Cluster headache: Difference between revisions

Reverting to last version by 51505150VH. The phrase "suicide headaches" has sat in this article unreferenced since 13 August 2004. It should have been taken out or given a citation a long, long time ago. |

Undid revision 588826996 by Scott Martin (talk) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''cluster headache''' is a [[Neurological disorder|neurological disease]] that involves, as its most prominent feature, an immense degree of [[Headache|pain in the head]]. Patients typically experience repeated attacks of excruciatingly severe unilateral headache pain.<ref>http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref><ref>http://www.adelaide.edu.au/painresearch/headache/headache_cluster/{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref> Cluster headache belongs to a group of primary headache disorders, classified as "Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias" or (TACs). There is currently no known cause, or cure for a cluster headache. |

The '''cluster headache''', nicknamed the "'''suicide headache'''",{{citation needed|date=December 2013}} is a [[Neurological disorder|neurological disease]] that involves, as its most prominent feature, an immense degree of [[Headache|pain in the head]]. Patients typically experience repeated attacks of excruciatingly severe unilateral headache pain.<ref>http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref><ref>http://www.adelaide.edu.au/painresearch/headache/headache_cluster/{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref> Cluster headache belongs to a group of primary headache disorders, classified as "Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias" or (TACs). There is currently no known cause, or cure for a cluster headache. |

||

Cluster headache attacks often occur periodically; spontaneous remissions may interrupt active periods of pain, though about 10-15% of chronic cluster headache sufferers never remit.<ref name="ihs-classification.org">http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref> The condition affects approximately 0.1% of the population and men are more commonly affected than women, by a ratio of 2.1:1.<ref name=pmid15742909>{{cite journal |url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0215/p717.html |title=Management of Cluster Headache |date=February 15, 2005 |journal=American Family Physician |pmid=15742909 |first1=Ellen |last1=Beck |first2=William J. |last2=Sieber |first3=Raúl |last3=Trejo |volume=71 |issue=4 |pages=717–24}}</ref> |

Cluster headache attacks often occur periodically; spontaneous remissions may interrupt active periods of pain, though about 10-15% of chronic cluster headache sufferers never remit.<ref name="ihs-classification.org">http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html{{full|date=September 2013}}</ref> The condition affects approximately 0.1% of the population and men are more commonly affected than women, by a ratio of 2.1:1.<ref name=pmid15742909>{{cite journal |url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0215/p717.html |title=Management of Cluster Headache |date=February 15, 2005 |journal=American Family Physician |pmid=15742909 |first1=Ellen |last1=Beck |first2=William J. |last2=Sieber |first3=Raúl |last3=Trejo |volume=71 |issue=4 |pages=717–24}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:48, 2 January 2014

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: excessive use of dated, experimental or primary sources, with conflicting advice. (October 2013) |

| Cluster headache | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 0.1% |

The cluster headache, nicknamed the "suicide headache",[citation needed] is a neurological disease that involves, as its most prominent feature, an immense degree of pain in the head. Patients typically experience repeated attacks of excruciatingly severe unilateral headache pain.[1][2] Cluster headache belongs to a group of primary headache disorders, classified as "Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias" or (TACs). There is currently no known cause, or cure for a cluster headache.

Cluster headache attacks often occur periodically; spontaneous remissions may interrupt active periods of pain, though about 10-15% of chronic cluster headache sufferers never remit.[3] The condition affects approximately 0.1% of the population and men are more commonly affected than women, by a ratio of 2.1:1.[4]

The pain of a cluster headache has been described as the most extreme pain a human can possibly endure.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Cluster headaches are recurring bouts of excruciating unilateral headache attacks [4] of extreme intensity.[6] The duration of typical cluster headache attack ranges from about 15 – 180 minutes. The onset of an attack is rapid and most often without preliminary signs that are characteristic in migraine. Some sufferers report preliminary sensations of pain in the general area of attack, often referred to by patients as "shadows", that may warn them an attack is lurking or imminent, or these symptoms may linger after an attack has passed, or even between attacks.[7] Though a cluster headache is strictly unilateral, there are some documented cases of "side-shift" between cluster periods, extremely rare, simultaneously (within the same cluster period) bilateral headache.[8]

Pain

The pain of cluster headaches is remarkably greater than in other headache conditions, including severe migraine. The term "headache" does not adequately convey the severity of the condition; experts have suggested that the disease may be the most painful condition known to medical science. Female patients have reported cluster headache pain as being more severe than pain of natural childbirth.[9] Peter Goadsby, a neurologist and headache specialist at the Kings College Hospital, has commented:

"Cluster headache is probably the worst pain that humans experience. I know that's quite a strong remark to make, but if you ask a cluster headache patient if they've had a worse experience, they'll universally say they haven't. ... Women with cluster headache will tell you that an attack is worse than giving birth. So you can imagine that these people give birth without anaesthetic once or twice a day, for six, eight or ten weeks at a time, and then have a break."[10]

The pain is lancinating or boring/drilling in quality and is located behind the eye (periorbital) or in the temple, sometimes radiating to the jaw. Analogies frequently used to describe the pain are a red-hot poker inserted into the eye, or a spike penetrating from the top of the head, behind one eye, radiating down to the base of the brain. Some patients compare the location and quality of pain intensity with ice-cream headache,[11] with similar speed of onset of attack, but instead with regular recurrence and longer duration of up to 3 hours per attack. The condition was originally named Horton's Cephalalgia after Dr. B.T Horton, who postulated the first theory as to their pathogenesis. His original paper describes the severity of the headaches as being able to take normal men and force them to attempt or complete suicide. From Horton's 1939 paper on cluster headache:

"Our patients were disabled by the disorder and suffered from bouts of pain from two to twenty times a week. They had found no relief from the usual methods of treatment. Their pain was so severe that several of them had to be constantly watched for fear of suicide. Most of them were willing to submit to any operation which might bring relief."[12]

Other symptoms

The typical symptoms of cluster headache are grouping (cluster) of recurring headache attacks of severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain lasting 15–180 minutes. If left untreated, attack frequency will range from one to 8 attacks every 24 hours.[3] The headache attack is accompanied by at least one of the following autonomic symptoms: ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (pupil constriction) conjunctival injection (redness of the conjunctiva), lacrimation (tearing), rhinorrhea (runny nose), and, less commonly, facial blushing, swelling, or sweating, commonly but not always appearing on the same side of the head as the pain.[13]

During a cluster attack a patient may experience restlessness, the sufferer often pacing the room or rocking back and forth. The sufferer may also report photosensitivity, or display an aversion to light (Photophobia) and/or sensitivity to noise (phonophobia) during the attack. Nausea rarely accompanies a cluster headache, though it has been reported.[4] In some patients the neck may feel stiff or tender in the aftermath of a headache, with jaw or tooth pain sometimes present. Sufferers sometimes report feeling as though their nose is blocked and that they are unable to breathe out of one of their nostrils.

Secondary effects can include, but are not limited to; inability to organize thoughts and plans, physical exhaustion, confusion, agitation, aggressiveness, depression and anxiety.

Patients tend to dread facing another headache and may adjust their physical or social activities or sometimes seek assistance to accomplish seemingly normal tasks. Patients may hesitate to schedule plans in reaction to the clock-like regularity, or conversely, the unpredictability of the pain schedule. These factors can lead patients to experience generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorder,[14] serious depressive disorders,[15] social withdrawal and isolation.[16]

Recurrence

Cluster headaches are occasionally referred to as "alarm clock headaches" because of their ability to wake patients from sleep and because of the regularity of their timing: both the individual attacks and the cluster grouping themselves can have a metronomic regularity; attacks striking at a precise time of day each morning or night is typical. In some patients the grouping of headache clusters can occur more often around solstices, or spring and autumn equinoxes, sometimes showing circannual periodicity. This has prompted researchers to speculate involvement, or dysfunction of the brain's Hypothalamus, which controls the body's "biological clock" and circadian rhythm.[17][18] Conversely, some patients' attack frequency may be highly unpredictable, showing no predictable periodicity at all.

In episodic cluster headaches, these attacks occur once or more daily, often at the same times each day, for a period of several weeks, followed by a headache-free period lasting weeks, months, or years. Approximately 10–15% of cluster headache sufferers are chronic; they can experience multiple headaches every day for years, sometimes without any remission.

In accordance with the International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria, Cluster headaches occurring in two or more cluster periods, lasting from 7 to 365 days with a pain-free remission of one month or longer between the clusters may be classified as episodic. If attacks occur for more than a year without pain-free remission of at least one month, the condition is classified chronic.[19] Chronic cluster headaches occur continuously without any "remission" periods between cycles. Chronic sufferers may have "high" and "low" variation in cycles, meaning the frequency and severity of attacks may change without predictability, for a period of time. The amount of change during these cycles varies between individuals and does not demonstrate complete remission seen in sufferers of the episodic form of cluster headache. The condition may change unpredictably, from chronic to episodic and from episodic to chronic.[20] Remission periods lasting for decades before the resumption of clusters have been known to occur.

Prevalence

While migraines are diagnosed more often in women than men, cluster headaches are more prevalent in men. The male-to-female ratio in cluster headache diagnoses ranges from 4:1 to 10:1. Although cluster headache can occur at any age, the disease primarily emerges between the ages of 20 to 50 years.[21] This gap between the sexes has narrowed over the past few decades and it is not clear whether cluster headaches are becoming more frequent in women, or whether they are being more frequently reported, or perhaps diagnosed more effectively. Limited epidemiological studies have suggested prevalence rates of between 56 and 326 people per 100,000.[22]

Dr Robert Shapiro, a Professor of Neurology and Headache specialist at the University Health Center, University of Georgia states that cluster headache; "has a population prevalence that’s approximately the same as multiple sclerosis. It has a disability level that’s probably pretty approximate to multiple sclerosis.”

Dr Shapiro has said that over the past decade, the NIH has spent $1.872 billion on research into multiple sclerosis, which he states is warranted. Less than $2 million has gone to cluster headache research over the last 25 years.[23]

Pathophysiology

Cluster headache has been historically classified as vascular headaches, as were Migraine headaches. For decades, it has been proposed that intense pain was caused by dilation of blood vessels which was thought to create pressure on the trigeminal nerve. While this theory was thought to be the immediate cause of the pain, the etiology (underlying cause or causes) is not yet fully understood and cluster headache pathogenesis still remains the subject of ongoing research and debate.[24] As more research is conducted, recent investigations into vascular theory of headache disorders are helping to identify and include the role of other possible causative mechanisms in the pain of cluster headache.[25]

Diagnosis

Cluster headache is a primary headache condition in its own right, with no known cause. Cluster headaches are often left misdiagnosed, mismanaged, or undiagnosed for many years, often being confused with migraine, "cluster-like" headache (or mimics), cluster headache subtypes, other Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs) or sometimes other types of primary or secondary headache syndrome.[26] If symptoms of a "cluster-like" headache exist, secondary to a primary attributable cause like aneurysm, tumor or arachnoid cyst[27] (Anatomical, physiological, organic causes etc.), then "cluster-like" pain may be experienced and classified as secondary to the known, identified cause. Cluster-like head pain may be diagnosed as secondary headache and therefore, not cluster headache.[28]

A headache diary [29] can be useful in tracking when and where the pain occurs, how severe it is, how long the pain lasts. A record of coping strategies used will also help both patient and physician distinguish between headache type. Collected data from the patient on frequency, severity and duration of headache attacks is a necessary tool for initial and correct differential diagnosis in headache conditions. Headache researchers, Jensen R, Tfelt-Hansen P. say of cluster headache diagnosis - "The most important question in diagnosing cluster headache is the duration (usually 15 to 180 min) of the extremely severe headache".[30] A detailed oral patient history is required for correct differential diagnosis, as there are no current confirmatory tests for cluster headache.

Correct diagnosis of cluster headache continues to be a challenge for practitioners. This is especially problematic for patients attending Hospital Emergency Departments, where staff are not trained in the diagnosis of rare or complex chronic disease, like cluster headache.[31]

Patients with cluster headache typically experience a lengthy delay to correct diagnosis.[32][33] Patients are often misdiagnosed due to reported neck, tooth, jaw, and sinus symptoms and may unnecessarily endure many years of referral to Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) specialists for investigation of sinuses, Dentists for tooth assessment, Chiropractors and manipulative therapists for treatment, Psychiatrists, Psychologists and many other medical disciplines, before their headache symptoms may be correctly diagnosed.[34]

As a detailed oral history of patient symptoms is the only available data to achieve correct differential diagnosis in headache conditions, many patients endure many years of disease before a correct differential diagnosis is made and treatment for cluster headache specifically sought. Together with misdiagnosis, diagnostic delay in cluster headache is both a major problem and cause of adverse outcomes for patients suffering under the severe duress of chronic cluster headache.[35] Figures on time to correct diagnosis vary, still averaging many years to reach correct differential diagnosis.[36]

Cluster headaches are a benign primary headache syndrome. Because of the relative rareness of the condition and ambiguity of the symptoms, sufferers should not expect immediate diagnosis or treatment in the emergency room (ER). Cluster headache attack itself is not life-threatening.[37] Although experienced ER staff can be sometimes be trained to detect headache types,[38] ER staff training and resources are typically dedicated to managing acute trauma and life-threatening patient presentations.

Rare and intractable headache subtypes, like suspected presentations of cluster headache should be referred to an experienced specialist Neurologist and/or Headache Specialist, with expertise in diagnosis and management of Headache conditions. Dr. Fayyaz Ahmed, Consultant Neurologist, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust says, of differentiating and managing common headache disorder subtypes; "Undergraduates receive very little training on headache disorders even in their placement within the neurosciences. It is, therefore, unlikely that a medical graduate would be expected to make an accurate diagnosis on headache disorders".[39]

Differential

There are other types of headache that are sometimes mistaken for, or may mimic closely, the symptoms reported in cluster headaches.

At initial presentation, the importance of correctly differentiating between headache types cannot be understated. A diligent and knowledgeable practitioner should easily be able to recognize patient reported symptoms of cluster headache,[40] though frequently, cases are incorrectly diagnosed. Incorrect terms like "cluster migraine" only confuse headache types for both practitioner and patient, confound patient's attempts in seeking differential diagnosis and are often the cause of lengthy, unnecessary diagnostic delay,[41] ultimately delaying appropriate specialist treatment.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH) is another unilateral headache condition, without Male predominance usually seen in cluster headache. Paroxysmal Hemicrania may also be episodic. Symptoms of Paroxysmal Hemicrania may be easily mistaken for, or misdiagnosed as cluster headache. CPH typically responds "absolutely" to treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin [42] where in most cases cluster headache typically will show no positive Indomethacin response, making "Indomethacin response" an important diagnostic tool for specialist practitioners seeking correct differential diagnosis between the two separate headache conditions. Attack profile associated with Paroxysmal Hemicrania may be generally of shorter duration, often lasting from 2–30 minutes, but may occur more or less frequently than Cluster Headache attacks.

- SUNCT - "Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache with Conjunctival injection and Tearing" is another headache syndrome belonging to the group of Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgis (TACs)[43] that may also be confused with or misdiagnosed as cluster headache.[44] SUNCT is sometimes seen in patients with Trigeminal Neuralgia[45]

- Trigeminal Neuralgia is a unilateral headache syndrome that may be confused with, or misdiagnosed as cluster headache[46] or "cluster-like" headache, also seen as an overlap condition in SUNCT patients. Overlap in diagnostic features of these different headache conditions can often lead to misdiagnosis.[47]

Prevention

Preventive treatments are used to attempt to provide the sufferer with a long-term reduction or the possibility of elimination of cluster headache attacks. These techniques are generally used in combination with abortive and transitional techniques in order to obtain the best therapeutic results.[48][49] A wide variety of prophylactic medicines are in use, and patient response to these is highly variable.

The calcium channel blocker Verapamil is a first-line recommended preventative therapy.[48][49] Dosages of 360–480 mg daily have been found effective in reducing cluster headache attack frequency.[48] Despite its success in randomized controlled trial, only 4 percent of patients with cluster headache report verapamil use.[48] Current European guidelines suggest the use of the drug at a dose of at least 240 mg daily.[50] Off-label use of high dose Verapamil in cluster headache patients should be routinely ECG/EKG monitored and is strongly recommended.[51] [non-primary source needed]

Steroids, such as prednisolone and dexamethasone may also be effective, and are typically effective within 24–48 hours.[49] This transitional therapy is generally discontinued after 8–10 days of treatment, as preventative treatments become more effective within the body, and as long-term use can result in very severe side effects.[49] Typical dosages are between 50–80 mg daily and then tapered down over the course of 10–12 days.[48]

Methysergide, lithium and the anticonvulsant topiramate are recommended as alternative treatments.[50] Additionally, magnesium supplements have been shown to be of some benefit in about 40% of patients who have low serum levels of magnesium.[52]

Cluster headache specifically, may be triggered by nitrates, nitric oxide producing substances [53] and some alcohol. Glyceryl trinitrate tablets used in the treatment of heart disease may be used in a clinical environment to trigger cluster attack.[54][55]

Psilocybin and LSD

Psilocybin is the psychoactive substance found naturally in hallucinogenic mushrooms. A self-reported interview of 53 cluster headache sufferers taking LSD or Psilocybin was conducted by doctors R. Andrew Sewell, John H. Halpern and Harrison G. Pope, Jr. [citation needed] According to responses, consuming a sub-hallucinogenic dose during and prior to the onset of a cluster episode can abort or prevent the progression. One notable finding is that some patients reported that treatment with Psilocybin or LSD extends remission periods. According to the interview report, "Twenty-two of 26 psilocybin users reported that psilocybin aborted attacks ... 7 of 8 LSD users reported cluster period termination; 18 of 19 psilocybin users and 4 of 5 LSD users reported remission period extension." [citation needed]

In most countries, as in the United States, it is illegal to possess or consume these substances. Hallucinogenic mushrooms and LSD are currently scheduled and controlled substances, and thus medical research has been difficult. [citation needed] In April 2013, a major study by the British government on Psilocybin's benefit in treating depression was postponed because of regulatory and legal concerns.[citation needed] There is growing supporting evidence from the small Cluster Headache community that treatment with these substances is safe and allows them to return to a normal and functional life. [citation needed] For a small population of sufferers, the legal and safety risks are outweighed by the pain caused by the condition. However, in the absence of ongoing safety studies and adverse event monitoring, the safety profile for these substances is largely anecdotal.

National Geographic ran a segment regarding this treatment in their "Drugs Inc 2: Hallucinogens". Season 2. One of many volunteers that were interviewed for the segment was "Dan". Chronicled was his preparation and consumption of psilocybin as well as his pain free period immediately after his maintenance dose.[56] Some sufferers claim that this treatment prevented their suicide. [citation needed] Even the US government's Partnership for a Drug-Free America has noted that, "No other medication, to our knowledge, has been reported to terminate a cluster period." [citation needed]

Psilocybin and LSD are not currently indicated for use by medical practitioners in the management or treatment of Cluster Headache. Psilocybin and LSD have not yet been rigorously clinically validated for safety or efficacy and approved in treating or managing Cluster Headache. There are not yet any clinically recognised risk analyses, dosage schedules, protocols or usage guidelines for Psilocybin or LSD for patients attempting to treat their Cluster headache conditions. There are no official patient information resources available on drug side-effect profile, contraindications, co-morbid conditions and drug interactions.

Risk versus benefit analyses cannot be made and advice given by primary care physicians when consulted on the use of Psilocybin and LSD in cluster headache. Psilocybin and LSD are not currently dispensed to patients through either drug approvals boards, medical ethics committees, or prescribing medical professionals in a clinical setting for the management of Cluster Headache. Cluster Headache patients who may decide to use Psilocybin and LSD, self initiate treatment (self medicate) at their own risk, in the absence of any medical approval or safety monitoring by a primary care physician.

Management

Cluster headache treatments are available that may assist a person who has cluster headaches. While effective treatments for cluster headache exist, they are commonly underused due to misdiagnosis of the syndrome.[48] Often, it is confused with migraine or other causes of headache.[57]

Treatment for cluster headache is divided into three primary categories: abortive, transitional, and preventative.[49] Some abortive treatments may only decrease the duration or intensity of the headache pain, rather than eliminating it entirely. Transitional treatments are short-term preventative treatments that are intended to relieve the pain whilst seeking a suitable preventative medication. Practitioners will use transitional medication whilst escalating dosages of preventives until these preventive treatments are proven effective, well tolerated, appropriate and become active.[49] Preventive treatment is typically indicated for use in managing chronic cluster headache. Presently, the best hope for the majority of intractable cluster headache sufferers remains specialist physician pain management. [citation needed]

Oxygen

Rapid inhalation of 100% oxygen (oxygen therapy) is used to treat many patients.[48][49][50] Oxygen is typically administered via non-rebreather mask at 7-10 liters per minute for 15–20 minutes.[48][49] Patients who prove unresponsive to 7-10 LPM of Oxygen may have their recommended flow rate increased to 15 LPM.[49]

Refinement of hyperventilation breathing techniques and high-flow O2 demand valve system, has seen promising new results.[58] When oxygen is used at the onset this can abort the attack within a relatively short time. Once an attack has reached its peak, oxygen therapy appears to have less beneficial effect, so many people keep a portable oxygen tank close at hand to use at the very first sign of an attack.[citation needed]

Triptans

First-line cluster headache attack abortive treatment is to initiate subcutaneous,[59] intranasal,[60] or oral[61] administration of sumatriptan.[50] Sumatriptan and zolmitriptan have both been shown to dramatically improve symptoms during an attack or indeed abort an attack completely.[62] Triptans were developed to treat migraines, but have proven over many years to be quite safe and very effective when used as an abortive drug when aborting active cluster headache attack. Because of the vasoconstrictive action of triptans, this drug group may be contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, or circulatory disorders such as Raynaud's disease or syndrome. A high frequency of acute cluster attacks may preclude a maximum dosage of Triptans.

Neurostimulation

Several medical devices are currently in use in preventive treatment of cluster Headache.[63] Neurostimulation devices used in cluster headache treatment typically propose a Neuromodulatory mechanism of action.[64] Both invasive and non-invasive techniques have been used with varying degrees of reported success from patients. Invasive procedures may include surgical implantation of devices for; Occipital Nerve Stimulation (ONS),[65][66] sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) stimulation,[67][68][69] Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS)[70] and hypothalamic Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS).[71] Non-invasive procedures may employ neuromodulatory techniques using non-implantable external devices; Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS).[64] Ongoing research and development of these neuromodulatory techniques is helping to reduce the risks associated with invasive surgical procedures and implantable devices. By making available in some methods, smaller and more portable external stimulation units, neuromodulatory techniques and the medical devices used are gradually becoming less invasive.[72]

Hypothalamus

Among the most widely accepted theories is that cluster headaches are due to a dysfunction of the hypothalamus; Professor Peter Goadsby, an Australian specialist in the disease has developed this theory. This may explain why cluster headaches can frequently strike around the same time each day, and during a particular season. One of the functions the hypothalamus performs is regulation of the biological clock. Metabolic abnormalities have also been reported in patients.

The hypothalamus is responsive to light—daylength and photoperiod; olfactory stimuli, including sex steroids (some researchers have linked low testosterone to cluster headaches)[73][74] and corticosteroids; neurally transmitted information arising in particular from the heart, the stomach, and the reproductive system; autonomic inputs; blood-borne stimuli, including leptin, ghrelin, angiotensin, insulin, pituitary hormones, cytokines, blood plasma concentrations of glucose and osmolarity, etc.; and stress. Vasointestinal polypeptide (VIP), Substance P and Calcitonin gene-related peptide may also play a role.[75][76][77] These particular sensitivities may underlay cluster headache's causes and triggers. Further investigation in these areas may reveal new therapeutic targets, and may help lead researchers into innovative and new novel treatment methods for cluster headache.

|

|

|

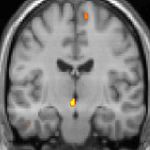

| Positron emission tomography (PET) shows brain areas being activated during pain | ||

|

|

|

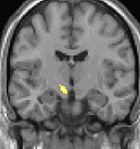

| Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) shows brain area structural differences | ||

The above positron emission tomography (PET) pictures indicate the brain areas which are activated during pain of attack only, compared to pain free periods. These pictures show brain areas which are active during pain in yellow/orange colour (called "pain matrix"). The area in the centre (in all three views) is specifically activated during cluster headache only. The bottom row voxel-based morphometry (VBM) pictures show structural brain differences between cluster headache patients and people without headaches; only a portion of the hypothalamus is different.[78][79]

Genetics

There is speculation of a genetic component to cluster headaches, although no single gene has yet been identified as the cause. One study shows first-degree relatives of sufferers are only slightly more likely to have the condition than the population at large.[80]

Smoking

Tobacco consumption may trigger, or worsen the course of cluster headaches,[81] and the affliction is often found in people with a heavy addiction to cigarette smoking. However it is not clear if there is a causal relationship between smoking and cluster headaches. Some researchers think that people who suffer from cluster headaches may be predisposed to certain traits, including smoking or other lifestyle habits.[82] Some patients report that even exposure to passive smoke can be enough to trigger or worsen attacks.[83]

Opioids

Practitioners will sometimes prescribe opioid narcotic medication in headache conditions, although not indicated for use in the management of cluster headache, opioids will often lead to delayed diagnosis and mismanagement of cluster headache.[84] Neither effective as a preventive, nor an abortive agent in cluster headache, most sufferers will state that opioid medications (Codeine, Morphine) are typically ineffective in managing cluster headache and will most definitely not abort an attack.[84][85] New studies show that opioid medications may present significant risk of actually making the pain of headache syndromes worse.[86][87][88][89][90]

Professor Peter J. Goadsby and Lars Edvinsson demonstrated in a clinical study that both oxygen and sumatriptan effectively abort cluster headache attacks and terminate activity in the trigeminovascular system. Administration of opioids during cluster attack demonstrated no effect on levels of a common therapeutic target; CGRP release (Calcitonin gene-related peptide), where both Sumatriptan and Oxygen therapies were successful in measurably lowering peptide levels (CGRP) and bringing about relief from CH attack.[85] This has raised questions and concern amongst practitioners about whether use of opioid medication in management of chronic cluster headache is at all appropriate, given the lack of efficacy in CH and the known well established long term dependency, addiction and withdrawal syndromes associated with ongoing, long term opioid use.[91][92] Prescription of opioid medication in cluster headache can lead to diagnostic delay, undertreatment, and mismanagement of the condition.[93]

In 2012-2013, in an effort to reduce the amount of imaging, number of consults and number of admissions related to headache whilst maintaining pain relief for patients, pain physicians from the Cleveland clinic are working to refine an algorithm for use in Emergency Department (ED) headache presentations. Details of a report on implementation of the algorithm were presented at the 2013 International Headache Congress and showed an 82% reduction in the use of opioids in Headache presentations in ED. “We were astonished at how much we were able to diminish the use of opiates,” - lead investigator Cynthia Bamford, MD. Further validation of the algorithm will show whether it will hold up in various ED settings.[94][95]

Other

Other therapies that have been trialled include:

- Lithium, melatonin, and anti-convulsant drugs such as valproic acid, topiramate and gabapentin are medications that can be tried as second line treatment options. Various surgical interventions have been tried in treatment-resistant cases but due to the invasiveness, limited evidence of effectiveness and uncertainty regarding adverse effects, in most cases, surgery is not currently a recommended treatment.[96]

- Vasoconstrictors such as ergot compounds are sometimes used immediately at onset of attack. Cafergot, a vasoconstrictor combination of caffeine and ergot, has been demonstrated in some cases to abort cluster headaches within 40 minutes of ingestion. BOL (2-bromo lysergic acid diethylamide), a non-psychedelic form of the ergot-derived psychedelic LSD, has shown promise in the treatment of cluster headaches.[97] Some isolated case reports have also suggested that ingesting LSD, psilocybin or cannabis can reduce cluster headache pain and interrupt cluster headache cycles.[98]

- Treatments such as botox injection have shown mixed levels of success[99]

- Studies performed by dr's R. Andrew Sewell, John H. Halpern and Harrison G. Pope, Jr, have concluded that Psilocybin, LSD and LSA have a significantly higher efficacy rate than any other prescription medicine available. Their study published in Neurology 2006;66, showed that LSD had an 88% and Psilocybin a 52% effectiveness at stopping an active Cluster Headache cycle as opposed to the generally accepted mainstream treatment of Verapamil was only 5% [100]

History

The first complete description of cluster headache was given by the London neurologist Wilfred Harris in 1926. He named the disease Migrainous neuralgia.[101][102][103] Cluster headache symptoms have been described in medical texts as far back as 1745, and probably earlier.[104]

Cluster headaches have been called by several other names in the past including Erythroprosopalgia of Bing, Ciliary neuralgia, Erythromelalgia of the head, Horton's headache (named after Bayard T. Horton, an American neurologist), Histaminic cephalalgia, Petrosal neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, Vidian neuralgia, Sluder's neuralgia, and Hemicrania angioparalyticia.[105]

See also

References

- ^ http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.adelaide.edu.au/painresearch/headache/headache_cluster/[full citation needed]

- ^ a b http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Beck, Ellen; Sieber, William J.; Trejo, Raúl (15 February 2005). "Management of Cluster Headache". American Family Physician. 71 (4): 717–24. PMID 15742909. Cite error: The named reference "pmid15742909" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Cluster Headaches Can Make Life Unbearable". ABC News. 13 June 2001. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ Capobianco, David; Dodick, David (2006). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Cluster Headache". Seminars in Neurology. 26 (2): 242–59. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939925. PMID 16628535.

- ^ Marmura, M. J.; Pello, S. J.; Young, W. B. (2010). "Interictal pain in cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 30 (12): 1531–4. doi:10.1177/0333102410372423. PMID 20974600.

- ^ Meyer, Eva Laudon; Laurell, Katarina; Artto, Ville; Bendtsen, Lars; Linde, Mattias; Kallela, Mikko; Tronvik, Erling; Zwart, John-Anker; Jensen, Rikke M.; Hagen, Knut (2009). "Lateralization in cluster headache: A Nordic multicenter study". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 10 (4): 259–63. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0129-z. PMC 3451747. PMID 19495933.

- ^ Matharu, Manjit; Goadsby, Peter (2001). "Cluster Headache". Practical Neurology. 1: 42. doi:10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00505.x.

- ^ Presenter: Natasha Mitchell. Producer: Brigitte Seega (9 August 1999). "Cluster Headaches". Health Report. Radio National.

- ^ http://www.nbcnews.com/health/brain-freeze-agony-ecstasy-ice-cream-1C6437739[full citation needed]

- ^ Horton BT, MacLean AR, Craig W.: A New Syndrome of Vascular Headache: Results of Treatment with Histamine. Proc Staff Meet, Mayo Clinic (1939) 14:257

- ^ "IHS/ICHD-II 3.1 Cluster headache". Ihs-classification.org. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ Robbins, Matthew S. (2013). "The Psychiatric Comorbidities of Cluster Headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 17 (2). doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0313-8.

- ^ Liang, J.-F.; Chen, Y.-T.; Fuh, J.-L.; Li, S.-Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Chen, T.-J.; Tang, C.-H.; Wang, S.-J. (2012). "Cluster headache is associated with an increased risk of depression: A nationwide population-based cohort study". Cephalalgia. 33 (3): 182–9. doi:10.1177/0333102412469738. PMID 23212294.

- ^ Jensen, RM; Lyngberg, A; Jensen, RH (2007). "Burden of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 27 (6): 535–41. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01330.x. PMID 17459083.

- ^ Pringsheim, T (2002). "Cluster headache: Evidence for a disorder of circadian rhythm and hypothalamic function". The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 29 (1): 33–40. PMID 11858532.

- ^ Dodick, David W.; Eross, Eric J.; Parish, James M.; Silber, M (2003). "Clinical, Anatomical, and Physiologic Relationship Between Sleep and Headache". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 43 (3): 282–92. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03055.x. PMID 12603650.

- ^ "IHS Classification ICHD-II 3.1.2 Chronic cluster headache". Ihs-classification.org. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ Torelli, P; Manzoni, GC (2002). "What predicts evolution from episodic to chronic cluster headache?". Current pain and headache reports. 6 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1007/s11916-002-0026-5. PMID 11749880.

- ^ "Diamond Headache Clinc". Diamondheadache.com. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Torelli P, Castellini P, Cucurachi L, Devetak M, Lambru G, Manzoni G (2006). "Cluster headache prevalence: methodological considerations. A review of the literature". Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 77 (1): 4–9. PMID 16856701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/05/16/researcher-unlocking-mysteries-migraines/2165363/[full citation needed]

- ^ Goadsby, P. J. (2008). "The vascular theory of migraine--a great story wrecked by the facts". Brain. 132 (1): 6–7. doi:10.1093/brain/awn321. PMID 19098031.

- ^ Leone, Massimo; Orsucci, Alberto Proietti; Ienco, Vincenzo; Pini, Marcella; Choub, Paola; Siciliano, Gennaro (2013). "Cluster headache: What has changed since 1999?". Neurological Sciences. 34 (1): 71–4. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1365-1. PMID 22193419.

- ^ "Vast Majority of Cluster Headache Patients Are Initially Misdiagnosed, Dutch Researchers Report". World Headache Alliance. 21 August 2003. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ http://www.springerplus.com/content/2/1/4

- ^ http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.00.00_cluster.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/160003/NPS_Headache_Diary_0612.pdf[full citation needed]

- ^ Jensen, Rigmor; Tfelt-Hansen, Peer (2013). "Det vigtigste spørgsmål ved svær hovedpine er varigheden af hovedpineanfaldet". Ugeskrift for Læger (in Danish). 175 (6): 361–2. PMID 23402243.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman, Benjamin Wolkin; Grosberg, Brian Mitchell (2009). "Diagnosis and Management of the Primary Headache Disorders in the Emergency Department Setting". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 27 (1): 71–87, viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2008.09.005. PMC 2676687. PMID 19218020.

- ^ Bahra, A.; Goadsby, P. J. (2004). "Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 109 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00237.x. PMID 14763953.

- ^ Van Vliet, J A; Eekers, PJ; Haan, J; Ferrari, MD; Dutch Russh Study, Group (2003). "Features involved in the diagnostic delay of cluster headache". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 74 (8): 1123–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1123. PMC 1738593. PMID 12876249.

- ^ Van Alboom, E; Louis, P; Van Zandijcke, M; Crevits, L; Vakaet, A; Paemeleire, K (2009). "Diagnostic and therapeutic trajectory of cluster headache patients in Flanders". Acta neurologica Belgica. 109 (1): 10–7. PMID 19402567.

- ^ Klapper, Jack A.; Klapper, Amy; Voss, Tracy (2000). "The Misdiagnosis of Cluster Headache: A Nonclinic, Population-Based, Internet Survey". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 40 (9): 730–5. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00127.x. PMID 11091291.

- ^ Geweke, Lynne O. (2002). "Misdiagnosis of cluster headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 6 (1): 76–82. doi:10.1007/s11916-002-0028-3. PMID 11749882.

- ^ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000786.htm[full citation needed]

- ^ Clarke, C E; Edwards, J; Nicholl, DJ; Sivaguru, A; Davies, P; Wiskin, C (2005). "Ability of a nurse specialist to diagnose simple headache disorders compared with consultant neurologists". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 76 (8): 1170–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.057968. PMC 1739753. PMID 16024902.

- ^ Ahmed, F. (2012). "Headache disorders: Differentiating and managing the common subtypes". British Journal of Pain. 6 (3): 124–32. doi:10.1177/2049463712459691.

- ^ http://www.touchneurology.com/articles/cluster-headache-diagnosis-and-treatment[full citation needed]

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11091291, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11091291instead. - ^ http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.02.00_cluster.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.03.00_cluster.html

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16517438, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16517438instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/head.12007, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/head.12007instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19402567, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19402567instead. - ^ http://bjp.sagepub.com/content/6/3/106

- ^ a b c d e f g h ELLEN BECK, M.D., WILLIAM J. SIEBER, PH.D., and RAÚL TREJO, M.D. (15 February 2005). "Management of Cluster Headache". American Family Physician. 71 (4): 717–724. PMID 15742909. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Michigan Headache & Neurological Institute. "Cluster Headache Update". Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d May A, Leone M, Afra J, Linde M, Sándor P, Evers S, Goadsby P (2006). "EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias". Eur J Neurol. 13 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x. PMID 16987158.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free Full Text (PDF) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17698788, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17698788instead. - ^ Mauskop A, Altura BT, Cracco RQ, Altura BM (1995). "Intravenous magnesium sulfate relieves cluster headaches in patients with low serum ionized magnesium levels". Headache. 35 (10): 597–600. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3510597.x. PMID 8550360.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ashina, M. (2000). "Nitric oxide-induced headache in patients with chronic tension-type headache". Brain. 123 (9): 1830. doi:10.1093/brain/123.9.1830.

- ^ Dahl, A; Russell, D; Nyberg-Hansen, R; Rootwelt, K (1990). "Cluster headache: Transcranial Doppler ultrasound and rCBF studies". Cephalalgia. 10 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1990.1002087.x. PMID 2113834.

- ^ Daugaard, Dorthe; Tfelt-Hansen, Peer; Thomsen, Lars Lykke; Iversen, Helle Klingenberg; Olesen, Jes (2010). "No effect of pure oxygen inhalation on headache induced by glyceryl trinitrate". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 11 (2): 93–5. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0190-7. PMC 3452287. PMID 20143247.

- ^ http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/drugs-inc/videos/magic-mushroom-medicine/

- ^ "Vast Majority of Cluster Headache Patients Are Initially Misdiagnosed, Dutch Researchers Report". World Headache Alliance. 21 August 2003. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23369112, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23369112instead. - ^ Ekbom, K; Krabbe, A; Micieli, G; Prusinski, A; Cole, JA; Pilgrim, AJ; Noronha, D; Micelli G [corrected to Micieli G] (1995). "Cluster headache attacks treated for up three months with subcutaneous sumatriptan (6 mg)". Cephalalgia. 15 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.015003230.x. PMID 7553814.

- ^ Rapoport, A. M.; Mathew, N. T.; Silberstein, S. D.; Dodick, D.; Tepper, S. J.; Sheftell, F. D.; Bigal, M. E. (2007). "Zolmitriptan nasal spray in the acute treatment of cluster headache: A double-blind study". Neurology. 69 (9): 821–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000267886.85210.37. PMID 17724283.

- ^ Bahra, A.; Gawel, M. J.; Hardebo, J.-E.; Millson, D.; Breen, S. A.; Goadsby, P. J. (2000). "Oral zolmitriptan is effective in the acute treatment of cluster headache". Neurology. 54 (9): 1832–9. doi:10.1212/WNL.54.9.1832. PMID 10802793.

- ^ Law, Simon; Derry, Sheena; Moore, R Andrew (2010). Law, Simon (ed.). "Triptans for acute cluster headache". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD008042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008042.pub2. PMID 20393964.

- ^ Bartsch, Thorsten; Paemeleire, Koen; Goadsby, Peter J (2009). "Neurostimulation approaches to primary headache disorders". Current Opinion in Neurology. 22 (3): 262–8. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832ae61e. PMID 19434793.

- ^ a b http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Fact_Sheets4&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=14465

- ^ Burns, Brian; Watkins, Laurence; Goadsby, Peter J (2007). "Treatment of medically intractable cluster headache by occipital nerve stimulation: Long-term follow-up of eight patients". The Lancet. 369 (9567): 1099–106. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60328-6. PMID 17398309.

- ^ Magis, Delphine; Allena, Marta; Bolla, Monica; De Pasqua, Victor; Remacle, Jean-Michel; Schoenen, Jean (2007). "Occipital nerve stimulation for drug-resistant chronic cluster headache: A prospective pilot study". The Lancet Neurology. 6 (4): 314–21. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70058-3. PMID 17362835.

- ^ Schoenen, J.; Jensen, R. H.; Lantéri-Minet, M.; Láinez, M. J.; Gaul, C.; Goodman, A. M.; Caparso, A.; May, A. (2013). "Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: A randomized, sham-controlled study". Cephalalgia. 33 (10): 816–30. doi:10.1177/0333102412473667. PMC 3724276. PMID 23314784.

- ^ Goadsby, P. J. (2013). "Sphenopalatine (pterygopalatine) ganglion stimulation and cluster headache: New hope for ye who enter here". Cephalalgia. 33 (10): 813–5. doi:10.1177/0333102413482195. PMC 3724280. PMID 23575817.

- ^ Ansarinia, Mehdi; Rezai, Ali; Tepper, Stewart J.; Steiner, Charles P.; Stump, Jenna; Stanton-Hicks, Michael; Machado, Andre; Narouze, Samer (2010). "Electrical Stimulation of Sphenopalatine Ganglion for Acute Treatment of Cluster Headaches". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 50 (7): 1164–74. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01661.x. PMID 20438584.

- ^ Mauskop, A (2005). "Vagus nerve stimulation relieves chronic refractory migraine and cluster headaches". Cephalalgia. 25 (2): 82–6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00611.x. PMID 15658944.

- ^ Leone, M; Proietti Cecchini, A; Franzini, A; Broggi, G; Cortelli, P; Montagna, P; May, A; Juergens, T; Cordella, R; Carella, F; Bussone, G (2008). "Lessons from 8 years' experience of hypothalamic stimulation in cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 28 (7): 787–97, discussion 798. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01627.x. PMID 18547215.

- ^ http://www.migrainetrust.org/research-article-neurostimulation-devices-in-headache-treatment-2013-17097[full citation needed]

- ^ Stillman, Mark J. (2006). "Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Treatment Refractory Cluster Headache". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 46 (6): 925–33. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00436.x. PMID 16732838.

- ^ Ceccarelli, I.; De Padova, A.M.; Fiorenzani, P.; Massafra, C.; Aloisi, A.M. (2006). "Single opioid administration modifies gonadal steroids in both the CNS and plasma of male rats". Neuroscience. 140 (3): 929–37. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.044. PMID 16580783.

- ^ Nicolodi, M; Del Bianco, E (1990). "Sensory neuropeptides (substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in human saliva: Their pattern in migraine and cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 10 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1990.1001039.x. PMID 1690601.

- ^ Goadsby, PJ; Edvinsson, L (1994). "Human in vivo evidence for trigeminovascular activation in cluster headache. Neuropeptide changes and effects of acute attacks therapies". Brain. 117 (3): 427–34. doi:10.1093/brain/117.3.427. PMID 7518321.

- ^ Vincent, MB (1992). "Lithium inhibits substance P and vasoactive intestinal peptide-induced relaxations on isolated porcine ophthalmic artery". Headache. 32 (7): 335–9. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1992.hed3207335.x. PMID 1382046.

- ^ May, A.; Bahra, A.; Büchel, C.; Frackowiak, R. S. J.; Goadsby, P. J. (2000). "PET and MRA findings in cluster headache and MRA in experimental pain". Neurology. 55 (9): 1328–35. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.9.1328. PMID 11087776.

- ^ Dasilva, Alexandre F. M.; Goadsby, Peter J.; Borsook, David (2007). "Cluster headache: A review of neuroimaging findings". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 11 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-007-0010-1. PMID 17367592.

- ^ Pinessi, L.; Rainero, I.; Rivoiro, C.; Rubino, E.; Gallone, S. (2005). "Genetics of cluster headache: An update". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 6 (4): 234–6. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0194-x. PMC 3452030. PMID 16362673.

- ^ Tiraferri, I; Righi, F; Zappaterra, M; Ciccarese, M; Pini, LA; Ferrari, A; Cainazzo, MM (2013). "Can cigarette smoking worsen the clinical course of cluster headache?". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 1 (Suppl 1): P54. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-1-S1-P54.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Schürks, Markus; Diener, Hans-Christoph (2008). "Cluster headache and lifestyle habits". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 12 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0022-5. PMID 18474191.

- ^ Rozen, Todd D. (2010). "Cluster Headache As the Result of Secondhand Cigarette Smoke Exposure During Childhood". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 50: 130. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01542.x.

- ^ a b http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1872057/

- ^ a b Goadsby, Peter J.; Edvinsson, Lars (1994). "Human in vivo evidence for trigeminovascular activation in cluster headache Neuropeptide changes and effects of acute attacks therapies". Brain. 117 (3): 427–34. doi:10.1093/brain/117.3.427. PMID 7518321.

- ^ http://www.neurologyreviews.com/the-publication/issue-single-view/codeine-and-morphine-may-increase-pain-sensitivity-equally/382d2c385b5e3154bbed15156f33e46c.html

- ^ Siegel, Shepard (1975). "Evidence from rats that morphine tolerance is a learned response". Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 89 (5): 498–506. doi:10.1037/h0077058. PMID 425.

- ^ http://www.adelaide.edu.au/news/news64625.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Johnson, J. L.; Hutchinson, M. R.; Williams, D. B.; Rolan, P. (2012). "Medication-overuse headache and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: A review of mechanisms, a neuroimmune hypothesis and a novel approach to treatment". Cephalalgia. 33 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1177/0333102412467512. PMID 23144180.

- ^ Watkins, Linda R.; Hutchinson, Mark R.; Rice, Kenner C.; Maier, Steven F. (2009). "The "Toll" of Opioid-Induced Glial Activation: Improving the Clinical Efficacy of Opioids by Targeting Glia". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 30 (11): 581–91. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.002. PMC 2783351. PMID 19762094.

- ^ Paemeleire, K.; Bahra, A.; Evers, S.; Matharu, M. S.; Goadsby, P. J. (2006). "Medication-overuse headache in patients with cluster headache". Neurology. 67 (1): 109–13. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000223332.35936.6e. PMID 16832088.

- ^ Saper, Joel R.; Da Silva, Arnaldo Neves (2013). "Medication Overuse Headache: History, Features, Prevention and Management Strategies". CNS Drugs. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0081-y.

- ^ Paemeleire, K; Evers, S; Goadsby, PJ (2008). "Medication-overuse headache in patients with cluster headache". Current pain and headache reports. 12 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0023-4. PMID 18474192.

- ^ http://www.anesthesiologynews.com/ViewArticle.aspx?d=Pain%2BMedicine&d_id=2&i=October+2013&i_id=1002&a_id=24199

- ^ https://www.icsi.org/_asset/qwrznq/Headache.pdf

- ^ Chen PK, Chen HM, Chen WH; et al. (2011). "[Treatment guidelines for acute and preventive treatment of cluster headache]" (PDF). Acta Neurol Taiwan (in Chinese). 20 (3): 213–27. PMID 22009127.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Treatment of Cluster Headaches Using 2-Bromo-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. The Beckley Foundation

- ^ Sun-Edelstein, Christina; Mauskop, Alexander (2011). "Alternative Headache Treatments: Nutraceuticals, Behavioral and Physical Treatments". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 51 (3): 469–83. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x. PMID 21352222.

- ^ Sostak P, Krause P, Förderreuther S, Reinisch V, Straube A (2007). "Botulinum toxin type-A therapy in cluster headache: an open study". J Headache Pain. 8 (4): 236–41. doi:10.1007/s10194-007-0400-0. PMID 17901920.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sewell, Andrew; Halpern, John; Pope, Harrison (2006). "Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD". Neurology. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219761.05466.43.

- ^ Harris W.: Neuritis and Neuralgia. Oxford: Oxford Univ.Press; 1926[page needed]

- ^ Bickerstaff, Edwinr. (1959). "The Periodic Migrainous Neuralgia of Wilfred Harris". The Lancet. 273 (7082): 1069. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90651-8.

- ^ Boes, CJ; Capobianco, DJ; Matharu, MS; Goadsby, PJ (2002). "Wilfred Harris' early description of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 22 (4): 320–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00360.x. PMID 12100097.

- ^ Pearce, JMS. "Gerardi van Swieten: descriptions of episodic cluster headache" http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2117620/

- ^ Stephen D. Silberstein, Richard B. Lipton. Peter J. Goadsgy. "Headache in Clinical Practice." Second edition. Taylor & Francis. 2002.[page needed]