Bronchitis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

[[Acute bronchitis]] is a self-limited [[lower respiratory tract infection|infection of the lower respiratory tract]] causing inflammation of the [[bronchi]]. Acute bronchitis is an acute illness lasting less than three weeks with [[cough]]ing as the main symptom, and at least one other lower respiratory tract symptom such as [[wheezing]], [[sputum]] production, or chest pain.<ref name="Family"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/135/basics.html |title=Definition |author=BMJ Evidence Centre |year=2012 |work=Acute bronchitis Basics |publisher=BMJ Publishing Group |accessdate=6 January 2013}}</ref> |

[[Acute bronchitis]] is a self-limited [[lower respiratory tract infection|infection of the lower respiratory tract]] causing inflammation of the [[bronchi]]. Acute bronchitis is an acute illness lasting less than three weeks with [[cough]]ing as the main symptom, and at least one other lower respiratory tract symptom such as [[wheezing]], [[sputum]] production, or chest pain.<ref name="Family"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/135/basics.html |title=Definition |author=BMJ Evidence Centre |year=2012 |work=Acute bronchitis Basics |publisher=BMJ Publishing Group |accessdate=6 January 2013}}</ref> |

||

The coughing, |

The coughing, which is a common symptom of the acute bronchitis,<ref name="Acute"/> develops in an attempt to expel the excess mucus from the lungs.<ref name="treatment">{{cite web|url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/bronchitis/DS00031/DSECTION=treatments%2Dand%2Ddrugs|title=Bronchitis: Treatment and drugs |author=Mayo Clinic Staff |year=2011 |work= |publisher=Mayo Clinic Staff |accessdate=27 December 2012}}</ref> Other common symptoms of acute bronchitis include: [[sore throat]], [[dyspnea|shortness of breath]], [[Fatigue (medical)|fatigue]], [[Rhinorrhea|runny nose]], [[nasal congestion]] ([[coryza]]), low-grade [[fever]], [[pleurisy]], [[malaise]], and the production of sputum.<ref name="ID"/><ref name="Acute"/><ref name="Mayo2">{{cite web|url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/bronchitis/DS00031/DSECTION=symptoms|title=Bronchitis: Symptoms |author=Mayo Clinic Staff |year=2011 |work= |publisher=Mayo Clinic |accessdate=27 December 2012}}</ref> |

||

Acute bronchitis is most often caused by [[virus]]es that infect the [[epithelium]] of the bronchi, resulting in inflammation and increased secretion of [[mucus]].<ref name="Acute">{{cite web|url=http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001087.htm|title=Bronchitis-acute |author=U.S. National Library of Medicine |year=2012 |work= |publisher=National Institutes of Health |accessdate=27 December 2012}}</ref> Acute bronchitis often develops during an [[upper respiratory infection]] (URI) such as the [[common cold]] or [[influenza]].<ref name="Mayo"/><ref name="ID"/><ref name="Acute"/> About 90% of cases of acute bronchitis are caused by viruses, including [[rhinovirus]]es, [[coronavirus]]es, [[adenovirus]]es, [[metapneumovirus]], [[parainfluenza virus]], [[respiratory syncytial virus]], and [[influenza]].<ref name="Family"/> Certain viruses such as rhinoviruses and coronaviruses are also known to cause acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.<ref name="Harrisons">{{cite book|author=Fauci, Anthony S.|coauthors=Daniel L. Kasper, Dan L. Longo, Eugene Braunwald, Stephen L. Hauser, J. Larry Jameson|title=''Chapter 179. Common Viral Respiratory Infections and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)'' Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine|year=2008|publisher=McGraw-Hill|location=New York|isbn=978-0-07-147691-1|edition=17th ed.}}</ref> About 10% of cases are caused by [[bacteria]],<ref name="ID"/> including ''[[Mycoplasma pneumoniae]]'',<ref name="Family"/> ''[[Chlamydophila pneumoniae]]'',<ref name="Family"/>'' [[Bordetella pertussis]]'',<ref name="Family"/> ''[[Streptococcus pneumoniae]]'', and ''[[Haemophilus influenzae]]''. |

Acute bronchitis is most often caused by [[virus]]es that infect the [[epithelium]] of the bronchi, resulting in inflammation and increased secretion of [[mucus]].<ref name="Acute">{{cite web|url=http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001087.htm|title=Bronchitis-acute |author=U.S. National Library of Medicine |year=2012 |work= |publisher=National Institutes of Health |accessdate=27 December 2012}}</ref> Acute bronchitis often develops during an [[upper respiratory infection]] (URI) such as the [[common cold]] or [[influenza]].<ref name="Mayo"/><ref name="ID"/><ref name="Acute"/> About 90% of cases of acute bronchitis are caused by viruses, including [[rhinovirus]]es, [[coronavirus]]es, [[adenovirus]]es, [[metapneumovirus]], [[parainfluenza virus]], [[respiratory syncytial virus]], and [[influenza]].<ref name="Family"/> Certain viruses such as rhinoviruses and coronaviruses are also known to cause acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.<ref name="Harrisons">{{cite book|author=Fauci, Anthony S.|coauthors=Daniel L. Kasper, Dan L. Longo, Eugene Braunwald, Stephen L. Hauser, J. Larry Jameson|title=''Chapter 179. Common Viral Respiratory Infections and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)'' Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine|year=2008|publisher=McGraw-Hill|location=New York|isbn=978-0-07-147691-1|edition=17th ed.}}</ref> About 10% of cases are caused by [[bacteria]],<ref name="ID"/> including ''[[Mycoplasma pneumoniae]]'',<ref name="Family"/> ''[[Chlamydophila pneumoniae]]'',<ref name="Family"/>'' [[Bordetella pertussis]]'',<ref name="Family"/> ''[[Streptococcus pneumoniae]]'', and ''[[Haemophilus influenzae]]''. |

||

Revision as of 12:28, 18 February 2014

| Bronchitis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

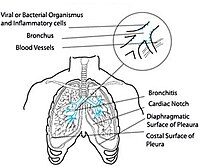

Bronchitis is an inflammation of the mucous membranes of the bronchi (the larger and medium-sized airways that carry airflow from the trachea into the more distal parts of the lung parenchyma).[1][2][3] Bronchitis can be divided into two categories: acute and chronic.[1][2][3][4]

Acute bronchitis is characterized by the development of a cough or small sensation in the back of the throat, with or without the production of sputum (mucus that is expectorated, or "coughed up", from the respiratory tract). Acute bronchitis often occurs during the course of an acute viral illness such as the common cold or influenza. Viruses cause about 90% of acute bronchitis cases, whereas bacteria account for about 10%.[5][6]

Chronic bronchitis, a type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is characterized by the presence of a productive cough that lasts for three months or more per year for at least two years. Chronic bronchitis usually develops due to recurrent injury to the airways caused by inhaled irritants. Cigarette smoking is the most common cause, followed by exposure to air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide or nitrogen dioxide,[7] and occupational exposure to respiratory irritants.[6][8] Individuals exposed to cigarette smoke, chemical lung irritants, or who are immunocompromised have an increased risk of developing bronchitis.[9]

Acute bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is a self-limited infection of the lower respiratory tract causing inflammation of the bronchi. Acute bronchitis is an acute illness lasting less than three weeks with coughing as the main symptom, and at least one other lower respiratory tract symptom such as wheezing, sputum production, or chest pain.[5][10]

The coughing, which is a common symptom of the acute bronchitis,[11] develops in an attempt to expel the excess mucus from the lungs.[12] Other common symptoms of acute bronchitis include: sore throat, shortness of breath, fatigue, runny nose, nasal congestion (coryza), low-grade fever, pleurisy, malaise, and the production of sputum.[6][11][13]

Acute bronchitis is most often caused by viruses that infect the epithelium of the bronchi, resulting in inflammation and increased secretion of mucus.[11] Acute bronchitis often develops during an upper respiratory infection (URI) such as the common cold or influenza.[2][6][11] About 90% of cases of acute bronchitis are caused by viruses, including rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza.[5] Certain viruses such as rhinoviruses and coronaviruses are also known to cause acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.[14] About 10% of cases are caused by bacteria,[6] including Mycoplasma pneumoniae,[5] Chlamydophila pneumoniae,[5] Bordetella pertussis,[5] Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae.

Bronchitis may be diagnosed by a health care provider during a thorough physical examination. Due to the nonspecific signs and symptoms exhibited by individuals with bronchitis, diagnostic tests such as a chest x-ray to rule out pneumonia, a sputum culture to rule out whooping cough or other bacterial respiratory infections, or a pulmonary function test to rule out asthma or emphysema may be used.[15]

Treatment for acute bronchitis is primarily symptomatic. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to treat fever and sore throat. Even with no treatment, most cases of acute bronchitis resolve quickly.[6]

As most cases of acute bronchitis are caused by viruses, antibiotics are not generally recommended as they are only effective against bacteria.[8][12] Using antibiotics in cases of viral bronchitis promotes the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which may lead to greater morbidity and mortality.[5] However, even in cases of viral bronchitis, antibiotics may be indicated in certain cases in order to prevent the occurrence of secondary bacterial infections.[12]

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis, a type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, defined by a productive cough that lasts greater than three months each year for at least two years in the absence of other underlying disease.[3] Protracted bacterial bronchitis is defined as a chronic productive cough with a positive bronchoalveolar lavage that resolves with antibiotics.[16][17]

Symptoms of chronic bronchitis may include wheezing and shortness of breath, especially upon exertion and low oxygen saturations.[18] The cough is often worse soon after awakening and the sputum produced may have a yellow or green color and may be streaked with specks of blood.[6]

Most cases of chronic bronchitis are caused by smoking cigarettes or other forms of tobacco.[3][18][19] Additionally, chronic inhalation of air pollution or irritating fumes or dust from hazardous exposures in occupations such as coal mining, grain handling, textile manufacturing, livestock farming,[20] and metal moulding may also be a risk factor for the development of chronic bronchitis.[21][22][23]

Protracted bacterial bronchitis is usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Non-typable Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.[16][17]

Individuals with an obstructive pulmonary disorder such as bronchitis may present with a decreased FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio on pulmonary function tests.[24][25][26] Unlike other common obstructive disorders such as asthma or emphysema, bronchitis rarely causes a high residual volume (the volume of air remaining in the lungs after a maximal exhalation effort).[27]

Evidence suggests that the decline in lung function observed in chronic bronchitis may be slowed with smoking cessation.[28] Chronic bronchitis is treated symptomatically and may be treated in a nonpharmacologic manner or with pharmacologic therapeutic agents. Typical nonpharmacologic approaches to the management of COPD including bronchitis may include: pulmonary rehabilitation, lung volume reduction surgery, and lung transplantation.[28] Inflammation and edema of the respiratory epithelium may be reduced with inhaled corticosteroids.[29] Wheezing and shortness of breath can be treated by reducing bronchospasm (reversible narrowing of smaller bronchi due to constriction of the smooth muscle) with bronchodilators such as inhaled long acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonists (e.g., salmeterol) and inhaled anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide or tiotropium bromide.[30] Mucolytics may have a small therapeutic effect on acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.[31] Supplemental oxygen is used to treat hypoxemia (too little oxygen in the blood) and has been shown to reduce mortality in chronic bronchitis patients.[6][28] Oxygen supplementation can result in decreased respiratory drive, leading to increased blood levels of carbon dioxide (hypercapnea) and subsequent respiratory acidosis.[32]

References

- ^ a b National Lung, Heart, and Blood Institute (2012). "Chronic Bronchitis". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis Definition". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Understanding Chronic Bronchitis". American Lung Association. 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Lee Goldman, Dennis Ausiello (2004). Cecil textbook of medicine (22nd ed. ed.). Philadelphia, Penns.: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-9652-2.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Albert, RH (December 2010). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis". American Family Physician. 82 (11): 1345–1350. PMID 21121518.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cohen, Jonathan; Powderly, William (2004). Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed. Mosby (Elsevier). Chapter 33: Bronchitis, Bronchiectasis, and Cystic Fibrosis. ISBN 0323025730.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay (2007). Chapter 13. The Lung Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis: Causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis: Risk factors". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ BMJ Evidence Centre (2012). "Definition". Acute bronchitis Basics. BMJ Publishing Group. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d U.S. National Library of Medicine (2012). "Bronchitis-acute". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis: Treatment and drugs". Mayo Clinic Staff. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis: Symptoms". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S. (2008). Chapter 179. Common Viral Respiratory Infections and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17th ed. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147691-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (2011). "Bronchitis: Tests and diagnosis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b Goldsobel, AB; Chipps, BE (March 2010). "Cough in the pediatric population". The Journal of Pediatrics. 156 (3): 352–358.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.004. PMID 20176183.

- ^ a b Craven, V; Everard, ML (January 2013). "Protracted bacterial bronchitis: reinventing an old disease". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 98 (1): 72–76. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-302760. PMID 23175647.

- ^ a b U.S. National Library of Medicine (2011). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Forey, BA; Thornton, AJ; Lee, PN (June 2011). "Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to COPD, chronic bronchitis and emphysema". BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 11 (36). doi:10.1186/1471-2466-11-36. PMID 21672193.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Szczyrek, M; Krawczyk, P; Milanowski, J; Jastrzebska, I; Zwolak, A; Daniluk, J (2011). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in farmers and agricultural workers-an overview". Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 18 (2): 310–313. PMID 22216804.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Fischer, BM; Pavlisko, E; Voynow, JA (2011). "Pathogenic triad in COPD: oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and inflammation". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 6: 413–421. doi:10.2147/COPD.S10770. PMID 21857781.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (2009). "Who Is at Risk for Bronchitis?". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (2012). "Respiratory Diseases Input: Occupational Risks". NIOSH Program Portfolio. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Respiratory Health Spirometry Procedures Manual" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Willemse, BW; Postma, DS; Timens, W; ten Hacken, NH (March 2004). "The impact of smoking cessation on respiratory symptoms, lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation". The European respiratory journal: official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 23 (3): 464–476. PMID 15065840.

- ^ Mohamed Hoesein, FA; Zanen, P; Lammers, JW (June 2011). "Lower limit of normal or FEV1/FVC<0.70 in diagnosing COPD: an evidence-based review". Respiratory medicine. 105 (6): 907–915. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.008. PMID 21295958.

- ^ Wanger, J; Clausen, JL; Coates, A; Pedersen, OF; Brusasco, V; Burgos, F; Casaburi, R; Crapo, R; Enright, P (September 2005). "Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes". The European respiratory journal: official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 26 (3): 511–522. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. PMID 16135736.

- ^ a b c Fauci, Anthony S. (2008). Chapter 254. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147691-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Spencer, S; Karner, C; Cates, CJ; Evans, DJ (2011). "Inhaled corticosteroids versus long acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (CD007033). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007033.pub3. PMID 22161409.

- ^ Karner, C; Chong, J; Poole, P (2012). "Tiotropium versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (CD009285). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009285.pub2. PMID 22786525.

- ^ Poole, P; Black, PN; Cates, CJ (2012). "Mucolytic agents for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (CD001287). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001287.pub4. PMID 22895919.

- ^ Iscoe, S; Beasley, R; Fisher, JA (2011). "Supplementary oxygen for nonhypoxemic patients:O2 much of a good thing?". Critical Care. 15 (3): 305. doi:10.1186/cc10229. PMC 3218982. PMID 21722334.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

- NIH entry on Bronchitis

- MedlinePlus entries on Acute bronchitis and Chronic bronchitis

- Mayo Clinic factsheet on bronchitis