Doorways in the Sand: Difference between revisions

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 25 sources. #IABot |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 0 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 450: | Line 450: | ||

*{{cite encyclopedia |year=1997 |title =Fantasy |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Fantasy]] |publisher=St. Martin's Press |location=New York |trans_title= |journal= |volume= |series= |issue= |page=338 |pages= |at= |chapter= |editor1-first=John |editor1-last=Grant |editor1-link= |language= |format= |id= |isbn=0-312-19869-8 |issn= |oclc= |pmid= |pmc= |bibcode= |doi= |accessdate= |url= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |laysource= |laysummary= |laydate= |quote= |ref= |separator= |postscript= }} |

*{{cite encyclopedia |year=1997 |title =Fantasy |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Fantasy]] |publisher=St. Martin's Press |location=New York |trans_title= |journal= |volume= |series= |issue= |page=338 |pages= |at= |chapter= |editor1-first=John |editor1-last=Grant |editor1-link= |language= |format= |id= |isbn=0-312-19869-8 |issn= |oclc= |pmid= |pmc= |bibcode= |doi= |accessdate= |url= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |laysource= |laysummary= |laydate= |quote= |ref= |separator= |postscript= }} |

||

*{{cite book | last=[[David G. Hartwell|Hartwell, David G.]] | first= | title=Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction | location= | publisher=Tor Books | pages= | year=1996 | isbn=0-312-86235-0}} |

*{{cite book | last=[[David G. Hartwell|Hartwell, David G.]] | first= | title=Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction | location= | publisher=Tor Books | pages= | year=1996 | isbn=0-312-86235-0}} |

||

*{{cite web |url=http://www.sfsignal.com/archives/2009/03/doorways-in-the-sand/ |title=Review: Doorways in the Sand by Roger Zelazny |author=Fred Kiesche |year=2009 |work= |publisher=SF Signal |accessdate=August 7, 2011 |

*{{cite web|1= |url=http://www.sfsignal.com/archives/2009/03/doorways-in-the-sand/ |title=Review: Doorways in the Sand by Roger Zelazny |author=Fred Kiesche |year=2009 |work= |publisher=SF Signal |accessdate=August 7, 2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20090807091603/http://www.sfsignal.com:80/archives/2009/03/doorways-in-the-sand/ |archivedate=August 7, 2009 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last=Krulik | first=Theodore | title=Roger Zelazny | location=New York | publisher=Ungar Publishing | pages= | year=1986 | isbn=0-8044-2490-X}} |

*{{cite book | last=Krulik | first=Theodore | title=Roger Zelazny | location=New York | publisher=Ungar Publishing | pages= | year=1986 | isbn=0-8044-2490-X}} |

||

*{{cite journal |last=[[Jane Langton|Langton, Jane]] |first= |author= |authorlink= |coauthors= |date= |year=1984 |month= |title=The Weak Place in the Cloth |trans_title= |journal=Fantasists on Fantasy |volume= |series= |issue= |page= |pages=163–180 |at= |chapter= |location= |publisher=Avon |editor1-first=Robert H. |editor1-last=Boyer |editor1-link= |language= |format= |id= |isbn=0-380-86553-X |issn= |oclc= |pmid= |pmc= |bibcode= |doi= |accessdate= |url= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |laysource= |laysummary= |laydate= |quote= |ref= |separator= |postscript= }} |

*{{cite journal |last=[[Jane Langton|Langton, Jane]] |first= |author= |authorlink= |coauthors= |date= |year=1984 |month= |title=The Weak Place in the Cloth |trans_title= |journal=Fantasists on Fantasy |volume= |series= |issue= |page= |pages=163–180 |at= |chapter= |location= |publisher=Avon |editor1-first=Robert H. |editor1-last=Boyer |editor1-link= |language= |format= |id= |isbn=0-380-86553-X |issn= |oclc= |pmid= |pmc= |bibcode= |doi= |accessdate= |url= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |laysource= |laysummary= |laydate= |quote= |ref= |separator= |postscript= }} |

||

Revision as of 20:24, 13 February 2016

This article possibly contains original research. (December 2015) |

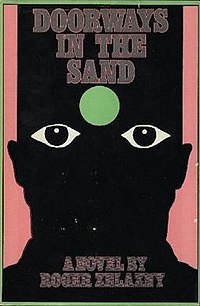

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Roger Zelazny |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Clarke |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Harper & Row |

Publication date | 1976 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 181 |

| ISBN | 0-06-014789-X |

| OCLC | 1863261 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.Z456 Dp3 PS3576.E43 |

Doorways in the Sand is a Nebula- and Hugo-nominated[1][2] science fiction novel with detective fiction and comic elements by Roger Zelazny. It was originally published in serial form in the magazine Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact; the hardcover edition was first published in 1976 and the paperback in 1977. Zelazny wrote the whole story in one draft, no rewrites[3] and it subsequently became one of his own five personal favorites in all his work.[4]

Plot introduction

A galactic confederation of alien civilizations exchanges the star-stone and the Rhennius machine, mysterious alien artifacts, for the Mona Lisa and the British Crown Jewels as part of the process of admitting Earth to its organization. The star-stone is missing, and Fred Cassidy, a perpetual student and acrophile, is the last known person to have seen it. Various criminals, Anglophile zealots, government agents and aliens torture, shoot, beat, trick, chase, terrorize, assault telepathically, stalk, and importune Fred in attempts to get him to tell them the location of the stone. He denies any knowledge of its whereabouts, and decides to make his own investigation. Through the examination of an alien telepath, Fred finds out that the star-stone entered his body through a wound while he was asleep. An alien agent, a representative of the Whillowhim culture, attempts to steal the stone when it is removed from Fred’s body. The Whillowhim seek to limit the power of an alliance of newer, less-developed members of the galactic coalition, and its theft would temporarily stop the entry of Earth to the organization. In a struggle atop the building housing the Rhennius machine, the Whillowhim agent falls to its death. Fred accepts a position as alien cultural expert for the legation of the U.S. to the United Nations. The star-stone, now identified with the name Speicus, is a sentient, telepathic sociological life-form that can gather and analyze information and make reports using Fred as its host.

Principal characters

Fred Cassidy — A building-climbing, wise-cracking, perennial student is the last known person to have seen the missing star-stone, a unique alien crystalline object of unknown origin and function. He denies any knowledge of its whereabouts. Fred receives a generous stipend from his cryogenically-frozen uncle as long as he is a full-time student and has not received an academic degree, which he has put off for 13 years by changing majors repeatedly. Since he is an acrophile, a lover of high places, he occasionally climbs tall buildings.

| The Rhennius machine [was] three jet-black housings set in a line on a circular platform that rotated slowly in a counterclockwise direction, the end units each extruding a shaft - one vertical, one horizontal - about which passed what appeared to be a Moebius strip of a belt almost a meter in width, one strand half running through a tunnel in the curved and striated central unit, which faintly resembled a wide hand cupped as in the act of scratching. |

| — Doorways in the Sand[5] |

The Rhennius machine — An alien device that can transform objects in different ways through its "inversion program." In Doorways it reverses, turns inside out, and incises objects.

Dennis Wexroth — Fred’s latest academic counselor is determined to graduate Fred against his will.

Hal Sidmore — Fred’s best friend and former roommate unknowingly switches a model of the star-stone for the real one in Professor Byler’s laboratory. When he moves out, he leaves the stone in Fred’s apartment.

Paul Byler — A professor of geology and world-renowned crystallographer manufactures replicas of the star-stone for the United Nations. As an extremist Anglophile, Byler is incensed by the loan of the British Crown Jewels to the alien confederation. He hires two thugs, Morton Zeemeister and Jamie Buckler, to plan and help carry out the theft of the star-stone during the delivery of a replica and the real stone to the United Nations.

Charv and Ragma — Alien police officers investigate the theft of the star-stone in order to return it to the United Nations. They assume Fred does not know where it is, but believe the secret of its recovery lies in his subconscious. Ragma is disguised as either a wombat or a dog, while Charv wears a kangaroo suit.

Morton Zeemeister and Jamie Buckler — Sadistic professional criminals are originally employed by Paul Byler and others in his extremist Anglophile group to plan the theft of the star-stone. Ragma and Charv assume that they want the stone for themselves to ransom it back to the United Nations; however, they really work for the Whillowhim.

| I looked down at the pseudostone, semiopaque or semitransparent, depending on one's philosophy and vision, very smooth, shot with milky streaks and red ones. It somewhat resembled a fossil sponge or a seven-limbed branch of coral, polished smooth as glass and tending to glitter about its tips and junctures. Tiny black and yellow flecks were randomly distributed throughout. It was about seven inches long and three across. It felt heavier than it looked. |

| — Doorways in the Sand[6] |

Speicus (the star-stone) — A sentient telepathic alien life form of unknown origin in the shape of a stone acts as a recorder and data processor of sociological information. It needs a symbiote in order to use its nervous system to collect data. Speicus enters Fred’s body through a wound while he is sleeping and convinces him to reverse himself through the Rhennius machine so that it can be fully activated. It can keep its host alive indefinitely.

Doctor M’mrm’mlrr — An alien telepathic analyst practices a technique known as assault therapy. It examines Fred and discovers that Speicus is inside him.

Ted Nadler — A representative of the State Department persuades the university to award Fred a Ph.D in Anthropology and hires Fred as an alien culture expert for the U.S. legation to the United Nations.

The Whillowhim Agent — An alien disguised as a black cat desires the stone in order to keep Earth from joining a coalition of newer, weaker planets whose interests are at odds with the Whillowhim civilization and the massive power block of older, entrenched powers that it belongs to. Fred identifies the Whillowhim with Carroll's Cheshire cat.[7][8] And Speicus calls him a Boojum, a very bad snark.[9]

Ralph Warp — Fred’s partner in the Warp and Woof, a crafts shop, lets Fred crash at his apartment.

Setting

The setting is in the “near-future Earth.”[10] The “near future” is defined in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction as an “imprecise term used to identify novels set just far enough in the future to allow for certain technological or social changes without being so different that it is necessary to explain that society to the reader.”[11]

One character describes the near future in Doorways:

I am especially conscious of the difference between that earlier time and this present. It was a cumulative thing, the change. Space travel, cities under the sea, the advances in medicine—even our first contact with the aliens—all of these things occurred at different times and everything else seemed unchanged when they did. Petty pace.[12]

Add air scooters and flycars and that completes the near future in Doorways.

The action takes place mostly in the United States at an unnamed university in an unnamed city near an unnamed ocean. However, the Australian desert, New York, a small unnamed town in the Alps, and a spacecraft in orbit are other locations in the narrative.

Plot summary

| You are a playboy and a dilettante, with no real desire ever to work, to hold a job, to repay society for suffering your existence. You are an opportunist. You are irresponsible. You are a drone. |

| — Doorways in the Sand[13] |

The will of Fred Cassidy’s cryogenically-frozen uncle provides him with a generous stipend to attend the university until he is awarded an academic degree. By carefully choosing his courses and changing majors, Fred avoids mandatory graduation for thirteen years. He meets with his new academic counselor, Dennis Wexroth, who is infuriated by what he calls Fred’s “dronehood”[14] (See text box.) and threatens to send him off into to the real world by graduating Fred in the coming semester. Fred, however, finds a way to get enough credits in different majors to avoid graduation.

Fred goes to his apartment and finds it ransacked. He examines the apartment, but finds nothing missing. Paul Byler, Fred’s geology teacher comes out of a closet. He slaps Fred around demanding the return of a replica he made of the crystalline star-stone. Byler is a world-renowned expert in crystallography and says he makes copies of the star-stone in order to sell them as novelty items. Fred states that the replica is not in the apartment and maybe his ex-roommate has it. Byler does not believe Fred. After a brief fight Fred escapes through a window to an outside ledge.

Byler visits Hal Sidmore, Fred’s ex-roommate, roughs him up and demands the model of the star-stone. Hal insists he does not have it saying that Fred probably has it in their old apartment. Previously, during a poker game, Byler gives the copy of the star-stone to Hal. However, Hal switches it without Byler's knowledge for what he thinks is a better model, but is in fact the star-stone itself. Arriving home Fred sees a news story on television reporting Byler’s murder and the odd removal of some of his vital organs.

As part of his study plan Fred goes to the desert in Australia to study ancient carvings on a cliff. Zeemeister and Buckler, two professional criminals, arrive and torture Fred for the location of the star-stone. Two alien law officers, Charv and Ragma, disguised as a wombat and a kangaroo respectively save Fred, and they all go into orbit in their spacecraft.

Later, as he comes slowly into consciousness a voice instructs Fred that he should not permit the aliens to take him to another world where they want to telepathically examine his mind for clues to the whereabouts of the star-stone. Fred convinces them that it would be against their alien field regulations to take him without his consent. They return him to Earth.

After being set down on Earth, Fred goes to visit Hal who reports that he receives phone calls from various people trying find Fred. People break into and ransack his apartment several times. And that Ted Nadler, a State Department employee, is looking for him. Finding himself intoxicated Fred stays the night with Hal and hears the voice, now identifying itself as Speicus, that has been talking to him. It tells him to test the inversion program of the alien Rhennius machine and then get intoxicated. It is easier for Speicus to talk to Fred if he is drunk. Fred breaks into the room with the Rhennius machine and, hanging from a rope from the ceiling, puts a penny through the machine three times. The first time Lincoln is looking backwards and the ONE is also backwards. The second time the penny is incised like an intaglio. The third time returns it to normal.

Fred goes bar-crawling to get drunk as Speicus instructs him. He runs into a shady old school adviser named Doctor Mérimée who tells him he is being followed. He joins Mérimée at a party at his apartment, finishes getting drunk, and falls asleep. On waking Fred remembers a communication with Speicus during the night. According to Speicus, reversing himself through the Rhennius machine will put "everything in proper order.”[15]

By subterfuge Fred manages to reverse himself by going through the Rhennius machine. Left is right and vice versa, and letters are read backwards from right to left with the letters turned backwards. He remembers his biochemistry and realizes that this reversal can be dangerous to his health. Meanwhile, Ted Nadler convinces the university to award Fred a Ph.D. in Anthropology. This outrages Fred because he loses his uncle’s stipend and has to get a job.

Fred calls Hal and they agree to meet in a secret place. They begin driving, aimlessly Fred thinks. Hal explains that Zeemeister and Buckler have his wife, Mary, and are demanding the star-stone. He has another replica of the stone from Byler’s lab and is going to trade it for Mary. Fred agrees to go along with the plan against his better judgment. They go to a beach cottage where they find Zeemeister, Buckler, a cat and Mary. Zeemeister declares the stone to be a fake and threatens to pull Mary’s fingernails off until they tell him where the star-stone is. Paul Byler, brought back to life by multiple organ transplants, enters through the back of the cottage with a drawn gun. In the ensuing struggle Buckler shoots Fred in the chest, and he blacks out.

Fred awakens in a hospital. He is alive since his heart was on the right side of his body due to the reversal, and he was shot on the left side where the heart is usually found. Everyone else from the cottage survives with minor injuries. Ted Nadler stops by Fred’s hospital room and offers him a position as alien culture specialist for the U.S. legation to the United Nations. Fred says he’ll think about it.

Nadler explains the history of the star-stone. The United Nations hires Byler as an expert in synthetics and crystals to make a replica for safety purposes. The loan of the British Crown Jewels to the aliens outrages Byler and some of his fanatical Anglophile friends. Byler and an accomplice exchange the real star-stone for a fake one. Byler hires Zeemeister and Buckler in their capacity as professional criminals to assist in the substitution of the stones, but they really want the original for themselves for a ransom, Nadler believes.

While shaving the next morning Fred remembers a smile that remains with him from his night’s dreams. Ted Nadler and Fred travel to New York to meet with a telepath. As Fred enters his hotel room he is seized and raised into the air by the tentacles of an alien telepathic analyst who practices attack therapy. He attempts to reach into Fred’s subconscious for information about the star-stone. He is stunned to discover that the star-stone, Speicus, is inside Fred, having entered his body through a wound while Fred was asleep. Since he was reversed by the Rhennius machine Speicus is now fully functional and should be able to communicate telepathically directly and easily with Fred, but because Fred is now reversed it cannot. On the way to the Rhennius machine to have him reversed back to his original state, Speicus warns Fred about an unknown enemy by saying, “Our Snark is a Boojum.”

In the building housing the Rhennius machine Doctor M’mrm’mlrr, the alien analyst, supervises the removal of the star-stone from Fred’s body. On the wall Fred sees a vision of “massive teeth framed by upward curving lips. . . .Then fading, fading. . . Gone.” Fred looks up and sees a black shape and cries out, “The smile.” Fred chases a telepathic alien disguised as a black cat up to the roof and over girders of the adjacent building. It attacks Fred and falls to its death. During the fight Fred realizes that Zeemeister and Buckler work for the alien agent called a Whillowhim.

Ragma explains that the Whillowhim are one of the oldest, most powerful and entrenched cultures in the galaxy. However, there is an alliance of younger ones that back common policies in conflict with those of the older blocs. The Whillowhim belong to a faction of the galactic coalition that opposes the policies of younger, newer members on major issues. One way to limit the power of the newer, less developed planets is to limit their number. The Whillowhim seeks to steal the star-stone to embarrass Earth and delay its entrance into the coalition of planets thereby weakening the power of the newer planets’ alliance.

Fred’s future is as an alien culture expert for the U.S. legation of the United Nations and as a host for Speicus. Speicus will use Fred’s nervous system as well as his broad knowledge of many subjects to gather information and process it as a kind of sociological computer. It can produce uniquely accurate and useful reports on anything they study together. In the end, Fred sees a beach with doorways leading to unique experiences in exotic places throughout the galaxy.

Reception

Some reviewers expressed disappointment not only in Doorways, but in Zelazny’s previous recent work as well. Praise was unenthusiastic.

Spider Robinson in Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine stated that Zelazny's initial works gave the science fiction world hope that he would write “muscular adventure in the language of the poet, uniting drama and beauty,” but he had failed. Nonetheless, he described Doorways as “A cracking good yarn, thin on calories but delicious.”[16]

Richard E. Geis in Science Fiction Review wrote that “at the end I was left vaguely unsatisfied,” but the novel had “Zelazny magic; that indefinable stylistic touch that makes him extremely readable.”[17]

Locus magazine’s Susan Wood wondered if Zelazny’s “promise would ever be fulfilled.” She described Doorways as “a well-written adventure,” and “fast enough, interesting enough, to carry any bedtime reader through arbitrary plotting to midnight and the loose-ends-tied-up conclusion.”[18]

Having read seven of Zelazny’s most recent books in one month, Richard Cowper in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction lamented the loss of Zelazny as science fiction’s prose-poet:

Hope deferred maketh the heart sick. As I progressed from one improbable fantasy to the next, I winced at what I felt to be the squandering of a rare and remarkable talent and felt a growing sense of dismay—in truth as much for Zelazny as for myself. There are felicities of style, of invention, of learning or wit, which stamp it as being his alone. The energy is still there, together with the desire to experiment, but the early promise remains unfulfilled. He has yet to give us that major work.[19]

Nonetheless, he rated Doorways as "definitely superior."

On the other hand, Algis Budrys in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction wrote that Doorways “is one of the first hopeful signs from this author in some time” and “a return toward the power Zelazny once displayed, plus a maturation that runs deeper than witticism.” He called Doorways a “rather good novel.”[20]

Doorways in the Sand has had five English editions with separate ISBN numbers, the last in 1991, and has been translated into German, Bulgarian, Dutch, Russian, Hebrew, Japanese, French, Italian, and Polish.

Literary features

Genres

Zelazny mixes other genres into his science fiction and fantasy works. In his fantasy Amber series, Krulik identifies space opera, mystery and fairy tale elements in Nine Princes in Amber; tales of knighthood and allegory in The Guns of Avalon; drawing-room mystery in Sign of the Unicorn; and, as in Doorways, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in The Courts of Chaos.[21]

Doorways is a science fiction novel with mystery and comic elements that evokes[22] and offers homage[23] to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass, and The Hunting of the Snark; and to notes by Martin Gardner in The Annotated Alice.

Science fiction

While it is difficult to define “science fiction,” some features often cited include:

- Science or pseudoscience orientation to the story

- The future

- Space near earth

- Space travel[24]

- Aliens, especially visits by aliens

- Visiting other worlds

- Different political systems[25]

- New inventions and technologies[26]

Many of the hallmarks of science fiction are part of Doorways: The setting is Earth in the near future. Aliens come in space ships giving the Rhennius machine and the star-stone. Fred leaves Earth in a space ship to orbit the globe. In the end Fred and the star-stone are on an alien world.

Detective fiction

| As I grinned and grimaced in the glass, I had thought of the only fragment of the night's dreaming that remained with me. There was this smile. Whose? I did not know. It was just a smile, somewhere a little over the line from the place where things begin to make sense. It remained with me, though, flickering on and off like a fluorescent tube about to call it quits . . . |

| — Doorways in the Sand[27] |

Doorways is also detective fiction. Some characteristics of detective stories are:

- Detectives, amateur and police

- A crime or mystery

- An investigation

- Clues

- A solution to the crime or mystery

- Exposure of the guilty parties

- Hardboiled detective language (See text box.)

In Doorways there are two mysteries: the location of the star-stone and what it can do. Fred investigates because everybody keeps after him thinking that he knows where it is. Two alien law officers run a parallel investigation. Some clues are offered such as the fading smile and Speicus’ communications. The star-stone and its functions are discovered. The evil party, the Whillowhim, and its goals are revealed. Its death ends the detective story.

Fantasy

While Doorways is clearly not a fantasy novel, it is necessary to understand the differences between fantasy and science fiction since Zelazny converts elements of one into elements of the other. Some traits of fantasy are:

- Inspiration from mythology and folklore[28]

- Self-contained world different from ours.

- Consistent rules of magic.[29]

- Fantastic devices[30]

- Supernatural elements

Doorways shares none of these characteristics.

Comedy

Zelazny laces many of his works with humor, but with Doorways he set out to write a truly comedic novel.[31]

Krulik writes:

An important reason for Doorways' success is Zelazny’s humor. This novel is probably his most wildly comic work, combining the kind of verbal humor he is known for with ridiculous situations that border on the absurd, and secondary characters whose posings and behavior give an antic flavor to the comedy.[32]

An example of the absurd is the name Zelazny gives to the cryonics facility that stores Fred's uncle: "Bide-A-Wee."[33]

Here is an example of wordplay between Fred and his best friend, Hal Sidmore:

"Enter, pray."

"In which order?"

O bless this house, by all means, first. It could use a little grace."

"Bless," I said, stepping in.[34]

Here he satirizes some silly practices of bureaucracies with some double-talk. This is a series of conversations between Fred and the alien cop, Ragma:

"Indicated by whom?" I asked.

"I am not permitted to say"

He cut short a snappy rejoinder by pouring more water down my throat. Choking and considering, I modified it to "This is ridiculous!"[35]

"How? How did you know?"

"Sorry," Ragma said. "That's another."

"Another what?"

"Thing we are not permitted to say."

"Who does your permitting and forbidding?"

"That's another."[36]

"However, since it is all contingent on the results of the analysis, it would be an exercise in redundancy to detail the various hypotheses which may have to be discarded."

"In other words, you are not going to tell me?"

"That pretty well sums it up."[37]

In Doorways as in The Courts of Chaos the evocations of and homage to Lewis Carroll's works provide many of the gags and mad humor. Lewis Carroll is mentioned by name in the novel.[38] Here are some of the many allusions to Alice in Doorways:

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Doorways begin on warm May afternoons. On page one of Doorways Fred says, “I glanced at my watch. It indicated that I was late for my appointment.”[39] Zelazny relates Fred to the White Rabbit, who on page one of Alice says, “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late.”[40] He then takes out his pocket watch and looks at it. Many other Doorways characters are parallel to Alice characters:

- Morton Zeemeister and Jamie Buckler are sadistic versions of the Walrus and the Carpenter. Zeemeister is described as “a little under six feet—but heavily built and beginning work on a paunch.” He produces “a surprisingly delicate handkerchief.”[41] Alice’s Walrus is tall, corpulent and dabs his eyes with a prettily decorated handkerchief in Tenniel’s drawing.[42] The Walrus and the Carpenter mercilessly consume the oysters that they have lured out of their beds, and Zeemeister and Buckler torture Fred at length and threaten to pull out Mary’s fingernails.

- Ralph Warp, Fred’s partner in the crafts store, Warp and Woof, is described as having bad posture and lots of dark hair. He teaches basket weaving and moves his furniture around so often that it's always confusing to Fred.[43] Chapter 5 of Through the Looking Glass is entitled Wool and Water. Tenniel’s drawing shows that the sheep in the shop has dark wool and no shoulders to speak of, and is knitting. Whenever Alice tries to look directly at an item on a shelf, it moves.[44]

- Throughout the story Fred is haunted by a phantom smile, perhaps telepathic touches of the Whillowhim, his evil alien nemesis. Before his fight with the Whillowhim who is disguised as a cat he sees on the wall of the building housing the Rhennius machine: "massive teeth framed by upward curving lips on the far wall. Then fading, fading . . . Gone.”[9] In Alice the Cheshire-Puss slowly disappears beginning with its tail and ending with its grin full of teeth hanging in the air for a few moments before disappearing.[45]

Zelazny refers to well-known Carrollian quotations throughout the novel:

- “Curiouser and curiouser.”[46][47]

- “Our snark is a Boojum.”[48]

- Zelazny lampoons Carroll’s Jabberwocky: “Behold the riant anthropoid, beware its crooked thumbs!"[49] The corresponding lines of Jabberwocky are “Beware the Jabberwock, my son!/The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!"[50]

Other references to Alice include:

- Zelazny writes a nonsense poem that uses the non-Euclidean geometry of Nikolai Lobachevsky and Bernhard Riemann to extol the curved features of the female form.[51]

- One device used in Doorways is reversed writing, a result of Fred’s reversal through the Rhennius machine. Carroll uses mirror writing for the first stanza of Jabberwocky before printing the whole poem correctly.[50] After his inversion, Fred reads all writing backwards, most notably the writing on his Ph.D. diploma.[52]

- Alice talks to many different creatures in her walks through Wonderland. Fred talks to aliens disguised as a kangaroo, a cat, a dog, a wombat and a donkey. The kangaroo, a cat, and a (non-speaking) dog are found in Alice. Gardner suggests that Alice's dormouse may have been modeled after a real wombat.[53] The donkey is absent.

Narrative

First person

Doorways is mostly narrated in the first person by its protagonist, Fred Cassidy. However, in the last chapter Speicus, the sentient sociological computer, takes up the story.

One reviewer has been critical of Zelazny’s use of the first-person narrative technique: “It’s a difficult form to control, since the narrator has to be used to tell his . . . own story, give us a sense of his own personality, suggest enough of outside events and responses to give another perspective on that character. Over and over in his work, Zelazny only accomplishes the first of these tasks.”[18]

Structure

Zelazny experimented with a of number of narrative techniques.[54] Doorways uses a flashforward technique which can be confused with flashback. Zelazny himself used the term flashback:

Once I knew what the story was to be, I ran it, a piece at a time, through a flashback machine, using the suspense-heightening flashback trick so frequently and predictably that the practice intentionally parodied the device itself.[55]

Zelazny divided most chapters into two to five sections, placed the most mysterious or exciting part first, then arranged the other pieces of the narrative out of sequence. His use of this method had a mixed reception.

Susan Wood in Locus magazine wrote, “Used sparingly, it could effectively create suspense. Used in each chapter, however, it becomes monotonous and mannered, interfering with the flow.”[18] Another critic stated, “It seems like grandstanding, and it gets in the way of my enjoyment of the story. . . . It makes it easy to identify with a protagonist who doesn’t know what’s going on either, but it’s irritating.”[56] However, Fred Kiesche of SF Signal felt that “The magic of the plot [is] where you’re never sure of what exactly is going on.”[57]

Style

Prose

Zelazny has been repeatedly referred to as a prose-poet.[58][59][60] However, there does not appear to be agreement about the true nature of his prose.

Geis writes that Doorways "is written with the Zelazny magic; that indefinable stylistic touch that makes him extremely readable."[17] The prose in Doorways has been variously described as "straight-forward,"[20] "well-written and fast paced," "colloquial and functional."[18]

Cowper writes that Zelazny

has fashioned for himself a style which . . . is designed to dazzle. Seen at its best, . . . it is allusive, economical, picturesque and witty [and] highly metaphorical. There are felicities of style, of invention of learning or wit, which stamp it as being his own.[61]

Sturgeon praises him for his "texture, cadence and pace."[62]

Lindskold asserts that "In the final analysis . . . unlike a poet, a fiction writer must emphasize content and character over form, image, and structure."[58]

Poetry

| Epiphany in Black & Light, Scenario in Green, Gold, Purple & Gray . . . There is a man. He is climbing in the dusky days end air, climbing the high Tower of Cheslerei in a place called Ardel beside a sea with a name he cannot quite pronounce as yet. The sea is as dark as the juice of grapes, bubbling a Chianti and chiaroscuro fermentation of the light of distant stars and the best rays of Canis Vibesper, its own primary, now but slightly beneath the horizon, rousing another continent, pursued by the breezes that depart the inland fields to weave their courses among the interconnected balconies, towers, walls and walkways of the city, bearing the smells of the warm land toward its older, colder companion . . . |

| — Doorways in the Sand[63] |

Lindskold adds as elements of poetic diction alliteration, internal rhyme, and metaphor to form, image, and structure.[64]

In Doorways, with the exception of Speicus' narration in the last chapter (See text box.), Zelazny utilizes the language of poetry to characterize the mental states of falling asleep or into a stupor, or awakening from such states.

In the Australian desert, bound and being tortured by Zeemeister and Buckler, Fred evokes losing consciousness: "Sunflash, some splash. Darkle. Stardance. Phaeton's solid gold Cadillac crashed where there was no ear to hear, lay burning, flickered, went out. Like me."[65]

In Charv and Ragma's space vehicle Fred comes out of unconsciousness with Speicus speaking to him in his head:

Thus, thus, so and thus: awakening as a thing of textures and shadings: advancing and retreating along a scale of soft/dark, smooth/shadow, slick/bright: all else displaced and translated to this: The colors, sounds and balances a function of these two.

Advance to hard and very bright. Fall back to soft and black . . .

"Do you hear me, Fred?"—the twilight velvet.

"Yes" —my glowing scales.

"Better, better, better . . ."

"What/who?"

"Closer, closer, that not a sound betray . . ."[66]

On a long bus ride Fred nods off drunkenly: "Drifting drowsy across the countryside, I paraded my troubles through the streets of my mind, poking occasional thoughts between the bars of their cages, hearing the clowns beat drums in my temples."[67]

Again with Speicus in his head, Fred describes going to sleep and dreaming:

Some upwelling in the dark fishbowl atop the spine later splashed dreams, patterns memory-resistant as a swirl of noctilucae, across consciousness' thin, transparent rim, save for the kinesthetic/synesthetic DO YOU FEEL ME LED? which must have lasted a time-less time longer than the rest, for later, much later, morning's third coffee touched it to a penny's worth of spin, of color.[68]

Major themes

Immortality

More than half of Zelazny’s novels have characters who are immortal or nearly immortal.[69] Zelazny believed living a long life would make people have great intellectual and perceptual faculties and would produce a good sense of humor.[70]

Immortality for Zelazny generally meant an immortal can be killed like any other person, but not from old age. A long life according to Zelazny would not cause ennui, but rather curiosity, changing and maturing, growing and learning, and lead to knowledge, culture and satisfying experiences.[71][72] According to Samuel R. Delany, Zelazny believed that “Given all eternity to live, each experience becomes a jewel in the jewel-clutter of life; each moment becomes infinitely fascinating because there is so much more to relate it to."[73]

In Doorways Fred achieves near immortality as a host for Speicus. In the hospital after being shot all of Fred’s injuries heal speedily. Later Speicus tells Fred that he is able to repair his body indefinitely.[74]

Education

For Zelazny one of the attractions of immortality was that an immortal could continue to learn forever. And Zelazny had a lifelong love of learning.

In college he often audited courses he found interesting in addition to his regular plan of studies. In 1971 he designed an evolving curriculum of studies for himself that he would pursue for the rest of his life. One of his concerns was to obtain greater amounts of diverse information that would make him a better writer. These studies included cultural and physical geography, ecology, education, history, biography, literature, and other sciences and humanities. A principle of his studies was the notion that we create ourselves, and learning is part of that process.[75]

In Doorways Fred has a similar program of studies, not just motivated by a desire to learn, but also to keep money flowing from his cryogenically-frozen uncle’s trust fund.

During his thirteen years of studies at the university he takes just enough courses in each discipline to not receive a degree according to the mandatory departmental graduation requirements, making him very broadly-educated.

Literary revisionism

Zelazny wrote science fiction and fantasy, receiving Hugo and Nebula awards in both genres. However, he sometimes took elements from one and converted them to the other. Krulik writes: “This imposition of science upon magic, and its reverse, forms a fascinating conflict that is apparent in his writings.”[76] In Doorways Zelazny changes three fantasy elements into science fiction elements.

Jewels with supernatural properties are a staple in fantasy. In Zelazny’s Amber series the Jewel of Judgment plays a decisive role in the plot. In Jack of Shadows, Jack is imprisoned in a jewel that is worn around the neck by another character, the Lord of Bats.

Zelazny takes the jewel fantasy motif and revises it into the star-stone in Doorways. Instead of having magical qualities, the star-stone is described in the vocabulary of science:

To function properly, [Speicus] requires a host built along our lines. It exists then as a symbiote within that creature, obtaining data by means of that being’s nervous system as it goes about its business. It operates on this material as something of a sociological computer. In return for this, it keeps its host in good repair indefinitely. On request, it provides analyses of anything it has encountered directly or peripherally, along with reliability figures, unbiased because it is uniquely alien to all life forms, yet creature-oriented because of the nature of the input mechanism. It prefers a mobile host with a fact-filled head.[77]

Another fantasy element that Zelazny converts to science fiction is Alice’s looking glass. Looking through her mirror Alice observes that objects are the same as in her drawing room, but “. . . the things go the other way.”[78] A book held up to a mirror in the right hand has reversed writing in the mirror and the book is in the left hand of the mirror image of the person on the other side of the looking glass. The mirror reverses the image from one side to the other.

In Doorways Zelazny reimagines Alice’s looking glass as the Rhennius machine, the device given to man by the aliens that reverses objects into their mirror images. At Speicus’ urging Fred puts himself through the machine. The left side of his body is on the right and vice versa. Also left becomes right and vice versa, and writing is backwards for Fred.

And finally, Zelazny reenvisions another Alice artifact in Fred's mind. In Alice the White Rabbit goes down the rabbit hole which leads to Wonderland. While Fred is being tortured in the Australian desert, he looks around for a doorway in the sand, a passageway that will take him out of his surreal nightmare back to his normal world.

However, at the end of Doorways Zelazny revises the rabbit hole again. Fred imagines all the doorways in the sand that will lead to all the exotic places he and Speicus will visit and experiences that they will have throughout the galaxy: “Behind me the beach was suddenly full of doorways, and I thought of ladies, tigers, shoes, ships, sealing wax. . . .”[79][80]

Protagonists

Zelazny's literary biographers have disagreed over the basic profile of his protagonists. Krulik writes:

More than most writers, Zelazny persists in reworking a persona composed of a single literary vision. This vision is the unraveling of a complex personality with special abilities, intelligent, cultured, experienced in many areas, but who is fallible, needing emotional maturity, and who candidly reflects upon the losses in his life. This complex persona cuts across all of Zelazny's writings. . . .[81]

Fred Cassidy does not appear to be a complex personality, but he has two special abilities: he climbs buildings well because of his acrophlia and he has an extraordinary thirteen-year education in all the departments of the university. He is intelligent, cultured and experienced due to his education only, fallible, needs emotional maturity and experience, but does not dwell on his life's struggles very much.

Lindskold believes that Krulik's view oversimplifies Zelazny's protagonists and proposes four classifications: heroic, morally ambivalent "heroes," more villain than hero, and ordinary people.[82] She classifies Fred as an ordinary person "who is forced into action by extraordinary circumstances."[83]

Maturation

Zelazny portrays Fred as a hard partyer who sometimes drinks too much, a gambler, and a good student who wants to study but not get a degree. Professor Wexroth, Fred's academic adviser, calls Fred a playboy and an irresponsible dilettante with no desire to work or repay society.[84]

With regard to the maturation of his protagonists, Zelazny writes: "I am interested in characters in a state of transformation. I feel it would be wrong to write a book where the character proceeds through all of the action and winds up pretty much the same at the end as he was in the beginning, just having an adventure. He has to be changed by the things that take place."[85]

In this vein Krulik observes: "Growth of any fictional character depends on what he learns about himself during the course of a work, and how he changes as a result of this knowledge. This is a basic tenet of all literature and certainly one that Zelazny subscribes to."[86]

In Doorways Fred goes through a series of life-changing experiences. He is stalked, slapped around, beaten, chased, threatened, terrorized, tortured and shot. He fears mutilation and contemplates his own death.[87]

In the end he accepts a responsible position as an alien culture specialist for the U.S. legation to the United Nations. And he agrees to serve as host for Speicus and travel the galaxy studying various cultures. His old mentor, Professor Dobson, urges him to learn something in his job, if only humility. Using Fred's acrophilia as a metaphor, Dobson tells him to "Keep climbing. That is all. Keep climbing, and then go a little higher."[88]

Allusions

Zelazny makes many obscure literary and scientific allusions. His critics disagree over the effect these references might have on readers.

Theordore Sturgeon in his introduction to Four For Tomorrow calls Zelazny's more obscure allusions "furniture." Some allusions, he writes "can keep a reader from his speedy progress from here to there, and that his furniture should be placed outside the traffic pattern."[89]

Krulik takes the view that "It's a risky business, but Zelazny has enormous stylistic power, and his strong characterizations are usually able to draw back the reader to the written word after chewing momentarily on the morsel given to him for thought."[90]

Lindskold feels that in stories "the reader who is uninterested in delving into the subtext can still enjoy the story simply for the plot alone."[91]

Below are a few of the literary and scientific allusions in Doorways:

- A quotation from Pulitzer Prize-winning poet John Berryman's The Dream Songs is written in reversed writing: "I stalk my mirror down this corridor/my pieces litter. . . ."[92]

- Zelazny refers to Flatland and Sphereland, books which discuss applications in Euclidean (flat) and non-Euclidean (sphere) geometry.[93]

| Lobachevsky alone has looked on Beauty bare. She curves in here, she curves in here. She curves out there. The world is curves, I’ve heard it said, |

| — Doorways in the Sand[51] |

- Along the same lines, Zelazny writes a nonsense poem, Lobachevsky alone has looked on beauty bare, evoking the non-Euclidean geometry of Lobachevsky and Riemann to describe the curves of the female anatomy.[51] This is a takeoff on Euclid alone has looked on beauty bare, a 1922 poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay.

- See above under "Literary revision" and "Comedy" the many tributes to Alice.

- Zelazny refers in passing to B. Traven, a mysterious German novelist who lived most of his life in Mexico. He is known for his novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.[94]

- A "brace of roods" does not describe two crosses in Doorways, but rather a double cross.[95]

- Fred says he does not want to remain a "Spiegelmensch" (a mirror man) very long. This is a reference to Franz Werfel's 1921 play whose title is translated as Mirror Man. The play is about a pair of doppelgangers, one good, one evil.[67]

- Hilbert space is a mathematical concept that is about the conversion of 2-dimensional space to spaces with more than two or three dimensions.[94]

- After Fred gets shot the next chapter does not begin in the hospital showing that he is alive, but rather is preceded by two pages discussing Charles William Eliot, President of Harvard University and his impact on the modern liberal arts curriculum, and the pseudosexual behavior of an African wasp and an orchid.[96]

- When going to sleep Fred says, "'Let there be an end to thought. Thus do I refute Descartes.' I sprawled, not a cogito or a sum to my name." This refers to Descartes' famous dictum "Cogito ergo sum," "I think therefore I am."[97]

Publication history

- (1975 June) Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact. Conde Nast Publishers Inc. pp. 180. Part 1 of 3. Digest, magazine. English.

- (1975 July) Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact. Conde Nast Publishers Inc. pp. 180. Part 2 of 3. Digest, magazine. English.

- (1975 August) Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact. Conde Nast Publishers Inc. pp. 180. Part 3 of 3. Digest, magazine. English.

- (1976) New York: Harper and Row. pp. 181. Hardcover. English. ISBN 0-06-014789-X

- (1976) Harper and Row/Science Fiction Book Club #2869. pp. 181. Hardcover. English ISBN 1299478670

- (1977) New York: Avon Books. pp. 189. Paperback. English. ISBN 0-380-00949-8

- (1977) London: W.H. Allen/Virgin Books. pp. 185. Cloth. English. ISBN 0-491-02022-8

- (1977) Stersteen. Het Spectrum. pp. 192. Paperback. Dutch, Flemish. ISBN 90-274-0929-3

- (1978) Star Books/W. H. Allen. pp. 185. Paperback. English. ISBN 0-352-39724-1

- (1981) Stempel über Fußschnitt. Moewig, Rastatt. Paperback. German. ISBN 3-8118-3525-4

- (1981) Suna no naka no tobira. (trans. Hisashi Kuromaru). Hardcover. Japanese. OCLC 672582333

- (1984) Le rocce dell'Impero. Editrice Nord. Paperback. Italian. ISBN 9788842901457

- (1985) Tore in der Wüste. Pabel-Moewig Verlag Kg. Broschiert. German. ISBN 3-8118-3525-4

- (1991) New York: HarperPaperbacks. Paperback. English. ISBN 0-06-100328-X

- (1993) Bramy w piasku. Warszawa: "Alkazar". Polish. ISBN 83-85784-17-9

- (1998) La pierre des etoiles. Denoel (Editions). pp. 192. Mass Market Paperback. French. ISBN 2-207-24778-3

- (1998) La pierre des etoiles. Denoel (Editions). pp. 192. Poche. French. ISBN 2-207-30243-1

- (1998) Пясъчни врати. Юлиян Стойнов (Translator). Камея. pp. 208. Paperback. Bulgarian. ISBN 954-8340-36-3

- (1999) Dveri v peske. Moskva: Ėksmo-Press. Russian.

- (2003) Miftaḥim ba-ḥol. Tel Aviv : ʻAm ʻoved. Hebrew. ISBN 965-13-1656-X

- (2004) Dveri v peske. Moskva: Ėksmo. Russian. ISBN 5-04-009653-4

- (2006) Dveri v peske. Moskva: Ėksmo. Russian. ISBN 5-699-17339-0

Awards and nominations

- Nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1975.[1]

- Nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1976.[2]

Notes

- ^ a b "1975 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2011-06-23. Cite error: The named reference "WWE-1975" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "1976 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20080216071849/zelazny.corrupt.net/amberever.html

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20080216071439/http://zelazny.corrupt.net/phlog44rzint.txt

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 51

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 112

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 64,

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 170

- ^ a b Zelazny 1976, p. 154

- ^ Wood, January 1976, p. 7

- ^ D’Ammassa 2005, p. 436

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 21

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p.7

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 9

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 79

- ^ Robinson October 1976, p. 131

- ^ a b Geis February 1976, p. 23

- ^ a b c d Wood January 1976, p. 5

- ^ Cowper March 1977, pp. 145-147

- ^ a b Budrys July 1977, p. 5

- ^ Krulik 1986, pp. 103-105

- ^ Krulik March 1977, p. 144

- ^ Krulik March 1977, p. 146

- ^ Sterling 2008, p.1

- ^ Hartwell 1996, pp. 109-131

- ^ Card 1990, p. 17

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p.136

- ^ Grant 1997, p. 338

- ^ Langton 1984, pp. 163-180

- ^ Waggoner 1978, p. 10

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p.9

- ^ Krulik, 1986 p. 65

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 8

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 56

- ^ Zelazny 1976. p. 42

- ^ Zelazny 1976. p. 43

- ^ Zelazny 1976. p. 145

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 161

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 1

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 25

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 30

- ^ Carroll 1871, p. 237

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 100

- ^ Carroll 1871, p. 252

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 90

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 35

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 52

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 152

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 166

- ^ a b Carroll 1871, p. 191

- ^ a b c Zelazny 1976, p. 40

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 86

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 95

- ^ Kiesche 2009, 9.1

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p. 9,

- ^ Walton 2009, p. 1

- ^ Kiesche 2009, p.1.

- ^ a b Lindskold 1993, p. 76

- ^ Cowper March 1977, p.143

- ^ Sturgeon 1967, p. 5

- ^ Cowper March 1977, pp. 146-147

- ^ Sturgeon 1967, p. 7

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p 112

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p.78

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 27

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 45

- ^ a b Zelazny 1976, p. 97

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 26

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p. 99

- ^ Krulik 1986, p. 11

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p. 90

- ^ Krulik 1986, p. 31

- ^ Delany 1977, pp. 181-182

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 181

- ^ Lindskold 1993, pp. 19-20

- ^ Krulik 1986, p. 114

- ^ Zelazny 1976, pp. 176-177

- ^ Carroll 1871, p. 181

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p.174

- ^ Carroll 1865, p. 235

- ^ Krulik 1986, pp. 23-24

- ^ Lindskold 1993, pp. 94-119

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p. 113

- ^ Zelazny 1976, pp. 24-27

- ^ Krulik 1986, pp. 64-65

- ^ Krulik 1986, p. 55-56

- ^ Zelazny 1976, pp. 32-33

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 179

- ^ Sturgeon 1967, pp. 9-10

- ^ Krulik 1986, p. 10

- ^ Lindskold 1993, p.76

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 107

- ^ Zelazny 1976, pp. 102-103

- ^ a b Zelazny 1976, p. 180

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 133

- ^ Zelazny 1976, pp. 118-119

- ^ Zelazny 1976, p. 62

References

- Budrys, Algis (July 1977). "Books". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

- Card, Orson Scott (1990). How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Writer’s Digest Books. ISBN 0-89879-416-1.

- Carroll, Lewis (1865). Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. London: Macmillan. In Gardner, Martin (1960). The Annotated Alice. New York: Meridian

- Carroll, Lewis (1871). Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. London: Macmillan. In Gardner, Martin (1960). The Annotated Alice. New York: Meridian.

- Cowper, Richard (March 1977). "A Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose. . .In Search of Roger Zelazny". Foundation - The International Review of Science Fiction. 11 and 12. The Science Fiction Foundation: 145–147.

- D'Ammassa, Don (2005). "Roger Zelazny". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: Facts On File, Inc. pp. 432–434. ISBN 0-8160-5924-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - Delany, Samuel R. (1977). The Jewel-Hinged Jaw. New York: Berkeley Books. ISBN 978-0-8195-7246-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gardener, Martin (1960). The Annotated Alice. New York: Meridian. ISBN 0-452-01041-1.

- Geis, Richard E. (February 1976). "Prozine Notes". Science Fiction Review. 5.

- Grant, John, ed. (1997). "Fantasy". The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 338. ISBN 0-312-19869-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - Hartwell, David G. (1996). Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction. Tor Books. ISBN 0-312-86235-0.

- Fred Kiesche (2009). "Review: Doorways in the Sand by Roger Zelazny". SF Signal. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Krulik, Theodore (1986). Roger Zelazny. New York: Ungar Publishing. ISBN 0-8044-2490-X.

- Langton, Jane (1984). Boyer, Robert H. (ed.). "The Weak Place in the Cloth". Fantasists on Fantasy. Avon: 163–180. ISBN 0-380-86553-X.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|coauthors=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|laysummary=,|laysource=, and|month=(help) - Lindskold, Jane M. (1993). Roger Zelazny. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-3953-X.

- Robinson, Spider (October 1976). "Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction.

- Sterling, Bruce. "Science Fiction". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - Sturgeon, Theodore (1967). "Introduction".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) In Zelazny, Roger (1967). Four for Tomorrow. New York: Ace. ISBN 9780824014445.{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Waggoner, Diana (1978). The Hills of Faraway: A Guide to Fantasy. New York: Atheneum. p. 10. ISBN 0-689-10846-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Walton, Jo (2009). "Science Fiction and Fantasy Books". World Without End. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- Wood, Susan (January 1976). "Locus Looks at Books". Locus. 9.

- Zelazny, Roger (1976). Doorways in the Sand. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-014789-X.

Other sources

- Kovacs, Christopher S. The Ides of Octember: A Pictorial Bibliography of Roger Zelazny. Boston: NESFA Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-886778-92-4

- Levack, Daniel J. H. (1983). Amber Dreams: A Roger Zelazny Bibliography. San Francisco: Underwood/Miller. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-934438-39-0.

- Sanders, Joseph (1980). Roger Zelazny: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography. Boston: G. K. Hall and Co. ISBN 9780816180813.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Stephens, Christopher P. (1991). A Checklist of Roger Zelazny. New York: Ultramarine Press. ISBN 9780893661663.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Yoke, Carl (1979). Roger Zelazny: Starmont Reader’s Guide 2. West Linn, Oregon: Starmont House. ISBN 9780916732042.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Yoke, Carl (1979). Roger Zelazny and Andre Norton: Proponents of Individualism. Columbus, Ohio: State University of Ohio.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Alex Heatley (October 5, 2011). "Interview with Roger Zelazny". Phlogiston 44. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Author Information: Roger Zelazny". Internet Book List. 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "Bibliography: Doorways in the Sand". Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "Book Information: Doorways in the Sand". Internet Book List. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "Doorways in the Sand". Open Library. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "Doorways in the Sand". Worldcat. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- "Exhibitions/Science Fiction Hall of Fame: Roger Zelazny". EMP Museum. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Roger Zelazny". Locus Index to SF Awards. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Roger Zelazny – Summary Bibliography". Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. Retrieved August 7, 2011.