Salmon P. Chase: Difference between revisions

→Chief Justice of the United States: removed unsourced info, not relevant to tenure as CJOTUS |

|||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

As Chief Justice, Chase also presided at the [[Impeachment of Andrew Johnson|impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson]] in 1868. |

As Chief Justice, Chase also presided at the [[Impeachment of Andrew Johnson|impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson]] in 1868. |

||

He gradually drifted back toward his old Democratic allegiance, and made an unsuccessful effort to secure the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1868. He "was passed over because of his stance in favor of voting rights for black men".<ref name=HarpWeek/> In 1871, The New Departure policy of Ohio Democrat [[Clement Vallandigham]] was endorsed by Chase.<ref>p. 446, Vallandigham, James L. A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham. Baltimore, MD: Turnbull Brothers, 1872.</ref> He helped found the [[Liberal Republican Party (United States)|Liberal Republican Party]] in 1872, unsuccessfully seeking its presidential nomination. |

He gradually drifted back toward his old Democratic allegiance, and made an unsuccessful effort to secure the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1868. He "was passed over because of his stance in favor of voting rights for black men".<ref name=HarpWeek/> In 1871, The New Departure policy of Ohio Democrat [[Clement Vallandigham]] was endorsed by Chase.<ref>p. 446, Vallandigham, James L. A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham. Baltimore, MD: Turnbull Brothers, 1872.</ref> He helped found the [[Liberal Republican Party (United States)|Liberal Republican Party]] in 1872, unsuccessfully seeking its presidential nomination. |

||

As early as 1868 Chase concluded that: |

As early as 1868 Chase concluded that: |

||

Revision as of 16:50, 16 February 2015

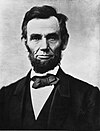

Salmon P. Chase | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office December 15, 1864[1] – May 7, 1873 | |

| Nominated by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Roger B. Taney |

| Succeeded by | Morrison R. Waite |

| 25th United States Secretary of the Treasury | |

| In office March 7, 1861 – June 30, 1864 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | John A. Dix |

| Succeeded by | William P. Fessenden |

| 23rd Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 14, 1856 – January 9, 1860 | |

| Lieutenant | Thomas H. Ford Martin Welker |

| Preceded by | William Medill |

| Succeeded by | William Dennison |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office March 4, 1849 – March 3, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | William Allen |

| Succeeded by | George E. Pugh |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 7, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | George E. Pugh |

| Succeeded by | John Sherman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Salmon Portland Chase January 13, 1808 Cornish, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | May 7, 1873 (aged 65) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Free Soil, Liberty, Republican, Democrat |

| Spouse(s) | Katherine Garmiss Chase Eliza Ann Smith Chase Sarah Dunlop Ludlow Chase[2] |

| Children | 2 (Kate Chase, b. 1840) |

| Alma mater | Cincinnati College Dartmouth College |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer, Judge |

| Signature | |

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808 – May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as U.S. Senator from Ohio and the 23rd Governor of Ohio[citation needed]; as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Abraham Lincoln; and as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States.[3]

Chase articulated the "slave power conspiracy" thesis, devoting his energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power[citation needed]—the conspiracy of Southern slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. He coined the slogan of the Free Soil Party, "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men". Chief Justice Chase presided over the Senate trial of Andrew Johnson during the President's impeachment proceedings in 1868.

Early life and education

Chase was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, to Janet Ralston and Ithamar Chase, who died in 1817 when Salmon was nine years old[citation needed]. His mother was left with ten children and few resources, and so Salmon lived from 1820 to 1824 in Ohio with his uncle Bishop Philander Chase, a leading figure in the Protestant Episcopal Church in the West. U.S. Senator Dudley Chase of Vermont was another uncle.[4]

He studied in the common schools of Windsor, Vermont, and Worthington, Ohio, and at Cincinnati College before entering the junior class at Dartmouth College.[3] He was a member of the Alpha Delta Phi Fraternity and Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated from Dartmouth in 1826. While at Dartmouth, he taught at the Royalton Academy in Royalton, Vermont. Chase then moved to the District of Columbia, where he studied law under U.S. Attorney General William Wirt and continued to teach. He was admitted to the bar in 1829.[3]

Entrance into politics

In 1830[citation needed] Chase moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he quickly gained a position of prominence at the bar as an abolitionist lawyer.[5] He maintained a country home near Loveland.[6] He published an annotated edition of the laws of Ohio which was long considered a standard. The death of his first wife, Katherine Jane Garmiss, in 1835, shortly after their wedding in March 1834, triggered Chase's spiritual reawakening and devotion to causes such as abolition.

He worked initially with the American Sunday School Union and began defending fugitive slaves.[5] At a time when public opinion in Cincinnati was dominated by Southern business connections, Chase, influenced by local events, including the attack on the press of James G. Birney during the Cincinnati Riots of 1836, associated himself with the anti-slavery movement. Chase was also a member of the literary Semi-Colon Club; its members included Harriet Beecher Stowe and Calvin Stowe.[7] Chase became the leader of the political reformers, as opposed to the Garrisonian abolitionist movement.

For his defense of escaped slaves seized in Ohio under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, Chase was dubbed the Attorney General for Fugitive Slaves[citation needed]. His argument in the case of Jones v. Van Zandt on the constitutionality of fugitive slave laws before the U.S. Supreme Court attracted particular attention. In this and similar cases, the court ruled against him, and John Van Zandt's conviction was upheld. Chase contended that slavery was local, not national, and that it could exist only by virtue of positive state law. He argued that the federal government was not empowered by the Constitution to create slavery anywhere and that when a slave leaves the jurisdiction of a state where slavery is legal, he ceases to be a slave; he continues to be a man and leaves behind the law that made him a slave.

Elected as a Whig to the Cincinnati City Council in 1840[citation needed], Chase left that party the next year. For seven years he was the leader of the Liberty Party in Ohio. He helped balance its idealism with his pragmatic approach and political thought. He was skillful in drafting platforms and addresses, and he prepared the national Liberty platform of 1843 and the Liberty address of 1845. Building the Liberty Party was slow going. By 1848 Chase was leader in the effort to combine the Liberty Party with the Barnburners or Van Buren Democrats of New York to form the Free Soil Party.

The Free Soil movement

Chase drafted the Free-Soil platform[citation needed], and it was chiefly through his influence that Van Buren was their nominee for President in 1848. In 1849, Chase was elected to the U.S Senate from Ohio on the Free Soil ticket. Chase's goal, however, was not to establish a permanent new party organization, but to bring pressure to bear upon Northern Democrats to force them to oppose the extension of slavery.

During his service in the Senate (1849–1855), Chase was an anti-slavery champion. He spoke ably against the Compromise of 1850[citation needed] and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854[citation needed]. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska legislation, and the subsequent violence in Kansas, convinced Chase of the futility of trying to influence the Democrats.[citation needed]

He was a leader in the movement to form a new party opposing the extension of slavery. He tried to unite the anti-slavery Democrats with the dwindling Whig Party, which led to establishment of the Republican Party. "The Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States", written by Chase and Giddings, and published in the New York Times on January 24, 1854, may be regarded as the earliest draft of the Republican party creed.

In 1855 he was elected governor of Ohio[citation needed]. Chase was the first Republican governor of Ohio, serving from 1856 to 1860, where he supported women's rights, public education, and prison reform.

Chase sought the Republican nomination for president in 1860[citation needed]. With the exception of William H. Seward, Chase was the most prominent Republican in the country and had done more against slavery than any other Republican. But he opposed a "protective tariff", favored by most other Republicans, and his record of collaboration with Democrats annoyed many Republicans who were former Whigs.

At the 1860 Republican National Convention, he got 49 votes on the first ballot[citation needed], but he had little support outside Ohio. Abraham Lincoln won the nomination, and Chase supported him.

Chase was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate in 1860[citation needed]. However, three days after taking his seat, he resigned to become Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln. He was a member of the Peace Convention of 1861 held in Washington, D.C., in an effort to prevent the impending war.

Secretary of the Treasury

Chase served as Secretary of the Treasury in President Lincoln's cabinet from 1861 to 1864, during the Civil War. In that period of crisis, there were two great changes in American financial policy, the establishment of a national banking system and the issue of paper currency. The former was Chase's own particular measure. He suggested the idea, worked out the important principles and many of the details, and induced the Congress to approve them. It not only secured an immediate market for government bonds, but also provided a permanent uniform, stable national currency. Chase ensured that the Union could sell debt to pay for the war effort. He worked with Jay Cooke & Company to successfully manage the sale of $500 million in government war bonds (known as 5/20s) in 1862.[8]

The first U.S. federal currency, the greenback demand note, was printed in 1861–1862 during Chase's tenure as Secretary of the Treasury. It was Chase's responsibility to design the notes. In an effort to further his political career, his face appeared on a variety of U.S. paper currency, starting with the $1 bill so that the people would recognize him[citation needed].

On October 10, 1862, Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles wrote that "a scheme for permits, special favors, Treasury agents, and improper management" existed and was arranged by Treasury Secretary Chase for General John A. Dix. The motive of Chase appeared to be for political influence and not for financial gain.[9]

Perhaps Chase's chief defect was an insatiable desire for high office.[10] Throughout his term as Treasury Secretary, Chase exploited his position to build up political support for another run at the Presidency in 1864.

He also tried to pressure Lincoln by repeatedly threatening resignation[citation needed], which he knew would cause Lincoln difficulties with the Radical Republicans.

To honor Chase for introducing the modern system of banknotes, he was depicted on the $10,000 bill printed from 1928 to 1946. Chase was instrumental in placing the phrase "In God We Trust" on United States coins in 1864.[11]

Chief Justice of the United States

In June 1864, Lincoln surprised Chase by accepting his third offer of resignation. The Republican Party had at that point already nominated Lincoln as its presidential candidate and the Treasury was in solid shape, so Lincoln no longer needed to keep Chase in the cabinet to forestall a challenge for the presidential nomination.[12]

But to placate the Radical wing of the party, Lincoln mentioned Chase as a potential Supreme Court nominee. When Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died in October 1864, Lincoln named Chase to replace him. Lincoln issued the nomination on December 6, 1864. Chase was confirmed by the Senate that very day, and immediately received his commission, holding the office from 1864 until his own death in 1873. Chase was a complete change from the pro-slavery Taney; one of Chase's first acts as Chief Justice was to admit John Rock as the first African-American attorney to argue cases before the Supreme Court.[13]

Among his most prominent decisions while on the court were:

- Texas v. White (74 U.S. 700), 1869, in which he asserted that the Constitution provided for a permanent union, composed of indestructible states, while allowing some possibility of divisibility "through revolution, or through consent of the States";[14][15]

- Veazie Banks v. Fenno (75 U.S 533), 1869, upholding banking legislation of the Civil War that imposed a 10% tax on state banknotes; and

- Hepburn v. Griswold (75 U.S. 603), 1870, which declared certain parts of the legal tender acts to be unconstitutional. When the legal tender decision was reversed after the appointment of new Justices, in 1871 and 1872 (Legal Tender Cases, 79 U.S. 457), Chase prepared a very able dissenting opinion.

As Chief Justice, Chase also presided at the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson in 1868.

He gradually drifted back toward his old Democratic allegiance, and made an unsuccessful effort to secure the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1868. He "was passed over because of his stance in favor of voting rights for black men".[13] In 1871, The New Departure policy of Ohio Democrat Clement Vallandigham was endorsed by Chase.[16] He helped found the Liberal Republican Party in 1872, unsuccessfully seeking its presidential nomination.

As early as 1868 Chase concluded that:

Congress was right in not limiting, by its reconstruction acts, the right of suffrage to whites; but wrong in the exclusion from suffrage of certain classes of citizens and all unable to take its prescribed retrospective oath, and wrong also in the establishment of despotic military governments for the States and in authorizing military commissions for the trial of civilians in time of peace. There should have been as little military government as possible; no military commissions; no classes excluded from suffrage; and no oath except one of faithful obedience and support to the Constitution and laws, and of sincere attachment to the constitutional Government of the United States.[17]

Death and legacy

Chase died in New York City in 1873. His remains were interred first in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., and re-interred in October 1886 in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio.[18][19][20] Chase had been an active member of St. Paul Episcopal Cathedral, Cincinnati. Chase's birthplace in New Hampshire was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

The Chase National Bank, a predecessor of Chase Manhattan Bank which is now JPMorgan Chase, was named in his honor, though he had no financial affiliation with it.

In May 1865 Chase was elected a 3rd class companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS). MOLLUS was an organization of Union officers who had served in the Civil War which allowed distinguished civilians who had supported the Union cause to join as 3rd class companions. Chase was one of the first to receive this honor and was assigned MOLLUS insignia number 46.

Chase's portrait is on the $10,000 bill—the largest denomination of U.S. currency to publicly circulate, and an unusually large denomination of U.S. currency—which was printed in 1928 and 1934 series and is no longer in circulation.[21] The bill was last printed in 1945. In 1969 "the Federal Reserve began taking the high-denomination bills out of circulation ... and as of May 30, 2009, there were only 336" remaining.[22]

Chase County, Kansas and Chase City, Virginia are named in his honor. Chasevilles in Florida, Massachusetts, North Carolina (which only lasted from 1868–1871), New York, Ohio, and Tennessee, were also named for him. Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio and Chase Hall, the main barracks and dormitory at the United States Coast Guard Academy, is named for Chase in honor of his service as Secretary of the Treasury, and the United States Coast Guard Cutter Chase (WHEC 718) is named for him, as are Chase Hall at the Harvard Business School and the Salmon P. Chase College of Law at Northern Kentucky University.

The current Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court Chase T. Rogers is genealogically connected to Salmon P. Chase.[citation needed]

Chase was portrayed by the actor Josh Stamberg in the 2013 movie Saving Lincoln.[citation needed]

See also

- Anti-Nebraska Party—political party

- Appeal of the Independent Democrats

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Institutions named for Salmon Chase

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Chase Court

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Semi-Colon Club

- Places named for Salmon Chase

Notes

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2014) |

- ^ "Federal Judicial Center: Salmon Chase". September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Niven, John (1995). Salmon P. Chase. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-504653-3.

- ^ a b c "Salmon P. Chase". Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Blue, Frederick J., Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, 1987, page 8

- ^ a b Ross, Ph.D., Kelley L. "Six Kinds of United States Paper Currency". Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ Morris, William W.; Krieger, E. B., eds. (1921). The Bench and Bar of Cincinnati: Commemorating the Building of the New Court House. Cincinnati: New Court House Publishing Company. p. 16.

It is a coincidence that his county home near Loveland, later came into the possession, for a few years, of Judge Charles J. Hunt, during the years the latter occupied the local Common Pleas Court bench.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis, Jr; and Hollis Robbins. "The Annotated Uncle Tom's Cabin" WW. Norton, p. xxxii

- ^ Geisst, Charles R. (1999). Wall Street. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-511512-3.

- ^ pp. 166, 175, 177, 227, 318, Welles, Gideon. Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, Vol. I, 1861 – March 30, 1864. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911.

- ^ Salmon Portland Chase Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911 Edition, Originally appearing in Volume V05, Page 956

- ^ "History of 'In God We Trust'". US Department of the Treasury. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom. Oxford: 1988. p. 841n. Print.

- ^ a b "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson: Salmon Portland Chase". Impeach-andrewjohnson.com. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ Aleksandar Pavković, Peter Radan, Creating New States: Theory and Practice of Secession, p. 222, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007.

- ^ Texas v. White, 74 U.S. 700 (1868) at Cornell University Law School Supreme Court collection.

- ^ p. 446, Vallandigham, James L. A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham. Baltimore, MD: Turnbull Brothers, 1872.

- ^ J. W. Schuckers, The Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase, (1874). p. 585; letter of May 30, 1993, to August Belmont

- ^ "Chief Justice Chase's Remains". The Evening Star. October 11, 1886. p. 3.

- ^ Template:Wayback Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- ^ See also, Christensen, George A., Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17–41 (February 19, 2008), University of Alabama.

- ^ Old currency values.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (July 24, 2009). "Somebody Call Officer Crumb!:How much cash can a corrupt politician cram into a cereal box?". Slate.com. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

References

- Salmon P. Chase at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

Secondary sources

- Blue, Frederick J. Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics (1987)

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Friedman, Leon. "Salmon P. Chase" in The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Volume 2. (1997) pp 552–67.

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970)

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005) on Lincoln's cabinet.

- Hendrick, Burton J. Lincoln's War Cabinet (1946)

- Niven, John. Salmon P. Chase: A Biography (1995).

- Randall, James G. (1928–1990). "Chase, Salmon Portland". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 4. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 27–34.

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997)

- United States Congress. "Salmon P. Chase (id: C000332)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- J. W. Schuckers, The Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase, (1874).

- William M. Evarts (1874). Eulogy on Chief-Justice Chase.

- Gore Vidal. Lincoln. Salmon Chase is one of the major figures in this extensively researched historical novel.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chase, Salmon Portland". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Primary sources

- Niven, John, et al. eds. ed. The Salmon P. Chase Papers Volume: 2, 1823–57 (1993) vol 1–5 have coverage to 1873

- Niven, John, et al. eds. ed. The Salmon P. Chase Papers Volume: 3, 1858–63 (1993)

- Donald, David ed. Inside Lincoln's Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase (1954)

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 978-1-56802-126-3.

- Frank, John P. (1995). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7910-1377-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505835-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

- Warden, Robert B. (1874). An account of the private life and public services of Salmon Portland Chase. Cincinnati: Wilstach, Baldwin and Co. Authorized biography.

External links

- The Life of Salmon P. Chase, Attorney General of Fugitive Slaves., at WebCitation.org

- The Salmon P. Chase papers, including correspondence and a myriad of biographical materials spanning the years 1820-1884, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Salmon P. Chase at Tulane University Law School.

- Biography at "Mr. Lincoln's White House"

- Biography at "Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Salmon P. Chase"

- Eulogy on Chief-Justice Chase, delivered by William M. Evarts, 1874, at Project Gutenberg

- Biography, Bibliography, and Location of Papers, via U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

- Interview with John Niven on Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, May 28, 1995. at Booknotes

| Offices and distinctions |

|---|

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1808 births

- 1873 deaths

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- American abolitionists

- Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery

- Chief Justices of the United States

- Cincinnati City Council members

- Dartmouth College alumni

- Free Soil Party United States Senators

- Governors of Ohio

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- Ohio Libertyites

- Lincoln Administration cabinet members

- Ohio Free Soilers

- Ohio Liberal Republicans

- Ohio Republicans

- Ohio Whigs

- People from Loveland, Ohio

- People from Sullivan County, New Hampshire

- People from Worthington, Ohio

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Republican Party state governors of the United States

- Republican Party United States Senators

- Union political leaders

- United States federal judges appointed by Abraham Lincoln

- United States presidential candidates, 1860

- United States Secretaries of the Treasury

- United States Senators from Ohio

- Chase Court

- Ohio Democrats

- Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery