Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981: Difference between revisions

Aardvark92 (talk | contribs) m removed duplicate definition of ref "taxtable" |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 5 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

In addition to changes in marginal tax rates, the capital gains tax was reduced from 28% to 20% under ERTA. Afterwards revenue from the capital gains tax increased 50% by 1983 from $12.5 billion in 1980 to over $18 billion in 1983.<ref name=Laffer/> In 1986, revenue from the capital gains tax rose to over $80 billion; following restoration of the rate to 28% from 20% effective 1987, capital gains revenues declined through 1991.<ref name=Laffer/> |

In addition to changes in marginal tax rates, the capital gains tax was reduced from 28% to 20% under ERTA. Afterwards revenue from the capital gains tax increased 50% by 1983 from $12.5 billion in 1980 to over $18 billion in 1983.<ref name=Laffer/> In 1986, revenue from the capital gains tax rose to over $80 billion; following restoration of the rate to 28% from 20% effective 1987, capital gains revenues declined through 1991.<ref name=Laffer/> |

||

Critics claim the tax cuts worsened the deficits in the budget of the United States government. Reagan supporters credit them with helping the 1980s economic expansion<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.presidentreagan.info/expansion.cfm|title=The Reagan Expansion >The Reagan Expansion|accessdate=2009-05-03 |publisher=Ronald Reagan Information Page |

Critics claim the tax cuts worsened the deficits in the budget of the United States government. Reagan supporters credit them with helping the 1980s economic expansion<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.presidentreagan.info/expansion.cfm |title=The Reagan Expansion >The Reagan Expansion |accessdate=2009-05-03 |publisher=Ronald Reagan Information Page |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20081023212358/http://www.presidentreagan.info:80/expansion.cfm |archivedate=October 23, 2008 }}</ref> that eventually lowered the deficits. After peaking in 1986 at $221 billion the deficit fell to $152 billion by 1989.<ref>{{cite book |title=FY 2011 Budget of the United States Government: Historic Tables |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-16-084797-4 |pages=21–22 }}</ref> Supporters of the tax cuts also argue, using the [[Laffer curve]], tax cuts increased economic growth and government revenue. This is hotly disputed—critics contend that, although government income tax receipts ''did'' rise, it was due to economic growth, not tax cuts, and would have risen more if the tax cuts had not occurred; the Office of Tax Analysis estimates that the act lowered federal income tax revenue by 13% relative to where it would have been in the bill's absence.<ref>{{cite journal|author=[http://www.treasury.gov/offices/tax-policy/offices/ota.shtml Office of Tax Analysis]|publisher=[[United States Department of the Treasury]]|title=Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills|date=2003, rev. September 2006|url=http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/tax-analysis/Documents/ota81.pdf|format=PDF|id=Working Paper 81, page 12|accessdate=2009-07-18}}</ref> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 06:12, 2 January 2016

| |

| Long title | An act to amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 to encourage economic growth through reduction of the tax rates for individual taxpayers, acceleration of the capital cost recovery of investment in plant, equipment, and real property, and incentives for savings, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | ERTA |

| Nicknames | Kemp-Roth Tax Cut |

| Enacted by | the 97th United States Congress |

| Effective | August 13, 1981 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 97-34 |

| Statutes at Large | 95 Stat. 172 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (Pub. L. 97–34), also known as the ERTA or "Kemp-Roth Tax Cut", was a federal law enacted in the United States in 1981. It was an act "to amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 to encourage economic growth through reductions in individual income tax rates, the expensing of depreciable property, incentives for small businesses, and incentives for savings, and for other purposes".[1] Included in the act was an across-the-board decrease in the marginal income tax rates in the United States by 23% over three years, with the top rate falling from 70% to 50% and the bottom rate dropping from 14% to 11%. This act slashed estate taxes and trimmed taxes paid by business corporations by $150 billion over a five-year period. Additionally the tax rates were indexed for inflation, though the indexing was delayed until 1985.

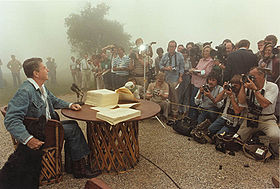

The Act's Republican sponsors, Representative Jack Kemp of New York and Senator William V. Roth, Jr., of Delaware, had hoped for more significant tax cuts, but settled on this bill after a great debate in Congress. It passed Congress on August 4, 1981, and was signed into law on August 13, 1981, by President Ronald Reagan at Rancho del Cielo, his California ranch. This bill and the Tax Reform Act of 1986 are known together as the Reagan tax cuts.[2]

Summary of provisions

The Office of Tax Analysis of the United States Department of the Treasury summarized the tax changes as follows:[3]

- phased-in 23% cut in individual tax rates over 3 years; top rate dropped from 70% to 50%

- accelerated depreciation deductions; replaced depreciation system with ACRS

- indexed individual income tax parameters (beginning in 1985)

- created 10% exclusion on income for two-earner married couples ($3,000 cap)

- phased-in increase in estate tax exemption from $175,625 to $600,000 in 1987

- reduced windfall profit taxes

- allowed all working taxpayers to establish IRAs

- expanded provisions for employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs)

- replaced $200 interest exclusion with 15% net interest exclusion ($900 cap) (begin in 1985)

The accelerated depreciation changes were repealed by Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 and the 15% interest exclusion repealed before it took effect by the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984.

Effect and controversies

The most lasting impact and significant change of the Act was the indexing of the tax code parameters for inflation. Of the nine federal tax laws between 1968 and this Act, six were tax cuts compensating for inflation driven bracket creep.[3] Following enactment in August 1981, the first 5% of the 25% total cuts took place beginning in October of the same year. An additional 10% began in July 1982, followed by a third decrease of 10% beginning in July 1983.[4]

As a result of ERTA and other tax acts in the 1980s, the top 10% were paying 57.2% of total income taxes by 1988—up from 48% in 1981—while the bottom 50% of earners share dropped from 7.5% to 5.7% in the same period.[4] The total share borne by middle income earners of the 50th to 95th percentile decreased from 57.5% to 48.7% between 1981 and 1988.[5] Much of the increase can be attributed to the decrease in capital gains taxes, while the ongoing recession and subsequently high unemployment contributed to stagnation among other income groups until the mid-1980s.[6] Another explanation is any such across the board tax cut removes some from the tax rolls. Those remaining pay a higher percentage of a now smaller tax pie even though they pay less in absolute taxes.

In addition to changes in marginal tax rates, the capital gains tax was reduced from 28% to 20% under ERTA. Afterwards revenue from the capital gains tax increased 50% by 1983 from $12.5 billion in 1980 to over $18 billion in 1983.[4] In 1986, revenue from the capital gains tax rose to over $80 billion; following restoration of the rate to 28% from 20% effective 1987, capital gains revenues declined through 1991.[4]

Critics claim the tax cuts worsened the deficits in the budget of the United States government. Reagan supporters credit them with helping the 1980s economic expansion[7] that eventually lowered the deficits. After peaking in 1986 at $221 billion the deficit fell to $152 billion by 1989.[8] Supporters of the tax cuts also argue, using the Laffer curve, tax cuts increased economic growth and government revenue. This is hotly disputed—critics contend that, although government income tax receipts did rise, it was due to economic growth, not tax cuts, and would have risen more if the tax cuts had not occurred; the Office of Tax Analysis estimates that the act lowered federal income tax revenue by 13% relative to where it would have been in the bill's absence.[9]

References

- ^ Pub. L. 97–34, 95 Stat. 172, enacted August 13, 1981)

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (10 April 2015). "Rand Paul's claim that Reagan's tax cuts produced 'more revenue' and 'tens of millions of jobs'". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ a b Office of Tax Analysis (2003, rev. September 2006). "Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. Working Paper 81, page 12. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|author= - ^ a b c d Arthur Laffer (1 June 2004). "The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future". Retrieved 5 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Joint Economic Committee (1996). "Reagan Tax Cuts: Lessons for Tax Reform". Retrieved 5 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Congressional Budget Office (1986). "Effects of the 1981 Tax Act". Retrieved 5 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Reagan Expansion >The Reagan Expansion". Ronald Reagan Information Page. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ FY 2011 Budget of the United States Government: Historic Tables. 2010. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-16-084797-4.

- ^ Office of Tax Analysis (2003, rev. September 2006). "Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. Working Paper 81, page 12. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|author=

Further reading

- Prasad, Monica, "The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981," Journal of Policy History, 24 (no. 3, 2012), 351–83.