Edwin Lutyens: Difference between revisions

m →New Delhi: clean up; http→https for The Guardian using AWB |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.7.1) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

[[File:Portland.stone.cenotaph.london.arp.jpg|thumb|left|[[The Cenotaph, Whitehall|The Cenotaph]], Whitehall, London]] |

[[File:Portland.stone.cenotaph.london.arp.jpg|thumb|left|[[The Cenotaph, Whitehall|The Cenotaph]], Whitehall, London]] |

||

Before the end of [[World War I]], he was appointed one of three principal architects for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now [[Commonwealth War Graves Commission]]) and was involved with the creation of [[World War I memorials|many monuments to commemorate the dead]]. Larger cemeteries have a [[Stone of Remembrance]], designed by him.<ref>[http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0009128 Canadian Encyclopedia Monuments, World Wars I and II]</ref> The best known of these monuments are the [[The Cenotaph, Whitehall|Cenotaph]] in [[Whitehall]], [[Westminster]], and the [[Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme|Memorial to the Missing of the Somme]], [[Thiepval]]. The Cenotaph was originally commissioned by [[David Lloyd George]] as a temporary structure to be the centrepiece of the Allied Victory Parade in 1919. Lloyd George proposed a [[catafalque]], a low empty platform, but it was Lutyens' idea for the taller monument. The design took less than six hours to complete. Many local war memorials such as the one at [[All Saints' Church, Northampton|All Saints', Northampton]], [[Montréal]], Toronto, [[Hamilton, Ontario|Hamilton (Ontario)]], [[Victoria, British Columbia|Victoria (British Columbia)]], and [[Vancouver]] are Lutyens designs, based on the Cenotaph. So is the war memorial in Hyde Park, Sydney. He also designed the [[National War Memorial, Islandbridge|War Memorial Gardens]] in Dublin, which were restored in the 1990s. Other works include the [[Tower Hill memorial]], and (similar to his later [[India Gate]] design) the [[Arch of Remembrance]] memorial in [[Victoria Park, Leicester]]. |

Before the end of [[World War I]], he was appointed one of three principal architects for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now [[Commonwealth War Graves Commission]]) and was involved with the creation of [[World War I memorials|many monuments to commemorate the dead]]. Larger cemeteries have a [[Stone of Remembrance]], designed by him.<ref>[http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0009128 Canadian Encyclopedia Monuments, World Wars I and II] {{wayback|url=http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0009128 |date=20110810000000 |df=y }}</ref> The best known of these monuments are the [[The Cenotaph, Whitehall|Cenotaph]] in [[Whitehall]], [[Westminster]], and the [[Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme|Memorial to the Missing of the Somme]], [[Thiepval]]. The Cenotaph was originally commissioned by [[David Lloyd George]] as a temporary structure to be the centrepiece of the Allied Victory Parade in 1919. Lloyd George proposed a [[catafalque]], a low empty platform, but it was Lutyens' idea for the taller monument. The design took less than six hours to complete. Many local war memorials such as the one at [[All Saints' Church, Northampton|All Saints', Northampton]], [[Montréal]], Toronto, [[Hamilton, Ontario|Hamilton (Ontario)]], [[Victoria, British Columbia|Victoria (British Columbia)]], and [[Vancouver]] are Lutyens designs, based on the Cenotaph. So is the war memorial in Hyde Park, Sydney. He also designed the [[National War Memorial, Islandbridge|War Memorial Gardens]] in Dublin, which were restored in the 1990s. Other works include the [[Tower Hill memorial]], and (similar to his later [[India Gate]] design) the [[Arch of Remembrance]] memorial in [[Victoria Park, Leicester]]. |

||

Lutyens also refurbished [[Lindisfarne Castle]] for its wealthy owner. |

Lutyens also refurbished [[Lindisfarne Castle]] for its wealthy owner. |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

Built in the spirit of British colonial rule, the place where the new imperial city and the older native settlement met was intended to be a market; it was there that Lutyens imagined the Indian traders would participate in "the grand shopping centre for the residents of Shahjahanabad and New Delhi", thus giving rise to the D-shaped market seen today. |

Built in the spirit of British colonial rule, the place where the new imperial city and the older native settlement met was intended to be a market; it was there that Lutyens imagined the Indian traders would participate in "the grand shopping centre for the residents of Shahjahanabad and New Delhi", thus giving rise to the D-shaped market seen today. |

||

Many of the garden-ringed villas in the [[Lutyens' Bungalow Zone]] (LBZ)—also known as [[Lutyens' Delhi]]—that were part of Lutyens' original scheme for New Delhi are under threat due to the constant pressure for development in Delhi. The LBZ was placed on the 2002 [[World Monuments Fund]] Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites. It should be noted that none of the bungalows in the LBZ were designed by Lutyens—he only designed the four bungalows in the Presidential Estate surrounding Rashtrapati Bhavan at Willingdon Crescent now known as Mother Teresa Crescent.<ref>{{cite news |

Many of the garden-ringed villas in the [[Lutyens' Bungalow Zone]] (LBZ)—also known as [[Lutyens' Delhi]]—that were part of Lutyens' original scheme for New Delhi are under threat due to the constant pressure for development in Delhi. The LBZ was placed on the 2002 [[World Monuments Fund]] Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites. It should be noted that none of the bungalows in the LBZ were designed by Lutyens—he only designed the four bungalows in the Presidential Estate surrounding Rashtrapati Bhavan at Willingdon Crescent now known as Mother Teresa Crescent.<ref>{{cite news|title=Lutyens himself designed only four bungalows |url=http://www.hindustantimes.com/News-Feed/newdelhi/Lutyens-himself-designed-only-four-bungalows/Article1-707697.aspx |publisher=[[Hindustan Times]] |date=9 June 2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121022220818/http://www.hindustantimes.com/News-Feed/newdelhi/Lutyens-himself-designed-only-four-bungalows/Article1-707697.aspx |archivedate=22 October 2012 |df=dmy }}</ref> |

||

Other buildings in Delhi that Lutyens designed include [[Baroda House]], [[Bikaner House]], [[Hyderabad House]], and [[Patiala House Courts Complex|Patiala House]].<ref>Prakash, Om (2005). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=nzpYb5UOeiwC Cultural History Of India]''. New Age International, New Delhi. ISBN 81-224-1587-3. p. 217.</ref> |

Other buildings in Delhi that Lutyens designed include [[Baroda House]], [[Bikaner House]], [[Hyderabad House]], and [[Patiala House Courts Complex|Patiala House]].<ref>Prakash, Om (2005). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=nzpYb5UOeiwC Cultural History Of India]''. New Age International, New Delhi. ISBN 81-224-1587-3. p. 217.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:26, 21 December 2016

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 March 1869 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 1 January 1944 (aged 74) London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Royal College of Art |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | |

| Projects | New Delhi |

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, OM KCIE RA FRIBA (/ˈlʌtjənz/; LUT-yənz; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was a British architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memorials and public buildings. He has been referred to as "the greatest British architect of the twentieth (or of any other) century."[1]

Lutyens played an instrumental role in designing and building New Delhi, which would later on serve as the seat of the Government of India.[2] In recognition of his contribution, New Delhi is also known as "Lutyens' Delhi". In collaboration with Sir Herbert Baker, he was also the main architect of several monuments in New Delhi such as the India Gate; he also designed Viceroy's House, which is now known as the Rashtrapati Bhavan.[3][4]

Early life

He was born in London and grew up in Thursley, Surrey. He was named after a friend of his father, the painter and sculptor Edwin Henry Landseer. For many years he worked from offices at 29 Bloomsbury Square, London. Lutyens studied architecture at South Kensington School of Art, London from 1885 to 1887. After college he joined the Ernest George and Harold Peto architectural practice. It was here that he first met Sir Herbert Baker.

Private practice

He began his own practice in 1888, his first commission being a private house at Crooksbury, Farnham, Surrey. During this work, he met the garden designer and horticulturalist Gertrude Jekyll. In 1896 he began work on a house for Jekyll at Munstead Wood near Godalming, Surrey. It was the beginning of a professional partnership that would define the look of many Lutyens country houses.

The "Lutyens-Jekyll" garden overflowed with hardy shrubbery and herbaceous plantings within a firm classicising architecture of stairs and balustraded terraces. This combined style, of the formal with the informal, exemplified by brick paths, softened by billowing herbaceous borders, full of lilies, lupins, delphiniums and lavender, was in direct contrast to the very formal bedding schemes favoured by the previous generation in the 19th century. This new "natural" style was to define the "English garden" until modern times.

Lutyens' fame grew largely through the popularity of the new lifestyle magazine Country Life created by Edward Hudson, which featured many of his house designs. Hudson was a great admirer of Lutyens' style and commissioned Lutyens for a number of projects, including Lindisfarne Castle and the Country Life headquarters building in London, at 8 Tavistock Street. One of his assistants in the 1890s was Maxwell Ayrton.[5]

Works

Initially, his designs were all Arts and Crafts style, good examples being Overstrand Hall Norfolk and Le Bois des Moutiers (1898) in France, but during the early 1900s his work became more classical in style. His commissions were of a varied nature from private houses to two churches for the new Hampstead Garden Suburb in London to Julius Drewe's Castle Drogo near Drewsteignton in Devon and on to his contributions to India's new imperial capital, New Delhi, (where he worked as chief architect with Herbert Baker and others). Here he added elements of local architectural styles to his classicism, and based his urbanisation scheme on Mughal water gardens. He also designed the Hyderabad House for the last Nizam of Hyderabad, as his Delhi palace.

He also designed a chalk building, Marshcourt, in Hampshire, England. Built between 1901 and 1905, it is the last of his Tudor designs. In 1903 the main school building of Amesbury Prep School in Hindhead, Surrey, was designed and built as a private residence.[6] It is now a Grade 2* listed building of National Significance.

He also designed a columbarium – the Hannen Columbarium – for the Hannen family in Wargrave in 1905.

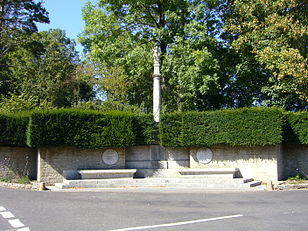

Before the end of World War I, he was appointed one of three principal architects for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now Commonwealth War Graves Commission) and was involved with the creation of many monuments to commemorate the dead. Larger cemeteries have a Stone of Remembrance, designed by him.[7] The best known of these monuments are the Cenotaph in Whitehall, Westminster, and the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, Thiepval. The Cenotaph was originally commissioned by David Lloyd George as a temporary structure to be the centrepiece of the Allied Victory Parade in 1919. Lloyd George proposed a catafalque, a low empty platform, but it was Lutyens' idea for the taller monument. The design took less than six hours to complete. Many local war memorials such as the one at All Saints', Northampton, Montréal, Toronto, Hamilton (Ontario), Victoria (British Columbia), and Vancouver are Lutyens designs, based on the Cenotaph. So is the war memorial in Hyde Park, Sydney. He also designed the War Memorial Gardens in Dublin, which were restored in the 1990s. Other works include the Tower Hill memorial, and (similar to his later India Gate design) the Arch of Remembrance memorial in Victoria Park, Leicester.

Lutyens also refurbished Lindisfarne Castle for its wealthy owner.

He was knighted in 1918[8] and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy in 1921.[9] In 1924, he was appointed a member of the newly created Royal Fine Art Commission,[10] a position he held until his death.

While work continued in New Delhi, Lutyens continued to receive other commissions including several commercial buildings in London and the British Embassy in Washington, DC.

In 1924 he completed the supervision of the construction of what is perhaps his most popular design: Queen Mary's Dolls' House. This four-storey Palladian villa was built in 1/12 scale and is now a permanent exhibit in the public area of Windsor Castle. It was not conceived or built as a plaything for children; its goal was to exhibit the finest British craftsmanship of the period.

Lutyens was commissioned in 1929 to design a new Roman Catholic cathedral in Liverpool. He planned a vast building of brick and granite, topped with towers and a 510-foot dome, with commissioned sculpture work by Charles Sargeant Jagger and W. C. H. King. Work on this magnificent building started in 1933, but was halted during the Second World War. After the war, the project ended due to a shortage of funding, with only the crypt completed. A model of Lutyens' unrealised building was given to and restored by the Walker Art Gallery in 1975 and is now on display in the Museum of Liverpool.[11] The architect of the present Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, which was built over land adjacent to the crypt and consecrated in 1967, was Sir Frederick Gibberd.

In 1945, a year after his death, A Plan for the City & County of Kingston upon Hull was published. Lutyens worked on the plan with Sir Patrick Abercrombie and they are credited as its co-authors. Abercrombie's introduction in the plan makes special reference to Lutyens' contribution. The plan was, however, rejected by the City Council of Hull.

He received the AIA Gold Medal in 1925.

In November 2015 the British government announced that all 44 of Lutyens' First World War memorials in England had now been listed on the advice of Historic England, and were therefore all protected by law. This involved the one remaining memorial—the Gerrards Cross Memorial Building in Buckinghamshire—being added to the list, plus a further fourteen having their statuses upgraded.[12][13]

Furniture

Lutyens has also designed furniture. He best-known furniture design is probably a garden bench; benches based on this design are still widely available.[14][unreliable source?]

New Delhi

Largely designed by Lutyens over twenty or so years (1912 to 1930), New Delhi, situated within the metropolis of Delhi, popularly known as 'Lutyens' Delhi', was chosen to replace Calcutta as the seat of the British Indian government in 1912; the project was completed in 1929 and officially inaugurated in 1931. In undertaking this project, Lutyens invented his own new order of classical architecture, which has become known as the Delhi Order and was used by him for several designs in England, such as Campion Hall, Oxford. Unlike the more traditional British architects who came before him, he was both inspired by and incorporated various features from the local and traditional Indian architecture—something most clearly seen in the great drum-mounted Buddhist dome of Viceroy's House, now Rashtrapati Bhavan. This palatial building, containing 340 rooms, is built on an area of some 330 acres (1.3 km2) and incorporates a private garden also designed by Lutyens. The building was designed as the official residence of the Viceroy of India and is now the official residence of the President of India.

The Delhi Order columns at the front entrance of the palace have bells carved into them, which, it has been suggested, Lutyens had designed with the idea that as the bells were silent the British rule would never come to an end. At one time, more than 2,000 people were required to care for the building and serve the Viceroy's household.

The new city contains both the Parliament buildings and government offices (many designed by Herbert Baker) and was built distinctively of the local red sandstone using the traditional Mughal style.

When composing the plans for New Delhi, Lutyens planned for the new city to lie southwest of the walled city of Shahjahanbad. His plans for the city also laid out the street plan for New Delhi consisting of wide tree-lined avenues.

Built in the spirit of British colonial rule, the place where the new imperial city and the older native settlement met was intended to be a market; it was there that Lutyens imagined the Indian traders would participate in "the grand shopping centre for the residents of Shahjahanabad and New Delhi", thus giving rise to the D-shaped market seen today.

Many of the garden-ringed villas in the Lutyens' Bungalow Zone (LBZ)—also known as Lutyens' Delhi—that were part of Lutyens' original scheme for New Delhi are under threat due to the constant pressure for development in Delhi. The LBZ was placed on the 2002 World Monuments Fund Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites. It should be noted that none of the bungalows in the LBZ were designed by Lutyens—he only designed the four bungalows in the Presidential Estate surrounding Rashtrapati Bhavan at Willingdon Crescent now known as Mother Teresa Crescent.[15] Other buildings in Delhi that Lutyens designed include Baroda House, Bikaner House, Hyderabad House, and Patiala House.[16]

Lutyens was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE) on 1 January 1930.[17]

A bust of Lutyens in the former Viceroy's House is the only statue of a Westerner left in its original position in New Delhi. Lutyens' work in New Delhi is the focus of Robert Grant Irving's book Indian Summer. In spite of his monumental work in India, Lutyens had views on the peoples of the Indian sub-continent that, although not uncommon for people of his class and his time, would now be considered racist.[18]

Ireland

Works in Ireland include the Irish National War Memorial Gardens in Islandbridge in Dublin, which consists of a bridge over the railway and a bridge over the River Liffey (unbuilt) and two tiered sunken gardens; Heywood Gardens, County Laois (open to the public), consisting of a hedge garden, lawns, tiered sunken garden and a belvedere; extensive changes and extensions to Lambay Castle, Lambay Island, near Dublin, consisting of a circular battlement enclosing the restored and extended castle and farm building complex, upgraded cottages and stores near the harbour, a real tennis court, a large guest house (The White House), a boathouse and a chapel; alterations and extensions to Howth Castle, County Dublin; the unbuilt Hugh Lane gallery straddling the River Liffey on the site of the Ha'penny Bridge and the unbuilt Hugh Lane Gallery on the west side of St Stephen's Green; and Costelloe Lodge at Casla (also known as Costelloe), County Galway (that was used for refuge by J. Bruce Ismay, the Chairman of the White Star Line, following the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic).

Lutyens is thought to have designed Tranarossan House, located just north of Downings on the Rosguill Peninsula on the north coast of County Donegal.[19]

Spain

In Madrid Lutyens' work can be seen in the interiors of the Liria Palace, a neoclassical building which was severely damaged during the Spanish Civil War.[20] The palace was originally built in the eighteenth century for James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick, and still belongs to his descendants. Lutyens' reconstruction was commissioned by Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart, 17th Duke of Alba. The Duke had met Lutyens while he was the Spanish ambassador to Great Britain.

Marriage and later life

Two years after she proposed to him and in the face of parental disapproval, Lutyens married Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964), third daughter of The 1st Earl of Lytton, a former Viceroy of India, and Edith (née) Villiers, on 4 August 1897 at Knebworth, Hertfordshire. They had five children, but the union was largely unsatisfactory, practically from the start. The Lutyens' marriage quickly deteriorated, with Lady Emily becoming interested in theosophy, Eastern religions and a fascination – emotional and philosophical – with Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Children

- Barbara Lutyens (1898–1981), second wife of Euan Wallace (1892–1941), Minister of Transport.

- Robert Lutyens (1901–1971), architect and interior designer. Designed the façade used for over forty Marks & Spencer stores.[21]

- Ursula Lutyens (1904–1967), wife of the 3rd Viscount Ridley. They were the parents of the 4th Viscount Ridley (1925–2012), and of Nicholas Ridley, Baron Ridley of Liddesdale (1929–1993), cabinet minister. Nicholas Ridley was the father of Edwin Lutyens' biographer, Jane Ridley.

- (Agnes) Elisabeth Lutyens (1906–1983), a well-known composer. Second marriage to the conductor Edward Clark.[22]

- (Edith Penelope) Mary Lutyens (1908–1999),[23] a writer known for her books about Jiddu Krishnamurti.

During the later years of his life, Lutyens suffered with several bouts of pneumonia. In the early 1940s he was diagnosed with cancer. He died on 1 January 1944 and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium where he had designed the Philipson Mausoleum in 1914–1916. His memorial, designed by his friend and fellow architect William Curtis Green, is in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral, London.

Major buildings and projects

- 1901: Deanery Garden, Sonning, Berkshire

- 1911: British Medical Association, Tavistock Square, London[24]

- 1928: Hyderabad House, New Delhi

- 1929: Rashtrapathi Bhavan, New Delhi

- 1930: Castle Drogo, Drewsteignton, Devon

- 1935: The Midland Bank, Manchester

- 1936: Baroda House, New Delhi

Gallery

-

Abbey House, Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria (1941)

-

Anglo-Boer War Memorial, Johannesburg (1910)

-

Britannic House, Finsbury Circus, London (1921–1925)

-

Campion Hall, Oxford (1936)

-

Castle Drogo, Devon (1911–1930)

-

Country Life Offices, Tavistock Street, London (1905)[25]

-

Free Church, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London (1908–10)

-

Daneshill Brick and Tile Company offices, near Old Basing, Hampshire (1903)[26]

-

Hampton Court Bridge, London (1933)

-

Hestercombe Gardens, Somerset, with Gertrude Jekyll (1904–1906)

-

The India Gate, New Delhi (1921)

-

Midland Bank Headquarters, Poultry, London (1924)[27]

-

67-68 Pall Mall, London (1928)[28]

-

Runnymede Bridge, Surrey (opened 1961)[29]

-

St Jude's Church, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London (1909–1935)

-

Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, France (1928–1932)

-

Tower Hill Memorial, Trinity Square, London (1928)

-

War Memorial, Mells, Somerset (1921)

-

Arch of Remembrance, Leicester (1925)

-

Architectural model of unrealised design for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (1933)[31]

-

Portico of the British School at Rome, (1916)

See also

- Category:Works of Edwin Lutyens (category)

- Landscape design history (category)

- History of gardening

- Herbert Tudor Buckland, a contemporary Arts & Crafts architect

- Butterfly plan

Notes

- ^ Stamp 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (1992). Architecture, Power, and National Identity. Yale University Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780300049589.

- ^ Goodman, David C.; Chant, Colin (1999). European Cities & Technology: Industrial to Post-industrial City. Routledge. ISBN 9780415200790.

- ^ Pile, John F. (2005). A History of Interior Design. Laurence King Publishing. p. 320. ISBN 9781856694186.

- ^ Ormrod Maxwell Ayrton at scottisharchitects.org.uk, accessed 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Amesbury School". Exploring Surrey's Past. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Canadian Encyclopedia Monuments, World Wars I and II Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "No. 30607". The London Gazette. 2 April 1918.

- ^ Having previously been an Associate of the Academy.

- ^ "No. 32942". The London Gazette. 3 June 1924.

- ^ Conserving the Lutyens cathedral model, Liverpool museums. Liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Retrieved on 29 July 2013.

- ^ "National Collection of Lutyens' War Memorials Listed". Historic England. Historic England. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Evans, Sophie Jane (7 November 2015). "Protecting the monuments that remember the fallen: All 44 of Sir Edwin Lutyens' WWI war memorials are listed by the government". The Daily Mail Online. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Sir Edwin Lutyens – The Creator Of Lutyens Bench". Lutyens Bench. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Lutyens himself designed only four bungalows". Hindustan Times. 9 June 2011. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Prakash, Om (2005). Cultural History Of India. New Age International, New Delhi. ISBN 81-224-1587-3. p. 217.

- ^ "No. 33566". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 1 January 1930. - ^ "The Architect And His Wife, The Life of Edwin Lutyens". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Alistair Rowan, The Buildings of Ireland: North West Ulster, P. 169. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2003 (originally published by Penguin, London, 1979).

- ^ Lutyens and Spain. Gavin Stamp and Margaret Richardson. AA Files No. 3 (January 1983), pp. 51–59 Architectural Association School of Architecture

- ^ "Robert Lutyens". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Clark, (Thomas) Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40709. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "(Edith Penelope) Mary Lutyens (1909–1999)". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b "About BMA House". BMA House. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Country Life building, Tavistock Street, London". RIBA. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Wright, Tony (February 2002). "Sir Edwin Lutyens and the Daneshill Brickworks". British Brick Society Information. 87: 22–26. ISSN 0960-7870.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064598)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "To Plan a Tour of Lutyens Buildings". The Luytens Trust. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Baldwin, Peter, ed. (2004). The motorway achievement. London: Telford. p. 308. ISBN 9780727731968.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1189781)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "Conserving the Lutyens cathedral model". Liverpool Museums. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

Sources

- Stamp, Gavin (2006). The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (2007 ed.). London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-896-7.

Publications

- Edwin Lutyens & Charles Bressey, The Highway Development Survey, Ministry of Transport, 1937

- Edwin Lutyens & Patrick Abercrombie, A Plan for the City & County of Kingston upon Hull, Brown (London & Hull), 1945.

Further reading

- Brown, Jane (1996). Lutyens and the Edwardians. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hopkins, Andrew; Stamp, Gavin (eds.) (2002). Lutyens Abroad: the Work of Sir Edwin Lutyens Outside the British Isles. London: British School at Rome. ISBN 0-904152-37-5.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Hussey, Christopher (1950). The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lutyens, Mary (1991). Edwin Lutyens. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Petter, Hugh (1992). Lutyens in Italy: the Building of the British School at Rome. London: British School at Rome. ISBN 0-904152-21-9.

- Ridley, Jane (2002). The Architect and his Wife.

- Skelton, Tim; Gliddon, Gerald (2008). Lutyens and the Great War. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2878-8.

External links

- The Lutyens Trust

- Jane Ridley, "Architect for the metropolis", City Journal, Spring 1998

- The creations of Sir Edwin Lutyens @ Ward's Book of Days

- The cathedral that never was – exhibition of Lutyens' cathedral model at the Walker Art Gallery

- Louvet, Solange; de Givry, Jacques. "The history of the Bois des Moutiers". – An 1898 house in France designed by Lutyens and its garden designed by Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll.

- Collection of over 2000 photo's of Lutyens' work on Flickr

- 1869 births

- 1944 deaths

- Artists from London

- People of the Victorian era

- British architects

- Neoclassical architects

- Arts and Crafts Movement artists

- Arts and Crafts architects

- Fellows of the Royal Institute of British Architects

- Royal Academicians

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Knights Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire

- Knights Bachelor

- Alumni of the Royal College of Art

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Golders Green Crematorium

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

![British Medical Association, Tavistock Square, London (1911)[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/BMA_House.JPG/308px-BMA_House.JPG)

![Country Life Offices, Tavistock Street, London (1905)[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Country_Life_Offices_London.jpg/265px-Country_Life_Offices_London.jpg)

![Daneshill Brick and Tile Company offices, near Old Basing, Hampshire (1903)[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Lutoffice8Jl6-3786.jpg/348px-Lutoffice8Jl6-3786.jpg)

![Midland Bank Headquarters, Poultry, London (1924)[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Lutyens_Midland_Bank.JPG/345px-Lutyens_Midland_Bank.JPG)

![67-68 Pall Mall, London (1928)[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/67-68_Pall_Mall.jpg/251px-67-68_Pall_Mall.jpg)

![Runnymede Bridge, Surrey (opened 1961)[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Runnymede_Bridge_%28upstream%29.JPG/371px-Runnymede_Bridge_%28upstream%29.JPG)

![Broughton memorial lodge, Runnymede, Surrey (1930–1932)[30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/LodgeRunnymede.jpg/347px-LodgeRunnymede.jpg)

![Architectural model of unrealised design for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (1933)[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/LPoolLutyens-wyrdlight-802726.jpg/308px-LPoolLutyens-wyrdlight-802726.jpg)