual followers will vary in the type of exchange that develops between them.[46] LMX theorizes that the type of exchanges between the leader and specific followers can lead to the creation of in-groups and out-groups. In-group members are said to have high-quality exchanges with the leader, while out-group members have low-quality exchanges with the leader.[47]

In-group members

In-group members are perceived by the leader as being more experienced, competent, and willing to assume responsibility than other followers. The leader begins to rely on these individuals to help with especially challenging tasks. If the follower responds well, the leader rewards him/her with extra coaching, favorable job assignments, and developmental experiences. If the follower shows high commitment and effort followed by additional rewards, both parties develop mutual trust, influence, and support of one another. Research shows the in-group members usually receive higher performance evaluations from the leader, higher satisfaction, and faster promotions than out-group members.[48] In-group members are also likely to build stronger bonds with their leaders by sharing the same social backgrounds and interests.

Out-group members

Out-group members often receive less time and more distant exchanges then their in-group counterparts. With out-group members, leaders expect no more than adequate job performance, good attendance, reasonable respect, and adherence to the job description in exchange for a fair wage and standard benefits. The leader spends less time with out-group members, they have fewer developmental experiences, and the leader tends to emphasize his/her formal authority to obtain compliance to leader requests. Research shows that out-group members are less satisfied with their job and organization, receive lower performance evaluations from the leader, see their leader as less fair, and are more likely to file grievances or leave the organization.[49]

Emotions

Leadership can be perceived as a particularly emotion-laden process, with emotions entwined with the social influence process.[50] In an organization, the leader's mood has some effects on his/her group. These effects can be described in three levels:[51]

- The mood of individual group members. Group members with leaders in a positive mood experience more positive mood than do group members with leaders in a negative mood. The leaders transmit their moods to other group members through the mechanism of emotional contagion.[51] Mood contagion may be one of the psychological mechanisms by which charismatic leaders influence followers.[52]

- The affective tone of the group. Group affective tone represents the consistent or homogeneous affective reactions within a group. Group affective tone is an aggregate of the moods of the individual members of the group and refers to mood at the group level of analysis. Groups with leaders in a positive mood have a more positive affective tone than do groups with leaders in a negative mood.[51]

- Group processes like coordination, effort expenditure, and task strategy. Public expressions of mood impact how group members think and act. When people experience and express mood, they send signals to others. Leaders signal their goals, intentions, and attitudes through their expressions of moods. For example, expressions of positive moods by leaders signal that leaders deem progress toward goals to be good. The group members respond to those signals cognitively and behaviorally in ways that are reflected in the group processes.[51]

In research about client service, it was found that expressions of positive mood by the leader improve the performance of the group, although in other sectors there were other findings.[53]

Beyond the leader's mood, her/his behavior is a source for employee positive and negative emotions at work. The leader creates situations and events that lead to emotional response. Certain leader behaviors displayed during interactions with their employees are the sources of these affective events. Leaders shape workplace affective events. Examples – feedback giving, allocating tasks, resource distribution. Since employee behavior and productivity are directly affected by their emotional states, it is imperative to consider employee emotional responses to organizational leaders.[54] Emotional intelligence, the ability to understand and manage moods and emotions in the self and others, contributes to effective leadership within organizations.[53]

Neo-emergent theory

The neo-emergent leadership theory (from the Oxford school of leadership) espouses that leadership is created through the emergence of information by the leader or other stakeholders, not through the true actions of the leader himself. In other words, the reproduction of information or stories form the basis of the perception of leadership by the majority. It is well known that the great naval hero Lord Nelson often wrote his own versions of battles he was involved in, so that when he arrived home in England he would receive a true hero's welcome.[citation needed] In modern society, the press, blogs and other sources report their own views of a leader, which may be based on reality, but may also be based on a political command, a payment, or an inherent interest of the author, media, or leader. Therefore, it can be contended that the perception of all leaders is created and in fact does not reflect their true leadership qualities at all.

Styles

A leadership style is a leader's style of providing direction, implementing plans, and motivating people. It is the result of the philosophy, personality, and experience of the leader. Rhetoric specialists have also developed models for understanding leadership (Robert Hariman, Political Style,[55] Philippe-Joseph Salazar, L'Hyperpolitique. Technologies politiques De La Domination[56]).

Different situations call for different leadership styles. In an emergency when there is little time to converge on an agreement and where a designated authority has significantly more experience or expertise than the rest of the team, an autocratic leadership style may be most effective; however, in a highly motivated and aligned team with a homogeneous level of expertise, a more democratic or laissez-faire style may be more effective. The style adopted should be the one that most effectively achieves the objectives of the group while balancing the interests of its individual members.[57]

Engaging style

Engaging as part of leadership style has been mentioned in various literature earlier. Dr. Stephen L. Cohen, the Senior Vice President for Right Management’s Leadership Development Center of Excellence, has in his article Four Key Leadership Practices for Leading in Tough Times has mentioned Engagement as the fourth Key practice. He writes, "these initiatives do for the organization is engage both leaders and employees in understanding the existing conditions and how they can collectively assist in addressing them. Reaching out to employees during difficult times to better understand their concerns and interests by openly and honestly conveying the impact of the downturn on them and their organizations can provide a solid foundation for not only engaging them but retaining them when things do turn around.[58]

Engagement as the key to Collaborative Leadership is also emphasized in several original research papers and programs.[59] Becoming an agile has long been associated with Engaging leaders - rather than leadership with an hands off approach.[60]

Autocratic or authoritarian style

Under the autocratic leadership style, all decision-making powers are centralized in the leader, as with dictators.

Leaders do not entertain any suggestions or initiatives from subordinates. The autocratic management has been successful as it provides strong motivation to the manager. It permits quick decision-making, as only one person decides for the whole group and keeps each decision to him/herself until he/she feels it needs to be shared with the rest of the group.[57]

Participative or democratic style

The democratic leadership style consists of the leader sharing the decision-making abilities with group members by promoting the interests of the group members and by practicing social equality. This has also been called shared leadership.

Laissez-faire or free-rein style

A person may be in a leadership position without providing leadership, leaving the group to fend for itself. Subordinates are given a free hand in deciding their own policies and methods. The subordinates are motivated to be creative and innovative.

Narcissistic leadership

Narcissistic leadership is a leadership style in which the leader is only interested in him/herself. Their priority is themselves - at the expense of their people/group members. This leader exhibits the characteristics of a narcissist: arrogance, dominance and hostility. It is a common leadership style. The narcissism may range from anywhere between healthy and destructive. To critics, "narcissistic leadership (preferably destructive) is driven by unyielding arrogance, self-absorption, and a personal egotistic need for power and admiration."[61]

Toxic leadership

A toxic leader is someone who has responsibility over a group of people or an organization, and who abuses the leader–follower relationship by leaving the group or organization in a worse-off condition than when he/she joined it.

Task-oriented and relationship-oriented leadership

Task-oriented leadership is a style in which the leader is focused on the tasks that need to be performed in order to meet a certain production goal. Task-oriented leaders are generally more concerned with producing a step-by-step solution for given problem or goal, strictly making sure these deadlines are met, results and reaching target outcomes.[62]

Relationship-oriented leadership is a contrasting style in which the leader is more focused on the relationships amongst the group and is generally more concerned with the overall well-being and satisfaction of group members.[63] Relationship-oriented leaders emphasize communication within the group, shows trust and confidence in group members, and shows appreciation for work done.

Task-oriented leaders are typically less concerned with the idea of catering to group members, and more concerned with acquiring a certain solution to meet a production goal. For this reason, they typically are able to make sure that deadlines are met, yet their group members' well-being may suffer.[62] Relationship-oriented leaders are focused on developing the team and the relationships in it. The positives to having this kind of environment are that team members are more motivated and have support, however, the emphasis on relations as opposed to getting a job done might make productivity suffer.[62]

Sex differences in leadership behavior

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (February 2013) |

Another factor that covaries with leadership style is whether the person is male or female. When men and women come together in groups, they tend to adopt different leadership styles. Men generally assume an agentic leadership style. They are task-oriented, active, decision focused, independent and goal oriented. Women, on the other hand, are generally more communal when they assume a leadership position; they strive to be helpful towards others, warm in relation to others, understanding, and mindful of others' feelings. In general, when women are asked to describe themselves to others in newly formed groups, they emphasize their open, fair, responsible, and pleasant communal qualities. They give advice, offer assurances, and manage conflicts in an attempt to maintain positive relationships among group members. Women connect more positively to group members by smiling, maintaining eye contact and respond tactfully to others’ comments. Men, conversely, describe themselves as influential, powerful and proficient at the task that needs to be done. They tend to place more focus on initiating structure within the group, setting standards and objectives, identifying roles, defining responsibilities and standard operating procedures, proposing solutions to problems, monitoring compliance with procedures, and finally, emphasizing the need for productivity and efficiency in the work that needs to be done. As leaders, men are primarily task-oriented, but women tend to be both task- and relationship-oriented. However, it is important to note that these sex differences are only tendencies, and do not manifest themselves within men and women across all groups and situations.[64]

Performance

In the past, some researchers have argued that the actual influence of leaders on organizational outcomes is overrated and romanticized as a result of biased attributions about leaders (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1987). Despite these assertions, however, it is largely recognized and accepted by practitioners and researchers that leadership is important, and research supports the notion that leaders do contribute to key organizational outcomes (Day & Lord, 1988; Kaiser, Hogan, & Craig, 2008). To facilitate successful performance it is important to understand and accurately measure leadership performance.

Job performance generally refers to behavior that is expected to contribute to organizational success (Campbell, 1990). Campbell identified a number of specific types of performance dimensions; leadership was one of the dimensions that he identified. There is no consistent, overall definition of leadership performance (Yukl, 2006). Many distinct conceptualizations are often lumped together under the umbrella of leadership performance, including outcomes such as leader effectiveness, leader advancement, and leader emergence (Kaiser et al., 2008). For instance, leadership performance may be used to refer to the career success of the individual leader, performance of the group or organization, or even leader emergence. Each of these measures can be considered conceptually distinct. While these aspects may be related, they are different outcomes and their inclusion should depend on the applied or research focus.

Leadership traits

Most theories in the 20th century argued that great leaders were born, not made. Current studies have indicated that leadership is much more complex and cannot be boiled down to a few key traits of an individual. Years of observation and study have indicated that one such trait or a set of traits does not make an extraordinary leader. What scholars have been able to arrive at is that leadership traits of an individual do not change from situation to situation; such traits include intelligence, assertiveness, or physical attractiveness.[65] However, each key trait may be applied to situations differently, depending on the circumstances. The following summarizes the main leadership traits found in research by Jon P. Howell, business professor at New Mexico State University and author of the book Snapshots of Great Leadership.

Determination and drive include traits such as initiative, energy, assertiveness, perseverance, masculinity, and sometimes dominance. People with these traits often tend to wholeheartedly pursue their goals, work long hours, are ambitious, and often are very competitive with others. Cognitive capacity includes intelligence, analytical and verbal ability, behavioral flexibility, and good judgment. Individuals with these traits are able to formulate solutions to difficult problems, work well under stress or deadlines, adapt to changing situations, and create well-thought-out plans for the future. Howell provides examples of Steve Jobs and Abraham Lincoln as encompassing the traits of determination and drive as well as possessing cognitive capacity, demonstrated by their ability to adapt to their continuously changing environments.[65]

Self-confidence encompasses the traits of high self-esteem, assertiveness, emotional stability, and self-assurance. Individuals that are self-confident do not doubt themselves or their abilities and decisions; they also have the ability to project this self-confidence onto others, building their trust and commitment. Integrity is demonstrated in individuals who are truthful, trustworthy, principled, consistent, dependent, loyal, and not deceptive. Leaders with integrity often share these values with their followers, as this trait is mainly an ethics issue. It is often said that these leaders keep their word and are honest and open with their cohorts. Sociability describes individuals who are friendly, extroverted, tactful, flexible, and interpersonally competent. Such a trait enables leaders to be accepted well by the public, use diplomatic measures to solve issues, as well as hold the ability to adapt their social persona to the situation at hand. According to Howell, Mother Teresa is an exceptional example that embodies integrity, assertiveness, and social abilities in her diplomatic dealings with the leaders of the world.[65]

Few great leaders encompass all of the traits listed above, but many have the ability to apply a number of them to succeed as front-runners of their organization or situation.

The ontological–phenomenological model for leadership

One of the more recent definitions of leadership comes from Werner Erhard, Michael C. Jensen, Steve Zaffron, and Kari Granger who describe leadership as “an exercise in language that results in the realization of a future that wasn’t going to happen anyway, which future fulfills (or contributes to fulfilling) the concerns of the relevant parties…”. This definition ensures that leadership is talking about the future and includes the fundamental concerns of the relevant parties. This differs from relating to the relevant parties as “followers” and calling up an image of a single leader with others following. Rather, a future that fulfills on the fundamental concerns of the relevant parties indicates the future that wasn’t going to happen is not the “idea of the leader”, but rather is what emerges from digging deep to find the underlying concerns of those who are impacted by the leadership.[66]

Contexts

Organizations

An organization that is established as an instrument or means for achieving defined objectives has been referred to as a formal organization. Its design specifies how goals are subdivided and reflected in subdivisions of the organization. Divisions, departments, sections, positions, jobs, and tasks make up this work structure. Thus, the formal organization is expected to behave impersonally in regard to relationships with clients or with its members. According to Weber's definition, entry and subsequent advancement is by merit or seniority. Employees receive a salary and enjoy a degree of tenure that safeguards them from the arbitrary influence of superiors or of powerful clients. The higher one's position in the hierarchy, the greater one's presumed expertise in adjudicating problems that may arise in the course of the work carried out at lower levels of the organization. It is this bureaucratic structure that forms the basis for the appointment of heads or chiefs of administrative subdivisions in the organization and endows them with the authority attached to their position.[67]

In contrast to the appointed head or chief of an administrative unit, a leader emerges within the context of the informal organization that underlies the formal structure. The informal organization expresses the personal objectives and goals of the individual membership. Their objectives and goals may or may not coincide with those of the formal organization. The informal organization represents an extension of the social structures that generally characterize human life — the spontaneous emergence of groups and organizations as ends in themselves.

In prehistoric times, humanity was preoccupied with personal security, maintenance, protection, and survival. Now humanity spends a major portion of waking hours working for organizations. The need to identify with a community that provides security, protection, maintenance, and a feeling of belonging has continued unchanged from prehistoric times. This need is met by the informal organization and its emergent, or unofficial, leaders.[68][69]

Leaders emerge from within the structure of the informal organization. Their personal qualities, the demands of the situation, or a combination of these and other factors attract followers who accept their leadership within one or several overlay structures. Instead of the authority of position held by an appointed head or chief, the emergent leader wields influence or power. Influence is the ability of a person to gain co-operation from others by means of persuasion or control over rewards. Power is a stronger form of influence because it reflects a person's ability to enforce action through the control of a means of punishment.[68]

A leader is a person who influences a group of people towards a specific result. It is not dependent on title or formal authority. (Elevos, paraphrased from Leaders, Bennis, and Leadership Presence, Halpern & Lubar.) Ogbonnia (2007) defines an effective leader "as an individual with the capacity to consistently succeed in a given condition and be viewed as meeting the expectations of an organization or society." Leaders are recognized by their capacity for caring for others, clear communication, and a commitment to persist.[70] An individual who is appointed to a managerial position has the right to command and enforce obedience by virtue of the authority of their position. However, she or he must possess adequate personal attributes to match this authority, because authority is only potentially available to him/her. In the absence of sufficient personal competence, a manager may be confronted by an emergent leader who can challenge her/his role in the organization and reduce it to that of a figurehead. However, only authority of position has the backing of formal sanctions. It follows that whoever wields personal influence and power can legitimize this only by gaining a formal position in the hierarchy, with commensurate authority.[68] Leadership can be defined as one's ability to get others to willingly follow. Every organization needs leaders at every level.[71]

Management

Over the years the philosophical terminology of "management" and "leadership" have, in the organizational context, been used both as synonyms and with clearly differentiated meanings. Debate is fairly common about whether the use of these terms should be restricted, and generally reflects an awareness of the distinction made by Burns (1978) between "transactional" leadership (characterized by e.g. emphasis on procedures, contingent reward, management by exception) and "transformational" leadership (characterized by e.g. charisma, personal relationships, creativity).[45]

Group leadership

In contrast to individual leadership, some organizations have adopted group leadership. In this situation, more than one person provides direction to the group as a whole. Some organizations have taken this approach in hopes of increasing creativity, reducing costs, or downsizing. Others may see the traditional leadership of a boss as costing too much in team performance. In some situations, the team members best able to handle any given phase of the project become the temporary leaders. Additionally, as each team member has the opportunity to experience the elevated level of empowerment, it energizes staff and feeds the cycle of success.[72]

Leaders who demonstrate persistence, tenacity, determination, and synergistic communication skills will bring out the same qualities in their groups. Good leaders use their own inner mentors to energize their team and organizations and lead a team to achieve success.[73]

According to the National School Boards Association (USA):[74]

These Group Leaderships or Leadership Teams have specific characteristics:

Characteristics of a Team

- There must be an awareness of unity on the part of all its members.

- There must be interpersonal relationship. Members must have a chance to contribute, and learn from and work with others.

- The members must have the ability to act together toward a common goal.

Ten characteristics of well-functioning teams:

- Purpose: Members proudly share a sense of why the team exists and are invested in accomplishing its mission and goals.

- Priorities: Members know what needs to be done next, by whom, and by when to achieve team goals.

- Roles: Members know their roles in getting tasks done and when to allow a more skillful member to do a certain task.

- Decisions: Authority and decision-making lines are clearly understood.

- Conflict: Conflict is dealt with openly and is considered important to decision-making and personal growth.

- Personal traits: members feel their unique personalities are appreciated and well utilized.

- Norms: Group norms for working together are set and seen as standards for every one in the groups.

- Effectiveness: Members find team meetings efficient and productive and look forward to this time together.

- Success: Members know clearly when the team has met with success and share in this equally and proudly.

- Training: Opportunities for feedback and updating skills are provided and taken advantage of by team members.

Self-leadership

Self-leadership is a process that occurs within an individual, rather than an external act. It is an expression of who we are as people.[75]

Primates

Mark van Vugt and Anjana Ahuja in Naturally Selected: The Evolutionary Science of Leadership present evidence of leadership in nonhuman animals, from ants and bees to baboons and chimpanzees. They suggest that leadership has a long evolutionary history and that the same mechanisms underpinning leadership in humans can be found in other social species, too.[76] Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, in Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence, present evidence that only humans and chimpanzees, among all the animals living on Earth, share a similar tendency for a cluster of behaviors: violence, territoriality, and competition for uniting behind the one chief male of the land.[77] This position is contentious. Many animals beyond apes are territorial, compete, exhibit violence, and have a social structure controlled by a dominant male (lions, wolves, etc.), suggesting Wrangham and Peterson's evidence is not empirical. However, we must examine other species as well, including elephants (which are matriarchal and follow an alpha female), meerkats (who are likewise matriarchal), and many others.

By comparison, bonobos, the second-closest species-relatives of humans, do not unite behind the chief male of the land. The bonobos show deference to an alpha or top-ranking female that, with the support of her coalition of other females, can prove as strong as the strongest male. Thus, if leadership amounts to getting the greatest number of followers, then among the bonobos, a female almost always exerts the strongest and most effective leadership. However, not all scientists agree on the allegedly peaceful nature of the bonobo or its reputation as a "hippie chimp".[2]

Historical views

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

Sanskrit literature identifies ten types of leaders. Defining characteristics of the ten types of leaders are explained with examples from history and mythology.[78]

Aristocratic thinkers have postulated that leadership depends on one's "blue blood" or genes. Monarchy takes an extreme view of the same idea, and may prop up its assertions against the claims of mere aristocrats by invoking divine sanction (see the divine right of kings). Contrariwise, more democratically-inclined theorists have pointed to examples of meritocratic leaders, such as the Napoleonic marshals profiting from careers open to talent.

In the autocratic/paternalistic strain of thought, traditionalists recall the role of leadership of the Roman pater familias. Feminist thinking, on the other hand, may object to such models as patriarchal and posit against them emotionally-attuned, responsive, and consensual empathetic guidance, which is sometimes associated with matriarchies.

Comparable to the Roman tradition, the views of Confucianism on "right living" relate very much to the ideal of the (male) scholar-leader and his benevolent rule, buttressed by a tradition of filial piety.

Leadership is a matter of intelligence, trustworthiness, humaneness, courage, and discipline . . . Reliance on intelligence alone results in rebelliousness. Exercise of humaneness alone results in weakness. Fixation on trust results in folly. Dependence on the strength of courage results in violence. Excessive discipline and sternness in command result in cruelty. When one has all five virtues together, each appropriate to its function, then one can be a leader. — Sun Tzu[79]

In the 19th century, the elaboration of anarchist thought called the whole concept of leadership into question. (Note that the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word "leadership" in English only as far back as the 19th century.) One response to this denial of élitism came with Leninism, which demanded an élite group of disciplined cadres to act as the vanguard of a socialist revolution, bringing into existence the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Other historical views of leadership have addressed the seeming contrasts between secular and religious leadership. The doctrines of Caesaro-papism have recurred and had their detractors over several centuries. Christian thinking on leadership has often emphasized stewardship of divinely-provided resources—human and material—and their deployment in accordance with a Divine plan. Compare servant leadership.

For a more general take on leadership in politics, compare the concept of the statesperson.

Leadership myths

Leadership, although largely talked about, has been described as one of the least understood concepts across all cultures and civilizations. Over the years, many researchers have stressed the prevalence of this misunderstanding, stating that the existence of several flawed assumptions, or myths, concerning leadership often interferes with individuals’ conception of what leadership is all about (Gardner, 1965; Bennis, 1975).[80][81]

Leadership is innate

According to some, leadership is determined by distinctive dispositional characteristics present at birth (e.g., extraversion; intelligence; ingenuity). However, according to Forsyth (2009) there is evidence to show that leadership also develops through hard work and careful observation.[82] Thus, effective leadership can result from nature (i.e., innate talents) as well as nurture (i.e., acquired skills).

Leadership is possessing power over others

Although leadership is certainly a form of power, it is not demarcated by power over people – rather, it is a power with people that exists as a reciprocal relationship between a leader and his/her followers (Forsyth, 2009).[82] Despite popular belief, the use of manipulation, coercion, and domination to influence others is not a requirement for leadership. In actuality, individuals who seek group consent and strive to act in the best interests of others can also become effective leaders (e.g., class president; court judge).

Leaders are positively influential

The validity of the assertion that groups flourish when guided by effective leaders can be illustrated using several examples. For instance, according to Baumeister et al. (1988), the bystander effect (failure to respond or offer assistance) that tends to develop within groups faced with an emergency is significantly reduced in groups guided by a leader.[83] Moreover, it has been documented that group performance,[84] creativity,[85] and efficiency[86] all tend to climb in businesses with designated managers or CEOs. However, the difference leaders make is not always positive in nature. Leaders sometimes focus on fulfilling their own agendas at the expense of others, including his/her own followers (e.g., Pol Pot; Josef Stalin). Leaders who focus on personal gain by employing stringent and manipulative leadership styles often make a difference, but usually do so through negative means.[87]

Leaders entirely control group outcomes

In Western cultures it is generally assumed that group leaders make all the difference when it comes to group influence and overall goal-attainment. Although common, this romanticized view of leadership (i.e., the tendency to overestimate the degree of control leaders have over their groups and their groups’ outcomes) ignores the existence of many other factors that influence group dynamics.[88] For example, group cohesion, communication patterns among members, individual personality traits, group context, the nature or orientation of the work, as well as behavioral norms and established standards influence group functionality in varying capacities. For this reason, it is unwarranted to assume that all leaders are in complete control of their groups' achievements.

All groups have a designated leader

Despite preconceived notions, not all groups need have a designated leader. Groups that are primarily composed of women,[89][90] are limited in size, are free from stressful decision-making,[91] or only exist for a short period of time (e.g., student work groups; pub quiz/trivia teams) often undergo a diffusion of responsibility, where leadership tasks and roles are shared amongst members (Schmid Mast, 2002; Berdahl & Anderson, 2007; Guastello, 2007).

Group members resist leaders

Although research has indicated that group members’ dependence on group leaders can lead to reduced self-reliance and overall group strength,[82] most people actually prefer to be led than to be without a leader (Berkowitz, 1953).[92] This "need for a leader" becomes especially strong in troubled groups that are experiencing some sort of conflict. Group members tend to be more contented and productive when they have a leader to guide them. Although individuals filling leadership roles can be a direct source of resentment for followers, most people appreciate the contributions that leaders make to their groups and consequently welcome the guidance of a leader (Stewart & Manz, 1995).[93]

Action-oriented environments

One approach to team leadership examines action-oriented environments, where effective functional leadership is required to achieve critical or reactive tasks by small teams deployed into the field. In other words, there is leadership of small groups often created to respond to a situation or critical incident.

In most cases these teams are tasked to operate in remote and changeable environments with limited support or backup (action environments). Leadership of people in these environments requires a different set of skills to that of front line management. These leaders must effectively operate remotely and negotiate the needs of the individual, team, and task within a changeable environment. This has been termed action oriented leadership. Some examples of demonstrations of action oriented leadership include extinguishing a rural fire, locating a missing person, leading a team on an outdoor expedition, or rescuing a person from a potentially hazardous environment.

Titles emphasizing authority

At certain stages in their development, the hierarchies of social ranks implied different degrees or ranks of leadership in society. Thus a knight led fewer men in general than did a duke; a baronet might in theory control less land than an earl. See peerage for a systematization of this hierarchy, and order of precedence for links to various systems.

In the course of the 18th to 20th centuries, several political operators took non-traditional paths to become dominant in their societies. They or their systems often expressed a belief in strong individual leadership, but existing titles and labels ("King", "Emperor", "President", and so on) often seemed inappropriate, insufficient, or downright inaccurate in some circumstances. The formal or informal titles or descriptions they or their subordinates employ express and foster a general veneration for leadership of the inspired and autocratic variety. The definite article when used as part of the title (in languages that use definite articles) emphasizes the existence of a sole "true" leader.

Critical thought

Noam Chomsky[94] and others[95] have brought critical thinking to the very concept of leadership and have provided an analysis that asserts that people abrogate their responsibility to think and will actions for themselves. While the conventional view of leadership is rather satisfying to people who "want to be told what to do", these critics say that one should question why they are being subjected to a will or intellect other than their own if the leader is not a Subject Matter Expert (SME).

The fundamentally anti-democratic nature of the leadership principle is challenged by the introduction of concepts such as autogestion, employeeship, common civic virtue, etc., which stress individual responsibility and/or group authority in the work place and elsewhere by focusing on the skills and attitudes that a person needs in general rather than separating out leadership as the basis of a special class of individuals.

Similarly, various historical calamities are attributed to a misplaced reliance on the principle of leadership.

Varieties of individual power

According to Patrick J. Montana and Bruce H. Charnov, the ability to attain these unique powers is what enables leadership to influence subordinates and peers by controlling organizational resources. The successful leader effectively uses these powers to influence employees, and it is important for leaders to understand the uses of power to strengthen their leadership.

The authors distinguish the following types of organizational power:

- Legitimate Power refers to the different types of professional positions within an organization structure that inherit such power (e.g. Manager, Vice President, Director, Supervisor, etc.). These levels of power correspond to the hierarchical executive levels within the organization itself. The higher positions, such as president of the company, have higher power than the rest of the professional positions in the hierarchical executive levels.

- Reward Power is the power given to managers that attain administrative power over a range of rewards (such as raises and promotions). Employees who work for managers desire the reward from the manager and will be influenced by receiving it as a result of work performance.

- Coercive Power is the manager's ability to punish an employee. Punishment can be mild, such as a suspension, or serious, such as termination.

- Expert Power is attained by the manager due to his or her own talents such as skills, knowledge, abilities, or previous experience. A manager who has this power within the organization may be a very valuable and important manager in the company.

- Charisma Power: a manager who has charisma will have a positive influence on workers, and create the opportunity for interpersonal influence.

- Referent Power is a power that is gained by association. A person who has power by association is often referred to as an assistant or deputy.

- Information Power is gained by a person who has possession of important information at an important time when such information is needed to organizational functioning.[96]

See also

Other types and theories

Contexts

Related articles

References

- Notes

- ^ Chemers M. (1997) An integrative theory of leadership. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8058-2679-1

- ^ Locke et al. 1991

- ^ (Richards & Engle, 1986, p.206)

- ^ http://qualities-of-a-leader.com/trait-approach/

- ^ Bird, C. (1940). Social Psychology. New York: Appleton-Century.

- ^ Stogdill, R.M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership: A survey of the literature. Journal of Psychology, 25, 35-71.

- ^ Mann, R.D. (1959). A review of the relationship between personality and performance in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 241-270.

- ^ a b Kenny, D.A. & Zaccaro, S.J. (1983). An estimate of variance due to traits in leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 678-685.

- ^ a b c Lord, R.G., De Vader, C.L., & Alliger, G.M. (1986). A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leader perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 402-410.

- ^ Arvey, R.D., Rotundo, M., Johnson, W., Zhang, Z., & McGue, M. (2006). The determinants of leadership role occupancy: Genetic and personality factors. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 1-20.

- ^ a b Judge, T.A., Bono, J.E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M.W. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 765-780.

- ^ Tagger, S., Hackett, R., Saha, S. (1999). Leadership emergence in autonomous work teams: Antecedents and outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 52, 899-926. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00184.x/abstract

- ^ Kickul, J., & Neuman, G. (2000). Emergence leadership behaviors: The function of personality and cognitive ability in determining teamwork performance and KSAs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15, 27-51.

- ^ Smith, J.A., & Foti, R.J. (1998). A pattern approach to the study of leader emergence. The Leadership Quarterly, 9, 147-160.

- ^ a b Foti, R.J., & Hauenstein, N.M.A. (2007). Pattern and variable approaches in leadership emergence and effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 347-355.

- ^ a b Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62, 6-16.

- ^ Zaccaro, S. J., Gulick, L.M.V. & Khare, V.P. (2008). Personality and leadership. In C. J. Hoyt, G. R. Goethals & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Leadership at the crossroads (Vol 1) (pp. 13-29). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- ^ Gershenoff, A. G., & Foti, R. J. (2003). Leader emergence and gender roles in all-female groups: A contextual examination. Small Group Research, 34, 170-196.

- ^ a b Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world solving complex social problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 11, 11-35.

- ^ Smith, J.A., & Foti R.J. (1998). A pattern approach to the study of leader emergence, Leadership Quarterly, 9, 147-160.

- ^ Magnusson, D. (1995). Holistic interactionism: A perspective for research on personality development. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 219-247). New York: Guilford Press.

- ^ Spillane (2004)

- ^ Horton, Thomas. New York The CEO Paradox (1992)

- ^ Lewin et al. (1939)

- ^ Blake et al. (1964)

- ^ Miltenberger, R.G., (2004). Behavior Modification Principles and Procedures (3rd ed). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- ^ Lussier, R.N., & Achua, C.F., (2010). Leadership, Theory, Application, & Skill Development.(4th ed). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- ^ Spencer (1884), apud Heifetz (1994), pp. 16

- ^ Hemphill (1949)

- ^ Wormer et al. (2007), pp: 198

- ^ Fiedler (1967)

- ^ Vroom, Yetton (1973)

- ^ Vroom, Jago (1988)

- ^ Sternberg, Vroom (2002)

- ^ Lorsch (1974)

- ^ House (1971)

- ^ House (1996)

- ^ Hersey et al. (2008)

- ^ Businessballs management information website – Leadership Theories page, “Integrated Psychological Approach” section: http://www.businessballs.com/leadership-theories.htm#integrated-psychological-leadership

- ^ Scouller, J. (2011). The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill. Cirencester: Management Books 2000., ISBN 9781852526818

- ^ Scouller, J. (2011), pp. 34-35.

- ^ Businessballs information website: Leadership Theories Page, Integrated Psychological Approach section. Businessballs.com.: http://www.businessballs.com/leadership-theories.htm#integrated-psychological-leadership2012-02-24. Retrieved 2012-08-15

- ^ Scouller, J. (2011), pp. 137-237.

- ^ The Structure and Dynamics of Organizations and Groups, Eric Berne, ISBN 0-345-28473-9

- ^ a b Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper and Row Publishers Inc.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ name="Howell, Jon P.">Howell, Jon P. (2012). Snapshots of Great Leadership. London, GBR: Taylor and Francis. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780203103210.

- ^ name="Howell, Jon P.">Howell, Jon P. (2012). Snapshots of Great Leadership. London, GBR: Taylor and Francis. p. 17. ISBN 9780203103210.

- ^ name="Howell, Jon P.">Howell, Jon P. (2012). Snapshots of Great Leadership. London, GBR: Taylor and Francis. p. 17. ISBN 9780203103210.

- ^ name="Howell, Jon P.">Howell, Jon P. (2012). Snapshots of Great Leadership. London, GBR: Taylor and Francis. p. 17. ISBN 9780203103210.

- ^ George J.M. 2000. Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence, Human Relations 53 (2000), pp. 1027–1055

- ^ a b c d Sy, T.; Cote, S.; Saavedra, R. (2005). "The contagious leader: Impact of the leader's mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 90 (2): 295–305. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295. PMID 15769239.

- ^ Bono J.E. & Ilies R. 2006 Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. The Leadership Quarterly 17(4): pp. 317-334

- ^ a b George J.M. 2006. Leader Positive Mood and Group Performance: The Case of Customer Service. Journal of Applied Social Psychology :25(9) pp. 778 - 794

- ^ Dasborough M.T. 2006.Cognitive asymmetry in employee emotional reactions to leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 17(2):pp. 163-178

- ^ Robert Hariman, Political Style, U of Chicago Press, 1995

- ^ Philippe-Joseph Salazar, L'Hyperpolitique. Technologies politiques De La Domination, Paris, 2009

- ^ a b Lewin, K.; Lippitt, R.; White, R.K. (1939). "Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates". Journal of Social Psychology. 10: 271–301.

- ^ http://www.linkageinc.com/thinking/linkageleader/Documents/Stephen_Cohen_Four_Key_Leadership_Practices.pdf

- ^ http://www.collaborativeleadership.org/pages/modules_description.html

- ^ http://www.lominger.com/agileleader/

- ^ Linda L. Neider/Chester A. Schriesheim, The Dark Side of Management (2010) p. 29

- ^ a b c Manktelow, James. "Leadership Style". Mind Tools. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Griffin, Ronald J. Ebert, Ricky W. (2010). Business essentials (8th ed. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-13-705349-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group dynamics. New York: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0495599524.

- ^ a b c Howell, Jon P. (2012). Snapshots of Great Leadership. London, GBR: Taylor and Francis. pp. 4–6. ISBN 9780203103210. Cite error: The named reference "Howell, Jon P." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Forthcoming in "The Handbook for Teaching Leadership," by Werner Erhard, Michael, C. Jensen, & Kari Granger; Scott Snook, Nitin Nohria, Rakesh Khurana (Editors) http://ssrn.com/abstract=1681682

- ^ Cecil A Gibb (1970). Leadership (Handbook of Social Psychology). Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. pp. 884–89. ISBN 0-14-080517-6 9780140805178. OCLC 174777513.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b c Henry P. Knowles; Borje O. Saxberg (1971). Personality and Leadership Behavior. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. pp. 884–89. ISBN 0-14-080517-6 9780140805178. OCLC 118832.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Vugt, M., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. (2008). Leadership, followership, and evolution: Some lessons from the past. American Psychologist, 63, 182-196.[1]

- ^ Hoyle, John R. Leadership and Futuring: Making Visions Happen. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc., 1995.

- ^ The Top 10 Leadership Qualities - HR World

- ^ Ingrid Bens (2006). Facilitating to Lead. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-7879-7731-4.

- ^ Dr. Bart Barthelemy (1997). The Sky Is Not The Limit - Breakthrough Leadership. St. Lucie Press.

- ^ National School Boards Association

- ^ Hackman, M. & Johnson, C. (2009). Leadership: A communication perspective. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

- ^ van Vugt, M., & Ahuja, A.(2010). Naturally Selected: the Evolutionary Science of Leadrship. Harper Collins.

- ^ Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson (1996). Demonic Males. Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. Mariner Books

- ^ KSEEB. Sanskrit Text Book -9th Grade. Government of Karnataka, India.

- ^ THE 100 GREATEST LEADERSHIP PRINCIPLES OF ALL TIME, EDITED BY LESLIE POCKELL WITH ADRIENNE AVILA, 2007, Warner Books

- ^ Gardner, J.W. (1965). Self-Renewal: The Individual and the Innovative Society. New York: Harper and Row.

- ^ Bennis, W. G. (1975). Where have all the leaders gone? Washington, DC: Federal Executive Institute.

- ^ a b c Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group dynamics (5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- ^ Baumeister, R. F., Senders, P. S., Chesner, S. C., & Tice, D. M. (1988). Who’s in charge here? Group leaders do lend help in emergencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 17-22.

- ^ Jung, D., Wu, A., & Chow, C.W. (2008). Towards understanding the direct and indirect effects of CEOs transformational leadership on firm innovation. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 582-594.

- ^ Zaccaro, S.J., & Banks, D.J. (2001). Leadership, vision, and organizational effectiveness. In S. J. Zaccaro and R. J. Klimoski (Editors), The Nature of Organizational Leadership: Understanding the Performance Imperatives Confronting Today’s Leaders. Sand Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Larson, J. R., Jr., Christensen, C., Abbot, A. S., & Franz, T. M. (1996). Diagnosing groups: Charting the flow of information in medical decision-making teams. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 315–330.

- ^ Lipman-Blumen, J. (2005) The Allure of Toxic Leaders. New York: Oxford. University Press Inc.

- ^ Meindl, J.R., Ehrlich, S.B., & Dukerich, J.M. (1985). The romance of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30, 78-102

- ^ Schmid Mast, M. (2002). Female dominance hierarchies: Are they any different from males'? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 29-39.

- ^ Berdahl, J. L., & Anderson, C. (2005). Men, women, and leadership centralization in groups over time. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9, 45-57.

- ^ Guastello, S. J. (2007). Nonlinear dynamics and leadership emergence. Leadership Quarterly, 18, 357–369.

- ^ Berkowitz, L. (1953). Sharing leadership in small, decision-making groups. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 48, 231-238.

- ^ Stewart, G. L., & Manz, C. C. (1995). Leadership for self-managing work teams: A typology and integrative model. Human Relations, 48, 747 – 770.

- ^ Profit over People: neoliberalism and global order, N. Chomsky, 1999 Ch. Consent without Consent, p. 53

- ^ The Relationship between Servant Leadership, Follower Trust, Team Commitment and Unit Effectiveness], Zani Dannhauser, Doctoral Thesis, Stellenbosch University 2007

- ^ Management, P. J. Montana and B. H. Charnov, 2008 Ch. "Leadership: Theory and Practice", p. 253

- Books

- Blake, R.; Mouton, J. (1964). The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston: Gulf Publishing Co.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1841). On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 1-4069-4419-X.

- Fiedler, Fred E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. McGraw-Hill: Harper and Row Publishers Inc.

- Heifetz, Ronald (1994). Leadership without Easy Answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-51858-6.

- Hemphill, John K. (1949). Situational Factors in Leadership. Columbus: Ohio State University Bureau of Educational Research.

- Hersey, Paul; Blanchard, Ken; Johnson, D. (2008). Management of Organizational Behavior: Leading Human Resources (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-13-017598-6.

- Miner, J. B. (2005). Organizational Behavior: Behavior 1: Essential Theories of Motivation and Leadership. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

- Spencer, Herbert (1841). The Study of Sociology. New York: D. A. Appleton. ISBN 0-314-71117-1.

- Tittemore, James A. (2003). Leadership at all Levels. Canada: Boskwa Publishing. ISBN 0-9732914-0-0.

- Vroom, Victor H.; Yetton, Phillip W. (1973). Leadership and Decision-Making. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-3266-0.

- Vroom, Victor H.; Jago, Arthur G. (1988). The New Leadership: Managing Participation in Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-615030-6.

- Van Wormer, Katherine S.; Besthorn, Fred H.; Keefe, Thomas (2007). Human Behavior and the Social Environment: Macro Level: Groups, Communities, and Organizations. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518754-7.

- Montana, Patrick J.; Bruce H. (2008). Management. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series, Inc. ISBN 0-944740-04-9.

- Journal articles

- House, Robert J. (1971). "A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness". Administrative Science Quarterly. 16 (3). Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University: 321–339. doi:10.2307/2391905. JSTOR 2391905.

- House, Robert J. (1996). "Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory". Leadership Quarterly. 7 (3): 323–352. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90024-7.

- Lewin, Kurt; Lippitt, Ronald; White, Ralph (1939). "Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates". Journal of Social Psychology: 271–301.

- http://sbuweb.tcu.edu/jmathis/Org_Mgmt_Materials/Leadership%20-%20Do%20Traits%20Matgter.pdf Kirkpatrick, S.A., (1991). "Leadership: Do traits matter?". Academy of Management Executive. 5 (2).

{{cite journal}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lorsch, Jay W. (Spring 1974). "Review of Leadership and Decision Making". Sloan Management Review.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Spillane, James P.; Diamond, John; et al. (2004). "Towards a theory of leadership practice". Journal of Curriculum Studies. 36 (1): 3–34. doi:10.1080/0022027032000106726.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - Vroom, Victor; Sternberg, Robert J. (2002). "Theoretical Letters: The person versus the situation in leadership". The Leadership Quarterly. 13 (3): 301–323. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00101-7.

Further reading

- Adair, J. (1988). Effective Leadership. London. Pan Books. ISBN 978-0330504195

- Antonakis, John, Cianciolo, Anna T., & Sternberg, Robert J. (2004). The Nature of Leadership, Sage Publications, Inc.

- Argyris, C. (1976) Increasing Leadership Effectiveness, Wiley, New York, 1976 (even though published in 1976, this still remains a "standard" reference text)

- Avolio, B. J., Sosik, J. J., Jung, D. I., & Berson, Y. (2003). Leadership models, methods, and applications. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen & R. J. *Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 12. (pp. 277–307): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F., & Weber, T. J. (in press). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology.

- Bass, B.M. & Avolio, B.J. (1995). MLQ Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire for Research: Permission Set. Redwood City, CA: Mindgarden.

- Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill's handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York, NY, US: Free Press.

- Bennis, W. (1989) On Becoming a Leader, Addison Wesley, New York, 1989

- Borman, W. C., & Brush, D. H. (1993). More progress toward a taxonomy of managerial performance requirements. Human Performance, 6(1), 1-21.

- Bray, D. W., Campbell, R. J., & Grant, D. L. (1974). Formative years in business: a long-term AT&T study of managerial lives: Wiley, New York.