Sexagenary cycle: Difference between revisions

Fixing link from Mawangdui Han tombs to Mawangdui |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.7.1) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

year of the reign of [[Qin Shi Huang]] (秦始皇), 246 BC, is applied to the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term (51 of 60, 甲寅—''jiǎ - yín'') corresponding to that year.<ref>Kalinowski (1998), pp. 135–148, and fig. 3; Smith (2011), p. 29.</ref> Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the [[Western Han Dynasty]] (202 BC - 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since:<ref>Smith (2011), p. 28.</ref> the year 1984 began the present cycle (a 甲子—''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the [[new year]], when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the [[Chinese new year|lunar new year]] of the traditional [[Chinese calendar]]. For example, the yi-chou 己丑 year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (立春), which occurs near February 4.) |

year of the reign of [[Qin Shi Huang]] (秦始皇), 246 BC, is applied to the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term (51 of 60, 甲寅—''jiǎ - yín'') corresponding to that year.<ref>Kalinowski (1998), pp. 135–148, and fig. 3; Smith (2011), p. 29.</ref> Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the [[Western Han Dynasty]] (202 BC - 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since:<ref>Smith (2011), p. 28.</ref> the year 1984 began the present cycle (a 甲子—''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the [[new year]], when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the [[Chinese new year|lunar new year]] of the traditional [[Chinese calendar]]. For example, the yi-chou 己丑 year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (立春), which occurs near February 4.) |

||

In Japan, according to ''[[Nihon shoki]]'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the [[Empress Suiko|Suiko]] era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the [[Chinese calendar]], was the first year of the cycle.<ref>National Diet Library, [http://www.ndl.go.jp/koyomi/e/history/02_index1.html "Calendar History; the Source"]; retrieved 2013-1-1.</ref> |

In Japan, according to ''[[Nihon shoki]]'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the [[Empress Suiko|Suiko]] era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the [[Chinese calendar]], was the first year of the cycle.<ref>National Diet Library, [http://www.ndl.go.jp/koyomi/e/history/02_index1.html "Calendar History; the Source"] {{wayback|url=http://www.ndl.go.jp/koyomi/e/history/02_index1.html |date=20130106054946 }}; retrieved 2013-1-1.</ref> |

||

The Japanese tradition of celebrating {{nihongo|the 60th birthday|還暦|kanreki}} (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.<ref>Encyclopedia of Shinto, [http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=1040 "''Kanreki''"]; retrieved 2013-1-1.</ref> |

The Japanese tradition of celebrating {{nihongo|the 60th birthday|還暦|kanreki}} (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.<ref>Encyclopedia of Shinto, [http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=1040 "''Kanreki''"]; retrieved 2013-1-1.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:03, 22 November 2016

| Sexagenary cycle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 六十干支 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Stems-and-Branches | |||||||

| Chinese | 干支 | ||||||

| |||||||

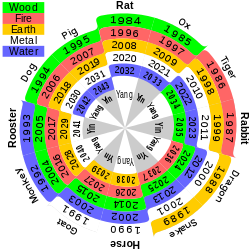

The Chinese sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches, is a cycle of sixty terms used for reckoning time.[1] It appears as a means of recording days in the first Chinese written texts, the Shang oracle bones of the late second millennium BC. Its use to record years began around the middle of the 3rd century BC.[2] The cycle and its variations have been an important part of the traditional calendrical systems in Chinese-influenced Asian states, particularly those of Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

This traditional method of numbering days and years no longer has any significant role in modern Chinese time keeping or the official calendar. However, the sexagenary cycle is still used in names of many historical events, like Chinese Xinhai Revolution and Japanese Boshin War. It also continues to have a role in contemporary Chinese astrology and fortune telling.

Overview

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter's duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term jiǎzǐ (甲子) combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term yǐchǒu (乙丑) combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with guǐhài (癸亥), after which it begins again at jiǎzǐ. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as jiǎchǒu (甲丑)—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.[3]

History

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1250 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the Spring and Autumn Annals, a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with reign years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.[4]

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest document showing this usage is a diagram among the silk manuscripts from Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. An annotation marking the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇), 246 BC, is applied to the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term (51 of 60, 甲寅—jiǎ - yín) corresponding to that year.[5] Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC - 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since:[6] the year 1984 began the present cycle (a 甲子—jiǎ-zǐ year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the yi-chou 己丑 year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (立春), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to Nihon shoki, the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.[7]

The Japanese tradition of celebrating the 60th birthday (還暦, kanreki) (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.[8]

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (丁卯—dīng-mǎo, year 4 on the Chinese cycle).[9]

Ten Heavenly Stems

| No. | Heavenly Stem |

Chinese name |

Japanese name |

Korean name |

Vietnamese name |

Yin Yang | Wu Xing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (Pinyin) |

Cantonese (Lau) |

Onyomi | Kunyomi with corresponding kanji |

Romanized | Hangul | |||||

| 1 | 甲 | jiǎ | gaap3 | kō (こう) | kinoe (木の兄) | gap | 갑 | giáp | yang | wood |

| 2 | 乙 | yǐ | yuet3 | otsu (おつ) | kinoto (木の弟) | eul | 을 | ất | yin | |

| 3 | 丙 | bǐng | bing2 | hei (へい) | hinoe (火の兄) | byeong | 병 | bính | yang | fire |

| 4 | 丁 | dīng | ding1 | tei (てい) | hinoto (火の弟) | jeong | 정 | đinh | yin | |

| 5 | 戊 | wù | mo6 | bo (ぼ) | tsuchinoe (土の兄) | mu | 무 | mậu | yang | earth |

| 6 | 己 | jǐ | gei2 | ki (き) | tsuchinoto (土の弟) | gi | 기 | kỷ | yin | |

| 7 | 庚 | gēng | gang1 | kō (こう) | kanoe (金の兄) | gyeong | 경 | canh | yang | metal |

| 8 | 辛 | xīn | san1 | shin (しん) | kanoto (金の弟) | shin | 신 | tân | yin | |

| 9 | 壬 | rén | yam4 | jin (じん) | mizunoe (水の兄) | im | 임 | nhâm | yang | water |

| 10 | 癸 | guǐ | gwai3 | ki (き) | mizunoto (水の弟) | gye | 계 | quý | yin | |

Twelve Earthly Branches

| No. | Earthly Branch |

Chinese name |

Japanese name |

Korean name |

Vietnamese name |

Vietnamese zodiac |

Chinese zodiac |

Corresponding hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (pinyin) |

Cantonese (Lau) |

Onyomi | Kunyomi | Romanized | Hangul | ||||||

| 1 | 子 | zǐ | ji2 | shi | ne | ja | 자 | tý | Rat (chuột) | Rat (鼠) | 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. |

| 2 | 丑 | chǒu | chau2 | chū | ushi | chuk | 축 | sửu | Water buffalo (trâu) | Ox (牛) | 1 to 3 a.m. |

| 3 | 寅 | yín | yan4 | in | tora | in | 인 | dần | Tiger (hổ/cọp) | Tiger (虎) | 3 to 5 a.m. |

| 4 | 卯 | mǎo | maau5 | bō | u | myo | 묘 | mão | Cat (mèo) | Rabbit (兔) | 5 to 7 a.m. |

| 5 | 辰 | chén | san4 | shin | tatsu | jin | 진 | thìn | Dragon (rồng) | Dragon (龍) | 7 to 9 a.m. |

| 6 | 巳 | sì | ji6 | shi | mi | sa | 사 | tỵ | Snake (rắn) | Snake (蛇) | 9 to 11 a.m. |

| 7 | 午 | wǔ | ng5 | go | uma | o | 오 | ngọ | Horse (ngựa) | Horse (馬) | 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. |

| 8 | 未 | wèi | mei6 | mi or bi | hitsuji | mi | 미 | mùi | Goat (dê) | Goat (羊) | 1 to 3 p.m. |

| 9 | 申 | shēn | san1 | shin | saru | shin | 신 | thân | Monkey (khỉ) | Monkey (猴) | 3 to 5 p.m. |

| 10 | 酉 | yǒu | jau5 | yū | tori | yu | 유 | dậu | Rooster (gà) | Rooster (雞) | 5 to 7 p.m. |

| 11 | 戌 | xū | sut1 | jutsu | inu | sul | 술 | tuất | Dog (chó) | Dog (狗) | 7 to 9 p.m. |

| 12 | 亥 | hài | hoi6 | gai | i | hae | 해 | hợi | Pig (lợn/heo) | Pig (豬) | 9 to 11 p.m. |

*The names of several animals can be translated into English in several different ways. The Vietnamese Earthly Branches use cat instead of Rabbit.

Sexagenary years

| No. | Stem-Branch | Chinese name | Korean name | Japanese name | Vietnamese name | Associations | AD | BC | Current Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 甲子 | jiǎ-zǐ | gapja 갑자 | kōshi(kasshi)/kinoe-ne | Giáp Tý | Yang Wood Rat | 4 | 57 | 1984 |

| 2 | 乙丑 | yǐ-chǒu | eulchuk 을축 | itchū/kinoto-ushi | Ất Sửu | Yin Wood Ox | 5 | 56 | 1985 |

| 3 | 丙寅 | bǐng-yín | byeongin 병인 | heiin/hinoe-tora | Bính Dần | Yang Fire Tiger | 6 | 55 | 1986 |

| 4 | 丁卯 | dīng-mǎo | jeongmyo 정묘 | teibō/hinoto-u | Đinh Mão | Yin Fire Rabbit | 7 | 54 | 1987 |

| 5 | 戊辰 | wù-chén | mujin 무진 | boshin/tsuchinoe-tatsu | Mậu Thìn | Yang Earth Dragon | 8 | 53 | 1988 |

| 6 | 己巳 | jǐ-sì | gisa 기사 | kishi/tsuchinoto-mi | Kỷ Tỵ | Yin Earth Snake | 9 | 52 | 1989 |

| 7 | 庚午 | gēng-wǔ | gyeongo 경오 | kōgo/kanoe-uma | Canh Ngọ | Yang Metal Horse | 10 | 51 | 1990 |

| 8 | 辛未 | xīn-wèi | sinmi 신미 | shinbi/kanoto-hitsuji | Tân Mùi | Yin Metal Goat | 11 | 50 | 1991 |

| 9 | 壬申 | rén-shēn | imsin 임신 | jinshin/mizunoe-saru | Nhâm Thân | Yang Water Monkey | 12 | 49 | 1992 |

| 10 | 癸酉 | guǐ-yǒu | gyeyu 계유 | kiyū/mizunoto-tori | Quý Dậu | Yin Water Rooster | 13 | 48 | 1993 |

| 11 | 甲戌 | jiǎ-xū | gapsul 갑술 | kōjutsu/kinoe-inu | Giáp Tuất | Yang Wood Dog | 14 | 47 | 1994 |

| 12 | 乙亥 | yǐ-hài | eulhae 을해 | itsugai/kinoto-i | Ât Hợi | Yin Wood Pig | 15 | 46 | 1995 |

| 13 | 丙子 | bǐng-zǐ | byeongja 병자 | heishi/hinoe-ne | Bính Tý | Yang Fire Rat | 16 | 45 | 1996 |

| 14 | 丁丑 | dīng-chǒu | jeongchuk 정축 | teichū/hinoto-ushi | Đinh Sửu | Yin Fire Ox | 17 | 44 | 1997 |

| 15 | 戊寅 | wù-yín | muin 무인 | boin/tsuchinoe-tora | Mậu Dần | Yang Earth Tiger | 18 | 43 | 1998 |

| 16 | 己卯 | jǐ-mǎo | gimyo 기묘 | kibō/tsuchinoto-u | Kỷ Mão | Yin Earth Rabbit | 19 | 42 | 1999 |

| 17 | 庚辰 | gēng-chén | gyeongjin 경진 | kōshin/kanoe-tatsu | Canh Thìn | Yang Metal Dragon | 20 | 41 | 2000 |

| 18 | 辛巳 | xīn-sì | sinsa 신사 | shinshi/kanoto-mi | Tân Tỵ | Yin Metal Snake | 21 | 40 | 2001 |

| 19 | 壬午 | rén-wǔ | imo 임오 | jingo/mizunoe-uma | Nhâm Ngọ | Yang Water Horse | 22 | 39 | 2002 |

| 20 | 癸未 | guǐ-wèi | gyemi 계미 | kibi/mizunoto-hitsuji | Quý Mùi | Yin Water Goat | 23 | 38 | 2003 |

| 21 | 甲申 | jiǎ-shēn | gapsin 갑신 | kōshin/kinoe-saru | Giáp Thân | Yang Wood Monkey | 24 | 37 | 2004 |

| 22 | 乙酉 | yǐ-yǒu | euryu 을유 | itsuyū/kinoto-tori | Ất Dậu | Yin Wood Rooster | 25 | 36 | 2005 |

| 23 | 丙戌 | bǐng-xū | byeongsul 병술 | heijutsu/hinoe-inu | Bính Tuất | Yang Fire Dog | 26 | 35 | 2006 |

| 24 | 丁亥 | dīng-hài | jeonghae 정해 | teigai/hinoto-i | Đinh Hợi | Yin Fire Pig | 27 | 34 | 2007 |

| 25 | 戊子 | wù-zǐ | muja 무자 | boshi/tsuchinoe-ne | Mậu Tý | Yang Earth Rat | 28 | 33 | 2008 |

| 26 | 己丑 | jǐ-chǒu | gichuk 기축 | kichū/tsuchinoto-ushi | Kỷ Sửu | Yin Earth Ox | 29 | 32 | 2009 |

| 27 | 庚寅 | gēng-yín | gyeongin 경인 | kōin/kanoe-tora | Canh Dần | Yang Metal Tiger | 30 | 31 | 2010 |

| 28 | 辛卯 | xīn-mǎo | sinmyo 신묘 | shinbō/kanoto-u | Tân Mão | Yin Metal Rabbit | 31 | 30 | 2011 |

| 29 | 壬辰 | rén-chén | imjin 임진 | jinshin/mizunoe-tatsu | Nhâm Thìn | Yang Water Dragon | 32 | 29 | 2012 |

| 30 | 癸巳 | guǐ-sì | gyesa 계사 | kishi/mizunoto-mi | Quý Tỵ | Yin Water Snake | 33 | 28 | 2013 |

| 31 | 甲午 | jiǎ-wǔ | gabo 갑오 | kōgo/kinoe-uma | Giáp Ngọ | Yang Wood Horse | 34 | 27 | 2014 |

| 32 | 乙未 | yǐ-wèi | eulmi 을미 | itsubi/kinoto-hitsuji | Ất Mùi | Yin Wood Goat | 35 | 26 | 2015 |

| 33 | 丙申 | bǐng-shēn | byeongsin 병신 | heishin/hinoe-saru | Bính Thân | Yang Fire Monkey | 36 | 25 | 2016 |

| 34 | 丁酉 | dīng-yǒu | jeongyu 정유 | teiyū/hinoto-tori | Đinh Dậu | Yin Fire Rooster | 37 | 24 | 2017 |

| 35 | 戊戌 | wù-xū | musul 무술 | bojutsu/tsuchinoe-inu | Mậu Tuất | Yang Earth Dog | 38 | 23 | 2018 |

| 36 | 己亥 | jǐ-hài | gihae 기해 | kigai/tsuchinoto-i | Kỷ Hợi | Yin Earth Pig | 39 | 22 | 2019 |

| 37 | 庚子 | gēng-zǐ | gyeongja 경자 | kōshi/kanoe-ne | Canh Tý | Yang Metal Rat | 40 | 21 | 2020 |

| 38 | 辛丑 | xīn-chǒu | sinchuk 신축 | shinchū/kanoto-ushi | Tân Sửu | Yin Metal Ox | 41 | 20 | 2021 |

| 39 | 壬寅 | rén-yín | imin 임인 | jin'in/mizunoe-tora | Nhâm Dần | Yang Water Tiger | 42 | 19 | 2022 |

| 40 | 癸卯 | guǐ-mǎo | gyemyo 계묘 | kibō/mizunoto-u | Quý Mão | Yin Water Rabbit | 43 | 18 | 2023 |

| 41 | 甲辰 | jiǎ-chén | gapjin 갑진 | kōshin/kinoe-tatsu | Giáp Thìn | Yang Wood Dragon | 44 | 17 | 2024 |

| 42 | 乙巳 | yǐ-sì | eulsa 을사 | itsushi/kinoto-mi | Ất Tỵ | Yin Wood Snake | 45 | 16 | 2025 |

| 43 | 丙午 | bǐng-wǔ | byeongo 병오 | heigo/hinoe-uma | Bính Ngọ | Yang Fire Horse | 46 | 15 | 2026 |

| 44 | 丁未 | dīng-wèi | jeongmi 정미 | teibi/hinoto-hitsuji | Đinh Mùi | Yin Fire Goat | 47 | 14 | 2027 |

| 45 | 戊申 | wù-shēn | musin 무신 | boshin/tsuchinoe-saru | Mậu Thân | Yang Earth Monkey | 48 | 13 | 2028 |

| 46 | 己酉 | jǐ-yǒu | giyu 기유 | kiyū/tsuchinoto-tori | Kỷ Dậu | Yin Earth Rooster | 49 | 12 | 2029 |

| 47 | 庚戌 | gēng-xū | gyeongsul 경술 | kōjutsu/kanoe-inu | Canh Tuất | Yang Metal Dog | 50 | 11 | 2030 |

| 48 | 辛亥 | xīn-hài | sinhae 신해 | shingai/kanoto-i | Tân Hợi | Yin Metal Pig | 51 | 10 | 2031 |

| 49 | 壬子 | rén-zǐ | imja 임자 | jinshi/mizunoe-ne | Nhâm Tý | Yang Water Rat | 52 | 9 | 2032 |

| 50 | 癸丑 | guǐ-chǒu | gyechuk 계축 | kichū/mizunoto-ushi | Quý Sửu | Yin Water Ox | 53 | 8 | 2033 |

| 51 | 甲寅 | jiǎ-yín | gabin 갑인 | kōin/kinoe-tora | Giáp Dần | Yang Wood Tiger | 54 | 7 | 2034 |

| 52 | 乙卯 | yǐ-mǎo | eulmyo 을묘 | itsubō/kinoto-u | Ất Mão | Yin Wood Rabbit | 55 | 6 | 2035 |

| 53 | 丙辰 | bǐng-chén | byeongjin 병진 | heishin/hinoe-tatsu | Bính Thìn | Yang Fire Dragon | 56 | 5 | 2036 |

| 54 | 丁巳 | dīng-sì | jeongsa 정사 | teishi/hinoto-mi | Đinh Tỵ | Yin Fire Snake | 57 | 4 | 2037 |

| 55 | 戊午 | wù-wǔ | muo 무오 | bogo/tsuchinoe-uma | Mậu Ngọ | Yang Earth Horse | 58 | 3 | 2038 |

| 56 | 己未 | jǐ-wèi | gimi 기미 | kibi/tsuchinoto-hitsuji | Kỷ Mùi | Yin Earth Goat | 59 | 2 | 2039 |

| 57 | 庚申 | gēng-shēn | gyeongsin 경신 | kōshin/kanoe-saru | Canh Thân | Yang Metal Monkey | 60 | 1 | 2040 |

| 58 | 辛酉 | xīn-yǒu | sinyu 신유 | shin'yū/kanoto-tori | Tân Dậu | Yin Metal Rooster | 1 | 60 | 2041 |

| 59 | 壬戌 | rén-xū | imsul 임술 | jinjutsu/mizunoe-inu | Nhâm Tuất | Yang Water Dog | 2 | 59 | 2042 |

| 60 | 癸亥 | guǐ-hài | gyehae 계해 | kigai/mizunoto-i | Quý Hợi | Yin Water Pig | 3 | 58 | 2043 |

Conversion between cyclic years and Western years

As mentioned above, the cycle first started to be used for indicating years during the Han Dynasty, but of course it can be used to indicate earlier years retroactively. Since it repeats, by itself it cannot specify a year without some other information, but it is frequently used with the Chinese era name (年号; "niánhào") to specify a year.[10] Of course, the year starts with the new year of whoever is using the calendar. In China, the cyclic year normally changes on the Chinese Lunar New Year. In Japan until recently it was the Japanese lunar new year, which was sometimes different from the Chinese; now it is January 1. So when calculating the cyclic year of a date in the Gregorian year, you have to consider what your "new year" is. Hence, the following calculation deals with the Chinese dates after the Lunar New Year in that Gregorian year; to find the corresponding sexagenary year in the dates before the Lunar New Year would require the Gregorian year to be decreased by 1.

As for example, the year 2697 BC (or -2696, using the astronomical year count), traditionally the first year of the reign of the legendary Yellow Emperor, was the first year (甲子; jiǎ-zǐ) of a cycle. 2700 years later in 4 AD, the duration equivalent to 45 60-year cycles, was also the starting year of a 60-year cycle. Similarly 1980 years later, 1984 was the start of a new cycle.

Thus, to find out the Gregorian year's equivalent in the sexagenary cycle use the appropriate method below.

- For any year number greater than 4 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by subtracting 3 from the Gregorian year, dividing by 60 and taking the remainder. See example below.

- For any year before 1 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by adding 2 to the Gregorian year number (in BC), dividing it by 60, and subtracting the remainder from 60. See example below.

- 1 AD, 2 AD and 3 AD correspond respectively to the 58th, 59th and 60th years of the sexagenary cycle.

The result will produce a number between 0 and 59, corresponding to the year order in the cycle; if the remainder is 0, it corresponds to the 60th year of a cycle. Thus, using the first method, the equivalent sexagenary year for 2012 AD is the 29th year (壬辰; rén-chén), as (2012-3) mod 60 = 29 (i.e., the remainder of (2012-3 divided by 60 is 29). Using the second, the equivalent sexagenary year for 221 BC is the 17th year (庚辰; gēng-chén), as 60- [(221+2) mod 60] = 17 (i.e., 60 minus the remainder of (221+2) divided by 60 is 17).

Examples

Step-by-step example to determine the sign for 1967:

- 1967 - 3 = 1964 ("subtracting 3 from the Gregorian year")

- 1964 ÷ 60 = 32 ("divide by 60 and discard any fraction")

- 1964 - (60 × 32) = 44 ("taking the remainder")

- Open the table 'Sexagenary Cycle' (the preceding section), look for 44 in the first column (No) and obtain Fire Goat (丁未; dīng-wèi).

Step-by-step example to determine the cyclic year of first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (246 BC):

- 246 + 2 = 248 ("adding 2 to the Gregorian year number (in BC)")

- 248 ÷ 60 = 4 ("divide by 60 and discard any fraction")

- 248 - (60 × 4) = 8 ("taking the remainder")

- 60 - 8 = 52 ("subtract the remainder from 60")

- Open the table 'Sexagenary Cycle' (the preceding section), look for 52 in the first column (No) and obtain Wood Rabbit (乙卯; yǐ-mǎo).

A shorter equivalent method

Start from the AD year, take directly the remainder mod 60, and look into column AD:

- 1967 = 60 × 32 + 47. Remainder is therefore 47 and the AD column of the same table gives 'Fire Goat'

For a BC year: discard the minus sign, take the remainder of the year mod 60 and look into column BC:

- 246 = 60 × 4 + 6. Remainder is therefore 6 and the BC column of the same table gives 'Wood Rabbit'.

When doing these conversions, year 246 BC cannot be treated as -246 AD due to the lack of a year 0 in the Gregorian AD/BC system.

The following tables show recent years (in the Gregorian calendar) and their corresponding years in the cycles:

1804–1923

| No. | 1804–1863 | Heavenly stem | Earthly branch | 1864–1923 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | (Elements) | (Animals) | Year | |

| 1 | Feb 11 1804 – Jan 30 1805 | 甲 Yang Wood | 子 Rat | Feb 8 1864 – Jan 26 1865 |

| 2 | Jan 31 1805 – Feb 17 1806 | 乙 Yin Wood | 丑 Ox | Jan 27 1865 – ~~ 1866 |

| 3 | Feb 18 1806 – Feb 6 1807 | 丙 Yang Fire | 寅 Tiger | ~~ 1866 – ~~ 1867 |

| 4 | Feb 7 1807 – Jan 27 1808 | 丁 Yin Fire | 卯 Rabbit | ~~ 1867 – ~~ 1868 |

| 5 | Jan 28 1808 – Feb 13 1809 | 戊 Yang Earth | 辰 Dragon | ~~ 1868 – ~~ 1869 |

| 6 | Feb 14 1809 – Feb 3 1810 | 己 Yin Earth | 巳 Snake | ~~ 1869 – Jan 30 1870 |

| 7 | Feb 4 1810 – Jan 24 1811 | 庚 Yang Metal | 午 Horse | Jan 31 1870 – Feb 18 1871 |

| 8 | Jan 25 1811 – Feb 12 1812 | 辛 Yin Metal | 未 Goat | Feb 19 1871 – ~~ 1872 |

| 9 | Feb 13 1812 – Jan 31 1813 | 壬 Yang Water | 申 Monkey | ~~ 1872 – ~~ 1873 |

| 10 | Feb 1 1813 – Feb 19 1814 | 癸 Yin Water | 酉 Rooster | ~~ 1873 – ~~ 1874 |

| 11 | Feb 201814 – Feb 8 1815 | 甲 Yang Wood | 戌 Dog | ~~ 1874 – ~~ 1875 |

| 12 | Feb 9 1815 – Jan 28 1816 | 乙 Yin Wood | 亥 Pig | ~~ 1875 – ~~ 1876 |

| 13 | Jan 29 1816 – Jan 16 1817 | 丙 Yang Fire | 子 Rat | ~~ 1876 – ~~ 1877 |

| 14 | Jan 17 1817 – Feb 4 1818 | 丁 Yin Fire | 丑 Ox | ~~ 1877 – ~~ 1878 |

| 15 | Feb 5 1818 – Jan 25 1819 | 戊 Yang Earth | 寅 Tiger | ~~ 1878 – ~~ 1879 |

| 16 | ~~ 1819 – ~~ 1820 | 己 Yin Earth | 卯 Rabbit | ~~ 1879 – ~~ 1880 |

| 17 | ~~ 1820 – ~~ 1821 | 庚 Yang Metal | 辰 Dragon | ~~ 1880 – ~~ 1881 |

| 18 | ~~ 1821 – ~~ 1822 | 辛 Yin Metal | 巳 Snake | ~~ 1881 – ~~ 1882 |

| 19 | ~~ 1822 – ~~ 1823 | 壬 Yang Water | 午 Horse | ~~ 1882 – ~~ 1883 |

| 20 | ~~ 1823 – ~~ 1824 | 癸 Yin Water | 未 Goat | ~~ 1883 – ~~ 1884 |

| 21 | ~~ 1824 – ~~ 1825 | 甲 Yang Wood | 申 Monkey | ~~ 1884 – ~~ 1885 |

| 22 | ~~ 1825 – ~~ 1826 | 乙 Yin Wood | 酉 Rooster | ~~ 1885 – ~~ 1886 |

| 23 | ~~ 1826 – ~~ 1827 | 丙 Yang Fire | 戌 Dog | ~~ 1886 – ~~ 1887 |

| 24 | ~~ 1827 – ~~ 1828 | 丁 Yin Fire | 亥 Pig | ~~ 1887 – ~~ 1888 |

| 25 | ~~ 1828 – ~~ 1829 | 戊 Yang Earth | 子 Rat | ~~ 1888 – Jan 30 1889 |

| 26 | ~~ 1829 – ~~ 1830 | 己 Yin Earth | 丑 Ox | Jan 31 1889 – Jan 20 1890 |

| 27 | ~~ 1830 – ~~ 1831 | 庚 Yang Metal | 寅 Tiger | Jan 21 1890 – Feb 08 1891 |

| 28 | ~~ 1831 – ~~ 1832 | 辛 Yin Metal | 卯 Rabbit | Feb 09 1891 – ~~ 1892 |

| 29 | ~~ 1832 – ~~ 1833 | 壬 Yang Water | 辰 Dragon | ~~ 1892 – ~~ 1893 |

| 30 | ~~ 1833 – ~~ 1834 | 癸 Yin Water | 巳 Snake | ~~ 1893 – ~~ 1894 |

| 31 | ~~ 1834 – ~~ 1835 | 甲 Yang Wood | 午 Horse | ~~ 1894 – ~~ 1895 |

| 32 | ~~ 1835 – ~~ 1836 | 乙 Yin Wood | 未 Goat | ~~ 1895 – Feb 12 1896 |

| 33 | ~~ 1836 – ~~ 1837 | 丙 Yang Fire | 申 Monkey | Feb 13 1896 – Feb 01 1897 |

| 34 | ~~ 1837 – ~~ 1838 | 丁 Yin Fire | 酉 Rooster | Feb 02 1897 – Jan 21 1898 |

| 35 | ~~ 1838 – ~~ 1839 | 戊 Yang Earth | 戌 Dog | Jan 22 1898 – Feb 09 1899 |

| 36 | ~~ 1839 – ~~ 1840 | 己 Yin Earth | 亥 Pig | Feb 10 1899 – Jan 30 1900 |

| 37 | ~~ 1840 – ~~ 1841 | 庚 Yang Metal | 子 Rat | Jan 31 1900 – Feb 18 1901 |

| 38 | ~~ 1841 – ~~ 1842 | 辛 Yin Metal | 丑 Ox | Feb 19 1901 – Feb 07 1902 |

| 39 | ~~ 1842 – ~~ 1843 | 壬 Yang Water | 寅 Tiger | Feb 08 1902 – Jan 28 1903 |

| 40 | ~~ 1843 – ~~ 1844 | 癸 Yin Water | 卯 Rabbit | Jan 29 1903 – Feb 15 1904 |

| 41 | ~~ 1844 – ~~ 1845 | 甲 Yang Wood | 辰 Dragon | Feb 16 1904 – Feb 03 1905 |

| 42 | ~~ 1845 – ~~ 1846 | 乙 Yin Wood | 巳 Snake | Feb 04 1905 – Jan 24 1906 |

| 43 | ~~ 1846 – ~~ 1847 | 丙 Yang Fire | 午 Horse | Jan 25 1906 – Feb 12 1907 |

| 44 | ~~ 1847 – ~~ 1848 | 丁 Yin Fire | 未 Goat | Feb 13 1907 – Feb 01 1908 |

| 45 | ~~ 1848 – ~~ 1849 | 戊 Yang Earth | 申 Monkey | Feb 02 1908 – Jan 21 1909 |

| 46 | ~~ 1849 – ~~ 1850 | 己 Yin Earth | 酉 Rooster | Jan 22 1909 – Feb 09 1910 |

| 47 | ~~ 1850 – ~~ 1851 | 庚 Yang Metal | 戌 Dog | Feb 10 1910 – Jan 29 1911 |

| 48 | ~~ 1851 – ~~ 1852 | 辛 Yin Metal | 亥 Pig | Jan 30 1911 – Feb 17 1912 |

| 49 | ~~ 1852 – ~~ 1853 | 壬 Yang Water | 子 Rat | Feb 18 1912 – Feb 05 1913 |

| 50 | ~~ 1853 – ~~ 1854 | 癸 Yin Water | 丑 Ox | Feb 06 1913 – Jan 25 1914 |

| 51 | ~~ 1854 – ~~ 1855 | 甲 Yang Wood | 寅 Tiger | Jan 26 1914 – Feb 13 1915 |

| 52 | ~~ 1855 – ~~ 1856 | 乙 Yin Wood | 卯 Rabbit | Feb 14 1915 – Feb 02 1916 |

| 53 | ~~ 1856 – ~~ 1857 | 丙 Yang Fire | 辰 Dragon | Feb 03 1916 – Jan 22 1917 |

| 54 | ~~ 1857 – ~~ 1858 | 丁 Yin Fire | 巳 Snake | Jan 23 1917 – Feb 10 1918 |

| 55 | ~~ 1858 – ~~ 1859 | 戊 Yang Earth | 午 Horse | Feb 11 1918 – Jan 31 1919 |

| 56 | ~~ 1859 – ~~ 1860 | 己 Yin Earth | 未 Goat | Feb 01 1919 – Feb 19 1920 |

| 57 | ~~ 1860 – ~~ 1861 | 庚 Yang Metal | 申 Monkey | Feb 20 1920 – Feb 07 1921 |

| 58 | ~~ 1861 – ~~ 1862 | 辛 Yin Metal | 酉 Rooster | Feb 08 1921 – Jan 27 1922 |

| 59 | ~~ 1862 – ~~ 1863 | 壬 Yang Water | 戌 Dog | Jan 28 1922 – Feb 15 1923 |

| 60 | ~~ 1863 – Feb 7 1864 | 癸 Yin Water | 亥 Pig | Feb 16 1923 – Feb 04 1924 |

1924–2043

| No. | 1924–1983 | Heavenly stem | Earthly branch | 1984–2043 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | (Elements) | (Animals) | Year | |

| 1 | Feb 05 1924 – Jan 23 1925 | 甲 Yang Wood | 子 Rat | Feb 02 1984 – Feb 19 1985 |

| 2 | Jan 24 1925 – Feb 12 1926 | 乙 Yin Wood | 丑 Ox | Feb 20 1985 – Feb 08 1986 |

| 3 | Feb 13 1926 – Feb 01 1927 | 丙 Yang Fire | 寅 Tiger | Feb 09 1986 – Jan 28 1987 |

| 4 | Feb 02 1927 – Jan 21 1928 | 丁 Yin Fire | 卯 Rabbit | Jan 29 1987 – Feb 16 1988 |

| 5 | Jan 22 1928 – Feb 08 1929 | 戊 Yang Earth | 辰 Dragon | Feb 17 1988 – Feb 05 1989 |

| 6 | Feb 09 1929 – Jan 28 1930 | 己 Yin Earth | 巳 Snake | Feb 06 1989 – Jan 26 1990 |

| 7 | Jan 29 1930 – Feb 16 1931 | 庚 Yang Metal | 午 Horse | Jan 27 1990 – Feb 13 1991 |

| 8 | Feb 17 1931 – Feb 05 1932 | 辛 Yin Metal | 未 Goat | Feb 14 1991 – Feb 03 1992 |

| 9 | Feb 06 1932 – Jan 24 1933 | 壬 Yang Water | 申 Monkey | Feb 04 1992 – Jan 22 1993 |

| 10 | Jan 25 1933 – Feb 13 1934 | 癸 Yin Water | 酉 Rooster | Jan 23 1993 – Feb 09 1994 |

| 11 | Feb 14 1934 – Feb 02 1935 | 甲 Yang Wood | 戌 Dog | Feb 10 1994 – Jan 30 1995 |

| 12 | Feb 03 1935 – Jan 23 1936 | 乙 Yin Wood | 亥 Pig | Jan 31 1995 – Feb 18 1996 |

| 13 | Jan 24 1936 – Feb 10 1937 | 丙 Yang Fire | 子 Rat | Feb 19 1996 – Feb 06 1997 |

| 14 | Feb 11 1937 – Jan 30 1938 | 丁 Yin Fire | 丑 Ox | Feb 07 1997 – Jan 27 1998 |

| 15 | Jan 31 1938 – Feb 18 1939 | 戊 Yang Earth | 寅 Tiger | Jan 28 1998 – Feb 15 1999 |

| 16 | Feb 19 1939 – Feb 07 1940 | 己 Yin Earth | 卯 Rabbit | Feb 16 1999 – Feb 04 2000 |

| 17 | Feb 08 1940 – Jan 26 1941 | 庚 Yang Metal | 辰 Dragon | Feb 05 2000 – Jan 23 2001 |

| 18 | Jan 27 1941 – Feb 14 1942 | 辛 Yin Metal | 巳 Snake | Jan 24 2001 – Feb 11 2002 |

| 19 | Feb 15 1942 – Feb 04 1943 | 壬 Yang Water | 午 Horse | Feb 12 2002 – Jan 31 2003 |

| 20 | Feb 05 1943 – Jan 24 1944 | 癸 Yin Water | 未 Goat | Feb 01 2003 – Jan 21 2004 |

| 21 | Jan 25 1944 – Feb 12 1945 | 甲 Yang Wood | 申 Monkey | Jan 22 2004 – Feb 08 2005 |

| 22 | Feb 13 1945 – Feb 01 1946 | 乙 Yin Wood | 酉 Rooster | Feb 09 2005 – Jan 28 2006 |

| 23 | Feb 02 1946 – Jan 21 1947 | 丙 Yang Fire | 戌 Dog | Jan 29 2006 – Feb 17 2007 |

| 24 | Jan 22 1947 – Feb 09 1948 | 丁 Yin Fire | 亥 Pig | Feb 18 2007 – Feb 03 2008 |

| 25 | Feb 10 1948 – Jan 28 1949 | 戊 Yang Earth | 子 Rat | Feb 07 2008 – Jan 25 2009 |

| 26 | Jan 29 1949 – Feb 16 1950 | 己 Yin Earth | 丑 Ox | Jan 26 2009 – Feb 13 2010 |

| 27 | Feb 17 1950 – Feb 05 1951 | 庚 Yang Metal | 寅 Tiger | Feb 14 2010 – Feb 02 2011 |

| 28 | Feb 06 1951 – Jan 26 1952 | 辛 Yin Metal | 卯 Rabbit | Feb 03 2011 – Jan 22 2012 |

| 29 | Jan 27 1952 – Feb 13 1953 | 壬 Yang Water | 辰 Dragon | Jan 23 2012 – Feb 09 2013 |

| 30 | Feb 14 1953 – Feb 02 1954 | 癸 Yin Water | 巳 Snake | Feb 10 2013 – Jan 30 2014 |

| 31 | Feb 03 1954 – Jan 23 1955 | 甲 Yang Wood | 午 Horse | Jan 31 2014 – Feb 18 2015 |

| 32 | Jan 24 1955 – Feb 11 1956 | 乙 Yin Wood | 未 Goat | Feb 19 2015 – Feb 07 2016 |

| 33 | Feb 12 1956 – Jan 30 1957 | 丙 Yang Fire | 申 Monkey | Feb 08 2016 – Jan 27 2017 |

| 34 | Jan 30 1957 – Feb 17 1958 | 丁 Yin Fire | 酉 Rooster | Jan 28 2017 – Feb 15 2018 |

| 35 | Feb 18 1958 – Feb 07 1959 | 戊 Yang Earth | 戌 Dog | Feb 16 2018 – Feb 04 2019 |

| 36 | Feb 08 1959 – Jan 27 1960 | 己 Yin Earth | 亥 Pig | Feb 05 2019 – Jan 24 2020 |

| 37 | Jan 28 1960 – Feb 14 1961 | 庚 Yang Metal | 子 Rat | Jan 25 2020 – Feb 11 2021 |

| 38 | Feb 15 1961 – Feb 04 1962 | 辛 Yin Metal | 丑 Ox | Feb 12 2021 – Jan 31 2022 |

| 39 | Feb 05 1962 – Jan 24 1963 | 壬 Yang Water | 寅 Tiger | Feb 01 2022 – Jan 21 2023 |

| 40 | Jan 25 1963 – Feb 12 1964 | 癸 Yin Water | 卯 Rabbit | Jan 22 2023 – Feb 09 2024 |

| 41 | Feb 13 1964 – Feb 01 1965 | 甲 Yang Wood | 辰 Dragon | Feb 10 2024 – Jan 28 2025 |

| 42 | Feb 02 1965 – Jan 20 1966 | 乙 Yin Wood | 巳 Snake | Jan 29 2025 – Feb 16 2026 |

| 43 | Jan 21 1966 – Feb 08 1967 | 丙 Yang Fire | 午 Horse | Feb 17 2026 – Feb 05 2027 |

| 44 | Feb 09 1967 – Jan 29 1968 | 丁 Yin Fire | 未 Goat | Feb 06 2027 – Jan 25 2028 |

| 45 | Jan 30 1968 – Feb 16 1969 | 戊 Yang Earth | 申 Monkey | Jan 26 2028 – Feb 12 2029 |

| 46 | Feb 17 1969 – Feb 05 1970 | 己 Yin Earth | 酉 Rooster | Feb 13 2029 – Feb 02 2030 |

| 47 | Feb 06 1970 – Jan 26 1971 | 庚 Yang Metal | 戌 Dog | Feb 03 2030 – Jan 22 2031 |

| 48 | Jan 27 1971 – Feb 14 1972 | 辛 Yin Metal | 亥 Pig | Jan 23 2031 – Feb 10 2032 |

| 49 | Feb 15 1972 – Feb 02 1973 | 壬 Yang Water | 子 Rat | Feb 11 2032 – Jan 30 2033 |

| 50 | Feb 03 1973 – Jan 24 1974 | 癸 Yin Water | 丑 Ox | Jan 31 2033 – Feb 18 2034 |

| 51 | Jan 23 1974 – Feb 10 1975 | 甲 Yang Wood | 寅 Tiger | Feb 19 2034 – Feb 07 2035 |

| 52 | Feb 11 1975 – Jan 30 1976 | 乙 Yin Wood | 卯 Rabbit | Feb 08 2035 – Jan 27 2036 |

| 53 | Jan 31 1976 – Feb 17 1977 | 丙 Yang Fire | 辰 Dragon | Jan 28 2036 – Feb 14 2037 |

| 54 | Feb 18 1977 – Feb 06 1978 | 丁 Yin Fire | 巳 Snake | Feb 15 2037 – Feb 03 2038 |

| 55 | Feb 07 1978 – Jan 27 1979 | 戊 Yang Earth | 午 Horse | Feb 04 2038 – Jan 23 2039 |

| 56 | Jan 28 1979 – Feb 15 1980 | 己 Yin Earth | 未 Goat | Jan 24 2039 – Feb 11 2040 |

| 57 | Feb 16 1980 – Feb 04 1981 | 庚 Yang Metal | 申 Monkey | Feb 12 2040 – Jan 31 2041 |

| 58 | Feb 05 1981 – Jan 24 1982 | 辛 Yin Metal | 酉 Rooster | Feb 01 2041 – Jan 21 2042 |

| 59 | Jan 25 1982 – Feb 12 1983 | 壬 Yang Water | 戌 Dog | Jan 22 2042 – Feb 09 2043 |

| 60 | Feb 13 1983 – Feb 01 1984 | 癸 Yin Water | 亥 Pig | Feb 10 2043 – Jan 29 2044 |

Months in Sexagenary Cycle

The branches are used marginally to indicate months. Despite there being twelve branches and twelve months in a year, the earliest use of branches to indicate a twelve-fold division of a year was in the 2nd century BC. They were coordinated with the orientations of the Great Dipper, (建子月—jiànzǐyuè, 建丑月—jiànchǒuyuè, etc.).[11] There are two systems of placing these months, the lunar one and the solar one.

One system follows the ordinary Chinese lunar calendar and connects the names of the months directly to the central solar term (中氣; zhōngqì). The jiànzǐyuè ((建)子月) is the month containing the winter solstice (i.e. the 冬至— Dōngzhì) zhōngqì. The jiànchǒuyuè ((建)丑月) is the month of the following zhōngqì, which is Dàhán (大寒), while the jiànyínyuè ((建)寅月) is that of the Yǔshuǐ (雨水) zhōngqì, etc. Intercalary months have the same branch as the preceding month.

In the other system (節月; jiéyuè) the "month" lasts for the period of two solar terms (two 氣策—qìcì). The zǐyuè (子月) is the period starting with Dàxuě (大雪), i.e. the solar term before the winter solstice. The chǒuyuè (丑月) starts with Xiǎohán (小寒), the term before Dàhán (大寒), while the yínyuè (寅月) starts with Lìchūn (立春), the term before Yǔshuǐ (雨水), etc. Thus in the solar system a month starts anywhere from about 15 days before to 15 days after its lunar counterpart.

The branch names are not usual month names; the main use of the branches for months is astrological. However, the names are sometimes used to indicate historically which (lunar) month was the first month of the year in ancient times. For example, since the Han Dynasty, the first month has been jiànyínyuè, but earlier the first month was jiànzǐyuè (during the Zhou Dynasty) or jiànchǒuyuè (traditionally during the Shang Dynasty) as well.[12]

For astrological purposes stems are also necessary, and the months are named using the sexegenary cycle following a five-year cycle starting in a jiǎ (甲; 1st) or jǐ (己; 6th) year. The first month of the jiǎ or jǐ year is a bǐng-yín (丙寅; 3rd) month, the next one is a dīng-mǎo (丁卯; 4th) month, etc., and the last month of the year is a dīng-chǒu (丁丑, 14th) month. The next year will start with a wù-yín (戊寅; 15th) month, etc. following the cycle. The 5th year will end with a yǐ-chǒu (乙丑; 2nd) month. The following month, the start of a jǐ or jiǎ year, will hence again be a bǐng-yín (3rd) month again. The beginning and end of the (solar) months in the table below are the approximate dates of current solar terms; they vary slightly from year to year depending on the leap days of the Gregorian calendar.

| Earthly Branches of the certain months | Solar term | Zhongqi (the Middle solar term) | Starts at | Ends at | Names in year of Jia or Ji(甲/己年) | Names in year of Yi or Geng (乙/庚年) | Names in year of Bing or Xin (丙/辛年) | Names in year of Ding or Ren (丁/壬年) | Names in year of Wu or Gui (戊/癸年) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month of Yin (寅月) | Lichun - Jingzhe | Yushui | February 4 | March 6 | Bingyin / 丙寅月 | Wuyin / 戊寅月 | Gengyin / 庚寅月 | Renyin / 壬寅月 | Jiayin / 甲寅月 |

|

Month of Mao (卯月) |

Jingzhe - Qingming | Chunfen | March 6 | April 5 | Dingmao / 丁卯月 | Jimao / 己卯月 | Xinmao / 辛卯月 | Guimao / 癸卯月 | Yimao / 乙卯月 |

| Month of Chen (辰月) | Qingming - Lixia | Guyu | April 5 | May 6 | Wuchen / 戊辰月 | Gengchen / 庚辰月 | Renchen / 壬辰月 | Jiachen / 甲辰月 | Bingchen / 丙辰月 |

| Month of Si (巳月) | Lixia - Mangzhong | Xiaoman | May 6 | June 6 | Jisi / 己巳月 | Xinsi / 辛巳月 | Guisi / 癸巳月 | Yisi / 乙巳月 | Dingsi / 丁巳月 |

| Month of Wu (午月) | Mangzhong - Xiaoshu | Xiazhi | June 6 | July 7 | Gengwu / 庚午月 | Renwu / 壬午月 | Jiawu / 甲午月 | Bingwu / 丙午月 | Wuwu / 戊午月 |

| Month of Wei (未月) | Xiaoshu - Liqiu | Dashu | July 7 | August 8 | Xinwei / 辛未月 | Guiwei / 癸未月 | Yiwei / 乙未月 | Dingwei / 丁未月 | Jiwei / 己未月 |

| Month of Shen (申月) | Liqiu - Bailu | Chushu | August 8 | September 8 | Renshen / 壬申月 | Jiashen / 甲申月 | Bingshen / 丙申月 | Wushen / 戊申月 | Gengshen / 庚申月 |

| Month of You (酉月) | Bailu - Hanlu | Qiufen | September 8 | October 8 | Guiyou / 癸酉月 | Yiyou / 乙酉月 | Dingyou / 丁酉月 | Jiyou / 己酉月 | Xinyou / 辛酉月 |

| Month of Xu (戌月) | Hanlu - Lidong | Shuangjiang | October 8 | November 7 | Jiaxu / 甲戌月 | Bingxu / 丙戌月 | Wuxu / 戊戌月 | Gengxu / 庚戌月 | Renxu / 壬戌月 |

| Month of Hai (亥月) | Lidong - Daxue | Xiaoxue | November 7 | December 7 | Yihai / 乙亥月 | Dinghai / 丁亥月 | Jihai / 己亥月 | Xinhai / 辛亥月 | Guihai / 癸亥月 |

| Month of Zi (子月) | Daxue - Xiaohan | Dongzhi | December 7 | January 6 | Bingzi / 丙子月 | Wuzi / 戊子月 | Gengzi / 庚子月 | Renzi / 壬子月 | Jiazi / 甲子月 |

| Month of Chou (丑月) | Xiaohan - Lichun | Dahan | January 6 | February 4 | Dingchou / 丁丑月 | Jichou / 己丑月 | Xinchou / 辛丑月 | Guichou / 癸丑月 | Yichou / 乙丑月 |

See also

- Chinese calendar

- Lunisolar calendar

- Tai Sui

- Samvatsara

- Xinhai Revolution, named after the "Yin Metal Pig" year 1911

- Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) - Korean name of the event, "Imjin War", named after the "Yang Water Dragon/Imjin" year 1592.

Notes

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Jikkan-jūnishi" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 420.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 1, 28.

- ^ For the Akan calendar, see Bartle (1978).

- ^ Smith (2011), p. 24,26-27.

- ^ Kalinowski (1998), pp. 135–148, and fig. 3; Smith (2011), p. 29.

- ^ Smith (2011), p. 28.

- ^ National Diet Library, "Calendar History; the Source" Archived 2013-01-06 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 2013-1-1.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Shinto, "Kanreki"; retrieved 2013-1-1.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya, Alaka. (1999). Atisa and Tibet: Life and Works of Dipamkara Srijnana in relation to the history and religion of Tibet, pp. 566-568.

- ^ The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar

- ^ Smith (2011), p. 28, p. 29 fn2, ; Entry "建す” in the standard dictionary 広辞苑, 東京:岩波.

- ^ Entry "三正” in the standard dictionary 広辞苑, 東京:岩波.

Bibliography

Bartle, P. F. W. (1978). "Forty days: the Akan calendar". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 48 (1): 80–84. doi:10.2307/1158712.

Kalinowski, Marc (2007). "Time, space and orientation: figurative representations of the sexagenary cycle in ancient and medieval China". In Francesca Bray (ed.). Graphics and text in the production of technical knowledge in China : the warp and the weft. Leiden: Brill. pp. 137–168. ISBN 978-90-04-16063-7.

Smith, Adam (2011). "The Chinese sexagenary cycle and the ritual origins of the calendar". In John Steele (ed.). Calendars and years II : astronomy and time in the ancient and medieval world (PDF). Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-1-84217-987-1.