De-Stalinization: Difference between revisions

m Changed the first sentence, added more information pertaining to the events on 25 February 1956. |

HelgaStick (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Contemporary historians regard the beginning of de-Stalinization as a significant turning point in the [[history of the Soviet Union]]. It began during the [[Khrushchev Thaw]]. However, it subsided during the [[History of the Soviet Union (1964–82)|Brezhnev period]] and remained so until the mid-1980s, when it accelerated once again due to policies of ''[[perestroika]]'' and ''[[glasnost]]'' under [[Mikhail Gorbachev]]. |

Contemporary historians regard the beginning of de-Stalinization as a significant turning point in the [[history of the Soviet Union]]. It began during the [[Khrushchev Thaw]]. However, it subsided during the [[History of the Soviet Union (1964–82)|Brezhnev period]] and remained so until the mid-1980s, when it accelerated once again due to policies of ''[[perestroika]]'' and ''[[glasnost]]'' under [[Mikhail Gorbachev]]. |

||

==Beginnings |

==Beginnings== |

||

The term "de-Stalinization" is a term which gained currency following the [[collapse of the Soviet Union]], and was never used during the [[Khrushchev era]]. However, de-Stalinization efforts were set forth at this time by [[Nikita Khrushchev]] and the [[Government of the Soviet Union]] under the guise of the "overcoming/exposure of the cult of personality", with a heavy criticism of the [[Josef Stalin]]'s "era of the cult of personality".<ref name="Jones2006">{{cite book|author=Polly Jones|title=The Dilemmas of De-Stalinization: Negotiating Cultural and Social Change in the Khrushchev Era|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g7dYiQYo1nwC&pg=PA2|date=7 April 2006|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-28347-7|pages=2–4}}</ref> However, prior to [[On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences|Khrushchev's "Secret Speech"]] to the [[20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union|20th Party Congress]], no direct association between Stalin as a person and "the cult of personality" was openly made by Khrushchev or others within the party, although archival documents show that strong criticism of Stalin and [[Stalinism|his ideology]] featured in private discussions by Khruschchev at the [[Presidium of the Supreme Soviet]].<ref name="Jones2006" /> |

|||

==Khrushchev's "Secret Speech"== |

|||

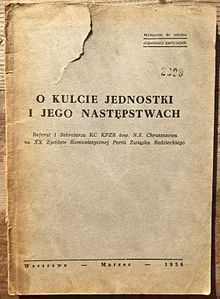

[[File:First edition of Krushchev's "Secret Speech".jpg|thumb|''O kulcie jednostki i jego następstwach'', Warsaw, March 1956, first edition of the Secret Speech, published for the inner use in the [[PUWP]].]] |

[[File:First edition of Krushchev's "Secret Speech".jpg|thumb|''O kulcie jednostki i jego następstwach'', Warsaw, March 1956, first edition of the Secret Speech, published for the inner use in the [[PUWP]].]] |

||

De-Stalinization meant an end to the role of large-scale [[labor camp|forced labour]] in the economy. The process of freeing [[Gulag]] prisoners was started by [[Lavrentiy Beria]]. He was soon removed from power |

De-Stalinization meant an end to the role of large-scale [[labor camp|forced labour]] in the economy. The process of freeing [[Gulag]] prisoners was started by [[Lavrentiy Beria]]. He was soon removed from power |

||

(arrested on June 26, 1953; executed on December 24, 1953) and [[Nikita Khrushchev]] then emerged as the most powerful Soviet politician.<ref>[http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1954succession&Year=1954 soviethistory.org]</ref> |

(arrested on June 26, 1953; executed on December 24, 1953) and [[Nikita Khrushchev]] then emerged as the most powerful Soviet politician.<ref>[http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1954succession&Year=1954 soviethistory.org]</ref> |

||

While De-Stalinization was quietly underway ever since Stalin's death, the watershed event was Khrushchev's speech entitled "[[On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences]]", concerning Stalin. On 25 February 1956, he spoke to a closed session of the [[20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union| |

While De-Stalinization was quietly underway ever since Stalin's death, the watershed event was Khrushchev's speech entitled "[[On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences]]", concerning Stalin. On 25 February 1956, he spoke to a closed session of the [[20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union|20th Party Congress]] of the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union]], delivering an address laying out some of Stalin's crimes and the "conditions of insecurity, fear, and even desperation" created by Stalin.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/907585907|title=The world transformed : 1945 to the present|last=H.|first=Hunt, Michael|publisher=|year=|isbn=9780199371020|location=|pages=153|oclc=907585907}}</ref> Khrushchev thoroughly shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's dictatorial rule and his [[cult of personality]] as inconsistent with communist and Party ideology. Among other points, he condemned the treatment of the [[Old Bolshevik]]s, people who had supported communism before the revolution, many of whom Stalin had executed as traitors. Khrushchev also attacked the crimes committed by associates of Beria. |

||

==Improved prison conditions== |

==Improved prison conditions== |

||

Revision as of 23:48, 9 March 2017

De-Stalinization (Russian: десталинизация, Destalinizatsiya) consisted of a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the ascension of Nikita Khrushchev to power.[1] The reforms consisted of changing or removing key institutions that helped Stalin hold power: the cult of personality that surrounded him, the Stalinist political system, and the Gulag labour-camp system, all of which had been created and dominated by him. Stalin was succeeded by a collective leadership after his death in March 1953, consisting of Georgi Malenkov, Premier of the Soviet Union; Lavrentiy Beria, head of the Ministry of the Interior; and Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

Contemporary historians regard the beginning of de-Stalinization as a significant turning point in the history of the Soviet Union. It began during the Khrushchev Thaw. However, it subsided during the Brezhnev period and remained so until the mid-1980s, when it accelerated once again due to policies of perestroika and glasnost under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Beginnings

The term "de-Stalinization" is a term which gained currency following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and was never used during the Khrushchev era. However, de-Stalinization efforts were set forth at this time by Nikita Khrushchev and the Government of the Soviet Union under the guise of the "overcoming/exposure of the cult of personality", with a heavy criticism of the Josef Stalin's "era of the cult of personality".[2] However, prior to Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" to the 20th Party Congress, no direct association between Stalin as a person and "the cult of personality" was openly made by Khrushchev or others within the party, although archival documents show that strong criticism of Stalin and his ideology featured in private discussions by Khruschchev at the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet.[2]

Khrushchev's "Secret Speech"

De-Stalinization meant an end to the role of large-scale forced labour in the economy. The process of freeing Gulag prisoners was started by Lavrentiy Beria. He was soon removed from power (arrested on June 26, 1953; executed on December 24, 1953) and Nikita Khrushchev then emerged as the most powerful Soviet politician.[3]

While De-Stalinization was quietly underway ever since Stalin's death, the watershed event was Khrushchev's speech entitled "On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences", concerning Stalin. On 25 February 1956, he spoke to a closed session of the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, delivering an address laying out some of Stalin's crimes and the "conditions of insecurity, fear, and even desperation" created by Stalin.[4] Khrushchev thoroughly shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's dictatorial rule and his cult of personality as inconsistent with communist and Party ideology. Among other points, he condemned the treatment of the Old Bolsheviks, people who had supported communism before the revolution, many of whom Stalin had executed as traitors. Khrushchev also attacked the crimes committed by associates of Beria.

Improved prison conditions

Khrushchev also attempted to make the Gulag labour system less harsh, by allowing prisoners to post letters home to their families, and by allowing family members to mail clothes to loved-ones in the camps, which was not allowed during Stalin's time.[5] Furthermore, when Stalin died, the Gulag was "radically reduced in size."[6] On October 25, 1956, a resolution of the CPSU declared that the existence of the Gulag labour system was "inexpedient".[7] The Gulag institution was closed by the MVD order No 020 of 25 January 1960.[8]

Re-naming of places and buildings

As part of the de-Stalinization push, Khrushchev endeavored to have many places bearing Stalin's name renamed or reverted to their former names, including cities, landmarks, and other facilities.[9] These included even capital cities of the Soviet republics and territories: in 1961, Stalinabad, capital of the Tajikistan, was renamed Dushanbe; Staliniri, capital of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast, was renamed Tskhinvali; and Stalingrad, a major industrial center of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, was renamed Volgograd.[10][11] In Ukraine, the Stalino Oblast and its capital, also named Stalino, were renamed Donetsk Oblast and Donetsk.

In a symbolic gesture, the State Anthem of the Soviet Union was purged of references to Stalin. The Stalin-centric and World War II-era lines in the lyrics were effectively excised when an instrumental version replaced it.

The Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, Poland was renamed in 1956.

Destruction of monuments

The Yerevan monument was removed in spring 1962 and replaced by Mother Armenia in 1967. Thousands of Stalin monuments have been destroyed not only in the Soviet Union but in Socialist countries. In November 1961 the large Stalin Statue on Berlin's monumental Stalinallee (promptly renamed Karl-Marx-Allee) was removed in a clandestine operation. The Monument in Budapest was destroyed in October 1956. The biggest one, the Prague monument, was taken down in November 1962.

Re-location of Stalin's body

Given momentum by these public renamings, the process of de-Stalinization peaked in 1961 during the 22nd Congress of the CPSU. Two climactic acts of de-Stalinization marked the meetings: first, on October 31, 1961, Stalin's body was moved from Lenin's Mausoleum in Red Square to a location near the Kremlin wall;[12] second, on November 11, 1961, the "hero city" Stalingrad was renamed Volgograd.[13]

See also

- Anti-Stalinist left

- History of the Soviet Union (1953–1964): De-Stalinization and the Khrushchev era

- Kureika (village)

- Khrushchev Thaw

- List of places named after Joseph Stalin

- Rehabilitation (Soviet)

- Denazification

- Decommunization

References

- ^ H., Hunt, Michael. The world transformed : 1945 to the present. p. 153. ISBN 9780199371020. OCLC 907585907.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Polly Jones (7 April 2006). The Dilemmas of De-Stalinization: Negotiating Cultural and Social Change in the Khrushchev Era. Routledge. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-134-28347-7.

- ^ soviethistory.org

- ^ H., Hunt, Michael. The world transformed : 1945 to the present. p. 153. ISBN 9780199371020. OCLC 907585907.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gulag : Soviet Prison Camps and their Legacy" (PDF). Gulaghistory.org. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ^ "Gulag: Soviet Forced Labor Camps and the Struggle for Freedom". Gulaghistory.org. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ^ Memorial http://www.memo.ru/history/nkvd/gulag/Articles/chapter3main.htm

- ^ Memorial http://www.memo.ru/history/NKVD/GULAG/r1/r1-4.htm

- ^ G.R.F. Bursa (1985). "Political Changes of Names of Soviet Towns". Slavonic and East European Review. 63.

- ^ Gwillim Law. "Regions of Tajikistan". Administrative Divisions of Countries ("Statoids"). Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Gwillim Law. "Regions of Georgia". Administrative Divisions of Countries ("Statoids"). Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ "CNN Interactive - Almanac - October 31". CNN.

(October 31) 1961, Russia's de-Stalinisation program reached a climax when his body was removed from the mausoleum in Red Square and re-buried.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Reuters (1961-11-11). "Stalingrad Name Changed". The New York Times.

MOSCOW, Saturday, Nov. 11 (Reuters) -- The "Hero City" of Stalingrad has been renamed Volgograd, the Soviet Communist party newspaper Pravda reported today.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)